By Peter Kross

By June 1940, during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s seventh year in office, Europe was ablaze. In that month, France fell to the Nazi blitzkrieg that threatened to overtake the entire continent. In the previous year Hitler’s troops and tanks had overrun Poland. The Nazi dictator’s vision of world domination was now in his grasp, and only Great Britain stood in defiance of Germany. The German general staff was preparing a secret plan, code-named Operation Sea Lion, to invade England. All along the British coast, fortifications were being erected to repel the expected cross-Channel assault.

However much Hitler’s generals wanted to invade England, the Führer still harbored wishes for an Anglo-German alliance against the greater enemy, the Soviet Union, and wanted to spare the tiny island the horrors of an invasion. He attempted by clandestine means to send peace overtures to the British government. To his disappointment, London resoundingly declined his offers.

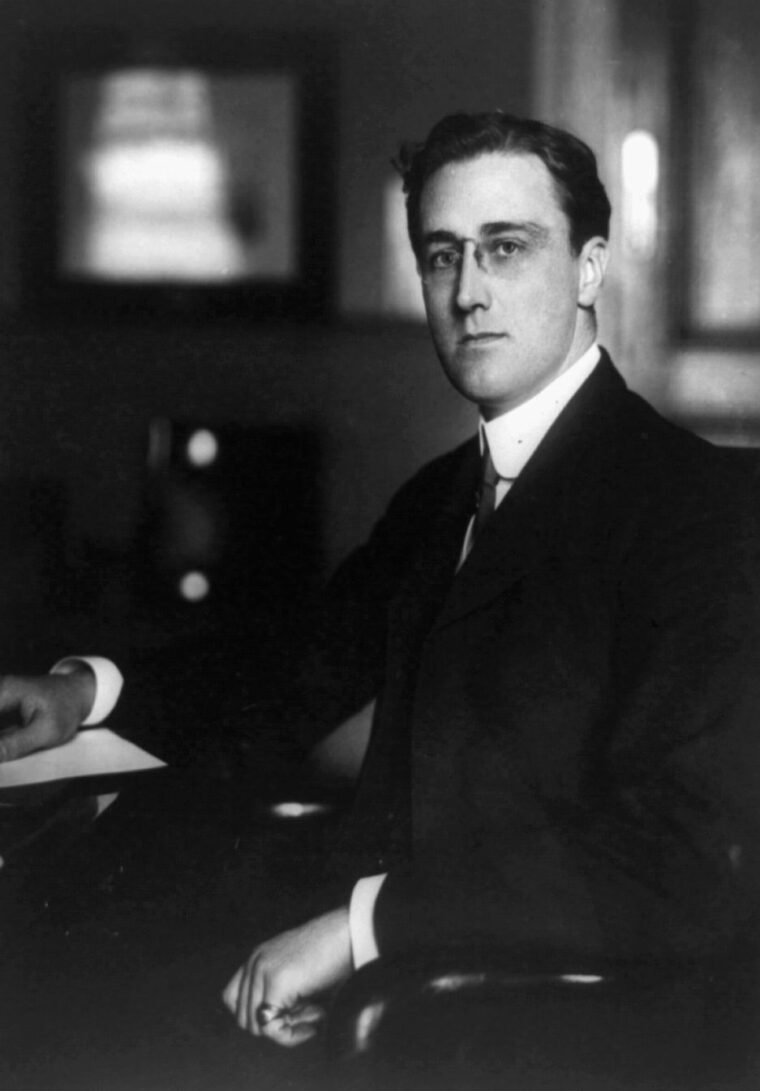

Across the Atlantic Ocean, the United States was officially neutral. By 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had been elected twice and was campaigning for an unprecedented third term in the White House. Speaking to the county in person and via his fireside chats, he said that the United States did not want to send its boys to fight in any European conflict. The president’s rhetoric was for public consumption only. In private, he was doing everything possible to join the struggle against Hitler, thus undermining the policy of neutrality that America had espoused since the beginning of the war.

To that end, FDR and Prime Minister Winston Churchill had for some time been exchanging personal correspondence on all sorts of matters, both private and military. In their voluminous letters, the prime minister referred to President Roosevelt as POTUS (President of the United States), while FDR called Churchill “Former Naval Person.” Anyone reading their correspondence would have been shocked as to how far the American leader was going, secretly making plans for the shipment of surplus war materials to Great Britain and positioning the United States to eventually join Great Britain as an active participant in the war against Germany.

If the president’s wartime relationship with Winston Churchill was one of mutual trust and admiration, their first encounter did not turn out so well. The two men had first met 21 years previously when a young Franklin D. Roosevelt traveled to England. In later years, President Roosevelt told Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy, “I have always disliked him [Churchill] since the time I went to England in 1918. He acted like a stinker at a dinner I attended, lording it all over us.”

Two decades later, with the clouds of war now squarely over England, then-Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain appointed Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty. Like Churchill, FDR was part of his country’s naval establishment, serving as assistant secretary of the Navy under President Woodrow Wilson in 1913 at the tender age of 31. In this role, Roosevelt turned his attention to an area in which he was well versed and interested in pursuing further—espionage.

Roosevelt built up the only national intelligence agency the United States had at the time, the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI). ONI officers were posted to various countries across the globe to gather intelligence. FDR was obsessed with the possibilities of domestic subversion and home-grown violence perpetrated by foreign agents. As an example, he pointed to the Black Thom explosion in New York harbor on July 30, 1916, in which German agents blew up millions of dollars worth of ammunition bound for Allied troops in Europe during World War I. Seven men had been killed and 35 injured.

To gain a firsthand view of the war, Roosevelt visited England. Upon arrival, he met with Sir Reginald “Blinker” Hall, the director of British Naval Intelligence. For FDR, this meeting with one of the preeminent spymasters of the time was heady stuff. FDR was given access to Room 40, the top-secret bastion of British naval intelligence where the largest navy in the world was sent out to protect the empire. Hall shared with Roosevelt just enough highly classified information to whet Roosevelt’s appetite for anything clandestine. Upon his return home, FDR vowed to transform the nascent American ONI into an organization similar to its British counterpart.

Almost 20 years passed before Franklin D. Roosevelt contacted Churchill in an official capacity. One week after Great Britain declared war on Germany, FDR wrote to Churchill and asked if it would be possible for the two men to begin secret, personal communications. FDR wrote, “It is because you and I occupied similar positions in the World War that I want you to know how glad I am that you are back again in the Admiralty. What I want you and the Prime Minister to know is that I shall at all times welcome it, if you will keep in touch personally with anything you want me to know about. You can always send sealed letters through your pouch.”

FDR Watched in Horror as Hitler Conquered Most of Europe and Threatened England

On May 10, 1940, the government of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain resigned, and Churchill assumed residence at 10 Downing Street. The “Former Naval Person” was now Roosevelt’s contemporary in power.

From across the Atlantic, FDR watched in horror as Hitler conquered most of Europe. Hitler knew that if he conquered England Germany would dominate the European continent for years to come. FDR knew that something had to be done to ensure England’s survival, and his letters to Churchill showed how much he understood his friend’s plight.

On May 16, 1940, a message between the two men revealed how far the United States was willing to go to aid Britain. Churchill told the president that to keep the sea lanes free of marauding German U-boats that had been wreaking havoc on British supply ships, he needed from the United States 50 old destroyers that were no longer in the active American fleet. The president told Churchill that he had no problem with the destroyer deal but that he had to get congressional authorization, which, at the time, was highly unlikely.

In the United States, a loud chorus of isolationists in Congress was pressing the Roosevelt administration to stay out of the war in Europe. In the 1930s, Congress had passed a number of bills that prevented the United States from supplying war materiel to combatants and refused to provide loans to any nation that had defaulted on its debts from World War I. The isolationist sentiment was so strong that in 1938 a constitutional amendment was proposed requiring the American people to vote before war was declared.

Despite the isolationist sentiments in Congress, the president decided on a different course of action. On April 20, 1939, FDR told his staff in a confidential meeting, “We are going to have a patrol from Newfoundland down to South America and if some submarines are lying there and try to interrupt an American flag, and our navy sinks them, too bad … If we fire and sink an Italian or German, we will say it the way the Japs do, So sorry. Never happen again. Tomorrow we sink two.”

In June 1939, three months before Germany invaded Poland, King George VI of England arrived in the United States and met Roosevelt at his home in Hyde Park, New York. During their discussions, the president said that should war erupt between Germany and England, the U.S. would fully support England militarily.

The destroyer deal was a victory for the Roosevelt administration. In return for signing over the outdated warships, the British allowed the United States to use a number of their bases in the Caribbean for military purposes. During the war, these strategic bases would play an important part in tracking the German U-boat fleet, which prowled the waters of the Western Hemisphere.

Although FDR’s policies regarding secret military shipments to England were positively endorsed within the upper echelons of Churchill’s government, the U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain, the outspoken and controversial Joseph P. Kennedy, did not share their enthusiasm. Kennedy, a wealthy, Irish-Catholic millionaire from Boston who had reputedly made his fortune in the bootlegging business during Prohibition, had visions of becoming the first Catholic president of the United States. Being named ambassador to England, then the most prestigious assignment in the foreign service, was, in Kennedy’s mind, the first step toward the White House.

The Kennedys were immensely popular when the new ambassador presented his credentials to the king. He brought to England with him his large and gregarious family, including his two eldest sons, John and Joe Jr., whom he made his personal secretary. They were the hit of the social circuit, going to the best parties British society could offer and meeting the upper crust of the kingdom.

While the British may have loved Joe Kennedy and his dashing family, FDR had a vastly different view of his new ambassador. Before getting the London post, Joe Kennedy had lobbied Washington for the job of Secretary of the Treasury. Instead, FDR gave that most vital post to Henry Morgenthau who became a confidant of the president. Joe Kennedy was no intimate of the president, as time would show.

Kennedy was against any U.S. involvement in the European war and made no bones about how he felt. His public statements in support of American neutrality left many members of the Roosevelt administration shaking their heads. In FDR’s eyes, Kennedy was getting out of step with the administration’s foreign policy.

In December 1939, Kennedy returned to the U.S. for consultations with the State Department and the president. Kennedy told FDR that, in his opinion, Churchill was “ruthless and scheming” and would do anything to get America into the war. He further told the White House that Churchill was allied with certain “Jewish leaders” who wanted nothing better than to get America into the war. Kennedy’s blatant anti-Semitism was now out in the open, and his daily utterances made life difficult for the president.

“I Never Want to See That Son of a Bitch Again as Long as I Live. Take His Resignation and Get Him Out of Here.”

During his stay in Washington, Kennedy had a meeting with Bill Bullitt, U.S. Ambassador to France. Kennedy told Bullitt that Britain and France were finished as sovereign countries, that Germany would win the war, and that there was nothing the United States could do to stop that from happening. Kennedy’s comments were funneled back to the White House, and FDR reportedly said, “I never want to see that son of a bitch again as long as I live. Take his resignation and get him out of here.”

Kennedy was now officially out of the Roosevelt administration and was replaced by a man more in tune with FDR’s political program, John Winant, a Republican businessman who had none of the baggage that Kennedy carried. Winant was a facilitator between the president and Churchill.

In Washington, the administration was pushing ahead with the Lend-Lease Bill. The man responsible for drafting the bill was Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau. The administration got its way in most respects, including the right of American naval vessels to go on convoy duty, protecting ships heading for Europe. Roosevelt was also empowered to send military aid to the Soviet Union if that country were attacked by Germany.

The bill passed Congress easily, and Churchill called it “the most unsordid act in the history of any nation.” By the time the war ended, the Lend-Lease program had sent between $40 and $50 billion worth of military aid to Allied countries. At the time Lend-Lease was signed it sent an unmistakable signal to Hitler that the United States was not going to allow England to be defeated without a fight.

While the debate over Lend-Lease was going on, covert meetings between American and British military leaders were taking place in Washington. In the summer of 1940, high-ranking American and British military commanders met to plan strategy in case the U.S. was brought into the war. These secret talks were called ABC-1, American-British Conversations, and were conducted away from the prying eyes of both the Congress and the American people.

While these secret military and political negotiations were going on, the president was running for re-election to a third term in 1940. His public rhetoric did not match his clandestine words and deeds regarding covert overtures to the British. At a campaign rally in Boston a few days before the November election, the President told the cheering throngs, “I have said this before, but I shall say it again and again. Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.” He repeated the same message in Brooklyn, stating, “I am fighting to keep our people out of foreign wars. And I will keep fighting.” During stops in upstate New York, Roosevelt kept up the same anti-interventionist theme. “Your national government is equally a government of peace—a government that intends to retain peace for the American people.”

If the president thought he was going to be campaigning against an antiwar Republican candidate, he was wrong. The GOP nominated Wendell Willkie, a native of Indiana and now a successful New York businessman. Willkie shared FDR’s position on aiding the British and that potentially inflammatory issue never surfaced. Roosevelt became the first American president to be elected to a third term in the White House. He was now able to use all his influence to align the United States covertly behind Britain in her war against Germany. The actions FDR took between November 1940 and December 7, 1941, still one full year in the future, laid the cornerstone for American participation in World War II.

Working in conjunction with Winston Churchill, FDR took definitive steps in the year before Pearl Harbor to solidify American aid to Britain and prepare the United States for war. These included the initiation of naval patrols by American warships in the Atlantic Ocean beginning in April 1941. If an American ship spotted a patrolling German U-boat, the position of that submarine was to be instantly relayed to British ships in the area. Further, American naval units were dispatched to the coast of Ireland as a show of solidarity with the government in London. Ireland was not fully in support of the British in the war with Germany, and the Churchill government feared that the Germans would use Irish soil as a jumping-off point for an invasion of England. Congress passed a bill on September 16, 1940, which initiated a peacetime draft, the first one in American history.

Other provocative actions by the Roosevelt administration included the use of American naval ships as escorts for merchant ships of other nations sailing between the United States and Iceland and a presidential declaration signed on September 11, which authorized American warships to shoot at any German submarine that initiated hostile action. Through the so-called “ABCD” agreement, the United States pledged to come to the aid of Britain if that country were attacked by Japan in the Southwest Pacific.

The president had ordered the development of a series of war plans addressing numerous potential scenarios. The Rainbow 5 plan was a comprehensive blueprint for U.S. involvement in a European conflict. Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall had led the effort to complete the plan, which carried the official name of “Army and Navy Estimate of United States Over-All Production Requirements.” Marshall’s report to the White House was staggering in its military implications. To fight and win a global war, the United States would require 216 infantry divisions, 51 motorized divisions, and a large navy capable of covering the world’s oceans. The pricetag for this huge military buildup was an astronomical $150 billion.

On December 5, 1941, the Rainbow 5 plan was leaked to the press and published in the anti-Roosevelt Washington Times Herald. Readers were treated to a screaming headline: “WAR PLANS’ GOAL IS TEN MILLION ARMED MEN. PROPOSED LAND DRIVE BY JULY 1943.” Before the fallout from the Herald’s bombshell could make any further trouble for the administration, the magnitude of the story was overshadowed by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor three days later.

On July 25, 1941, Roosevelt froze all Japanese assets in the United States. Days after this action was taken, the governments of Britain and the Netherlands East Indies took similar actions. This was, in reality, an act of economic warfare by the United States against Japan. The Roosevelt administration soon took the further hostile measure of enforcing a total trade embargo against Japan. The embargo was literally a stranglehold on the Japanese, who now had to look elsewhere in the world for the precious oil that fueled an ever-growing military machine.

In August 1941, Roosevelt and Churchill met at Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, and agreed to the principles of the Atlantic Charter. To pave the way for a summit meeting between the two, the president sent Harry Hopkins, one of his most trusted aides, to London to make arrangements. Churchill arrived aboard the battleship HMS Prince of Wales, while Roosevelt reached the location aboard the cruiser USS Augusta.

Their conference focused on two important items: the conduct of the war in Europe and how the political climate of the world would look after hostilities ended. One of the agreements coming out of the meeting was a decision by the Americans to allow U.S. naval vessels to provide escort for shipping as far away as Iceland. As of September 16, 1941, it became the policy of the United States that if any American naval ship was attacked by a German U-boat, immediate retaliation was in order. That decision was the unofficial beginning of American participation in the war. It was also decided that American and British commanders would meet to formulate military policy, even though the United States was not technically involved in hostilities.

In the end, Roosevelt and Churchill agreed on a number of fundamental policies to govern a postwar world. Among them were the basic freedoms of worship and speech and a dedication to a postwar international organization similar to the old League of Nations, but which would have more power to settle international disputes. The other principles in the declaration were self-determination and economic liberalism. Self-determination called for the freed populace of any nation to choose its own way of life and form of government. This notion did not sit well with either the British or the Soviets. The British did not want to lose their mighty worldwide empire, while the Soviets did not want to take the chance that any liberated nations in Eastern Europe would choose democracy over communism. The term “economic liberalism” was more benign in its concept. It called for free trade among nations and freedom of the seas.

American Pilots Were Paid $500 Per Month, as Well as an Extra $500 for Every Japanese Plane They Shot Down.

Churchill came away from the meeting convinced that “FDR was obviously determined” to enter the war at some point in the future. Like the other clandestine steps taken by the American president to align the United States with England, the principles spelled out in the Atlantic Charter were another step on the road to open American involvement in the war.

In October 1941, the U.S. rejected offers by the Japanese government that would have ended the economic embargo. In a message dated November 26, 1941, the U.S. further called for the unconditional pullback of Japanese forces in Indochina and the Far East, and the renunciation by Japan of the use of force in the region.

The United States also allowed former American military pilots to carry out covert aerial attacks against Japanese forces in the Far East on behalf of the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang, the Nationalist leader, asked the Roosevelt administration for a large force of 500 bombers from the American arsenal to be used in a military campaign against Japan. Roosevelt thought that this was too much of a provocation against Japan and decided to scale down the request instead of canceling it outright.

The president had tasked Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau to meet with certain representatives of the Nationalist government, including T.V. Soong, the ambassador to the United States, and Claire Chennault, a onetime U.S. Army Air Corps officer and the current American air advisor to Chiang. In December 1940, a secret agreement was formulated between the White House and Chiang’s representatives whereby a number of furloughed American Air Corps pilots, along with 100 Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk pursuit planes, were loaned to the Nationalists to carry out military actions against the Japanese. The American pilots were paid $500 per month, as well as an extra $500 for every Japanese plane they shot down. This secret air unit earned the nickname of “The Flying Tigers.” The Chiang-Roosevelt agreement was not revealed to the public until the war was over.

Some revisionist historians have speculated that FDR was aware of the impending attack on Pearl Harbor. In historical hindsight, such assertions are not based on fact. A more accurate description of events is that the intelligence gathered was misinterpreted or mishandled. The air and seas commanders in Hawaii were kept largely in the dark until the fateful morning of December 7, 1941.

While the president was pursuing prewar goals, he followed up on another avenue to further U.S.-British covert relations. He wanted to create a covert intelligence-sharing arrangement with the British government, and the man he appointed to lead this effort was World War I hero William “Wild Bill” Donovan, a Republican lawyer from New York. Donovan’s most important champion in the Roosevelt administration was Republican Frank Knox, whom FDR appointed to be his Secretary of the Navy. On Knox’s advice, President Roosevelt asked Donovan to come to the White House for a meeting. Donovan met with the Secretaries of War, State, and the Navy. At the end of the conference he was asked by the administration to make a trip to Britain “to learn about Britain’s handling of the Fifth Column problem.”

Donovan accepted, and on July 14, 1940, he left New York as the personal representative of the president of the United States. Accompanying Donovan to London was a reporter from the Chicago Daily News, Edgar Mowrer. The ostensible reason for their trip was to report on the activities of Fifth Columnists in England and how the government was tackling the situation. Donovan’s trip to England was unprecedented for a civilian. He arrived with letters of introduction from prominent Washington luminaries. Before his departure, Donovan dined with Lord Lothian, the British ambassador to the United States.

Donovan’s secondary purpose was to learn as much as possible about the military situation in England. He inspected many British military installations, spoke with their commanders, and came home with a recommendation that the United States do as much as possible to aid England militarily. William Stephenson, Britain’s Passport Control Officer in the United States, pulled considerable strings with his contacts in British intelligence, asking that the British secret services give as much time to Donovan as he needed.

Donovan met with all the top military and political leaders of the country, including Prime Minister Churchill, King George VI, and most importantly, Stewart Menzies, the head of British Intelligence. Menzies took Donovan under his wing, imparting many of England’s most vital intelligence secrets, including the code-breaking operation at Bletchley Park and the existence of Ultra, the means by which the British decoded much of Germany’s military wire traffic.

The other important British intelligence official Donovan met with was Rear Admiral John Godfrey, head of Naval Intelligence. Godfrey introduced Donovan to his naval aide, Commander Ian Fleming, who would later accompany Godfrey to the United States to help the U.S. design its own intelligence division. Fleming would later use his wartime experiences to create his fictional spy, James Bond.

Donovan was so impressed with Godfrey that upon returning to Washington he urged the president to appoint a person who would travel back and forth between England and the Untied States in a liaison capacity. He also urged full cooperation in intelligence sharing.

Donovan listened as his British counterparts asked for military help and assured him that if America gave England the tools of war necessary to defend itself, they would be able to stave off the Germans. Donovan returned to the United States on August 4 and met with Secretary Knox the following day. Over the next several days, he also met with other important military and political representatives of the president, including members of Congress who had been briefed on his trip.

The New York Times Reported That Donovan was Off on “Another Mysterious Mission.”

Donovan traveled with the president to Hyde Park and reported on all he saw and did while in Britain. He told the president that in his opinion the United States should give the British all the military help necessary to win the war. As for the official reason for his trip to England, to study Fifth Column activities, Donovan and Mowrer wrote a number of articles on the dangers of such activity, which were published in the nation’s press. FDR was successful in hiding from the public the real reason for sending Bill Donovan to England.

Also unknown to the public, and with the permission of the president, Donovan began a working relationship with William Stephenson, Britain’s master spy in the United States. Donovan was a frequent visitor to the New York headquarters of Stephenson’s BSC, British Security Coordination, located at Rockefeller Center. Soon, the two men joined forces in an unofficial intelligence-sharing alliance. Donovan gave an account of his work with Stephenson to FDR, and in December 1940, FDR asked Donovan to once again travel overseas as his personal emissary.

Donovan’s official presidential authorization was to “make a strategic appreciation from an economic, political, and military standpoint of the Mediterranean area.” Stephenson accompanied Donovan, leaving Baltimore for Bermuda on December 6, 1940. The New York Times reported that Donovan was off on “another mysterious mission.”

Due to bad weather in the Atlantic, the two men were forced to stay in Bermuda for eight days. This time was really a boon to Donovan in learning how the British operated foreign intelligence. The island of Bermuda was a vital British listening post, which intercepted radio messages from around the world in transit to the Western Hemisphere. Mail arriving from Europe was intercepted and read, giving British intelligence an upper hand in tracking down Nazi sleeper rings in the Americas.

In England, Donovan met with Prime Minister Churchill. He was then off to Gibraltar, Portugal, Bulgaria, Malta, Egypt, Greece, and other places of interest. Donovan’s hosts all asked him for military and economic aid in order to stave off defeat. Returning to the United States on March 18, 1941, he soon found himself debriefing the president and his cabinet on the long voyage. He told his listeners that the British would be able to defeat the Nazis with adequate support.

It was also during this trip that British intelligence agents approached Donovan with the idea of a centralized American intelligence agency. Donovan presented the idea to FDR, but military leaders met it with open hostility.

General Sherman Miles, head of Army Intelligence, wrote to General Marshall, “In great confidence O.N.I. (Office of Naval Intelligence) tells me that there is considerable reason to believe that there is movement on foot, fostered by Col. Donovan, to establish a super agency controlling all intelligence. This would mean that such an agency, no doubt under Col. Donovan, would collect, collate, and possibly even evaluate all military intelligence which we now gather from foreign countries. From the point of view of the War Department, such a move would appear to be very disadvantageous, if not calamitous.”

Despite the military’s objection, President Roosevelt took the first tentative step in the creation of an American espionage establishment when he appointed William Donovan as head of an intelligence-gathering body called COI, Coordinator of Information. In his new capacity, Donovan would begin to build up America’s secret intelligence-gathering empire.

Even before a shot had been fired in anger against the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was inching America ever closer to war. Historians have debated the nature of Roosevelt’s actions. However, perhaps the term that describes them best is “pragmatic.” While the United States may not have been fully prepared for war on December 7, 1941, Roosevelt had come to the conclusion that war with both Japan and Germany was virtually inevitable.

Peter Kross is the author of Spies, Traitors and Moles: An Espionage and Intelligence Quiz Book and The Encyclopedia of World War II Spies.

You are aware that William Stephenson was Canadian? Mentioning that would have provided more nuance to your story than leaving it out.

It’s exceedingly frustrating that so many articles of this sort can’t be bothered to imagine that countries other than the USA and Great Britain helped win WW2. Both so called American and English historians are famous for this.

You might also have mentioned that the Royal Canadian Navy was carrying out half of the convoy escort work between North America and Britain.

Other than that, an interesting read.

This particular article is about Roosevelt’s efforts in the U.S. We have published a variety of stories on Canadian contributions to the Allied effort, and you’ll find Canadians mentioned in many other stories. We attempt to cover a wide variety of topics in our print magazines and website, and many of these topics deserve a book or two — certainly more than we can devote in one magazine article, even at 6,000 words or more.

Looks like an FDR hit piece. FDR did keep the U.S. out of the war, for over two years, until it was attacked by the Japanese Empire. Even then, it wasn’t Roosevelt that declared war on Germany, even though he most likely could have. It was Hitler that inexplicably did it. So all this verbiage, “ruining” Amb. Kennedy’s political career, conspiring with Churchill, clandestine meetings, founding of the OSS, “secret” correspondence, etc., is all meant to put FDR in a bad light when he actually did exactly as he said he would do during his campaign, not send American boys into the fight. It’s when the fight came to America that there was no choice. Better to be prepared than do nothing. Thank God FDR and Congress were preparing the nation for war with their defense spending bills and their help for Germany and Japan’s victims. It wasn’t FDR that was inching America closer to war. It was the Axis. In hindsight, war with the two WAS inevitable and most likely FDR and Congress realized that but didn’t say so in public for obvious reasons. Their efforts pre America’s entry most likely saved countless lives.

This article correctly notes that the main concern at the time was Germany and Hitler’s ambitions. A bit more attention to the Japanese situation and possible consequences might have avoided some of the worst of the opening operations at Pearl Harbor, Singapore and the Philippines.

Always glad to see more on POTUS’ preparation for war with Germany & Japan. Thank you.