By Michael J. Bell

The name Leonard Jay Thom may not mean anything to a great many people today, and that is unfortunate. But there are some who still remember. They recall the big, blond-haired man with such a zest for life. They will never forget the gentle giant who, in the short time he graced the world with his presence, touched the lives of so many.

To the historian, Leonard Thom is remembered as the Executive Officer aboard PT-109, the boat that launched the legend of John Fitzgerald Kennedy. He was a key player in the drama that followed that boat’s sinking in August 1943. Like so many others who came into JFK’s orbit, Lenny Thom has become but a footnote in the history books. He deserves so much more. Even if he had never met Jack Kennedy, Lenny’s life would still be worth remembering. He was a true American hero, friend, husband, brother, and father whose life ended far too soon.

Volunteering For War

Leonard Thom was born on September 8, 1917, in Sandusky, Ohio, the oldest of eight children. In high school, the husky Lenny played football, lettering in a sport that showcased his natural talents and ever-growing size.

After high school, he attended Heidelberg College in Tiffin, Ohio, but his experiences there lasted only one year; the duration of his college years were spent at Ohio State. There he played football and was an all-star tackle and guard and was Phi Beta Kappa. Football, however, remained his calling.

For a brief stint, Thom also played semi-pro football for the Columbus Bulls. The Chicago Bears were also interested in Lenny’s talent at one point, offering him $1,000 to sign and $500 a game. Lenny had other things on his mind, though, and passed up this chance.

While at Ohio State, Lenny met a young woman on a blind date to whom he lost his heart. Catherine Holway, or Kate, as she was and is known to her friends, hailed from Youngstown and was attending St. Mary’s of the Springs, an all-girls college in Columbus. She remembers this big, striking blond man walking into the room of the house where a postgame party was being held. They soon began seeing a lot of each other, and when Lenny went off to join the Navy, Kate wore his Phi Delta Theta fraternity pin.

As the war clouds darkened, Thom, like many other young men, volunteered to serve his country in uniform. At that time the U.S. Navy had instituted a program called “V-7,” in which college graduates, or those close to graduation, could join as apprentice seamen. After a month of training as apprentice seamen, they were then appointed midshipmen. As midshipmen they received an addition three months of officer training and then were commissioned as ensigns, following which they were sent either directly to the Fleet or to one of the numerous special advanced schools for their final training.

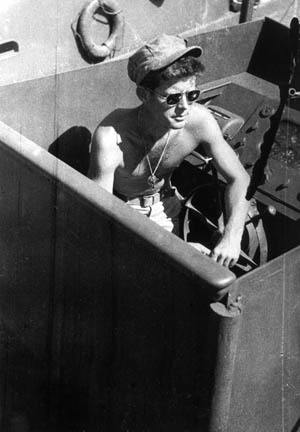

Thom went through the V-7 program at Notre Dame and met a fellow trainee named Joe Atkinson. Since men like Thom and Atkinson did not have the benefit of a Naval Academy education, they went through the accelerated course to become officers in the naval reserve. Atkinson remembered Lenny as a jolly fellow and said in an interview that he loved Lenny like a brother. It was at the MTBSTC (Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron Training Center) at Melville, Rhode Island, that Thom met a sickly looking young naval lieutenant from Boston named Jack Kennedy. The two men became fast friends, and their lives would be intertwined for the next three years.

The Memorable Leonard Thom

In March 1943, newly commissioned Ensign Leonard J. Thom, USNR, was sent to the South Pacific Theater and the Solomon Islands. Thom drew an assignment as Executive Officer (XO) of PT-109, serving under Lieutenant Bryant Larson. After Larson moved on, Thom was pleased to learn that the boat’s new commander would be his old friend, Jack Kennedy. The relationship and trust that these two men had with one another would serve them well over the next few months.

Lenny Thom was not a man people forgot. He made quite an impression. In the book The Search for JFK by Clay and Joan Blair, Charles “Bucky” Harris, a crewmember aboard the 109, said of Thom, “He could rule anybody. You would just look at him and do what he told you. He was an awfully nice man.” Many of his fellow offices recall with great fondness the big man who looked like a figure out of Nordic mythology, especially with the blond goatee that he grew.

Lieutenant Al Cluster recalled his arrival in the Solomons and a discussion he got into about FDR. As a Republican, Cluster was complaining about how President Roosevelt always seemed to appoint his rich cronies to high government jobs such as an ambassador to some place or another. Lenny interrupted and mentioned to Cluster that the young fellow who sat a few feet away was Kennedy. Cluster was not impressed. Thom then explained that it was John Kennedy, the son of Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy. “Right from the start,” Cluster said, “Lenny was helping me out, and kept me from embarrassing myself.”

Cluster also remembered a time when Lenny tried to step in and calm another man down who had been drinking. The sailor shoved Lenny and sent him reeling. The next morning, when told what he had done, the man had tears in his eyes. He could not believe he had shoved Lenny.

In the Solomons, mail would not arrive one letter at a time. It got backed up, and many of the men would receive a number of letters at once. Back in the States, Kate Holway wrote to Lenny nearly every day, so he would get a packet of 30 or so letters at one time. He would lovingly open one each day. (When the ordeal of the sinking of the 109 was over, Lenny told Cluster that the thing he missed most was not being able to open his letters from Kate.)

Life in the Pacific, while often boring between missions, could also be quite interesting. Johnny Iles, who lived in the same quarters with Lenny, Jack Kennedy, and Gene Foncannon, remembered a house guest they had had in their place. He was a young native boy named Lami, who told the officers that he was a cannibal. Johnny remembers Lami eyeing the big beefy forearms of Lenny Thom. Fortunately for Lenny, the New Zealand authorities were notified and soon came to take the young man away. It was not just the Japanese who posed a threat to the PT boats!

Surviving a Destroyer Attack

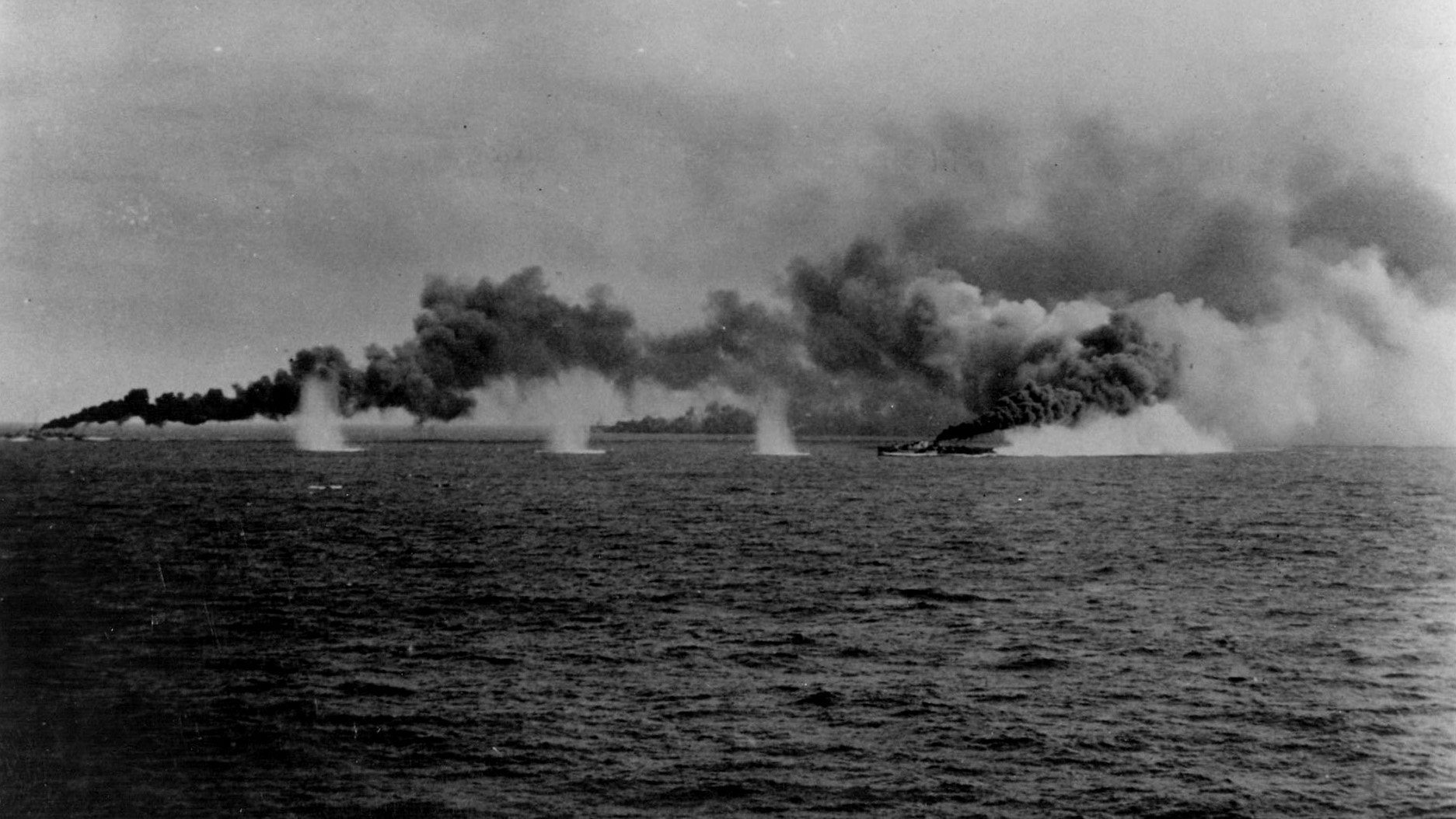

On the night of August 2, 1943, PT-109 was on night patrol in an area of the Solomons known as Blackett Strait. Idling on one engine to keep its phosphorescent wake to a minimum (Japanese float planes frequently found that the wake helped make the PT boats a great target), the 109 was suddenly struck by the destroyer Amagiri.

Historians have claimed in recent works that the crew was relaxing and some were even asleep and that this was why the 109 did not see the ship until it was too late. Lenny told Kate later that is was ridiculous for anyone to hint that the crew of the 109 was not alert. “We were on patrol!” he said. The darkness of the Pacific nights and the confusion among the other boats both point to the fact that the 109 was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. The destroyer sheared off a large section of the 109, causing an explosion seen by Dick Keresey on the 105, some five miles distant. Two of the crew, Harold Marney and Andrew Kirksey, were killed. Lenny helped round up the others and bring them back to the hull of the 109.

Gerard Zinser, the last surviving member of the 109 that night, said in an interview that Lenny was a “great help in getting the men back to the boat.” They clung to the shattered hull of the 109 until daybreak. When it was clear that the remains of the ship would not last much longer, the men swam for an island known as Plum Pudding. It was farther away but smaller than others and less likely to hold enemy troops.

Repeatedly, Jack Kennedy swam out into open waters in a vain search for American ships. While he was gone, Lenny was the man in charge. As the days passed and the men seemed to grow more resigned to their fate, it was Lenny Thom who did not allow them to give up hope. He mustered all that he had within him to keep their minds off the seemingly hopeless situation they were in. Many of the crew, when interviewed years later, said that it was Lenny who served as their rock.

In the Blairs’ book, “Bucky” Harris said, “When Kennedy left, Thom organized us. He used to tell us stories about the farm and the college days … and the things he was going to do. He was Great! He kept everybody’s spirits up. He had no fear, not a worry in the world.” Zinser remembered Thom in much the same light. He said that Lenny was a very good person and a fine officer and that he really helped keep a flicker of hope alive.

“White Star, White Star”

After the men had moved to another island, Kennedy and Ensign Barney Ross (Ross had come along for the ride the night the 109 had gone out) continued to try to flag down U.S. ships. On the fifth day, while Kennedy and Ross were gone, natives discovered the rest of the crew. The natives seemed hesitant about approaching the bedraggled men. It was not until big Lenny Thom stepped forward that the tension eased. He repeated the phrase “white star, white star” over and over again. The natives knew that “white star” referred to the insignia on U.S. planes and that these were Americans. The natives gave the crew some C rations and water. Lenny then convinced them to take him back to their contact so he could get in touch with the base at Rendova. Lenny got into their canoe, but the canoe promptly swamped.

Lenny then used a pencil stub and wrote on the back of an invoice a note that the natives could take with them to Rendova. The note read as follows:

To: Commanding Officer-Oak o

From: Crew P.T. 109 (Oak 14)

Subject: Rescue of 11 (eleven) men lost since Sunday, August 1 in enemy action.

Native knows our position and will bring P.T. Boat back to small islands of Ferguson Passage off Nuru Is.

A small boat (outboard or oars) is needed to take men off as some are seriously burned. Signal at night three dashes (—–) Pasword—Roger—Answer—Wilco. If attempted at day time—advise air coverage or a PBY could set down. Please work out a suitable plan and act immediately on native boys to any extent.

L.J. Thom

Ens. U.S.N.R.

Exec. 109

It was this note, along with the more famous coconut shell on which Kennedy carved a message, that eventually made it to an Australian coastwatcher’s outpost and later the PT base at Rendova. Thom’s note served as confirmation of Kennedy’s coconut shell, which––at first glance––was thought to be an enemy trick.

At the home base on Rendova, some wanted to go out to look for the 109 but were denied permission to do so. It was felt that daylight sorties were not safe, as the Allies had not yet gained air superiority. There also seemed to be a general feeling that nobody could have survived the explosion that many had seen on the night of August 2.

Back in the States, Kate Holway had not heard from Lenny in over a week. The first indication she had that something had been amiss was when she read that Lenny had been rescued; she had not even known that he was missing. Kate later received a wire from Lenny telling her that all was OK and not to worry.

Lenny was awarded the Purple Heart for injuries he sustained and the Navy and Marine Corps medal for his efforts to save the crew. The war and that experience were having an effect. In a letter he wrote to the Ohio State Development Office following the 109 sinking, he remarked that “this too is an education and an experience that one will never forget. But one will be enough. Peace must be lasting and complete this time”—a sentiment shared by many who had gone off to war and had seen their friends and comrades perish.

PT-587 “Thomcat”

When the men of the 109 were rescued and returned to base, it was assumed that they would be going home. This was not to be. A few of the PT boats were turned into gunboats. Lenny was given command of Gunboat 60, Nice. Al Webb was the XO aboard the Nice, and he remembered Lenny Thom being a solid skipper.

Later, Thom was given command of PT-587, which was dubbed the “Thomcat” by its crew, a few who had served with him aboard the 109.

When Lenny did manage to get back home, he married his sweetheart Kate on June 1, 1944, in Youngstown, Ohio. Lenny was assigned to the PT training center at Melville, and the Thoms set up house in Newport. On Labor Day weekend of 1944, the Thoms went to Hyannis Port to visit with Jack and some of the guys, including Barney Ross. There is a picture of all of them on the porch of the main house. Lenny Thom is standing off to the left, while Kate sits in a chair between Jack and Ross. They all seem so happy and carefree. The war had taken its toll, but the future looked bright.

While the Thoms were stationed at Melville, Lenny was able to indulge in his other passion, football. The PT boat men put together a team that played others from throughout the Northeast, including Harvard. Shortly thereafter, the Thoms found themselves moving again, this time to New York. After that stint, Lenny was sent to Florida in preparation for being shipped back to the Pacific to take part in the invasion of Japan. Since the invasion did not come to pass, Lenny was soon on his way home for good, arriving in January 1946.

When Lenny was finally mustered out in the winter of 1946, there was much to be excited about. Kate had recently given birth to a boy, named Leonard Jr., and before long another child would be on the way.

Leonard Thom After the War

Like so many others who had served in the war, Lenny Thom took advantage of the GI Bill to further educate himself. He began a master’s program at Ohio State and worked at Galbreaths Insurance in Columbus, making the commute between Youngstown and Columbus every week. For a time, they lived with Kate’s parents, but the Thoms had soon purchased their first home in the fall of 1946. A letter from Lenny to his mother around this time speaks of the house being redecorated and of Kate finding work as a nurse.

On his way back to Youngstown late on the afternoon of October 4, 1946, Lenny took a route he had never taken before. Near the town of Deerfield, he crossed a set of railroad tracks. He never saw the train. Lenny was the only one of the three people in the car who was conscious when help arrived. “Forget me, help the other fellows,” he pleaded with the rescue workers.

He was rushed to the hospital in Ravenna where he died the next day. After all he had been through, especially the dangerous experiences in the Pacific, it was bitterly ironic that he would pass away in this manner. His friends arrived from all across the country to pay their last respects to their comrade. Kennedy, Atkinson, Webb—they all came to say good-bye.

Lenny was laid to rest in Calvary Cemetery in Youngstown. Kate Thom was overwhelmed by the outpouring of friendship and support she received. She eventually remarried and had seven children with her second husband, Dr. Hilary Kelley. Her two children by Lenny were adopted by Dr. Kelley. Leonard Thom Kelley is now a lawyer in Anchorage, Alaska. Christine passed away in 2000 in Greensburg, Pennsylvania. Kate and her husband live quietly in Greensburg, as well.

Lenny Thom’s family has kept his spirit alive all these years by never forgetting. Family scrapbooks are full of treasured memories. The pages and pages of photographs and clippings show a young man enjoying all that life had to offer. There are testimonies to his courage under fire and the respect and affection countless others had for him. There is an outpouring of grief and utter despair following his untimely death. Lenny Thom touched the lives of a great many people and continues to do so even today.

And in a day and age where historians often seem to take a perverse pleasure in debunking heroes, it is comforting to know that there are still a few genuine heroes for people to look to as role models. Leonard Jay Thom was one such man.

Some of us will never forget….

Thanks for your note — just enjoyed reading the article – and movie a while back. I had no knowledge of Thom until now so very good to learn more about him & other heroes!

My father was a marine in ww2 – Guam , then Iwo Jima, but didn’t have to go on the Iwo island because they had sufficient soldiers already. He deceased now but loved to watch the war films w him. Including Iwo film by director Clint Eastwood.

I am a native of Youngstown, Ohio born in 1951. When in highschool I read the story of JFK and PT 109, and the Ensign Thom, but never made the Youngstown connection until sometime in the 1980’s.

I did some research and found that Mr. Thom is buried near my mom and dad in Calvary Cemetery on Youngstown’s west side. I have visited his grave several times. I always have a feeling of awe, thanksgiving, and respect when I visit.

Andy Brincko

Thanks for your note , enjoyed the article

What a hero he was.