By Peter Kross

In 1939, Joseph P. Kennedy, the scion of the modern-day Kennedy family which included three United States senators, an attorney general, and the 35th president of the United States, was appointed the American ambassador to Great Britain by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Upon his appointment to the Court of St. James’s, Joe Kennedy was flung into a world on the brink of war, a conflict that he opposed and out of which he tried desperately to keep the United States. During his tumultuous time in London, Joseph Kennedy fought bitterly with the State Department, as well as FDR, in his outspoken opposition to the president’s policy of coming to the aid of Britain in the wake of Adolf Hitler’s European onslaught.

Kennedy ruffled feathers in Washington when he met secretly with German diplomats and made few friends with his anti-Semitic remarks. In the end, his opposition to America’s anti-Nazi policies led to his resignation in disgrace from his coveted ambassadorship and, for all intents and purposes, ended whatever political career he harbored for himself.

Joseph P. Kennedy’s Story of Rags to Riches

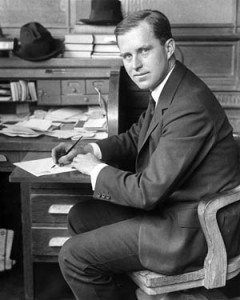

Joseph P. Kennedy was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on September 6, 1888. His grandparents had come to the United States from Ireland in the 1840s to flee the Irish famine. The political and social mores in Boston at that time separated the Irish from the Protestant “blue bloods,” effectively keeping the Irish from participating in the worlds of business and politics. As a young man, Joe delivered newspapers to make extra money, attended the Boston Latin School, and eventually was accepted to Harvard. At Harvard he was an excellent baseball player but still suffered discrimination because of his Irish heritage. Before graduating, he made a promise to himself that he would become a millionaire by age 30. That he did––and more.

Shortly after his graduation from Harvard, Joe was hired as a bank examiner and received a hands-on education in how banks and financial institutions work. His first big break came when he was able to resist the takeover of the Columbia Trust Bank, the only Irish-owned bank in Boston. At age 25, Joe was appointed president of Columbia Trust.

During World War I, Joe, to avoid military service, obtained a job with Bethlehem Steel’s Forge River shipbuilding plant in Quincy, Massachusetts, an industry that was deemed vital to winning the war. There he was appointed to the position of assistant general manager. (Read more about the First World War and other events prior to WWII inside Military Heritage magazine.)

His next job was with the brokerage house of Hayden Stone and Company in Boston. Through shrewd business practices, Joe amassed a small fortune, and he bought a home for his family in Brookline, a suburb of Boston. In what would be called “insider trading” today, Joe was able to buy and sell stock using information obtained from his colleagues before that information got out to the general public. Joe pulled most of his money out of the stock market before it crashed in October 1929.

Between his business successes, in 1914 he married Rose Fitzgerald, the daughter of Boston’s popular and gregarious mayor, John Francis “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald.

From Hollywood to the Mafia

Using his now considerable fortune, Joe branched out and began producing Hollywood movies. Most of the films he produced were not big hits, but he made more contacts with the Hollywood moguls, who would add another layer of legitimacy to his already bourgeoning portfolio.

If Joe flopped in Hollywood, he more than made up for it when it came to the distribution of liquor during Prohibition. There are no documents that positively link Joe Kennedy to the illegal distribution of liquor during the time when America was “dry,” but allegations by prominent mob figures of the time tell a different story. In 1922, during Joe’s 10th Harvard reunion, he purportedly brought a large stock of scotch for his guests. According to one person who attended the party, Joe had the scotch brought in by boat right on the beach at Plymouth, saying, “It came ashore the way the Pilgrims did.”

According to the late mobster Frank Costello, one of the most prominent members of organized crime during that period, he and Kennedy were in a silent partnership during Prohibition and were visible in keeping bars and saloons overflowing with illegal booze. Costello told author Peter Maas (who was writing a book on Costello’s life––a book that was never completed due to Costello’s death) that Kennedy had a monopoly when it came to the importation of liquor into the United States.

Joe Kennedy later ran a legitimate liquor distributorship called Somerset Importers Ltd. In 1933, Kennedy sailed in London prior to the end of Prohibition in the U.S. and emerged as the sole American distributor of two brands of scotch, as well as Gordon’s Gin. In 1946, Kennedy would sell Somerset Importers for a hefty $8 million.

Joe Kennedy in the Democratic Party

Besides his business interests, it was politics that drove Joe Kennedy into the public spotlight. He had always harbored ambitions to be the first Catholic president of the United States but despite his increasing fortune the blatant anti-Catholic resentment he encountered in Boston remained the ultimate obstacle to his ambitions.

His first foray into national politics came in 1918, when he contributed money to his father-in-law’s campaign for Congress. Joe was also an early supporter of another rising star in the Democratic Party, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Joe traveled with FDR when the New York governor, then campaigning against President Herbert Hoover, was making a swing around New England. Joe relished the sights and sounds of the campaign and believed that his future lay in FDR’s success.

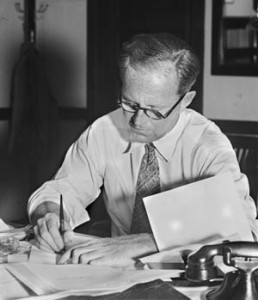

After Roosevelt’s election in 1933, he offered Joe the ambassadorship to Ireland, but the latter turned it down. The next July, FDR appointed Joe to head the newly created Securities and Exchange Commission, a body that would oversee Wall Street and stop illegal trading among its members.

Joe’s appointment as head of the SEC was an unusual one, to say the least. He was not well liked by the leading members of Wall Street due to his less than honest approach to gaining his fortune––not to mention his alleged ties to mobsters during the Prohibition era. But Joe surprised many of his critics and for the next 14 months did a more than adequate job of keeping unethical business practices from taking over the securities industry.

In 1937, Kennedy left the SEC and took a job as chairman of the Maritime Commission. His principal achievement was to break the deadlock between the powerful labor unions and the ship owners. Speaking of this time, Joe said that it was “the toughest thing I ever did in my life.”

Ambassador to Britain: Pledging American Neutrality

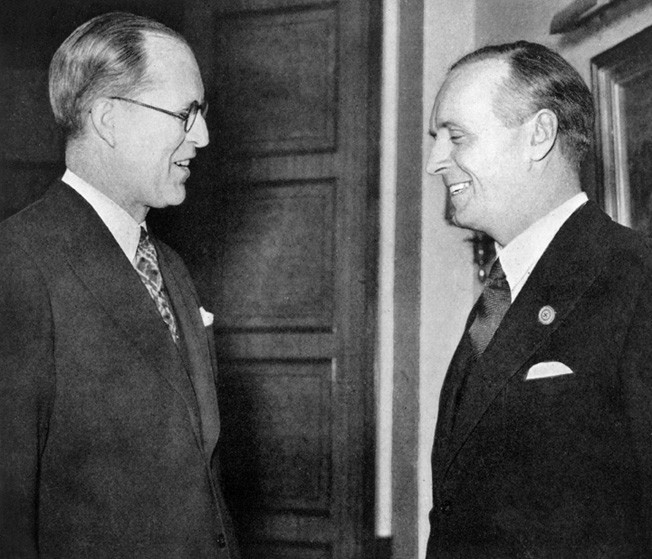

In 1938, President Roosevelt appointed Joe Kennedy as the U.S. ambassador to Great Britain, an extraordinary post that put him in the spotlight of international affairs. For Joe, the appointment was the fulfillment of a lifetime of work in the political realm, a chance to put to rest all the slights he felt as a Catholic outsider in Boston society.

But if Joe believed that his nearly two-year stint as head of the Maritime Commission was tough, the ambassador’s post was to prove far tougher and more demanding than he ever imagined and ruined whatever ambitions he harbored for a political future for himself.

What neither Joe Kennedy nor anyone else could predict, as he and his large (nine children) and gregarious family arrived in Britain on March 1, 1938, was that one year later all of Europe would be embroiled in another full-scale war.

At 49 years of age, he was now pulled directly into a line of fire that few U.S. ambassadors ever had to endure; much of it was of his own making. For example, he made his first public speech in England at London’s Pilgrim Club, whose attendees were the leading figures in British politics and business. He startled the audience with his comments in which he said that it was in America’s best interests to stay neutral in any coming conflict with Germany and that the U.S. would not see eye to eye with Britain as it had done in the past. Those were strong words for an ambassador to say to the citizens of the country in which he was residing.

Naturally, Joe’s remarks caused quite a stir in the British press as well as in Washington. In a letter to his friend Bernard Baruch, Kennedy said that he wanted to “reassure my friends and critics alike that I have not yet been taken into the British camp.” In time, Kennedy’s actions would cause more consternation and irritation across both sides of the Atlantic.

From Phony War to Blitzkrieg

War clouds were building over Europe. In September 1938, after the Anschluss with Austria, Adolf Hitler annexed the German-speaking portions of Czechoslovakia, and then, a year later, Hitler’s blitzkrieg overran Poland, setting off a major crisis in both London and Paris as to how to respond to Germany’s aggression. A year earlier, Britain had given Poland its assurances that if it were attacked by Germany, Britain would come to her aid. In the days and months after the German invasion, neither France nor Britain took any forceful military action against Germany.

This period was known as the Phony War––when the British and French armies stood their ground and let Germany prepare to gobble up the rest of Europe. In time, German forces invaded both Norway and Denmark. By the middle of 1940, Hitler’s troops successfully marched on Belgium and Holland. In June, Hitler rode triumphantly into Paris, the conquered City of Light. With the fall of France, Britain stood alone against Nazi Germany’s tyranny. The United States did not enter the war for another year and a half.

When Paris fell, the German commander in that city made a courtesy call to the American military and naval attaches at the U.S. embassy, and brought with him the “very best brandy in the Grillon [the Hotel Grillon––the residence of the German military command in Paris].”

The FBI’s File on Joe Kennedy

The FBI, under the leadership of J. Edgar Hoover, opened a file on Joe Kennedy as it did with many other prominent people. Joe Kennedy’s FBI files are now available to the public and show the extent of the interest the FBI had in him. One unidentified person wrote the following on Ambassador Kennedy:

“(Blank) described Mr. Kennedy as a man with a very dynamic personality who was brilliant that he feels there is not a more patriotic man in the United States than Mr. Kennedy.

“He said that Mr. Kennedy is a man whose temperament is such that he easily becomes angry, and that during the time he is angry, he does not care what he says. He stated, however, that he does not believe that even during a period of anger, Mr. Kennedy is the type of man who would reveal any information which would be detrimental to the interests of the United States.”

An FBI memo dated April 28, 1947, from Director Hoover to his aide, D.M. Ladd, gives more information on the Bureau’s relationship with Ambassador Kennedy: “In June 1938, Special Agent (Blank) advised that he had received very cordial treatment from Ambassador Kennedy in London, while (Blank) was there visiting Scotland Yard. Kennedy’s Ambassadorship to Britain is widely regarded in the United States as demonstrating that Kennedy was an appeaser and believed that Britain would lose the war. His appointment during this period is thought to be important only as it throws light on his present views about Russia as reported by Mr. Arthur Krock.

“Arthur Krock, of the New York Times … described Kennedy as spokesman for a group of industrialists and financiers, who believe that Russia should not be opposed at any point. All energies should be devoted to keeping America prosperous.”

The FBI was interested in using Joe Kennedy as a source of information, and the memos from that time spell out what they hoped to gain from his knowledge of world affairs. On October 18, 1943, after Kennedy ended his role as ambassador to Great Britain, Hoover wrote the following memo to the special agent in charge in the FBI’s Boston office:

“In the event you feel that Mr. Kennedy is in a position to offer active assistance to the Bureau such as is expected of Special Service Contacts, there is no objection to utilizing him in this capacity. If he can be made use of as a Special Service Contact, the Bureau should be advised as to the nature of the information he is able to provide, or the facilities he can offer for the Bureau’s use. Every effort should be made to provide him with investigative assignments in keeping with his particular ability and the Bureau should be advised the nature of these assignments, together with the results obtained. “

Despite the work that Ambassador Kennedy did for the Bureau (the records do not reflect exactly what he did), Director Hoover “recommended that the meritorious service award not be awarded to Mr. Joseph P. Kennedy for the reason that he has not affirmatively actually done anything of special value to the Bureau despite his willingness to perform such services.”

“Jittery Joe”

If there was a course in diplomacy, Joe Kennedy either did not know it existed or forgot to attend. That is really not what happened, but over time the new ambassador’s actions and rather indiscreet remarks would make FDR cringe. Examples of this include Joe Kennedy’s blatant anti-Semitic remarks. For a person who suffered from religious discrimination while a young man living in Boston, Kennedy was either too naïve or really didn’t understand what his words meant, especially coming from someone in such a high position.

For four months after his arrival in London, the ambassador tried to arrange a meeting with Adolf Hitler through the German ambassador to Great Britain, Herbert von Dirksen. In his meetings with von Dirksen, Kennedy spelled out his personal animosity toward the Jewish people. In reaction to the Germans’ “Final Solution to the Jewish problem,” which was causing such an uproar in Western countries, Kennedy told von Dirksen that in his opinion, “it was not so much the fact that we [i.e., Germany] wanted to get rid of the Jews that was so harmful to us, but rather the loud clamor with which we accomplished this purpose.”

The ambassador’s remarks were picked up and reproduced in the United States, much to the chagrin of the president. However, if FDR believed that his ambassador was finished making anti-British and anti-Semitic remarks, he was badly mistaken.

Kennedy did not endear himself to the British population during German air raids on London. As the Blitz attacks grew stronger, the ambassador moved his family out of London to escape the raids. After touring the destruction in London, he remarked at how much he admired the local citizens for their bravery and fortitude in the face of such horrific German attacks. In time, the papers began calling Kennedy, “Jittery Joe.”

Leaving Great Britain

Believing that his effectiveness as ambassador was coming to an end, Kennedy, on October 6, 1940, wrote a letter to FDR asking that he be relieved of his duties in London and demanded that he be brought home. If his request was denied, he would come home anyway. The Roosevelt administration accepted Kennedy’s wishes, and he arrived in New York on October 27, arriving at La Guardia Airport. FDR had asked Joe and Rose to come to see him at the White House when they arrived, and they took the train to Washington immediately. After dinner, Joe gave the president a piece of his mind. He told FDR that he did not like the way he was treated in London, saying candidly that he was kept out of the loop as far as policy formulation was concerned. He took a direct swipe at the State Department, saying it was directly responsible for his being shut out of policy making.

Joe arrived home one month before the 1940 presidential election in which FDR was running for an unprecedented third term. The press was aware of the growing rift between FDR and Kennedy, and speculation was the order of the day when it came to what trouble Kennedy might inflict on the campaign. Joe agreed to make a radio speech endorsing the president, which he paid for himself. It cost $20,000 for a nationwide hookup. He endorsed FDR but said that he still believed it wise for the U.S. to stay out of the European war.

Joe officially resigned as U.S. Ambassador in February 1941, one month into FDR’s third term. His final remarks were, “Having finished a rather busy political career this week, I find myself much more interested in what young Joe is going to do than what I am going to do with the rest of my life.”

“Democracy is Finished in England”

As the Roosevelt administration was debating whether or not to grant military aid to Britain (a March 1941 Lend-Lease deal would eventually send 50 obsolete destroyers to Great Britain in exchange for leases from the British of a number of bases in the Caribbean), Kennedy publicly spoke out against any such U.S. action. He chilled both Washington and London with his comments, “Democracy is finished in England. It may be here,” referring to the United States. His remarks were published in the Boston Sunday Globe on November 10, 1940.

Kennedy further embellished his remarks on the subject of the future of democracy in the U.S. and Britain with the Boston Globe’s Louis Lyons and Ralph Coglan of the St. Louis Post Dispatch. He said of the situation in Europe, “It’s all a question of what we do with the next six months. The whole reason for aiding England is to give us time. As long as she is there, we have to prepare. It isn’t that she’s fighting for democracy. That’s the bunk. She’s fighting for self-preservation, just as we will if it comes to us. I know more about the European situation than anybody else, and it’s up to me to see that the country gets it.”

He spent his time planning the political future of his two eldest sons, Joe Jr., and John. But, as fate would have it, his hopes and aspirations for his sons were caught up in the tragedies of war.

The war that Joseph P. Kennedy so deeply tried to avoid resulted in the deaths of his eldest son, Joe Jr., who was killed while on a secret mission over Europe, and his son-in-law, William “Billy” Hartington, the Marquess of Hartington, who married his daughter Kathleen. It almost cost John his life in the Solomon Islands after his PT-109 was rammed by a Japanese destroyer.

John F. Kennedy later became the 35th president of the United States––a job that Joe once hoped would be his own. Kennedy’s isolationist views and pro-German remarks came at a high personal price. For a man with limitless ambitions, his fall from grace must have been the cruelest cut of all.

Accurate, compact and appropriate.

I am a loss to explain how Roosevelt came to appoint a man whose enmity for the British was so strong. This mistake was rectified but almost too late to repair the damage done to relations between the two countries.