By André Bernole & Glenn Barnett

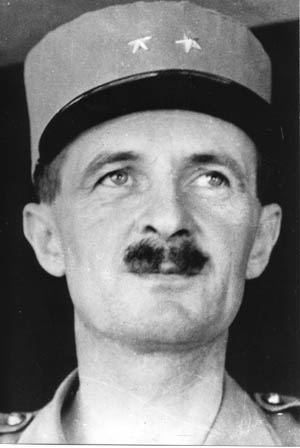

On November 28, 1947, a converted North American B-25 Mitchell medium bomber crashed in the Algerian desert, killing all aboard. Among the dead was French General Philippe François Marie Leclerc de Hauteclocque. Even as his body was being transported back to France the government decided that he should be given a state funeral.

This was unusual. State funerals were reserved for assassinated presidents or great maréchals such as Ferdinand Foch and Joseph Joffre. The convoy bearing the coffins of the crash victims entered Paris by the same route that Leclerc had taken when he liberated the city in 1944. Marching slowly behind the body were some 10,000 veterans of Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division (2e DB), who had spontaneously gathered from throughout France to honor their beloved commander. His wartime boss General Charles de Gaulle wept openly.

Leclerc’s body was placed under the Arc de Triomphe next to the tomb of the Unknown Soldier for eight hours for public viewing. December 8, the day of the funeral, was declared a national day of mourning. The Mass for the Dead was held at a packed Notre Dame Cathedral before his body was laid to rest in Les Invalides near Napoleon and beside those of other heroes of France.

Escaping to England After Dunkirk

Philippe François Marie de Hauteclocque was born on November 22, 1902. The family was one of minor nobility that had served France since the Crusades. It had survived the upheaval of the Revolution to serve in the army of Napoleon and continued to serve in the army in the Great War, during which Philippe’s uncle was killed.

Born into this military tradition Philippe went to Saint Cyr, the French military academy, graduating in 1924. He served briefly with French forces in the occupation of the Ruhr, the industrial heart of Germany, and was later sent to Morocco, where he learned to speak Arabic and Berber, skills that would serve him later. From 1931 to 1937 he was an instructor at Saint Cyr, where he suffered a broken leg when he fell from a horse. He limped for the rest of his life and was always seen with his signature cane.

When war began in September 1939, he was assigned as chief of staff of the 4th Infantry Division (4e DI) and posted along the Belgian border. His division was ordered to hold the banks of the Sambre River, a World War I battle site, against the attacking Germans.

As casualties among the officers mounted, Hauteclocque found himself in command of three battalions of infantry. The Germans soon outflanked their position, and the 4th Infantry was forced to retreat. This process was repeated until by May 25 the 4e DI was pushed back to the city of Lille, 25 miles from Dunkirk. There the French troops made a stand that allowed thousands more French and British soldiers to be evacuated from the beaches.

By the morning of May 28, Lille was cut off and surrounded. The commanding general of the 4e DI prepared to surrender. Hauteclocque did not want to be captured and received permission to try to escape. Threading his way through German lines by night on foot and on stolen bicycles, he was captured twice and twice escaped. He made his way to southern France, where his wife and six children had fled. It was there that he heard the radio appeal of Charles de Gaulle from London and decided to join the cause of the Free French.

Friends were able to obtain a false passport for him. His new identity was as a wine merchant named Leclerc. The pseudonym would become his nom de guerre. It was important for opponents of the collaborationist Vichy French government to use an assumed name as Vichy agents imprisoned and even sent to German concentration camps the families of those who fought them. Hauteclocque would use the name for the rest of his life. He traveled alone through Spain and Portugal, where he was able to take a ship to England.

On July 25, he walked into de Gaulle’s office in Carlton Gardens in London and introduced himself. Knowing his family and hearing his story, de Gaulle promoted him on the spot to the rank of chef d’escadron (major).

Leclerc and the Free French Army in North Africa

De Gaulle wanted to continue the war from France’s colonies and hoped to win them over from Vichy control. On August 6, 1940, he sent a delegation of three men to British Nigeria to represent Free France. Leclerc was one of them. The French colony of Cameroon bordered Nigeria and was targeted first because the French colonists and the natives feared that Vichy would hand Cameroon over to its former colonial master, Germany.

On the night of August 26, Leclerc led a force of 17 men, five officers, and a priest across the swampy border to the town of Douala in Cameroon. Each was armed only with a pistol. To give himself more authority, Leclerc promoted himself to colonel.

Rallying the colonists, Leclerc captured the town without bloodshed and within a week all of Cameroon was in Free French hands. That same week all of French Equatorial Africa, except Gabon, declared for Free France. Leclerc would lead an expedition to capture Gabon in mid-November. In London, de Gaulle gladly confirmed Leclerc’s promotion to colonel.

Delighted with the new African converts, de Gaulle overplayed his hand. He hoped his new popularity would extend to West Africa, but a combined British and Free French fleet was rebuffed at Dakar. De Gaulle consoled himself by consolidating his gains in Equatorial Africa. He also had plans for Leclerc. The two men met again on November 17, 1940.

At the end of the meeting, de Gaulle looked at a large map of Africa showing the middle of the Sahara Desert and said, “Then, there is this [the Fezzan] and then that [Kufra].” Leclerc said later that it was the shortest and most precise order he ever received in his life, “and the one that was executed with the greatest faith.”

De Gaulle removed Leclerc as the governor of Cameroon and sent him to Chad, where he was to organize attacks against Italian Libya. He arrived in Chad in mid-December to command a force of 6,000 native and 460 European troops.

Leclerc inherited a few 75mm cannons and some old underpowered French trucks incapable of traversing hundreds of miles of road, let alone desert terrain. Worse, he would have to haul all of his supplies—food, fuel, guns, and ammunition—from the tiny ports along the Atlantic Ocean through jungle and scrub desert more than 1,000 miles just to reach his starting off points on the Libyan border.

More fuel was consumed in the delivery than was delivered. Still, the British were willing to allocate some of their scant resources and a growing trickle of American goods to support the French in their efforts to discomfort the Italians in Lybia.

About the same time that Leclerc reached Chad, the colony had a surprise visit from a British unit that specialized in hit-and-run tactics. This was a patrol of the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) with Major Pat Clayton in command. The LRDG, operating from bases along the Nile, drove rugged Fords and Chevrolets deep into the desert to strike at remote Italian outposts. The resulting damage caused the Italians to take troops needed for a planned invasion of Egypt to strengthen their desert garrisons.

To be truly effective, the LRDG needed safe areas to refuel and provision. Chad was the perfect choice, and the Free French were willing hosts. On December 21, Leclerc authorized a joint raid on the Italian garrison of Murzuk in the Fezzan Desert of Libya. With 2,000 inhabitants, Murzuk was the most important town in the Libyan desert. Its oasis supported an airfield and an imposing Ottoman fortress atop a rocky outcropping manned by 200 Italians.

Dividing into several groups of two or three trucks each, the combined British-French force began firing on the fortress with machine guns, light Bofors guns, and mortars. Other trucks raided the airport, destroying three Ghibli light planes and a Savoia-Marchetti bomber along with a fuel dump. One British soldier and one Frenchman were killed. The patrol returned to northern Chad on January 19.

The “Oath at Kufra”

Leclerc then turned his attention to the other major town in southern Libya, Kufra. Close to the Egyptian border, the airport at Kufra was an important link between Italy and Italian East Africa. Leclerc decided to take it. He wrote to de Gaulle, “Whatever the difficulties, we will go and we will succeed.” Unlike the joint raid on Murzuk, Kufra would be an all French expedition.

First, however, Leclerc would conduct a raid in strength as a prelude to conquest. Reconnaissance flights were undertaken to obtain photographs and film of the outposts to determine Italian strength and defenses. Next, a caravan of 55 trucks, two armored cars, and two 75mm mountain guns were assembled along with 400 men, 100 of them European and 300 native Chadians. To support them, another 100 trucks and 150 men were marshaled for supply and logistics.

On February 5, 1941, aging Bristol Blenheim bombers operated by the Free French bombed the airfield at Kufra, doing some damage but losing two planes in the desert due to navigational errors. The Italians were alerted to French activity, but Leclerc determined to keep the initiative and press ahead. He would lead the attack himself.

Arriving on the outskirts of Kufra on the night of February 7, 1941, Leclerc used the Arabic he had learned in Morocco to gather intelligence from the local villagers. Then, under the cover of darkness, he led a group of 30 men in six trucks to the airport where he was able to destroy two airplanes in their hangars.

His squad returned to a rendezvous point and moved to the south before dawn to hide in the desert from Italian patrol planes. He returned to Chad with one dead and four wounded.

Meanwhile, the British in Egypt had repelled the Italian attack and were now pushing the Italians back deep into Libya. It was the strategy of de Gaulle and Leclerc to push up from the south to join the British on the coast. It seemed to be the right time to seize Kufra.

On February 17, a Free French truck column led by Leclerc headed north toward the distant town. After the battle, Leclerc would boast to an American correspondent that one of his drivers was a former New York cab driver. “Nothing could stop him,” bragged the general.

The next day they arrived and immediately came under machine-gun fire from Sahariana (Libyan natives fighting for Italy). The trucks had raised so much dust that the French could not fire back until they had cleaned their weapons.

Leclerc then ordered half his men to keep firing while the other half flanked the Sahariana defensive position. They were successful in dislodging the enemy and closed on the fort until nightfall and then dispersed and hid to await the dawn. The next morning, the Italians sent seven Savoia-Marchetti bombers against the French, but finding no concentration of forces they did no damage. At least one of the bombers was hit by small-arms fire and left the area trailing smoke. This was followed by an attack by Saharianas in 13 trucks, but they were chased into the desert away from the fighting.

The French then began to bombard the fort with mortars and their two 75mm mountain guns. The shells from these guns made neat holes in the mud walls of the fort and exploded inside. The Italians had little hope of reinforcement because the entire Italian 10th Army was in full flight from the British on the coast. By March 1, the garrison had had enough. The aging Italian commander, Captain Colonna, who had won the Croix de Guerre in World War I, sent out negotiators. Leclerc dismissed them outright and then jumped on the running board of their car and told the driver to return to the fort.

Inside the fort, Leclerc and two of his lieutenants confronted Colonna and demanded his surrender. By that afternoon Kufra was in French hands. Over 300 Italians and Libyans surrendered to 30 Frenchmen. There were so few French to guard the surrendered Italians that even the priest, Père Bronner, took a turn at sentry duty.

Raising the French flag emblazoned with the Cross of Lorraine, the victors celebrated Free France’s first victory of the war. On March 1, 1941, Leclerc asked his men to swear an oath not to put down their weapons until the French Tricolor flew again over the Strasbourg cathedral in German-occupied Alsace. The “Oath at Kufra” would become a part of Leclerc’s legacy and fighting words for the French.

Garrison duty was not for Leclerc, and with de Gaulle’s blessing Kufra was turned over to the LRDG with the caveat that the Free French flag be flown over the fortress at all times. Much of the fort’s provisions were carried away, and the French in the forward positions in Chad would feast on macaroni, antipasto, and anchovies for weeks. For his actions at Kufra, the British awarded Leclerc the Distinguished Service Order (DSO).

The Fezzan Raids

The Axis was not ready to give up Libya. By March 31, newly arrived German General Erwin Rommel and his Afrika Korps were prepared to strike. In April the British were pushed back to the Egyptian frontier. Only the vital port city of Tobruk held out. Further, Germany invaded Greece, stretching British resources to the limit.

Leclerc incessantly asked for new trucks, supplies, and equipment from the British, but they were now in so much trouble that he had to give up his aging Blenheim bombers to support their sagging fortunes. Advancing northward toward the Mediterranean coast was now out of the question. On May 1, de Gaulle himself flew out to review the troops and confer with Leclerc.

The strategic situation changed in June when the Germans invaded Russia. The British began a buildup in Egypt to support an offensive against Rommel. As part of the buildup, Leclerc began to receive a trickle of new equipment including four Bofors antiaircraft guns, six U.S.-made 75mm guns, 10 armored cars, and 400 trucks. Still, trucks and gasoline were in such short supply that fuel was carried to Kufra by camel, sometimes in caravans of over 100 animals.

British supplies began replacing French provisions. These included tins of suspicious looking bully beef and rum. Wine had run out in Free French Africa, and rum took its place.

Around this time de Gaulle promoted Leclerc to général de brigade (brigadier general), but the proper insignia would not be available for several months. Leclerc turned his attention back to the oasis at Murzuk. While awaiting reinforcements, he planned his next move.

By November 27, the British had relieved Tobruk and pursued Rommel across the northern Libyan desert. By December, the United States had entered the war. Leclerc pushed his forward base to the southern Libyan oasis of Uigh el-Kebir. He was preparing for continued British success and was ready to join them in Tripoli, but Rommel had other ideas.

Reinforced from Europe with new men and equipment, Rommel lashed out at the British and pushed them back into Egypt. On January 21, 1942, a lone German Heinkel He-111 bomber flying 1,600 miles from an improvised base in southern Libya bombed Leclerc’s main airfield at Fort Lamy (N’Djamena) in Chad. Nearly half of his precious fuel was destroyed, and 10 planes were damaged.

After nine months of inactivity following the Kufra operation, Leclerc decided the time had come for action. Instead of trying to capture Italian territory, which Rommel might easily win back, this would be a hit-and-run attack. The targets were to be a dozen Italian outposts in southwestern Libya. There were 150 vehicles, 500 men, and 10 aircraft to carry out raids in a territory as large as France itself. Leclerc divided his forces into several squadrons to accomplish this mission.

The raiders started out from Zouar on February 7. It took six days to reach the forward base at Uigh-el-Kebir. The attacks were timed to begin on February 28. The Fezzan raids lasted for 15 days. In that time, four Italian forts were destroyed, 50 prisoners taken, fuel and ammunition dumps and three aircraft destroyed at the cost of eight French killed and 15 wounded.

Pressed white Italian stars used as insignia were also captured. Leclerc now donned two of these on his kepi to denote his rank of general until proper French stars could be obtained. His new American liaison officer, Colonel Cunningham, wrote, “[Leclerc is] a remarkable soldier, young, energetic and absolutely adored by his officers and men.”

Operation Fezzan-2: Leclerc Reaches the Sea

The British, meanwhile, were on the receiving end of another German offensive. They were thrown back from the Gazala Line to El Alamein. An orderly retreat was in part due to the stubborn stand of a brigade of French Foreign Legion troops (the 13e DBLE) at Bir Hakeim under the command of General Marie-Pierre Koenig.

Leclerc would have to await events before advancing to the coast. Again, he and his bored men hunkered down to wait out the scorching heat of a second summer in the middle of nowhere. Leclerc arranged rotating holidays for his men in South Africa.

Meanwhile, both sides prepared for the inevitable conflict. Italian and German reconnaissance flights were stepped up, forcing the French to operate at night. The ruined Italian forts were reoccupied with fresh troops. The French continued to receive and stockpile supplies and weapons in advanced areas.

De Gaulle, furious at being left out of planning for the Allied invasion of North Africa, nevertheless told Leclerc that when he reached the coast at Tripoli he was to place himself under British command. The two men conferred at Fort Lamy and agreed that the French thrust to the Libyan coast would include 3,000 troops. If upon the invasion Vichy sided with Germany, Leclerc would invade and occupy the remaining Vichy colonies in Africa.

On November 8, Leclerc learned of Operation Torch, the Anglo-American landings in North Africa. On the 12th, de Gaulle ordered him to begin his conquest of southern Libya in operation Fezzan 2. By mid-December, Leclerc’s small army of three columns had reached its advance bases and moved into Italian territory. He stayed in constant contact with his forces by flying across the vast desert to meet with his commanders wherever they were.

The Germans and Italians sent up fighter planes to strafe the French, who had become masters of camouflage, and French progress was rapid. By mid-January 1943, the German grip on North Africa was slipping. The British victory at El Alamein the previous October had seized the initiative, and all of southern Libya was in French hands. By January 26, French troops entered Tripoli on the Mediterranean coast. It was the first time many of Leclerc’s men had seen the sea in over two years.

When Leclerc arrived he was summoned to meet with General Bernard Montgomery, commander of the British Eighth Army. Leclerc showed up in his tattered and thin uniform, covered in Libyan dust and mud. The two men hit it off at once, and the British saw to Leclerc’s resupply needs, providing new trucks, uniforms, guns, and, most prized of all, new boots to replace torn and split shoes or rubber tire sandals. Montgomery personally offered Leclerc a battle-dress uniform, some shirts, and a pair of battle shoes.

Force L and the Battle For Tunisia

In the battle for Tunisia, Leclerc was assigned to fight on the left or inland flank of the Eighth Army. His command was reinforced with Greek and British troops. For the battle it was known as Force L.

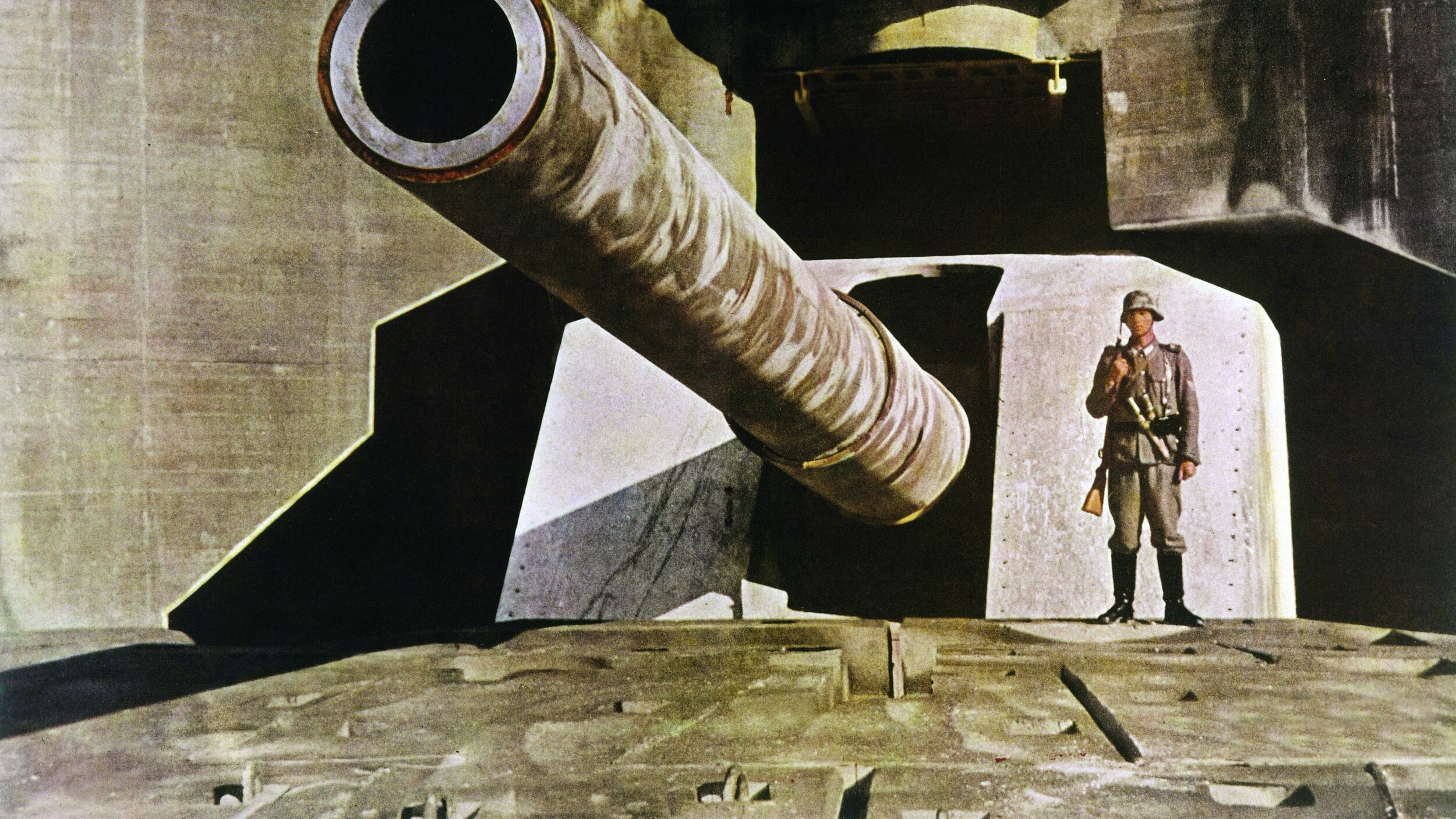

Rommel had hidden his men behind the Mareth Line, a French-built line of bunkers and trenches meant originally to fend off the Italians in the 1930s. Force L was assigned to guard some mountain passes known as Ksar Rhilane to prevent the Germans from flanking the British positions.

As the battle formed up, Rommel sent tanks into Leclerc’s crucible of 600 well-hidden antitank guns and 400 tanks. They were rebuffed with great loss. Rommel then wanted to pivot north, but Hitler would not hear of it and recalled Rommel to Berlin.

The new German commander, General Jurgen von Arnim, also wanted to flank the British position. For that he had to engage Force L again. Montgomery and Leclerc knew of his plans thanks to intelligence and prepared accordingly.

Montgomery, fearing the worst, ordered Leclerc to pull back 50 miles to safety. Leclerc was already dug in and refused to leave his position. He asked only for British air support. Montgomery agreed. The British general did not have faith in Leclerc and lamented to a colleague, “Poor Leclerc! He sure was a nice chap. Now, it’s over, we won’t see him again.”

However, Leclerc knew his business. Three times he lured the Germans into his hidden guns and repulsed them with great loss. When they at last retreated, Leclerc sent a message to Montgomery that he had destroyed 60 enemy vehicles and 10 guns “and they never penetrated our lines.” The British general was surprised and thrilled. “Well done!” he replied.

The failed effort was the last German offensive in Africa. The Battle of Tunisia wound down as the Allies approached the last German-occupied city of Tunis. When the Germans evacuated the continent, some 250,000 Axis prisoners were taken, a greater haul than at Stalingrad.

Force L Becomes the 2nd Free French Division

A great victory parade was planned, but in another insult to de Gaulle, the French were to be represented by a former Vichy force, the Armée d’Afrique. Leclerc was furious. On the day of the event, he sent his troops through side streets to join at the rear of the parade, where they formed up and marched in defiance of Anglo-American wishes. He was wildly cheered by the French population and soldiers of the Eighth Army.

Pleased with his favorite general, de Gaulle promoted Leclerc to three-star general. Force L became the nucleus of the 2nd Free French Division (2e DB), which he would lead with distinction across Europe. Its ranks swelled with deserters from the Armée d’Afrique who wanted to join the man of action.

Leclerc would be the Allied commander who liberated Paris and later fulfilled the “Oath of Kufra” by raising the Tricolor over the cathedral of Strasbourg. He also represented France on the deck of the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay as the Allies received the surrender of Japan. He had earned his place in the pantheon of French heroes.

Why wasn’t he leading French troops on the beaches of Normandy on June 6?

He didn’t join the battle of southern France until July when the Germans were in full retreat.

Because of the absolute desire for secrecy, the Free French weren’t included in the “OVERLORD” plans, due to fears of leak or collaborators in the French ranks. Remember, there were a LOT of Frenchmen fighting the Axis that had family members still under Gestapo control. Also, it was understood that losses could be possibly catastrophic, even Gen Eisenhower had an alternate speech prepared in case of failure of the landing at Normandy. The invasion of southern France was also planned & that was looked upon as being more fortuitous for the Free French chances, since their numbers would be more “diluted” in the forces involved in the south.

Leclerc and 2nd DB landed on Utah beach on 8/1/1944

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xZ8LWe7a0HI

This part of WW 2 I’d never knew of. Thank you for this article.