By Volker Griesser

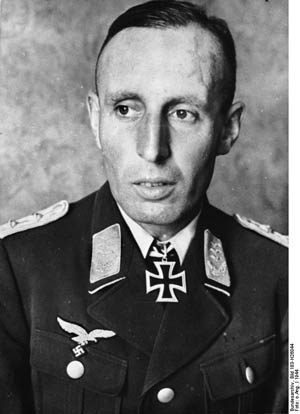

Background: Fallschirmjäger Regiment 6, under the command of Major Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte, had the fortune (or misfortune) to be stationed in Normandy at the time of the Allied invasion of France on June 6, 1944. In the first installment of this excerpt from Griesser’s book, The Lions of Carentan, two American airborne divisions—the 82nd and 101st—landed in the midst of FJR 6 and the desperate battle was on. In this second installment, the German parachutists have just been ordered to retake the important road-junction town of St.-Mère-église, which had been captured by American paratroopers.

A Reconnaissance Mission

Dietrich Scharrer, an Oberjäger [under-officer] in the 7th Company, recalled, “Around midday on 6 June, I received the assignment from our platoon leader, Leutnant von Socha, to lead a recon troop and gather information about the enemy [at Ste.-Mère-église]. We advanced from cover to cover, bush to bush, in the specified direction, intending to use our machine gun for fire support. At that point, we hadn’t seen anything of the soldiers on the other side.

“In this way we entered into a disastrous situation. Even before we got our machine gun into position, Obergefreiter [Private First Class] Walter Klute was pushing through a hedge and was halfway through when we heard a short burst of gunfire. Because Klute took a round directly in the chest, he was dead right away, our first casualty. We had established contact with the enemy; our assignment was fulfilled with this, and we pulled back. When we reported the strength of the enemy and his position to the company, Leutnant von Socha gave me a proper dressing down for having lost someone in our first deployment.”

Some of the 2nd Battalion were successful in breaking into the Americans’ positions. The U.S. units, however, were connected to one another via small, portable radios, so they could easily request fire support from mortars. The Americans soon brought down mortar fire on the 2nd Battalion positions, and the men of FJR 6 had to pull back to Turqueville [about four miles east of Ste.-Mère-église].

In the course of the night, Hauptmann [Captain] Rolf Mager [commanding 2nd Battalion] received tactical information from his recon units and formed a very clear picture of the numerical superiority of the enemy troops: The flanks and rear of the 2nd Battalion were threatened by American units, and in order to prevent his battalion becoming encircled and destroyed, Mager decided to withdraw to St.-Côme-du-Mont [11 miles south of Ste.-Mère-église].

That night, 30 American military gliders landed directly in front of 2nd Battalion’s positions, bringing supplies and reinforcements for the troops in Ste.-Mère- église. In the open field of the landing site, the Americans were easy targets for the Fallschirmjäger, who quickly overpowered them. The Germans took rations from the American supply boxes: fruit juice, chocolate, cigarettes, cans of meat, and everything that a hungry soldier could want.

Dietrich Scharrer remembers his experience of the engagement: “On 7 June, my group and I were supposed to join a scouting troop of the 5th Company. We found the 5th Company quickly; they lay well camouflaged in a bush behind an earthwork. I told my soldiers to be quiet and take position between the groups of the 5th Company. Then I understood what we had planned here. In front of us lay a wide field, on which American military gliders were landing. When the first [glider] touched down, fire from our gun barrels greeted him. It was a mean surprise for the Americans to have so much heavy fire rain down on them during the landing. Many of them paid with their lives; they must have suffered great losses. Afterwards we searched the field to haul scattered Americans from their hideouts. My group returned back to the 7th Company.”

Withdrawal From St.-Côme-du-Mont

On the morning of 7 June, the Fallschirmjäger broke away from the enemy and occupied a defensive position in front of St.- Côme-du-Mont. This move soon proved to have been the right decision, because scouts reported strong enemy units approaching from the direction of the “Utah” [Beach] section, and from Ste.-Mère-église toward St.-Côme-du-Mont. If they had stayed any longer in Turqueville, it would have cost FJR 6 a second battalion.

Meanwhile, Major von der Heydte had secured the area from St.-Côme-du-Mont to Carentan with two companies from the 3rd Battalion and brought 3rd Battalion/1058th Grenadier Regiment into deployment near Basse Addeville to guarantee the safe return of the 2nd Battalion/FJR 6. An energetic advance by American tank units, however, broke through the grenadiers’ defensive positions. The 9th Company of FJR 6 stabilized the grenadier unit’s front, and once again the Fallschirmjäger destroyed some enemy tanks with close-combat tactics.

The Americans now attacked the Fallschirmjäger positions around St.-Côme-du-Mont from the north and east. In a delaying battle, FJR 6 still managed to fight off the enemy assaults, but the danger of being encircled remained. A unit of American light tanks penetrated into the positions of the 3rd Battalion during the fighting. Obergefreiter Fischer managed to bring one of the vehicles to a halt with a Panzerfaust directly in front of the battalion’s command post.

Because the American ground troops had reported the position of the Fallschirmjäger to the naval artillery, FJR 6 troops by St.-Côme-du-Mont also received heavy fire from the sea. One element of uncertainty was the resilience of the subordinate army battalion, whose Georgian companies [Note: some “German” units were comprised of foreign troops, including those from the Caucasus state of Georgia] were given a particularly tough hammering by the Allied air attacks.

At first in smaller groups, later in larger ones, the Georgians trickled away from their positions and turned themselves over to the enemy. “After three days, no more Georgians could be found,” Major von der Heydte remembers in his memoirs.

In the meantime, enemy tank forces marched on Pont l’Abbé, a village northwest of Carentan. Further elements of the 3rd Battalion/FJR 6 were deployed to clean up the breaks in the line, but it turned out that a row of smaller towns and homesteads had been occupied by the Allies, and winning them back would only lead to splintering the forces of the 3rd Battalion. Major von der Heydte therefore announced the return to Carentan.

But he soon learned that his own troops, probably the company of the 191st Pioneer Battalion who had been stationed in Carentan until then, had blown up the northern bridge over the Douve. Now FJR 6 found itself in a pinch, with Americans in front of them and on their flanks, and cut off by the flooded areas behind them. Major von der Heydte did the only correct thing: instead of waiting until the Americans rolled up and destroyed the 2nd Battalion with their numerical strength, he ordered a retreat into the area south of the Douve.

In the morning, a heavy barrage of American field and naval artillery beat down on the ranks of the 2nd Battalion. The enemy increasingly used phosphorous grenades, which caused intense burns for their victims. With smoke grenades the Americans then laid out a thick obscuring curtain, under the cover of which their combat troops could sneak in and settle themselves in hedges and trees.

Dietrich Scharrer remembers, “With three submachine-gunners and Gefreiter [Private] Herbert Peitsch, who had a rifle grenade launcher, I was supposed to cover the withdrawal of the 7th Company. We spread ourselves wide across the position and waited until the order came to retreat. Then we slid slowly under cover into the trenches along the street.

“Suddenly we were under small-weapons fire from the left! I couldn’t make out the origin of the fire and therefore could not figure out the enemy’s positions. Gefreiter Peitsch ran across the street, sat down with his legs apart and began to bombard the tree line in front of him with rifle grenades. He was so calm while doing so, as if nothing could happen to him. But the way he sat there made him a perfect target for sharpshooters in the trees.

“On this day, for the first time, Gefreiter Peitsch showed stubbornness and cold-bloodedness on the front. He hit a sniper in the tree with a rifle grenade. The sniper fell out of his hiding spot and ended up hanging from a tree branch. Peitsch turned to me and said ‘Oberjäger, look at that—I feel sorry for him!’ Peitsch mastered situations like this with his rifle-grenade weapon. On his own, he shot up two Sherman tanks and died in the process. Posthumously he received the Ritterkreuz [Knight’s Cross] for this action.”

A March Through the Swamps

At the same time, the Americans succeeded in breaking through the defenses of 3rd Battalion/1058th Grenadier Regiment, and forced the remains of the battalion to flee. In mindless flight, the battalion was pushed back towards the west. The 13th Company’s position also came under heavy fire, as well as the regimental combat platoon deployed to protect them, the bicycle platoon, and the messenger section.

The powerful shells of the naval artillery caused great losses among the Fallschirmjäger and destroyed some of the heavy weapons that were so necessary to providing fire support. At 5:45 am, the Americans stopped the barrage but did not immediately follow up with their ground troops, so that the available elements of FJR 6 had a chance to regroup along the St.-Côme-du-Mont–Carentan road and place their remaining mortars into a secure reverse-slope position. Soon, however, the American infantry showed up and stormed the new defensive line, and were only pushed back in bitter close combat.

Nevertheless, the enemy succeeded in entrenching themselves on the western edge of St.-Côme-du-Mont and bringing further tanks into position. Because the Americans were now unhindered by German defenses on the coasts, they could land reinforcements of men and armor; this build-up led Major von der Heydte to the conclusion that the position on the road towards Carentan could not be held for long. The swamp between St.-Come-du-Mont and Carentan represented a formidable hindrance for the Allies, as FJR 6 could quickly take a new defensive position on the northern edge of Carentan.

Second Battalion/FJR 6, meanwhile, pulled back past Housville through the flooded fields and over a railway bridge towards Carentan. During this process, the battalion lost its heavy weapons, because these could not be transported across the swamp. Through radio contact with the 3rd Battalion, Major von der Heydte announced the arrival of the 2nd Battalion in the Carentan area. The support weapons of 3rd Battalion/FJR 6 were set up to cover the withdrawal route.

While the few mortars, submachine guns, antitank guns and 2cm anti-aircraft cannons could not match the firepower of the Allied artillery, Oberleutnant [1st Lt.] Pöppel’s company nevertheless managed to shut down an advanced command post with well-aimed mortar fire. The 3rd Battalion, however, also found itself under fire. The Fallschirmjäger regretted the beautiful sunny day, because the wonderful weather brought further air attacks, in addition to the harassing fire of the American big guns.

The 2nd Battalion needed longer than planned for the march through the flooded area. Wading and sometimes swimming, the Fallschirmjäger had to cross the swamp to then proceed along the railroad embankment. From their position on top of Elevation 30, they observed further landings of transport gliders near Ste.-Mère-église. Bomber fleets thundered above their heads, destined to unload their deadly cargo over the Vire River bridges.

The bicycle platoon, under the leadership of Leutnant von Cube, still managed to establish and maintain communications with the retreating 2nd Battalion.

Those from FJR 6 who were following Major von der Heydte through the swamp towards Carentan had as difficult a situation as the 2nd Battalion––further pieces of gear and equipment sank into the water. A handful of Fallschirmjäger who attempted to save the machine guns at least, drowned for their efforts. Sanitäts-Fahnenjunker-Unteroffizier [Medical NCO Officer Candidate] Hehle, an excellent swimmer, managed to save the lives of some of his comrades in the swamp.

When von der Heydte’s combat squad finally reached dry ground, the major found the 3rd Battalion already in position. His small troop was temporarily incorporated into an extension of the defensive line.

Low on Supplies

Shortly after 10:00 am, the pickets of the 3rd Battalion reported that the tip of 2nd Battalion/FJR 6 could be seen approaching through the path in the marsh area. The Americans also noticed the movement of the withdrawing Fallschirmjäger; they attacked the German troops, who were moving forward slowly and with difficulty because of the terrain.

Now the heavy weapons of the 3rd Battalion opened a devastating fire on the Americans, thus giving their comrades the chance to climb up the railway embankment and cross over the Douve River on the railway tracks. The 8th Company of the 191st Artillery Regiment even managed, by firing six anti-tank shells, to destroy the church tower of St.-Côme-du-Mont, in which the Americans had set up an observation post. The U.S. troops were apparently too surprised by the fire assault to cover the railway bridge with their own mortars or machine guns; therefore the 2nd Battalion succeeded in reaching the safe side of the Douve.

Leutnant Degenkolbe, the leader of the Pioneer [Combat Engineer] Platoon, stood ready to transport the men across the water with inflatable boats, but luckily this dangerous undertaking was not necessary.

By throwing up a curtain of fire, the 3rd Battery of the 243rd Anti-aircraft Regiment prevented low-flying enemy air attacks for the duration of the crossing of the railway bridge. A skilful feint prevented the American infantry from going after the 2nd Battalion in earnest. By running along the hedges and firing from changing positions, the men of the bicycle platoon and the regimental combat platoon gave the enemy the impression that the defensive position was occupied by strong forces.

By [a farm in the village of] Pommenauque, the recently arrived 2nd Battalion took up its position right away and defended the area against a strong American recon unit that wanted to work its way forward in the direction of the bridge to Carentan. The 6th Company under Leutnant Brunnklaus went after the enemy unit and destroyed it.

Immediately after his arrival, Major von der Heydte had Hauptmann Trebes inform him about the situation. The area west of Carentan was completely flooded around the Douve and therefore safe from enemy attacks; east of the city the ground was swampy and unfit for tanks.

The supply situation of the regiment was particularly worrisome, given the significant material losses it had suffered, especially in terms of vehicles and heavy weapons. FJR 6 also had to provide supplies for the units placed under them. Many of the ammunition and ration reserves were lost with the vehicles; furthermore, the fighting had led to a disproportionate use of ammunition. At the regiment’s special request, one of the ammunition storehouses, “Melon,” was assigned to them by the 91st Airborne Division.

The Waffen und Geräte Trupp (WuG; Weapons and Equipment) that showed up there found a well-marked and well-prepared storehouse that was, however, completely empty. The replacement storehouse “Mulberry” [not to be confused with the Allies’ two artificial Normandy harbors known as “Mulberries”], which lay 50 kilometers [30 miles] from Carentan, was in the process of being relocated, so no ammunition could be received from there.

One thing was clear as day to FJR 6: Carentan was the linchpin of the right wing of the Allied invasion army, because as long as the city was in German hands, the Allies could not unite their “Utah” and “Omaha” landing zones, nor push forward into the flank of the German defense.

Blowing the Taute River Bridge

Major von der Heydte had some of his troops go into position along the flooded areas by the Douve, west of the homesteads, over the northern and eastern edge of the city. At the same time some of the Georgian army volunteers who had recently arrived from the 635th Eastern Battalion were deployed to strengthen a rear position in the south of the city. Parts of the 2nd Battalion relocated at night to the eastern edge of Carentan because the forward-deployed observers reported American troops approaching the city from “Omaha.”

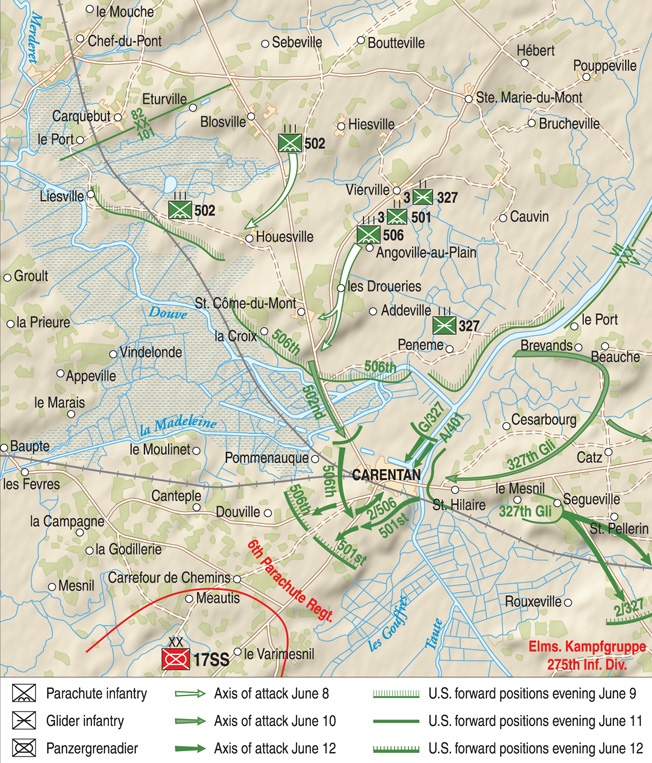

The Americans’ first goal, to take Carentan by midday on 6 June, had already failed, but it was expected that the Allies would commit everything to get the city under their control as soon as possible. Indeed, two hard-hitting and large task forces stood ready to storm Carentan, along with the 101st Airborne Division and the 1st Infantry Division.

Eugen Griesser [the author’s grandfather] remembers the early phases of the engagement: “Our group lay on the northern edge of Carentan in the first floor of a house. From there we looked onto the National Street, which gave us a clear view into the city, and all around there was a broad field of fire. To the left and right of the street, American soldiers were working their way forward; it was definitely a whole platoon sent to scout ahead. When our machine gun opened fire, they scattered and went under cover. A short time later, enemy fighter-bombers appeared and fired on the houses along the street.

“The Americans tried one more time to bring their recon troop into the city, but quickly discovered that their fighter-plane attack had not cleared us out of our position. It didn’t take long until their artillery opened up to shoot the way clear for them. Everything that you can imagine came at us: mortars, small arms, aircraft, even naval artillery from the sea. It went on and off like that for days.”

Carentan became the Cassino of the Normandy invasion front [the Allies’ drive northward through Italy stalled at Cassino in the autumn of 1943]. Like the old “Sixers” had done in Kirovograd, the men of this FJR 6 transformed every building into a fortress. They lured the Americans into traps, maneuvered around them and cut them off from their own lines. As soon as a U.S. combat unit believed it had secured one section, the Fallschirmjäger appeared from an unexpected direction and engaged them in crossfire. In a countermove, the enemy artillery, in tandem with the fighter-bombers operating during the day, turned the city into a landscape of ruins.

A group of engineers was assigned the task of blowing up the Taute River bridge, which led to the Carentan train station. Gefreiter August Gönnermann and his comrades took their positions along the bridge and began to wire the explosives. The importance of their task soon became clear, as a strong American force tried to take the bridge, which they believed to be unwatched, in a quick attack.

The Fallschirmjäger allowed them to advance to within close range, then opened fire on them and threw the Americans back. The commanding subordinate officer tried to set off the explosives with an electrical fuse, but because of a technical failure, this was unsuccessful. Despite the enemy fire, therefore, Gefreiter Gönnermann jumped out of his foxhole on the side of the street and set off all the explosions manually.

Just in time, and with a huge leap, he managed to get himself to safety as the charges exploded behind him. So thick was the smoke that only after a full five minutes could the Fallschirmjäger recognize that the destruction of the bridge had been successful. The cloud of dust that formed from the explosion proved that the task had been completed; the bridge was completely destroyed.

“Would You Surrender in the Same Situation?”

On the afternoon of 9 June, the battalion doctor of the 439th Eastern Battalion reported to the FJR 6 command post. He explained the situation of a battlegroup formed from the remains of his battalion, 2nd Battalion/914th Grenadier Regiment and a mixed anti-aircraft unit––they had set themselves up in defensive positions at the mouth of the Vire around a railway bridge.

On the same day, Major von der Heydte received the order to take the battlegroup located at the Vire under his command. Recon troops of 2nd Battalion/FJR 6 established contact between the battlegroup and the main Carentan defense. However, they also soon ran into the enemy, because the Americans had crossed the Vire with their tanks in the combat team’s area and were pushing forward towards Carentan. Major von der Heydte reorganized the battlegroup (it had now been driven back to Carentan) and deployed them as the Battlegroup “Becker” on the right flank of 3rd Battalion/FJR 6 near St.-Andre-de-Bohon.

On the morning of 10 June, the enemy attacked from the east and the southeast, supported by a whole tank battalion. FJR 6’s outer defenses slowly pulled back towards the main line of fighting, and prevented the Americans from pursuing them decisively. Once again artillery and fighter-bomber attacks rained down on the Fallschirmjägers’ defensive line before the ground troops stormed the area. In the north of Carentan, the enemy infantry had attempted an early-morning crossing of the canal in inflatable boats, but they were destroyed in the crossfire.

The Fallschirmjäger were harassed by constant artillery barrages and air attacks, and the Americans finally managed to break through the German lines in the area of 635th Eastern Battalion. In response, 8th Company, FJR 6, led a quick counterattack that managed to push back the enemy successfully, so the German troops could once again take their former positions.

Around 3:00 pm, the enemy artillery barrage suddenly stopped. An American Jeep under the protection of a white flag arrived at the street bridge of St.-Côme-du-Mont facing towards Carentan. Two German prisoners of war, accompanied by some American soldiers, delivered a message from the commander of the 101st Airborne Division, Major General Maxwell Taylor: a message written in German in which General Taylor demanded the Fallschirmjäger’s capitulation with the advice, “Bravery has been well served.” If they resisted, they would face further bombardment.

The letter was given to the commander in the foremost position, Hauptmann Mager of 2nd Battalion/FJR 6. He established radio contact with Major von der Heydte right away in order to save time, because the answer was already clear. Mager wrote a reply on the missive in English: “Would you surrender in the same situation?” and sent the messengers back to General Taylor. At the same time, under orders from Major von der Heydte, 4th Battalion/191st Artillery Regiment fired off a demonstrative bombardment on the southern edge of St.-Côme-du-Mont with their last high-explosive shells.

During these negotiations, the weapons were silent only for a short period. In a hurry, both sides secured their wounded and fallen, moving them away from the front lines. One of the American captives from the first days was a doctor, a captain named Thomas Urban Johnson, who helped the German military doctors treat the wounded. The bandages and medicines taken from the prisoners turned out to be helpful supplements to their own materials, because the reserves of painkillers and bandages were quickly dwindling.

A War of Materiél

The pause in fighting was brought to an abrupt end when the American paratroopers carried out a heavy attack near the Pommenauque farm, north of Carentan. The Americans once again received additional support from their artillery and fighter-bombers. The 10th and 11th Companies of FJR 6 were in the hot seat of bitter defensive fighting and managed to hold the position, but with heavy losses.

Recon troops brought new, worrisome news. During the night of 10/11 June, the enemy had gone around the right flank of the regiment near St. Fromont and had taken up positions there, about nine miles southeast of Carentan, with tank units. Strong Allied forces which had managed to cross the Merderet were also positioned by Amfreville, ten miles northwest of the city. Furthermore, sabotage units were spotted attacking supply vehicles and messengers.

Around 5:45 pm, 10 June, two strong U.S. companies were able, with artillery support, to infiltrate the German defensive lines along the railroad bridge; elements were able to push forward to the Carentan train station. Hauptmann Mager dispatched the 6th Company under Leutnant Brunnklaus to restore the situation in cooperation with the 8th Company. In a pincer movement, they managed to annihilate the Americans.

Around the same time, a patrol of the 5th Company captured three American medical orderlies who apparently had lost contact with their unit. Major von der Heydte sent the men back to their own units with a message written in English. The message stated that, due to their high losses, the Americans could surely use their medical practitioners, and that Major von der Heydte hoped that the American commander would one day know how to return the favor.

Once again, the 635th Eastern Battalion proved the weak link, with serious breaches of its line in many sectors. (At one point, two Eastern battalions took up positions near Carentan, but then quickly defected to the enemy.) Major von der Heydte regrouped his troops and from then on only FJR 6 fought in the important areas—the army units took over securing the flanks. In this way, the front could be held on 10 June against increasingly strong enemy attacks.

But despite the German bravery, the lack of ammunition and other essential provisions was soon readily apparent. The bridges and streets to the German rear were destroyed or impassable, so that barely any provisions could make it through to the fighting troops. While the Americans could land all necessary materials through their “Utah” landing zone, Allied air supremacy prevented effective German resupply. Only one anti-aircraft unit, which appeared in Carentan by accident, not by plan, gave itself to the regiment’s command and proved to be a valuable help.

Eugen Griesser remembers the serious deficit in supplies: “On the evening of 10 June, I only had a little ammunition left for my submachine gun: two full magazines on my belt in a bag and one in the weapon. Because we barely received any ammunition resupplies, I had little more than my 08 [pistol], the bayonet, the spade and a few hand grenades. The war could not be won with this meager arsenal, however, and some of my comrades had it even worse off.”

The Luftwaffe put in a rare appearance over Carentan on the night of 11/12 June. Ju-52 transport planes threw down 13 tons of supplies over the edge of the city, including urgently needed ammunition for rifles and machine guns. Major von der Heydte implored the command of the 1st Fallschirm Army in Nancy for more air supply, but no promises could be made and the drops never materialized.

In a nighttime operation from 10 to 11 July, the Americans attacked the road bridge at St.-Côme-du-Mont but did not move forward from their positions in front of 3rd Battalion/FJR 6. In actions such as these, and in contrast to the German situation, the Americans displayed their material wealth. When the soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division could go no further, they simply pulled back and demanded plentiful air and heavy artillery support. For hours, the men of FJR 6 were subject to punishing bombardments that reduced their positions to rubble and ashes, burying whole troops and platoons.

The Fallschirmjäger did not yield, not even when the ammunition situation worsened. Rifle ammunition had to be collected in order to refill the belts of the machine guns. Every position was held literally down to the last cartridge; only once that was fired would the Fallschirmjäger pull back.

After a three-hour firefight, the enemy eventually succeeded in entrenching themselves in the Pommenauque farm and infiltrating Carentan from the northwest. Again the Americans pushed forward to the train station and occupied part of the building there. In order to close the hole in the defense between the remains of 3rd Battalion/FJR 6 and the 13th Company of the regiment, the 6th Company, moving on their own initiative, threw themselves against the enemy at Pommenauque.

Leutnant Brunnklaus and his men managed to fight through to the road bridge and establish a connection with the remains of the 3rd Battalion located there. Once again, events came down to bitter close-quarters combat between German and American paratroopers. Leutnant Brunnklaus fell in the dense struggle, hit in the back by a pistol bullet.

Meanwhile, the combat reserves of the 2nd Battalion took on the task of recapturing the train station. Cut off from their own forces, the Americans couldn’t hold the building and were slaughtered to a man.

Dietrich Scharrer celebrated his 20th birthday on this day: “11 June was a particularly hot day. We lay in our positions, the sun burned down on us, and our canteens were empty. I collected all the flasks and, during a break in the firing, I ran to find water. After I had filled the canteens with water, I discovered two glass bottles behind an open door. I suspected that spirited cider was in them and took them back for my comrades and me. We figured out that the bottles were too old and that the good cider had turned into vinegar. So for my birthday we toasted with a mixture of water, vinegar, and sugar.”

“Hang In There As Long As Possible”

Around 3:00 pm, Major von der Heydte arrived at positions along the Hiesville–Carentan rail line in order to get an overview of the enemy position. While the 6th Company deployed to the right of the Carentan–St-Côme-du-Mont road had won ground in their operations, the 3rd Battalion, fighting to the left of the road, remained under heavy fire from enemy mortars. Furthermore, parts of the 439th Eastern Battalion and the 3rd Battalion/1058th Grenadier Regiment, which had been sent as reinforcements had been apparently scared off and had advanced no further.

At first individual men, then soon whole groups, fell back because they had run out of ammunition. Across improvised bridges, the Americans could land on two positions along the southern bank; they could now speedily reinforce their ranks. Even tanks were brought into play in large numbers.

In the face of the overwhelming superiority of enemy numbers and weapons, and in response to the completely inadequate provisions situation, especially with regard to ammunition, Major von der Heydte decided to pull his troops back from the northern and western edges of Carentan and then reform on the southwestern perimeter of the city. Holding onto the present positions would have led to the annihilation of his men.

At 5:05 pm, Major von der Heydte reported to the 91st Airborne Division, “All leaders of Jäger companies have fallen or been wounded. Hardest fighting on the city limits of Carentan. The last of the ammunition has been fired; at 1800 hours we will vacate Carentan and fall back to Elevation 30–Pommenauque. This line can only be held if ammunition and provisions arrive.” The tactical leader of the 91st Airborne Division confirmed receipt of the radio message but did not answer it.

The Fallschirmjäger had to disengage from the enemy in leaps and bounds, so as to disguise their maneuver. Eugen Griesser remembers the situation: “In Carentan train station, my unit held the baggage storage rooms. During a break in the firing, the commander [von der Heydte], Hauptmann Mager, Hauptmann Hermann, and another Oberjäger came over to us. ‘What’s the status with you?’ the Major asked. ‘We can still give the Amis hell,’ I said. ‘But when the ammunition’s gone, it will be difficult.’

“The commander knew how serious the situation was, because the other sections had the same to report. ‘Hang in there as long as possible,’ he said. Then he unfolded a map and showed us the prepared positions in the rear. ‘Before the [support] fire is completely stopped, pull your men back to here,’ he said to Hauptmann Mager and Hauptmann Hermann. As he left, he patted me encouragingly on the shoulder and moved on, ducking.”

The Death of Hauptmann Hermann

The battle for Carentan was largely determined by American material superiority. Fighter-bombers swooped on individual targets, and machine-gun nests were wiped out by concentrations of heavy artillery fire before the U.S. infantry advanced. In this manner, and supported by strong tank units, the Americans were able to entrench themselves on the eastern edge of Carentan and push farther forward. The city literally had to be taken by the Americans house by house.

Now the Fallschirmjäger had to pay the price for the way that German tank reserves had been stationed deep in the French hinterland. The 17th SS-Panzer Division “Götz von Berlichingen” was moving towards them from Bordeaux, but it could only move forward under the protection of darkness—during the day, the Allied planes turned the march into a suicide mission. The men of FJR 6 still had only themselves to rely on.

Parts of the 5th Company under the leadership of the beloved Hauptmann Otto Hermann were still trying to push back the enemy through powerful counterattacks. In this way, the Fallschirmjäger came to an open piece of ground, and they suspected that the opposite side was occupied by the enemy. Some young daredevils wanted to cross the field first, but Hauptmann Hermann held them back.

According to an eyewitness: “The Hauptmann called to them: ‘I am in command here, therefore I will go first!’ He rose from under cover and went forward in a crouch. He had barely covered 50 metres when the Americans open fired on him from all sides. Heavily wounded, he fell to the ground. Suddenly the young boys lost the desire to attack. An old Gefreiter pushed the medic forward. ‘You’re the Sani [medic], now it’s your turn!’ But the medic stubbornly refused to leave his position.

“The Gefreiter pulled out his pistol, shot down the medic, and called: ‘Is there another coward who wants to leave the Hauptmann out there to rot?’ We then gave covering fire while he and a few other volunteers recovered the Hauptmann.”

The Fallschirmjäger took the heavily wounded man to the next aid station. Shortly thereafter, the Hauptmann succumbed to his wounds.

“The Lions of Carentan” and the “Kiss-My-Arse Division”

The situation became ever more desperate for the individual battlegroups, because soon the ammunition for the automatic weapons became scarce, and the enemy kept adding reinforcements to the battle. Furthermore, one depot did not have the necessary ammunition on hand, while the personnel of another explained to the men of the WuG Troop that they were not responsible for Carentan. So while the Fallschirmjäger were going against American tanks with empty weapons, a depot administrator refused them the ammunition that could have helped them keep control of Carentan!

On the way to the regimental command post, Major von der Heydte met the chief of staff of the 17th SS-Panzer Division “Götz von Berlichingen,” who had driven ahead of his troops in order to investigate the situation. When Major von der Heydte reported to him, in accordance with protocol, that he had just given the order to evacuate the city, the SS man flew into a rage, because his division had been redeployed specifically with the assignment of securing Carentan and leading a decisive counterattack in the region.

He thrust aside Major von der Heydte’s objections and produced the orders for the subordination of FJR 6 to the 17th SS-Panzer Division, and thus removed the major from his command.

The eventual arrival of a fresh division gave the Fallschirmjäger hope that Carentan could still be held. Their disappointment was that much greater when not a single SS man took up a position within the city itself.

On the evening of 11 June, while his Fallschirmjäger were clearing out of their last positions in Carentan, Major von der Heydte reported to the division’s command post and Brigadeführer Werner Ostendorf. He accused von der Heydte of cowardice, but he was eventually forced to take back his untenable accusations when the commanding general of LXXIV Corps, General Dietrich von Choltitz, joined the conversation (like a Deus ex machina, according to von der Heydte’s memoirs) to express his admiration of the major for the resistance he had maintained for six days in Carentan. [Major von der Heydte’s command of FJR 6 was restored.]

General von Choltitz coined the phrase, “the Lions of Carentan.” Nonetheless, the Fallschirmjäger felt that the Waffen-SS had left them in a lurch. Had the SS reinforced the city, Carentan would not have been vacated on 11 June. The main benefit of the 17th SS-Panzer Division for the paras was they could supply some ammunition and rations.

Gerd Schwetling, an Obergefreiter in the 6th Company at the time, had low opinions of these particular troops: “The 17th SS was one of the new divisions that had been put together in the spring and basically had no combat experience. Maybe that’s what caused their snobbery; they hadn’t had any interactions with Fallschirmjäger yet. Looking back on it, it doesn’t surprise me that a high-ranking SS officer, who had run across my path in the half-darkness, had jumped to attention and saluted me quickly. He probably thought that he had run into a superior officer.”

The new line of defense southwest of Carentan was much shorter than the old line, and therefore it could be occupied by Fallschirmjäger in denser positions. But after six days of ceaseless deployment against a more powerful enemy, the men of FJR 6 were burnt out and completely exhausted. As a precautionary measure, Major von der Heydte pulled them away from the front line so they could catch their breath; he left the rest of the army infantry in their positions overnight.

The Wehrmacht report from 11 June 1944 stated: ‘Under the leadership of Major von der Heydte, 6th Fallschirmjäger Regiment distinguished themselves in heavy battles in the enemy beachhead, and in the destruction of the enemy paratroopers and air landing troops landing in the area.”

Yet, despite the clear appreciation of the performance of FJR 6 since the first day of the Allied landings, there were further attacks on Major von der Heydte. These attacks only stopped after General Kurt Student and General Eugen Meindl, independently of each other, declared that they would have acted in the exact same way in such a hopeless situation. Outvoted by three generals, the 17th SS-Panzer Division (now referred to as the “Kiss-My-Arse Division” by the Fallschirmjäger), supported by 2nd Battalion/FJR 6, fell in on 12 June to storm Carentan.

Von der Heydte’s “Volunteers”

FJR 6, now subordinate to the division, took over securing the right flank, with the assignment to occupy and hold the Carentan train station while the SS division undertook a counterattack from Carentan towards the coast. At first, the Americans seemed impressed by the tank units of the Waffen-SS, and they pulled back, but it turned out they only partially retreated to escape the hail of bombs and rocket fire from the air support they had quickly called in.

Surprised by the intensity of the Allied air attacks and the firepower of the enemy artillery, the Waffen-SS forces quickly came to a standstill and were caught in the enemy’s fire. The SS approached the battle with a “murderous idealism” (as Oberleutnant Martin Pöppel later described in his memoirs), but without prior battlefield reconnaissance and sufficient artillery support, spirit alone was not enough to win the city back from the Americans.

The men of FJR 6, meanwhile, managed to occupy the train station according to their orders, and prepare themselves to defend it; the fighting of the past few days had given them enough knowledge of the area, and the fighter-bomber attacks were nothing new to them. Some Fallschirmjäger couldn’t conceal a certain Schadenfreude [joy at another’s suffering] at the fact that the Waffen-SS, with all their pomposity, had failed miserably in Carentan.

Hurrying in with the regimental combat platoon, Major von der Heydte ordered his officers to round up all scattered and fleeing SS grenadiers and incorporate them into the Fallschirmjäger—some of the grenadiers could only be convinced at gunpoint. Major von der Heydte inspired the bunch of men who had been thrown together; transfer papers to the Luftwaffe were filled out for the SS men, and he accepted volunteers into the Fallschirmjäger troop.

The nearest messenger carried the documents to the corps command post, from where they were sent on to the Reich Air Ministry. Thus FJR 6 had received reinforcements. While the losses suffered in the battle of Carentan were not made up in the least, Major von der Heydte preferred even this small number of new men as replacements, as opposed to the actual big fat zero that he had received as official replacements.

While the 17th SS-Panzer Division, heavily wounded, pulled back to its original jump-off position, FJR 6 pulled back and its men were reunited in their positions having suffered minimal losses. One forward regimental company continued to hold off the American advance. One of the most important roads into Carentan was kept free by firing machine guns along it from covered positions. The American paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division, trying to advance, were forced to stay in place by the concentrated fire.

When the U.S. soldiers, despite a German bombardment and their own heavy losses, finally managed to push forward, the Fallschirmjäger evaded them and fell back into other prepared positions, from which they continued resistance with their remaining mortars. The company finally withdrew on the evening of 12 June to the regiment’s new positions, as now three American divisions with strong tank support attacked the city from three different directions and occupied it.

Brigadeführer Ostendorf now accused Major von der Heydte of not having held his position. But in the face of his own defeat, he was unable to counter the major‘s cool response that FJR 6 simply covered the retreat of 17th SS-Panzer Division and followed their general reduction of the front.

The news now arrived that an attack by the 100th Panzer-Ersatz Division (Tank Replacement Division), about six miles west of Carentan, had not improved the German situation in the region. Accompanied by some officers, the commander was said to have left his troops during the battle, as though fleeing. The situation was tumultuous because some of the troops had surrendered to the enemy, while others dug in their heels and tried to hold out.

Major von der Heydte sent his 3rd Battalion out to stabilize the situation, because if the Americans were to advance successfully in that sector, it would be possible to cut off and surround FJR 6 and the 17th SS-Panzer Division. Because the major recognized the general helplessness of the Waffen-SS, he moved the regiment to prepared positions in the rear, southwest of Carentan. The terrain there was not well suited to tanks, and therefore the next four weeks were mostly determined by infantry actions.

Nevertheless, the enemy artillery was still a great danger and the nonstop Allied fighter-bomber attacks were giving the Fallschirmjäger a tough fight. In the land battles, however, the men of FJR 6 were particularly tough opponents for the Americans. It took the Allies 24 days to wrest 11 miles of land from them between Carentan and Périers, the outer points of the new defensive line, where FJR 6 took up its positions between Raffoville and the River Sèves.

A Letter Home

At this time, the remains of the 1st Battalion, the so-called “Emil Unit,” relocated via Paris and Weissewarte to the air base at Güstrow in Mecklenburg to form a new 1st Battalion. On 17 June Werner Haase, an Obergefreiter in the 14th Company, found time to write a letter to his family:

“You have probably waited for a few lines from me for a while. Today’s the first time it has been possible for me to write to you. I’m sure you know from the radio or newspaper how it’s going here with us. This is the first letter that I can say comes directly from the battlefield. Until now I have always gotten away unscarred, and I hope that I continue to do so.

“Everything’s going okay. I was deployed to the point that was, at first, the weakest point. You’ll have heard on the radio how there was a battle for one city that had to be given up after a few days. Our regiment has shrunken down to only a few because of this city. If you find an old newspaper, you’ll be able to read more about it. I’ll only give away the name of our commander: Major von der Heydte.…

“To a soon and healthy reunion! Greetings, Werner”

The reunion never happened. On 20 June 1944, only three weeks after his 21st birthday, Werner Haase fell victim to an enemy sharpshooter. Because his foxhole could be seen by the opponents, his comrades only managed to get to him after darkness fell; they brought him to the main first aid station where it was discovered that one small, clean shot had gone through his left armpit. The bullet had gone straight into his heart.

Reinforcements

At the beginning of July, the remains of 17th SS-Panzer Division were relieved by the 2nd SS-Panzer Division “Das Reich.” This division had a lot of experience in the field at this point, and worked well with the Fallschirmjäger.

FJR 6 also received replacements at this time, although the 830 new men could not completely make up for the losses they had suffered. In addition, many of the new arrivals needed uniforms and weapons in order to be ready for battle. Major von der Heydte wrote in his memoirs: “About a third of them didn’t even have a steel helmet, over half had ripped footgear, their training and their morale were even worse than it had been with the original regiment.”

Obergefreiter Franz Hüttich had a similar impression: “Among the replacements were many young boys around 17 or 18 years old, who had absolutely no combat experience and had basically been brought into the military directly from the school benches. They were no well-trained Fallschirmjäger, whom one could send into battle without concern. There was no evidence in their behavior of training or jump school. We had to teach the boys everything, and because we were constantly deployed into combat, they had to learn very quickly if they weren’t going to fall in battle.

“Others came from the practice of Heldenklau [“hero-stealing,” the process of recruiting soldiers from other divisions] in the offices and air bases, redeploying them to a new troop. These were men from ground personnel that hadn’t held a weapon in years; they had voluntarily signed up for the Fallschirmjäger troop after hearing the persuasive talks of the recruiters. Some had been threatened with deployment to the Waffen-SS, because the ranks of the fighting troops urgently needed to be filled up.”

The regiment only just managed to equip, clothe and arm the new arrivals. Major von der Heydte reorganized the companies of FJR 6, so that battle-experienced Fallschirmjäger would be standing shoulder to shoulder with the young boys. Nevertheless, the companies were not more than 30–40 men. The Americans were getting bogged down attacking the defensive positions between Périers and St.-Germain-sur-Sèves, which were echeloned in depth.

The newly formed 16th Company, which had been created out of the bicycle platoon and the regimental combat platoon, had counterattacked and cleared up a breakthrough in the main line of resistance by the American infantry on 4 July. Obergefreiter Rudolf Thiel and his group managed to take 15 prisoners during this action. He received an Iron Cross 1st Class for his efforts.

Having completely captured the Contentin peninsula, the Americans now channeled more and more reinforcements into the Carentan sector. The American paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, after suffering heavy losses in the battle against FJR 6, had been relieved from the frontline. Now the Fallschirmjäger faced a new and no less tough enemy, the U.S. 90th Infantry Division.

In the final installment of the story in the next issue, the depleted and badly mauled FJR 6 is withdrawn from the front lines and built up with replacements, 75 percent of whom were mere teenagers with little military training. It proved to be the regiment’s most difficult time. You can find Part I here.

Major von der Heydte had a very interesting career and life.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_August_Freiherr_von_der_Heydte