By Henrik Lunde

The Situation in the East, Summer 1944

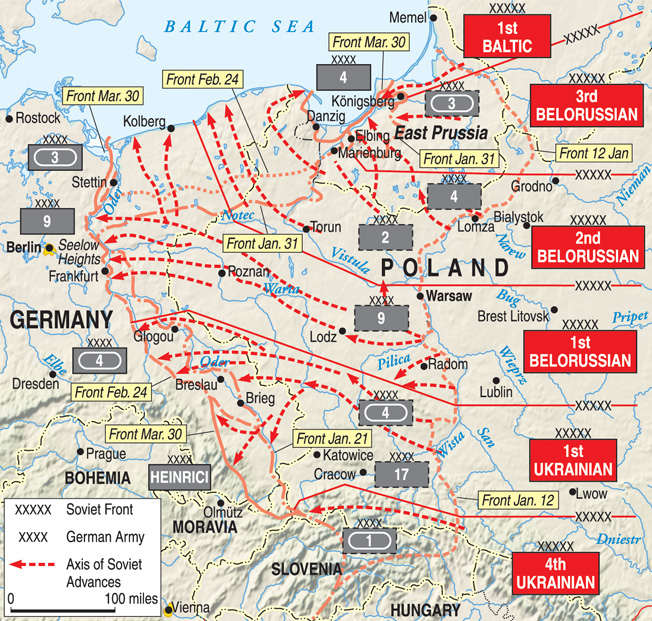

The area between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathian Mountains had been relatively quiet since the end of Operation Bagration late in the summer of 1944. In early January 1945 we find the Soviet armies positioned along the Vistula River to its great bend and then north along the Narew River. Stalin’s armies held several bridgeheads across each––at Serock and Rozan on the Narew and at Pulawy, Magnuszev, and Baranow on the Vistula.

The Soviets had an extremely impressive array of forces confronting the Germans. The 2nd and 3rd Belorussian Fronts (Army Groups) in the north, with 12 armies, faced Army Group Center’s three armies. Their superiority was even more ominous on the 1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian Fronts opposite Army Group A. There the Soviets had 2,200,000 troops, 6,400 tanks and self-propelled assault guns, and 46,000 indirect-fire weapons. Against these two fronts Army Group A’s Seventeenth, 4th Panzer, and Ninth Armies could muster “only” 400,000 troops, 1,150 tanks, and 4,100 indirect-fire weapons.

Operation Bagration, the Soviets’ 1944 summer offensive, had suffered logistically in its closing days, but they intended to avoid a similar situation in their next offensive. By January they had completed the most massive logistical buildup of the war. The two fronts––1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian––received 132,000 carloads of supplies. That was more than received by all four fronts before Bagration. Nine million rounds were made available to the two fronts as an initial issue along with 30 million gallons of gasoline and diesel fuel.

In December 1944, the Eastern Intelligence Branch of OKH (German Army High Command) issued a worrying estimate of Soviet intentions and capabilities. It concluded that the main Soviet effort would be delivered against Army Group A by the 1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian Fronts. In an important revision in January 1945, the OKH concluded that the expected offensive against Army Group Center had the lower Vistula area as its objective, while the drive against Army Group A could go as far as Berlin. The OKH expected the offensive to begin in the middle of January.

General Heinz Guderian, the OKH chief of staff, was very uneasy about the situation in the east. He visited Hitler at the Adlerhorst (temporary Führer headquarters in the Taunus Mountains) on Christmas Eve 1944 to plead for a change in strategy. Guderian wanted Hitler to call off the Ardennes offensive and move all forces that could be spared to the Eastern Front.

Guderian’s pleas were in vain. Hitler called the estimated buildup of Soviet forces in the east “a gigantic bluff” and refused to cancel Operation Wacht-am-Rhein––the planned thrust in the west. He also refused to bring units in from Norway or from the Courland pocket.

Guderian had good reasons to feel gloomy. He was particularly concerned about Army Group A, commanded by General Joseph Harpe. Since the transfer of the Ninth Army to this group in November 1944, it occupied a long front––from the northern border of Hungary to the confluence of the Vistula and Narew. This long front was defended, from south to north, by Group Heinrici (two armies) and the Seventeenth, 4th Panzer, and the Ninth Armies. It was a thinly held front, amounting to little more than a string of strongpoints with hardly any depth.

Guderian visited the Eastern Front in early January. Army Group A’s briefing in Krakow on January 8 was pessimistic––but realistic. It expected the Soviets to cover the distance from the Vistula to Silesia in six days. Guderian tentatively approved a plan involving an adjustment of the front around the Baranow bridgehead that would have shortened the line and made units available as reserves.

Army Group Center, under General Georg-Hans Reinhardt, was responsible for covering the approaches to East Prussia and Danzig. At the beginning of December 1944, this army group was in better shape than all others. Its three armies—3rd Panzer, 4th, and 2nd—had 33 infantry divisions and 12 panzer or Panzergrenadier divisions to defend a 575-kilometer front. But this situation changed radically by the end of the year. Five panzer divisions and two cavalry brigades had been stripped away for transfer to other fronts, and another panzer division was taken away in early January.

Reinhardt proposed to Guderian that Army Group Center be allowed to withdraw from its exposed position on the Narew to the East Prussian border. This would have significantly shortened its

front and made reserves available. Although Guderian agreed, he could not make such a major change without Hitler’s approval. And Hitler almost never approved withdrawals.

An apprehensive Guderian reported to Hitler back at the Adlerhorst on January 9. His main purposes were to seek approval for the proposal made by Army Group Center to withdraw and to argue for reinforcements from the west to go to Army Groups A and Center rather than to Hungary to protect the oil fields. Hitler refused all of Guderian’s requests and recommendations, including the adjustment Guderian had approved for Army Group A.

Soviet Plans

While Guderian and OKH were deeply worried about the future, the Soviets were full of confidence and optimism. The plans of Soviet High Command (STAVKA) amounted to a quick operation to end the war. It was a two-phase plan. The first phase, expected to last 15 days, involved a drive to the Oder and lower Vistula. The main drive would be executed by the 1st Belorussian Front, under Marshal Georgi K. Zhukov, and the 1st Ukrainian Front, under Marshal Ivan S. Konev, out of their bridgeheads on the Vistula.

Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front was to break out of the Baranow bridgehead and head west to Radomsko. Its right flank units were to assist Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front in destroying the Germans in the area between Radom and Kielce. The drive would continue to Krakow and the industrial region of Upper Silesia before ending along the Oder River.

The 1st Belorussian Front was to break out of the Pulawy and Magnuszev bridgeheads. The front’s right flank would encircle Warsaw while the main force would continue toward the city of Lodz in the south and Kutno west of Warsaw on the road to Poznan. The drive was to continue via Poznan to the Oder in the vicinity of Kuestrin and Frankfurt-an-der-Oder.

The 2nd Belorussian Front, under General Konstantin Rokossovsky, was to break out of the Serock and Rozan bridgeheads on the Narew north of the Vistula bend. Its mission was to drive northwest to the Baltic and clear the lower Vistula area.

At the same time, General Ivan Chernyakhovsky’s 3rd Belorussian Front was to drive west from its positions east of the Masurian Lakes toward Königsberg. It was hoped that it would be able to encircle the Fourth German Army in the lake area.

The Soviet plan did not call for a pause along the Oder. They expected that the German defenses would have crumbled and their armies shattered in the initial phase. The 1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian Fronts were to continue the drive to Berlin and then to the Elbe River (possibly even the Rhine). This part of the operation was expected to take about 30 days.

The State of the Wehrmacht

Some observers have pointed out that things looked better for the Germans at the beginning of 1945 than they had in September 1944. The Soviets had not made any substantial gains north of the Carpathians. Army Group South had almost regained its balance after being virtually destroyed in August 1944. The Germans were close to completing their withdrawals from Greece and Albania, and the Western Allies were stopped at the Gothic Line in Italy. The Ardennes offensive had not succeeded in its strategic objective, but it had upset the Allied schedule and delayed their advance into the heart of Germany.

These improvements, however, were illusions. The German ability to hold its fronts had been on a downward spiral, and in the next few months that spiral would spin out of control. The first element in this spiral was the lack of trained manpower to keep the space/force ratio from worsening.

By October 1944 German strength on the Eastern Front had fallen to less than 1,800,000 men; about 150,000 of these were Russian auxiliaries. This was a drop in strength of about 400,000 since June 1944.

The replacements arriving in the period from September 1 to December 31, 1944, went primarily to create new units. This resulted in an illusory increase in units but a glaring discrepancy between authorized strength and present for duty strength in existing formations. The Germans “fixed” part of this problem by simply reducing the 1944 table of organization by 700,000 spaces. The fact that a cumulative shortfall of 800,000 unfilled spaces still existed after the change to the table of organization is a telling illustration of the manpower problem.

This self-delusion was carried to great lengths. Artillery units of brigade size were designated “corps,” and groupings of one or two battalions of armor and infantry were designated “brigades.”

In the months following Operation Bagration, a number of unorthodox measures were taken to cope with the falling strength. Nazi Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels was ordered to come up with a million men through the Nazi Party machinery. By the end of the year he had achieved 50 percent of that goal through new recruits and inter-service transfers. In October 1944 Hitler activated the home guard (Volkssturm), composed of men between ages 16 and 60 who were otherwise exempt from the draft. About 200,000 men from military schools and training centers were organized into Gneisenau and Blücher battle groups.

The number of replacements between August and December 1944 was slightly larger (1,569,000) than the losses sustained by the Army (1,457,000) for the period June-November. What these units had in common was poor training, poor leadership, and inadequate numbers.

The Germans were also suffering in the matériel field. Although production of fighter aircraft, tanks, and assault guns reached new heights in late 1944, that output could not be sustained because of the heavy bombing of the Ruhr. What was even more alarming was the fact that the Western Allies were closing in on the Ruhr, and the Soviets would soon overrun Upper Silesia, where many production plants had been moved to avoid the strategic bombing.

The most glaring deficiency was in oil where there had been a catastrophic decline. Despite great efforts to develop more synthetic oil facilities, output had fallen. The Romanian and Latvian oil fields were lost and the hold on the Hungarian fields was tenuous.

Hitler continued his insistence on not making withdrawals and holding so-called fortified places bypassed by the Soviets. Although holding some communications centers made military sense because they complicated Soviet supply operations, tens of thousands of troops were sacrificed in trying to hold places that had little tactical or strategic significance.

During the offensive, Army Group North and Army Group Center were isolated––one in Courland and the other in East Prussia. Though some units were evacuated, those that remained encircled represented a terrible waste of manpower at a time when those hundreds of thousands of troops were needed farther west.

Army Group and Army headquarters had become little more than mechanical instruments for transmitting the Führer’s will. This alarming tendency had begun much earlier and represented a great change from 1939-1940.

