By William Stroock

At 0100 hours on September 12, 1918, German positions in the St. Mihiel salient on the Western Front were lit up by a massive artillery barrage. In all, more than 3,000 Allied guns of all sizes and calibers bombarded the previously quiet position. To the Germans’ surprise, the barrage ceased after only four hours, and American troops on the north and south sides of the salient emerged from their positions and started the perilous trek across no-man’s-land. The Germans were stunned by the speed and ferocity of the assault. Their lines were lightly manned, while many of the defenses had been neglected. German units were caught hunkering down in their bunkers in preparation for an expected renewal of the artillery barrage.

Not since the Civil War had the U.S. Army assembled a mightier force. On the south side of the salient were two U.S. corps comprising seven divisions. On the north were an additional three divisions, one of them French. Seven American divisions remained in reserve. In all, more than half a million men supported by 267 tanks and 600 aircraft were gathered for the first grand American offensive of World War I. The American First Army was commanded by General John J. Pershing, a career soldier with much combat experience in Mexico and the Philippines.

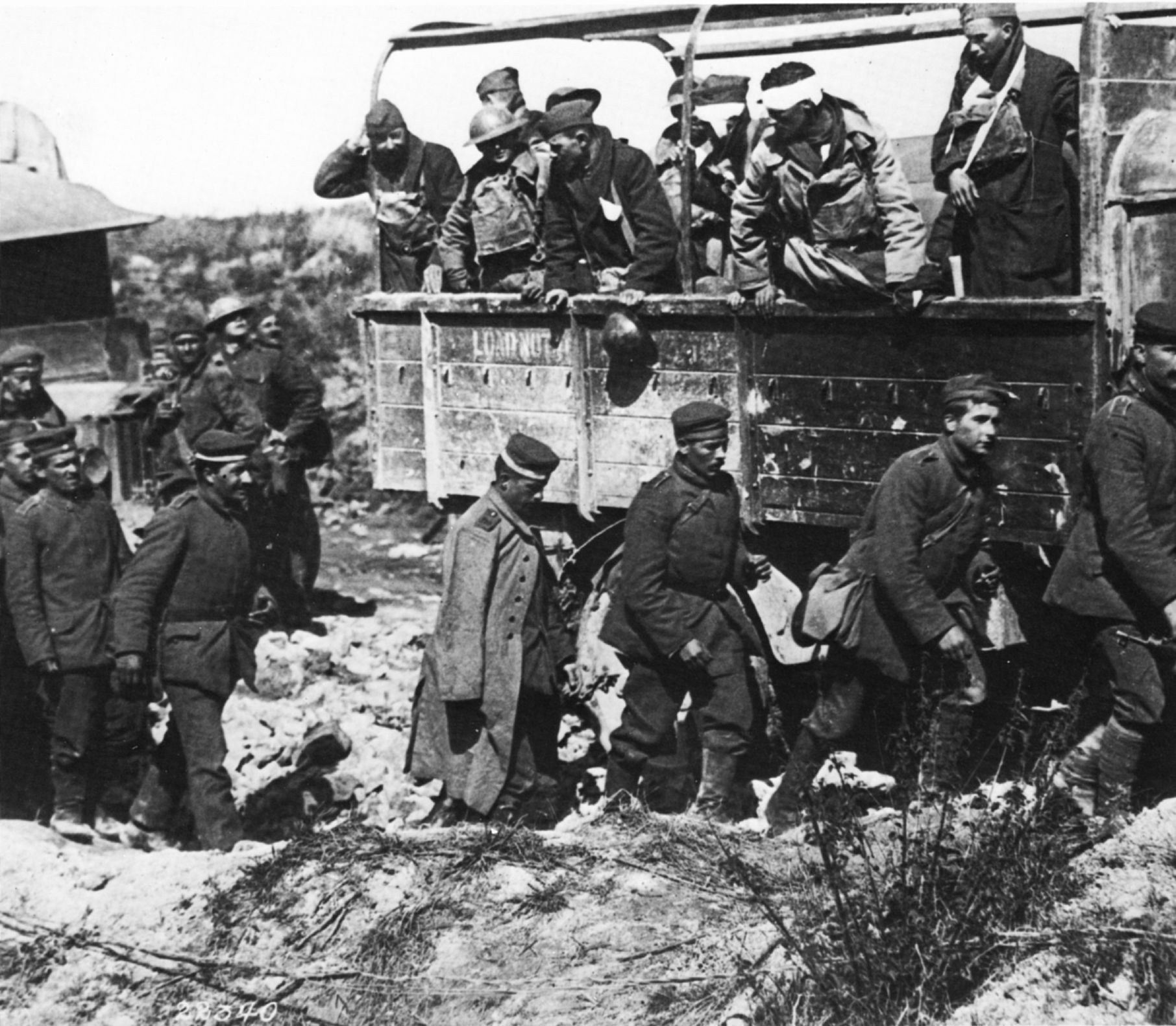

German and Austrian resistance crumbled before the onslaught. Within two days, American forces had cleared the salient, establishing a line less than 10 miles from Metz, the German-held city and crucial crossroads. The attackers seized more than 400 artillery pieces and 700 machine guns, along with 16,000 prisoners. The Americans suffered 7,000 casualties. In truth, the Yanks were lucky. Although well planned and executed, the assault was carried out against a phantom enemy. Knowing that the St. Mihiel salient was an easy target and sensing that American forces were massing in the south for some sort of offensive, General Erich Ludendorff, the German commander on the Western Front, had begun quietly withdrawing troops from the sector two days earlier.

French Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the supreme Allied commander, had tried unsuccessfully to prevent the St. Mihiel attack from happening in the first place. The day he turned over command of the sector to Pershing, Foch visited his headquarters and proposed that the attack be drastically scaled back and that American reserves be dispatched to the Aisne sector. This was the revival of an old scheme, advocated by the British as well as the French, in which American troops would be dispersed piecemeal among Allied forces. The Allies initially demanded that the Americans simply be used as replacements for battered British and French units.

Pershing strongly disagreed. “The further we proceeded in the discussion,” he recalled later, “the more apparent it became to me that the result of any of these proposals would be to prevent, or at least seriously delay the formation of an American army.” The two generals argued for some time. Foch pressed his demand to divide the American army. Finally, Pershing said, “Marshal Foch, you have no authority as Allied commander in chief to call upon me to yield up my command of the American army and have it scattered among Allied forces where it will not be an American army at all.” “I must insist,” Foch said. Pershing replied, “Marshal Foch, you may insist all you please, but I decline absolutely to agree to your plan.”

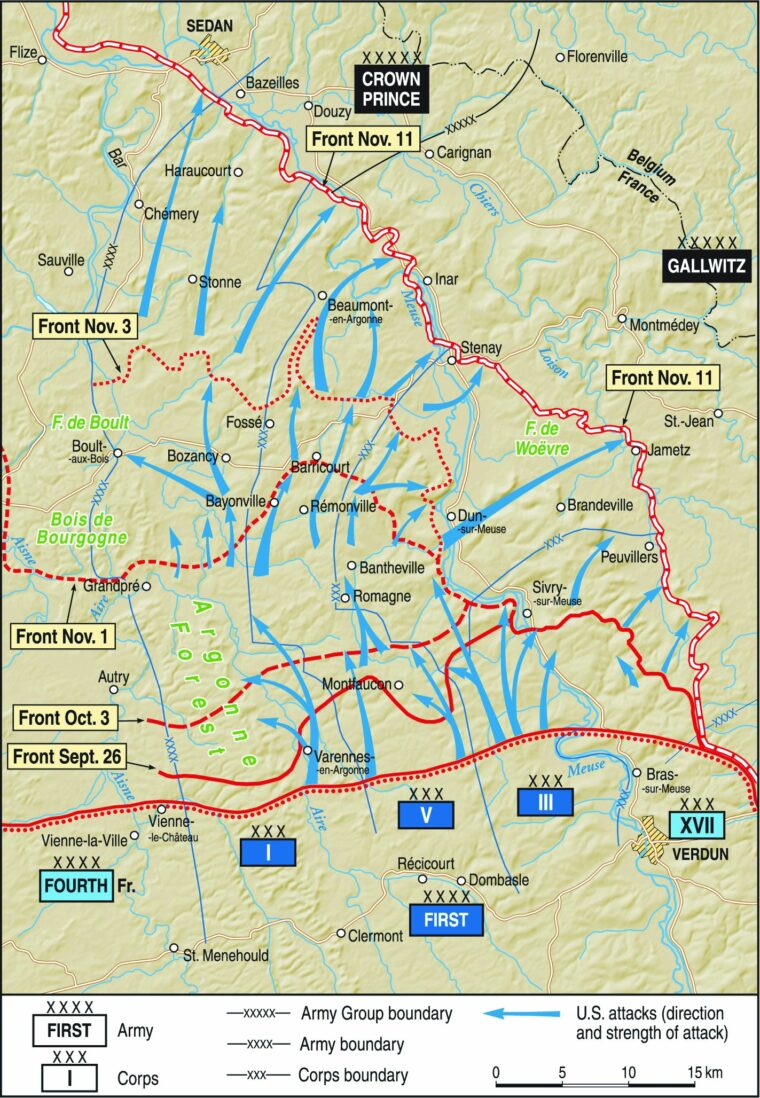

As the price for Foch’s reluctant acquiescence, Pershing had to give up his old idea of pushing toward Metz; instead, he shifted his forces for a grand attack in the Meuse-Argonne in conjunction with French and British forces. Pershing’s task was to advance 10 miles and link up with the French Army on his left at the town of Grandpre, at the northern tip of the Argonne. This would be followed by a second drive another 10 miles north to a line between the towns of Stenay and Le Chesne on the River Meuse. He was instructed to push German forces off the heights on the east bank of the Meuse. For that task he had three corps: I, II, and V. Guarding Pershing’s right was the French XVII Corps, positioned on the east bank of the Meuse.

Several factors would make this attack much rougher going than St. Mihiel. First, the Germans were waiting for a fight. The battle area was occupied by Army Group Von Gallwitz, part of the German Fifth Army. Overall, there were five divisions in line, with another 12 in reserve. Most of these formations were understrength, some by as much as a third. General Max Von Gallwitz was an experienced general who had seen action in Russia and at Verdun and the Somme. Second, the American First Army would be pushing north through the Aire Valley with the Argonne Forest on its left and the Meuse on its right. The terrain was dotted by woods not yet leveled by artillery and by several hills, all of which the Germans fortified. There were also three lines of defense, including the Kriemhilde Stellung, part of the Hindenburg Line of fortifications, running across the Romagne and Cunel Heights, just north of the main line, and the Freya Stellung, three miles farther north.

The heights on the east bank of the Meuse were also well defended. German positions there could deliver artillery and machine-gun fire into the American flank and would have to be neutralized. Third, the logistical situation was much more difficult, with the American sector being fed by three narrow and badly neglected roads. Lastly, because Pershing’s best divisions had been deployed at St. Mihiel, where they now rested and regrouped, the attack would have to be made by tens of thousands of only partially trained troops. Five divisions, the 35th, 37th, 79th, 80th, and 91st, were hurriedly pulled out of training areas and thrust into line.

In early September, Pershing set about the task of extracting the bulk of the First Army from St. Mihiel and marching north, a movement of hundreds of thousands of men, 15 divisions in all, over roads already clogged with French forces moving into the battle area. Each division was allotted time on the road and assigned specific spots to halt during the day. New rail lines were laid out as well. Massive supply depots would have to be established, filled, and secured near the front. Following these were replacement camps and hospitals. Three corps and one army headquarters would also have to be picked up, moved north, and reestablished. Worse still, Pershing insisted that the movements be conducted at night.

Owing to the success at St. Mihiel, Pershing, like the rest of the American Army, was overconfident. He hoped to achieve tactical surprise in the Meuse-Argonne and stressed the need to move rapidly before German reinforcements could be brought to the area. He believed that Montfaucon, a strongpoint in the center of the German line, and the Cote de Marie, a piece of high ground to the rear, must both be taken by the end of the second day. From there, he wanted a breakthrough where his open-warfare tactics of marksmanship and maneuver could be used more effectively. Pershing counted on breaking through the German front with simple blunt force and structured American divisions for the task. While Allied divisions were composed of three brigades, Pershing’s divisions were composed of four. Pershing believed that earlier British and French offensives had failed to break through because of a lack of resources. He felt that by packing his divisions with an extra brigade, they could better replace the losses suffered early in an attack.

The attack began at 0530 hours on September 26. By and large, the first day went well. Covered by an early-morning fog and accompanied by a rolling artillery barrage, most American units advanced to the German first line of defense against only minor enemy activity. The deepest penetration was made on the right flank by III Corps, led by the 33rd and 80th Divisions, which advanced almost five miles. Late in the day, as the Americans advanced past the first line of defense, German resistance perked up. Here, the Yanks encountered strongpoints, machine-gun nests, and sniper perches. Once the fog lifted, German artillery began to make itself felt on the battlefield. Exacerbating the Americans’ exposure was the lack of artillery support; many forward commanders were simply unable to keep up with their own rolling barrage. By the end of the first day’s fighting, the Germans had managed to stop the AEF’s advance well short of Pershing’s objectives. Casualties were heavy.

By far the unit that had suffered the most was the green 79th Division, part of V Corps, which launched a frontal assault on Malancourt. The village occupied a central spot in the German line and needed to be taken before an assault could begin on the German strongpoint at Montfaucon. German defenders in the village and on the American right in the Bois de Malancourt exacted a heavy toll as the 79th advanced. Once the fog lifted, artillery added to the carnage. The 79th fought its way into Malancourt and then pushed on to the main target, Montfaucon, where it encountered heavy resistance on the left from Germans atop Hill 282. Caught in a vicious crossfire, the 79th got bogged down. The Germans left Hill 282 only when the American 4th Division lapped around their flank and swung north of the hill.

Despite the roads being completely jammed, holding up supplies and artillery batteries that could not be hauled through the mud, Pershing pressed the attack. The Germans were now thoroughly alerted, with supplies and reinforcements streaming in. Hard fighting followed. Although V Corps was able to take Montfaucon on the second day, it suffered heavy casualties when it attacked German positions in the woods to the north, the Bois de Fey and Bois de Ogons.

All across the line, American progress was undone by ferocious German counterattacks. The 91st Division, operating on V Corps’ right, had the worst of it. The 91st fought a seesaw battle for the village of Epionville, a German strongpoint atop a small ridge in front of the division’s second line of defense. The Americans took Epionville on September 27 but were quickly forced out by a German counterattack on the division’s left flank. Having bloodied the Americans, the Germans pulled back from Epionville to their main defenses on the heights to the north.

By October 1, the end of the first phase of the attack, the AEF had advanced about eight miles. Casualties were staggering, overwhelming medical detachments in the rear. The 37th Division suffered 3,600 casualties, and the 91st suffered 4,700. All told, the AEF lost 26,000 dead and wounded in the first phase of the offensive. German artillery was the main culprit, accounting for nearly 75 percent of American losses.

Not satisfied with the pace of the attack, Pershing halted the operation, took stock, and reorganized. The performance of the five green divisions was sorely lacking. Inexperienced officers relied on foolish frontal assaults against entrenched, battle-tested Germans. Tanks were unable to keep up with the advance, and the artillery often failed to respond to fire-support requests. Many officers were sacked after the disaster at Montfaucon, including the V Corps commander, General George Cameron. Pershing assigned a pair of his veteran staff officers to help straighten things out in the 28th Division, whose commander complained of a lack of trained officers. Pershing withdrew the 37th and 79th Divisions and replaced them with the veteran 3rd and 32nd Divisions. The 35th Division was replaced by the mighty 1st Division. The 91st Division was pulled out of the line into reserve and not replaced.

Pershing resumed the attack on October 4. His objective was the Romagne Heights and the Cunel Heights, including the town of Cunel and the Bois de Cunel to its north. The highest point on the Romagne Heights was the Cote de Marie—taking it would make the remaining German positions on the heights untenable. III Corps advanced along a two-division front. The ensuing fight was a testament to the professionalism and tenacity of the German forces. The defenders stopped two assaults by the 4th Division, but a third broke through into the woods and the far side. The 4th continued north and hit the Bois de Peut de Faux, but was stopped cold. On the right, the 80th Division attacked the Bois de Ogons across a cratered field. The attack on the first day failed, but the 80th pushed on and eventually advanced to a point just southeast of Cunel before Pershing pulled the battered division out of line.

To the west, V Corps attacked along a two-division front as well. On the right, the 3rd Division made good progress until it reached the Bois de Cunel. Withering machine-gun and artillery fire stopped the advance. Undaunted, the division renewed the attack on the Bois de Cunel and fought its way into the wood; it was in American hands by the evening of October 10. On the left, the 32nd Division captured the village of Gesnes and then pushed on to the outskirts of the village of Romagne. The division ran into stiff resistance as it advanced farther north to the outskirts of Cote de Marie. A German counterattack drove the division out of town and off the hill, forcing the 32nd to dig in to the south. On the 32nd Division’s left, the 91st Division attacked the adjacent Hill 255 and took the position after severe fighting. The 91st advanced the next day against Hill 288 but was stopped by massed machine guns and accurate artillery fire.

On the First Army’s left, I Corps pushed into the Argonne. The 1st Division advanced east of the forest with the goal of breaking through the German line to the north and reaching the village of Sommerance behind the Germans’ line of communication. The Big Red One drove three miles in just one day, taking the German strongpoint atop Hill 272 on October 9 and the village of Cote de Maldah the next day. This move opened up space for an attack into the Argonne from the east, which was undertaken by the 82nd Division. Rain and German artillery caused the 82nd to get off to a slow start, but it managed to fight its way inside the forest to Hill 180, which it took against light German resistance.

A heavy German counterattack fell upon the 82nd the next day, preventing the division from exploiting its success. The 82nd attacked toward Hill 233, on the eastern edge of the forest, where it was repelled with heavy losses. The division made good progress the next two days, pivoting north and taking the village of Cornay, which then was lost to a German counterattack. The 82nd Division’s hard slogging put heavy pressure on the Germans still in the Argonne and forced them to pull back. The 77th Division pursued them to the forest’s northern edge.

Pershing paused once again. He toured his divisions and spoke with their commanders, explaining the need for American troops, once a position had been taken, to dig in and prepare to repel the inevitable German counterattack. By emphasizing such action, Pershing hoped to minimize the seesaw nature of the campaign, which had seen numerous positions taken and then lost because commanders were not prepared to meet German counterattacks.

The AEF had suffered heavily, losing nearly 75,000 men since September 26. A further drain was the worldwide influenza epidemic, which had already made 70,000 men sick. With manpower growing scarce, Pershing altered the basic rifle company structure, trimming it down from 250 to 175 men. Two divisions, the 84th and 86th, which had just disembarked, were cannibalized for replacements. During this time, Pershing split the AEF in two, forming the Second Army and placing General Robert Lee Bullard, then heading III Corps, in command. First Army went to General Hunter Liggett, commander of V Corps. Pershing now commanded a de facto army group.

On the west bank of the Meuse, Pershing resumed the attack on October 14, with the goal of finally taking Romagne and Cunel and clearing the entire heights. In the east, III Corps, led by the 3rd Division and the fresh 5th Division, attacked the Bois de Bantheville and Bois de Rappes. The 3rd Division took the former, but the 5th Division was unable to make any headway against the latter. To the east, V Corps, with the 32nd Division in the lead, attacked and finally took Romagne, then dashed north and took the Cote de Marie, perhaps the most important strongpoint on the Hindenburg Line.

On the left, the fresh 42nd Division descended the Romagne Heights and attacked the Cote de Chatillion, breaking German defenses there and continuing north. To the west, V Corps attacked in the area of Grandpre. After advancing more than a mile to the outskirts of the village of St. Juvan, east of Granpre, V Corps encountered stiff German resistance and was unable to go farther. On the left, the 77th Division moved up and attacked St. Juvin, taking it on October 14. The 77th continued north and fought into the southern section of Grandpre but was unable to take the town.

While the American First Army was slugging it out with the Germans, the French XVII Corps crossed the Meuse and attacked German positions atop the high ground on the east bank. The ground in question was a series of hills overlooking the river and the Argonne. On the east bank, from south to north, were the villages of Brabant, Consenvoye, Sivry, and Dun-sur-Meuse. In the center of the German line was Richene Hill. Taking it was the key to holding the east bank of the Meuse. On the extreme right of the XVII Corps area of operations was the village of Beaumont. Pershing hoped to drain German divisions from the fight and to expand his frontage, which would allow for greater maneuver and further dilute German defenses.

The French XVII Corps actually contained two American divisions, the 29th and 33rd, both still on the west bank of the Meuse, and it was these formations that spearheaded the drive. On the night of October 8, engineers of the 33rd Division erected several bridges across the Meuse with the goal of taking the Borne de Cornoulilier, a height overlooking the river north of the German main line. The doughboys crossed the bridges under heavy German fire and struck Broen and German positions around the village of Consenvoye, taking it and driving up the slopes to the north at the base of Richene Hill.

The Germans repulsed several assaults up the hill. To the south, the 29th Division crossed the Meuse and spent the next three days clearing Germans out of the woods around Richene Hill. XVII Corps was reinforced by the 10th Colonial Division and the American 26th Division. After pausing, XVII Corps renewed its offensive, attacking German positions at Molleville Farm, east of Richene Hill, which fell after a day’s fighting.

Now Pershing directed Bullard’s Second Army to continue the push up the east bank of the Meuse and attack the towns of Damvilliers and Dun-sur-Meuse. At the same time, Liggett was to hold the Germans in place, advance north, and pivot east to the Meuse. The Germans occupied a line beginning in the west at the Bois de Bourgonne and running east along Barricourt Ridge from Buzancy to the Meuse. I Corps was to clear the Bois de Bourgonne and effect a junction with the French Fourth Army, while III and V Corps would take Barricourt Ridge.

First Army’s attack was to begin on October 28, but after consulting with the French Fourth Army commander, who asked for a few more days to prepare, Liggett agreed to postpone the attack until November 1. The American attack got under way at 0530 hours and swept the Germans before them. On the center and right, III and V Corps stormed Barricourt Ridge, attaining all of their stated objectives by nightfall and advancing more than six miles. The doughboys encountered German fortifications smashed by now-accurate American artillery fire. Tellingly, Germans started giving up en masse.

Opposite what remained of the Kriemhilde Stellung, I Corps had more mixed results. Advancing on the right, the 80th Division made good progress and pushed through abandoned German positions. But on the left, the 78th Division was stopped without advancing even a mile. Concealed by the wood, the Germans contested every inch of ground. The 80th Division was forced to peel off and link up with the French Fourth Army near the town of Boult aux Bois. While Pershing was concerned about the movement, Liggett was not, stating simply that with V and III Corps driving north, the Germans in the Bois de Bourgonne would be compelled to withdraw.

The next day saw even better results. V Corps drove several miles up the bank of the Meuse, taking Villiers-devant-Dun and Stenay. The 5th Division tried to cross the Meuse in the vicinity of Sivry-dun-Meuse, but came under heavy machine-gun and artillery fire from the far bank. That night, under cover of rain and fog, engineers erected a small bridge to the south at Brieulles. In the morning, elements of the 5th Division crossed under heavy fire and drove north along the east bank, securing a damaged iron bridge. The bridge was repaired that night, and reinforcements crossed the river to join their comrades.

By the night of November 5, the division was firmly established on the east bank. III Corps pushed on and by evening had reached the outskirts of Beaumont, more than five miles north of its previous day’s position. The French XVII Corps linked up with III Corps and expanded the front of the attack to the east, taking Montmedy, which gave them a bridgehead across the Chiers River and the option of darting east against Metz. Because of their collapsing position to the east, German forces in the Bois de Bourgonne withdrew, just as Liggett said they would, ceding the ground to I Corps, which advanced another six miles. Liggett exulted, “The blow delivered by the 3rd and 5th Army Corps was so heavy and so completely successful that the enemy was unable to make any offensive return at all.”

From Barricourt, V Corps continued north and, over the next few days, advanced another six miles, taking Beaufort on November 4 and Villemontry, on the banks of the Meuse, on November 6. On the left, I Corps duplicated the feat. Advancing on a two-division front, with the 80th and 77th divisions in the lead, I Corps marched down the ridge and dashed across the ground below, rolling more than 10 miles over the next three days and occupying several points along the Meuse. The 77th Division effected a crossing of the Meuse at Villers on November 7.

With his long-sought-after breakthrough now achieved, Pershing was thinking of making a strategic breakthrough into the Rhine and Saar valleys. “I felt full advantage should be taken of the possibility of destroying the armies on our front and seizing the region upon which Germany largely depended for her supply of iron and coal,” he noted. Accordingly, Pershing issued orders emphasizing the need to advance “without regard for fixed objectives and without fear for their flanks.” He again emphasized boldness and open-warfare methods.

Pershing continued looking north and hoped to launch an attack on the city of Sedan, which was located just a few miles from the I Corps forward defenses. Pershing wanted the honor of entering Sedan to fall to the First American Army. Chaos ensued. The I Corps commander, General Charles Summerall, felt the order was open to interpretation and determined to make a dash for Sedan. A race developed between V and I Corps. While the 42nd Division was advancing on Sedan, the 1st Division (on Summerall’s orders) jumped the gun and advanced across the 42nd Division’s front and nearly got fired upon. An angry Liggett drove to V Corps headquarters and ordered the 1st Division to fall back.

Pershing was equally livid. “Under normal conditions the action of the officer or officers responsible for this movement of the 1st Division could not have been overlooked,” he wrote, “but the splendid record of that unit and the approach of the end of hostilities suggested leniency.” By November 11, both the 42nd and 1st Divisions were on the heights overlooking Sedan. But before the ultimate attack could be properly developed, the Germans agreed to a cease-fire.

During the last few days of the war, with the bulk of the First Army on the east bank of the Meuse and pressing east-northeast, the Second Army attacked as well. These were small-scale operations, meant to gain local advantage for possible exploitation later. The Second Army attacked along a four-division front and encountered heavy resistance, advancing less than a mile. On November 7, Marshal Foch requested that half a dozen American divisions be detached for a joint Franco-American offensive toward Chateau Saline, south of Metz. As Pershing had initially wanted to attack in this direction anyway, he was willing to provide the necessary troops. The attack would begin on November 14. Of course, it never happened. The war had ended three days earlier.

Pershing’s First and Second Armies had cleared the Meuse-Argonne sector and positioned themselves to take Sedan and Metz, moves that would have threatened Germany’s very ability to wage the war. In the course of operations, they shattered the German Fifth Army; inflicted 100,000 casualties; and captured 26,000 men, 974 guns, and 3,000 machine guns. The AEF, in turn, suffered 117,000 dead and wounded. In many ways, the greatest accomplishment was logistical. Pershing and his staff pulled the AEF out of one area, moved the army dozens of miles to north, and commenced an entirely new offensive within weeks.

Pershing’s own summation of the Meuse-Argonne campaign, and indeed the entire AEF, takes up only a few pages at the end of his two-volume, Pulitzer Prize-winning memoirs. Like Ulysses S. Grant’s post-Civil War memoirs, they are a literary achievement as well as a historical record. The immense pride Pershing felt in his officers and men shines through the last paragraphs. Humble to the end, Pershing points out that the AEF was not perfect: “The divisions with little training, while aggressive and courageous they were capable of powerful blows, but their blows were apt to be awkward and teamwork was often not well understood.” Despite his quibbles, the battles in the Meuse-Argonne should be better remembered than they are by Americans, taking a place alongside such other forest battles as the Wilderness and the Bulge in the nation’s other two great wars.

Need more details

My father was with the 28th Division as a combat engineer and built bridges under German artillery fire during 1917 and 1918.

My grandfather fought in this battle, infantryman, 4th ID. He was wounded in this battle. General Summerall was US Army Chief of Staff from Nov 1926 to Nov 1930, replaced by Douglas MacArthur.

This actually vindicated Pershing’s plan to ensure that his army was trained and capable before being assigned to a front line area. The British and French had wanted to send the Americans piece meal to fill in their own units that had been depleted with various unsuccessful operations in the previous three years. Pershing knew that more of the same was likely to continue the meat grinder operations that both sides had engaged in with only more casualties to show for it. His success soon quieted the criticism.

This article needs more detailed maps, and ignores some important episodes- as one who has led battlefield staff rides to the Meuse-Argonne battlefields, I find it hard to comprehend writing this with no mention of Patton’s actions, Harry Truman’s actions, the Lost Batallion, Sergeant York or Sam Woodfill. In all a very high level overview which is hard to follow at times, even for one who know the ground well, due to the lack of detailed maps.

Thanks for taking the time to leave a comment. As magazine publishers (and now web publishers) we are constrained by the length of our stories as they are presented in our publications. To provide the scope of material you mention requires a story of book length, and there are a number of good books on this subject. However, that’s not to say we have ignored some of the subjects you mention. For instance, you may care to check out these stories that we have published:

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/harry-truman-on-the-western-front/

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/patton-in-wwi/

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/sergeant-alvin-york-personal-accounts-that-reveal-his-true-story/