By Kevin M. Hymel

Private First Class Irving Bromberg saw a huge puff of smoke erupt from the German tank’s cannon muzzle as it headed straight for his M4 Sherman tank. The round streaked past and missed.

Bromberg sat next to the driver in the bow gunner’s seat manning a .30-caliber machine gun. His turret gunner fired the tank’s 75mm cannon, also missing, but the American cannon had an advantage: an automatic breech-loader. The spent shell quickly popped out of the breech and the loader shoved in another round. The gunner fired a second round before the German could reload. The second round blasted the enemy tank.

The Americans kept firing. The loader called for more shells, and Bromberg passed them up. The German tank stopped but it did not catch fire. Then its crew bolted out of its hatches. “Get them!” the gunner shouted to Bromberg, who squeezed his machine gun’s trigger and sprayed fire into the enemy, killing them. Bromberg’s tank sped off. The brief tank battle in the Tunisian desert in the spring of 1943 was Bromberg’s first.

Although Bromberg wore the triangular 2nd Armored Division shoulder patch, he was serving as a replacement with the 1st Armored Division, which had taken heavy casualties during the six-day Battle of Kasserine Pass in late February.

After the mauling, the division went back on the offensive, pushing the Germans east. So desperate was the division for replacements that Bromberg did not know the rest of his crew. “I didn’t even know where I was,” he admitted.

As the bow gunner, Bromberg often switched positions with the driver to give him a rest. When not in battle, Bromberg kept his head out of the hatch, but when ordered to “button up” he closed the hatch and peered through a periscope. “I remember it had pretty wide vision,” he recalled. “It was good.”

Besides the driver and the bow gunner, the Sherman also had a commander, gunner, and loader, all three of whom worked in the turret. Shells were kept in the turret, but during battle, Bromberg would pass up extra rounds stored behind him.

All five men were relatively close in the tank, but the noise generated by the engine, treads, and the battle outside required them to wear microphones and headsets to communicate. The cannon could be noisy, but it was actually the .30-caliber machine gun in the turret that bothered Bromberg the most. When fired by use of a foot pedal—often to help aim the cannon—the entire turret vibrated. “That was the most nerve wracking,” recalled Bromberg.

The main gun, the 75mm, sufficiently matched the German Army’s main battle tank, the Panzerkampfwagen IV, commonly known as the Panzer IV, which also mounted a 75. The tanks were almost equal in weight, height, and armor protection. It was the heavy Tiger tank, which made its first appearance in North Africa, and later the Panther, that would outclass the Sherman on the battlefield.

Nineteen-year-old Irving Bromberg from Columbus, Ohio, had joined the Army in April 1942, although he had tried to serve his country earlier. When he heard over the radio that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor, he went to his local post office to join the Marine Corps, only to be rejected for having flat feet. An officer encouraged him to join the Navy, but instead Bromberg eventually enlisted into the Army at nearby Fort Hayes.

Bromberg was sworn in at Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, and issued a uniform. He soon shipped out to Fort Knox, Kentucky, for three months of tank training.

He learned every position inside the light M3 Stuart tank and the larger M3 Lee and M4 Sherman. By the time the United States entered the war, the Stuart was already obsolete. With its thin armor and puny 37mm main gun, it would be relegated to the role of scout tank.

The Lee, a stopgap creation to fill the void while the Sherman was developed, housed its main gun, a 75mm, in a sponson built into the hull while the turret wielded a 37mm gun. Most Lees saw action with British and Russian forces.

The Sherman and its variants, with a turret-mounted 75mm gun, and later a 76mm cannon, would serve as America’s main battle tank throughout the war. Driving the three different tanks, Bromberg learned a skill not used in automobile driving: double clutching, quickly gearing down from fourth, third, second, and first gear before using the brake. After the war, it would prove a hard habit to break.

Bromberg joined the 2nd Armored Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and was assigned to the 2nd Platoon of Fox Company, 66th Armored Regiment of Combat Command A (the equivalent of an infantry regiment).

He soon befriended his fellow tankers. One night after some heavy drinking in a Fayetteville bar with one of his sergeants, he walked into the middle of the street and urinated. Military policemen spotted him and were preparing to take him to the local police station when his sergeant ran out shouting, “You can’t take him—I’m his sergeant!” So the MPs released Bromberg and arrested the sergeant.

Bromberg waited at the station for the sergeant’s release until the police threatened to arrest him. With no other options, he returned to Bragg. The sergeant eventually returned and said if they were going to reduce his rank he would ask for a court martial. Bromberg agreed to confess to the company commander that the whole thing was his fault.

“I was so scared,” Bromberg said of speaking to his captain, who asked him why he had to urinate in the street. Not knowing any other answer, Bromberg told him, “When you gotta go, you gotta go.” His words must have worked; the sergeant kept his rank.

Their training complete, the tankers prepared to deploy overseas. Bromberg headed to New York, where he attended a speech by the 2nd Armored Division’s previous commander, who now commanded the American Army’s Western Task Force: Maj. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr.

The speech was typical Patton, filled with instruction and inspiration and peppered with foul language. “Every other word was a profanity,” recalled Bromberg, but he was not surprised. “I was just a kid, but in the Army profanity doesn’t come as a shock.” Nor was he in awe of his commander. “At the time, his name wasn’t what it is today.”

Patton’s Western Task Force was slated to attack French Morocco, just one offensive of the three-pronged attack on Vichy French North Africa, Operation Torch. Elements of the 2nd Armored Division, commanded then by Maj. Gen. Ernest N. Harmon, would spearhead the attack on November 8, 1942, but Bromberg would not be part of it. He finally made it to Casablanca in December, a month after the successful assault and three-day battle against the French.

Bromberg found Morocco quiet. The fighting was going on more than a thousand miles away in Tunisia, but the Luftwaffe constantly reminded the Americans they were in a war zone. On Christmas Eve 1942, Bromberg and his comrades were watching a movie when German bombers raided their camp. Searchlights pierced the sky, joining together when they found a bomber. Then tracer fire shot skyward.

“It was like watching a football game,” recalled Bromberg. “You had to feel sorry for those guys.” He did not see bombs impact anywhere, but he and his buddies got a good laugh the next morning when Axis Sally, the female Nazi propagandist, reported over the radio that the Luftwaffe had destroyed the 2nd Armored Division.

Assigned to the 1st Armored Division after the Kasserine debacle, Bromberg worried how he would react to combat, but as his tank approached the line of departure he was too busy to think about it. He spent the day loading and firing his machine gun at anything that moved and passing rounds up to the loader. “It was after the day [was over] that I got shook up,” explained Bromberg.

It was not long after Bromberg’s baptism of fire that he and his crew faced off against the German tank. “It’s not like the movies where they’re going 25 miles an hour,” he said. “We were doing three or four miles an hour.” Bromberg first thought the enemy tank was American. The missed shot told him otherwise.

While the Germans were busy ejecting their shell casings with a hand crank, his Sherman’s automatic breech loader made the difference. “That saved us,” he recalled. Until then Bromberg had not liked the breech loader. “It always scared me because I thought I would get my hand caught in it.”

Although Bromberg had been assigned to the 1st Armored for only a week, he had learned how to fight on a mechanized battlefield. For sleep, he would crawl beneath the tank or sleep in the tank. One morning, his tank pulled off the front, and an exhausted Bromberg climbed out and immediately fell asleep on the ground. “When I got up, there were two dead Germans next to me.”

He also grew wary of the local Tunisians, who continuously switched support between the Americans and the Axis. Whenever they visited Bromberg’s unit, the Americans could expect an enemy artillery barrage. “Some of our fellows shot them,” he said.

Bromberg could deal with enemy tanks and artillery barrages, but the one thing he truly feared was German airplanes, which attacked nightly. They dominated the sky. One of the German’s favorite tricks was to fly over the American lines and flick their lights in hopes that Americans would fire at them, revealing their positions. “That scared me the most of the whole war,” he said.

His stint at the front over, Bromberg returned to his unit and trained for the invasion of Sicily, slated for July 9, 1943. As part of Italy, Sicily would be the first chunk of Axis real estate attacked by the Western Allies. The newly created American Seventh Army, under Patton, would assault the Gela beaches. The 2nd Armored Division would support the 3rd Infantry Division near the town of Licata, but Bromberg would not be in a position to support anyone.

Heading to the shore in a Landing Ship, Tank (LST), Bromberg heard an enemy airplane drop a bomb. “The next thing I know, we’re hit,” he recalled. His buddy, a tanker named Pippard, grabbed Bromberg, and the two went over the side to a waiting DUKW—an amphibious truck. They made it to shore and promptly got lost. With no tank, the two men spent the next two weeks away from the war, surviving on lemons, cantaloupes, and whatever they could obtain from the locals.

When American trucks passed by they would yell, and the GIs would throw them rations. Technically Absent Without Leave (AWOL), the two men enjoyed themselves until the division sent a truck to the rear looking for stragglers. They climbed aboard, and when Bromberg reported to his captain, the officer merely asked him if he was okay.

Back in the war, Bromberg climbed into a tank for the drive on Palermo in northern Sicily. If Patton could take the port city, he would effectively cut the island in half and possess a staging area to attack Messina on the northeast corner of the island.

Bromberg found the fighting to Palermo surprisingly light. The Italian soldiers readily surrendered to the Americans. “Half we didn’t even take prisoner,” he said, and let the Italians go. At one roadblock, Italian soldiers stepped out onto the highway and warned Bromberg’s crew about a German antitank gun up ahead. “We didn’t go any farther.”

Bromberg’s tank entered Palermo on July 22 to the cheers of its citizens. “It was like a big parade,” he recalled. “They were giving us wine.” He got out of his tank and went into a house for a meal. Reaching Palermo capped off a two-week drive from the Gela beaches. The campaign would now turn east, but with the mountainous terrain blocking the way the 2nd Armored remained in Palermo with occupation duties. “Sicily was not too much fighting,” said Bromberg, “but good experience.”

The Sicily campaign ended on August 17, 1943, when Patton’s forces reached Messina hours before the British under General Bernard Law Montgomery. The invasion of Italy soon followed, but the armor support mission on the peninsula went to the 1st Armored Division.

As casualties mounted on the Continent, more and more tankers from Bromberg’s division were sent in as replacements, but he was not one of them. Instead, he and the rest of his division set sail for England and a new battlefield.

Bromberg arrived in England in November 1943 and trained with his unit for the coming invasion of France. He dreaded it, having seen war and knowing it was only a matter of time before he might be its next victim. He enjoyed England, a step up from the deserts of North Africa and the poverty of Sicily.

Feeling he had only weeks to live once he landed in France, he became fatalistic. He spent a two-week furlough in Manchester trying to forget the war through alcohol. “I didn’t care about anything,” he recalled. “I just carried on and drank and carried on.” Later, at a pub in London Bromberg passed out from drinking, and the patrons laid him on some barstools while they debated whether to take care of him or “Throw the Yank out!”

When it came to women, Bromberg’s company commander, Captain Curtis Clark, did not believe in American soldiers marrying foreigners and demanded the men get his permission before proposing to any girl. Bromberg frustrated Clark by proposing to every girl he dated. “I had a good time,” he said. Clark was soon promoted, and Fox Company received a new commander for the invasion of France: Captain William A. Nicholson.

June 6, 1944, D-Day, was mostly an infantrymen’s battle, with grunts fighting to open the draws on Omaha Beach and the causeways on Utah Beach with the help of independent tank battalions. Once the beaches were secured, armored divisions slowly joined the battle.

Bromberg’s tank rolled out of the belly of an LST and roared across Utah Beach on June 12, D+6. Hedgerows—five-foot-high earthen banks topped with trees and bushes—divided the Norman countryside and served as perfect defensive positions for the Germans. Every time the Americans broke through to a field surrounded by hedgerows, the Germans would simply fall back to the next set of hedgerows.

In the confused fighting, Bromberg often saw tanks burning beside him. “I was lucky,” he said about surviving the fight. He fired his machine gun at every bush or tree he saw. “I didn’t take any chances. Each hedgerow was a battlefield.”

The hedgerows initially proved a problem for American tankers. Rolling over the high banks exposed the tanks’ thin underbelly armor, which the Germans could penetrate with a Panzerfaust—a single-shot, shoulder-fired antitank weapon. Bromberg’s Fox Company entered the hedgerows with 17 tanks. They were soon reduced to four. “Our tanks were getting knocked out so fast,” he said.

Rank spared no one. On June 13, an enemy sniper killed Captain Nicholson. “He was so mature,” Bromberg recalled, who thought the commander was 30 or 40 years old. He later discovered Nicholson was only in his 20s. “He looked older.”

Lieutenant William H. Schwartz, the leader of Bromberg’s 2nd Platoon, temporarily took charge of the company until Captain Douglas J. Richardson took over.

Schwartz commanded Bromberg’s tank. “He was born for combat,” said Bromberg. “I didn’t like him as a person, but I knew if I stayed in his tank I’d stay alive.” Once Richardson took command, he called on 2nd Platoon for almost every mission, to a point where it became a company joke. “We’d pull out, and they’d laugh,” said Bromberg.

On June 29, Tech. Sgt. Ole E. Mancuso from Captain Richardson’s tank told Bromberg he needed a bow gunner. Bromberg refused, not wanting to leave Schwartz. Later that day, a German antitank shell smashed into the side of Bromberg’s tank. He quickly climbed out and found Schwartz wounded. Medics ran to the officer and treated him, but when they tried to take him off the battlefield he fought them. “They had to drag him away,” said Bromberg.

The next day, Richardson’s tank took a hit that killed both him and Sergeant Mancuso.

Schwartz quickly returned from the hospital and took over the company. One of his first actions was to tell his old 2nd Platoon that they were picked for every mission because Richardson hated him and hoped that he might get killed. Bromberg wrote an article about the incident and submitted it to the division magazine, but the editors declined to publish it. “They said it was too personal,” said Bromberg.

The tankers first used a bulldozer tank to break through the hedgerows. Bromberg was not impressed. When he saw his first bulldozer tank he said to the driver: “You poor bastard, you’re going to be the first person they knock off.” Bromberg was wrong. When the tank plowed through an enemy hedgerow, the Germans let it through, then hit the succeeding tanks.

The real solution came when engineers welded metal prongs to the front of their tanks like a set of tusks. A tank would ram the hedge bank, and the prongs would dig in and punch a hole through. These tanks became known as Rhino tanks and would line up three or four abreast and punch through the hedgerow at the same time. “That’s how we got through the hedgerows,” explained Bromberg.

While the Rhino tanks solved the tactical problem of the hedgerows, Allied commanders sought to solve the problem strategically. General Omar Bradley, the commander of the American First Army, planned to use heavy bombers to crack a hole in the German line between the French towns of Periers and St. Lo which tanks and infantry could pour through—Operation Cobra.

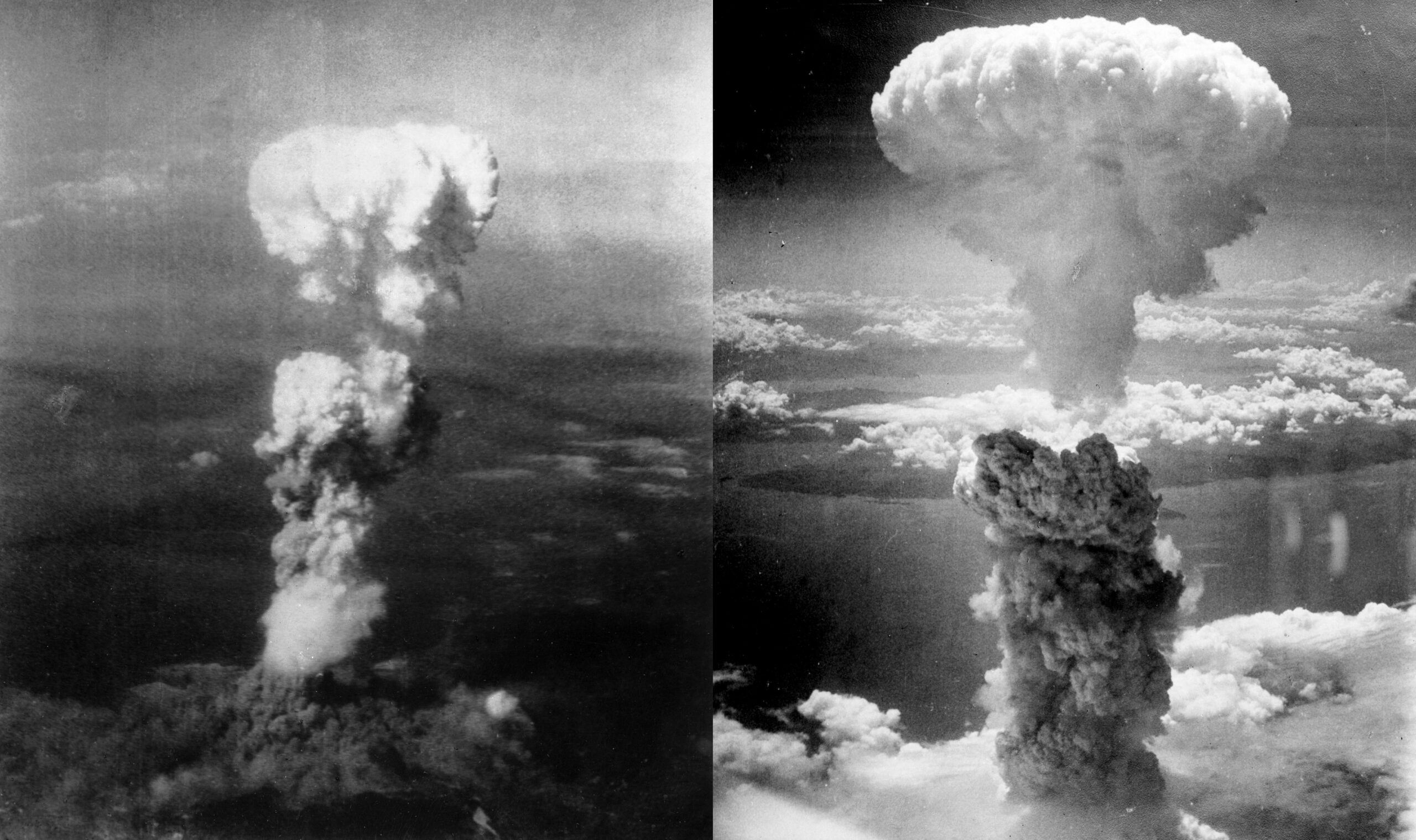

The 2nd Armored Division went into reserve near Carentan, where Bromberg and his comrades took their first showers in a month and received new uniforms. On July 25, more than a thousand Allied bombers flew over Bromberg’s position and unleashed an inferno of bombs on the Germans––and accidentally on some Americans. “There were so many planes,” recalled Bromberg. “You couldn’t see the sky.”

Soon after, the tanks rolled and Bromberg saw the effects of the bombing. “I saw dead Americans lying all over,” he said. They broke into open country, leaving the maze of hedgerows behind. Progress that had been measured in yards was now measured in miles. German resistance melted away, but the enemy made last stands in towns or at roadblocks.

To defeat the Germans in towns, tankers took to blasting church steeples, which usually housed enemy artillery spotters. “The first thing I shot at was the church steeple,” said Bromberg. It became a common practice in Europe. “You never saw a church steeple with a top on it.”

The Americans also used a new technique against the Germans. Starting in August, American fighter pilots rode in frontline tanks and radioed their fellow pilots overhead, directing them to the targets. When Bromberg’s tank clashed with a German antitank gun, a tank-bound pilot radioed a flight of P-38 Lightning fighter bombers to knock it out.

“He talked to them and they dive-bombed the antitank gun,” he said. “We’d just go on.” While the fighter planes helped, they sometimes fired short, making friendly fire incidents common. One day while Fox Company bivouacked behind the line, a British fighter plane roared in, machine guns firing. The pilot, however, failed to pull out of his dive and crashed. “He must have seen us,” said Bromberg.

On August 6, Bromberg lost another leader. Lieutenant Schwartz dismounted their tank under heavy fire when he saw a soldier go down in front of them. As he made his way to the wounded man, enemy machine gun fire struck him down.

Undeterred, Schwartz continued on until he was hit again and killed. “I became the [turret] gunner,” said Bromberg, “and the gunner became the commander.” He spent the rest of the day in the turret, aiming and firing a few shots.

For the rest of the month, the tanks of the 2nd Armored Division raced across France. They did not stop until they reached the Seine River north of Paris. Infantry often rode on Bromberg’s tank. In fact, Bromberg preferred infantry support to armor. “I felt better with infantry around me than another tank,” he said. “They carried bazookas, they could see things, and they didn’t draw fire like a tank did. The infantry was glad to see us, and we were glad to see them.”

Along the way Bromberg noticed an odd feature about each battlefield. “You’d see dead Germans but almost no dead Americans.” The Americans had been removed so follow-up troops and replacements would not see them as they moved forward. “It was bad for morale.” Bromberg also saw numerous dead cows and horses. “It was a common thing You’d see them lying on their backs with their legs up the air.”

During one break from combat, Bromberg and his crew stopped in a French house to eat. Inside, a bunch of women entered the room then burst into tears and left. Bromberg found out that the SS had shot their husbands that morning, just before the Americans had arrived.

Bromberg had a habit of volunteering for missions. When an officer named Michaels at battalion headquarters asked for volunteers to go into Vire and get prisoners, Bromberg said, “Put my name down, I’ll go.” Word spread around the company about Bromberg’s mission, and one of the tankers joked, “Bromberg, you’re not coming back. Can I have your watch?”

This scared him, but his name never came up for the mission. Months later Bromberg bumped into Michaels and asked him what happened. “I liked you a lot,” said Michaels, “so I tore your name up; I never turned it in.” That cheered Bromberg.

The running fight through France took a toll on Bromberg. One day while giving the driver a break, he drove with his head out of the hatch. His eyes started to burn, and he thought the Germans had put chemicals on the road. He visited the medics, but they said he was fine. “I don’t get no satisfaction,” said Bromberg about the incident.

On another occasion he fell asleep in the tank, but his dreams turned into a nightmare. He awoke, bolted out of the tank, and ran toward the enemy line. Tech. Sgt. George J. Delegan, the driver, also jumped out, grabbed Bromberg, and brought him back, saving his life. Bromberg also grew tired of Army rations, often throwing them away. “I was sick of it,” he said.

The division entered Belgium and Holland in September, but a lack of fuel and stiff German resistance nearly brought the drive to a halt. Near the German border at the end of the day, Bromberg stood in the turret, urinating over the side and talking with Staff Sergeant Aaron C. Evans when he saw a half-track returning from the front. All the men in the half-track wore German helmets.

Thinking they were prisoners, Bromberg pointed them out to Evans. As it drove past them, Bromberg realized they were Germans soldiers in a German half-track. “Evans, did you see what I saw?” he asked. Evans responded by dropping down into the turret, spinning it around, and firing a 75mm round into the back of the half-track. The shell tore into it and exploded, killing all the Germans.

The next morning Bromberg ventured out to the destroyed half-track to inspect the damage. Dead and broken Germans lay everywhere. Wallets and other personal items littered the ground. He inspected their belongings and realized something that had never occurred to him: they were just men, much like himself. “I never thought of those guys being human beings,” said Bromberg. “I looked at dead Germans all day long, but if I saw one [dead] American it bothered me.”

The Siegfried Line was a series of tank traps, obstacles, bunkers, and pillboxes defending the German border. “It was as bad as the hedgerows,” recalled Bromberg. To break through, engineers blew up obstacles with dynamite while 155mm artillery fired point-blank at the pillboxes.

Once through, everything changed. Men who had kept their heads out of the hatches throughout France and the Low Countries now buttoned up. “We’re back doing two miles an hour from 30 miles an hour.”

Bromberg had his most hair-raising scare at the Siegfried Line. A German dive bomber, possibly a Junkers Ju-87 Stuka, screamed down on his position one night and dropped a bomb. The plane had a siren, and the bomb fell with a whistle. Although it missed, the noise terrified Bromberg. “Between the siren and bomb I was a nervous wreck.” There was no defense against such attacks. “We were helpless,” said Bromberg. “You just had to sweat it out.”

As Bromberg and the 2nd Armored Division fought to encircle the ancient city of Aachen, the first German city to be captured by the Americans, he noticed a change in the landscape. White sheets covered most houses, while some hung swastikas.

“I used to hold my fire sometimes to save civilians,” said Bromberg, “but in Germany anything you see you shoot. Everybody you saw was your enemy.” He made one exception to the rule. One day he saw some old people crossing a field. Even thought he had orders to shoot, he held his fire.

In another instance, Bromberg’s crew spotted a German tank some distance away and fired, but the shell ricocheted off its hull. As the German tank slowly turned its turret toward their tank, the Americans, as Bromberg remembered it, “got the hell out of there.” They pulled back to an area filled with tank destroyers and told their crews about the enemy tank up ahead. The tank destroyer men agreed to engage the German tank, telling Bromberg, “Come on out and show us where it is.” His response was curt: “I said, ‘No way.’”

In November 1944, the 2nd Armored was pulled off the line for a rest. Maj. Gen. Harmon, the division commander, sent the entire division to a coal mine that had showers. When it was his turn, Bromberg stripped down to take his first shower in four months. What he saw shocked him. “I couldn’t believe my body,” he said. “I was nothing but skin and bones.”

When the Germans smashed through the American lines on December 16, 1944—the Battle of the Bulge—the 2nd Armored was too far north to play an initial role in the campaign. Assigned to Lt. Gen. William Simpson’s Ninth Army, it was transferred south on December 22 to Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ First Army to help close the bulge.

“They brought us in as a flank,” recalled Bromberg, “but my battalion was not involved.” Instead, he spent the winter months just trying to stay warm, standing behind the tank’s exhaust or sitting close to the transmission between the driver and the bow gunner.

The Americans sealed off the bulge in late January 1945, but there was more fighting ahead. As the 2nd Armored renewed its drive into Germany, Bromberg began to withdraw from his fellow tankers. “I made it my business not to get close to anybody,” he said. He especially avoided replacement soldiers, who tended to get killed quickly. There were times Bromberg did not know the driver next to him. One replacement did impress him, though, a man named Shaffer. “He was calm,” said Bromberg. If the tank took a hit, “he’d climb out and light a cigarette. He really had nerves of iron.”

Bromberg let his guard down with replacements once. When he could not find anyone to sit next to after getting chow, he plopped down next to a replacement from Pennsylvania. They struck up a conversation and became friends. His new friend kept asking, “When are we going to go in and get some Jerries?” Bromberg kept reassuring him the time would come.

Finally, the unit moved out. The replacement fought in a different tank, so when the unit finally pulled back after a few days of fighting, Bromberg went to his gung-ho friend’s tank to ask him how he liked it. He asked the crew where the replacement was, and one of the soldiers said, “On the first day he went berserk, and we had to pull him out.”

Besides his attitude toward replacements, Bromberg changed some of his usual battlefield practices. Usually, after a three- or five-day fight, the unit would pull back, and Bromberg would run to the company headquarters to see who had returned. “I stopped doing that.” He also stopped smiling. “It got to me,” he recalled. “I wasn’t so cheerful.” One day after some particularly hard fighting when the entire company was shot up, he turned to his driver and said, “We were knocking on the door.”

The intense fighting also took a toll on Bromberg’s fellow soldiers. “A lot of men shot themselves,” said Bromberg about self-inflicted wounds. Army discipline was harsh to anyone suspected of deliberately shooting themselves to get out of combat. If anyone claimed they had shot themselves while cleaning their weapon, an officer would pass around an affidavit attesting to the accident for the men to sign. “I never saw anyone do it, but I signed it,” said Bromberg.

He also pointed out that medics would sometimes take mercy on the victims. “Combat medics told me if they ever saw powder burns on a man’s uniform from shooting himself, they would cut off the parts with burn marks before sending him to an aid station.”

The Rhine River stood as the last natural boundary into Germany. The Ninth Army crossed on March 23, 1945, but by the time Bromberg’s tank reached the river there was already a pontoon bridge in place. He did not explicitly remember crossing the Rhine. He and his crewmen had crossed so many rivers that the Rhine was just another one. Bromberg did not like crossing rivers. “Every time I was driving and we came to a river, I’d switch,” he recalled. “That’s why they didn’t make me a tank driver.”

In early April, the unit received heavy M26 Pershing tanks. Bromberg was not impressed with the new weapon. “It was all computerized,” he said. “No way could I have functioned in that tank.” He preferred the simplicity of the Sherman. In fact, he fought the whole war in a Sherman with the 75mm cannon and never upgraded to the thicker armored M4A3E8 Sherman, the “Easy Eight,” which carried a much more powerful 76mm cannon.

One day in April, Bromberg’s tank took a hit, and he jumped out. While running back to the American lines, he came upon a German in a foxhole gripping an MP40 machine gun, which the Americans called a grease gun. “I stood there paralyzed,” he recalled. But the German held still too, so Bromberg took off running again.

As he reached a group of infantrymen, he turned around to discover the German running right behind him with his hands behind his neck. A scared and angry Bromberg grabbed one of the infantrymen’s rifles to shoot the German, but the men restrained him, saying, “Don’t do that!” They told Bromberg that they recognized the German by his helmet and were going to shoot him but he was running too close to Bromberg.

A combat medic showed up and took Bromberg to a first aid station. “I was a physical wreck,” he admitted. Suffering from combat shock, everything became a blur. All he could remember about the station was picking up a cigarette butt off the floor. “The next thing I knew I was in a field hospital,” he said.

German border. The last line of defense included tank traps, pillboxes, and bunkers. Fighting became more intense east of the border.

Doctors checked on him daily and asked him how he was, but Bromberg, still suffering from his trauma, could not speak. The soldier in the cot next to him had been wounded and spoke easily with the doctors and nurses. Bromberg thought to himself, “I wish I could do that.” The doctors sent Bromberg back to another hospital and sent the wounded man to the front.

When Bromberg disrobed at the new hospital he was shocked. He was even skinnier than he had been in Holland back in November. Doctors gave him shots to increase his appetite and fed him heartily. He eventually began to put on weight. Once well enough, he was transferred to a hospital in England.

Bromberg reached England on May 9, 1945. A doctor called him into his office and told him that because he had fought in North Africa, Sicily, and Europe he would give him a choice: He could either stay in England or go home. Concerned about war rationing, a lack of alcohol, and nothing to do back home, Bromberg told him, “I’d just as soon stay in England.” The officer agreed to his request.

Later, a soldier who knew Bromberg’s family visited him and told him none of those things were true about the United States, that his superiors only told the men those things to prevent them from feeling homesick. Bromberg immediately changed his mind and went back to the doctor to plead his case. The doctor tore up his stay order and signed a new order, allowing Bromberg to board a troop ship bound for home.

A war-weary Bromberg returned to Columbus, Ohio, weighing only 116 pounds, having lost 44 pounds while overseas (not counting the weight he had put back on in the hospital). As soon as he was discharged he took off his uniform and never again put it on.

He had a hard time adjusting to civilian life, drinking too much and picking fights with anyone who looked at him the wrong way. He suffered nightmares of German dive bombers roaring down on him. He refused to see war movies. Even driving was difficult. Every time he braked for a red light, he would double clutch, infuriating his father, who would yell, “What are you doing?” For an entire year he would pinch himself when he woke up to make sure he was sleeping in a real bed.

Eventually, Bromberg’s nightmares faded, he cut down on the drinking, and relearned how to drive a vehicle that lacked a cannon and tracks. His girlfriend, Betty Farrell, eventually dragged him to see the movie Mister Roberts, breaking his ban on war movies. Bromberg married Betty in 1955, and they had two boys: Scott in 1957 and Craig in 1960. For work, he opened up a plumbing business and, as of 2015, was still at it. Looking back on the war, he reflected, “I was scared all the time but got used to it.” The war made him the man he is today. “Nothing bothers me,” he declared. “I sleep good, and nothing gets me excited.”

He only regrets that he never spoke to his family about his war experiences. “After I got home I never talked to my father about the war,” he said. “I never told my brother. I wish I would have told them about it.”

When asked if he would change anything about his war experience, he said, “If I had to do it all over again––I would have kept whiskey in my canteen.”

great reading

very moving

What a great man I would not like his experiences but I would like to be part of that generation.

Huh?…but the American cannon had an advantage: an automatic breech-loader. The spent shell quickly popped out of the breech and the loader shoved in another round. Thx!!

Picture…Private Bromberg drives a weapons carrier pulling an artillery piece at Fort Knox. Looks like an M6 Gun Motor Carriage. Mounting a 37 mm AT gun.

Exactly right, it is a weapons carrier.

A very moving story of an ordinary man who experienced extraordinary events. As an Englishman I owe him and his comrades a great deal.

Compelling story, thank you Mr Bromberg for your outstanding service to your Country. As Patton said “war is hell” and this reads like a journey to hell and back.

N.B..the allies referred to the MP40 as the

‘burp’ gun. The ‘grease’ gun was the American M3 SMG.

Great story. Thank you for your service PFC Bromberg!

Insightful read.