German leaders were taught to expect the unexpected on the battlefield and instructed to deviate from plans in order to achieve their goals. Leaders were expected to make quick decisions and equally quick executions. It was a cornerstone of German military doctrine. Part of that doctrine was that higher German echelons kept their intervention in operations of subordinate units to a minimum. These principles go far back in Prussian history and are referred as Auftragstaktik (task tactics) and Selbständigkeit der Unterführer (independence of subordinates). They were immortalized by Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz’s reply when Frederick the Great repeatedly attempted to get Seydlitz and his cavalry to attack the unbroken Russian infantry line at the Battle of Zorndorf in 1758: “Tell His Majesty that my head will be at his disposal after the battle, but that as long as the battle lasts I intend to use it in his service.” There are examples from the early part of World War II illustrating that this concept was alive and well.

This had all changed by 1942-1943, and historian Robert M. Citino argues persuasively that new communications technologies, a key to mobile operations, contributed to the demise of the earlier doctrine. Improved communications allowed higher commanders—especially Hitler, who distrusted his generals—to intervene in operational matters. This tendency reached ridiculous levels in January 1945. Incensed at the withdrawal from Warsaw, Hitler, in order to maintain absolute control over decisions at the front, ordered special radio teams stationed at Army and Corps headquarters. The commanders were responsible for reporting all important events through this new radio channel and for making situation reports four times a day of all the facts that might be necessary for decision making by the highest leadership.

The constant shifting or relief of commanders that had reached a point of disruption during Operation Bagration continued at an accelerated pace in 1945. The quality of senior commanders also deteriorated as loyalty to Hitler became the only real prerequisite. Two loyal disciplinarians––Generals Ferdinand Schroeder and Lothar Rendulic––are typical examples. Hitler’s quest for loyalty reached a ludicrous level when he appointed the amateur Heinrich Himmler to command Army Group Vistula.

Soviet Breakthroughs

On January 12, 1945, the Eastern Front exploded from the Carpathians to the Baltic as Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front, with nine armies at its disposal, launched its offensive out of the Baranow bridgehead, followed a few days later by the other fronts to its right. The Germans were caught by surprise. The weather was overcast and foggy, and the Germans had expected the Soviets to wait for better weather so they could fully utilize their immense air superiority.

The German frontline positions were quickly overwhelmed. By noon on the first day, the Soviet infantry had opened gaps that allowed tank forces to pass through. The 48th German Panzer Corps’ divisions were destroyed. The reserve corps––24th Panzer––was ordered to counterattack, but its two divisions near the Baranow bridgehead were decimated before they could get out of their assembly areas.

The 4th Soviet Tank Army turned north on January 13 while the 52nd and 3rd Guards Tank Armies pushed directly west. Before nightfall Soviet spearheads had reached the Nida River, where a 70-kilometer gap provided a clear route to Upper Silesia and the Oder. The remnants of the 24th Panzer Corps went into positions around Kielce.

Because the Soviet offensive was staggered, General Smilo von Lüttwitz’s Ninth Army on Army Group A’s left flank had two days’ warning when the 1st Belorussian Front attacked from the Pulawy and Magnuszev bridgeheads on January 14. This advance notification did not help much. Both frontline corps were badly cut up and lost half their strength before the day was over.

On January 15, the right flank of the 1st Belorussian Front, the 47th Army, broke through the German lines north of Warsaw on the boundary between Army Groups A and Center. On the same day, three armies from the 1st Ukrainian Front drove the 24th Panzer Corps out of Kielce.

The 3rd Belorussian Front under Chernyakhovsky opened the offensive against Army Group Center on January 13 with an attack on the 3rd Panzer Army north of Gumbinnen. This was followed on January 14 with an attack by the 2nd Belorussian Front under Rokossovsky out of the bridgeheads at Serock and Rozan against the Second German Army. Both the 3rd Panzer and Second Army withstood the Russian onslaught for two days and sealed all penetrations. It was not the Soviets who changed this promising beginning for Army Group Center, but Hitler. As Rokossovsky was attacking out of his bridgeheads on the Narew, Hitler ordered Panzer Corps Grossdeutschland and its two panzer divisions in Army Group Center transferred to Army Group A.

The weather was characterized by an icy fog, and this had prevented the Soviets from fully exploiting their massive tank and air superiorities. The weather began clearing in the north on January 15, and the 3rd Panzer Division was forced back to keep its front from falling apart. The weather also cleared in the Second Army area on January 16, and the main force of the 2nd Belorussian Front––five armies and an assortment of tank and mechanized corps––broke through from the Rozan bridgehead and headed northwestward for the mouth of the Vistula.

Since Chernyakhovsky’s 3rd Belorussian Front had failed to make a substantial breakthrough against the 3rd Panzer Army, it switched its main forces northward opposite the Fourth German Army for another try. In view of what was happening in the Army Group A and Second Army areas, this was the time to pull the Fourth Army and the 3rd Panzer Army back from their exposed positions. Such a withdrawal would prevent encirclement, shorten the front, and provide reserves. General Reinhardt proposed such a withdrawal on January 16 but Hitler refused. The most he was willing to do was to transfer two divisions from the Fourth Army to shore up the Second Army against Rokossovsky’s drive. As usual, this compromise Band-Aid solution left things worse than they were. The Fourth Army was weakened and left in its positions, an invitation to encirclement. The two added divisions made practically no difference for the Second Army.

German Leadership Chaos

Belatedly, on January 13 Hitler ordered two infantry divisions transferred to the Eastern Front from the west. The following day, before anyone had a firm idea of how the offensive would develop, he ordered Panzer Corps Grossdeutschland and its two divisions transferred from Army Group Center to Army Group A. The next day he also ordered Army Group South to send two panzer divisions to Army Group A.

Although some have credited Guderian with convincing Hitler to take these steps, they appear to have been made by Hitler on his own volition, particularly the transfer of Panzer Corps Grossdeutschland. Guderian had argued (on January 14 and 15) that the Eastern Front would succumb without sizable and timely reinforcements from the west and a halt to Army Group South’s offensive so that its armored divisions could be provided to Army Group A. However, Hitler refused to provide additional divisions from the west or stop Army Group South’s offensive.

With the Ardennes offensive at an end, Hitler moved his headquarters from the Adlerhorst to Berlin on the evening of January 15. In his absence the OKH issued a directive allowing Army Group A some operational latitude in the area of the Vistula bend, including permission to evacuate Warsaw. Hitler became incensed when he discovered that it was too late to countermand the directive, as it was already being executed. He had the three senior officers of the OKH’s Operations Branch arrested and relieved General Harpe, the group commander. General Ferdinand Schörner was appointed to take Harpe’s job.

What followed was a dizzying shifting of commanders. General Rendulic was brought down from Norway to replace Schörner as commander of Army Group North. Rendulic’s appointment was short-lived. Army Group North was renamed Army Group Courland on January 26, and the following day––after 12 days in command––Rendulic was sent to command the new Army Group North (formerly Army Group Center). General Heinrich von Vietinghoff assumed command of Army Group Courland on January 27, but on March 10 he was sent to command in Italy and Rendulic again assumed command of Army Group Courland. These officers hardly had time to unpack, much less become familiar with their commands.

Upon his arrival in Berlin in the evening of January 15, Hitler told Guderian, to the latter’s dismay, that he was moving the 6th SS Panzer Army’s two corps from the Western Front to Army Group South instead of to A or Center. Army Group South was the same organization that had just been ordered to provide two panzer divisions to Army Group A.

Soviet Pursuit

By January 17 the Soviets were into the pursuit phase of their offensive nearly everywhere. The 24th Panzer Corps, caught between Konev and Zhukov’s drives, was thrown back to the Pilica River. Konev’s spearheads crossed that river and moved against Radomsko and Czestochowa. STAVKA ordered both Zhukov and Konev to accelerate their drive to the Oder, and Konev to use his second echelon to take Krakow and the Upper Silesia industrial area.

In the German camp, one of the first acts of the energetic but sometimes brutal General Schörner (his nickname was Schörner the Bloody) was to relieve the commander of the Ninth Army, General von Lüttwitz. It can be safely assumed that the relief was carried out at Hitler’s bidding, as he was fuming at the failure of the Ninth Army to hold Warsaw. General Theodor Busse was appointed to command the Ninth.

Schörner also began to send optimistic reports to Hitler. He said that he would be able to defend Upper Silesia when he received the two promised panzer divisions from Army Group South. He gave the Seventeenth Army the mission of defending Silesia. He further assured the Führer that the Soviet drive toward Poznan in the gap between the 4th Panzer Army and the Ninth Army could also be stopped with generation of new forces. He did not explain where these forces would come from.

The dispositions and orders Schörner gave to the 4th Panzer and Ninth Armies reveal that either he was engaged in wishful thinking or that he did not fully grasp the situation in his new command. He ordered the 4th Panzer Army to stop the Soviet drive toward Breslau at a point west of Czestochowa. The Soviets were already in Czestochowa and the 4th Panzer lacked the forces to carry out the mission because the 24th Panzer Corps had become separated from the army’s left flank. The army was in fact reduced to the remnants of two divisions and a couple of brigades. Schörner also ordered the Ninth Army to hold between Lodz and the Vistula and to launch a counterattack to the south. The objective was to close the gap between the Ninth Army and the 4th Panzer Army.

The Soviet pursuit was so overwhelming and swift that all plans were overcome by events. Both Zhukov and Konev’s tank columns were advancing at a rate of 40-50 kilometers a day and the infantry at 30 kilometers a day. Zhukov’s forces bypassed Lodz and headed for Poznan. Konev’s forces were heading to Breslau, throwing the 4th Panzer Army back to the German border, while some of his infantry armies turned south to Upper Silesia. The Ninth Army (40th Panzer Corps and Panzer Corps Grossdeutschland) was trying to hold a line south of Lodz long enough for the 24th Panzer Corps to cross the Pilica River. Contact between Panzer Corps Grossdeutschland and the 24th Panzer Corps was established along the Warta River on January 22. However, they were both driven westward in the relentless tide of the Soviet offensive.

Along with them on the roads was a mass of refugees fleeing in terror from the Soviets who were beginning to exact revenge on civilians. The slaughter of civilians on the Eastern Front by both sides was on a scale that has no equal in modern history.

A wide gap had developed between the Seventeenth German Army screening the industrial region of Upper Silesia and the 14th Panzer Army, which had been driven back to the Oder. The 3rd Guards Tank Army had reached Namslau in Silesia. Konev turned this army south on January 21 along the Oder River behind the left flank of the 17th Army. His armies closed on the Oder along a 225-mile stretch between Cosel and Glogau between January 21 and 24. The Soviets crossed the river in several places while the 4th Panzer Army was left holding bridgeheads on its east bank on both sides of Breslau. Schörner’s orders for the 4th Panzer Army to counterattack the Soviet bridgeheads on the west bank could not be executed.

The 3rd Guards Tank Army of the 1st Ukrainian Front coming into Silesia from the northwest appears to have deliberately left an escape route open at the southern end of the Silesian pocket. If so, it was probably a sanctioned action to avoid heavy fighting that would have destroyed much of the industrial region. The 17th German Army withdrew through this opening between January 28 and 30.

On January 23 the Germans created a new army group in the north, designated Army Group Vistula. This was considered necessary to fill the gap that had developed between Army Group Center and Army Group A, brought about by the 1st Belorussian Front bypassing Poznan on January 25 and heading directly for the Oder as the 2nd Belorussian Front turned north along the lower Vistula. Guderian had argued for bringing in General Maximilian von Weichs from Army Group F in the Balkans to take over Army Group Vistula but Hitler gave the command to Heinrich Himmler, who had never before so much as commanded a squad in combat. Hitler ordered Himmler to close the gap between the two army groups––A and Center––to cover Danzig and Poznan, and to maintain a corridor to East Prussia.

Some of the tasks given Army Group Vistula were already swamped by events. Poznan was bypassed. The Soviets were about to reach the Baltic at the mouth of the Vistula, thereby isolating Army Group Center in East Prussia and severing the corridor that Hitler wanted kept open.

For no apparent reason, the Germans resorted to a massive redesignation and reshuffling of units on January 26 and 27. Army Group North was designated Army Group Courland, while Army Group Center became Army Group North. Army Group A became Army Group Center. The new Army Group Center lost the Ninth Army to Army Group Vistula. Himmler thus ended up commanding a front with many bends and twists from the mouth of the Vistula in the north to Glogau on the Oder where it tied into the new Army Group Center.

To defend this long front, Army Group Vistula had an assortment of units, many of them untried. It had two SS divisions, one Latvian SS Division, Volkssturm units, and remnants of the Ninth Army. Two major units of the Ninth Army––the 24th Panzer Corps and Panzer Corps Grossdeutschland––were now part of the new Army Group Center. Two divisions were encircled in Torun, and a similar-size force was encircled at Poznan. It made sense to try to hold Poznan, as it was the major transportation hub east of the Oder.

There was a blizzard in central Europe on January 27 and 28, followed by a warm spell that melted the snow and turned the ground into mud, hindering Soviet operations. Zhukov, having covered nearly 500 kilometers, was beginning to worry about his northern flank. Schörner was feverishly trying to build a front along the Oder, and Army Group Vistula’s sector showed more cohesion. With the shrinking front, the space/force ratio began favoring the Germans.

The 1st Belorussian Front reached the Oder north of Kuestrin on January 31, and by February 3 it had closed up to the river from Zehden south of Stettin to its left boundary. Though the Germans still held bridgeheads east of the river, the Soviets held bridgeheads north of Kuestrin and south of Frankfurt-an-der-Oder.

The Germans were bringing in a motley assortment of reinforcements to shore up the fronts in Pomerania, in West Prussia, and along the Oder. These included the so-called Gneisenau and Blücher battle groups, Volkssturm units, and Navy and Luftwaffe personnel organized into infantry units. After adamantly refusing to withdraw the troops in Courland and East Prussia before they were surrounded, Hitler now allowed some of these units to be brought out by air and sea. On January 17 he ordered one panzer and two infantry divisions out of Courland. A further two-division drawdown was ordered on January 22. These five divisions joined Army Group Vistula.

In less than three weeks the Soviets had completed one of the most spectacular advances of the war, almost 500 kilometers. At Kuestrin, Zhukov’s front was only 65 kilometers from Berlin, and there were no obvious reasons for not carrying out the second phase of the offensive––seizing Berlin and moving to the Elbe. The daily Soviet losses in the offensive were about 20 percent less than in Operation Bagration. The front commanders––Zhukov and Konev––reported to Stalin on January 26 that they would be ready to continue to Berlin after a stop of three to six days to replenish supplies and reorganize.

Stalin introduced a note of caution. He was concerned about the thinly held northern flank of the 1st and 2nd Belorussian Fronts. He told Zhukov to wait until the 2nd Belorussian Front had come farther west––10 to 14 days––and ordered Zhukov to shift the weight of his front northward and expand the bridgeheads near Kuestrin. STAVKA, in order to relieve Rokossovsky of responsibility for flank security, transferred the three right-flank armies of the 2nd Belorussian Front to the 3rd Belorussian Front. To compensate for this loss, Rokossovsky was given a fresh army from the strategic reserve. His mission was to capture West Prussia and Pomerania up to the mouth of the Oder at Stettin. Konev was to keep moving toward the Neisse and Dresden.

The confluence of the Oder and Neisse Rivers is located north of Guben. The Oder River flows northwest up to that point, whereas the Neisse flows north. There was, therefore, a considerable expanse of land between the two rivers. The directive telling Konev to press on to Dresden also gave him an opportunity to shorten the distance to Berlin by occupying the territory between the two rivers.

The 1st Ukrainian Front attacked out of the Steinau bridgehead on the upper Oder on February 8 with five armies, two of them tank armies. General Schörner also had to worry about the bridgehead between Ohlau and Brieg, south of Breslau, where Konev had two armies and two tank corps ready to attack. These drives by Konev also threatened Army Group Center’s lateral lines of communication. Schörner was given two additional divisions to cope with the threat.

The 3rd Guards Tank Army smashed through the 4th Panzer Army on the first day of attack from the Steinau bridgehead. By evening of the first day its spearheads were at the outskirts of Liegnitz and began turning south to encircle Breslau. Other elements continued west to the Bober River south of Bunzlau. To the north the 4th Tank Army crushed Panzer Corps Grossdeutschland and encircled Glogau; Breslau was encircled on February 12 after three days of heavy fighting. The main thrust continued across the Queiss and Bober Rivers north of Sagan.

The southward turn of the 3rd Guards Tank Army gave the 4th Panzer Army a respite and it counterattacked, cutting behind the 4th Tank Army, which was headed toward the Neisse River. The 3rd Guards Tank Army had meanwhile turned west toward Goerlitz. Schörner attacked its southern flank with one panzer division but failed to slow its advance. By February 21 Konev had five of his armies along the Neisse from its confluence with the Oder to Goerlitz. Crossing the Neisse against the six divisions of the 4th Panzer Army should not have been a difficult task for Konev but he nevertheless called a halt to operations.

German intelligence soon began picking up signs that the Soviets were ready to restart their offensive. In the last week of February, OKH warned the army groups that the next Soviet main effort would be on the Oder-Neisse between the right flank of Army Group Vistula and Goerlitz with a secondary drive into Pomerania.

Change in Soviet Strategy

German assumptions as to probable Soviet actions, though logical, were proved wrong. They could not bring themselves to believe that the Soviets would be deflected from their ultimate objective by illusory threats to their flanks, but this appears to be what happened. The first signs of a change in Soviet intentions began to be picked up by the Germans between the 24th and 26th of February. In fact, the 3rd Belorussian, 2nd Belorussian, and major portions of the 1st Bellorussian Fronts attacked northward from Königsberg in the east to Stettin in the west.

The fighting in East Prussia had been going on since early February. By the third week of February, the 3rd Belorussian Front had pushed the Fourth Army into a 35-mile-wide and 15-mile deep beachhead along the Baltic. The front commander, Chernyakhovsky, was killed in the fighting, and Marshal Aleksandr Vasilevsky took command of the front. The 1st Baltic Front had forced the remnants of the Army Detachment (Armeeabteilung) Samland into the Samland Peninsula. Königsberg was isolated. On February 20, two days before the Soviets had planned their own attack on the forces in the Samland Peninsula, the Germans on the peninsula launched a counterattack that caught the Soviets by surprise and carried the Germans all the way to Königsberg.

General Guderian had planned a counterstroke against Zhukov since the end of January. It was supposed to be a two-pronged offensive with one drive from Stargard in East Pomerania and another from the Oder bend near Guben. Guderian argued that the 6th SS Panzer Army, commanded by SS General Josef (Sepp) Dietrich, consisting of five panzer divisions, should form the southern prong. Hitler refused to divert this army from its scheduled move to Hungary.

Hitler’s decision reduced the offensive to a southward attack from the Stargard area behind the Oder front. Guderian planned to attack on a 50-kilometer-wide front and demanded speed for a deep thrust. In what can only be described as a remarkable feat at this point of the war, Guderian managed to scrape together from other sectors of the Eastern Front, and from the west, two corps headquarters and 10 divisions, seven of those panzer divisions.

Problems plagued the operation from the start. Guderian did not want any of the divisions employed prematurely, but Himmler had difficulties holding the staging area and eventually was forced to commit several of the new divisions. Guderian wanted an early date for the counterattack but Himmler dragged his feet. It came to a showdown with Hitler on February 13, at which Guderian demanded that the deputy chief of staff of the Army, General Walter Wenck, receive a special mandate to command the offensive.

In another compromise decision, Hitler agreed to Guderian’s proposal for Wenck to command the operation under Himmler but the specific responsibilities of each were not spelled out. After a quick inspection trip, Wenck discovered that most of the forces for the counterattack were not ready and decided to launch the offensive piecemeal, starting with a one-division attack against Arnswalde, where a small, encircled German garrison was located.

The attack was launched on February 15. Catching the Soviets by surprise, the Germans captured the town by early afternoon. This initial success persuaded Himmler to commence the whole operation on February 16. That day, however, was wasted in probing attacks, and the offensive was irretrievably stuck before it got started, and Wenck was severely injured in an automobile accident on his way to brief Hitler. The German tanks were confined to roads because of the rain and mud. The badly executed operation came to an end on February 18.

Though the Stargard operation hardly caused any damage to the Soviets, it may have brought the Germans an unexpected dividend with profound consequences for their immediate postwar future. A mood of caution seemed to have taken hold of STAVKA as it began dismantling the preparations for the continued advance on Berlin and the Elbe. Instead of a westward drive, the Soviets became involved in time-consuming clearing operations in Pomerania and Silesia.

On February 17 STAVKA ordered Zhukov to send major portions of his front to the north to assist the 2nd Belorussian flank to clean out East Pomerania. Some writers have credited the fiasco-ridden Stargard attack, the Samland attack, and the German attack against the Hron bridgehead in Hungary with changing Soviet strategy. The timeline is not convincing. The Stargard attack did not start until February 15, that in Samland on February 20, and the attack at Hron on February 17.

At the beginning of the Vistula offensive on January 12 the Soviets had good reason to be in a hurry. Because Hitler had canceled the Ardennes offensive on January 3, the Soviets may have expected that the Western Allies would resume a rapid drive into the heart of Germany. However, the Allies spent January and February recapturing lost ground and in heavy fighting west of the Rhine. Consequently, the Soviets may have concluded that there was no longer a reason to hurry.

However, the continued strength displayed by the German Army may have played a role. Despite suffering about 660,000 casualties in January and February, the German strength on the Eastern Front––about 2 million––was in fact slightly higher than at the start of the offensive, though 556,000 of these were bottled up in Courland and East Prussia. The quality of the troops is an entirely different matter. Despite losses estimated at 680,000 in January––less than other recent major offensives––the Soviet forces were in good shape for continuing their offensive.

The thaw had caused problems for the Soviets, as had German possession of several communications centers in their rear, particularly Poznan and Breslau. These were road and railroad hubs, and as long as they were in German hands they severely hampered Soviet logistic flows. Poznan held out until February 23 and Breslau for 82 days, until May 6.

The space/force ratio was also working against the Soviets. The maneuver room for their armies became restricted as they moved west against ever-shrinking German fronts. The Germans benefited from the shortened fronts––about 300 kilometers from the Baltic to the Bohemian mountains. They were able to increase the density of troops along the fronts and in some places prepare defenses in depth with reserves, a luxury they had not enjoyed since the fortunes of war turned against them. All these factors undoubtedly played into the STAVKA decision on February 17 to abort the original second phase of their offensive and turn their attention to the flanks.

The operations in Pomerania ran their course during March. The 2nd Belorussian Front managed to split the Second German Army away from the 3rd Panzer Army by driving to the coast at Koslin. The 3rd Panzer Army was pushed behind the lower Oder near Stettin on March 19. The operations against the Second German Army took longer, but Rokossovsky eventually drove it into a narrow strip along the Bay of Danzig. Army Group North ended up holding a precarious strip from Köningsberg to the mouth of Vistula with the remnants of two corps holding beachheads at Gdynia and on the Hel Peninsula.

Resumption of the Soviet Westward Drive

The military situation on the Western Front changed radically in March. The Western Allies had closed to the Rhine and established beachheads on its west bank, Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group in early March at Remagen, and Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group about two weeks later. The drive to encircle the Ruhr was in full swing.

On March 31 Stalin received a message from Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower outlining his plans, which made no mention of Berlin. Stalin’s immediate answer casually mentioned that Berlin had lost its former strategic significance. He announced that the Soviet westward offensive would begin in the second half of May.

The Soviets began a very hasty redeployment for an offensive that had Berlin as its objective. Stalin immediately called Zhukov and Konev to Moscow after receiving Eisenhower’s message. He had become disturbed by the successes of the Western Allies and, concluding that the Allies were heading for Berlin, did not believe the truthfulness of Eisenhower’s message. (In fact, Eisenhower, with General George C. Marshall’s concurrence, had decided to let the Soviets take Berlin, on the correct assumption that urban warfare in the Nazi capital would cost horrendous casualties.)

Zhukov and Konev met with Stalin on the following day, April 1. Stalin explained the Eisenhower message and his conclusion that the British and Americans intended to take Berlin. Both front commanders were confident that they could take Berlin before the British and Americans, but the rivalry between the two commanders became obvious from the beginning. Stalin told them to remain in Moscow and present their plans for taking Berlin within 48 hours.

Zhukov and Konev presented their plans to Stalin on April 3. Zhukov’s forces were only 55 kilometers from Berlin and he intended to throw four field armies and two tank armies into the main assault, with other armies involved in supporting attacks. The total number of troops involved was more than 768,000 men when follow-on echelons were included. He planned to launch his attack during darkness and use 140 anti-aircraft searchlights to blind enemy gunners. The offensive would open with a barrage from a reported 11,000 guns and large-caliber mortars.

Konev, whose forces were 120 kilometers from Berlin at their nearest point, also presented an enormous plan, but it was more complicated. Konev had massed his tank armies on the right so they could immediately exploit a breakthrough by driving directly for Berlin. His plan called for an attack at dawn across the Neisse under the protection of a massive artillery and air preparation lasting 2 hours, 35 minutes and an immense smoke screen laid by low-flying aircraft. He intended to throw five field and two tank armies into the assault––a total of about 512,000 troops. Although Konev had five armies, he needed two more, and these were promised by Stalin.

Stalin approved both plans but gave Zhukov the mission of taking the German capital; Konev was to drive west past the southern outskirts of Berlin to link up with the Americans on the Elbe. This seemed to relegate Konev to a secondary role. At a second meeting on April 3, Stalin adjusted the line on the map that separated the two fronts, stopping at the town of Lübben, about 60 kilometers southeast of Berlin. Konev was happy. He counted on speed to reach Lübben quickly and felt confident that Stalin would then give him permission to swing north to Berlin. The date for the attack was set as April 16, a whole month earlier than the date Stalin had given Eisenhower.

Crossing the Oder/Neisse and the Seelow Heights Battle

After hard fighting, the Soviets managed to expand their bridgehead around Kuestrin in late March to where, despite German counterattacks, it was 50 kilometers long and about 15 kilometers deep. Kuestrin was to serve as the springboard for Zhukov’s drive to Berlin. After they had seized the Seelow Heights ahead and to the west of the bridgehead, the road to Berlin would be relatively open.

Also in late March there was a change in command in Army Group Vistula. Himmler, who had lost some favor with Hitler after the Stargard fiasco, gladly accepted Guderian’s suggestion that he “retire.” Guderian recommended General Gotthard Heinrici as Himmler’s replacement and Hitler accepted.

Heinrici was considered an expert on defensive operations in the German Army. Except for participating in the invasion of France in 1940, he spent the whole war on the Eastern Front. He did not have an ideological bent and was therefore not on good terms with the Nazi hierarchy. Heinrici believed in defense in depth, liberal use of firepower, and adequate reserves strategically placed. In the battle along the Oder, he had none. Other difficulties included the lack of fuel, which meant that reserves had to be closer to the battlefield than Heinrici would have wished. The multitudes of refugees on the road further complicated both the movement of reserves and resupply.

Guderian’s own days were numbered. There was an angry confrontation between Guderian, General Busse (commander of the Ninth Army), and Hitler on the day that the second counterattack against Kuestrin failed––March 27. Hitler placed Guderian on six weeks’ sick leave and made General Hans Krebs acting chief of staff, OKH. Krebs had been Field Marshal Busch’s and, later, Field Marshal Model’s chief of staff.

The key position of the battle along the Oder/Neisse was Seelow Heights, a slight rise facing Zhukov’s front. The terrain to the west of the Oder at Kuestrin is characterized by a horseshoe-shaped plateau known as the Seelow Heights, which ranges in elevation from 100 to 200 feet. It overlooks a marshy valley known as the Oder Bruch, from the streams running through it. It was here on this critical height that Heinrici had a chance to blunt the Soviet attackers as they advanced across the low-lying, marshy terrain in front of and below the heights exposed to the German guns. Heinrici assumed that Zhukov was aware of this and that he would go to special lengths to quickly seize the area.

