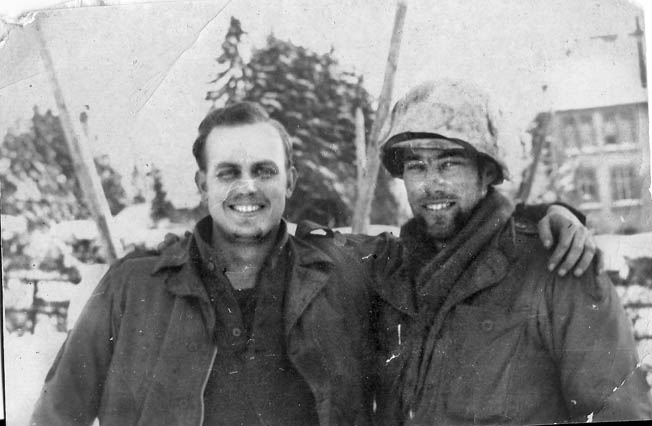

By Ralph and Mark Puhalovich

Ralph Puhalovich was born on April 17, 1925, in Oakland, California, to Flora and Ivan Puhalovich. He was the youngest of three children; his brother John was 10 years older and his sister Marie was four years older. After graduating from Oakland High School on June 19, 1943, he reported to his draft board on July 5 in San Leandro, California, then boarded a bus headed for the Presidio in San Francisco, California, and began basic training.

After three weeks, he was sent to Camp Adair in Corvallis, Oregon, where he was assigned to a heavy weapons company in the 275th Regiment, 70th Infantry Division—an assignment that was to be short-lived. This is his story.

At Camp Adair, in the summer of 1943, we went through drills and marches. I was carrying part of a heavy machine gun. The lightest piece weighed 31 pounds and the other piece weighed about 37 pounds. Nobody could carry both pieces, so you’d either have one or the other. We went on hikes and, I have to say, I never fell out and I finished all of our maneuvers.

One of the things we learned was that the motto of the infantry is, “Ours is not to question why, but to do or die.” We were to follow our orders whether or not we understood the reasons.

I was fortunate enough to get a leave for Christmas. I got on a train and went home. I surprised my family because I didn’t have time to call. It was a nice treat to see the family and my girlfriend (and future wife), Louise Campanella, before the long journey to join the fighting.

Ralph Puhalovich’s stint in the 70th Division came to an abrupt end; in early January 1944 he, along with others, received orders transferring them to the 1st Infantry Division, which was at that time training in England for the upcoming Operation Overlord—the Allied invasion of Normandy. He said his goodbyes, got on a train, and made the long trip eastward to New York.

We spent four days in New York before boarding a “Liberty” ship and heading across the rough North Atlantic on our way to Belfast, Northern Ireland. After spending some time at an Army base there, we headed to Glasgow, Scotland. From there, a train took us to southern England and we ended up in a little town called Swanage. I was assigned to the Anti-Tank Company of the 26th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division.

England, May 1944 to June 1944

If you look at a map of England, at the very bottom along the English Channel you’ll find Swanage. We could see France from there and the Germans were throwing big artillery shells across the Channel at the town next to us. They obliterated the town completely. Then, every night at 10:04, we’d hear a German plane come overhead. It was a twin-engine bomber. The engines were out of sync, which created a screeching noise; it was all psychological. They’d come over at exactly 10:04 every single night to drop one bomb someplace. We never knew where this nightly bomb was going to land.

We nicknamed the plane “Bed Check Charlie.” The Germans were trying to find out where all the British antiaircraft guns were. The English were smart enough not to shoot at them.

That’s what the Germans did; they were very consistent. You’d be so used to them not attacking, that’s how they crash through when they finally deviate from their routine. The 1st Infantry Division had already fought in Africa and Sicily so they knew to always remain vigilant. I was very fortunate to have veterans explain these types of things to me.

We were assault troops. They gave us gas masks, which we tried on and were to run in, but you could hardly walk in them. They decided the masks were too big, and we were given another type of mask. They had us enter a room where they would pump tear gas in. We’d have to walk in and take off our gas masks. It was enough to make you choke and cough a lot but not die. Then we had to hike five miles with these things on. Going five miles is tough, let alone with gas masks on.

We were then given “gas-impregnated clothing.” It wasn’t impregnated with gas; it was impregnated to prevent gas penetration, because everybody assumed the Germans would use poison gas like they did in World War I. We dressed in the clothing and then had drills in case of a gas attack. We had to get under a transparent cover to shield us and all our weapons. We’d stay there until someone blew the whistle to end the test.

We were also given a life vest made out of rubber that flapped over your waist. If you went into the water, you’d press a button and you’d have the vest inflate around you. It had a whistle and light in case it was night. You could blow the whistle and you could see the little red light. Thankfully, we didn’t have to use them. Even though I couldn’t swim, I didn’t like the idea.

At one point, a few of the others in my unit and I were selected to go to Dover, in southeast England, on temporary duty. The Army had come up with a great plan to fool the Germans into thinking the invasion would come across the Strait of Dover to the Pas de Calais, rather than at Normandy. To keep the enemy fooled, the Army built a fake camp there and let the news leak out that Patton was there and that he would be leading that fictitious army.

They told us that we were to be on guard duty around this camp, which was full of empty tents, with orders to shoot. There were also fake airplanes there and inflatable rubber tanks that looked pretty realistic from a distance.

One day I was standing guard by one of these tanks and the generator that pumped the air in suddenly quit and the tank began to shrink. The barrel started to sag. Somebody came along and got the generator working again and the tank got reinflated to its proper size.

After three days in Dover, we were returned to duty. We had some down time in Swanage and were able to enjoy the town, go to the pubs, dance, and talk to the locals. I met a girl named Marge after some of us went to a dance. The girls would stand outside the theater, hoping a GI will go in and they can accompany him. They were looking for company, which is fine.

Marge was very attractive and we were hanging out in a pub after the dance. I said, “All your men are gone,” and she said, “Yes, and there are a lot of Americans and I’m engaged to three.”

I said, “Excuse, me?”

“I’m engaged to three.”

“I don’t understand.”

“They want someone they can talk to and write to, so I agree; I have three rings.”

I said, “Well, what happens when they all come home?”

She said, “I’ll cross that bridge when I get to it!”

My unit moved out the next day.

D-Day, Omaha Beach, Normandy, June 6, 1944

We were given our orders to go to Plymouth Hoe on the southern coast of England. Plymouth Hoe is where the first migrants to America came from. We trained there, waiting for orders to move out. We were to load all our equipment on an LCT (Landing Craft Tank).

An LCT is like a big barge. At the back of the craft is where the captain and all the equipment is. In the front, there’s a big ramp that goes down, allowing you to load (and off-load) the heavy equipment. In our case, as the antitank company, we had three antitank guns that were pulled by half-tracks. They loaded them in a predetermined order for easy exit upon landing.

We stayed there a total of seven days because it took a long time to load the heavy equipment. After all the equipment was loaded, the infantry came in on the last day and boarded the LCT. Ours, which was actually a Canadian LCT, was manned by an English crew.

The Canadians brought us a box every day with Heinz Celery Soup for our rations. You pop off the top and right in the middle of the can there’s an element that heats the soup. One guy said, “Well, you know what, I wouldn’t be surprised if one of these was a damn bomb!” It wasn’t, but we always said that.

We were there until June 5, when we left port and headed for someplace else; we weren’t sure where, but we thought it was Normandy. The storm got so bad that we received orders to turn around and go back to Plymouth Hoe.

The next morning, we were right where we were the day before. History states that Eisenhower said, “There’s supposed to be a big storm coming and tomorrow’s an iffy day; June 6th is the day we’re going.” It took a lot of courage for him to say that because the next opportunity could have been a long wait. As a result, June 6th became known as D-Day.

The water was very choppy and the seas were rough. Many of us were having a hard time not getting sick. We were still quite a few miles out when all the ships started firing their guns. We couldn’t see what they were aiming for or what we were heading into, but the sound was deafening. There was a great deal of spacing between all the ships and crafts heading for the beach so we had no idea of the scope of the attack. It was a foggy, misty day which reduced the visibility even more.

So I was headed for my first action and feeling sick from the seas. I couldn’t see what we were facing, but the continuous firing of the battleships told me it was big. I was looking over the side trying to keep focused on something on the horizon.

Unfortunately, I caused a bit of a panic among the Navy. While I was looking over the side of our craft, my helmet fell off into the water and began floating back toward the Augusta, General Omar Bradley’s flagship. My helmet is bounding back in the water and there’s a lookout on the prow of the cruiser and he sees the helmet and yells, ‘Mine!’

So they take evasive action and, as far back as I can see, ships are taking evasive action. I have no helmet so I was told to take one off a casualty on the beach. (When I got to the beach, there was a guy in a foxhole, all ashen color, and I thought about taking his helmet, but it had a big Ranger insignia on it and I thought, “I don’t want a target on my head.” I did find a helmet later on.)

Eventually we could see the beach. I couldn’t believe what I saw. It was a traffic jam of crafts, and bodies were floating in the water. The beach was full of soldiers and many were not moving. As we’re looking onto the beach, the veterans are saying, “Same old, same old.” I asked what they meant. “Slapton Sands” they answered. It looked identical to Slapton Sands—a place in England where some of the troops had trained in preparation for Omaha Beach.

All divisions had three regiments; the 1st Division’s were the 16th, 18th, and 26th Infantry Regiments; I was in the 26th. The first wave for D-Day is the 16th Infantry Regiment; they went in at five in the morning. Going next is the 18th Regiment in the second wave, and we, the 26th, are in the third wave. (For each amphibious assault landing, the order is changed so that the leading regiment isn’t always the same. The leading regiment can take a lot of casualties.)

As we got closer to the beach, we hear something loud close by and someone asked, “What’s that?” and someone else says, “Rifles and machine guns.” Next thing we know bullets are hitting the sides and we have to take cover; now we know this is the real thing.

Our LCT had an English crew and some of them were known as Cockneys. A Cockney is to England what someone from Brooklyn is to the United States. They’re different people, a little rougher. They talk Cockney (slang); the English can hardly understand them. They don’t pronounce words very well.

One of the Cockney crew members was using a 15-foot-long pole to measure the depth of the water, before anyone gets off the craft. He said he will let us know when the water is less than four feet deep. He gave us the okay; our first two guys drove off in a jeep and went straight down. One guy popped up; he was coughing and trying to catch his breath. When he finally does, he heads for shore.

The second guy didn’t come up for quite a while. Finally, he came up and was pulled back to safety. The jeep and the trailer with the captain’s radio and the platoon’s equipment went to the bottom. Some men went looking for the little Cockney; they were going to kill him because of what he did. He took off running and stayed hidden until we got off the boat.

We were supposed to land in the third wave but there were a lot of problems getting everyone to the beach. We waited until the afternoon and attempted to land. When it was our turn, we put the ramp down. My friend Mooch—Mutchinsky, who was the half-track driver—and I were to get the half-track off the boat. I was directing him when a guy ran up and said, “Hold it! Hold it! This beach hasn’t been cleared of mines.”

As a result, we had to land someplace else. We picked up and went farther down the beach. But there was still no place to offload—it was very crowded, so we went back out to sea for the rest of the day and night.

We offloaded on Omaha Beach on June 7. We were given the objective to go up to the bluffs at the top of the plateau to set up our guns. We went up about half a mile to this point and there’s nothing there but a “T” intersection.

We started to take cannon fire and I asked Sergeant Peters, “What’s the noise I’m hearing that’s behind us?” He said, “That’s American tanks.”

They have a short-barrel gun, they don’t have much range, and they’re firing at us! We got on the radio and they ceased fire and told us to go back to our original position. So we went back down to the beach and dug in.

The Germans were shooting at us from the cliff and were not visible to us. They were in a high, thick concrete structure. On the top of the structure, they had a few very ingenious contraptions. We couldn’t see anybody but they were in these big turrets. I guess they would press a button and this round turret would come up and a German gunner would fire his machine gun. As soon as he had to reload, he’d lower the turret. We were shooting at them with no results. They had armor around them and concrete in front of them so we were not making any progress in taking these guns out.

We had one thing that they couldn’t do much about––the sky was full of American planes, big bombers. We knew they were American planes because they had three white stripes and a star on the wings and fuselage. They dropped huge bombs on the concrete structures, taking many of them out. They had to eliminate these two eight-inch German artillery pieces, protected by thick concrete and located on the top of the plateau. The opening was just big enough for the barrel to stick out. That was one of the main objectives; we had our big ships exposed in the open water and had to take out these guns. The Germans could have done immense damage to our progress on D-Day if they took out our ships.

In addition to bombers, gliders were used to sneak troops farther behind German fortifications. The glider pilots were told to land near the Merderet River. Unfortunately, the guys piloting the gliders had little control; many of them landed in the river. Later, we were up on the plateau and there were gliders sitting there with 10 soldiers in one of them; all were sitting in their seats, dead. The glider idea was a good one, but we lost a lot of men and it didn’t work too well.

Once we had secured the plateau, we settled in for the evening. A nervous GI came over to join us and we asked him, “What’s the matter?” He said, “Well, I was sleeping and hit something and they were hobnail boots [German boots]. I was in a trench with a dead German! I didn’t want to be there.”

The next morning we got up (we slept under our half-track for protection), and there was the dead German soldier. Usually they weren’t as tall as I am, six foot two. This guy was six five and was lying on his back. He’d been firing a gun and his arms were sticking up, stiff with rigor mortis. Somebody went into his wallet, found a picture of him on his wedding day in a striped suit, and put it in his extended arm. Here’s this dead guy looking at his wife and him on their wedding day. I mean, that got me right in the heart.

A veteran we were with named “Punchy”—an ex-boxer who had been with the 1st Division in Africa and Sicily—pointed at the dead German and said, “Okay guys, here is your enemy. Not much is he?” We said, “Yeah.” We’re brand new, what do we know?

Punchy said, “Well, if I sit down there I’ll get wet. If I take off my helmet to sit on, that’s not too bright. So, Jerry, I hope you don’t mind.” So he sat on the dead German’s chest and ate his breakfast. What he was doing was showing us: “Don’t worry about the dead Germans; worry about the live ones. Just forget him.” It was a very graphic lesson and one I didn’t forget.

We were there for a day or two and then moved out and went across Normandy.

One day we were assembling all the equipment and were using the open field of a farm to get organized when we noticed a woman and a little girl holding hands. The mother was holding a stool and they were trying to chase down a single cow in order to milk her. The little girl stood there staring at her mother and then staring at us.

I’m sure she didn’t know what all these armed men were doing walking down the road in front of her home. I had a candy bar in my pocket and broke it in half. I walked over to the little girl and gave her the candy bar. She smiled at me, curtsied, and said “Merci beaucoup.” Her mother also said thank you. She looked terrified at seeing a whole regiment of soldiers plus tanks and half-tracks on her property.

Anyway, we started to pack our things and get ready to head out when I felt a tug at my pant leg. I looked down and saw the little girl. She picked a flower and gave it to me and curtsied. It brought tears to my eyes. I think of that to this day and wonder what became of the little girl.

As we were moving to our next position, I engaged in a conversation with a couple of GIs that were scouts. When going down a road, the infantry usually has two or three scouts in front, spaced 15 yards apart. The enemy sees them coming and, if they’re smart, they duck down, let the scouts go past them, and open fire on the main unit.

These two guys had been in Africa, Normandy, and Sicily. I asked them if they thought their job was too dangerous. They said, “Yeah, no.” Confused, I said, “What do you mean?” One said, “They don’t shoot the first scout and they usually don’t shoot the second scout, but they’ll shoot you in the back if they have a chance. They want the main body. If they start firing, we take off, fight our way back, and we always make it back.” They were really experienced, but you can only push that so far. I learned a lot from the veterans. I was very fortunate to have veterans willing to teach me.

My division originally went to North Africa with Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. as the assistant division commander. On June 6th he had landed with the 4th Infantry Division on Utah Beach. I was fortunate to meet him. He came over to talk to me and said not to salute because the Germans are still there and may be watching. He asked if I knew

who he was, and I said, “Yes, General Roosevelt.”

He said, “No, they took my rank away and now I’m a colonel. You know this was my division, and this is the best division in this army. You’re lucky. See you around.” That was a high point in my service when he came to talk to me. As a rule, a private doesn’t get to talk to generals. (Unfortunately, he died a few weeks later of a heart attack.)

The Road to Caumont

I was wounded three times. The first was on June 9, 1944. Our 26th Regimental Combat Team was on the road, headed to a town called Caumont. We came under intense fire, both from the Germans and our own troops. Our own tanks were firing at us because someone fouled up. We were not supposed to be out there, way out in front of everyone else and making a lot of dust.

We were bringing the rations and mail up to the front of the convoy, but we were spotted by the German artillery. They started shelling us. My buddies jumped into foxholes but I couldn’t. The shells picked me up and turned me around more than once. Every time I tried to move after hitting the ground, another shell would hit and lift me off the ground again.

The ration box and water can I was carrying were completely riddled with holes and I took a tremendous head pounding. My nose and ears were bleeding, but I did not go to the aid station immediately—I was a young kid and wanted to show the veterans I was as tough as they were.

We eventually made it into Caumont. On the road in, there was a French policeman with a whistle and baton controlling traffic. I turned to Peters and said, “Boy, are all the French like this?” He said, “Son” (they always called me “Son”), you never know what the French are going to do.”

Then we moved into position behind another company. As we were relaxing, we heard a few shots around us. I said, “That’s not one of ours.” He said, “No, that’s a German Mauser. We have a .30-caliber bullet. Theirs is a little larger and it’s bolt action and it makes a lot of noise. It’s back behind us somewhere, but don’t worry about it.”

Pretty soon we heard another shot and then no more until the next day. Later we heard that a GI had been shot, and someone had killed the French policeman. Come to find out he was a German soldier who was dressed like a French policeman and was spending part of his day being a sniper.

I lost one of my friends, Robert Short, in Caumont. We had a cease fire for three hours, then it was extended for another hour. There was a German soldier who was looking at our gun position on the road where he wasn’t supposed to be. He was looking right down our gun barrel. As soon as the cease fire was over, we were hit with an incoming mortar shell. It hit a building, and the shrapnel, concrete, and glass came down. I didn’t get a scratch. Somebody was looking after me, obviously.

I called out for Short but didn’t get an answer. I went looking for him and found him lying on the floor. The sergeant said he’d call the medic. I said, “Sergeant, he needs a stretcher; a medic can’t do anything for him. He needs to go to the doctor.”

So he called, and I stayed with Short; I thought he was dead. We took him to the doctor who came in, looked Short over, looked at me, and covered Short with a sheet and said, “I’m sorry, he’s gone.”

I’m up here, watching this like an out-of-body experience. I put my hand on his chest and said, “Short, some day, I’ll come back.” Then I covered my face and tears came down. I went where the other gun position was and asked if I could use the phone. I called up my squad and said, “Short is gone and I can’t come back now.” They said, “We understand, take your time. We’re okay.”

I was there for a while but returned to my squad and to my position. I found Short’s blankets and personal stuff next to mine. I said, “I can’t go in there.” I just could not—it hit me hard. I cried a lot. I have never forgotten Short, and I never will, because you’re together at all times. It’s purposeful—he watches your back, and you watch his. Fifty years later I did go back and visit his grave. That brought back lots of painful memories, but I was glad that I did.

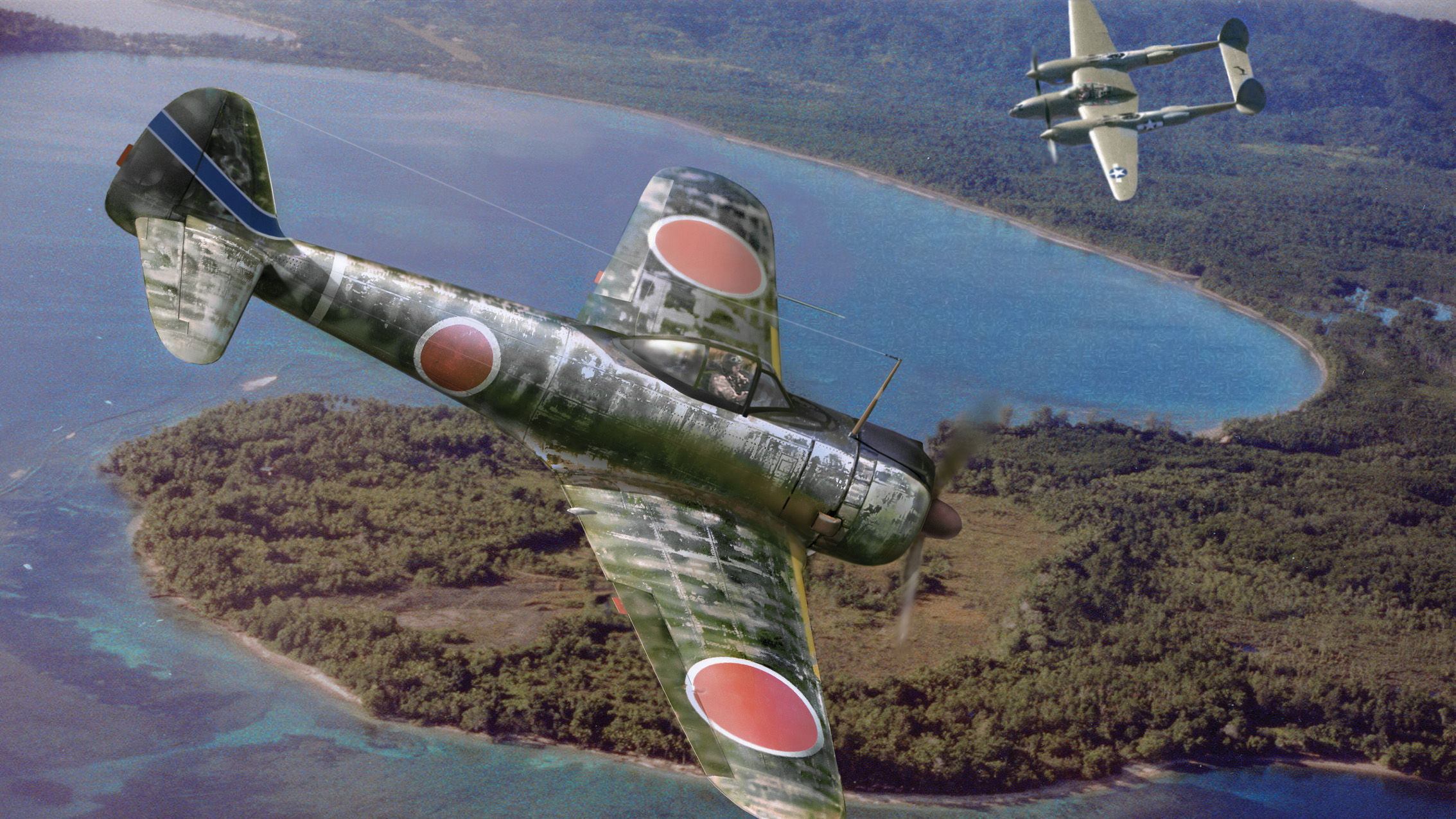

The second time I was injured, we were in Caumont. It was around July 25, and we would be leaving soon for Saint-Lô. Mooch and I were in a half-track with a .50-caliber machine gun. We were pulled in behind a house so the vehicle couldn’t be seen from the road. A German fighter plane came over, a Focke-Wulf. He headed for us, strafing. The half-track was loaded with fuel, ammunition, hand grenades, machine guns, and mines—it’s a floating arsenal.

The plane came down, hit the half-track, and there was one massive explosion. We were off to one side, thank goodness. A big flame goes up, and then all the .50-caliber machine gun ammo and the hand grenades blow up. What was left was a pile of junk. Mooch and I went to get another vehicle.

After we got the new half-track, we were following some other vehicles; I was standing up at the gun. We came up to some tall hedgerows that limited our visibility. The three vehicles ahead of us took off and went around a corner. We came around the corner, and when we turned, the vehicles were stopped right in front of us.

Mooch yelled, “Hang on!” as he pulled the wheel over so we wouldn’t hit them. We turned sharply and went through a big hedgerow. Unfortunately, behind it was a big oak tree. We hit it while I was holding a machine gun; the gun broke my wrist.

The medic couldn’t treat me for a broken wrist; I had to go to a tent hospital on Omaha Beach. The doctor said, “You got a lucky break.” I said, “How do you figure that?” He said, “Your wrist is broken and we have to send you back to England. We have no way to take care of you here.”

Headed for England

They flew me over to Wales in a big C-54. I felt bad because I hadn’t been wounded; I was injured but not wounded. I was put in a hospital, filthy dirty—me, not the hospital. I had had the same clothes on for two or three weeks; there was nothing to change into.

They put my arm in a cast and drew what had happened to me right on the cast so the next nurse or next doctor could see that I had a broken right distal radius. It was fractured; the hand had to stay immobile.

I was sent on to England to a hospital just outside of Bedford with others who had been wounded. One particular soldier sitting across from me was crying. He had a cast and his thumb was sticking out. I asked him, “Can I help you?”

He said, “Well, I live in Nebraska and I’m a farmer. I was assigned to an outfit, I don’t know what outfit it was; I was a replacement. I was in a firefight with the Germans and when I reached for my ammo clip, I couldn’t pick it up. I couldn’t understand it.” The German bullets had cut off all his fingers. All he had left was a thumb.

He said, “I’m a farmer and what can I do? I’m right handed. I don’t have a hand.”

What do you say to someone like this? His life is completely different. We kept in touch. I wrote to him a few times, but I thought of him many times. Later, I heard that he died at a very young age. That’s what happens. Veterans don’t last. I’m an oddity, and I’m still here. Maybe I could duck faster than the next guy, I don’t know.

Once my wrist had healed, I found that I had lost a lot of muscle and had to do extensive rehab. I saw a lot of soldiers with injuries a lot worse than mine and I couldn’t help but think how this was going to change their lives forever. I also couldn’t believe the care that all the wounded got from the nurses and doctors. I had never been in a hospital before so I had never seen people caring so deeply for complete strangers.

I was sent from that hospital to Southampton, on the English Channel. I was there for a week or two before I got orders that I was going to rejoin my division.

My regiment had broken through Saint-Lô and had made it all the way to the Siegfried Line while I was recovering. U.S. troops had surrounded Aachen, but hadn’t intended to invade the city. Aachen was a historical and important city to the Germans, so they put up fierce resistance and the plans changed regarding Aachen.

There was intense bombing that leveled much of it, and then assault troops went door to door securing the city. By the time our regiment entered the city, most of the heavy fighting was done. I ended up doing guard duty for the prisoners.

We stayed in Aachen for a while and left in early November to enter an area called the Hürtgen Forest.

The Hürtgen Forest

The Battle of the Hürtgen Forest was a series of battles starting in September and lasting until December 16, 1944. It was the biggest, and one of the longest, battles in U.S. Army history. There were massive casualties on both sides.

We would be shelled, fired upon by tanks, and encounter infantry troops. It was a constant fight which turned out to have more danger than we could have imagined. The shelling and tank fire into the trees resulted in wood shrapnel that could do more damage than the bullets. On November 18, I was injured for the third time.

I was sent out to hunt tanks with a bazooka. I was lying under a tree and heard this little voice tell me, “You better get out of here.” In combat you learn to listen to the “little voices.” I got up and went over to another GI who was dug in about 15 yards away. At that moment, a mortar round came in and hit the exact place where I had just been.

Then another round came in and exploded in the trees above us; I got hit in the buttocks with shrapnel. Later, at the aid station, there was a captured German there who laughed when he saw my wound; one of the other guys in the aid station smashed the German in the head with the butt of a rifle for laughing.

Once again I was pulled from the fighting, but I spent only a few weeks recovering. When I was ready to go back, I was sent to a replacement camp. On Thanksgiving Day I was put on a truck and taken someplace; I had no idea where I was. While I waiting, one of the officers said, “Okay, all the men from 1st Division report to the mess hall. You’re going to have an early dinner so you can go.” So we left the mess hall after dinner, but we didn’t rejoin our outfit right away.

Fortunately, our division finally got a rest on December 6, after six months of continuous fighting. I came back to the outfit in December 1944 and joined them in Butgenbach, Belgium—a city our outfit liberated. When I got to Butgenbach, it was Christmas Eve. I was just in time for the Battle of the Bulge.

Battle of the Bulge

We went down into the town. We were not allowed to go anywhere without our weapon. You didn’t put it anywhere else. There was a Catholic church and they were having Mass. Being Catholic and a former altar boy, I went in with my helmet on and my gun. It seemed terrible to be in a church with a rifle and a bayonet and other stuff.

I took my helmet off and set it down, then went in a pew with my loaded rifle with the safety on and stayed for Mass. Some guys went to Communion and some didn’t. I didn’t go because Catholics have to go to Confession every once in a while, and I hadn’t done that.

They sang the same songs that we did at Christmas, except in a different language. We knew the tunes but we didn’t sing. We went outside and found one of our guys who hadn’t gone inside. He was much colder than we were and, while he was walking with us, he tripped, fell down, and hit his head on the concrete, knocking himself out. That’s how bad of shape we were in. Practically all of us were frozen.

Some of the guys started talking about Corporal Henry Warner who was killed in action before I got back to the outfit. My friend, Bob Rigg, told me that he witnessed Warner knock out a number of tanks with a 57mm antitank gun. One tank was coming back after Warner killed the German commander; he knew they were coming so he started running. He wasn’t running away, but he was scared. All he had was a pistol.

Rigg said that he, Rigg, was in a hole with two of his buddies that had been shot in the lungs and he couldn’t get out because there were tanks surrounding them. Rigg said, “I’m in the hole and I knew I had to get some help for those guys and I’m waiting there and here comes Warner running over. I could hear the tanks and could see something going on. Warner came and saw me in the dugout. He jumped in the hole with the pistol and when the tank came up he was firing at the tank with his pistol.

“Warner was aiming his pistol down the 23-foot-long barrel of the tank’s gun to blow it up. Chances are like 9,000-to-one that that’s going to happen. But he was doing that on purpose. So Warner was blocking the hole and he was killed, machine gunned. He blocked up the hole to save my buddies and he gave up his life so they could live.”

When the war was over, Congress awarded Warner the Medal of Honor. That’s the highest honor anybody can have. He was a hero, no question. After the war there was a German Army kaserne in Bamberg that the Americans appropriated. They renamed it “Warner Barracks.”

Warner was from North Carolina and was only 21 when he died. He was a real quiet, unassuming, soft-spoken guy, He didn’t drink and he didn’t swear. You wouldn’t suspect that he would be a hero. I read in a book that he had also done more heroics the day before and had taken out a tank or two.

Bronze Star, Belgium

In Belgium we were so cold we practically froze to death just being outside; it was reported to be -20C, but who knew for sure? In the history books I’ve read, they say that the cold killed more troops than the fighting did, on both sides. The weather was so bad that everything stopped moving except the shelling.

We were in our holes and dugouts from Christmas Day to some time in January. A few of us had a little food, but that was all we had. I went into the Bulge weighing 185 pounds and the next time I was weighed, I was 155 pounds. All the supply lines were down, and the weather was so bad it was like the world had stopped. They couldn’t get anything to us. We were starving. The snow in places was over six feet deep.

Once the visibility improved, our planes started flying and dropping supplies to us and bombs on the Germans. We started moving again. We were given orders to move on to Büllingen, which is closer to Germany.

We were on our way to Büllingen on January 25, 1945. I was in the lead as our scout. The snow was high and, as I was the tallest of the men, I was volunteered to lead the way. The youngest always seemed to have to take the lead. I wasn’t doing too well; I had dysentery and had to stop often to take care of things. I felt miserable but in the end my illness ended up saving some lives, maybe even my own.

On one of my stops, as I was squatting down, I heard some voices. I snuck up behind what I could now see was a German machine-gun emplacement. I snuck up as close as I could and let go with some shots and yelled for them to surrender. Fortunately, they all raised their hands and we ended up taking them prisoner.

We knew that the Germans always had at least a pair of machine-gun emplacements so we carefully sought out the second one and disabled that weapon as well. I was rewarded with the Bronze Star for that on July 24, 1945.

Again we returned to attack the Siegfried Line and continued to the Roer River in February. We eventually came to the Rhine, where we crossed the Remagen Bridge in mid-March. This was a crucial piece in our further occupying Germany. The bridge collapsed 10 days after the U.S. Army had captured it.

Schonbach, Czechoslovakia

The division took part in the encirclement of the Ruhr Pocket and went on to capture Paderborn. In April 1945 we entered Czechoslovakia. It was our last position during the war before we got word the Germans had surrendered.

When we were told that the war was over, one of the men in our platoon mentioned that the same thing happened to his father in World War I, and many Americans were killed because not everyone put down their weapons. He said he wasn’t putting down his weapon, so none of us put down our weapons. Despite being told it was really over, we ate our celebratory meal with spacing between us and vigilantly looked around.

We were camped near a farm where we could see some movement and went over to check it out; it was a mother and her daughter. We started conversing, but my German was pretty limited. Over the next few days she taught me a lot of German and I was catching on. Our lieutenant saw the farmhouse and told us to throw the people out because we were going to be sleeping in beds tonight.

When we went over there to break the news, the mother wanted to know where they were supposed to live; we told them we didn’t know. They ended up staying close and I continued learning German.

A squad of us was sent to an area that sounded like “Long Vasser,” which was a position for German aircraft and munitions. There was a great big enclosure of barbed wire fence and inside were little huts. This was near the city of Schonbach, which means “pretty creek.”

We had 75 German prisoners there and our job was to guard them. We sorted them by city so they could be returned to their hometowns. While we were waiting for trucks and drivers to show up to transport them back to their families, we were pretty relaxed.

Schonbach is a musical city famous for handcrafted musical instruments made from wood—violins, guitars, clarinets, mandolins, and more. It so happened that a fellow in my platoon, who was a medic, picked up a mandolin; he had a mandolin at home that had been made in Schonbach. He was a gifted musician, and when he started playing, a crowd gathered to enjoy his music. The German POWs came up to listen along with some of the townspeople. I didn’t speak German well enough at that time; otherwise I’d have said, “Come listen to the music.”

I asked him to play the most beautiful war song ever created. It was composed in World War I. Part of the verse is, “She comes there, and she waits at the gate for a soldier who’s not coming back.” It hits you right in the heart. It’s called “Lili Marlene.” My friend knew it and he could really play it well.

Going Home

At some point before we left for home, we got a vacation, which was in Nancy, France. Finally we were at a place where there were no longer prisoners or bombed-out towns staring at us. We were starting to feel “normal” again. There was talk among the guys that many of us would not be going home because the war with Japan was still going on. The Army was waiting to see if reinforcements would need to be sent to the Pacific for the invasion of Japan.

Many of our veterans who had fought in North Africa and Sicily had already left us since they had enough points; you needed 100 to be sent home. Many of us who were drafted at their 18th birthday only had 40 points. We had only seen 11 months of action, where many of the guys that fought in Sicily and North Africa had seen close to 30 months of action—unbelievable.

Fortunately, Japan never happened for us. When I got home, I did not talk much about the war except with others who had served. I stayed busy with college, work (engineering), family, and friends. I married Louise in 1952. Once I got married and had a family, I tried to stay focused on those things and tried not to think about the war.

I was not real successful at night. I woke up many nights in a cold sweat, thrashing and yelling. I used to scare the heck out of my wife. Once I retired, I spent more time researching the war, finding out what was really going on, and remembering what I did. I talked about the war to everyone, and drove my family crazy. I went to retrace the steps of the Big Red One in Europe around the 50th anniversary of D-Day. That was the best time to start my recollections.

It was impossible as a 19-year-old to have a complete perspective of the war, knowing where we were, sometimes what day it was, what we were doing, or where we would go next. We couldn’t write things down and weren’t told too much in case we were captured.

As I review my recollections, the stories that are clearest are the ones that don’t involve the battles. I have spent so much time suppressing the “bad stuff” that, at 90 years old, I can’t actually remember many of the details of much of the action that I was in. I do still remember the terror, though.

Thank you for this story. I found it to be the best one I have ever read in your fine magazine. It brought back many memories of my own father even though he was a fighter and bomber pilot in the Army Air Force, and only told us the funny stories that happened to him. When traveling in a bomber he said in the parachute rack there was one with a large X painted on it. In case they needed to bail out you didn’t grab that one since it was where they stored their booze bottles. I miss him very much.