By Mason B. Webb

When it came to advanced military technology in World War II, arguably no one was better at it than Nazi Germany, whose scientists Adolf Hitler keep busy trying to invent the ultimate “super weapon” capable of defeating his enemies.

For a while, it seemed that Germany might just succeed. After all, it was the Germans who had created, tested, and deployed the V-1 flying bomb, the V-2 ballistic missile, the Fritz X glide bomb, and a family of jet-powered aircraft. German tanks were, in many respects, superior to American tanks. Only in the race to build an atomic bomb were the German scientists lagging behind the United States and Great Britain.

During Operation Avalanche—the invasion of Salerno, Italy, on September 9, 1943—the Allies had their first encounter with German drones. After Allied landing craft deposited infantry on the beaches south of the city, the battleships, cruisers, and destroyers accompanying the troop transports became targets of an unexpected new weapons system: a radio-controlled glide bomb called the Fritz X.

The Fritz X (also known variously as the Ruhrstahl SD 1400 X, Kramer X-1, FX 1400, and PC 1400X) was 11 feet long, had four stubby wings, carried 705 pounds of amatol explosive in an armor-piercing warhead, and had an operational range of just over three miles. It could reach a speed of 770 mph—faster than any aircraft of the day.

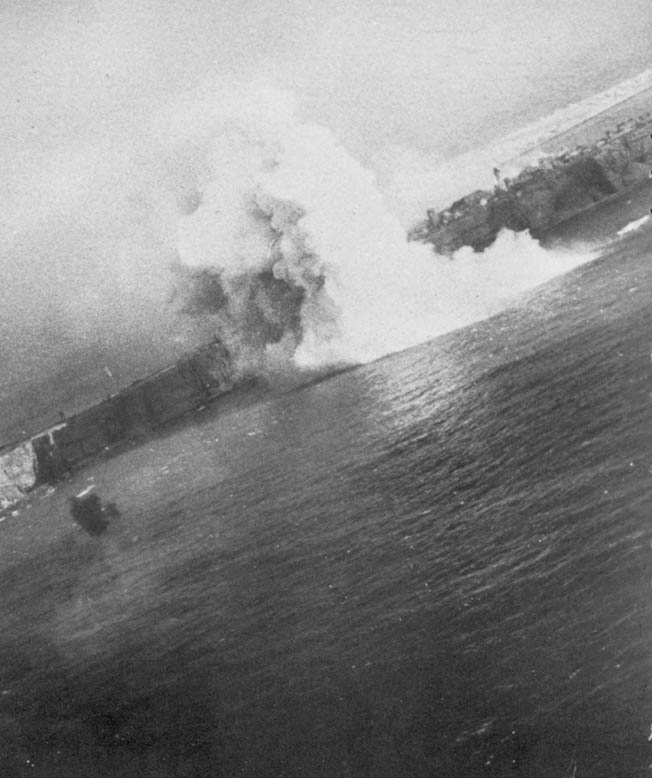

Early on September 13, a Dornier Do-217 K-2 bomber released a Fritz X from an altitude of 18,700 feet; gunners aboard the USS Savannah (CL-42), a 9,475-ton Brooklyn-class light cruiser, saw the missile and tried to shoot it down as it streaked toward them, but without success. The drone slammed into the top of a 6-inch gun turret and penetrated deep into Savannah’s hull before exploding and killing 197 sailors and wounding 15 more. Only through sheer luck and incredible bravery on the part of her remaining crew was the badly damaged ship able to make port in Malta.

That drone was one of several used against American warships on September 13. Others barely missed the cruiser USS Philadelphia, while the British light cruiser HMS Uganda was hit that same afternoon; two cargo ships may also have been struck. Three days later, the British battleship HMS Warspite was also hit by a guided bomb but remained afloat.

The United States was shocked by the technological lead the Germans had opened up in sky-borne weapons. Of course, by August 1944, the United States was already well along in its development of an atomic bomb, but in other aspects of weaponry America had slipped behind.

The United States began looking at ways to deliver a huge, conventional payload precisely on target. Even with the vaunted Norden bombsight, the boasted concept of “precision daylight bombing” rarely lived up to its billing.

What if, some officer in Washington D.C., said, we stuffed an unmanned bomber full of explosives and, by radio control or some other method, flew it directly into a target? The idea sounded good, especially since the United States (and Britain, too) was losing so many aviators on bombing runs over enemy-held territory. But how to accomplish it?

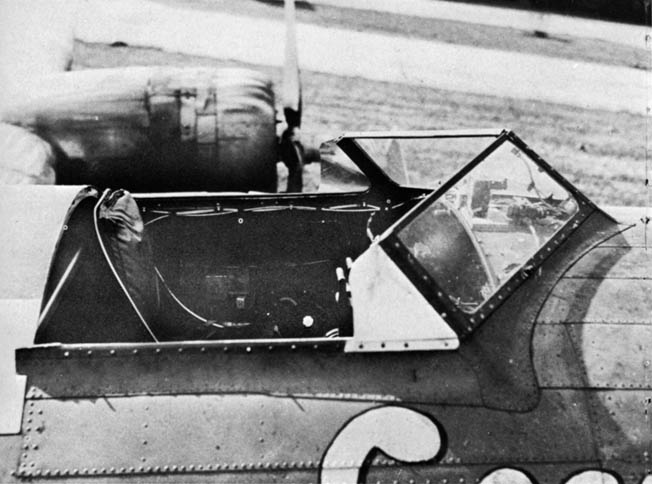

Engineers began working on the concept but discovered that it was well nigh impossible, given the technology of the time, to get a pilotless bomber to taxi and take off by remote control. The idea then evolved to a pilot and co-pilot taking off in an explosives-laden B-17 or B-24, gaining altitude, then bailing out over England while a trailing aircraft controlled the plane by radio signals, finally crashing it into the target.

On August 4, 1944, the Air Force put the concept to the test against hard-to-knock-out targets (such as V-1 and V-2 missile-launching sites, submarine pens, and deep underground installations) in what was called Operation Aphrodite.

The U.S. Army Air Forces loaded four war-weary, modified B-17 bombers, redesignated BQ-7s, each with 12,000 pounds of Torpex, which was used in both aerial and underwater torpedoes and was 50 percent more powerful than TNT.

The first test run out of RAF Fersfield, home of the 38th Bomb Group located northeast of London near Norwich, did not go well. The first B-17 took to the air and the pilots bailed out safely; the plane, however, spiraled into the ground with a resultant massive explosion near the coastal village of Orford. The second plane developed problems with the radio-control system and it, too, crashed; the pilot was also killed when he bailed out too soon. A third B-17 met a similar fate.

The fourth plane fared better, although it crashed about 1,500 feet short of its target, a massive, hardened V-2 site at Watten-Eperlecques in the Pas-de-Calais region of France, doing very little damage.

Three days later, Aphrodite was repeated––with similarly disappointing results. Two planes crashed into the sea off England, while a third was shot down over Gravelines, France. A third test resulted in a B-17 crewmember dying when something went wrong during his parachute jump; the plane continued on to its destination in Heligoland but was shot down before it reached its target.

On September 3, 1944, an Aphrodite B-17 (#63945) attempted to attack the U-boat pens at the small German coastal town of Heide, Heligoland, Schleswig-Holstein, but the U.S. Navy controller accidentally crashed the plane into Düne Island. Eight days later, in one more attempt to hit the submarine pens, another radio-controlled B-17 came close but was downed by ground fire.

As terrifying as the V-2 rockets were to those on the receiving end, the Nazis were preparing an even more diabolical weapon: the V-3 “super cannon,” also called the London Gun. When completed, the underground cannon, whose barrel was 460 feet long, was supposedly capable of firing in an hour five 300-pound shells more than 100 miles. The muzzle velocity of the monster gun was estimated to be almost 5,000 feet per second. In September 1943, German engineers had begun preparing a site at Mimoyecques, France, from which the shells could be fired across the Pas de Calais and into London.

The Allies were tipped off to this new weapon by the French Resistance, which also reported that slave laborers were involved in its construction. Considered even more accurate and devastating than the V-1s and V-2s, the V-3 had to be neutralized. On July 6, 1944, RAF 617 Squadron attacked the site with several five-ton “Tall Boy” bombs and essentially put the site out of commission; no V-3 shells were ever fired.

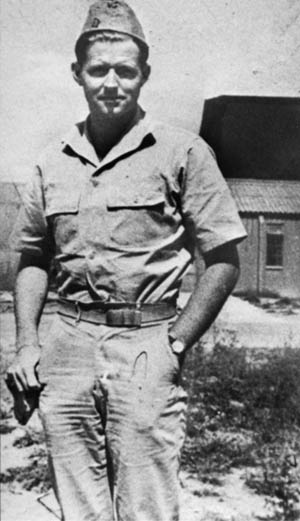

Either the U.S. Army Air Forces was not informed that the V-3 site was hors d’combat or, for some reason, decided to hit it again; an Aphrodite mission was scheduled to hit Mimoyecques on August 12, 1944. This mission would be carried out by U.S. Navy aviator Lieutenant Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., and his flight engineer, Lieutenant Wilford J. Willy flying a PB4Y-1—the Navy’s version of a B-24J Liberator. Packed into the plane’s fuselage were 21,170 pounds of Torpex.

Kennedy, of course, was the oldest son of the former U.S. ambassador to Great Britain and older brother of future American president John F. Kennedy. Willy, from New Jersey, had “pulled rank” over Ensign James Simpson, Kennedy’s regular co-pilot, to fly the mission.

On that August day, Kennedy’s plane took off from RAF Fersfield, accompanied by two Lockheed Ventura aircraft equipped with radio-control sets that would fly the bomber once Kennedy and Willy bailed out; two P-38 Lightning fighters approached to escort the BQ-18 across the Straits of Calais. A sixth aircraft, a de Havilland Mosquito camera plane, joined the formation; aboard the Mosquito was Air Force Colonel Elliott Roosevelt, one of President Roosevelt’s sons, and the commanding officer of the 325th Photographic Reconnaissance Wing.

As they approached the coast over Halesworth, Lieutenants Kennedy and Willy transferred control of their aircraft to the Venturas. Before the two men bailed out, Willy switched on a primitive television camera in the bomber’s nose that would help guide the BQ-8 to its target; Kennedy armed the 21,170 pounds of Torpex carried in 374 boxes. But then something inexplicable went terribly wrong.

At 6:20 pm, the plane suddenly disappeared in an enormous fireball, and pieces of the aircraft began raining on the rural countryside below. Hundreds of trees were destroyed, nearly 150 properties on the ground were damaged, and some 50 people on the ground were injured. Chunks of the exploding BQ-8 struck Colonel Roosevelt’s plane, but he was able to land safely. The bodies of Kennedy and Willy were never found.

Nine-year-old Mick Muttitt, a resident of nearby Darsham, told a reporter 60 years later that he and his brother were watching the formation flying about 2,000 feet above them. He said, “All of a sudden, there was a tremendous explosion and the Liberator aircraft was blown apart, with pieces falling in all directions over New Delight Wood, at Blythburgh.”

He also noted, “I vividly remember seeing burning wreckage falling earthward while engines with propellers still turning, and leaving comet-like trails of smoke, continued along the direction of flight before plummeting down. A Ventura broke high to starboard and a Lightning spun away to port, eventually to regain control at tree-top height over Blythburgh Hospital.

“While I watched spellbound, a terrific explosion reached Dresser’s Cottage in the form of a loud double thunderclap. Then all was quiet except for the drone of the circling Venturas’ engines, as they remained for a few more minutes in the vicinity. The fireball changed to an enormous black pall of smoke resembling a huge octopus, the tentacles below indicating the earthward paths of burning fragments.”

Although the cause of the disaster was never conclusively established, suspicion centered on the lack of electrical shielding material on the television camera. This is thought to have allowed electromagnetic emissions to open a relay solenoid, which in turn set off a detonator and thus the explosives.

After the Kennedy disaster, a dozen more flights ended in failure and General Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, commander of the Strategic Air Force in Europe, cancelled all further Operation Aphrodite missions.

Wilford Willy and Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., were both posthumously awarded the Navy Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross, and Air Medal. The citation for Kennedy’s Navy Cross reads: “For extraordinary heroism and courage in aerial flight as pilot of a United States Liberator bomber on August 12, 1944. Well knowing the extreme dangers involved and totally unconcerned for his own safety, Kennedy unhesitatingly volunteered to conduct an exceptionally hazardous and special operational mission.

“Intrepid and daring in his tactics and with unwavering confidence in the vital importance of his task, he willingly risked his life in the supreme measure of service and, by his great personal valor and fortitude in carrying out a perilous undertaking, sustained and enhanced the finest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

The Kennedy family, of course, was devastated by the loss of their eldest son—a son they had been grooming for great things after the war, including the hope that he would become the first Irish-Catholic president of the United States. That honor would have to wait another 16 years when John Fitzgerald Kennedy, himself a Navy war hero, attained that lofty goal.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments