By Michael E. Haskew

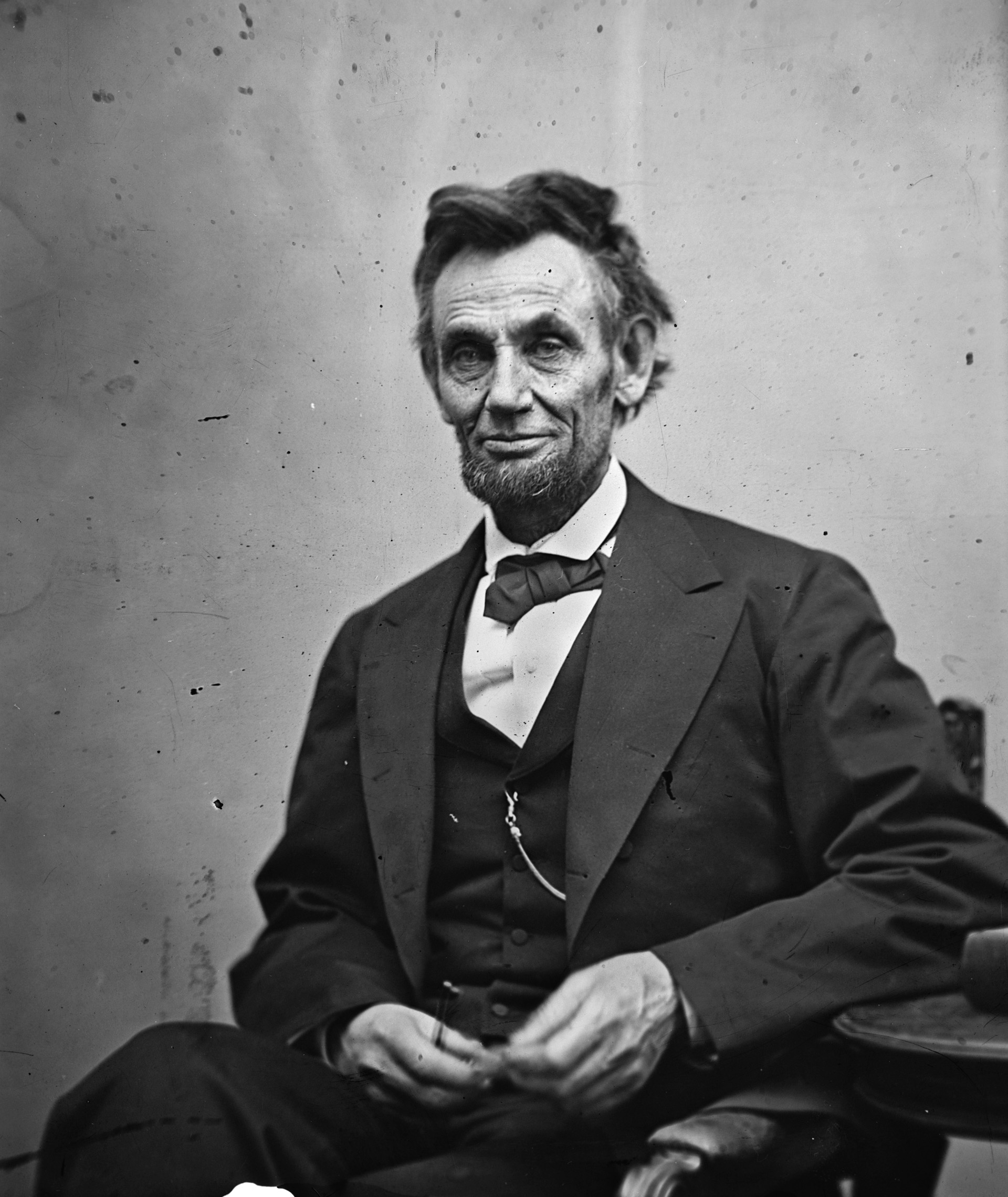

On February 5, 1865, four days before his 56th birthday, President Abraham Lincoln sat for a series of photographs in the studio of Alexander Gardner at 511 Seventh Street, N.W., in Washington, D.C. Lincoln was accompanied by portrait artist Matthew Wilson, who had been commissioned to paint the likeness of the president. Since Lincoln had more pressing business to attend to and Wilson needed his subject to pose for a lengthy period of time, it was agreed that photographs would be made for the artist to use in his work.

Although Gardner’s purpose that day was not to preserve an enduring likeness of Lincoln, his series nevertheless has proved immensely more memorable than Wilson’s subsequent finished portrait. Reproduced countless times, the most recognized image of Lincoln is from the final exposure of the sitting. Gardner reportedly made only one print of it, from a cracked negative that he quickly discarded. Nevertheless, Lincoln’s weary and weathered face reflects the somber mood of a nation nearing the end of four years of bloody civil war. The poignant image of the prematurely aging Lincoln, with furrowed brow and deeply etched crevices and wrinkles, reaches across time and touches the heart more profoundly than volumes of written words. Such was the emerging power of photography, which brought the Civil War into the homes of horrified, fascinated civilians in a way that never before had been seen.

The Advent of Photography

By the 1860s, photography itself was little more than 30 years old. Photographic techniques had progressed somewhat in three decades, but the process was still lengthy and the equipment was cumbersome. One of the most popular methods of outdoor photography, and the technique used by virtually all Civil War photographers, was known as the wet-plate process, which produced a plate-glass negative that could be printed on paper. First, a glass plate was coated with a flammable mixture called collodion, consisting of a number of chemicals, including pyroxylin, ether and alcohol, to sensitize the plate to light. Then the plate was coated with silver nitrate, placed in a container impervious to light, and fitted inside the camera. The photographer then removed the cap on the lens for a period of a few seconds to expose the plate to light.

The exposed plate remained in the container as the photographer carried it to his darkroom for development in a wash of pyrogallic acid before a solution of sodium thiosulfate fixed the image to guard against fading. The plate was then washed with water, dried and coated with varnish. Adequate light was critical to the wet-plate process, and the slightest movement blurred the image. Therefore, human subjects were required to remain completely still during exposure, even to the point of holding their breath. Outdoor photography was subject to sun, clouds and the rustle of wind through trees that created motion.

Stereo photographs, taken using a camera with twin lenses, were popular and required a specialized viewer to experience the image in three dimensions. The albumen photographic process was in vogue in photographers’ studios as well, utilizing the albumen of egg whites to bind chemicals to a thin piece of paper. Accompanying the albumen process was the carte de visite, a small albumen photograph mounted on thicker paper measuring slightly more than 2 by 3½ inches. The carte de visite was relatively inexpensive to produce, allowing family members to exchange photographs with one another or collect the images of famous people, much like boys of later generations would collect baseball cards. The carte de visite often served as the last remembrance of a young soldier marching off to war.

When Lincoln sat for Gardner in February 1865, it was his seventh session with the photographer, who had earned a measure of fame in his own right by documenting the individuals and events of the day, particularly the battlefields of Antietam and Gettysburg, where Robert E. Lee’s two Confederate invasions of the North were turned back in defeat in 1862 and 1863. Later, Gardner was the only photographer authorized to record the hanging of four Lincoln assassination conspirators, Mary Surratt, David Herold, George Atzerodt and Lewis Powell, in the yard of the Old Arsenal Penitentiary in Washington on July 7, 1865.

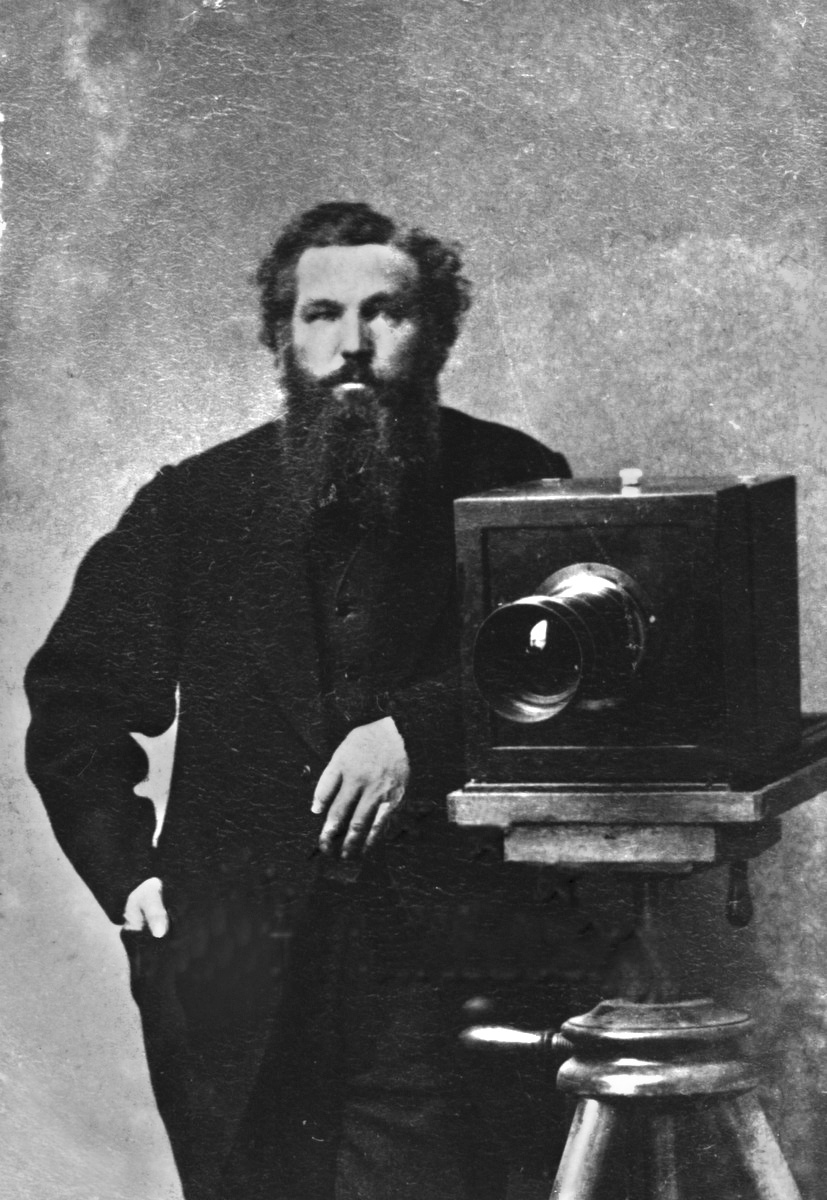

Gardner had immigrated to the United States in 1856 from Scotland, where he was already an established photographer and newspaper editor. A devout member of the Church of Scotland, he contributed to the purchase of land near the small town of Monona, Iowa, in the hopes that a socialist commune might develop there. When he reached the United States, Gardner discovered that an outbreak of tuberculosis was devastating the commune and wisely decided to remain in New York City.

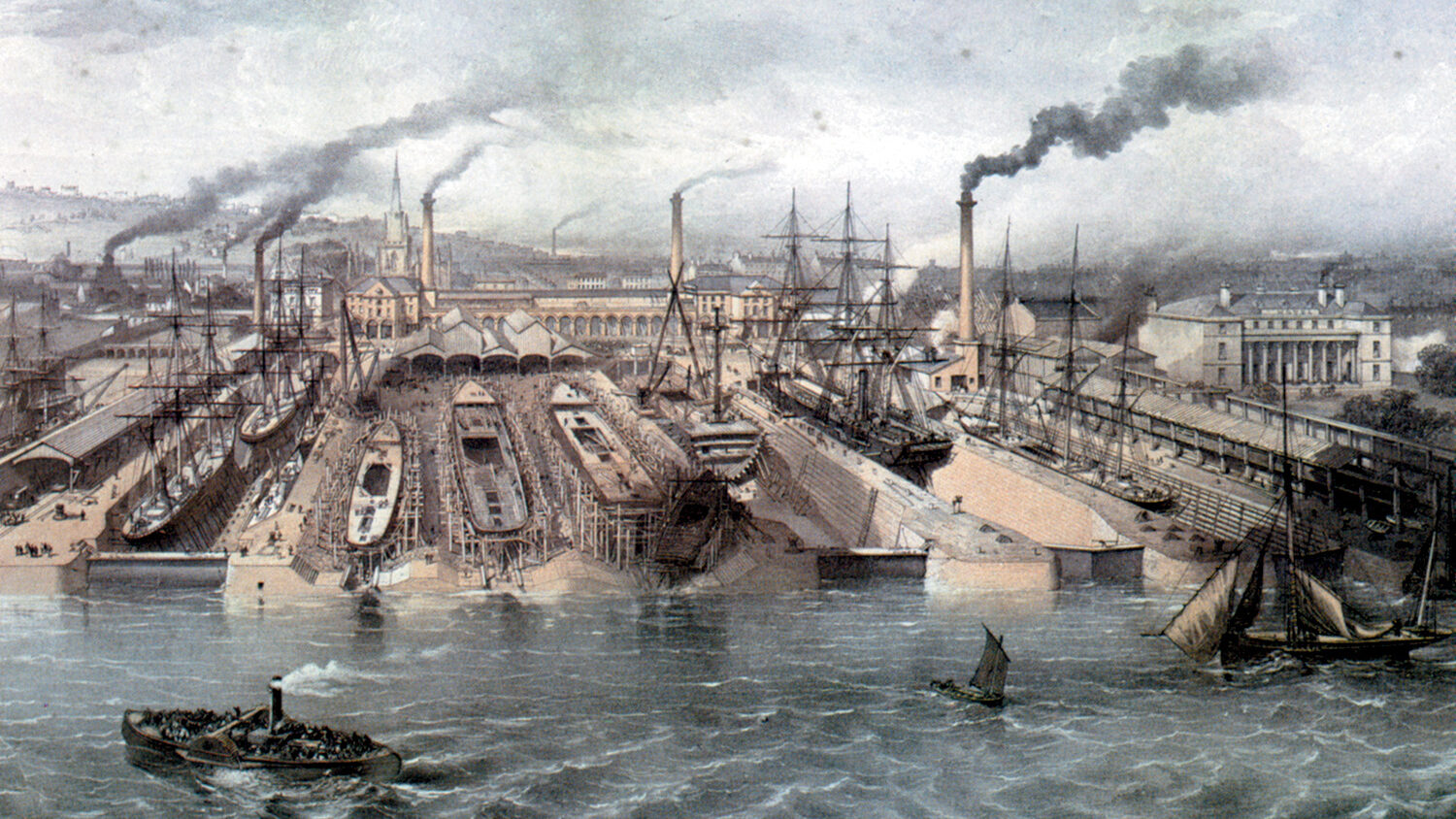

In 1851, Gardner had traveled to London and visited the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Crystal Palace Exhibition. While there, he was introduced to the photography of American Mathew Brady. Five years later, he contacted Brady and joined his New York studio. He also worked for the office of U.S. Topographical Engineers. Although the two would later part company, Gardner owed a large measure of his success to the influence and example of Brady.

Mathew Brady: The Father of Photojournalism

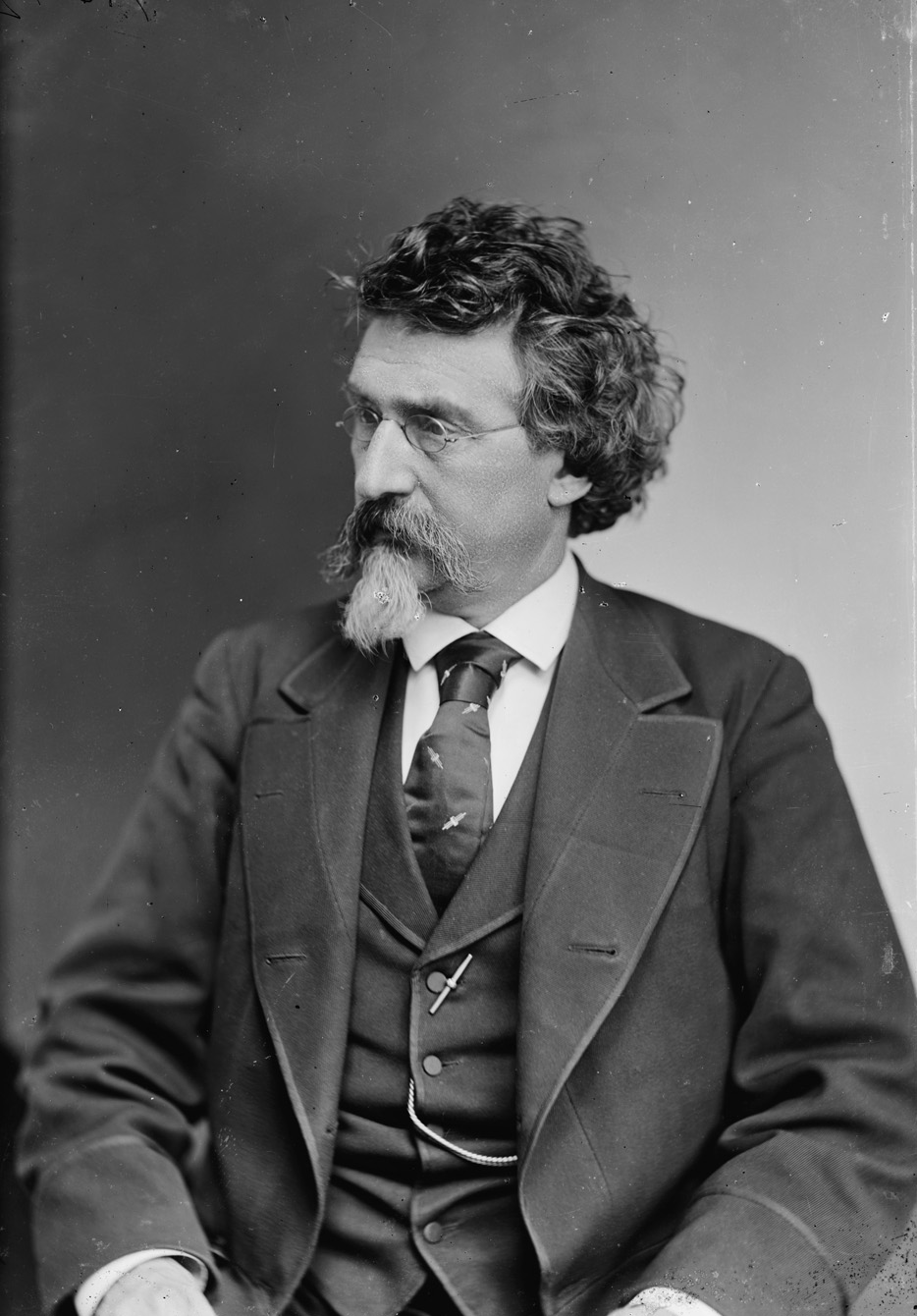

Brady is considered the father of photojournalism. He was certainly the most widely recognized names in American photography. His personal financial investment and zeal to record the events of the Civil War are largely responsible for the invaluable photographic record of the conflict. In 1858, Brady opened a Washington studio, naming Gardner its manager. By 1861, Brady deployed teams of photographers to travel across the embattled countryside to document the face of war as had never been done before.

Brady was born in Warren County, New York, between 1822 and 1824. At the age of 16, he ventured to New York City and found work as a department store clerk. A student of the portrait artist William Page, he started his own business painting miniature portraits and making cases for daguerreotype photographs and jewelry. Through Page he was introduced to Samuel F.B. Morse, a portrait artist and professor of art, painting and design at New York University who was later credited (perhaps wrongly) with the invention of the telegraph and a transmitting code that bears his name.

Morse had traveled to France in the 1830s and become interested in photography. When he returned to the United States, he established a studio, offering classes in the process. Brady enrolled in 1844, opened his own studio, and gained notoriety photographing well-known figures of his day. Among his subjects were an elderly Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, Millard Fillmore, Daniel Webster, Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun.

Brady published an album of engravings from these daguerreotypes titled The Gallery of Illustrious Americans and advertised the exhibition of his photographs in Doggett’s New York City Directory for 1850-1851. The lengthy advertisement declared: “At the annual exhibitions of the American Institute for five years, the pictures from this establishment have received the first prize, consisting of a silver medal. The last year the first gold medal ever awarded to Daguerreotypes was bestowed on the pictures from this Gallery. The portraits taken for the ‘Gallery of Illustrious Americans,’ a work so favorably received throughout the United States, are engraved from these Daguerreotypes. Strangers and citizens will be interested and pleased by devoting an hour to the inspection of Brady’s National Gallery, Nos. 205 and 207 Broadway, corner of Fulton-street, New York.”

The Photography Business and War

Brady’s business surged with the coming of the Civil War as soldiers paused to sit for cartes de visite. Sometimes the wait for a sitting could extend to hours. For several years, the photographer himself had urged potential customers to pose because life could be short. In 1856, he advertised in the New York Tribune, “You cannot tell how soon it may be too late.” It would prove to be a prescient warning.

For Brady, the war presented more than just an increase in studio patronage. Photographing it extensively might also prove to be commercially viable. Photos of the battlefields and other subjects might be exhibited and the images sold to private interests or to the federal government. A week before the first major engagement of the war, the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861, Brady petitioned Lincoln for permission to travel with the Union Army and photograph the battle. When asked later about his motivation, Brady replied, “I felt I had to go, a spirit in my feet said go, and I went.”

Two wagons stocked with photographic chemicals served as traveling darkrooms. Brady drove one of these, accompanied by a newspaper reporter named Dick McCormick and Harper’s Weekly sketch artist Alfred Waud. Brady’s assistant, Ned Hause, drove the trailing wagon. Although Brady is said to have taken a number of photographs during his ride to Bull Run, none of the actual battle appear to have survived. Brady himself was caught up in the hasty retreat of defeated Union soldiers and Washington dignitaries who had ventured gaily onto the field. He spent a night in the woods, lost and alone, before making his way back to the capital the following day.

In a bizarre twist, one reporter blamed the Union stampede on Brady’s camera. “Some pretend, indeed, that it was this mysterious and formidable instrument that produced the panic,” Brady wrote. “The runaways, it is said, mistook it for the great steam gun discharging five hundred balls a minute, and took to their heels when they got into focus.” Onlookers asserted that Brady had shown more courage that many of the soldiers. “The public is indebted to Brady of Broadway for his excellent views of grim visaged war,” noted Humphrey’s Journal. “He has been in Virginia with his camera, and many and spirited are the pictures he has taken. His are the only records of the flight at Bull Run. Brady has shown more pluck than many of the officers and soldiers who were in the fight.”

In the wake of the notoriety stirred by his Bull Run experience, Brady was convinced that public demand for his “war views,” would mean commercial success. He sought permission to continue his work documenting the war, recalling later, “By persistence and all the political influence I could control, I finally secured permission from [Edwin M.] Stanton, the Secretary of War, to go onto the battlefields with my cameras.”

Brady’s Photographers

Brady employed at least 20 photographers, who traveled to the scenes of major battles and compiled an invaluable photographic record of the Civil War. Foremost among Brady’s field photographers were Alexander Gardner, Timothy O’Sullivan, James Gibson, George Barnard and Thomas Roche. He also bought negatives and images from photographers who were not under his direct supervision. Problems with his eyesight plagued Brady throughout his life, and his limited visits to the field following Bull Run were mainly supervisory in nature.

Brady personally financed his wartime photographic venture, spending as much as $100,000 to produce more than 10,000 plates. However, the expected return on his investment did not materialize. A potential sale to the New York Historical Society failed, and a decade after the war ended the financially strapped photographer sold his entire body of work—some 5,712 photographs—to the federal government for only $25,000. The purchase was largely due to the efforts of U.S. Congressman and future President James A. Garfield, himself a Union veteran.

During his Civil War documentary effort, Brady published and exhibited the work of his photographers and others with the credit line “Photograph by Brady” or “Brady’s Album Gallery.” Both Gardner and Gibson copyrighted their images, and the information appears in fine print on the edge of album cards and stereo views that were published by Brady in 1862. However, most of the praise and publicity went to Brady himself, since few individuals bothered to look at any of the fine print.

The situation created friction with the actual photographers who had produced the published images. It led to the split in late 1862 with Gardner, who subsequently hired away several of Brady’s photographers. The real reason for the rupture between Brady and Gardner remains lost to history, although financial issues may also have contributed to it. As early as 1861, suppliers were unwilling to extend credit to Brady, and by the end of the war he had acquired a mountain of debts along with his trove of photographs.

After the war, Brady continued to work in Washington, operating studios in no fewer than seven locations through the years, including the home of his nephew, Levin Handy. In 1868, one postwar studio was sold at auction to pay creditors. He later bought back the studio and sued Gibson, its former manager, for losses incurred. On January 15, 1896, Brady died penniless in the indigent ward of Presbyterian Hospital in New York City due to complications from an accident suffered a year earlier involving a horse-drawn streetcar as he was preparing to deliver a lecture at Carnegie Hall. The New York 7th Regiment Veterans Association paid the expenses for Brady’s Washington funeral, and he was buried beside his wife in Congressional Cemetery.

Photographing Antietam

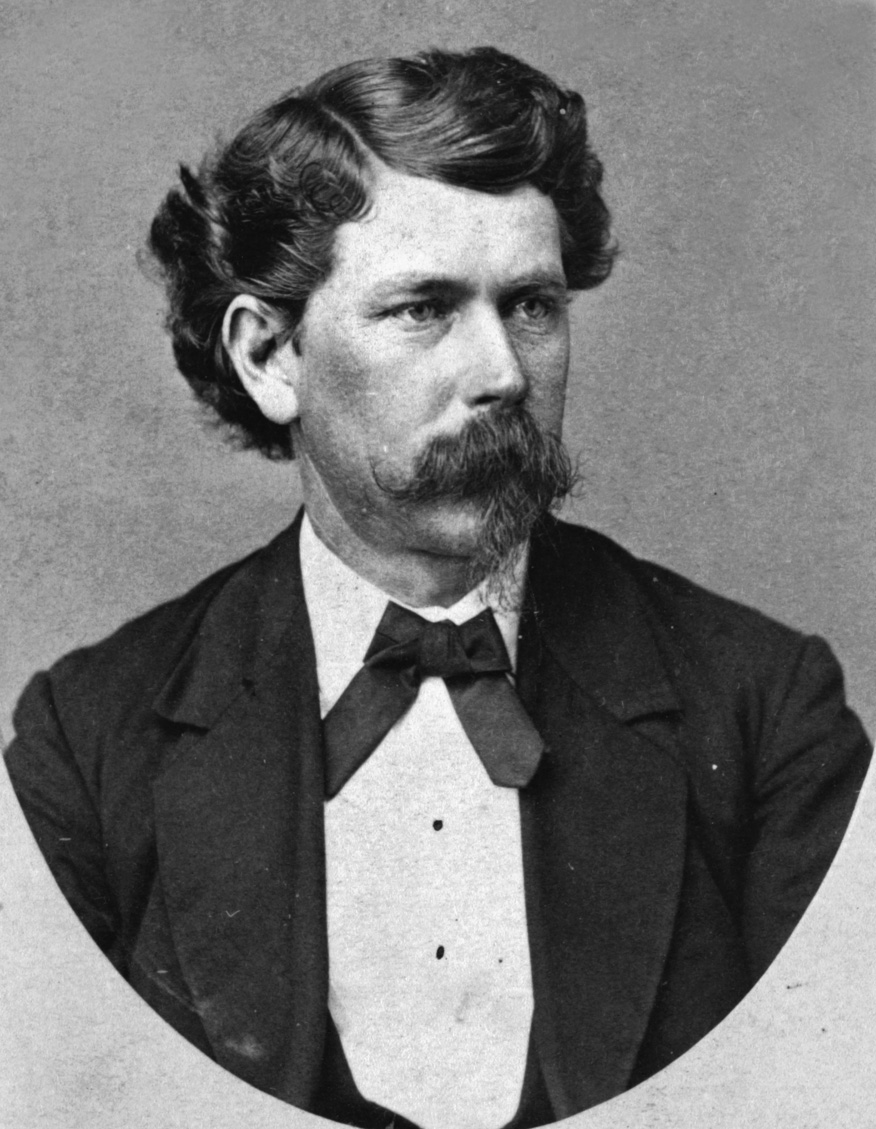

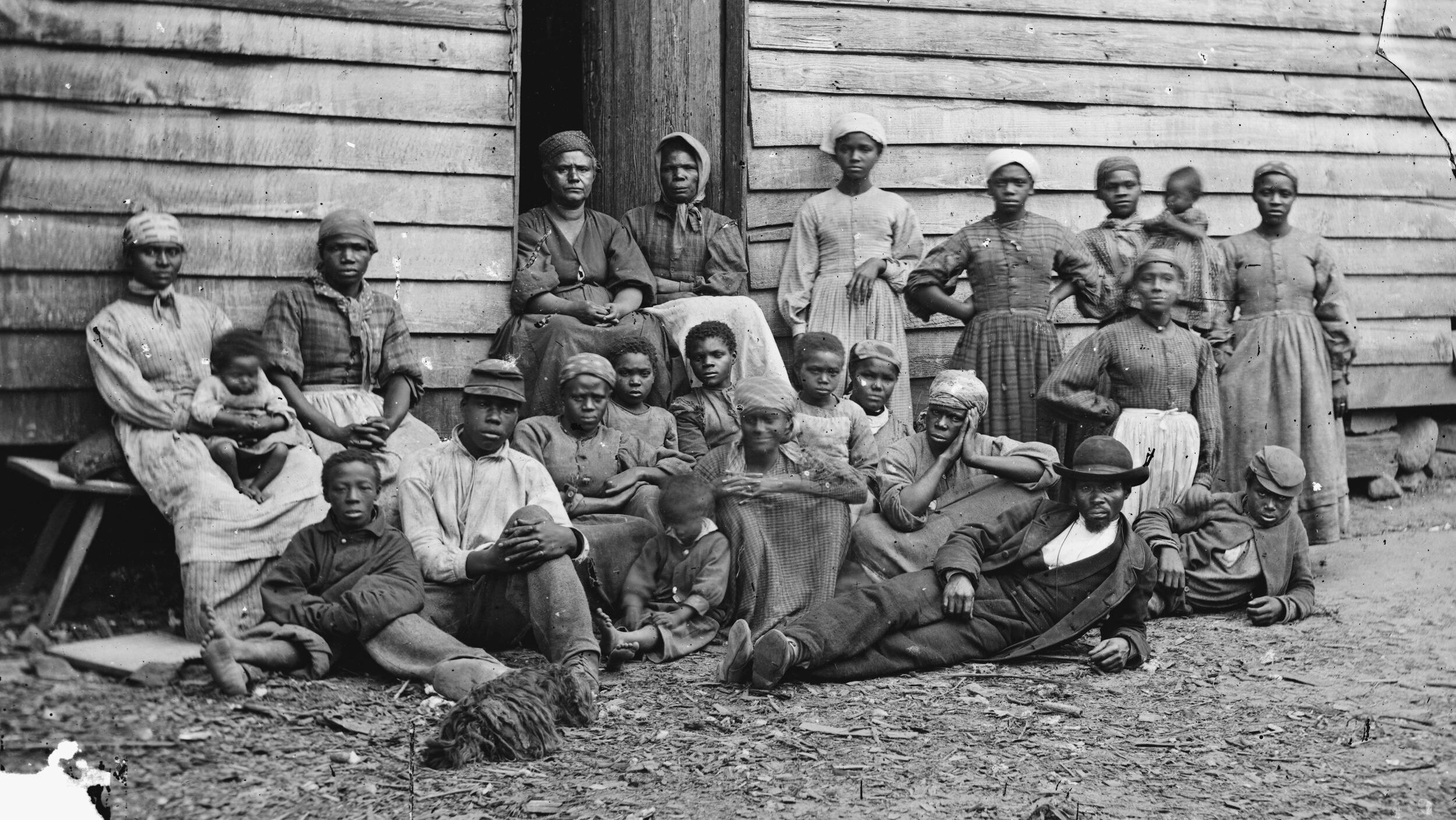

By late 1861, Brady employee Timothy O’Sullivan was photographing Union operations in South Carolina, where a Federal army under Brig. Gen. Thomas Sherman was establishing bases near Hilton Head and Beaufort. Born in New York in 1840, O’Sullivan had begun working for Brady as a teenager. He subsequently left Brady to work with Gardner and recorded some of the most famous photographs of the war on the Gettysburg battlefield and during the grinding Union offensive in the spring of 1864, which included the battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor and Petersburg.

Barnard and Gibson, both Brady employees at the time, photographed the Bull Run battlefield and the area surrounding the town of Manassas, Virginia. Gibson followed Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign in the spring of 1862 and recorded images of the Union supply base at Yorktown, Virginia, and the battlefields of the Seven Days.

In the late summer of 1862, Lee’s first invasion of the North, culminating in the Battle of Antietam on September 17, provided a tremendous opportunity for Gardner and Gibson. Gardner was still managing Brady’s Washington gallery at the time and was assigned to serve as an official photographer for McClellan, then commanding the Army of the Potomac. Gardner was well aware that events were rapidly unfolding in western Maryland, and he and Gibson journeyed together to the town of Sharpsburg, arriving even before the Confederate Army had begun its withdrawal into Virginia.

Within hours of the conclusion of the battle, the two were at work. The result was startling. Never before had photographers been in position to record such scenes of chaos and carnage while bodies were still unburied, lying in heaps where the soldiers had fallen. Gardner and Gibson exposed 70 plates within five days of the battle, recording stark images of twisted, contorted and mangled bodies, some dismembered or with dried blood streaking cheeks or foreheads, bloated and with sightless eyes. They made memorable photographs of dead Confederate soldiers from Louisiana heaped next to a rail fence along the Hagerstown Turnpike, photos of bodies lying on the gently rolling ground before the Dunker Church, and jumbled corpses piled in the deathtrap of Bloody Lane. A Confederate colonel’s dead horse, posed as though asleep, was strangely haunting.

By the end of October, the Antietam negatives had reached Brady’s studio in New York, and prints were quickly put on display for public viewing. The response was electrifying. New Yorkers flocked to see these stark, surreal glimpses of war. The New York Times was prompted to comment in an October 30 editorial. “The living that throng Broadway care little perhaps for the Dead of Antietam, but we fancy they would jostle less carelessly down the great thoroughfare, saunter less at their ease, were a few dripping bodies, fresh from the field, laid along the pavement. As it is, the dead of the battlefield come up to us very rarely, even in dreams. We see the list in the morning paper at breakfast, but dismiss its recollection with the coffee. We recognize the battle-field as a reality, but it stands as a remote one. It is like a funeral next door. The crape on the bell-pull tells there is death in the house, and in the close carriage that rolls away with muffled wheels you know there rides a woman to whom the world is very dark now. Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along our streets, he has done something very like it.”

Gettysburg Immortalized

Within months, Lee’s second invasion of the North ended in disastrous defeat at Gettysburg. Three days of heavy fighting on July 1-3, 1863, left the small southern Pennsylvania town overwhelmed with the dead and wounded of both sides. Now self-employed, Gardner, along with associates O’Sullivan and Gibson, whom he had successfully lured from Brady’s service, once again arrived with their horse-drawn traveling darkroom before many of the bodies were buried. Gardner and company produced 60 negatives during their Gettysburg venture, concluding their work by midday on July 7.

Brady led another team of photographers to the area about a week later and supervised their work, eschewing the camera himself due to his failing eyesight but actually appearing in some of the photographs wearing a long jacket and straw hat. Brothers Charles and Isaac Tyson, operators of a local portrait studio, fled the town during the battle and returned to photograph prominent locations later in the summer.

The photographic record of the Battle of Gettysburg brought lasting fame to such scenes of carnage as Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, the Peach Orchard, the Wheatfield, Little Round Top, Devil’s Den, the Slaughter Pen and the Rose Farm. Gardner, O’Sullivan and Gibson again produced compelling death studies, and although the battlefield had been cleared of bodies by the time Brady arrived and the Tysons began their work, their frames are also historically significant for depicting the battlefield as it appeared in 1863.

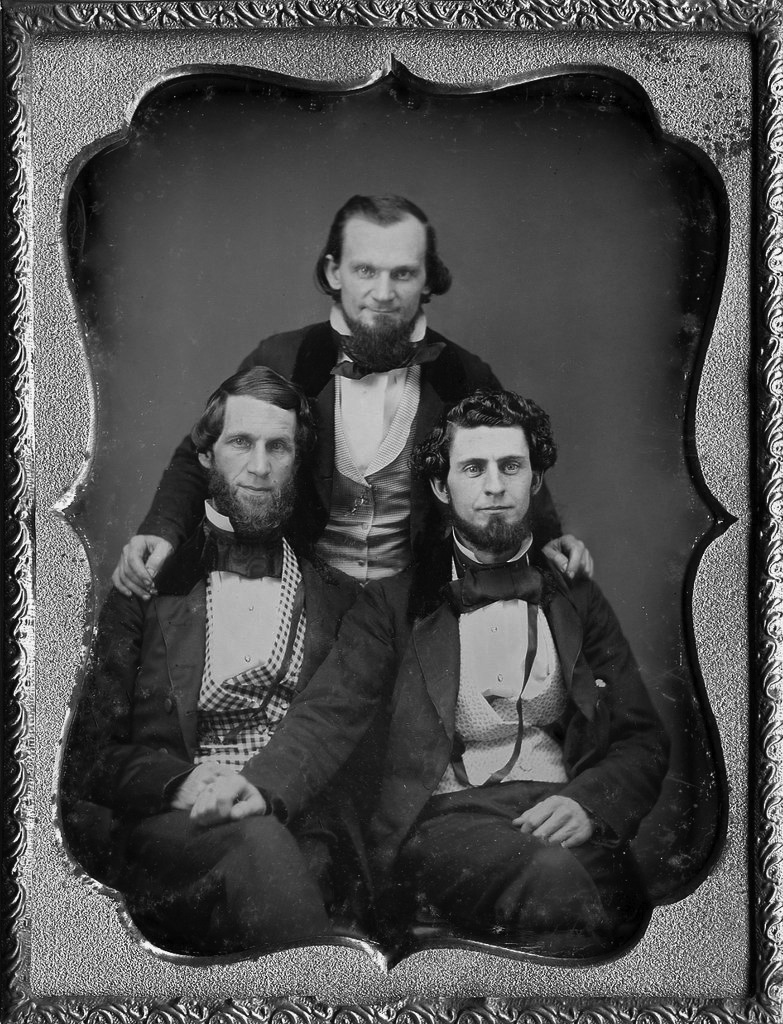

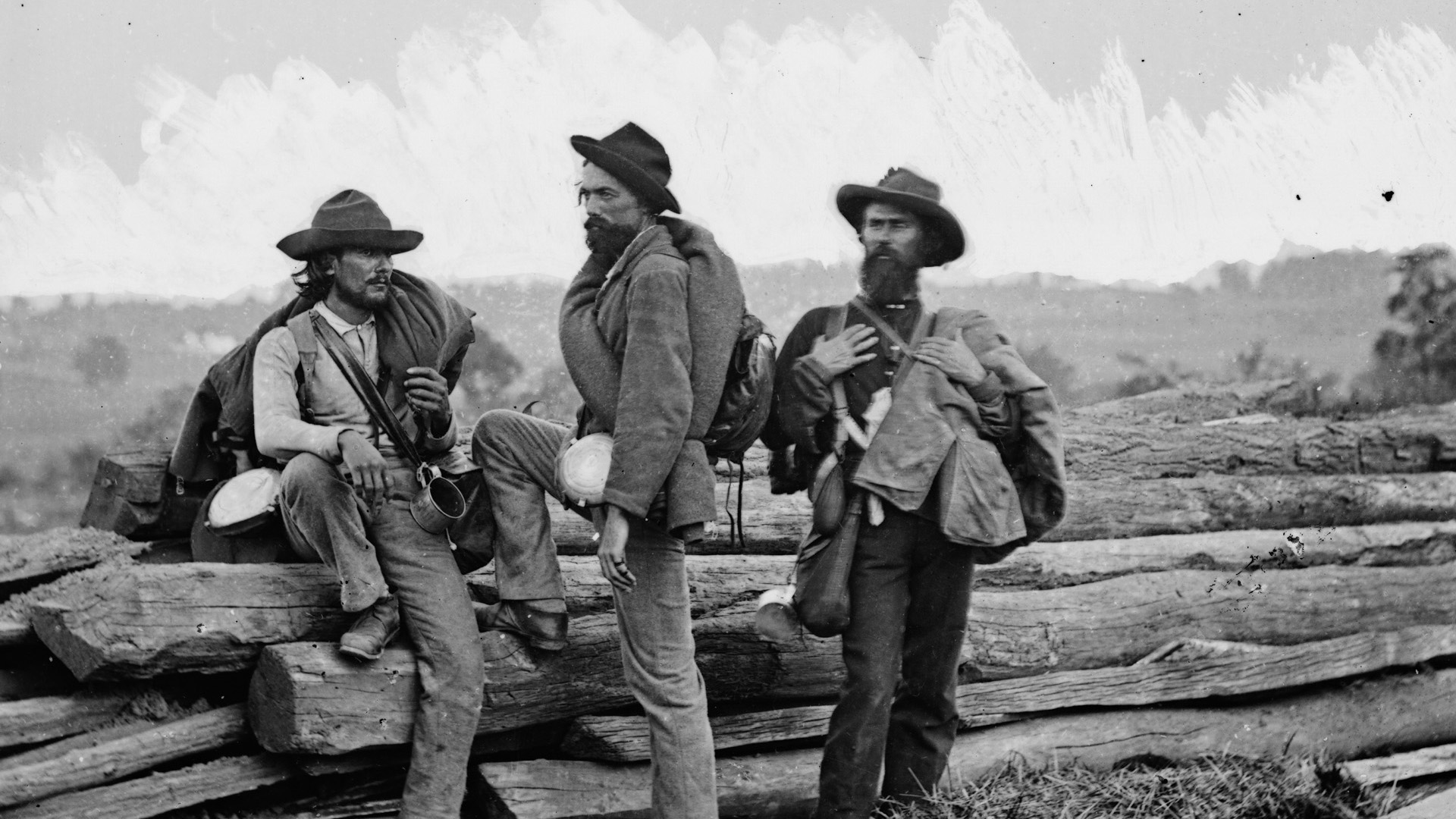

Among Brady’s best known images at Gettysburg were photos of a trio of Confederate prisoners posing along a rail fence on Seminary Ridge and a view of elderly Gettysburg civilian John Burns, who took up his musket and joined Union troops during the fighting. The Tyson works include the sprawling hospital at Camp Letterman, the field headquarters of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, and panoramic views of the town and its environs.

