By Mark Simmons

In the early hours of May 14, 1940, General Alphonse Georges, the French commander of the northeast front, received bad news at his headquarters, the small but elegant 18th-century Chateau des Bondons, an hour’s drive east of Paris near the River Marne.

He had just learned that the Germans, who had invaded his country fours days earlier, had crashed through his defenses around the city of Sedan. As he wept, most of his staff stood around in awkward silence.

When Maj. Gen. Aimé Doumenc, a member of the general staff of the Supreme Headquarters of the French Land Forces, arrived, Georges greeted him solemnly, saying, “Our front has caved in at Sedan.” He then took to an armchair, his head in his hands. Regaining some composure, he explained that two divisions had run away under heavy bombing; German tanks were reported in the small, northeastern French village of Bulson, close to the Belgian border.

Doumenc tried to inject some optimism. “Let’s look at the map, General,” he said. He showed how the three French armored divisions were still intact and could be used to pinch out the German bridgehead; the enemy could be thrown back over the River Meuse, Doumenc said, hopefully.

Georges was unconvinced. Later that day, Georges reported to General Maurice Gamelin, the Allied commander-in-chief, who also played down the crisis. A counterattack of “formidable means” was underway, Gamelin told him.

Such a counterattack looked possible on a map, but the French had been “wrong footed” from the start and never recovered. Within five days of the German invasion on May 10, Holland had been defeated, French defenses on the Meuse had fallen apart, and French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud on May 15 telephoned British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, telling him, “We have lost the battle.”

Yet this outcome at the start of the campaign was far from a certainty; the Germans were not necessarily bound to win.

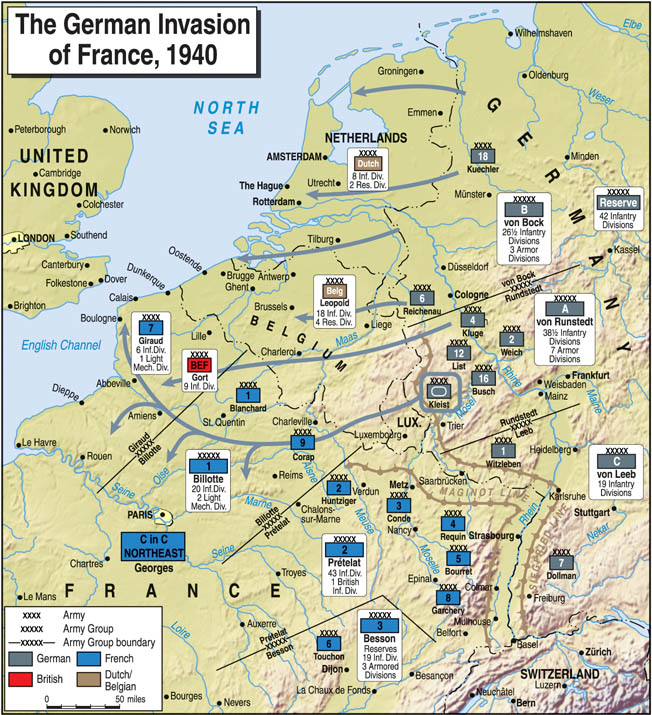

On May 10, Germany had 136 divisions in the West; 10 were armored (panzers) seven were motorized, and one was airborne. The French had 94 divisions, the British 10, the Belgians 22. The French had three armored divisions, three light mechanized divisions (similarly equipped to panzer divisions), and five cavalry divisions.

The infantry divisions on both sides, excluding the British, relied on horse-drawn transport. For example, the average German infantry division of 17,000 men had 5,375 horses, which required 53 tons of feed daily. The French alone had more tanks than the Germans: 3,254 vs. 2,574.

Although slower and with a more limited range, the French tanks were better armored and armed; the heavy Somua B tank was considered the best tank in the world. A quarter of the German tanks mounted only machine guns while another quarter had only 20mm guns. In antitank guns, the Germans had 12,800, largely of poor performance, opposed by 7,200 excellent French pieces.

It was in the organization of the armored units where there was a marked difference. Even the three French armored divisions, considerably larger than the panzer divisions, supplemented by a fourth formed during the campaign, lacked vital supporting elements such as motorized infantry, and thus were incapable of fighting independently. The panzer divisions were self-contained units of all arms and organized into corps forming a highly mobile striking force.

In the air the Germans had the advantage. In May 1940 the Luftwaffe deployed 1,016 fighters, 1,368 bombers, 342 Stuka dive bombers, and 500 reconnaissance aircraft. The French Air Force had some 1,220 modern aircraft: 700 fighters, 140 bombers, and 380 reconnaissance planes. To these were added 230 bombers and 200 fighters from Britain’s RAF, which had rushed to France and Belgium’s aid.

Clearly the Germans held the advantage, which was enhanced by superior aircraft and a better understanding, honed in Poland, of close aerial support of ground forces. The Luftwaffe also enjoyed a marked advantage in antiaircraft guns.

Thus, at the start of the campaign, Germany had an advantage only in bomber aircraft and antiaircraft defenses. Otherwise, the opposing sides were largely equal. The battle depended far more on the style of operations and the strategic concept.

The Allied high command, even before Germany’s invasion of Poland and demonstration of Blitzkrieg, had concluded that, in the event of a German attack in the West, they would seek a quick victory due to the weakness of the German economy.

With the Maginot Line forming a formidable barrier between Sedan and the Rhine River, Hitler would likely try and repeat the Schlieffen Plan of 1914, with a strike through Belgium (and likely Holland as well). The Germans were expected to advance on the Brussels-Cambrai line.

But in 1936, Belgium announced its neutrality, thus upsetting Gamelin’s plans to move large numbers of troops into Belgium and fight the battle on the neighboring country’s eastern frontier. The plan was therefore revised with the battle expected to be fought on the plains of Belgium.

However, a defect in the revised plan was to assign the highly mechanized French Seventh Army to a coastal flank operation in the hope its speed would enable a link to be made with the Dutch.

Gamelin was largely right in his analysis of German strategy. The major role in the German plan—Fall Gelb (“Plan Yellow”)—postponed several times between October 1939 and January 1940, was given to Col. Gen. Fedor von Bock’s Army Group B, with a thrust through Holland and Belgium, and Col. Gen. Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group A, with no armored units, would cover the southern flank. They only expected to seize the Low Countries and Channel coast.

General Franz Halder was ordered by Hitler to prepare the attack in the West––even before Poland had surrendered. He viewed his task with horror and secretly thought it wise to get rid of Hitler.

Von Rundstedt, after being appointed to command Army Group A on his return from Poland, felt Plan Yellow as it stood was poor, for it did not cut the Allies off from the Somme but merely pushed them back, risking the same stalemate as 1914. General Walter von Brauchitsch, the German C-in-C of the Army, did not agree.

However, on February 17, 1940, von Rundstedt’s brilliant chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Erich von Manstein, had dined with Hitler and explained that he and his commander felt the left wing should be reinforced and become the main striking force. Hitler was taken by the suggestion—a surprise attack through the Ardennes against the weakest sector of the French defenses. It was bold and held the prospect of a swift victory; it appealed to Hitler’s gambler’s instinct.

Von Rundstedt got more armor than he had asked for, as the main weight of attack was now transferred to Army Group A. Von Bock’s Army Group B was reduced to 26 infantry divisions and three panzer divisions, but it would still attack through Holland and Belgium, distracting the Allies. Army Group A, bulked up to 44 divisions (including seven panzer), would attack through the thinly defended Ardennes, then strike north along the Somme valley toward the Channel coast, cutting off the French and British forces lured into Belgium.

Despite mounting intelligence that the Germans were concentrating more heavily opposite the Ardennes area, Gamelin stuck with his plan for a rapid movement of his left wing into Belgium, and this was to play perfectly into the enemy’s hands.

Colonel Hans Oster, an Abwehr officer and ardent anti-Nazi, gave the Dutch military attaché, Major Gijsbertus Sas, in Berlin advance warning of the attack in the West on the night of May 9. Sas had already received a string of alerts since November from this source.

However, during that time, the Dutch commander-in-chief, General Izaak Reynders, questioned such intelligence, concluding that the string of alerts from Sas amounted to “B.S.” and did not “believe a bloody word of it.” Nevertheless, his warning of the German invasion of Norway proved correct. Reynders resigned after a disagreement with the Dutch defense minister; he was replaced by General Henri Winkelman, who kept Sas in place.

At 3 am on May 10, the Dutch at last accepted the warning and began to blow the bridges over the River Maas. Half an hour later, most of the airfields in Holland were bombed by the Luftwaffe; the small Dutch Air Force was destroyed.

The German 7th Airborne Division was deployed to capture The Hague and Rotterdam; 4,000 paratroops and 12,000 airborne infantry were delivered in Junkers Ju 52 transport planes but suffered heavy casualties and failed to capture The Hague. Attempts to capture the Dutch airfields at Valkenburg, Ockenburg, and Ypenburg also failed. At Ypenburg, many Ju 52s were shot up on the ground—some by RAF Hurricane fighters that intervened at 5 pm.

Army Group B had better luck. It pierced the Belgian frontier defenses on the first day when the principal fortress of Eben Emael, which was regarded as a formidable piece of engineering, fell to a special unit of the Koch Assault Detachment. The Germans landed by glider on the roof of the fortress at first light and, using hollow charges, kept the garrison cowed while paratroops and glider troops captured key Albert Canal bridges.

The fortress held out until the next day when the 223rd Infantry Division took the fortifications; the Koch unit lost six dead and 20 wounded. It was a brilliant coup de main, compared by many to the German capture of Douaumont at Verdun in 1916.

One of von Bock’s Army Group B armored divisions was deployed in southern Holland to link up with the airborne attack while the other two––the 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions––once across the Albert Canal, pushed southwest toward the Gembloux Gap, south of Brussels.

The German attack activated the Allied advance into Belgium under the Dyle Plan, the Belgians asking for assistance at 6:50 am. To cover the advance of the First French Army, General Rene-Jacques Prioux’s two mechanized corps moved over the frontier at noon toward the Gembloux Gap while General John Gort moved the British Expeditionary Force about the same time on the Wavre-Louvain line.

The British troops moved through Belgium, receiving a warm welcome from the local population. Captain Nick Hallett of 2nd Battalion, Royal Norfolk Regiment wrote on crossing the frontier, “I felt very excited as this was what we had been waiting for since the beginning of the war.” He expected to be bombed but, “Actually we saw no enemy aircraft all day.” This was a deliberate ploy by the Germans; they required a swift Allied move into Belgium and were not about to interfere with it.

The BEF was small compared to its French Allies and German enemy. It consisted of 10 infantry divisions, five Regular and five Territorial. All 10 were intended to be motorized, but there was a shortage of transport in some units to carry all the troops’ supplies and equipment.

The BEF had three tank brigades: two equipped with light tanks and one with Matilda heavy tanks. The force suffered from a lack of training that had not been fully addressed in the “Phoney War” period, and the Territorials lacked experienced officers and NCOs. The army had suffered long years of neglect, with priority in spending going to the navy and air force. Only in 1939 had the British government begun addressing the problems and equipment deficiencies.

Army Group A’s spearhead was led by General Ewald von Kleist’s Panzer Group, composed of three panzer corps. These armored columns were more than a 100 miles deep, their rear elements still east of the Rhine when they began to move. At 4:30 am on May 10, elements of the 1st Panzer Division crossed the Sauer River and entered Luxembourg. It was one of three under the command of General Heinz Guderian, the best armored commander on either side; he hoped to reach the Meuse at Sedan, 85 miles away, in three days.

On the right flank were the 5th and 7th Panzer Divisions, their initial objective being the Meuse. Luckily for the Germans, these densely packed formations on the narrow winding forest roads met little serious opposition.

The Belgian Chasseurs Ardennais, who had mined and barricaded the forest roads, were withdrawn to Namur on the 10th. The 1st Panzer Division crossing into Belgium at Martelange did run into resistance from the 4th Company of the Chasseurs Ardennais and met more delays and fierce resistance at Bodange from the 5th Company; it was held up for eight hours.

The French high command had estimated it would take an enemy force 10 days to reach the River Meuse through the Ardennes; in fact, it took the Germans two; 1st Panzer arrived at the river at 2 pm on May 12. The French had detected armor in the Ardennes, but they were more concerned with Army Group B to the north.

The only major problem for the Germans was traffic jams, which made the long, snaking columns vulnerable to air attack. One 1st Panzer Division officer recalled their anxiety: “Again and again, I looked with anxious eyes at the beaming blue sky, for what a target the division offers as long as it is compelled to progress by moving slowly forward along a single road. But not once does one French observation plane appear.”

By the evening of May 12, the leading German armored divisions of Army Group A had reached the Meuse in two places: Sedan on the east bank had been captured by Guderian’s corps, while Erwin Rommel’s 7th Panzer Division had reached Dinant.

However, it was German infantry and assault engineers with massive Luftwaffe support—more than 700 aircraft were committed—who made the crossing and breakout possible, not the armor. The first of Guderian’s tanks to cross the Meuse—temporarily held up by the French 102nd Fortress Division––did so at 2 am on May 14.

Rommel’s 7th Panzer attempted to cross the Meuse at 4 pm on May 12 at Dinant. Four tanks were rushed forward to secure the bridge before it was blown. Michael Berthold, driver of one of the Czech-built light tanks, drove through the cobbled streets of Dinant toward the bridge. He said, “As we drove through the main shopping street in Dinant, we were shot at from a butcher’s shop on our left by an antitank gun.

“The shell made a hole in the tank, and hit Steffan [the tank section commander] in his throat, severing his jugular vein. I only discovered that later, after I had driven the tank to safety. At the time I only knew he had been wounded because I felt him fall back on my neck. Our gunner was also wounded. His head was split open.

“I could only hear what was going on behind me since it was so noisy. I just carried on driving toward the bridge, not realizing that some of the tanks behind me had also been shot up. I got to within 10 yards of the bridge before it exploded.”

Meanwhile, the Allied advance into Belgium against Army Group B has been compared to the charge of the bull against the matador’s cloak, and as the bull passes he is struck in the flank. The BEF moved up to the Dyle Line on May 1, the only confrontation in its sector coming when the leading elements of the 2nd Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, 3rd Division was fired on by Belgian infantry near Louvain. Then there developed an argument over who was supposed to defend the town.

Major General Bernard Montgomery, 3rd Division commander, smoothed things over by placing himself under the Belgian divisional commander’s orders. However, as German pressure increased, the Belgians retreated and Montgomery was left in position and glad to see the back of his Allies.

The Allied high command assumed the Belgian defense of the frontier and delaying actions of the BEF and French Ninth Army would give them time to complete their move to the Dyle Line; however, some units were engaged before they were established.

To the right of the BEF, General Georges Maurice Jean Blanchard’s French 1st Army, heading for the Gembloux Gap, was in a worse position. It was confronted with masses of Belgian refugees heading for France, slowing its advance.

General René Prioux’s Cavalry Corps’ 2nd and 3rd Light Mechanized Armored, with 350 tanks in the lead, found the Belgians had not fortified the area. Prioux advised Blanchard that they should establish the defense on the Escout, 45 miles back. Blanchard agreed but in turn was overruled by General Gaston Billotte; Prioux would have to hold on while 1st Army rushed to support him.

On May 12, Prioux’s tanks encountered the panzers of General Erich Hoepner’s XVI Corps, and the armored clash took place near the town of Hannut. The French Somua tanks came as a shock to the Germans, for they were superior to the Panzer III and totally outclassed the Panzer Is and Panzer IIs. However, the French armor lacked air support.

A tank driver, Jean-Marie de Beaucorps, described a Stuka attack on his unit on May 12, shortly after a tank battle near Thisres: “A mournful sound, a long scream combined with the growling sound of their motors. I feel they are going to dive on my head. And then there are explosions that make one believe that the whole world is being thrown into the air. Our tank is thrown on its side; I think we are going to topple over. I panic and turn off the motor. We fall down on our tracks again. There is silence.

“Then, some way away from me, powerful explosions are to be heard: the ammunition lorry which has just supplied us is lying on its side and the ammunition is exploding. Twenty meters away from us, one of our tanks has turned over and has come to rest on its turret. The Lieutenant shouts, ‘Get going, goddammit, full speed ahead!’”

Captain Ernst von Jugenfeld, who commanded a tank company in the 4th Panzer Division, felt May 12 was “hard and bloody” and a “large number of our tanks were lost.”

The battles around the Gembloux Gap continued until the evening of May 14, when the French armor retreated behind its infantry line running from Wavre to Namur, by which time more than 100 French tanks were out of action; losses in the 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions were as high.

The situation in Holland deteriorated rapidly; German airborne troops and the 9th Panzer Division were approaching Rotterdam. Giroud’s French Seventh Army ran into 9th Panzer at Tilburg, recoiled, and failed to link up with the Dutch. After the bombing of Rotterdam, the Dutch capitulated on May 15.

However, the crucial area was to the southeast along a 50-mile stretch of the Meuse Valley. Here, from May 13-15, the fate of France was decided. The Germans had advantages and had enjoyed more than their share of good luck. They had achieved surprise by quickly striking through the Ardennes. They had encountered little opposition and no interference by the Allied air forces. They enjoyed air supremacy, and their strike pitted the best and most mobile units in the German Army against two of the weaker French armies, which lacked antitank and antiaircraft guns. Five German panzer divisions were thus striking the junction of the French armies.

But the French position was not yet hopeless. The River Meuse, an average of 60 meters wide and fast flowing, was a strong natural position. The western banks were steeply wooded and ideal for defense. Just north of Houx, opposite Rommel’s division, were the heights of Wastia, commanding the river line. At Montherme, Hans-Georg Reinhardt’s XXXXI Panzer Corps faced 1,000-foot heights.

At Sedan, again the west bank was steep, and the French had constructed concrete bunkers every 500 meters, backed by barbed wire and field defenses. Also, the bulk of Army Group A was still tramping on foot through the Ardennes.

On the night of May 12, General Georges reported to Gamelin, “Defense now seems well assured on the whole front of the river.” He was wrong and did not learn until 9 am on May 13 that the Germans were across the river in two places on the front of General Andre-Georges Corap’s Ninth Army. The rigid French command structure was proving slow to adapt; only at the end of the day did unsupported tanks attack and capture a few prisoners, then withdrew.

After dark on May 12, Rommel’s motorcycle battalion at Dinant discovered an unguarded footbridge over a weir and crossed the river, establishing a bridgehead. They were armed only with light infantry weapons, and their hold was tenuous. As dawn broke on May 13, defensive fire on the footbridge was heavy, but the German battalion commander managed to get most of his men across and pushed on toward the heights.

Meanwhile, the 10th Panzer Division on the corps’ left was in a bad a spot. A hurricane of fire from the defenders shot up the boats trying to cross, but heroic groups of assault engineers did get across, knocking out bunkers and clearing a path for two infantry battalions to cross on the 13th.

It was the success of 1st Panzer Division and its infantry under Lt. Col. Hermann Balck that saved the day. Having identified a place the French had abandoned during the air raids, two of his battalions crossed the Meuse and soon rolled up the line of bunkers, penetrating three miles toward the town of Cheveuges by 10 pm on the 13th. The infantry advance allowed 2nd Panzer to start crossing the river on pontoon bridges late that night. The French needed to deliver a massive counterattack on the 14th or face disaster.

The French 55th Division had two infantry regiments and two battalions of light tanks available on the 13th, but they were not committed until the morning of the 14th against Balck’s lightly armed men. Although enjoying some success, they soon ran into panzers that had been streaming over the pontoon bridges for hours and were pushed back. Panic began to infect the 55th Division when rumors began to spread of a massive German breakthrough. This rapidly spread to the 71st Division; by 2 pm on the 14th the French defense at Sedan had collapsed.

South of Houx, 7th Panzer was also trying to cross the Meuse near the village of Bouvignes using rubber assault boats. The 6th Rifle Regiment had managed to get a company across the river, but with daylight more attempts to cross failed. When Rommel arrived, he found that the crossing had stalled altogether. He ordered some nearby houses set on fire to provide a smoke screen and brought some tanks to the riverbank to hit French bunkers on the opposite bank.

A cable ferry using pontoons was constructed. Rommel himself crossed the river, urging the infantry to higher ground. Returning to the east bank, he traveled north to Houx, where engineers had constructed a pontoon bridge. Yet, by the morning of May 14, only 15 panzers were across and the bridgehead on the west bank was precarious.

On the 14th, on the high ground north of Houx, Rommel struck west with a force of about 30 tanks aiming for the town of Onhaye. He was nearly killed when his tank crashed, sliding down a steep bank and ending up on its side. Then he was nearly captured by advancing units of a North African infantry division moving up to contain the threat.

This was the best division in the Ninth Army and, if used correctly that day, might well have smashed the bridgehead. Had it been used with the 1st Armored Division moving from the south, 7th Panzer would have been in serious trouble. However, both units had been held too far from the river line and had not been ordered to move quickly enough.

Lack of control through poor communications left many French units feeling isolated, and then rumor and panic gripped some. To the south, the French 22nd Division, under no real pressure, began to retreat. This convinced Corap at midday on May 15 that he must withdraw from the Meuse. General Gaston Billotte, his superior, agreed the move was needed to stay on balance. However, both underestimated the new speed of mobile warfare and how such a move would lead to the disintegration of their forces.

To the south at Sedan the situation was no better for the French Second Army. Once again it held a formidable position. Bunkers had been built on the western bank of the river while behind them the ground rose steeply to the Marfee Heights, giving the defenders excellent fields of fire from this natural gun platform toward the Germans panzers crowded on the east bank of the Meuse. However, the French guns were rationed to 30 rounds per gun by the corps commander, General Charles Grandsard, who believed he faced a long battle.

The German artillery was in a worse position, short of heavy guns and ammunition. Even Heinz Guderian wanted the attack delayed until the artillery support, still plodding along the roads of the Ardennes, reached them. Von Kleist, his superior, was determined to attack, and the Germans did have the support of 710 aircraft. The heavy air attacks, although not causing crippling casualties, did disrupt the defenders. Many telephone cables were cut, leaving blockhouses isolated, while German fighters swooped down on any movement.

Despite the air attacks, crossing the Meuse was difficult. The 2nd Panzer Division on the right, near the village of Donchery, got a few men across, but fierce resistance killed or wounded almost all of them. Tanks tried to knock out the bunkers by firing across the river, but only when the bunkers were attacked from the rear by the 1st Panzer Division did the 2nd manage to cross the Meuse.

At last, however, the Allied high command was beginning to react. The air forces threw 400 aircraft into the battle to try and destroy the Meuse bridges. The RAF’s single-engine light bombers, known as Fairey Battles, suffered heavy losses from German fighters and flak batteries covering the crossing places. Of 71 bombers taking part, 40 were shot down; 31 fighters were lost.

The official RAF history records, “No higher rate of loss has ever been experienced by the Royal Air Force.” No crucial damage was inflicted on the pontoon bridges, and tanks and equipment continued to cross.

The French had no other option but to seal the growing gap in their defenses between Dinant and Sedan. The 3rd Armored Division was concentrated south of Sedan along with the 3rd Motorized Division under Maj. Gen. Jean Flavigny. He wished to attack on the 14th but then changed his mind after a heated argument with General Antoine Brocard, 3rd Armored commander, who told him his unit needed resupplying. Instead, it was deployed in a static defense role to plug a 12-mile gap.

The fate of the 2nd Armored Division was even worse. The wheeled vehicles of this unit advanced toward the front by road while the tracked vehicles went by rail. General Georges, impatient with the slow rate of rail movement, ordered the tanks unloaded at Hison, which lay directly in the path of the panzer advance. On May 15, the wheeled vehicles were cut off from the tanks, and in effect the division ceased to exist as a fighting formation.

By the evening of May 15, the Germans held a decisive advantage. Guderian, recognizing the French on his front were disintegrating, swung the 1st and 2nd Panzer Divisions westward with orders to advance toward Rethel on the Aisne, 30 miles from Sedan.

While 10th Panzer and the Grossdeutschland Regiment thrust toward Stoone, south of Sedan, against Flavigny’s 3rd Motorized Division, with orders to keep the breach open until relieved by the slowly advancing infantry, Guderian was taking a risk. As 10th Panzer was not fully deployed across the Meuse, he admitted, “The success of our attack struck me almost as a miracle.”

Grossdeutschland attacked Stoone at 7 am on May 15; by luck this forestalled Flavigny’s attack planned for 3 pm. By 11 am, the French had regained Stoone and pushed back the worn-out German infantry. Panzergrenadiers from 10th Panzer retook the village but were forced out again by 5 pm.

However, General Brocard’s 3rd Armored strength had been used piecemeal. Even worse, two tank battalions had not even gotten into action, yet 10th Panzer and Grossdeutschland had been fully committed. When Brocard called off the attack on the evening of May 15, the battle for France was lost.

Guderian’s 1st and 2nd Panzers were held up at Chagny by elements of the French 14th Infantry Division, then again at the villages of Bouvellemert and La Hargne, where a North African brigade of cavalry fought until wiped out.

Guderian recalled in his memoirs that Lt. Col. Balck was again leading the attack: “The men in the front line were falling asleep in their slit trenches. Balck himself … told me that the capture of the village had only succeeded because, when his officers complained against continuation of the attack, he had replied, ‘In that case, I’ll take the place on my own,’ and had moved off. His men had thereupon followed him.”

By nightfall on May 15, a huge bulge had developed in the French line that cut off the French 1st Army and BEF in Belgium from the rest of the French forces to the south. There was virtually nothing to stop seven panzer divisions from heading west to the Channel.

On May 15, General Billotte, commanding the Allied forces in Belgium, ordered a phased withdrawal through three river lines on the Senne, Dendre, and Escaut Rivers, a distance of 50 miles, with an active enemy to the front and the danger of being cut off to the rear. It was a difficult undertaking.

Lieutenant General Alan Brooke, who commanded the BEF’s II Corps, wrote of the strain of command: “I was too tired to write last night and now can barely remember what happened yesterday. The hours are so crowded and follow so fast on each other that life becomes a blur and fails to cut a groove in one’s memory.”

On May 19, the RAF component of the BEF was withdrawn from France to southern England; only 66 of the 261 fighter aircraft made it back. However, most of the ground crews and pilots returned, even if 120 damaged but repairable Hawker Hurricane fighters were abandoned in France.

Men of the BEF marched back, exhausted, suffering from blisters, at times virtually sleep walking. Marching in threes with arms linked, the man in the middle could sleep a little. There were numerous accidents as drivers fell asleep at the wheel. Plus, they were frequently under air attack from German fighters. It had been only six days since they had advanced from the French frontier, but now they were retreating, and many men were bewildered. The roads were also choked with a mass of refugees of all ages; near Tournai, a mobile circus was caught in the chaos, complete with terrified elephants.

By May 19, the BEF had managed the retreat to the River Escaut, and now seven divisions faced von Bock’s advancing troops. Behind them to the south, the panzers were still a threat, and Billotte had no answer for this.

General John Gort, the British commander, now began to consider a further withdrawal and evacuation from Dunkirk. The War Office in London still hoped for a breakout to the south and a linkup with the French. In a meeting with Billotte on the 18th, Gort said nothing about a retreat to the Channel ports. However, Gort had warned the general staff of his thoughts, and that same day the Admiralty was consulted about an evacuation, which was code named Dynamo.

With great reluctance, on May 20 Prime Minister Winston Churchill issued the following order: “As a precautionary measure, the Admiralty should assemble a large number of small vessels in readiness to proceed to the ports and inlets on the French coast.”

Churchill also sent General Edmund “Tiny” Ironside, a 6-foot, 4-inch giant, from the general staff to Gort to assess the situation and to impress on him the need to break out to the south. All he could offer was a limited offensive by two reserve divisions from Arras.

On May 21, the British attacked with just two tank battalions and two infantry regiments supported by part of the French 3rd Light Mechanized Division (70 tanks), which caught Rommel’s 7th Panzer by surprise and for a few hours created havoc. Von Rundstedt wrote, “For a short time it was feared that our armored divisions would be cut off before the infantry divisions could come up to support them.”

The Germans (including Hitler) had begun to show concern over the speed of their advance and had already put the brakes on the panzers. Also, the imbalance between the two army groups was a problem; Army Group B now had only 21 divisions, whereas Army Group A had more than 70, plus all 10 armored divisions. On May 17, Guderian was halted for 24 hours, although he was allowed to continue a “reconnaissance in force.”

But on May 24, the panzers were ordered to halt for two crucial days. The German decision was influenced by the French counterattack of May 22, which should have gone in with the British south of Arras. It struck the German 32nd Infantry Division a heavy blow. Only the formidable 88mm antiaircraft guns used in the antitank role finally stopped the French drive.

Guderian was furious with the order to halt: “We were utterly speechless. But since we were not informed of the reason for this order, it was difficult to argue against it. The panzer divisions were therefore instructed: ‘Hold the line of the canal. Make use of this period of rest for general recuperation.’”

Before the halt order, elements of the 2nd Panzer Division, having covered 60 miles that day, reached the Atlantic coast at Noyelles. The BEF and French forces to the north were cut off.

The delays forced on the panzers on May 21 due to exhaustion and May 24 from the high command allowed the Allies to prepare Calais, Boulogne, and Dunkirk for evacuation; General Douglas Brownrugg had already sent the Rear GHQ to Boulogne. The French were not told of this move, which did not aid the declining relationship between the Allies.

French forces evacuated the town on May 21, while two British Guards battalions were sent to France on cross-Channel ferries, arriving on the 22nd. The port area had been bombed heavily, and the troops found a French oil tanker burning near the entrance to the harbor.

The Irish Guards were first ashore. Brigadier William Fox-Pitt with his two battalions and some 1,500 troops of the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps had the mission of holding an eight-mile perimeter against a German panzer division. RAF light bombers flying from southern England and a heroic defense by elements of the French 21st Division managed to slow down 2nd Panzer.

Sergeant Arthur Evans of the Irish Guards’ antitank platoon sighted the first approaching panzers: “I could clearly see the tank commander’s head above the open turret with his field glasses to his eyes. We opened fire and the tank rocked as we scored two direct hits. The crew bailed out and abandoned it. Soon a second appeared and that, too, was effectively disposed of.”

The fighting continued late into the night. Early the next day, the Germans attacked again; the Guards were forced back toward the port area. By afternoon the German attack was stalled and coming under the effective fire of Allied destroyers. HMS Whitstead was in the harbor evacuating troops while giving close gunfire support. Whitstead pulled out fully loaded, her place taken by HMS Keith and Vimy.

Guderian had been pleading for Luftwaffe support but, such had been the speed of the German advance, it was in the throes of rebasing farther west. It was not until 7:30 pm that the Luftwaffe attacked with 60 aircraft. A French destroyer was sunk, but a dozen Spitfires arrived at the same time.

The ships loading in the harbor survived any major damage. Throughout the night the destroyers continued lifting off men. With the Guards battalions the last to leave, those evacuated from Boulogne amounted to 4,368. Part of 3rd Company of the Welsh Guards failed to get the order to retreat and was captured after a heroic last stand, finally surrendering on May 25.

Things did not go so well at Calais. The harbor was more difficult to use, and only 440 men were evacuated on May 27.

Gort abandoned the attempt to break out to the south by ordering a retreat to Dunkirk. On May 26, the British government reached the same conclusion, instructing him on the same night [the] “safety of the BEF will be [your] predominant consideration.”

The halting of the panzers gave Gort time to form a new defensive line. Even so, the BEF was in peril; more than 300,000 troops were strung out along a 60-mile corridor, with superior enemy forces to the north and south. The supply system was beginning to fail, and the Belgian Army gave up the fight on May 28, which released more of von Bock’s men.

However, during this period the BEF would put on its best performance. On the northern flank Maj. Gen. Harold Franklyn’s understrength 5th Division put up a spirited defense aided by extensive artillery support, which fired 5,000 rounds in 36 hours. Franklyn even launched limited counterattacks, keeping the enemy off balance. On the night of May 28-29, Franklyn disengaged, retreating through a new defensive line held by the 3rd and 4th Divisions.

On the southern flank, a defensive position was formed on the La Bassee-Gravelines Canal line. Maj. Gen. Noel Irwin’s 2nd Division was to hold the line; opposing it were four panzer divisions and two motorised SS infantry divisions.

The German halt order was eventually lifted, and Irwin’s 2nd Division then came under infantry attack supported by artillery. In La Bassee, the 1st Queens Own Cameron Highlanders, at the extreme end of the line, held out for two days; only 79 of the battalion would make it back to Britain. North and west, the 2nd Royal Norfolks held the line until the 27th. Part of the battalion surrendered to the SS Totenkopf Division, but many were massacred.

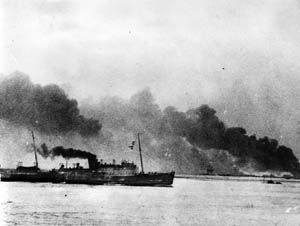

As von Rundstedt’s Army Group A pushed north, fighting every inch of the way, the British slowly pulled back to the Dunkirk perimeter in a remarkable fighting retreat. But the evacuation from Dunkirk presented several problems.

Its miles of sandy beaches had advantages but were not ideal. The harbor area of Dunkirk had been heavily bombed and was largely out of action, but there were two old wooden jetties stretching out into the sea that could be used. There were strong tidal currents and because of sand banks a direct approach other than by shallow-draft vessels was not possible. However, the Royal Navy had the skill to overcome these problems.

On May 14, the Admiralty had requested all boats from 30 to 100 feet long to be registered; on the 19th it began planning the evacuation. In command was Vice Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsey stationed at Dover. All sorts of vessels were pressed into service, from passenger ferries to shallow-draft Dutch craft that had escaped to England.

Most valuable to the operation were the destroyers of the Royal Navy. They were fast, had some antiaircraft protection, and could carry around 600 soldiers per lift. But they were in short supply, and the crews were already exhausted from their efforts at Boulogne and Calais. On the evening of Sunday the 26th, Ramsey received the signal to start Operation Dynamo. Prior to this some 27,000 men, largely wounded and noncombatants, had been evacuated.

On May 27, the RAF began an immense effort to keep the Luftwaffe away from the evacuation area. Fighter Command deployed 16 squadrons and on the first day flew 287 sorties. Some troops returning from Dunkirk claimed the RAF was not there. British fighters may not have been seen, but they shot down 132 German aircraft over the area.

Captain William Tennant, with a staff of 150, arrived at Dunkirk on May 29 to take charge of the embarkation; the scene was chaos. Most of the troops there were ill-disciplined rear units and deserters. Just 7,669 men were taken off that day.

Having surveyed the two moles, large stone structures used as piers, breakwaters, or causeways, Tennant decided the east one could be used. A passenger steamer tied up there and loaded 950 men in an hour. Ramsey was reinforced with an antiaircraft cruiser and a large increase in destroyers; he now had 30 available. The weather was kind, with low clouds; burning oil tanks laid an effective smoke screen over the loading area.

On the 29th, the pace of evacuation accelerated, and 47,000 men were taken off. However, about midday the weather cleared, and German aircraft inflicted heavy damage. Two destroyers were sunk by an E-boat and a U-boat, and another destroyer, the Grenade, was sunk while loading at the jetty. Full of troops, she took a direct hit but luckily was towed away before her magazines exploded. The large steamer Clan Macalister was hit by Stukas and had to be abandoned; 11 naval vessels were lost that day.

Ramsey decided to withdraw some of the modern destroyers. He also formed the wrong impression that the mole and outer harbor could no longer be used, so loading there was stopped. On the 30th, the mistake was rectified.

Engineers constructed two piers of trucks driven out into the sea and decked with planks, which speeded up the process of embarking men into smaller craft that were ferried out to the larger vessels. On the 30th, 29,512 more men were lifted from the beaches and 24,311 from the harbor. Two destroyers, HMS Wolsey and HMS Sabre, lifted off record totals of men, with Wolsey making three trips with 1,677 men and Sabre taking 1,700 in just two crossings. Shipping losses were minimal.

The western end of the beachhead was held by the French, the rest by the British. By the 30th, most of the BEF had reached the refuge of the Dunkirk perimeter, which was shrinking and coming under increasing pressure. Late that day the eastern end of the perimeter troops began pulling back to the beaches. Some 6,000 British troops remained behind, holding the eastern outskirts; the rest of the perimeter was now held by the French, who put up a final heroic defense.

The next evening Rear Admiral William Wake-Walker, who commanded the shipping of Dunkirk, witnessed a remarkable sight that lifted his spirits: “I saw for the first time that strange procession of craft of all kinds that has become famous. Tugs towing dinghies, lifeboats and all manner of pulling boats, small motor yachts, drifters, Dutch schoots [schuits], Thames barges, fishing boats, and pleasure steamers” were sent to rescue the beleaguered BEF.

Tension between the two Allies mounted. The British felt they had been let down by French incompetence, while the French considered the British untrustworthy. The refusal to send more RAF fighters into the battle was a sore point. The Dunkirk evacuation was merely leaving France to her fate.

On May 31, a total of 64,429 men were lifted off, the biggest total for a single day. Churchill flew to France on the 31st for a crisis meeting and promised the withdrawal would be on equal terms and the British would form part of the rear guard.

During the first three days of June, it was mainly French troops that were lifted off. June 1 saw 64,429 evacuated, with 79,177 evacuated over the next three days.

The heroic story of hundreds of little boats crewed by stoic civilians from all walks of life crossing the Channel to rescue the BEF has become legend. Most of the craft were crewed by the Royal Navy and Royal Navy Reserve; however, many civilians volunteered and risked—and some lost—their lives to save the troops.

Squadron Leader C.G. Lott recalled the scene below as he flew top cover on June 1: “Big boats, little boats, boats with brass funnels, boats with strings of smaller boats strung out behind them like a duck with her ducklings. In a never-ending stream they crept over the water in both directions. The slowness of their movement was anguishing. Their vulnerability to air attack was so obvious as to make the whole spectacle truly heroic, and I could both have cheered and wept as I watched.”

But the Navy paid a heavy price, even though the First Sea Lord had reversed the decision and sent the more modern destroyers back in on June 1. Thirteen British warships were sunk by the end of that day, and only nine of the original 41 destroyers were undamaged. Captain Tennant watched HMS Worcester leave that day, her decks awash with debris and blood and under constant attack. He signalled Ramsey recommending that daylight operations be ended.

During the night of June 2, the final British troops—the 1st Kings Shropshire Light Infantry—were evacuated on the Channel ferry St. Helier. At 11:30 pm, Tennant signalled Ramsey: “BEF evacuated.” Then he and General Harold Alexander toured the harbor and beaches in a launch. Using a megaphone, Alexander shouted many times, “Is anyone there?” Satisfied that no one remained, they boarded a destroyer and left.

Originally, the Admiralty thought about 45,000 troops might be rescued; in the end 224,686 members of the BEF and 141,445 Allied troops, mainly French, made it to the England. Operation Dynamo had proved a huge success.

In a speech to the House of Commons on June 4, Churchill told the country, “We must be very careful not to assign to this deliverance the attributes of a victory. Wars are not won by evacuations.”

The position France faced on June 5 was a “strategic nightmare.” Its army had lost the best part of 30 divisions—a third of its strength, and most of its armored units. Twelve British divisions had gone; two remained. General Maxim Weygand, now in command, was prepared to fight on. However, as early as May 28, he had abandoned hope of defending the Somme line. He advised his government that once the defense was breached they should seek an armistice.

By June 8, the Battle of the Somme was lost. Both French flanks had been turned, and Weygand ordered a withdrawal to the south. The French government abandoned Paris on June 10 for Tours on the Loire.

The French defeat involved Britain in a second evacuation. General Alan Brooke was sent back to command the remaining British troops that Churchill hoped to reinforce with two new divisions. However, on June 12, the 51st Highland Division was forced to surrender to Rommel on the Normandy coast, and on the 14th Brooke decided to withdraw his remaining troops. Churchill was reluctant to leave France to fight on alone, but after a heated argument he finally agreed.

In the second evacuation, 144,171 British troops were lifted off, this time along with much of their equipment. Several thousand Allied troops were also taken off from Nantes/St.Nazaire and Cherbourg. The liner Lancastria was hit by bombs on June 17; nearly 2,500 were rescued but 3,000 more drowned. It was a loss kept from the British public. Brooke himself reached Plymouth on June 19. On the 22nd, the French unconditionally surrendered at Compiegne.

For Germany it was a remarkable victory decided largely in the first five days of the campaign. In the summer of 1940 Guderian thought the best way to force Britain out of the war was to thrust south against her Mediterranean bases through Spain. However, this opportunity was missed, which led to Hitler fighting on two fronts and to total defeat.

The UK-based author dedicates this article to the memory of his uncle, Battery Quartermaster Sergeant Wilfred Lane, who served in the 152nd Battery, 51st Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery, a Territorial Army unit. He was killed in the retreat to Dunkirk between May 27 and June 2, 1940. He has no known grave but is remembered with honor on the Dunkirk Memorial, Column 7.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments