By David Alan Johnson

“All I knew about Biak was that it was an island a degree south of the equator, one of the Schouten group lying north of Geelvink Bay toward the western end of New Guinea.”

Colonel Harold Riegelman made this admission of ignorance toward the middle of June 1944, shortly after coming ashore on the island. By that time, the U.S. Army’s 41st Division had been fighting its way inland from Biak’s southern landing beaches for nearly three weeks. In the coming weeks and months, Colonel Riegelman would learn more about Biak than he ever could have bargained for.

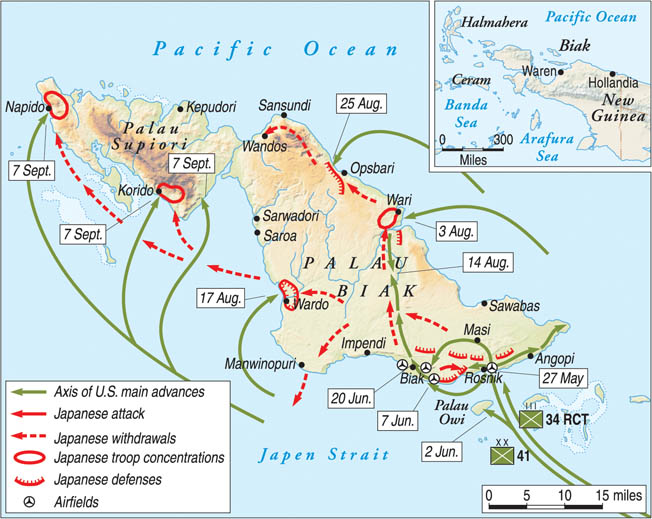

The landings took place on May 27, 1944, near the town of Bosnik. Opposition from the Japanese troops occupying the island is usually described as “light,” something of an understatement. Resistance was so insignificant that some senior officers speculated that the Japanese had evacuated the island. Actually, the defending Japanese troops had been caught off guard by the landings and were not prepared to make any sort of counterattack. They held their fire, reorganized, and waited for the following day to begin their resistance.

Soldiers asked why this God forsaken heap of jungle rot, coral, and caves had to be occupied. Soldiers in every army, in every era, have asked this question, but senior planners had an answer this time. Strategically, Biak had to be taken. The Japanese had built three airfields on the island—at Mokmer, Sorido, and Borokoe. Capturing these air bases would not only deprive the enemy of their use, but would also put American bombers within 800 miles of the Philippine Islands, where American troops were to land in October 1944.

But the high-level planners underestimated Japanese resistance on Biak. Enemy troop strength was thought to be about 4,400, but actually more than 11,400 Japanese were on the island—well over twice as many as estimated. Planners also thought the occupation of Biak would take about a week. They were wrong about that as well.

12,000 Troops Land on May 27

A coral reef just off the landing beaches created a problem that the naval planners knew something about. The reef ruled out using conventional landing craft for the landings. Instead, amphibious LVTs and DUKWs were employed. Both of these were able to cross the reef, land the troops, and return to LSTs offshore for more troops and supplies. Using amphibious vehicles might have been slightly unorthodox, but the LVTs and DUKWs did the job. All 12,000 troops—the 41st Division, along with the 162nd Regiment—as well as artillery and 12 Sherman tanks were put ashore on May 27. The landings went a lot easier than expected. But, as one officer phrased it, “the worst was yet to come.”

The troops began moving toward the airfields the following morning. Patrols from the 162nd Regiment had advanced to about 200 yards of Mokmer airstrip when defending Japanese opened fire with machine guns and mortars. Limestone caves about 1,200 yards north of Mokmer airstrip constituted the key to the defense of Mokmer village. Another line of caves formed natural defenses north of the village, and a third section of caves to the west of the landing beaches, in an area known as the Parai defile, was fortified with pillboxes. These caves gave the Japanese a great advantage, allowing them to hold up the American advance toward the airfields for nearly a month.

The destroyers USS Wilkes and USS Nicholson came as close to shore as their captains thought prudent, firing 5-inch shells into the Japanese positions near Mokmer, but the Japanese relocated to the Parai defile, where they held their ground and opened a withering fire against the advancing 162nd Infantry. The destroyers came under fire from shore batteries, which damaged at least one of the ships.

“Artillery, machine-gun fire, and mortars plastered our troops,” remembered Colonel Riegelman. “The forward battalion was cut off by an invisible, deadly wall of steel and lead.” The advance of the 162nd had been stopped dead.

The Type 95 Tank vs the M4 Sherman

By this time, it had become clear that the airfields would not be taken until the Japanese were driven out of the caves that dominated the landing area. Dense jungle vegetation, the closeness of American troops to the target area, and especially the cover being given by the caves made it impossible for naval gunfire to rout out the enemy. The 162nd Infantry was hemmed in on three sides and under constant fire from concealed Japanese positions. The men would have to be evacuated from their position if they were not to be annihilated, and there was only one way out—the same amphibious landing craft that brought the troops ashore would have to take them off the beaches.

All available amphibious craft were pressed into service. Under cover of artillery, naval gunfire, and air support, the men were taken off the beaches during the afternoon of May 29. By nightfall, the regiment had been evacuated from Parai and landed about 500 yards away to set up a new position. It had been a near disaster, but the evacuation had succeeded.

The Japanese launched a counterattack the next morning with infantry supported by six light tanks, but Sherman medium tanks from the 603rd Tank Company were on hand to face the attack, having moved up from Bosnik to support the infantry. One soldier compared the appearance of the tanks with a scene from a Hollywood film, with the Shermans coming to the rescue of “the surrounded dogfaces” just in the nick of time.

The Japanese Type 95 tanks, equipped with 37mm cannon, could not do much damage to the Shermans, but the 75mm guns of the Shermans punched holes right through the sides of the Japanese tanks. A 37mm shell hit the turret of one of the Shermans, locking its gun in place. The driver backed into a shell hole, which elevated the front end of the tank along with its gun and allowed the gunner to bring his 75mm to bear on a Japanese tank. The Sherman knocked out the Type 95 in spite of the damage to its turret.

Formidable Cave Defenses on Biak

Stopping the Japanese tanks provided a reprieve for the 162nd Infantry. The men were having enough problems with the island itself. Jungle trails slowed forward movement to a snail’s pace, while equatorial heat slowed the men just as effectively, and fresh water was scarce. The men were limited to one canteen of water per day, which everyone soon discovered was ridiculously inadequate.

The caves gave the Japanese a system of natural defenses that was much more effective than anything they could have built themselves. They allowed Japanese troops to pop out into the open, fire on unsuspecting Americans, and disappear again. Mortars and artillery were also brought into the caves, both to protect them and to keep them out of sight. The “cave defense” was brilliantly effective, much to the frustration of the men of the 41st Division. It quickly became evident that taking Biak would be a long and grim business.

The caves were not just holes in the sides of mountains. Some of them were equipped with electric lights, wooden floors, and kitchens. Some were two and three levels deep. A series of tunnels connected the caves and led to hidden exits. The Japanese “laid ambush after ambush,” one soldier remembered.

The 163rd Regiment arrived on June 1 to reinforce the 41st’s drive toward the airfields. Mokmer drome was captured on June 7, but the airfield was still of no use to American aircraft. Japanese troops in nearby caves kept the Army engineers from making the field operational with steady mortar and artillery fire.

Some of the smaller caves were sealed by a sort of skip-bombing technique by Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk fighter-bombers. Closing others was going to be a long, slow process for the infantry.

“My God, it Looks Like a Scene From Hell”

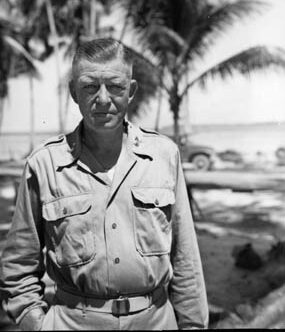

The capture of Biak was progressing too slowly for General Douglas MacArthur, who had expected to have at least one of the airfields operational by this time. He decided to relieve General Horace H. Fuller of task force command. General Fuller was also commander of the 41st Division and was originally to have stayed on. However, he refused to stay since he felt that he had lost the confidence of General MacArthur. Fuller was reassigned outside the Southwest Pacific Area on June 15. The division was taken over by Brig. Gen. Jens A. Doe, who had commanded the 163rd Regiment.

Soldiers went about the business of clearing the caves with grim determination. Some used flamethrowers, crawling within point-blank range of the entrance under the cover of rifle fire and burning out the cave interiors with long streams of fire. Sometimes the flames would hit one of the cave walls and bounce back at the Americans.

division’s original commander, General Horace Fuller, was relieved of duty.

Flamethrowers were unable to reach far enough inside some of the larger caves. Satchel charges, hand grenades, and gasoline were usually employed for these. Gasoline was sometimes poured into one of the openings and then set on fire. After a few minutes, dull thuds and rumblings could be heard coming from the cave’s interior—ammunition supplies were exploding, destroying the cave along with everyone inside it.

The effect of satchel charges was every bit as horrific as that of gasoline. After one cave was blown apart, a private went inside to see what was left. He came out a few minutes later, nauseated and vomiting. “My God, it looks like a scene from hell,” he said. “Pieces of men all over the tunnel floor! Bodies with bellies blown open by concussion! Blood running from the ears, noses, mouths, and eyes of dead Japs! It’s awful!”

In late June the Americans attacked the West Caves, north and west of Mokmer. The infantrymen used gasoline, hand grenades, and explosives to neutralize them one at a time. The deadly work took nearly 10 days and sometimes required the support of Sherman tanks. The caves were finally cleared by the end of the month. Now that they were no longer being harassed by enemy fire, the engineers were able to make Mokmer drome operational. On June 22, the airfield began landing fighters.

Riegelman Studies the Caves

Colonel Riegelman had the chance to take a look around the vicinity of the West Caves and spoke with some of the men who had been engaged in the heavy fighting. He was matter of fact in his evaluation. “I saw the disabled Jap tanks, inspected a nearby mortar platoon, talked to the men, noted their drawn, bearded faces and eyes, red from lack of sleep. They did not complain.”

Riegelman also made a study of the caves on Biak and divided them into four types. Type One consisted of a “cavern in a cliff” from three to five feet in depth, which was used either for a machine-gun emplacement or a storage area for food and ammunition. Type Two was larger, 20 to 30 feet high, facing the sea, with a rear opening from the landward side for access. The cave’s forward opening was “usually improved” by a “concrete machine-gun port” that served to make the already formidable position even more formidable. Type Three was made up of “a series of connected open cavities four to eight feet in height and three to six feet in depth.” Type Four caves were the largest, “more or less circular in shape, up to 50 yards in diameter, 15 to 60 feet deep, with sheer or steeply sloping sides.” The Type Four cave might also be “the entrance to a succession of chambers and interconnecting galleries,” actually a cave network with multiple entrances as much as 100 yards apart. The caves were defensive marvels, but the Americans were becoming experts at improvising methods for neutralizing them.

850 Pounds of TNT

An artilleryman remembered that one cave was “impervious to all calibers we could bring to bear. Its entrance defied demolition.” This was clearly a job for the engineers.

A party of engineers arrived at the cave with what was described as “a quarter-ton trailer” carrying 850 pounds of TNT. A winch was set up, and the TNT was lowered into the cave. “I had no idea what 850 pounds of TNT would do,” an observing officer admitted. “I only knew it was a lot of TNT.”

Nobody else knew what the TNT would do either, but nobody was taking any chances. All troops were ordered back 100 yards from the cave entrance, and nearby Shermans were pulled back to safer ground. Everyone got down on their stomachs, flat on the ground, and waited for the explosion.

When the TNT went off, a cloud of dust and smoke billowed out of the cave, followed by the thud of hundreds of falling rocks. After the smoke cleared, the men and the Shermans were ordered back into position. The men advanced toward the cave’s gaping mouth and stared into the blackness.

“The blackness stared back,” said one observer. The troops sent into the cave were ordered to bayonet every Japanese soldier they could find, whether they were breathing or not.

On June 20, both Borokoe and Sorido airstrips were taken by American troops. The major objectives on Biak—the three airfields—had been captured, but there was still a sizable Japanese force on the island.

About 1,000 Japanese troops occupied the East Caves, situated close to the original landing beaches. They kept up sporadic artillery fire directed at the three air bases. Initially, the fire from these caves had been considered a nuisance. After the West Caves were cleared, the East Caves became the primary objective.

Artillery began firing at the caves shortly after Borokoe and Sorido were safely in American hands. Engineers and infantry from Mokmer moved into the area under the cover of 75mm fire from the Shermans and began clearing the caves using the same methods that had been successful against the West Caves.

Most of the caves had been neutralized by July 5. Their occupants had either been killed or had slipped away into the jungle.

“Score 109 to 1”

Not all Japanese troops took cover in the caves and waited for the enemy to attack. On the night of June 21-22, a counterattack was attempted against the American positions near the West Caves. According to Lt. Gen. Robert Eichelberger, who had been sent to Biak to appraise the situation for General MacArthur, an attack was made by 109 Japanese officers and men against one of the 186th Regiment’s outposts.

“What a racket,” Eichelberger reported. “They came crowding down the moonlit trail in a mass, shouting their banzais.” The 186th’s position was occupied by 12 men who held their fire until the charging enemy was only a few yards away. Machine-gun fire killed many attackers. One Japanese soldier was shot trying to bayonet an American sergeant. Another jumped into a foxhole with one of the Americans and pulled the pin on a hand grenade. The grenade exploded, killing both men. Every one of the attacking Japanese was killed.

“Score 109 to 1,” General Eichelberger said.

Other attacks were made all along the line that night. Each had the same result. Machine-gun fire shredded the Japanese.

“It was mass execution,” one American remembered, “mass suicide of men who wanted to die.” Stories began to circulate about a single squad of Americans killing nearly 200 Japanese. None of them would surrender. They would rather die than give up. One American said, “Usually a sure sign that the Japanese knew that they were licked.”

If the Japanese knew they were beaten, they were not letting it show. The next objective for the American troops, specifically the 163rd Regiment, was the Ibdi Pocket, about 4,000 yards east of Parai. The attack began in mid-June and continued until the end of July. Over 40,000 mortar and artillery shells were fired into Japanese positions during the first two weeks, but the enemy managed to put up stubborn resistance.

By July 10, American patrols reported that the constant shelling had considerably weakened the enemy. The pocket had been methodically blasted away. This was encouraging news for the men of the 163rd as they renewed their attack on July 11. Backed up by artillery, aircraft, and Sherman tanks, infantrymen used flamethrowers and bazookas against the weakened enemy positions.

Progress was slow and costly in human terms. Besides losing more killed and wounded, the Americans were coming down with debilitating illnesses such as typhus and “fevers of unknown origin.”

Using Poison Gas on Japanese Cave Defenders?

Senior officers began looking for a way to end the fighting as quickly as possible. Poison gas was considered and discounted. “We captured a lot of it,” one man said, “just the thing for these caves.”

Colonel Riegelman was asked, “How about it, Chemical Officer? What do you do with those caves?” Riegelman answered, “We got a lot of Jap gas that isn’t being used, sir.” The conversation stopped for a moment. Nobody was sure whether the exchange was supposed to be funny, but it resumed a short while later as if nothing had happened. The joke, if it was a joke, had been dropped.

Sometime after this, the subject of the captured gas came up again. This time, there was no levity. Colonel Riegelman’s commanding officer asked him, “How much Jap gas do you have?”

“Plenty, sir,” the colonel replied. “We have taken great quantities, mostly poison smoke.”

The officer asked Riegelman if the gas could be used against the Japanese and explained that his staff disagreed with his intent to do so if possible.

Riegelman responded, “Sir, in my opinion the staff is right, and I believe you’d be relieved in 24 hours after you used gas. In the end that would cost us more in time and casualties than if we keep on as we are.”

Riegelman did not explain exactly what he meant by “casualties.” He was probably referring to the officers who would face punishment if they elected to use poison gas. He returned to his tent and went to bed. “I never thought I should see the day when I would oppose the use of gas against the Jap, especially his own gas,” he reflected. “Yet I could not think I had been wrong in this.”

“A Terrifying Glimpse Into the Soul of Mankind”

The American forces on Biak kept up their offensive through the month of July, in spite of the heat and the jungle diseases. All organized resistance on Biak ended in mid-July, although mopping-up operations continued until July 25. The island was declared secure on August 20.

Nearly 500 Americans were killed on Biak and more than 2,400 wounded, while another 1,000 were incapacitated by diseases. Japanese casualties were up to 6,100 killed, 450 captured, and an unknown number wounded.

Among the dead was Colonel Naoyuki Kuzume, the Japanese commander. No one is exactly certain what happened to Colonel Kuzume. Some reports claim that he committed ritual suicide after the failed counterattack on June 21-22. Others say that he was killed in action afterward or that he committed suicide toward the end of the campaign.

In his narrative of the Biak campaign, naval historian Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison had nothing but praise for Colonel Kuzume and his defense of the island. “Realizing the hopelessness of his position, this brave and resourceful officer caused his regimental colors to be burned during the night of 21-22 June. Whether he then took his own life or was killed in action is not known, but his death marked the end of a well-directed and stubborn defense.”

Not everyone agreed that the defense of Biak was admirable, no matter how stubborn it might have been. “Biak was a battle that gave a terrifying glimpse into the soul of mankind,” wrote another observer. “For all man’s vaunted civilization and culture, he still retreats into the caves when deadly danger threatens. Under the thin veneer of civilization lurks the caveman—a human animal at bay.”

The Biak operation was a success, which was all that mattered to the military planners. Morison wrote, “MacArthur’s prompt and vigorous invasion of Biak proved to be a serious embarrassment to the enemy on the eve of the Battle of the Philippine Sea. That alone made the operation worthwhile; but, in addition, Biak became an important Allied air base for the subsequent liberation of the Philippines.”

Originally Published January 4, 2017

My father was in on the invasion of Biak. Never talked much about it, other then, one time he said things got pretty rough. He ended up coming down with malaria & had some lifetime aggravations because of it.

Very informative article, Thank You

JHMc

I was born on Biak (1956). I remember a few things: The palm trees, beaches and the wrecks of US landing craft, heavily corroded, but still clearly recognizable. Hail to the US Marines!

My uncle was in the 603rd medium tank company. He simply said, “there is no way to describe what happened on Biak Island “.

My Dad, PVT Hans B. Larsen, 50 cal. Machine gunner on Biak, 41st infantry (if I got that right). He trained in at Ft. Lewis in Puyallup Washington. My son went to the Army here in Springfield Oregon. My Dad

was wounded in both arms, and caught malaria. I am a Vietnam vet, I found agent orange to be my wound. Dad called “Lars”.

Thank you men and women for all your help. My Dad told me of an incident and never spoke any more about Biak. It was night time, he was in his foxhole I’m and heard someone crawling around. He took his 6 inch produce knife, a gift from my grandfather, rose up, put it into his back, and ducked back into his hole. He was wounded in both arms and returned to the states to Camp Cook. Now Vandenberg AFB, in Lompoc California. His as didn’t recover like the docs wanted.

I have all his medals and awards decorations, some original. Others from Medals of America. Com. I am making a shadow box to honor him. I have his basic training battalion picture. Makes me wonder how many men are still here. He died, age 56 in 1977. It was a definite PLEASURE to meet and read about You. I used to live in Long Beach California but moved to Harrisburg Oregon in 1990. I am more and more believing he had PTSD like a lot of you, I too have it, along with a host of agent orange “goodies.” I’m 74 now and I know my time to go to Heaven is nigh. War is no friend to any of us. My prayers are for and with you. And your families as well.

Thank You. A1C Michael O. Larsen AF #19848582. PS…. He did give me his bayonet.

Actually, it was the US Army which captured Biak ( I was a US Marine, and also a veteran of Co. C, 2nd Battalion of the 162nd Infantry Regiment).

I was 100 March 5th. With 476th AAA Btn. Landed Bosnek D+3. from LST, Site contained all types of weapons and vehicles. Alligator next to our Bofors 40mm canon. One tree top level zero attacked in aft– devastating return fire. Never saw daytime attack again, but one bomber (5 bombs) every full moon. warned about D6 of Jap naval & troop ship would arrive about 3 pm–our forces could not arrive until 3 hours later. Some of Us retreated into the hills, destroying their equipment. Japs never arrived. Diverted to Saipan. Good write up in “On to the Mariannas” Served on Owi too. 7 miles away. Saw Bob Hope, Jerry Colonna, Patty Thomas, USO show. Bob Hope joked, ” Betty Grable sends her love. Sorry, that is all she sent. Well, you probably have your hands full anyway.” Brought down the house. The caves at the defile held us up for weeks. Left island Dec 1, 45. Pleasant Hill, TN

That was my unit is 41st infantry division was part of the Oregon army national guard the 162 and 1867 long proud tradition known as the bloody jungle ears because of those battles

Did you know anyone by the name of Lapis

i was born in Biak too, what you said are true. But last time i visited Biak in 2018, all WW 2 wreck almost gone..so sad.

My father fought in the Battle for Biak during WWII as a member of the USArmy 186th. I even have a photo of him in 1944 while he was stationed on the island. Of course, he never talked about any of the bloody battles he participated in from 1942 to 1945 in the

Asia-Pacific campaign.

It is only recently that I have learned more than I ever knew about his 3+ years serving in the USArmy 186th Infantryman. He died in 1988 and I knew very little about his military experience or who he really was for that matter. He clearly suffered from PTSD after the war and struggled to live a happy and satisfying life.

My son lives in Biak and married a local girl. Can anyone share info. On Biak caves. Maybe where a diagram could be located.

My dad was there also, only once did I ever hear him talk about it, when I was young.

My dad (41st Inf. / 162nd Reg) was severely wounded on Biak…developed malaria soon after. He also never spoke of it …only a few stories about Rockhampton Australia fitting out. Every once in awhile, out of nowhere, he would tense up and grit his teeth……

Jack H. McMillin, My father was also in on the invasion of Biak, and also never talked much about it, except to my mother. Things were rough and Dad had nightmares about it after the war. Mom did tell me a few things he told her. It was hellish. Thanks for leaving your reply and I agree the article was informative and glad I learned more about the invasion of Biak. Thank You

I was aroud 10 years old when I lived in Biak. I remember visiting the “Japanese Cave” with my father. I was an gigantic but open cave, you could see the sky through the trees. In my opinion much bigger then the “type 4” cave mentioned in the article. According to hear say the army exterminated the japanese here only by flying the C43 Dakotas above the cave and throwing barrels of gasoline in the cave which were then set on fire.

The Marines were never in Biak. It was the Army 41st Division. My father (Staff Sgt. LaVerne Frisque from Wisconsin) was part of the 476 Battalion that landed there as part of the invasion. I am fortunate to still have him at age 97. He has talked extensively about Biak and getting Japanese River Fever.

My father, Alfred Perkins Rogers, was in Biak during the war, in the 476th Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion, Semi-Mobile. He was best friends with your father… He called him Frisque, and they stayed in touch after the war. My dad is turnings 100 years old on March 5, 2022… He lives independently and is still very active and mentally sharp.

I visited this “Japanese Cave” in 1989. There were old rusty 200-litre barrels at the bottom of the entrance, with many bullet holes in them. I think they had been rolled in by US forces, shot up, and lit on fire. A Japanese shrine was near the entrance. The cave was well lit by the hole in its roof, reportedly caused by a US bomb. I picked up an object in the cave and quickly dropped it after I realized it was a Japanese rib.

My dad was a pilot for B24 bomber. He has a photo of his crew on Biak island. I would love to know how the B24’s were used in Biak.

My dad was ground support for b24’s on biak. He landed after the U.S. secured only 1/3 of the island. We have photos somewhere of my dad standing next to a b24 named something like “Vinegar…” We also have photos with him at the caves. He never talked much about it.

I read yesterday in an old Nat. Geo. that 1,000 B-24s were abandoned on Biak after the war. No one needed them anymore…

Alan. Was your dad in the 85th airdrome squadron?

Hi Linda. My paw paw was in the air corps and talked about Biak once. He was a plane mechanic and was on several flying missions.

My father, Ray Myers, was part of the invasion of Biak. He was with Company D of the 186th Infantry. If anyone knows anyone who served with him, I would very much appreciate it if you could contact me. My father was proud of what they did on Biak, but suffered from PTSD for most of his life because of it.

Hello Bridget:

My father was on Biak also he was a signal Corp officer manning radar stations on Biak. I don’t know if he knew your father but at that time he was with the 6th Army which I believe was with your fathers division. They definitely covered the same ground. Towards the end of his life he told me a number of things I believe he had PTSD also.

Please feel free to contact me if you would like.

Lee

I,am from biak, i have tags name Lee Jhon

My father’s cousin was in the 186th regiment at Biak, where he won a purple heart and a bronze star. He was involved in the 109-1 firefight as a machine gunner. He said the following morning they counted 183 dead Japanese.

My father, Wayne R. Olson, was part of the invasion of Biak Island. He was assigned to Unit Battery B, 205th Field Artillery Battalion and was severely wounded on 13 June 1944. The wound to his right leg shattered his knee, resulting in him spending most of the remainder of the war in a hospital undergoing several surgeries and considerable rehabilitation. As a result, his right leg would never bend again and was several inches shorter than his left. He had to be fitted with a prosthetic shoe to make up the difference. For the rest of his life he was plagued with severe back pain, requiring almost constant medication. He reluctantly had to go on full disability at the age of 50. He rarely complained, always proud of his service to his country and thankful that he came home alive. He passed away in 1974. I still treasure his Purple Heart which will be handed down to his grandson in the near future. Thank you for your well written and informative article.

My dad, Lawrence Berg, was also on Biak, where he spent 9 long months. He was also in the 205th Field Artillery. I’ve never known of anyone else from the same unit! Although he died at 44 years back in 1963, I still have a recording made by a radio station in Portland, Oregon in 1945, while he was in the hospital recovering from wounds received on Mindanao. The purple heart didn’t exactly make up for his disability or short life.

Here’s what he had to say: “The terrain on Biak was entirely in the Japs’ favor. We established a beachhead and were held there for about three weeks. This beachhead was three miles long, and about 400 yards deep, and was surrounded by coral cliffs, 400 to 500 feet high. This coral, you know, was something like a honeycomb, or a sponge. It was completely honeycombed with caves of all sizes. Some of these caves had two or three hundred Japs in them. Some only had two or three. But with all of them, it was just a case of burning them out, or blasting them out. All those terrific shellings make it easier of course, buy clearing the jungle vegetation out of the way, and leveling the surface opposition, but you could stay in one of those caves for a lifetime, and not be affected by the ordinary shell fire.”

There’s a film about the 205th in the National Archives, still on the original 35mm celluloid. Perhaps I’ll decide to order a DVD of this sometime when I have some extra funds. I’ll bet our dads knew each other!

My Father was also in the 41st and fought on that Island. It was where he received his second Purple Heart. He was a Corporal at this time. He was with the 41st from the very beginning through their Occupation Duties. My heart goes out to all who fought with the 41st. Sgt Anthony Cueter. My Father

My great uncle, Anthony Mussari, 41st INF, 116th Combat Engineers died there on 28 June 1944. This was the Army’s victory, not the Marines.

Are you related to the Mussaries from Hazleton,Pa. We had a priest at Mother of Grace ,Father Mussari.

I am from northeast Pennsylvania so that could be and likely is a relative.

My dad was with the 116th Combat Engineers, Company A. I never had a chance to talk to him about his experiences. Survived the war but died in 63 from malaria complications.

My Grandfather is a military historian and has recently handed down a couple of items around this battle. Two Japanese Katanas and a large binder of letters from the man who obtained the Katanas during his time on the island during this battle. The letters are incredible to say the least, they begin from his time before at Saidor in April 1944 and go through until October 31, 1944. At the end of the letters it appears to be military records/notes on the history of the 324th Airdrome Squadron from June 1 1945 through June 30 1945. The last document appears to have the subject of “historical Data for the month of March 1946” to “Commanding Officer, Tachikawa Army Air Base, APO 704”. These documents are incredibly detailed and describe literally every day that he was on this island, from men having to leave due to “breaks” to pilots who wouldnt listen and created more problems than helped.

My dad was there May 1945 until Oct/Nov 1945. They were preparing gliders for the invasion of Japan. After the two bombs and the war ended he rode in an LST all the way to Tokyo for the occupation until Feb or so of 1946. When the war ended they removed the radios from the gliders and used a bull dozer to push the gliders into the jungle.

He said there were three airfields on the island and one was manned by African Americans.

My father was with 593d Engineer Special Brigade, Shore Battalion and participated in invasion of Biak. As a tribute to my father, I am assembling material/writing of his experiences in SWPA. My father never spoke to his children about his experiences and only extraordinarily little to my mother. If anyone has information and/or photos as to the Shore Battalion of 593d ESB, I would very much like to chat!

My Uncle PFC Louis DeCicco was killed in action on June 21st on Biak. I think he may have been the lone soldier killed in the 109-1 banzai attack

My dad, William R. Stow, served with the American Red Cross and was awarded a Purple Heart for wounds received in action on Biak May 29, 1944. He never talked about his experiences, except to tell us that “they” asked him if he could shoot a gun, and when he answered yes, he was “put to work”. If anyone knows of other Red Cross who were involved in this, I’d be interested to know.

My father, Clifton Jones, Jr. was in the Battle of Biak. He was aboard one of the 8 LCT’s. His was LCT 257. There were 10 enlisted and 1 officer. My understanding was that it traveled on a larger boat (an LST) until needed. He didn’t talk much abt his time in the Navy (3 yrs service) but did mention a little abt Biak and what this small group did aboard the LCT. They would carry men and supplies to the beach and retrieve men as well. He would tell us abt. a Japanese plane that they shot down and took the pilot onboard. And mentioned a near miss of two bombs dropping near their boat….one landing on each side. He was a Gunner’s Mate. He was also very young; actually entering at age 17.

My father SSGT Lester E Mounts Sr., was with a little known but important group to the Army Air Force’s, the Engineer Aviation Battalion’s that were just like the Seabee’s and Combat Engineers, but rarely recognized for their part in New Guinea, Biak, and the Philippines. After fighting in Oro Bay, and Seidor NG, the next operation Biak, again had aviation engineers in the assault force, 860th, 863rd, and 864th, his unit, Co A, 860th ENG AVN BN arrived at Biak , 8 June 1944. The passage to Biak, with an entire battalion on four LST’s as a rule, was hot and otherwise uncomfortable, but at least the men and machines stayed together. And the men enjoyed a massacre of Japanese airplanes which attacked their convoy. The landing at Biak proved unusually hard. For almost two weeks the engineers unloaded, dodged shells, built roads, and carried supplies. Finally, they got through to the abandoned Japanese airstrip at Mokmer and began to fill the days, spending the remainder of the time under cover or helping the hard-pressed combat troops. Much behind schedule, the aviation engineers at length carried out the airfield construction required on Biak and much more, Dreadful living conditions, casualties, malaria and typhus plagued the men, but they accomplished their job. They suffered as much or worse when the airfield construction program expanded to Owi Island, three miles from Biak. The 860th left Biak 13 November 1944 arriving at Leyte, PI 19 November 1944 and and then fought at Mindoro PI. Someday perhaps this group of hero’s will be acknowledged for there role in the Pacific Theater.

My grandfather Harold Casino was in company A 860th engineer Avn battalion. Have not found much on his military service and he never talked about it .

If anybody knows who is in the photo of the infantrymen in the ducks please help me figure it out because my grandfather says it was him in the middle but I really want to know. Especially since he died when I was 16 I am very fond of him and he is the reason I am joining the marine Corp

My wife’s great uncle Charles F. Burris died on Biak on July 7th 1944. We think he may have died during the push to secure the Ibde Pocket but don’t know much about the circumstances surrounding his death. I have read through firsthand accounts of the battle looking for any information that might give us a clue as to how he died. Any information that anyone has about Charles F. Burris would be greatly appreciated.

My grandfather was Coxswain Samuel Robert Radford. He served in the United States Navy 1941 – 1945 and was awarded the bronze star for guiding invasion ships into Biak “under attack of Japanese troops only 10 feet away.” He also wore the Asiatic-Pacific theater ribbon with three battle stars and the Philippine campaign ribbon. He passed on just over 10 years ago and never spoke much about it. Now I understand why.

R.I.P. Grandpa, you earned it.

https://library.uta.edu/digitalgallery/img/20038281

My father, Thomas ( Tom ) James Duckworth was on Biak. He was a Technical Sergent. He only spoke of his service one time. We ( my Dad, Mother, my daughter and I had traveled to Pennsylvania to bring my sister back to Cincinnati, Ohio for cancer treatment. My Dad, my daughter, Tami and I were sitting in my sister’s living room just silently watching a local Memorial Day parade on TV. All at once my Dad began to talk about memory from Biak. He never turned to address us, he just started talking.”We had attacked a cave and forced the Japs to retreat further back into the cave. The commanding officer had a soldier, use a bullhorn and order the Japs to strip naked and come out of the cave with their hands raised, palms open and surrender. The Japs refused and continued firing at the American troops. The U.S. commanding officer sent orders to bring several drums of aviation fuel from a ship off the beach to the troops at the cave. Some soldiers were dispatched. to retrieve the fuel and bring it to the cave. The fuel drums were rolled into the cave and shot full of holes so the fuel drained into the cave. The fuel was then ignited with a flame thrower. Dad stopped his talking by concluding; ” I can still hear those guys screaming”. He never spoke another word about his time in the military. Rest In Peace Dad, I live you.