The area on and around Seelow Heights was held by the 56th Panzer Corps under General Helmuth Weidling. Weidling had assumed command of the corps when he arrived on the night of April 12 and used it to block the Soviets on the main route to Berlin. The other two corps of General Busse’s Ninth Army were deployed on his flanks––the 101st on his left and the 11th SS on his right.

The 56th Panzer Corps was a panzer corps in name only. It consisted of the 9th Parachute Division, the 20th Panzergrenadier Division, and the “Muncheberg” Panzer Division. The 9th Parachute Division, on the corps’ left flank, was organized in its present form from various parachute-training units. The 20th Panzergrenadier Division had been seriously depleted over the past months. The “Muncheberg” Panzer Division had also been formed in February from a motley assortment of regular army elements, training units, SS, Volkssturm, and Hitler Youth components.

Heinrici’s two armies (3rd Panzer and Ninth) had fewer than 700 tanks and self-propelled assault guns. He faced the assault not only of Zhukov’s front but also Rokossvsky’s front in the north. Because of the small number of weapons and the severe lack of fuel, the tanks and assault guns were dispersed among the frontline units. The Germans were also totally outmatched in artillery. Against estimates that range upward to 20,000 indirect-fire weapons of all calibers that Zhukov and Konev each could muster, Heinrici is reported to have had 744, complemented by about 600 anti-aircraft guns used as artillery. Ammunition and fuel supplies were critically low, less than two and a half days’ basic load in the Army. Some of Heinrici’s units were down to a half dozen rounds per gun.

Heinrici knew that he could not stop the attack of the massive armies to his front––armies that had covered 1,100 kilometers and crossed numerous rivers in the past nine months against a German Army that had been in much better shape. The only thing he could do was delay the eventual outcome. All but the most fanatical Nazis and the delusional bunch in the Führer bunker knew that the war was lost.

Heinrici believed in detailed reconnaissance, and from these reports he concluded accurately that the attack would come on April 16. During the night of April 15-16, he ordered his troops on the Seelow Heights withdrawn from their front line. The heaviest artillery barrage of World War II––real shock and awe––marking the beginning of Zhukov’s offensive therefore fell on empty German positions. Although this was a good beginning, it was only a matter of time before the enemy would break through. The avalanche of explosives was so great that it caused an atmospheric disturbance. Survivors talked about a sudden hot wind that blew through the forests. The dull roar of the guns could be heard in the eastern suburbs of Berlin, and a warm breeze rattled blinds.

The troops of the 8th Guards Army under General Vasily I. Chuikov, defender of Stalingrad, began to move forward during the bombardment. As soon as they were within range they were greeted by very accurate fire from the Seelow Heights. Zhukov’s frontline commanders later complained bitterly that the 140 anti-aircraft searchlights, rather than blinding the enemy, illuminated the Soviet troops moving forward. It was not long before the advance was brought to a halt by German fire and the soft marshy ground that mired the tanks and assault guns.

Zhukov made some quick decisions. He ordered heavy air strikes and artillery fire against the Seelow Heights. In an apparent act of frustration, he also decided to commit his tank armies before the infantry had punched a hole through the German lines––a breach of standard practice for which he has been severely criticized. Zhukov’s infantry and armor became entangled in a paralyzed mass in front of the German main battle positions. Fortunately for the Soviets, the Germans did not have the forces to take advantage of this lucrative opportunity.

Zhukov’s exasperation may have been heightened by what was happening on Konev’s front. Konev was in a hurry. His front attacked at 150 sites along the Neisse River under the cover of a dense smoke screen and an artillery and air preparation (6,500 aircraft supported the two fronts) that lasted 2 hours, and 35 minutes. The main crossing site was in the area of Buchholz and Triebel. The attack hit Schörner’s Army Group Center at its boundary with the Ninth Army. The terrain on the west bank was steep and heavily fortified with concrete bunkers. Konev planned to throw in his armored divisions as soon as his troops had secured footholds on the western bank. Konev had his first bridgehead secured by 7:15 am, and one hour later his tanks and assault guns were engaging the enemy. By the end of the artillery preparation Konev’s troops were established on the west bank of the Neisse after securing 133 of the 150 crossing sites. Elements of two armies and two tank armies were across the river. In the Triebel area the Soviets had already punched through the German defenses. In eight hours Konev’s forces had opened a 30-kilometer gap in the German lines and were pouring through. By the end of the day Konev’s troops were only 30 kilometers from Lübben.

Konev planned to dash past Cottbus and head for Lübben, the place where Stalin’s boundary between the two fronts ended. If he reached Lübben quickly, he planned to ask Stalin for permission to immediately swing north to Berlin. He figured such permission would be granted, as it was in the evening of April 17.

With Konev’s breakthrough in the south, the immediate fate of Berlin was decided no matter how gallantly General Weidling’s men defended the Seelow Heights. Heinrici had used up all his reserves to support the Ninth Army. Two SS divisions––Nordland and Nederland––hampered by lack of fuel––started moving from the 3rd Panzer Army sector at midnight on April 17 toward the Ninth Army and Seelow Heights. SS Division Nordland (composed mostly of Norwegian and Danish volunteers) was assigned to the 56th Panzer Corps. They arrived in driblets and too late to affect the outcome of the battle, which was already lost.

The fighting on Seelow Heights had ended by April 19. It had been a costly affair for the Soviets. They admitted to 33,000 killed and the loss of 743 tanks and self-propelled assault guns; the Germans lost 12,000 men. But the road to the German capital was now open from both the south and east, and virtually nothing barred the Soviet advance on the German capital. The endgame in Europe was about to begin.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments