By Erich B. Anderson

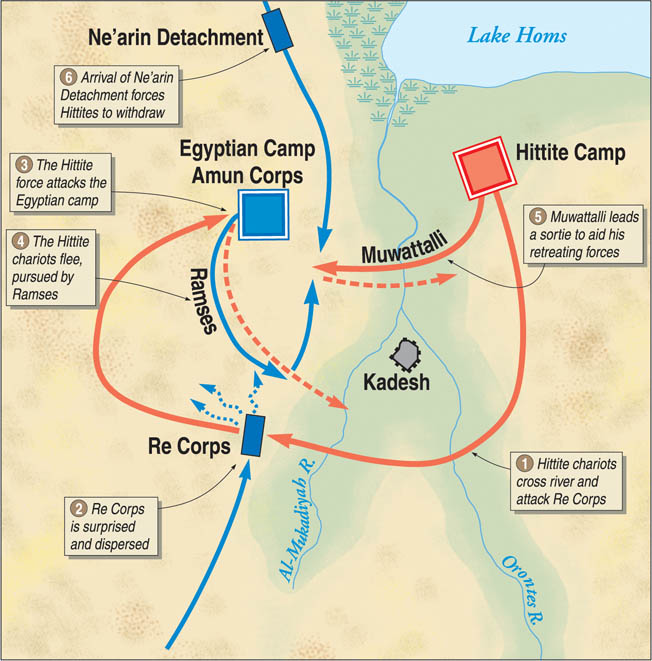

In the cold, early morning of a day in late May 1274 bc, the Egyptian troops of the Re corps were abruptly awoken with shouts, kicks, or nudges. Anxiety and panic rapidly spread among the half-asleep soldiers who were still fatigued from the long march the day before. As one of the four corps of the army of Egypt, the Re corps had traveled northward, toward what would be known as the Battle of Kadesh, and were miles behind the vanguard led by Pharaoh Ramses II. The commotion was caused by an urgent message that the pharaoh’s vizier had just delivered to the camp informing Ramses that a vast army of his formidable enemy, the Hittites, was stationed less than two miles away from his advance camp.

For this reason, the pharaoh desperately needed the Re corps to reach him as soon as possible to reinforce the Amun corps he led. If that did not occur, the numerically superior Hittite troops could easily overwhelm his much smaller force. In compliance with Ramses’ orders, the men of Re quickly mustered to continue their northward march, but it was too late. Many Hittite chariots had already traveled farther south and were hidden behind the nearby tree line to the east. They were primed and ready to assault the unsuspecting Egyptian soldiers as they tried to reunite with their pharaoh. The devastating attack of the Hittite chariots on the Re corps initiated the Battle of Kadesh, one of the greatest clashes of the ancient world.

The Kingdom of Egypt vs the Rising Hittite Empire

Centuries before the conflict between the Hittite Empire and the Kingdom of Egypt, the Egyptian state was forced to become a vassal of the powerful invaders known as the Hyksos. But the Egyptians managed to drive out their oppressors in the 16th century bc and reclaim their independence. This event marked the establishment of the New Kingdom era from 1565 to 1085 bc.

The Hyksos occupation of northern Egypt had a profound influence on the Egyptian kingdom. From then on, the Egyptians adopted an offensive strategy to prevent another foreign invasion on their eastern borders. Thus, the main focus of future pharaohs became the domination of the northern lands all the way to the region of Syria. Consequently, the military also rose in prominence within Egyptian society as it successfully conquered many independent states along the Mediterranean coast of Canaan and the Near East.

One of the most successful rulers of the new class of imperialistic pharaohs was Tuthmosis III. He led several military campaigns that secured Egyptian control over lands as far north as Ugarit by the end of his reign, including the strategic locations of Amurru, the Eleutheros Valley, and the city of Kadesh. With these vital possessions, the Egyptians were able to move their armies farther inland from the coast and retain their dominion over southern Syria.

If the Egyptians lost their access to the Eleutheros Valley and Kadesh, the northern border of their imperial territory would become extremely vulnerable to attack from the Kingdom of Mitanni, which was the most powerful state in the region. The Kingdom of Egypt, however, did not have the resources to garrison the troops necessary to maintain its domination over lands that were more than 600 miles away from its homeland. Therefore, Pharaoh Tuthmosis IV was forced to make a treaty with the ruler of Mitanni that established the border between the two Bronze Age superpowers in the second half of the 15th century bc. In the agreement, Egypt lost much of the territory won by the new pharaoh’s predecessors, yet he managed to retain control over Kadesh, Amurru, and the Eleutheros Valley.

The treaty brought peace to the two rival kingdoms for many decades until a new power arose in the region: the Hittites. These warlike people of Anatolia conquered the Mitanni in the 14th century bc. Their rise dramatically changed the territorial status quo in the region. Whereas the Egyptians considered the border established in the treaty with Mitanni as permanent, the Hittites did not feel the same way. Yet the Hittites were careful at first to avoid war with the Egyptians, focusing their attacks primarily on Mitanni until the kingdom was overtaken. Once they had conquered the Mitanni lands in southern Anatolia and northern Syria, the Hittites began taking Egyptian territory, starting with Kadesh.

The Egyptians were slow to react to the seizure of the strategic northern city. Initially, the Egyptians attempted to rely on the vassal ruler of Amurru to reclaim Kadesh. When that plan failed, Pharaoh Akhenaten sent Egyptian troops to attack the city. They also failed to take back Kadesh. Egypt’s fortunes diminished even more shortly afterward, for the king of Amurru changed sides and pledged his loyalty to the Hittite ruler. Since Hittite princes directly ruled over the Syrian cities of Aleppo and Carchemish with their own troops under their command, the ruler of Amurru decided it was better to side with such a dangerous force nearby rather than the Egyptian kingdom that was hundreds of miles away.

The Reign of Ramses II

Following the controversial reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten and that of his son, Tutankhamun, Egypt was effectively ruled by three different generals. None of these military commanders was able to reclaim the important imperial territories of Kadesh and Amurru. But when Pharaoh Ramses I came to power, a new line of kings was initiated, known as the 19th Dynasty. Ramses’ successors were fully aware of the lost Syrian lands and were determined to win them back by any means necessary. Sety I led a campaign to the north during which he not only managed to seize Amurru and Kadesh, but also invaded Hittite lands and defeated the Syrian vassals of the Hittites on the battlefield.

A major reason for the success of the new pharaoh was that the Hittite king was preoccupied with threats on his eastern border by the resurgent Assyrian Empire. Regardless of this, Sety’s gains were short-lived, for both Kadesh and Amurru fell back into the Hittite fold even before the pharaoh had passed away. Yet his son and heir, Ramses II, was present during his father’s campaign, which had a major influence on the future pharaoh. Once he ascended the Egyptian throne, Ramses was fully committed to finishing his predecessor’s work in southern Syria.

Ramses II became pharaoh of Egypt while he was still in his mid-20s. Early in his reign, one of Ramses’ main goals was to emulate the great warrior pharaohs of the previous 18th Dynasty, especially Tuthmosis III. To achieve his goal, he instituted military reforms and prepared the army for distant campaigns. Furthermore, the young pharaoh showed his preference for northern conquests by transforming Avaris, the old capital of the Hyksos, who had previously conquered Egypt, into a powerful military center from which the army could more easily invade the Asian territories. Once rebuilt, he named the new great city on the eastern delta Pi- Ramses.

The Two Great Armies

While Ramses made changes to the army and had Pi- Ramses constructed, his Hittite rival did not remain idle. King Muwattalli II already had fundamentally changed his empire by transferring the imperial capital from Hattusa in the north to the newly established city of Tarhuntassa in the south. The relocation of the royal city served two purposes. First, it allowed Muwattalli to concentrate his forces in the south in preparation for the inevitable clash with Ramses in Syria. Second, it ensured that the capital was not vulnerable and exposed to northern invaders while the Hittites dealt with either the Egyptians or the Assyrians. Along with the transfer of the imperial center, the Hittite king also reorganized the vassal states in the western and northern regions of the empire. By doing so, Muwattalli increased the manpower he had available to him considerably, so that he could go to war with a huge army composed of native and allied troops from as many as 18 vassal and allied states.

Even though Ramses did not need a pretense for war with the Hittites in Syria, the pharaoh ultimately received one in 1275 bc when the king of Amurru switched his allegiance back to Egypt. In the summer, Ramses gathered his forces and then led them north. The army marched first through Canaan and then along the coast of southern Phoenicia. The pharaoh used his troops to intimidate the vassal states and secure their obedience. Ramses apparently besieged Irqata, and this appears to have resulted in the wealthy cities of Tyre and Byblos submitting without resistance. With Canaan and Phoenicia firmly under his control, the pharaoh then led the army east through the mountains and into Amurru. Once the Egyptians reached their former vassal state of Benteshina, the king of Amurru formally gave his pledge of allegiance to Ramses. The pharaoh then led his army back to Egypt.

It did not take long for King Muwattalli to learn that Benteshina had defected, which not only put the city of Kadesh at great risk but also severely threatened the vital Syrian cities of Aleppo and Carchemish that did not have enough troops to stand against the full might of Egypt. Therefore, throughout the winter and into the spring of 1274 bc, the Hittite ruler mustered the army, calling in troops from all corners of the empire. Along with the native, allied, and vassal troops raised from within the lands of Great Hatti, Muwattalli also spent a substantial amount of silver to recruit a considerable number of mercenaries.

Hiring foreign soldiers increased the size of the army even further, but it resulted in a major drawback. Muwattalli had depleted his funds, which meant that many of his own troops went without pay in exchange for the promise that they could thoroughly plunder the riches of the defeated foe. The promise satisfied the Hittite troops leading up to the campaign, but it had the potential of creating disastrous consequences if their expectations were not fulfilled. Yet Muwattalli was willing to take that risk for he had managed to raise an enormous army of approximately 37,000 infantry, 10,500 charioteers, and 3,500 chariots.

Ramses also oversaw the preparations for the second northern campaign that would build upon the success of the previous year. The pharaoh assembled all four corps of the Egyptian field army. The first corps was Amun, composed of men recruited from the city of Thebes. Ramses personally led the Amun corps, which traveled with him and his royal entourage in the vanguard. The second corps was Re with soldiers from the city of Heliopolis. The third corps was Sutekh, whose troops came predominately from the pharaoh’s new military base at Pi- Ramses and from the rest of the northeastern Nile Delta region. The fourth corps was Ptah, raised from Memphis and the surrounding territory. The Egyptian army had approximately 16,000 infantry, 4,000 charioteers, and 2,000 chariots.

Most of the Egyptian troops fought for one of the four corps of the field army, though Ramses relied on other soldiers as well. Many foreign mercenaries and slave-soldiers from Canaan, Nubia, and Libya were included in the four main corps, though there were also some who served in their own units composed of their fellow countrymen. One of the most important contingents of foreign warriors was the Sherden, who so impressed Ramses with their martial abilities that they served in his royal bodyguard. The Sherden warriors were known for the unique horned helmets they wore and for fighting with straight, long swords. Furthermore, the pharaoh had also sent a detachment of elite warriors known as the Ne’arin from the land of Amor to travel ahead of the rest of the army so that they could reach Kadesh from the north. Yet, even with the foreign troops at their disposal, the Egyptians were still outnumbered by the Hittite forces.

The Egyptian Campaign Begins

In late April 1274 bc, Ramses led his army from Pi- Ramses and the eastern Nile Delta toward the fortress of Tjel on the border of the Egyptian homeland. From there, the Egyptians continued their march along the coast to Gaza. Ramses and the Amun corps traveled first, followed by the other three corps. All four corps of the field army traveled separately so that they could supplement their rations and provisions by living off the land. If such a large body of troops marched together they risked depleting the countryside, which would make foraging impossible.

One month later, the pharaoh and the Amun corps reached a mound known as Kamuat el-Harmel, which was a day’s march away to the south of Kadesh, and then they set up camp. After resting for the night, the Egyptians continued their march the next day, traversing the hill country and the forest of Robawi until they came to the Orontes River south of the town of Shabtuna. It is unknown exactly where the Egyptians forded the river; however, it was most likely near Ribla. After the long process of moving so much equipment, men and horses across the waterway, the army continued north toward the plain outside Kadesh.

Ramses and his men did not travel far before they came into contact with two Shosu Bedouin from the region, which were quickly brought before the pharaoh. The tribesmen claimed to have once served the king of Hatti but left the Hittites to side with Ramses and the Egyptians instead. The two men also gave the ruler of Egypt excellent news. When asked where Muwattalli and his Hittite forces were, their response was that once the king of Hatti heard that Ramses was marching northward, he refused to travel any farther south out of fear and decided to remain at Aleppo with his army. The pharaoh rejoiced at the news and then advanced to set up a fortified camp northwest of Kadesh.

While the Egyptian soldiers dug an embankment surrounding the camp and augmented the defenses with lines of infantry shields, Ramses ordered his scouts to survey the area. Shortly afterward they returned to the camp with two captured scouts of the Hittite enemy. At first, the prisoners refused to reveal any information. They were forced to endure a severe beating until they broke their silence. The Hittites were then dragged before the pharaoh to give him the bad news that the Bedouin tribesmen had tricked him. Muwattalli and the Hittite army were not 120 miles away in northern Syria, but only about two miles away from the Egyptian camp. With only the Amun corps with him, Ramses was desperately outnumbered and could easily be annihilated by the nearby Hittite forces. The pharaoh needed the rest of his troops immediately; therefore, Ramses sent his vizier to contact the Re corps as quickly as possible.

Striking the Egyptian Camp

Upon the arrival of the vizier to their camp, the men of the Re corps mustered as fast as they could and marched to the rescue of their pharaoh. The vizier then swiftly continued southward to alert the Ptah corps, which had not yet reached as far north as the town Aronama. The Re corps had the difficult task of crossing the Orontes River, which it rapidly forded. Some of the more mobile chariot crews may have even gone ahead toward Ramses’ position so that they could reach the pharaoh sooner while the rest of the men still had not made the crossing.

Once the rest of the Re corps had forded the river, they followed behind the chariots but still had to march 61/2 miles to get to the Amun camp. A fast pace was set by the officers, and the ranks were motivated and urged on by marching chants and battle trumpets. As the columns continued their march, the most visible landmark was the fortified city of Kadesh to the northeast. Kadesh dominated the landscape not only because it was built atop a great mound, but it also was bordered by both the Orontes River on the farther side and the Al-Mukadiyah tributary of the larger river on the side closer to the troops of the Re corps. Since moats were made on the sides not bordered by the waterways, the mound of Kadesh was virtually an island. Along the banks of the Al-Mukadiyah tributary to the right of the marching columns a thick line of trees, bushes, scrubs, and other vegetation marked its location but hid the waterway from view.

In the heat of midday, the Egyptian troops continued their march. Suddenly, cries of panic began to erupt from the right wing of the columns. Before most of the Re corps could properly react, the flank was brutally assaulted by a mass of heavy Hittite chariots. Many Egyptian soldiers were slain on impact by the long spears of the Hittite warriors and trampled under horses’ hooves and vehicles’ wheels. Those who managed to dodge the attacks fled in terror. While some Hittite crewmen were struck down or pulled off their chariots, many more Egyptians were killed in the surprise attack. After the Hittite heavy chariots had ripped through the Re corps, the drivers swung their vehicles wide so that they could turn north toward the true objective, the pharaoh and his camp.

The charioteers at the front of the Re column who were not attacked directly saw the Hittite vehicles wheel about and head in the same direction as their march. Once this was realized, the Egyptian chariots drove off as rapidly as possible and a race ensued. One side rushed to warn Ramses. The other desired to take him captive and plunder his camp. The rest of the Re troops, especially the infantry, scattered in all directions, and the corps completely collapsed. Meanwhile, the Amun soldiers in their camp were on high alert behind the defensive shield walls and embankments. The guards keeping watch spotted the two groups moving quickly toward them and noticed that one was a lot larger than the other. The smaller group of Egyptian chariots reached the southern end of the camp first, and the charioteers shouted warnings of the impending attack. Soon afterward, the heavy vehicles of the Hittites slammed into the western shield wall.

Even though Ramses and the Amun corps were alarmed by the news of the proximity of the Hittite army, they never would have suspected that an attack would come so soon and from the west. Pitched battles between great states had never before been conducted with such surprise and deception. Therefore, some of the Egyptian soldiers managed to quickly grab their weapons and run to reinforce the guards stationed there. However, their numbers were not sufficient enough to repel the coming onslaught. The Hittite chariots managed to break through the camp’s defenses, but the numerous obstacles in their path then slowed the vehicles considerably, allowing the Egyptians to make a counterattack. Taking advantage of the slow-moving, vulnerable crewmen, the Egyptians dragged a number of them off their vehicles and killed them with spear thrusts and slashes from the lethal, curved khopesh sword. Ultimately, the Egyptian assault did not deter the Hittite momentum, for their morale was still high from their success thus far. As more enemy chariots flooded into the camp, the crews in the front began plundering the enemy camp rather than exploiting their penetration by slaying vulnerable Egyptian infantry.

While the pharaoh’s bodyguards rushed to protect his family and household staff, Ramses armed himself for battle. The pharaoh then gathered any chariot crews able to fight and led them out of the eastern entrance to swing around and strike the attacking Hittites, even though the Egyptian vehicles were outnumbered. The Hittite heavy chariots had lost much of their cohesion in their lustful pursuit of plunder and were considerably vulnerable to the Egyptian counterassault. Smaller and more mobile than the heavy Hittite vehicles, the Egyptian chariots could turn at much sharper angles. The Egyptian charioteers used the composite bow as their primary weapon as opposed to the long spears of the Hittite crewmen. Unlike the stave bow used by their Nubian contingents, the Egyptian composite bow could fire at much greater distances. When used by skilled archers, the weapon was accurate up to 60 meters and still effective at 175 meters.

Once within range, the archers of the Egyptian chariots rained arrows down upon the clustered groups of Hittite crewmen. The missiles struck many before the Hittites could turn their vehicles and face the sudden assault in their flank and rear. However, even when the Hittite chariots advanced toward the Egyptian attackers, they could not get close enough to engage in combat before they were shot down. The design of the heavy Hittite chariots was ideal for shock tactics, but the large size of the vehicle and its three-man crew meant that it moved much slower and was less maneuverable than the Egyptian model. In contrast, the smaller Egyptian type of chariots only carried two men, turning the vehicle into a mobile firing platform ideal for ranged combat rather than to crash into enemy infantry lines. To augment the Egyptian chariot crew, a fleet-footed soldier was assigned to run alongside the chariot and assist the crew in combat. Hittite crewmen were armed with composite bows like their Egyptian counterparts, but the weapon was not used as much and was not nearly as important as it was to the Egyptians.

After witnessing the fate of their comrades who had tried to close with the Egyptians, many of the Hittite charioteers decided to retreat from the enemy camp. Before long the entire Hittite force was in full withdrawal. The battle was not over for Ramses and his men, though. The pharaoh led them in hot pursuit of the fleeing enemy, continually firing arrows. Although many of the Hittite chariots dispersed, making the individual targets harder to hit, their horses were spent, which caused them to move much slower than the fresh steeds of the Amun corps’ chariots. The Hittite drivers continued to spur the horses on in desperation, hoping to make it back to the safety of the other side of the Al-Mukadiyah tributary as fast as possible.

Flight to the River

King Muwattalli of Hatti was able to view the confrontation from his vantage point near Kadesh and watched in frustration as Ramses and the Egyptians were routing his elite chariot force. The Hittite king quickly came to the realization that if the Egyptians were not stopped they would most likely kill nearly all of the chariot detachment that had been sent against them before the Hittites could cross the tributary. Therefore, Muwattalli turned to those around him, including aristocratic warriors, members of the royal family, and allied leaders, and ordered them to ford the Orontes River to make a diversionary attack on the Egyptians. The ad-hoc force immediately followed the king’s orders and crossed the waterway as fast as possible.

Once on the other side of the river, the elite chariot crews headed straight for the Amun camp while Ramses and the bulk of the Egyptian vehicles were still away to the south chasing their comrades. At that point, the members of the Egyptian royal household, which included Ramses’ young sons, were even more vulnerable than they were during the first Hittite attack. The Sherden and the other elite warriors of the royal bodyguard were ready to die fighting to protect the Egyptian princes, but the sacrifice was unnecessary. The Ne’arin had finally appeared in the north after traversing over Amurru through the Eleutheros Valley, ready to enter the battlefield at the most opportune moment for Ramses and the Egyptians. The Ne’arin chariots rushed to the aid of the Amun soldiers still in the camp and unleashed a barrage of arrows upon the royal Hittite charioteers. Like their Hittite comrades, the ad-hoc chariot detachment could not withstand the vicious volleys of missiles, so they fled back to the Orontes River.

While the second Hittite chariot force was racing toward the river, Ramses and his men had returned to help the Ne’arin completely rout those Hittite vehicles as well. The Hittites that managed to reach the Orontes frantically threw themselves into the water to escape the slaughter. Those who fell off their chariots before reaching the river were slain by the Egyptian infantry, who had followed behind their chariots to rejoin the combat. Corpses were robbed of their possessions. More grisly trophies were taken as well, including the severed hands of the deceased enemy soldiers. These body parts not only served as prizes that backed up the foot soldiers’ ferocious reputation on the battlefield, but also were a way to keep track of the number of enemy casualties.

The Hittite crewmen that were lucky enough to reach the river were far from safe. Numerous men could not swim across and drowned. These unfortunate souls were either pulled down deeper into the water due to their heavy armor or the current swept them away. Even the Hittite prince of Aleppo nearly drowned, but he was ultimately pulled out of the water by his comrades. Many of the royal and aristocratic warriors of the ad-hoc detachment and the first group of chariot attackers were not so fortunate.

Aftermath of the Clash of Chariots

The Hittite casualties included six army officers and four prominent chariot crewmen, along with two of Muwattalli’s shield bearers, the captain of the royal bodyguard, the king’s secretary, and two of his brothers. The chariot units had been thoroughly devastated, even though some of the crewmen managed to make it to safety. In contrast, the Hittite infantry units were more fortunate. They remained completely intact because they did not participate in the combat.

The Re and Amun corps of the Egyptian army took heavy losses as well. But the pharaoh was left in control of the battlefield. Furthermore, reinforcements in the form of the Ptah corps had finally arrived, followed by the troops of Sutekh later that same day. For fleeing from the battlefield and abandoning their ruler, Ramses likely had the Re and Amun soldiers severely punished in front of the rest of his army to set an example.

Ramses may have led his troops across the river the next day to attack the Hittite army near its camp, but this cannot be confirmed. Even if it did occur, it did not change the outcome. Due to the heavy losses of chariots, the Hittite army was significantly weaker in that aspect, but its infantry still vastly outnumbered the Egyptian foot soldiers. Regardless, the Egyptian accounts claim that the Hittite king begged Ramses for mercy and pledged to become his vassal. This is highly unlikely, though, for Muwattalli still held the city of Kadesh and did not give the Egyptians possession of it after the battle. The encounter resulted in a stalemate.

Since Ramses did not have the manpower to storm Kadesh, the pharaoh returned to Egypt with his army. Shortly afterward, Muwattalli moved into Amurru with his troops and captured King Benteshina for changing sides to support the Egyptians. The prisoner was then hauled off north to Hattusas in the Hittite homeland and was replaced by a new ruler, Shapili. Although exiled, Benteshina would eventually find favor with the brother and senior adviser of the Hittite ruler, Hattusili, and was later allowed to live in his northern capital of Hakpis.

With Amurru and the city of Kadesh back firmly under his control, Muwattalli turned out to be the true victor of the battle. The Great King of Hatti may have failed to completely crush the Egyptians with his enormous army, but that was unnecessary after he successfully prevented Ramses from taking any of his Syrian vassal states. Muwattalli followed up his success by marching south with his forces and invading Egyptian home territory. The Hittites first conquered Kumidi and the prosperous city of Damascus, which then allowed the Hittite king to seize control over the entire province of Upe. The king of Hatti gave the prestigious position of governing the former Egyptian land to Hattusili. After adding Upe to the firmly re-established buffer states of Kadesh and Amurru, Muwattalli was ready to return to the heartland of his empire.

Rebellion in Canaan, Peace With the Hittites

As Ramses and the Egyptians traveled through the cities of Canaan on their return journey home, they were jeered by their imperial subjects. Despite his failure to accomplish any of his goals, the pharaoh still entered Pi- Ramses in great triumph in late June 1274 bc. Trailing behind Ramses was a parade of Hittite captives and plunder taken after the battle to give the people the impression that Egypt was the sole victor of the conflict. The spectacular display may have worked on the Egyptians, but the Canaanite vassals were clearly not impressed by the performance of the Egyptian army at the battlefield near Kadesh. By the time Ramses and his forces had reached the eastern Delta city, rebellion had erupted throughout Canaan and Palestine.

Ramses was not the only one who had major issues to deal with after the battle, for Muwattalli’s success in Upe was followed by an attack from the powerful Assyrian Empire in the east. While Hatti and Egypt were preoccupied fighting each other, the Assyrian ruler Adad-nirari I exploited the vulnerability of the Hittite Empire by conquering its ally Hanigalbat. By doing so, the Assyrians became an even greater threat on the eastern border of Hatti territory.

Despite the revolts that broke out across his subject territories, Ramses began to immediately prepare for the construction of huge monuments to display his great victory at the Battle of Kadesh. Amurru and Kadesh may have remained lost to Egypt, but Ramses was much more concerned with showing his bravery and martial prowess for all to see rather than admitting to his failure. In the end, the pharaoh did his best to make sure that accounts of the confrontation were immortalized, for they were recorded not only on the Ramesseum, but also on the temples of Luxor, Abydos, Karnak, and Abu Simbel. In these impressive images and accompanying literary records, the battle was depicted as a much grander engagement, and the pharaoh’s role in it was exaggerated. In following Ramses’ instructions, the Egyptian accounts implausibly claimed that the pharaoh singlehandedly defeated thousands of Hittite chariots.

Once the construction projects were underway, Ramses spent the next few years of his reign ending the rebellions in the north and reestablishing his rule over Canaan, Palestine, and Syria. After the revolts were put down, the pharaoh moved on to reclaim Kumidi, Damascus, and the province of Upe. Ramses then copied the strategy of Adad-nirari by attacking the Hittites while they were distracted by threats from the Assyrian Empire. By 1269 bc, the pharaoh led his army eastward in a campaign to completely bypass the fortress of Kadesh and then invaded Hittite territory to capture the cities of Dapur and Tunip. With those Hittite lands in his possession, Ramses successfully cut off the city of Kadesh and most of Amurru from the rest of the rival empire. The pharaoh had finally achieved some semblance of the goal he had initially set. The ruler of Egypt may not have reclaimed its lost lands, but he had drastically decreased the importance of those territories.

Dapur and Tunip did not retain their allegiance to Egypt; they reverted to the Hittites once Ramses left. The pharaoh may have taken the cities several more times but never managed to keep control of them. For a decade tensions remained high between the Kingdom of Egypt and the Hittite Empire. Despite their mutual animosity, another major confrontation never occurred. The danger of Assyrian invasions and a power struggle over the Hittite throne prevented another major army, such as the one led by Muwattalli, from ever engaging Egyptian forces. As for the Egyptians, they did not have the logistical capabilities to invade and retain any lands in northern Syria.

In the long run, the Hittites could no longer hold up under threats from two fronts; therefore, in November 1259 bc, the new ruler of Hittite Empire, Hattusili III, reached out to Ramses, and the two kings formally made peace with a treaty. To strengthen the new alliance, the Hittite king allowed the pharaoh to marry his daughter. Ramses publicly stated how pleased he was with the union, which was a redeeming factor for the pharaoh when peace ultimately meant that he would never emulate his idol, Tuthmosis III, and reclaim the lost lands of Kadesh and Amurru.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments