By Kevin M. Hymel

“DON’T WORRY, GUYS––the Airborne is here!” shouted Private Howard Buford to the worn-out GIs he and his fellow paratroopers passed on the snowy road through Bastogne in the early hours of December 19, 1944.

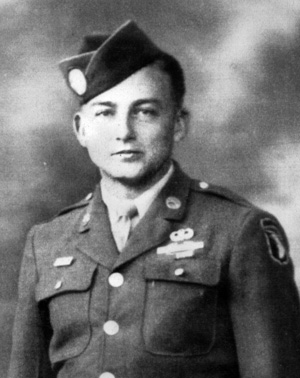

Buford, a paratrooper with the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, had never before been in combat, but he felt his unit was the toughest in the world and was about to teach the Germans a lesson.

The paratroopers halted at a building. “Why are we stopping?” a frustrated Buford asked his friends. They simply told him to wait. Buford and another man, who together manned a machine gun, found a foxhole and dropped in. As they set up their weapon, three German artillery rounds screamed in and exploded around them. Buford immediately lost his cockiness. When the dirt settled, he popped his head up and said, “I can go home right now!”

Home for Buford was East Los Angeles, California, where he lived in an apartment with his mother and younger sister. A high school graduate, Buford was working at the local Lockheed plant building P-38 airplane fuselages when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. He and a friend immediately tried joining the U.S. Army Air Corps, but Buford failed because he was color blind.

The Air Corps, however, was still interested in him. It wanted him to be a subject for tests to find a cure for color blindness; he submitted himself to months of tests while technicians in Santa Monica distorted his vision as they tried to cure him. Frustrated that almost all his buddies had entered the service while he served as a guinea pig, Buford left the program and tried to enlist, but his status as a defense industry worker gave him an unwanted exemption.

Buford learned that his only way into a uniform was to quit his job and sign voluntary induction papers at his draft board. He did, but nothing came of it. After months of waiting, he went to the induction center and raised hell. “I used profanity,” he recalled. A few days later, he arrived home to see that his mother had put his acceptance papers in front of his door. It was May 1943.

Buford volunteered for the infantry at the Arlington Reception Center, located at Camp Anza, California. “I figured it made sense,” he said. “I had been hunting all my life.” However, because he had scored well on the intelligence test, Buford found himself and six other inductees sent to the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), in Texas, where he spent three months.

The ASTP was established by the U.S. Army in December 1942 to identify, train, and educate academically talented enlisted men at colleges and universities across the country to become technically proficient officers. After basic training, Buford and his fellow ASTPers traveled to Iowa State College to study engineering. “No one ever told me I was smart,” said Buford. “I just screwed off in high school.” He spent his time taking test after test. “I was working so hard at it, but I was hanging on by my fingernails.”

However, heavy casualties suffered in the winter of 1943-1944 caused a critical shortage of infantrymen and resulted in the ASTP program being terminated in February 1944. Anticipating much higher casualties following the planned Allied invasion of France, the War Department required more infantrymen, not engineers. In early 1944, the Army sent all ASTPers to combat units as replacements. Buford was sent to the 97th Infantry Division at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, which did not impress him. He considered the unit unfit for combat and wanted out.

Buford and some friends asked their first sergeant if they could join the Airborne. The sergeant tried to keep them from filling out their applications. Once they completed the paperwork he stalled them again from taking their physicals. They were eventually rejected because too much time had passed between the application and the physical.

Finally, when the 97th Division moved to California, Buford again asked his platoon sergeant, whom he had repeatedly pestered, if he could transfer out of the unit. “Goddammit, Howard!” the sergeant blurted out, “I’m tired of your bellyaching! I’ll send you out with the next group of replacements.”

The sergeant kept his word. Buford was soon sent as a replacement to New York City. After only one night there he boarded the HMS Mauretania for a trip across the Atlantic. The ship was so fast it did not need to travel in a convoy. Buford never saw any Allied ships close to the Mauretania until it neared port in Ireland in mid-September 1944, three months after D-Day. With its deep draft, the Mauretania could not land in France and had to dock at Liverpool in western England.

The men were then sent to a replacement depot where, the next morning, hundreds of GIs assembled before an outdoor stage. Several officers with 82nd and 101st Airborne Division shoulder patches took the stage and asked for volunteers.

“My two buddies and I rushed down there,” said Buford, “and stood in line.” Buford’s two friends went to the 82nd Airborne, and he was assigned to the 101st—the “Screaming Eagles.”

The two American airborne divisions had distinguished themselves, albeit with heavy casualties, during the Normandy invasion on June 6, 1944, and then again during Operation Market Garden in September 1944, when they jumped behind German lines in Holland to capture key bridges over the Rhine River—an operation that ended in failure. Along with the U.S. Rangers, the airborne divisions were seen as America’s elite combat troops, and Buford wanted to be a part of them.

Buford next traveled to Camp Hungerford near Reading in southern England for paratrooper training, which greatly differed from infantry training. “They’re not trying to get you into shape,” said Buford, “they’re trying to make you quit.” A cadre of six paratroopers, who seemed like body builders to Buford, pushed the men to their limit.

One of the paratroopers led the volunteers in jumping jacks. “You did jumping jacks till you thought you’d fall over,” Buford recalled. Then another paratrooper would show up and put them through their next exercise. If a volunteer did not perform fast enough, the paratroopers would let him know. “Do you have shit for blood??!!” they would yell. “What’s wrong with you??!!”

The volunteers went for runs on narrow paved roads for miles with a truck following. If anyone could not continue, into the truck they went. Some nights the cadre of paratroopers would go out drinking, come back at midnight, wake the men up, and send them out running.

Sometimes an officer wearing no rank would show up and ask the volunteers a question. If anyone responded without saying “sir,” the officer would shout, “Get down and give me 50 pushups!” Some men did not last long. If anyone said, “I want to quit,” they were gone in less than an hour. “They got them right out of there,” stated Buford.

After about a week of physical training, the men began parachute training. They started out learning how to pack their parachutes. After some jump training from platforms, it was time to leap out of real planes. A few soldiers quit during the first drop, but not Buford. “I wanted to be a paratrooper so badly, by the time I got in the plane, I wanted to go.”

The jump drill was always the same: 18 men would sit in two rows of seats inside the C-47s while a sergeant stood in the open door. When the red light by the door lit up, the sergeant shouted, “Stand up and hook up!” The men stood up and hooked their static lines to an anchor line cable that ran the length of the fuselage.

Next, the sergeant yelled, “Equipment check!” and each man put his hand on the parachute pack of the man in front of him and made sure that it was packed tightly, then tapped him on the shoulder and told him it was okay. “I felt sorry for the officers,” said Buford. “They were at the front.”

When the sergeant shouted, “Move up and stand in the door!” an officer put his hands on the outside of the doorway and looked down. “There had to be a certain trepidation,” said Buford, who made the first two jumps without a problem. The third jump was the worst. “By then you had time to think about it.”

Buford made his five jumps, qualified for his jump wings, and was assigned to 1st Platoon, Easy Company of Colonel Julian Ewell’s 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment. He and other replacements flew to France and arrived at an old French barracks in the town of Mourmelon le Grand in late November. When the unit’s veterans arrived from the fighting in Holland, Buford got along with them immediately.

Buford made friends with 34-year-old Ray Carangio, who had been a carnival boxer. Challengers could win five dollars if they could last three rounds with him.

Buford was assigned to be a crew member on a M1919A6 Browning machine gun, a belt-fed, .30-caliber light machine gun with a bipod attached to the end of the barrel and a removable rifle stock. He was teamed with a veteran of the Normandy and Holland campaigns.

On the frigid night of December 17, Buford was standing guard duty when the sergeant of the guard told him to go get some sleep. Buford did, but someone woke him at 4:30 and told him to get his combat gear––they were going up to the front. Suddenly, everyone was up and scrambling for equipment. An hour later, flatbed trucks with side panels and removable tailgates rolled up to the barracks. Buford drew ammunition and climbed onto the back of a truck.

One of his friends returned from an all-night pass and climbed in wearing his class-A uniform. Another friend, from the regimental band, climbed in without a rifle. In combat, the band usually guarded the regiment’s equipment, but this soldier did not want to be left behind. Men packed into the trucks until someone installed the tailgate to keep them from falling out. The trucks then took off, driving all day and into the night to reach the small Belgian town of Bastogne.

Two days earlier, three German armies had broken through the U.S. First Army lines in Belgium and Luxembourg. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, acted quickly, sending two armored divisions into the maw as well as his strategic reserve, the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions. The 82nd would fight in the northern section of the bulge, while the 101st arrived outside Bastogne in the south.

The trucks drove the men in darkness through intermittent snow and rain, yet Buford could not recall being cold. He kept warm with long underwear, olive-drab wool pants and shirt, a winter overcoat, and jump boots. “Or maybe it was because there were so many of us in that truck,” he said.

The trucks parked outside the village of Mande St. Etienne, west of Bastogne, and the men piled out. Colonel Ewell’s 501st was the first element of the division to arrive, and the men headed northeast to engage the enemy while the other regiments spread out to man the perimeter.

A sergeant told the men to find a place to rest for a while. Buford lay against a tree and closed his eyes. When it got light, the men formed up and marched through Bastogne. “There were no other troops in front of us,’ recalled Buford. “People were cheering and clapping as we marched through.”

That’s when Buford saw the worn-out infantrymen, probably from the 28th Infantry Division, who had been fighting the German juggernaut for four days straight, and he told them not to worry—the Airborne was here. Soon after, three enemy artillery rounds cured him of his overconfidence.

Buford’s platoon reached the woods near the village of Bisory and pulled back to form a line in the middle of a sloped field. The two sides settled into static positions as the Germans now surrounded Bastogne. In the blinding fog and snow, the 501st paratroopers and the Germans patrolled each other’s lines, probing for weaknesses. Buford and his fellow machine gunner dug their foxhole at the bottom of the slope. It was not long before the Germans tested the American line.

The Germans opened fire with small-arms weapons. Buford could not see anything at the base of the hill, but he could hear American and German machine guns firing. “American machine guns went ‘put-put-put,’ while German machine guns went ‘ftttttt!’” he recalled. “The firefight atop the hill was only 200 to 300 feet away.” The paratroopers repulsed the probe, but the Germans captured a paratrooper in a foxhole next to Buford’s. “I don’t know if he was killed or not.”

Buford and the rest of Easy Company occupied a forested area with dirt roads. The restrictive terrain dissuaded the Germans from using tanks and armored vehicles. As a result, squad- and platoon-sized combat patrols clashed continuously in the woods.

For the next seven days, whenever the Germans probed the line the Americans greeted them with fire. At one point, Buford lost his machine-gun partner, possibly from frostbite, and had to operate the weapon by himself. When the Germans attacked, he fired where he saw flashes. “I seldom saw someone to aim at,” explained Buford. “It was mass confusion; I didn’t watch for detail.”

The continuous German artillery and mortar shelling eventually took a toll on Buford’s nerves. “When we would get a chance to eat, I would get away from my foxhole and throw up.”

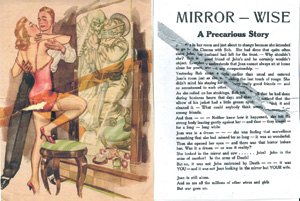

But the shelling was not always deadly. One day an artillery shell exploded over a field near Buford’s platoon, and sheets of paper—German propaganda leaflets—fluttered to the ground. Men broke cover and retrieved some of the sheets. They had a picture of a woman kissing a man in civilian clothes. The message: This is what’s happening at home. “They didn’t damage our morale at all,” laughed Buford. “We loved them!”

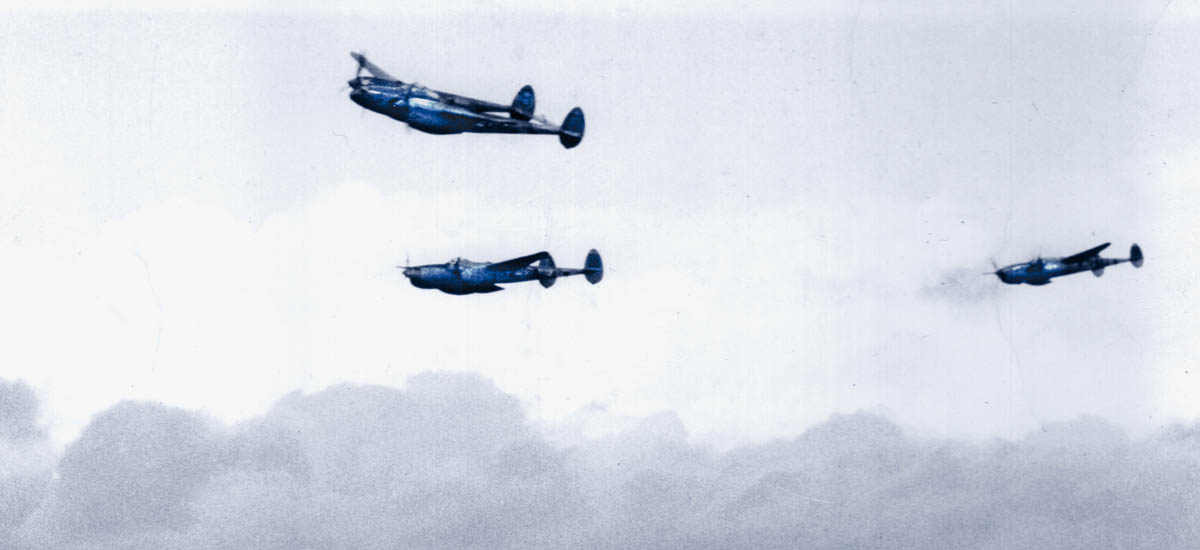

Buford’s platoon received some artillery support, but the American gunners had limited ammunition; the men relied on their mortars for immediate support. Fighter planes tried to fly under the low-hanging overcast but withheld their fire when they could not find the Germans.

When the fog and clouds finally cleared, the paratroopers laid out fluorescent orange panels to mark their forward positions and prevent being hit by friendly fire. American fighters and fighter bombers roared in, blasting away with machine guns and rockets as Buford and his friends, standing behind haystacks, watched the show.

“Thunderbolts came in so close you could throw a rock and it would hit them,” he said. Although C-47 Skytrain transport planes parachuted supplies into Bastogne, Buford did not recall ever seeing them, only hearing about them from fellow paratroopers.

German planes strafed Buford’s platoon a few times, but the men simply ducked into their foxholes. “It was a reflex action,” he recalled. “The safest place was on the ground.” Despite the strafings and probes, the men never believed the Germans would overrun them. “There was nothing we were worried about.”

Life in the cold and snow and ice proved miserable, though. One night, the men pulled back far enough to where they could build a bonfire. They stood with their backs to the fire, which melted the snow off their Army overcoats, soaking them in the process. When they turned around to warm their hands, their backs froze.

If the men had time to sleep, a truck would deliver their sleeping bags at night. In the darkness the men felt for their bags. Each would use a different kind of string or knot to recognize it by touch.

But the warmth of the sleeping bags brought a new problem. “My feet would hurt so bad as they thawed out,” said Buford, who had to bang his feet against the side of his foxhole to relieve the pain. “I’d cry, it hurt so bad, then I’d say, ‘Howard, you can’t cry.’”

When the officers were issued their alcohol ration, Buford’s lieutenant shared his with the men. Another lieutenant did not. One of Buford’s friends, a known alcoholic, watched that lieutenant pack his bottle into his bag one morning. When the packs were delivered that night, the friend felt for the lieutenant’s bag and stole his bottle. “This guy crawled in a hole and got drunk,” recalled Buford. “We covered for him when the officer came around.”

To eat in the pitch-black night, the men formed a line, putting a hand on the man in front before walking to the rear. Buford grew to hate the Army’s K-rations, foods that did not require cooking. They included cheese, meat, crackers, chocolate, and cigarettes.

“The first time you ate them they weren’t bad,” he recalled, “but you couldn’t eat them three or four days straight. They were terrible.” Buford and his comrades eventually resorted to eating only the K-ration chocolate bars.

Buford and his friends picked out a house in which to keep warm. The family stayed in the basement, rarely coming up. When the paratroopers first arrived, Buford stuck his frozen boots into the kitchen oven, but as the boots dried they shriveled up, forcing him to walk with a limp. It was worth it. “You’re so desperate to get warm,” Buford recalled. “It just shows you what young guys can handle.”

One day the paratroopers and the family made pancakes out of some flour, but the results were less than ideal. “They were not really pancakes,” said Buford.

On December 22, Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, the 101st Airborne’s acting commander during the defense of Bastogne, famously rejected a German surrender demand with one word: “Nuts.” Word quickly spread throughout the front lines. “Everyone laughed,” quipped Buford. “We were a first-class combat unit. We never thought of surrendering.”

Christmas came and went without notice. When German prisoners were captured, the men would pass them off to someone else. During one night probe, a paratrooper captured a German and brought him over to Buford and his fellow machine gunner’s foxhole. The German sat in the snow with his arms raised as the four men waited for sunrise. Every time the German tried to put his hands in his pockets, his captor stopped him. Buford felt sorry for the German but the paratrooper would stick his rifle in his gut and say, “Hands up!”

When the sun rose, the paratrooper took the prisoner to the rear, and Buford noticed a German “potato masher” hand grenade where the German had been sitting. “He had been trying to get at it all night.”

Before one patrol, a chaplain, possibly the 501st’s Catholic regimental chaplain Francis Sampson, showed up to offer a prayer for the men. While the soldiers gathered around the chaplain in the cold and bowed their heads in prayer, Buford sat by himself under a tree. He had not liked his introduction to religion as a child, when his father took him to revival tent gatherings where “born again” people rolled around in the sawdust.

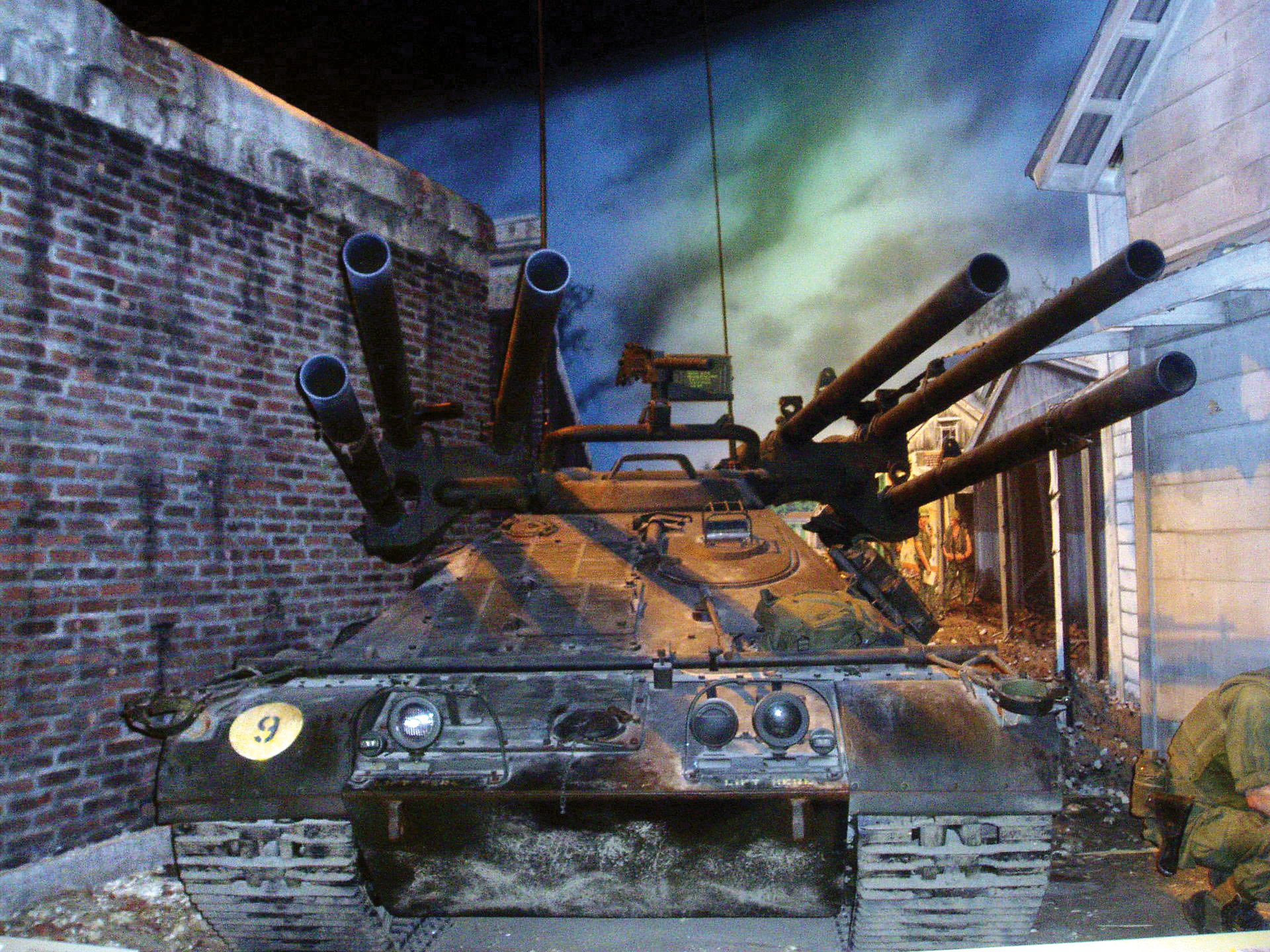

On December 26, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third U.S. Army broke the German siege and the momentum swung to the Americans. A row of tanks rolled up to Buford’s platoon, stopped in front of the forest, and fired into the tree line. With the Germans suppressed, Buford and his comrades advanced into the woods.

“We hit the Germans,” said Buford, “and were pushing them back.” Radio operators called in artillery 300 yards in front of the company and worked it back. The paratroopers hit the ground when the shells exploded in the trees above.

After advancing all day, Buford’s unit pulled back. The fighting continued that way throughout the rest of the campaign.

Patton’s arrival also meant hot chow. It was brought forward at night in insulated Mermite containers, but the servers had trouble seeing the men’s mess kits in the darkness. “They would dump meat, potatoes, gravy, and Jello on top of each other,” said Buford. “We were so tired, we were just happy to have food. No one complained.”

Buford’s company continued pressing forward. One day, they advanced on the Germans through neat rows of trees. Buford opened up with his machine gun, but it jammed. He tried loosening the barrel but nothing worked. Finally, he propped it up against a tree and grabbed a rifle.

As he stepped into the next row of trees, he saw a German soldier about 100 feet away. “We both hit the ground and commenced firing,” he recalled. A buddy next to Buford screamed out, “I’m hit! I’m hit!” He had just taken a bullet in the leg. In the confusion Buford had no idea if they had killed or wounded the German.

Another time, Buford was speaking with a fellow paratrooper in the shelter of some woods. When they finished talking, Buford walked away. Suddenly, an enemy artillery shell exploded, tearing off the other soldier’s leg. Buford escaped unharmed.

On January 3, 1945, Easy Company again attacked through a snowy wood, led by an aggressive platoon leader. “Some of the guys worried that he would get us in trouble,” Buford recalled. Buford was moving up and back with his machine gun on the platoon’s left flank when a Sherman tank clanked up a dirt road about 20 feet away and turned the corner at a crossroads.

Suddenly, Buford saw an explosion. “A bogie [tank] wheel came rolling back, then the guys came back. The tank sergeant was cursing mad.”

Undeterred, Buford’s lieutenant and about a dozen soldiers advanced through the trees and reached the crossroads where German vehicles were firing on the rest of the company. One of Buford’s buddies, a bazookaman, was so afraid that he ducked his head into the snow.

The lieutenant grabbed his bazooka, took aim, and knocked out one vehicle. Then he reloaded, stood up, and knocked out the other. “There’s a guy that should get a medal,” said Buford.

The fight with the tanks, however, resulted in 23 Easy Company men being wounded; one later died from his wounds, and the brave lieutenant was later killed.

Like most soldiers, Buford was scared many times in combat. His worst experience came when crawling through a hole in the bottom of a wall near a pile of dead horses. The entire platoon had preceded him and his lieutenant. Suddenly, mortars came in.

“You knew when artillery came in by its sound and you could fall to the ground,” he explained. “Mortars come in a steep angle and fall straight down with a little wispy sound.”

The two men huddled by the dead horses until the mortars stopped, then they dove through the hole. Buford yanked his machine gun through, accidentally pulling back its firing bolt, cocking it. He then ran house to house through the town, spotting a dead German in the street when it happened.

“My hand was on the machine gun,” said Buford. “I moved my finger, and it went off right in my ear.” The accidental blast terrified him, and he froze momentarily out in the open before recovering his senses and headed for cover. Later, everyone ribbed him for the mistake.

After the month-long heroic stand against the Germans, the 101st was pulled off the line on January 17. Buford’s platoon moved several times and ended up near the town of Dariendorf (renamed today as Dauendorf), France, in a small family farm. He thought it odd that the outhouse stood close to the well. “I would have just drunk wine instead of ever drinking out of that well,” he said about the suspect water.

One day someone obtained a large cache of eggs and served them to the entire company. The men lined up for two eggs each. Buford and his buddies gobbled them down and went for seconds. When the eggs were exhausted, the men ate bread pudding. Buford gorged himself on the dessert, and by the time he made it back to the barn he felt ill. “I was sick all night long,” he said. “To this day I won’t touch bread pudding.”

In the last days of January 1945, the entire 101st Airborne was transferred to France’s Alsace-Lorraine region to support Lt. Gen. Alexander “Sandy” Patch’s Seventh U.S. Army. Buford and his comrades were billeted in a woman’s house near the town of Minnersheim on the Moder River.

“The lady treated us nice,” he recalled. One of the men gave her a crock of hog’s blood, and she made blood sausage for the paratroopers, which did not prove popular. “We choked down some of it just to make her happy.”

At the end of February, the 36th Infantry Division relieved the 101st, and the division returned to Mourmelon. While the men were happy to be back in a familiar area, Buford received an unenviable assignment: he had to search dead paratroopers’ duffle bags and separate personal items from government-issue (GI) ones. Personal items were sent back to the families. The most bothersome part of the job was seeing pictures and letters of his dead comrades. “Something about those personal items bothered me,” he admitted.

For fun, the men traveled to nearby Reims, the ancient seat of the French monarchy in whose cathedral its kings had been crowned. But the young men were not there for a history lesson. “They sold us rot-gut champagne,” recalled Buford, but the men didn’t care; they would drink and have fun. The next morning, after an hour of calisthenics and an hour’s run, “we were ready to go [drinking] again.”

On one sojourn, one of Buford’s buddies asked him if he wanted to join the Pathfinders—the paratroopers who jumped before the rest of the regiment and set up guidance equipment to ensure an accurate drop. Buford agreed and signed up.

Buford, his friend, and eight other hopeful Pathfinders were sent to Chartres, France, southwest of Paris, for training. Along with a group of French paratroopers they worked for three weeks learning to operate various pieces of signal equipment. “They jumped more than we did,” recalled Buford. While everyone else watched movies at night, the French jumped out of planes.

Buford and his comrades trained for a jump into Germany. “Our leaders were concerned about American prisoners of war,” explained Buford, “and were considering a jump around German POW camps.” But the call never came, so the men relaxed and enjoyed themselves. They spent their downtime playing volleyball and, whenever possible, escaping to the City of Light, where a pack of American cigarettes could net $20.

When Buford and his friends could not obtain a pass to Paris, they made their own. “I spent almost every weekend in Paris,” he said. Between the cheap alcohol and the pretty girls speaking broken English, he enjoyed himself.

One night on the Paris Metro, Buford ran into a lieutenant from the Pathfinders, whom he considered an alcoholic. Buford asked him where he was going, and the lieutenant explained that the military police had threatened to arrest him if he didn’t leave the city. He was complying.

While Buford trained, the war in Europe ended. He returned to the 501st, which had been driving into Germany. His friends told him about Germans who had thrown away their weapons and, not wanting to be captured by the Russians, happily surrendered to the Americans. The unit soon returned to Mourmelon but was almost immediately transferred to a remote area of Austria for occupation duty.

From there they went to Berchtesgaden in southern Germany, the site of Hitler’s “Eagle’s Nest,” where Hitler, Hermann Göring, Martin Bormann, and many other Nazi bigwigs once had their mountain resort homes, for more occupation duty. The British Royal Air Force had leveled many of the Eagle’s Nest structures, yet Buford managed to find a few souvenirs.

He spent the next couple of months traveling across Europe. First, the regiment returned to Mourmelon, from which “old-timer” paratroopers were sent home; low-point men like Buford were reassigned to the 357th Glider Infantry Regiment. Then the 357th returned to Austria for more occupation duty, and then back to France, but this time to the town of Sens, where there was little to do except drink, which led to fighting and gunfire.

“Some of the guys had shot French people,” said Buford. General Eisenhower arrived and addressed the men. While he complimented them on their victory, the real purpose of his speech was weapons. “Ike asked us to behave ourselves.” From now on, the U.S. Army would punish anyone found with personal firearms.

The Army had decided that if paratroopers still wanted to get their jump pay, they needed to make more jumps. “All you had to do was hop on a truck, go out to the airfield, pick up a parachute, and get on a plane,” said Buford. He enjoyed the higher altitude jumps more than the low ones he had made in training. “We had time to enjoy the ride down.” Buford and his friends went back again and again for more.

One gliderman asked if he could jump, too, so Buford and his friends sneaked him in. “He jumped like everyone else and eventually reenlisted as a paratrooper.”

With the war over and thoughts of preparing for civilian life surfacing, Buford took Army-sponsored classes in Nice, France; Brussels, Belgium; and in England. He studied English, algebra, and surveying, respectively.

Once he was taking a ship to England and slept in the bow near the anchor chains. When the ship arrived, it dropped anchor with a great clanging noise, and Buford, thinking a torpedo had hit, jumped out of his bunk and charged out of his cabin. “I was already running when I woke up,” he recalled. “It scared the hell out of me.”

While Buford studied surveying in England in November 1945, the Army deactivated the 101st Airborne Division. He and his comrades were folded into the 82nd Airborne and returned home on the Queen Mary. The ship docked in New York harbor, and on January 12, 1946, Buford marched in a victory parade down Fifth Avenue—the “Canyon of Heroes”—with the rest of the 82nd.

“Smile!” the people along the route yelled to the marching paratroopers, but they held their straight faces. Despite the warm reception, Buford said, “We were unhappy. We wanted to go home.”

Buford flew to Long Beach, California; he was discharged from the Army at Fort MacArthur in San Pedro but almost did not make it home. On the bus ride back to East L.A., the driver pulled the bus over and told Buford he had to pay again. The bus fares had changed.

“I told him to stick it,” explained Buford. When the driver told him to get off the bus, Buford told him, “I think we’re going to have a fight.” Fortunately, another rider intervened and told the driver to let it go.

Buford made it back to his mother’s apartment and immediately threw his uniform into a corner. “I couldn’t believe I was free,” he recalled. His mother picked up the uniform and kept it for him. He wanted to put the war behind him and get on with his life. Other friends returned from the war, and they would all hang out together, but they never talked about the war.

Shortly after his discharge, Buford visited an ice cream parlor in Whittier. He knew the girl behind the counter, Rita Lucille Davis, from before the war. Buford liked her but had no plans to settle down. However, he changed his mind and they married in 1947 and remained together for 50 years until Rita died in 1997. They had four sons, David, Russell, Thomas, and Scott. Buford remarried at age 80 to Betty Moss, who passed away in 2013.

Once Buford had settled back into civilian life, he took a highway engineer job with the California Department of Transportation and worked there for 32 years. He later owned four businesses, spent eight years as a drug and alcohol counselor, worked with the Cub Scouts, and served as the president of a local Little League baseball organization.

Today he enjoys his retired life in Ventura, California. Despite his eagerness to put the war behind him, Howard Buford now looks back fondly on his service. “The time at the front was not a bad time for me,” he said, “I’m proud of the guys I fought with.”

I never knew your story until I read it today. I was so close to a hero and never had a clue.We owe so much to all our veterans. I wish they would tell your stories to children in school- maybe they would appreciate this country more.