One of the most famous photographs of the Civil War, depicting a dead Confederate soldier lying next to a hastily stacked stone wall, was taken by O’Sullivan on July 6, and remains the topic of much theory and conjecture. Although some historians maintain that the photograph is authentic, photography expert William A. Frassanito asserts that the dead Confederate, labeled a “sharpshooter” by Gardner, had in fact appeared in previous photos and was moved approximately 40 yards to the final position. A rifle used as a prop in other photographs taken by the Gardner trio was placed against the stone wall to complete a touching tableau of glorious youth lost to the horrors of war.

In another O’Sullivan photograph, dead soldiers originally believed to be casualties of the Union 24th Michigan Infantry Regiment from the fabled Iron Brigade gathered for burial at McPherson’s Woods, were actually dead Confederates of either the 53rd Georgia or 15th South Carolina Regiment. Gardner grimly captioned the photograph “A Harvest of Death,” and apparently shared that caption with a second scene depicting Union soldiers killed defending the left of the Army of the Potomac at Devil’s Den, the Rose Farm or along the Emmitsburg Road.

When Philp & Solomons of Washington published the first edition of Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War in 1865, Gardner supplied the accompanying text for the images. In the flowery prose of the day, he wrote: “Slowly, over the misty fields of Gettysburg—as all reluctant to expose their ghastly horrors to the light—came the sunless morn, after the retreat by Lee’s broken army. Through the shadowy vapors, it was, indeed, a ‘harvest of death’ that was presented; hundreds and thousands of torn Union and rebel soldiers—although many of the former were already interred—strewed the now quiet fighting ground, soaked by the rain, which for two days had drenched the country with its fitful showers.”

“A Council of War at Massaponax Church, Virginia”

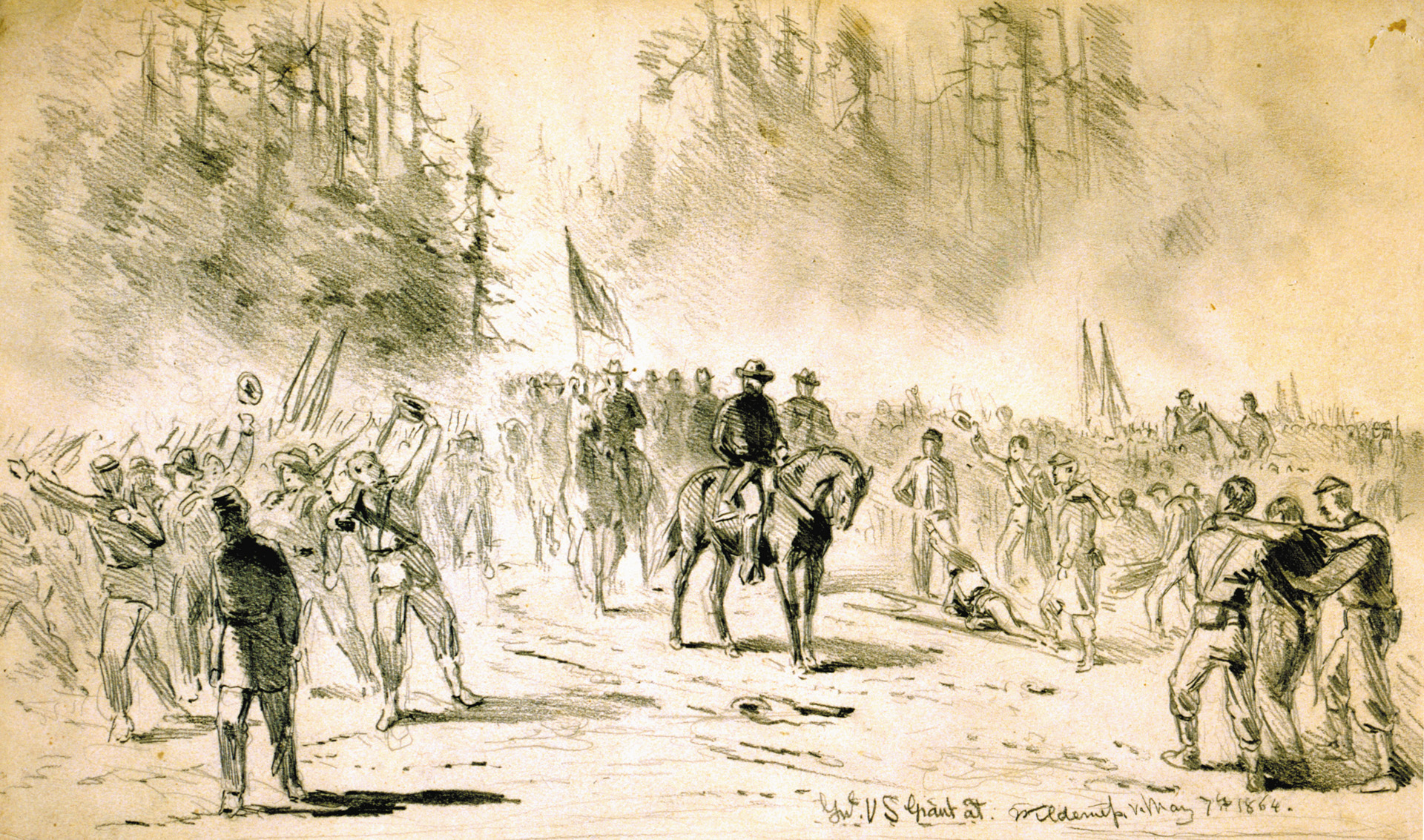

In the spring of 1864, Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade’s Federals struck southward with commanding general Ulysses S. Grant accompanying them. The costly campaign in northern Virginia included skirmishes along the banks of the North Anna River and a major crossing by Union troops at the river. Heavy fighting took place in the Wilderness and at Spotsylvania. The nine-month siege of Petersburg, a rail junction town 23 miles south of the Confederate capital of Richmond and the key to the eventual Union capture of the city, followed.

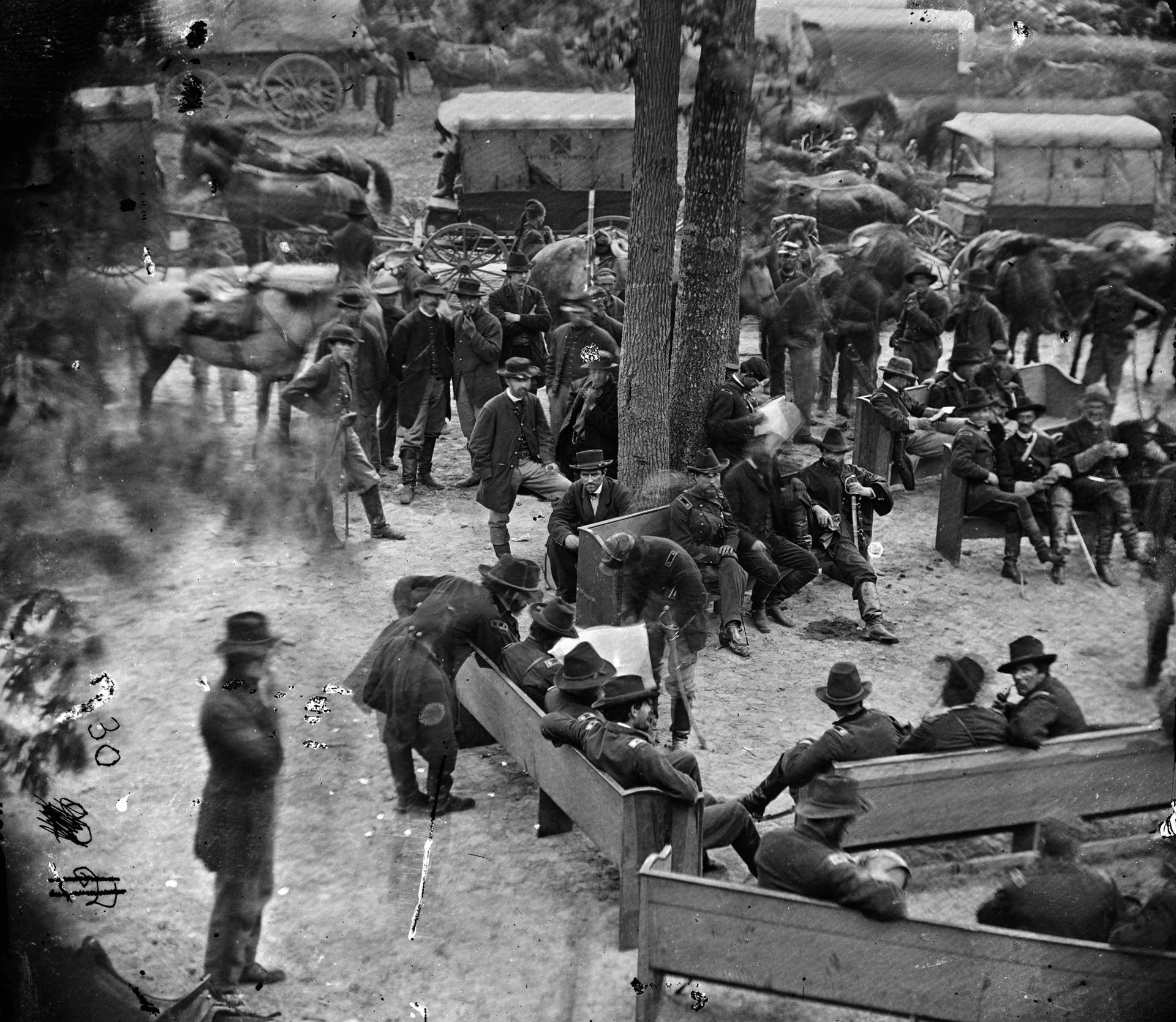

On May 21, O’Sullivan found himself in the proverbial right place at the right time. Along the route from Spotsylvania Court House to Guiney’s Station, Grant and Meade stopped at the Massaponax Church, a brick structure built by a local Baptist congregation founded in 1788. Grant ordered that pews be carried outside and arranged beneath the cover of pine trees in the yard. O’Sullivan asked permission to photograph the meeting of the highest ranking Union officers and their staffs in the field. Carrying his heavy camera and equipment to the front window of the second story of the church building, O’Sullivan recorded a remarkable sequence of photographs. Titled “A Council of War at Massaponax Church, Virginia,” the series depicted Grant, Meade and staff officers reading newspapers and resting. In one photo, Grant sits calmly smoking a cigar. In another, he leans over Meade’s shoulder to view a map, and in a third he scribbles an order to IX Corps commander Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside.

Capturing Death on the Battlefield

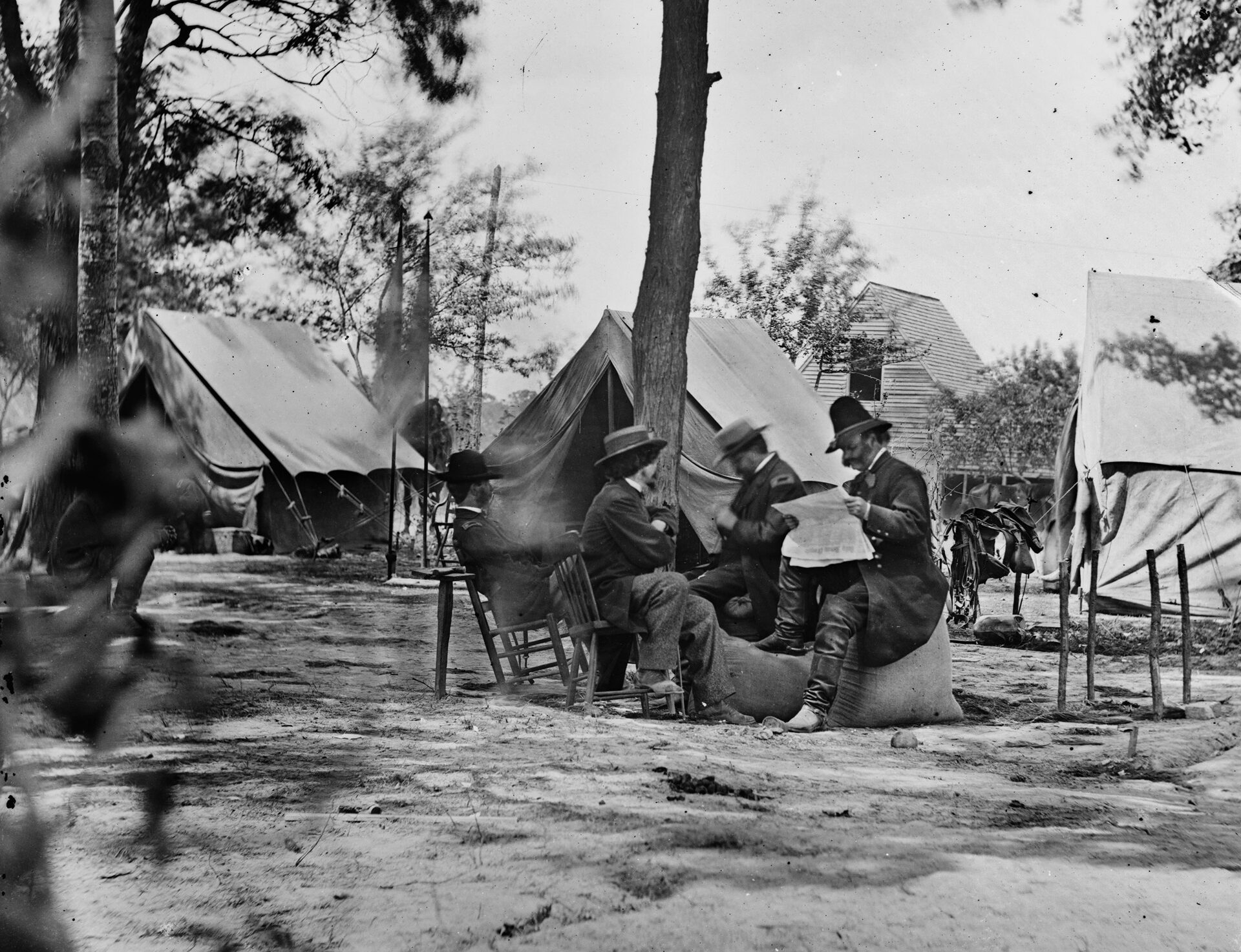

A team of Brady photographers also operated during the spring campaign in Virginia. Eventually, Brady himself joined the group at Cold Harbor, where they recorded an iconic image of Grant leaning against a pine tree in front of his headquarters tent. Several other Union generals, including Meade, were photographed at Cold Harbor, where the Army of the Potomac suffered horrific casualties in ill-conceived frontal assaults against well-entrenched Confederate veterans. Whenever possible, Brady liked to include himself in at least one negative exposed during a field series. At Cold Harbor, he is pictured seated across from Burnside.

Nearly a year after the fighting at Cold Harbor, John Reekie, an associate of Gardner, took a macabre photograph of black laborers exhuming the decomposing corpses of Union soldiers killed in the battle. Captured during the relocation of the bodies to permanent resting places, the image reveals the partially skeletal remains of at least five dead soldiers, their skulls lying atop the ragged remnants of uniforms. A trouser leg and shoe hang limply, presumably obscuring a decomposing limb.

Numerous death studies were done at Petersburg following the climactic battles of the lengthy siege. The most notable of these may be attributed to photographer Thomas C. Roche, previously employed by Brady and in the spring of 1865 apparently working independently or in the employ of New York publishers and suppliers E. & H.T. Anthony & Co., which Brady had also contacted for publication and marketing support as his financial situation began to deteriorate. Roche exposed plates of numerous Confederate dead inside the recently captured breastworks of Fort Mahone. At least two of these depicted the ashen faces of dead young Confederates apparently only in their teens.

While the extensive photographic record of the Civil War in the East was being compiled, George Barnard photographed major campaigns and battlefields in the West from 1863 to 1865, including Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, prominent during the Battle of Chattanooga in southeast Tennessee, and Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s Atlanta campaign, the March to the Sea and the capture of Savannah, Georgia, and Columbia, South Carolina, the capital of the “Cradle of Secession.” In 1866, an album titled Barnard’s Photographic Views of the Sherman Campaign was published in New York by Wynkoop & Hallenbeck.

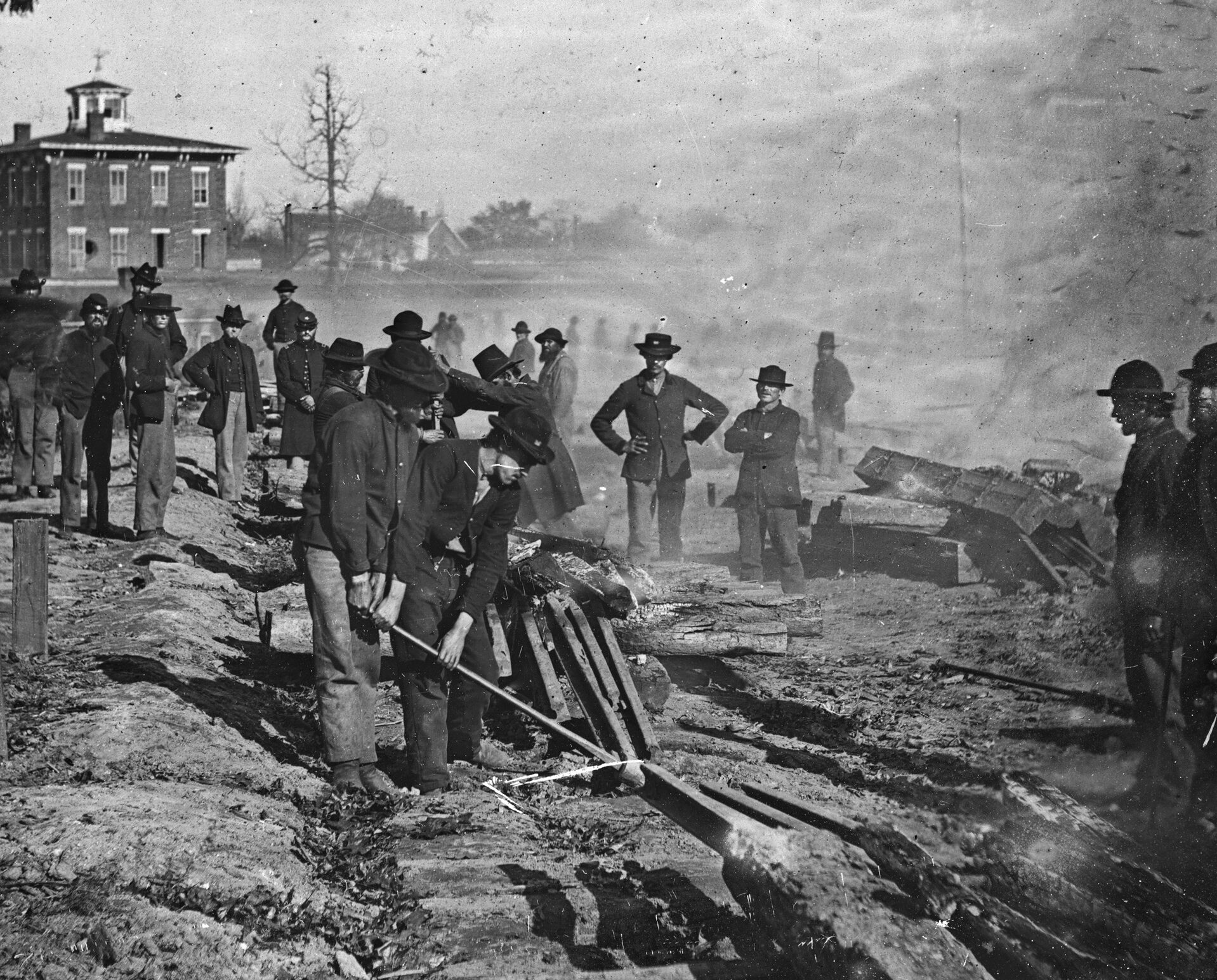

Sherman’s notorious “bummers” destroy a section of railroad

at Atlanta, Georgia, in the summer of 1864. Photographer George N. Barnard was one of the few to record the Civil War in the Western theater.

The Confederacy’s Photographers

Although they often struggled with limited supplies of chemicals and other necessities and many of their negatives were destroyed as the war progressed, Southern photographers plied their craft as well. In the city of Charleston alone there were seven portrait studios in operation on fashionable King Street on the eve of the Civil War. Among the most prominent Southern photographers was George S. Cook, born in Connecticut in 1819. After a failed attempt to establish himself as an artist in New Orleans, he came to Charleston and opened his studio at 265 King Street.

On September 8, 1863, Cook brought his camera and equipment to Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor and attempted to photograph action between the Union gunboat New Ironsides, the grounded monitor Weehawken, and five other monitors, Passaic, Montauk, Patapsco, Lehigh and Nahant, which were engaging Confederate batteries at Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie on nearby Sullivan’s Island.

Some photo historians credit Cook with taking the first combat photos in history. These included the image of a shell from Weehawken exploding inside Fort Sumter and two exposures from the fort’s parapet that appear to show New Ironsides and the monitors wreathed in smoke as they fire on the Confederate fort. One contemporary account supporting Cook’s efforts came from none other than Timothy O’Sullivan, who penned his wartime reminiscences in 1869. O’Sullivan wrote that Cook was a “courageous operator who stuck to his work, and the pictures made on that occasion are among the most interesting of the war.” Cook and his assistant, J.M. Osborne, worked with only a single lens camera and improvised to produce a stereo depiction of the Union ships by moving his camera slightly between exposures. The foreground is prominent in both of the naval photos, due to the fact that Cook was under fire at the time and had to keep low as he worked.

At first glance, the frame appears to be of a nondescript camp scene along a broad beach. Curiously, the men in the photograph have their backs turned to the camera, apparently watching something of interest. On the distant horizon, New Ironsides, Weehawken and the other Union ships are engaged with the Confederates at the two forts. Although the image is distant, it appears that New Ironsides has just fired one of her 11-inch Dahlgren cannon and is trailing a longboat, while the stacks and pilothouses of the monitors are faintly visible.

At least two other photos vied for attention as actual Civil War combat images. One of these, discredited in the 1960s, is a Gardner frame taken on a hillside near the Pry House, McClellan’s headquarters during the Battle of Antietam. The scene depicts a seated man surveying the battlefield toward Bloody Lane with a Union artillery battery in the left distance and smoke emanating from out of the frame to the right. Once thought to be smoke from rifle fire, the plumes were later determined to be from campfires, while the nearby artillery battery is at rest and remains limbered.

The other is purportedly of a Confederate shell exploding near Union engineers at Dutch Gap Canal in Virginia in 1864. Photographed by either Roche or A.J. Russell, soldiers in the frame appear to be relatively at ease rather than taking cover against incoming artillery fire. Russell later maintained that Roche had exposed himself bravely to enemy fire to capture the image.

Brady’s Photographers After the War

After the war, the most recognized photographers continued their craft, at least for a while. Gardner became the official photographer for the Union Pacific Railroad and was active in Kansas. He also photographed numerous Native Americans who came to Washington for audiences with government officials, but later apparently chose to discontinue his photography enterprise and worked in life insurance. He died after a short illness in 1882 at the age of 61.

O’Sullivan traveled extensively in the American West, working for the U.S. government to record images of the Navajo and Pueblo tribes. In 1870, he joined a team in Panama that was surveying the potential course of a canal across the isthmus. Later, he became the official photographer for the U.S. Treasury Department and the U.S. Geological Survey. He died of tuberculosis in Staten Island, New York, in 1882—the same year as Gardner—at the early age of 42.

Gardner, O’Connor, and dozens of other photographers endeavored to document the Civil War. Whether for financial gain, adventure, fame or a combination of all three, they left behind a legacy of photojournalism that has provided subsequent generations of Americans an unparalleled glimpse of life during the great conflict. Never before had warfare been so extensively documented. Unfortunately, for both America and the rest of the world, there would be no shortage of new wars—and new horrors—in the 150 years since the end of the Civil War, and photographers would be there to see them, and to act as the public’s eyes and ears.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments