By Michael Williams

On March 14, 1988, a solemn ceremony took place at Arlington National Cemetery. Resplendent in their white caps and dress blues, the Marine body bearers laid to rest the ashes of Ernest Cuneo in the Columbarium with full military honors.

It took a special request to grant this honor because Cuneo had not become a Marine until com- missioned as a major in the reserves at the age of 53 and had never served a day on active duty. Nevertheless, the 16 distinguished members of “Ernie’s Gang,” former comrades from America’s intelligence, diplomatic, and military communities, were disappointed that their efforts had fallen short. They had hoped to secure the Presidential Medal of Freedom for their friend. As a man who kept to the shadows, Cuneo would likely have preferred the quiet dignity of the Marine internment.

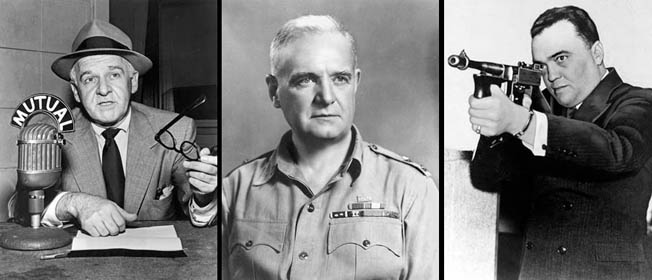

Weighing more than 200 pounds, former college and NFL lineman Ernest Cuneo was a hard man to overlook. The fact that history has done so is a tribute to how well he performed his duties. During World War II Cuneo served as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s liaison among British Intel- ligence, the FBI, and the OSS, the forerunner of today’s CIA. William Stephenson, head of British Security Coordination, and the man called “Intrepid,” conferred on Cuneo the code name “Crusader.”

Cuneo also performed a second secret role for FDR: shaping American public opinion by ghost- writing newspaper columns and radio broadcasts for Walter Winchell, the era’s most influential journalist. Cuneo also had close ties to Washington political columnist Drew Pearson. The brawniest of FDR’s brain trust, Cuneo served as conduit for the administration’s covert and overt wartime policies. A gregarious, Falstaffian character equally at home quoting the classics or cutting political deals, the one thing Cuneo never sought was public recognition. “I always liked to keep out of sight,” he wrote, “Anonymity is freedom.” Born in 1905 in Carlstadt, New Jersey, to Ital- ian immigrant parents, Cuneo graduated from East Rutherford High School and attended Penn State University to play football and study law. After being booted from the team for some infraction, he continued his studies at Columbia and earned All-American honors for his play at left guard.

During summers Cuneo earned money for school by writing stories for the New York Daily News. While completing his law degree, he played two seasons in the NFL for the Orange Tornadoes and the Brooklyn Dodgers. Then New York Congressman Fiorello LaGuardia hired Cuneo as an aide, and he continued to serve LaGuardia as a behind the scenes fixer after LaGuardia became mayor of New York City. In 1936, Party Chairman James Farley appointed Cuneo as associate general counsel to the Democratic National Committee. He helped Michigan Governor Frank Murphy mediate a historic agreement between General Motors and the United Auto Workers (UAW) to end the 1937 sit-down strike. Cuneo joined a group of liberal Democrats who met regularly at the Hotel Lafayette in New York City to strategize how to retain control of the party once Roosevelt, as expected, stepped down after two terms as president. Cuneo suggested that the only man who could provide instant recognition to a new candidate was Walter Winchell, a controversial journalist whose column was read by 50 million Americans and whose Sunday night radio broadcasts reached 20 million. When Tommy Corcoran objected that Winchell was “notches below the dignity of the White House,” Cuneo replied, “Necessity is above the gods themselves.” Cuneo met Winchell and became convinced that he possessed an intelligent and nimble mind but realized that he would have to feed Winchell’s insatiable appetite for scoops if he wanted Winchell to launch trial balloons for the upcoming presidential race.

Thus, a mutually beneficial relationship began. By 1940, Winchell was paying Cuneo $10,000 a year, officially for legal services, but Cuneo also supplied inside information and even ghostwrote portions of Winchell’s columns and broadcasts, particularly those dealing with national politics, defense, and international relations.

When FDR’s effort to purge anti-New Deal Democrats from Congress failed miserably in 1938, Cuneo and Corcoran concluded that the only way to save liberal Democrats in 1940 was for the president to run for an unprecedented third term. Cuneo enlisted Winchell as the mouthpiece of the “Draft Roosevelt” movement to flush out the opposition. “The enemy cannot be destroyed unless he is developed,” Cuneo explained. “We had nearly two full years to destroy it. We did.” FDR was grateful for the role Cuneo played in his reelection and invited him to share the presidential box for the inau- gural parade. Characteristically, Cuneo declined.

Winchell introduced Cuneo to another pow- erful Washington insider, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. The unlikely pair had been friends since 1934 when Hoover rewarded Winchell for his myth-making portrayals of Hoover and his intrepid G-men tirelessly hunting down gang- sters and spies by securing Winchell’s commis- sion as a lieutenant in Naval Intelligence.

Hoover and his deputy, Clyde Tolson, began joining Winchell for evenings at the Stork Club during their visits to New York City. Cuneo, Hoover, and Winchell all shared a deep belief in the power of secrets: discovering them, holding them, deciding when and how to disclose them.

Several of Cuneo’s most important Washing- ton links were forged during his student days at Columbia. Among his former professors were Adolf A. Berle and Drew Pearson. Berle, an expert on corporate law, had joined FDR’s unofficial brain trust during the 1932 election campaign and in 1938 was appointed Assistant Secretary of State for Latin America. Berle inherited the thankless job of coordinating the intelligence input—and refereeing the ongoing turf wars—of the FBI, the Office of Naval Intel- ligence (ONI), and the Army’s Military Intelli- gence Division (MID), as well as the State Department. Drew Pearson became a Washing- ton correspondent and in 1931 anonymously coauthored a book titled Washington Merry- Go-Round. It and a sequel were full of muck- raking exposés that led to a nationally syndi- cated column under the same title.

In 1940, the Roosevelt administration assigned Cuneo and Winchell a second task that overshadowed the third term debate: preparing the country for war. On March 24, Berle asked Cuneo to have Winchell “insert a stiff editorial on preparedness for the defense of the Hemi- sphere” into his Sunday night broadcast. Cuneo replied, “Adolf, the guy thinks he’s been doing it since 1930.” Later that night Cuneo phoned Berle to report that following the broadcast the lines had been jammed with favorable calls. However, these calls came from people who reg- ularly tuned in to hear Winchell, not a scientific cross-sample of Americans. Before Germany launched its blitzkrieg attacks on Western Europe many still hoped the United States could isolate itself from the conflict.

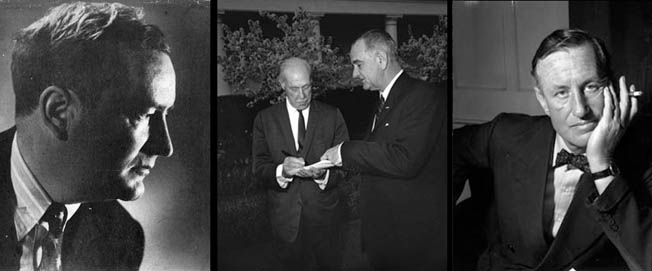

On April 2, 1940, a 44-year-old millionaire Canadian businessman named William Stephenson arrived in America on a mission for Britain’s Ministry of Supply. A mutual friend, boxer Gene Tunney, arranged a meeting between Stephenson and J. Edgar Hoover. Due to the State Department’s interpretation of America’s neutrality acts, official cooperation with British intelligence had been severed once Britain entered the war. Stephenson sought to reestablish those ties, but Hoover would only do so under two conditions: the president’s prior approval and that business be conducted personally through Hoover, excluding all other U.S. government agencies.

Following the Allied debacle in France and the Low Countries, Winston Churchill became prime minister of Great Britain on May 10, 1940. In early June, Churchill sent Stephenson to New York to assume command of British Passport Control, a front organization for MI- 6, the overseas arm of British intelligence. Fore- most among his many goals was to secure America’s aid and preferably its participation in the war against Hitler. Cuneo later observed, “Of course the British were trying to push the U.S. into war. If that be so, we were indeed a pushover.”

Hoover and Stephenson were empire builders, and the alliance they forged proved fruitful for both at first. On June 23, Hoover stepped closer toward his goal of becoming America’s sole intelligence czar when Roosevelt decreed that the FBI would assume responsibil- ity for intelligence operations throughout the Western Hemisphere. Stephenson moved the nerve center of British Passport Control to Suite 3603 in Rockefeller Center and swiftly expanded his network to employ over 2,000 operatives throughout North and South Amer- ica. Hoover suggested a name change to British Security Coordination (BSC). Over the next few years the BSC supplied the FBI with more than 100,000 reports, enabling Hoover’s men to nab dozens of Axis agents in the United States and Latin America. A key source for these reports was the BSC’s massive mail interception center in Bermuda, which steamed open thousands of trans-Atlantic missives.

By late August 1940, Cuneo was aware that the fix was in regarding the exchange of 50 U.S. destroyers for British naval bases. When his good friend Attorney General Robert Jackson asked Cuneo to come to his office one morning, Cuneo saw that “he was both sad and disturbed” that he would have to tell the president later that day “that the transfer of the 50 destroyers to Britain was unconstitutional. I told him not to feel too badly: that by one o’clock that day he would either reverse himself or be asked for his resignation.” As predicted, Jackson and the rest of FDR’s cabinet fell into line. Two weeks after that deal was announced, Roosevelt signed into law America’s first peacetime draft. These steps toward intervention were aided by the lack of opposition from Wendell Willkie, the Republi- can Party’s surprise nominee for president.

Cuneo saw Roosevelt’s reelection as a turning point. “Once having cleared the election barrier, FDR threw off the wraps, strapped on his hel- met and went in, went in, that is, as far as he could push American opinion to permit.”

Cuneo primed Walter Winchell’s “broad- sides” blasting isolationists, Nazi sympathizers, anti-Semites, and various other “Americans most Americans can do without” as Winchell labeled them in his weekly columns and Sunday night radio broadcasts, which combined to reach 90 percent of the American public. By November 1941, the U.S. had sent over a billion dollars in Lend-Lease materials to Britain, and American destroyers were engaging German U- boats as they helped convoy this aid. Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 helped end labor opposition to U.S. aid for Britain. “Before that,” Cuneo wrote, “there was tough going. The Communist-led unions were doing as much damage with strikes as a couple of U-boats in the Atlantic.”

America remained technically neutral as war raged on in 1941. “For the British,” wrote Cuneo, “it was a life or death struggle.” Cuneo had a front row seat as the BSC “ran espionage agents, tampered with the mails, tapped tele- phones, smuggled propaganda into the country, disrupted public gatherings, covertly subsidized newspapers, radios, and organizations, perpe- trated forgeries—even palming one off on the president of the United States (a map that out- lined Nazi plans to dominate Latin America)— violated the aliens registrations act, shanghaied sailors numerous times, and possibly murdered one or more persons in this country.”

It also helped create America’s first intelligence agency. William J. Donovan had won the Medal of Honor in World War I, served as an assistant U.S. Attorney General under President Calvin Coolidge, and was a good friend of Frank Knox, the current Secretary of the Navy. FDR sent Donovan to Britain as a special emissary to eval- uate Britain’s ability to resist. Stephenson made sure Donovan met with key British leaders, including Stuart Menzies, chief of MI-6, and Churchill himself. Donovan reported that Britain could withstand Nazi Germany and became an advocate for an independent intelligence service like the one Great Britain had. After Donovan returned from a second overseas mission to the Mediterranean Theater, Roosevelt appointed him Coordinator of Information (COI) on July 11, 1941. As Stephenson cultivated his relation- ship with Donovan and his new agency, Hoover resented his upstart rival and began to curtail his cooperation with the BSC.

At first, FDR’s eldest son James, a reserve captain in the Marine Corps, provided liaison between Donovan and other federal agencies, but immediately after Pearl Harbor he requested active duty and left his White House post. Donovan, a fellow Columbia grad, chose Cuneo to replace James as his liaison. Cuneo recalled, “I saw Berle at State, Eddie Tamm (deputy FBI director), J. Edgar [Hoover] and more often the Attorney General; on various other matters Dave Niles at the White House and Ed Foley at Treasury…. I reported to Bill Donovan … and never in writing.”

Relations between the BSC and Donovan’s COI were close, and that often led to conflict with Berle, who resented Britain’s growing influ- ence over American foreign policy, and Hoover, who saw Donovan’s agency thwarting his ability to expand the FBI’s grip on intelligence. Cuneo had to keep the lines of communication open, promote cooperation, and soothe bruised egos from time to time.

Donovan added recruits to his agency rapidly, concerned only about the talents they brought not personal backgrounds or political leanings. On June 13, 1942, the burgeoning COI was divided into two new agencies: the Office of War Information (OWI) headed by playwright and FDR speechwriter Robert Sherwood to manage propaganda efforts, and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) headed by Donovan to conduct and evaluate overseas intelligence as well as to carry out sabotage. The FBI was assigned the task of screening people Donovan hired. This allowed Hoover to put OSS employ- ees under surveillance and even plant his own agents within the organization. Hoover was quick to report any OSS screw ups and poor hiring choices to his superiors. Donovan told Cuneo that Hoover had blocked an entry visa for a hire who had “committed a few youthful mistakes.”

When Cuneo came to plead the case, the usu- ally sedate Attorney General Francis Biddle blew his top, “A few youthful mistakes?” he shouted. Hoover had compiled the man’s rap sheet, which included convictions for two counts of murder and two of manslaughter. FDR knew that “Wild Bill” Donovan had to be reined in from time to time and told Cuneo he did not want Donovan “horsing around” in a way that made trouble for the White House or the military.

Journalists, even those who supported the administration, had to contend with wartime censorship. Both Winchell and Drew Pearson often relied on anonymous sources for stories they broke in their news columns and radio broadcasts, but now official sources had to be cited for any news that could compromise mil- itary security. Sometimes they danced around the rules by claiming an item was speculation or finding a government employee to cite as a source. The Office of Censorship butted heads with Pearson more than any other reporter, marking up and filing 145 of his wartime radio scripts. In contrast, censors handled Winchell with kid gloves because they were aware he was the beneficiary of targeted leaks from the administration.

One censor complained to his boss, “Our dif- ficulty in the matter is that Winchell finds him- self in the position of being a close friend of J. Edgar Hoover and a little tin god as far as the Army and Navy are concerned.” In fact, Hoover had his own agents monitor Winchell’s broad- casts and columns to gather leads Cuneo had provided from the BSC or U.S. government sources to which the FBI was not privy.

When Pearson published a column critical of Secretary of State Cordell Hull in the wake of the resignation of Under Secretary Sumner Welles, President Roosevelt called Pearson “a chronic liar.” Concerned that the president’s comments would cut into his audience, he con- sulted his friend and lawyer Ernest Cuneo, who gave Pearson information he could use to make everyone forget the president’s remarks. In a hospital tent in Sicily General George Patton had slapped an American soldier suffering from battle fatigue. In fact, Patton had struck two soldiers in front of many witnesses in separate incidents that had been well investigated by war correspondents who chose to suppress their accounts and let General Eisenhower deal with Patton. Pearson’s November 14, 1943, broad- cast that broke the story created a storm of con- troversy over both Patton’s actions and their publication.

Later a grateful Pearson consigned an incident to his diary that could have embarrassed Cuneo. Cuneo was bringing an Italian agent from Washington to New York on a train in a bag- gage car that had been converted to a passenger coach. An overzealous rail fan snapped a photo that aroused Cuneo’s suspicion. Soon after, the man with the camera laid down his copy of Time, which was promptly picked up by another passenger. Fearing a compromising photo had been passed to an accomplice, Cuneo found an MP lieutenant and private and flashed them his OSS card and the trio followed the photographer to the men’s room where Cuneo ordered the private to break down the door.

“I can’t,” he said. “Then shoot through the door,” Cuneo demanded, but still the private refused. A frustrated Cuneo ordered the “arrest” of the entire train holding more than 700 passengers who were questioned by FBI agents as soon they arrived in New York. The suspicious photographer was detained until the wee hours of the morning and threatened to sue Cuneo. Shortly after Cuneo finally crawled into bed he was awakened by a phone call from Pear- son ribbing him about the incident after FBI Director Hoover had tipped him off.

Concerned about Gallup polls that showed FDR trailing Thomas Dewey in the 1944 pres- idential race, Churchill asked Stephenson for an independent forecast. David Seiferheld, a statis- tician with the OSS, compiled an analysis that showed Gallup was off by at least four percent. Cuneo passed on to Stephenson a prediction that showed 32 states solidly in Roosevelt’s pocket and a further eight in which he had a chance to win. “There are going to be some white-faced boys in this country,” commented Cuneo. The forecast proved remarkably accurate. FDR captured 36 states and 432 electoral votes, including wins in half of the states Seifer- held listed as potential gains.

The intelligence network for which Cuneo provided the nexus disintegrated in 1945. The first blow was President Roosevelt’s sudden death from a cerebral hemorrhage on April 12. Shortly after Germany’s surrender on May 8, President Harry Truman began making whole- sale personnel changes, and within a year hardly any of Roosevelt’s old guard remained. Truman told an aide, “Pearson and Winchell are too big for their britches. We are going to have a show- down as to who is running this country—me or them—and the showdown had better come now than later.”

Pearson and Winchell remained influential columnists for years, but their pipeline to the Oval Office had effectively been severed. Thanks to the unrelenting opposition of Hoover and the military chiefs and the lack of Congres- sional support, the OSS was dismantled by Tru- man, who gave Donovan his walking papers on September 20, less than three weeks after Japan’s surrender. Another factor in the demise of the OSS was the perception that it had been in part the creation and creature of Stephenson’s BSC. As Cuneo put it, “The British may have taught us everything we know [about intelli- gence] but not everything they know.”

During the intense period of wartime service, Cuneo met several people who became lifelong friends, including Ian Fleming, a lieutenant com- mander in British Naval Intelligence. In the sum- mer and fall of 1954, Cuneo accompanied Flem- ing on a trip across the United States as Fleming did research for Diamonds Are Forever, his fourth James Bond novel. A Las Vegas cabbie in the novel is named “Ernest Curio.”

Fleming credited Cuneo for many of the plot ideas in Goldfinger and Thunderball, dedicat- ing the latter novel “to Ernest Cuneo, muse.” However, the most important person Cuneo met was Margaret Watson from Winnipeg, one of many Canadian women Stephenson brought to New York to work for the BSC. She became Cuneo’s wife. Great Britain, Italy, and the City of Genoa decorated Ernest Cuneo for his contributions to the Allied war effort, but in the United States his relative anonymity gave him freedom.

Michael W. Williams is a resident of Vandalia, Ohio. He teaches Social Studies and English at the Miami Valley Career Technology Center in Clayton, Ohio and has a Master’s degree in History from the University of Dayton.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments