By Dominique Françoise

At the beginning of 1945, Nazi Germany was on the ropes. Being pounded by the Allies from both east and west, it was believed that Hitler’s Third Reich was near collapse. With her cities bombed into rubble, her armies decimated, her economy shattered, and her civilian population on the verge of starvation, Germany was a hollow shell of her once mighty self. A new operation, codenamed Plunder, was seen by its planners, principally British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, as the final knockout blow.

If the British and American armies could cross the Rhine in the north—at or above the cities of the Ruhr industrial complex—then the Western Allies would have a straight shot toward Berlin and bring the war to a speedy conclusion.

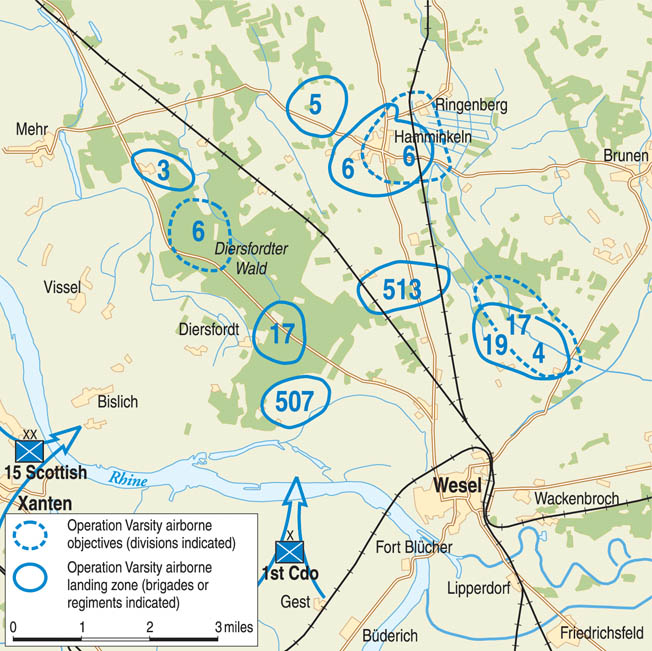

Montgomery’s 21st Army Group’s Operation Plunder was designed as a joint British-American push across the lower Rhine and into Germany’s heartland. The ground assault would be conducted by Lt. Gen. Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army and Lt. Gen. William H. Simpson’s U.S. Ninth Army. A key component within Plunder was Operation Varsity, a huge parachute and glider assault that would employ both U.S. and British airborne divisions under the aegis of XVIII Airborne Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Matthew Ridgway.

For months in late 1944, the Allies prepared for this final push, gathering equipment and supplies, improving techniques for crossing rivers, and selecting certain armies, corps, divisions, and regiments to take part in the effort.

These planned airborne and glider forces consisted of the British 6th Airborne and the U.S. 13th and 17th Airborne Divisions (with glider and parachute artillery elements). Those airborne forces would be Colonel Edson D. Raff’s 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), Colonel James W. Coutts’ 513th Parachute Infantry Regiment, and Colonel James R. Pierce’s 194th Glider Infantry Regiment. The 13th Airborne Division was ultimately dropped from the operation due to limited airlift capability and would never see combat as a division, although some of its personnel were used as replacements.

After the summer battles in Normandy, Raff’s 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment was a battle-tested outfit that had performed well. Formed at Fort Benning, Georgia, in July 1942, the 507th arrived in Northern Ireland in December 1943 and was attached to the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division, training in England for the Normandy invasion on June 6, 1944. The 82nd was short one regiment because its organic 504th PIR had taken heavy casualties during the Italian campaign. Once the 504th was reconstituted and reunited with its parent division, the 507th was transferred to Maj. Gen. William M. Miley’s 17th Airborne Division.

Anxious for their next combat assignment, not all of the 507th’s paratroopers applauded the regiment’s transfer. “This move had a decidedly depressing effect on morale within the regiment,” said then-Major Paul F. Smith, commander of the 1st Battalion of the 507th. Although the troops were unhappy that they had been stripped from an experienced airborne division that had distinguished itself during Operation Overlord and put into an inexperienced division that had yet to make a combat jump, Colonel Raff did everything possible to correct the situation.

“By December [1944] morale had been restored and replacements received and brought up to operational speed by an intensive training program,” Smith said. “The regiment was ready and eager for another airborne operation. But that was not to be. The German push in what is now known as the ‘Battle of the Bulge’ had the effect of vacuuming the 507th, indeed the entire 17th Airborne Division, into the Ardennes area. For us, this was a miserably cold, high-casualty, straight infantry-type operation for which the regiment was neither organized nor equipped.”

Following the Bulge, during which the 17th and the 507th were mauled by the massive and unexpected German offensive but still fought back heroically, the paratroopers were pulled off the line to rest and refit and wait for a new opportunity.

As the 507th withdrew to a tent camp at Châlons-sur-Marne, France, in February 1945, few of the troopers knew that they would spearhead the airborne invasion of Germany in a few weeks. Suspicions began to grow quickly, however, as little time was given to cleaning and repair of combat gear before field training was underway.

While three-day passes to Paris were had by a few lucky troopers, hard, realistic training was the rule of daily camp life. New troopers were received into the 507th to replace the 700-plus casualties taken during the Bulge, and rehearsal jumps were conducted using the Marne River to simulate the Rhine.

Varsity would mark the first use of a new aircraft, the Curtiss C-46 Commando, for deploying airborne troops. The C-46 could carry twice as many paratroopers as the C-47 Dakota (36 versus 18). Furthermore, the C-46 was faster and had doors on either side of the fuselage, allowing troops to exit the aircraft quickly. The one drawback for Varsity planners was that only 75 C-46s would be available, and most soldiers would still be carried by the older, slower C-47s.

Coutts’ 513th PIR was assigned to the new aircraft, and the men of the 507th grumbled that they did not get the new planes, although, as events would soon show, they would be the lucky ones.

The Plunder Plan

The plan called for the 15th Scottish Division of British XXX Corps to launch Plunder by crossing the Rhine by boat in the predawn hours of March 24, 1945. Ten more divisions would follow. A few miles to the south, the 120,000-man U.S. XVI Corps, consisting of the 30th, 79th Infantry, and 8th Armored Divisions, among others, would do the same.

The next phase of the operation would be Varsity—the dropping of the two airborne divisions north of the city of Wesel on the northern fringe of the sprawling Essen-Düsseldorf-Dortmund industrial complex and 4 to 6 miles east of the 15th Scottish Division’s assault crossings.

Varsity called for airborne forces to be dropped almost all at once at landing zones as close as possible to their objectives. The 17th Airborne would land in the southern portion of the drop zones while the British 6th Airborne would drop in the northern area. The drop would also take place during daylight hours, which had the disadvantage of exposing the slow-flying gliders and transport aircraft to German antiaircraft fire.

Realizing the danger, however, the planners chose a daylight drop because it would facilitate a quick linkup of forces and avoid the still active night fighters of the Luftwaffe, as well as avoid the problems associated with the night drop that caused so much chaos during Overlord.

Ridgway was concerned about a repeat of the previous September’s Operation Market-Garden, when unexpectedly heavy German resistance delayed XXX Corps’ advance on the ground and forced the airborne forces to hold their objectives for longer than planned, leading to a debacle. Dempsey assured Ridgway that the linkup of his Second Army with Simpson’s Ninth Army would occur quickly, with two divisions reaching the airborne forces in no more than 48 hours. Ridgway, however, remained skeptical of Dempsey’s promise; he blamed much of Market-Garden’s failure on Dempsey’s lack of aggressiveness in pushing British ground forces forward.

The Varsity drop and landings would put the parachute and glider troops behind the German forward riverline defenses and squarely on top of their reserves and supporting artillery. The German II Parachute Corps, with the understrength 6th, 7th, and 8th Parachute Divisions, was the principal defense force in the Wesel area.

The 17th Airborne Division’s threefold mission was to seize, clear, and secure its area with priority given to the high ground east of Diersfordt and bridges over the small Issel River north of Wesel; protect the Corps’ right flank; and make contact with the two river-crossing forces and British 6th Airborne.

The 507th, nicknamed “Raff’s Ruffians,” was made a combat team (CT) by the attachment of the 464th Parachute Field Artillery (PFA) Battalion and Battery A, 155th Antiaircraft Battalion. The 507th CT would lead the entire XVIII Corps assault. It was to seize its objective, assist the Rhine crossings of the 15th Scottish Division, and assemble along the eastern edge of the woods when junction with the assault units was made. It would also capture a castle at Diersfordt that intelligence said was the headquarters for German units in the area. Drop time was set for 10 am on March 24.

After four weeks of training at Châlons-sur-Marne, the 507th was on its way to being sealed into marshaling areas at airfield A-40 at Chartres, southwest of Paris, and A-79 at Reims, east of Paris.

For several days, maps and aerial photos of the airborne invasion area east of the Rhine were updated. Detailed terrain boards of the Varsity drop area and plans for the assault were studied and restudied by all troopers. Equipment was checked and rechecked. The time between briefings, eating, and sleeping was filled with physical conditioning, sports, movies, and jesting about Axis Sally’s radio broadcast prediction that the jump they were about to make would end in bloody failure.

The Lift

D-day, March 24, 1945, dawned clear and sunny as the first three aircraft transporting Colonel Raff and his regimental command group lifted off from A-40 at 7:17 am. In the next plane, leading 1st Battalion assault elements, were battalion commander Major Paul F. Smith, B Company commander Captain John Marr, and Major Floyd “Ben” Schwartzwalder, who would be spearheading the 17th Division military government efforts. Completing the 41-plane first serial was the remainder of the 1st Battalion, slated to go into regimental reserve north of the drop zone (DZ) upon landing.

Next in line with 45 planes from A-79 was Lt. Col. Charles J. Timmes’ 2nd Battalion, which was tasked with taking positions west of the DZ and assisting the British river crossing. With another 45 planes from A-79, Lt. Col. Allen Taylor’s 3rd Battalion began taking off behind 2nd Battalion with the mission of seizing and holding the high ground northwest of the DZ at Diersfordt.

The 17th Airborne planes, all headed for DZ W, would require 21/2 hours to reach the drop zone. Coutts’ 513th PIR would follow immediately, and then additional C-47s, towing 906 CG-4A Waco gliders, would bring in Pierce’s 194th Glider Infantry Regiment.

The last planes took off just before 9 am. The airborne lift included a total of 9,387 paratroopers and glider-borne soldiers carried aboard 72 C-46s, 836 C-47s, and 906 CG-4A gliders. This, combined with the British airborne armada of nearly 800 transports and 420 gliders carrying over 8,000 soldiers, stretched nearly 200 miles and took 37 minutes to pass a given point.

The aerial panorama unfolded as the skytrain of IX Troop Carrier Command moved toward the showdown on German soil. Below, the peaceful French and Belgian landscape was greening and farmers were already in the fields. The zigzag pattern of old trenches came into view—mute testimony of another world war that had engulfed humanity a generation earlier.

Fighter planes protecting the air column cavorted about doing barrel rolls and other aerobatics. Brussels became visible, then a thick haze of smoke from generators, used to screen the British river crossings, enveloped the air column as it crossed over the release point for its final leg to the drop zone.

The unnamed author of the 507th’s official Historical Report–507th Combat Team–Operation Varsity noted that the view from the planes “showed a beautiful European landscape, colorfully roofed hamlets, large industrial areas, and cozy little farms. War seemed far away. [At] the 20-minute warning, the men stood up and hooked up. It won’t be long now.

“Suddenly, as if a curtain had been lifted, the view changed. The countryside was beaten and gray, barren, a graveyard look, the smoke of battle wafted drearily upward, shots could be heard; we were approaching the Rhine.”

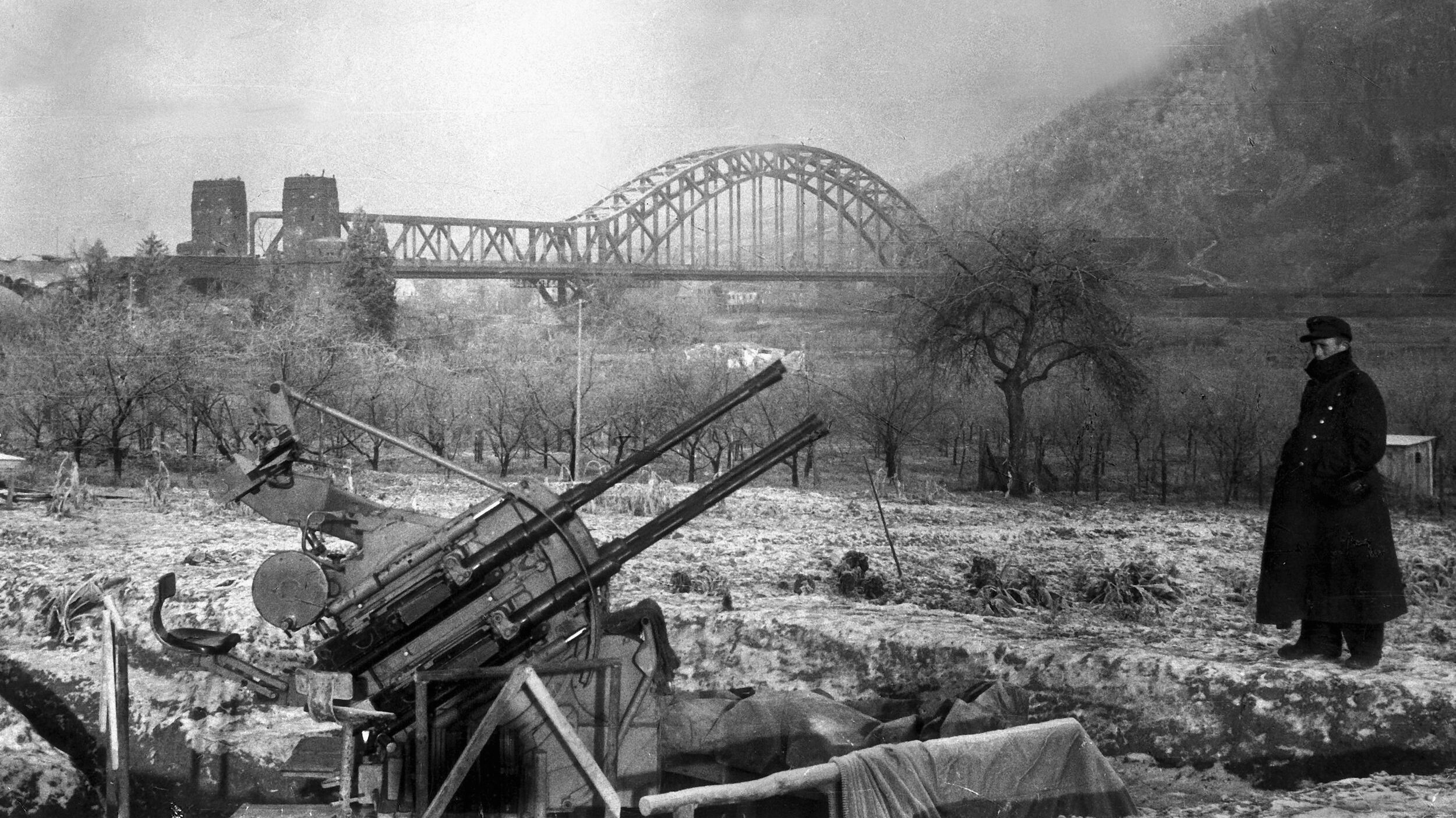

At once the air was filled with hundreds of explosions from flak guns positioned behind the German riverline defenses—explosions meant to bring down the low-flying troop-carrier columns. Axis Sally’s claims to have detailed knowledge of the Allied airborne plan, along with her dire predictions about the outcome, seemed to have credibility as flak-damaged planes could be seen spilling out paratroopers while veering sharply, losing altitude, and streaming flames.

Just before the jump, Colonel Raff, a devout Catholic, said a silent prayer. “I was alone standing in the door of the plane looking down at the river passing beneath the plane, smoke partially obscured my view. At that moment, I said a prayer to the infant Jesus, the Little Flower: ‘Flower, in this hour show Thy power.’ The prayer was given to me by my sister, who was a nun. I said the prayer before every jump. A split second after I said the prayer, the green light came on.”

The Drop

At 9:50 am the men in Raff’s C-46 jumped out behind their commander. As the regimental command group and the men of the 1st Battalion left their planes, they were confident that Colonel Joel Crouch’s Pathfinder Group, in whose planes they rode, had brought them over DZ W, two miles north of Wesel. En route to the DZ, Crouch had bet Raff a case of champagne that the drop would be made squarely on the DZ.

The anonymous author of the 507th’s official report captured the moment: “For an instant the big river flashed beneath us, ack-ack and anti-aircraft fire rattled and cracked around the planes; the green light, GO! A rush of air, a jerk, a look around, a jolt, we were on the ground and the 507th Parachute Infantry had been committed.”

Raff noted, “As I looked down, I saw several objects below me. The first thing that caught my attention were several German soldiers on the ground with rifles in their hands, looking up. The second thing I noticed was a heavy equipment bundle that was swinging back and forth as it descended toward the ground. The bundle saved my life because the Germans thought it was a bomb and disappeared into the cellar of a nearby house.

“I landed in the chicken yard behind one of the homes. There were no chickens, since they had all been eaten. The loneliness was numbing as there wasn’t another paratrooper in sight. But soon I joined up with others in the 507 and I was astonished to see Germans to our right in the process of pulling artillery behind us. Needless to say, they were soon captured.”

Raff won the champagne bet easily as Crouch’s group missed DZ W with all 45 planeloads, dropping them to the northwest of Diersfordt, 2,500 yards from DZ W and atop a host of German artillery positions in the 513th CT’s area of responsibility. The German gunners inflicted some casualties during the descent, but the defense collapsed quickly in the face of return fire from organized groups of paratroopers.

The story was different on DZ W, where Timmes’ 2nd and Taylor’s 3rd Battalions and the 464th PFA Battalion landed in the midst of heavy fire from machine guns, mortars, and small arms that killed many paratroopers in the air, at touchdown, during assembly, and while attacking German strongpoints.

The 507th’s official report said, “Several planes were destroyed in the air. At least one plane crashed on the DZ with all aboard. Other planes burned after dropping their personnel. In some, the Air Corps personnel escaped; in others, charred bodies gave stark testimony to the devotion of duty performed by good soldiers. Some parachutists were hit during their descent, some were killed in their harnesses, and others while scrambling off the field.”

Immediately behind Colonel Raff in the first plane was A Company sergeant and bazookaman Harold E. Barkley. During the drop, he lowered his bazooka bag on its tether, slipped his parachute to the side to avoid an equipment chute, and saw himself headed toward a hole in a barn roof. Helpless to avoid it, he uttered a prayer and came to an unexpected landing in the hayloft inside. When the door burst open below, he was certain that it was the enemy but then someone shouted, “Hold it, that’s Barkley!”

Another A Company man, John H. Nichols, remembered the skill and courage of the troop-carrier pilots as they brought his plane, being buffeted by flak, in for the drop at 400-600 feet. He was shocked at the sight of some of his buddies hanging dead in their chutes from the bare tree limbs at the edge of the woods.

This was echoed by H Company’s Pfc. Gordon Nagel. Cut and blinded by blood in his eyes after being hit across the face with his own submachine gun when he received the shock of his parachute opening, Nagel did not see his landing. As he regained his sight on the ground, he saw the dead bodies of three paratroopers, all close friends, sprawled nearby.

Private First Class Bob Baldwin, H Company, also had a horrifying experience. During the descent, he saw his platoon sergeant disintegrate in midair when his bag of explosives was hit by a German bullet. He also remembered pulling himself over a seven-foot-high fence while German gunners tried to kill him.

Upon hitting the ground, D Company’s Paul N. Peck heard buzzing sounds reminiscent of bees. He started to run and fell with his chute still attached to his harness. Looking down, he noticed bullet holes in his jacket and trousers and quickly realized that the buzzing sounds were German machine-gun bullets tracking him across the DZ. Without helmet, rifle, or grenades, Peck ran to safety and then helped a mortar crew fire some rounds. He soon found a carbine and took up the duties of scout.

Staff Sergeant Joe Faust, C Company, fell victim to the white flag ruse so often used by the Germans. About 50 flag-waving Germans were in the woods and, as Faust advanced to take them prisoner, the flags were dropped and guns were drawn. In the hail of lead that followed, Faust went down with a bullet wound in the thigh.

Individual acts of heroism took place all over the area. One particularly conspicuous one involved G Company’s Private George Peters, from Cranston, Rhode Island. After landing near Flüren, the 20-year-old Peters and 10 other troopers were fired upon by a German machine-gun crew, supported by riflemen, while struggling to free themselves from their parachutes. Pinned down, Peters, without orders and armed only with a rifle and a few grenades, stood up and charged the gun position 75 yards away.

He was hit and knocked to the ground by a burst from the German gun but got to his feet and continued his charge. Hit again and unable to rise, he crawled directly toward the machine-gun nest that had wounded him. In his dying moments, he hurled a grenade that destroyed the gun crew, caused the riflemen to flee, and saved the lives of his fellow troopers. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Such acts of bravery were making a difference. The 507th’s history said, “During this period the enemy seemed to be completely demoralized and disorganized. Some gave up without fighting, although they had the advantage of ground, prepared positions, combined with the fact that the paratrooper is comparatively helpless for some seconds after he hits the ground. Others fought hard and ferociously, inflicting casualties on the DZ and in engagements immediately beyond the DZ. Our positions were beginning to take form, but as yet the Germans did not seem to be maintaining any line.”

Although they had landed in the wrong area, Colonel Raff’s group and Lt. Col. Paul Smith’s 1st Battalion took the initiative and began battling the enemy wherever they found them. A group of about 150 troopers assembled with Captains Murray Harvey of Headquarters Company, John Marr of B Company, and John T. Joseph of C Company headed north to assemble in the woods and began clearing German artillery crews from the objective of 2nd Battalion, 513th Combat Team.

While Smith’s troopers were attacking and destroying the enemy positions, Raff’s men knocked out a machine-gun nest and dug-in infantry on their way to the assigned regimental objective—an old castle at Diersfordt.

The official Army history noted, “Spotting a battery of five 150mm artillery pieces firing from a clearing, Raff and his force detoured to eliminate it. They captured both the German artillerymen and the guns and spiked the guns with thermite grenades. By the time Raff’s paratroopers reached the vicinity of Diersfordt, they had killed about 55 Germans, wounded 40, and captured 300, including a colonel.”

The 37-year-old Raff, who had been at war ever since he parachuted into Oran, Algeria, in November 1942, was much beloved and respected by his men. One of them said, “If we were ordered to invade Hell, I’d have followed him there.” Even General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in Western Europe, had high praise for Raff, saying ‘”The deceptions he practiced, the speed with which he struck, his boldness and his aggressiveness, kept the enemy completely confused during a period of weeks.”

The Battle for the Castle

Reversing direction, Raff’s group turned southeast and by 11 am arrived at the northwest edge of the grounds of the Diersfordt castle, a fortress that dated from 1432 and was being used as a headquarters. The most determined enemy troops, and the last to fall in the 507th’s area of responsibility, were entrenched in and around Diersfordt Castle.

Here, the Raff group, along with Harvey’s, Marr’s, and Joseph’s men, were rejoined by Major Smith, who had collected about 200 paratroopers, the bulk of them from A Company commanded by Captain Albert L. Stephens.

Smith and his group had eliminated some enemy positions when they were fired on by German tanks coming from Diersfordt Castle. The Army’s official history said, “Two German [Mark IV] tanks emerged from the castle and headed down a narrow forest road toward the waiting paratroopers. An aptly placed antitank grenade induced the crew of the lead tank to surrender, whereupon a tank-hunter team armed with a 57mm recoilless rifle set the second afire with a direct hit, the first instance of successful combat use of the new weapon.”

With about 90 percent of his battalion available and under orders from Raff to continue the assault on the Diersfordt stronghold, Smith launched his attack.

The Army’s official history continued: “While two companies laid down a base of fire from the edge of the forest against turrets and upper windows, Company G entered and began to clean out the castle, room by room.”

With a lot of rooms to clear and after two hours of nonstop fighting, Captain Bill Miller’s G Company began its assault on the turret of the old fortress’s tower, where a number of German officers held out.

Wounded during the battle and unable to continue in the fight, Captain Miller passed an American flag to Staff Sgt. Bill Consolvo. Earlier that morning, before takeoff, Miller had displayed the flag to the G Company troopers and vowed that it would be flying high over Germany before day’s end. Now it was up to Consolvo.

When a German colonel in the castle turret was severely burned by a phosphorous grenade, the holdouts came rushing out and surrendered. The castle fight yielded nearly 500 prisoners (including a number of senior officers from the German LXXXVI Corps and 84th Infantry Division), five tanks, and a host of other weapons. Consolvo climbed the turret, unfurled the flag, and secured it to the highest point. G Company troopers, busy consolidating their positions, stopped long enough to give a proud salute to the victory flag.

The hoisted flag was a fitting punctuation for the 507th’s last major skirmish of March 24. That evening, the regiment, with Diersfordt and the castle firmly in its grasp, sent out patrols and made contact with the British 1st Commando Brigade in the ruins of bomb-ravaged Wesel.

Compared to other units in the 17th Airborne Division, the 507th Combat Team’s casualties had been light—about 150 killed and wounded.

As the battle for the castle raged, other companies of Timmes’ 2nd Battalion continued fighting their way through the area, reducing enemy strongpoints one

by one. Nearby houses used for German gun emplacements also had to be taken. Once the woods southwest of Diersfordt were cleared, F Company contacted the British river-crossing forces at about 2:30 pm.

The 464th PFA followed the 507th onto DZ W and, to the surprise of the Germans, began reducing points of resistance on the DZ with direct fire from its 75mm pack howitzers. With steady accumulation, 10 of its 12 howitzers were in support of the 507th within three hours. Shortly before 3 pm, regimental headquarters was established north of the town of Flüren and south of Diersfordt.

Against a powerful German force that had every advantage of terrain and choice of position, Raff’s CT had accomplished all its missions with distinction. It had converted initial adversity into the opportunity of an early assault on its main objective.

In the 507th’s sector, only minor points of resistance were left to be mopped up. A firm link with the British forces had been forged, and bridges across the Issel River had been taken for the drive eastward.

The 513th Arrives

The arrival of the 507th had, of course, brought German antiaircraft defenses to full alert, and the gunners who had survived Raff’s initial assault were waiting when the planes carrying the 513th PIR approached the drop zones. These gunners now turned their attention to the low-flying transport planes and descending paratroopers overhead.

Almost immediately, a fatal C-46 design flaw became tragically apparent. The planes lacked self-sealing fuel tanks. If a fuel tank were punctured, high-octane aviation gas would stream along the wings toward the fuselage. All it took was a single spark to turn each plane into a flying inferno. German 20mm incendiary rounds proved extremely lethal, and several damaged aircraft were set ablaze.

Ridgway later reported that the heaviest losses during Varsity came in the first 30 minutes of the 513th’s drop. Nineteen of the 72 C-46s were lost, with 14 going down in flames, some with paratroopers on board. Another 38 were badly damaged. Many soldiers wounded during the flight to the drop zones chose to jump and take their chances rather than remain in the dangerously flawed aircraft. After Varsity, Ridgway issued orders prohibiting the use of C-46s in future airborne operations.

The C-46 carrying the 513th’s commander, Colonel Coutts, was hit by long-range antiaircraft fire and was ablaze as it crossed the Rhine. Coutts’ stick managed to hook up one wounded soldier and shove him out of the plane before the rest followed.

Upon hitting the ground, Coutts and his men came under intense small-arms fire, and many were killed and wounded as they descended. Suddenly, the drop zone was being invaded by hundreds of British paratroopers, and British gliders soon began landing all around. At first Coutts thought that the British had landed in the wrong zone, but soon he realized that his regiment had been mistakenly dropped in the British sector, about a mile and a half from Hamminkeln.

After assembling under heavy fire, the battalions of the 513th fought their way south toward their assigned objectives, destroying two tanks, a self-propelled gun, and two batteries of 88mm guns in the process. One battalion reached the Issel River, the easternmost of the first day’s objectives. The 507th, however, also having been dropped in the wrong area, had already seized many of the 513th’s objectives by the time it arrived.

As the 513th’s Company E advanced south, it was raked by heavy fire from enemy machine guns set up in some buildings; one platoon was immediately pinned down. With complete disregard for his own safety, 21-year-old Pfc. Stuart S. Stryker of Portland, Oregon, rose and charged toward the enemy. He was cut down by enemy fire, but his actions rallied others in the company and shortly thereafter they overran the German position, taking more than 200 prisoners and freeing three American airmen who had been shot down and captured. Stryker was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions. He was the second 17th Airborne trooper to earn America’s highest military award during Varsity.

The 513th’s supporting artillery, the 466th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion commanded by Lt. Col. Ken Booth, landed on the correct drop zone southeast of Hamminkeln, but enemy fire there was heavier than that faced by the infantry. German fire took a great toll among the battalion’s officers, and many artillerymen were forced to fight as infantry while others assembled their 75mm pack howitzers and gathered ammunition and equipment off the drop zone.

Despite the intense fire, the artillerymen assembled several of their guns within 30 minutes and were soon blasting away at German targets. By noon, the 466th had captured 10 German 76mm guns and was providing artillery support for the 513th Parachute Infantry.

By around 3:30 pm, the 513th had taken all its objectives along with some 1,500 prisoners. Operation Varsity’s airborne phase was all but over.

On D+1 (March 25), the 507th’s 3rd Battalion was in reserve, as were the 1st and 2nd Battalions with tank-destroyer guns attached. They cleared enemy pockets from the area between the 507th, the Scottish Commandos at Wesel, and British forces making a new crossing of the curving Rhine, south to north, about 5,000 yards west of Wesel.

This put the 507th on Phase Line London, facing east. The airborne drop had collapsed German defenses east of the Rhine. To prevent the enemy from building a defense elsewhere, speed was of utmost importance. A series of Phase Lines (dubbed London, New York, Paris, Boston, etc.) were laid out to the east toward the ancient city of Münster (founded in ad 793), the cultural capital of the Westphalia region, to coordinate the Allied advance.

The British Second Army and the U.S. Ninth Army would attack eastward with the Lippe River separating them. Maintaining contact between the two armies would be the responsibility of the U.S. 30th Infantry Division and the 17th’s 507th CT. With a company of tanks added to its arsenal, the 507th stood on Phase Line London, ready for the upcoming sprint.

The Dash to Münster

At three minutes past 9 am on March 26, the 507th CT began its advance to Phase Line New York just beyond a north-south autobahn with the 1st and 2nd Battalions in the lead; the goal was Münster, 50 miles away. The 507th advanced against sporadic resistance in what was to become the most prevalent form of the Germans’ delaying tactic, one or two self-propelled guns and a platoon or so of infantry equipped with machine guns and mortars.

These small, highly mobile teams would open fire from concealed positions, force deployment of the advancing troops, then scoot to the rear to repeat the tactic at another village, road intersection, bridge, or other critical point.

The German tactics were effective to a certain extent, but the enemy was overwhelmed by the speed of the Allied advance. As the 507th kept up the pressure to the towns of Peddenburg, Schermbeck, and Wulfen, the battalions leapfrogged from reserve to frontline duty, using trucks on occasion to speed the advance.

At 11:04 am on the 27th, the 17th Division’s commanding general, Maj. Gen. William M. Milley, called for pursuit tactics, which meant that units should step up the pace, bypass points of resistance, and go for deep objectives. In keeping with pursuit tactics, the British 6th Guards Armoured Brigade, with the 513th CT soldiers riding its tanks, passed through the 507th on March 28 and sped off to Haltern.

The push was relentless day and night with only short respites at key coordination points, and it became difficult for commanders to keep up with the forward progress of their frontline units. On one occasion Colonel Raff and his bodyguard, Cleo Crouch, went forward to find H Company’s Captain Stephens, who was reported to be out front trying to locate a German self-propelled gun. They moved forward to the top of a hill but failed to find the captain. As they turned about to retrace their steps, a dud from the unseen German self-propelled gun crashed at their feet. As the two men ran for the woods, the gun spit out three more rounds that exploded harmlessly in the trees.

On March 29, the 507th CT, having fought its way over 25 miles in four days, was detached from the 17th Division, attached to XIX Corps, and sent to Haltern, between Wesel and Münster, to relieve the Guards Armoured Brigade. By this time German soldiers were streaming to the west by the hundreds, many in unit formation, in an attempt to stop the Allied advance.

At Haltern the 507th fought off counterattacks, many from the south, rooted out pockets of resistance, and searched for German military installations in the city and outlying suburbs, where it flushed out pockets of stubborn enemy soldiers. And Münster had plenty of military installations. It was the home of the VI and XXIII Corps as well as the XXXIII and LVI Panzer Corps, not to mention 24 infantry and armored divisions.

After Münster fell to the 17th Airborne Division (now under the command of Maj. Gen. Alvan C. Gillem) and 6th Guards Armoured Brigade on April 2, XIX Corps relinquished control of the 507th back to the 17th Airborne Division, and it was trucked to Münster, where battalion sectors were assigned for cleanup and protection duties.

The Battle of the Ruhr Pocket

Early on April 6, the 507th’s 1st and 3rd Battalions performed a night relief of the 315th Infantry Regiment and a battalion of the 314th Regiment, 79th Infantry Division along the Rhine-Herne Canal on the southern edge of Bottrop, northwest of Essen. Here the CT was tasked with guarding four factories. Curfew and a policy of a minimum number of troopers on duty were adopted.

This respite gave time for bathing, delousing, clothing change, equipment repair, restoring basic ammunition loads, and rest from the rigors of the past 12 days. Combat was not over, however, as the enemy dished up a fairly constant menu of sniper, machine-gun, artillery, and mortar fire. The troopers along the canal returned the fire and, using assault boats issued to each battalion, systematically patrolled the German side.

At 3 am on April 7, the 79th Division attacked south across the canal from positions to the left, while the 507th conducted a successful demonstration to draw German fire away from the 79th. As that action got underway, 3rd Battalion forged a small bridgehead across the canal on the right side of the 507th zone with two platoons from I Company.

At 9:55 that evening, the 3rd Battalion had captured 11 prisoners and dispatched a combat patrol, led by H Company’s 1st Lt. Bartley E. Hale and accompanied by Regimental S-2 (Intelligence) Captain George J. Roper, that clashed with a strong German force. Roper was killed, and the patrol disappeared. Efforts to reach Hale and his men were unsuccessful.

The next day, Battalion S-2 1st Lt. Donald C. O’Rourke flew over the point of last contact and, seeing 12 guarded paratroopers lined up against a wall, presumed them to be part of the lost patrol. When the patrol was freed after the German collapse in the Ruhr Pocket, it was learned that it had exhausted its ammunition and had to surrender.

On April 8, 2nd Battalion attacked across the canal and captured 38 Germans while reaching its objective on the right flank of the 79th Division. Meanwhile, Taylor’s 3rd Battalion hung onto its bridgehead under increasing fire and counterattacks. The 1st Battalion reverted to reserve.

The Germans still had plenty of fight left as the 1st Battalion discovered when it came out of reserve the following morning and passed through 2nd Battalion on the front lines. When 21-year-old Pfc. Dante Toneguzzo’s platoon from C Company was pinned down by fire from two mutually supporting pillboxes near Essen, he arose on his own initiative in the face of withering enemy fire and stormed the nearest pillbox alone. His grenade killed two and caused nine Germans to surrender.

Then, still alone, Toneguzzo unhesitatingly moved against the second pillbox, again exposing himself to intense machine-gun and sniper fire. He threw another grenade, which killed one enemy soldier and forced five others to surrender. For this selfless act of heroism, the native of Columbus, Ohio, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Heading East

By April 10, the tempo of Allied operations began to step up as the Germans began withdrawing, leaving cities open in their wake. All 507th battalions linked up south of the Rhine Herne Canal. At 2:30 pm, two five-man jeep patrols entered Essen, home of the renowned Krupp Steel munitions works, and returned at 5 pm to report no resistance in the bomb-shattered city. By 2:30 the next morning, the 507th was holding assigned sectors in Essen.

With little rest, the CT was on the move again by 7 am and in Mulheim with a small bridgehead west of the Ruhr River by noon; the 194th Glider Infantry Regiment followed shortly thereafter and relieved the 507th, which was ordered to attack Duisburg, one of the major industrial cities of the Ruhr area. Although the orders were soon cancelled, the cancellation came too late to stop two jeep patrols that reached the edge of the city and found that it was ready to surrender.

At 3 pm, the German military commander of Duisburg, realizing further resistance was futile, surrendered to the 2nd Battalion’s S-2, 1st Lt. Harley Bennett. An hour later Colonel Raff signed the formal acceptance of the German surrender. At midnight, B Company of the 1st Battalion entered the quiet, shattered city and established control.

It was apparent that German resistance in the West was rapidly collapsing and, despite Hitler’s demands that all Germans fight to the death, many local commanders were choosing surrender over annihilation.

The 507th took up positions along the Ruhr River south of Essen from Kettwig to Dalhauser. The pressure of other American forces pushing up from the south caught the Germans in a huge vise.

Almost unbelievably, here and there some German units were refusing to give up and continued fighting. Some German units seemed focused on retaking bridges over the Ruhr, especially the one at the small village of Werden, where Timmes’ 2nd Battalion had established a bridgehead.

After April 16, the Germans delivered concentrations of heavy-caliber fire and launched counterattacks to wipe out the bridgehead, but each time they were repulsed. On the 16th, gunfire could be heard from the south and German guns could be seen firing. At 6:55 am, F Company’s 2nd Lt. Thomas J. Danes moved forward to link up with Task Force Leonard of the 13th Armored Division. But the fighting was almost over.

At 8:45 am on this last day of combat for the CT, E Company was contacted by the 13th Infantry Regiment, 8th Infantry Division, the same division that had relieved the 507th of its combat duties in Normandy nine months earlier, and the guns went silent.

Hostilities Cease

While open hostilities were at last over for the 507th, it still had urgent military duties to perform. For the next eight weeks, until a more permanent occupation structure could be put in place, the mission of the regiment was twofold: It was to administer military government to more than one million Germans in the Essen Zone and provide care for about 25,000 displaced persons (DPs). The zone was divided into subzones that were administrated by the battalions; Colonel Raff was the zone commander.

The Americans’ almost insurmountable task was to provide life-sustaining services to the entire population. The DPs were representative of nearly all the nationalities of Europe, each with unique problems to be solved. Most of the DPs were concentration camp inmates used as slave laborers for the huge industrial base of the German war machine, and their animosity toward the Germans presented special problems.

To facilitate care and repatriation, self-governing DP camps were set up in the subzones, but military governance was not an endeavor in which the regiment had spent a great deal of training. Disciplined efficiency was needed for effective and compassionate administration of this mix of the newly vanquished and the newly freed. As expected, the regiment performed these final military tasks with distinction.

On June 17, 1945, with the war won and with the Essen area in the British zone of occupation, the 507th was relieved by British forces and prepared to leave Europe. During its time in combat since the previous June, the regiment had suffered 423 men killed, 893 wounded, and another 496 listed as missing.

While performing spectacularly in its first combat airborne assault, the 17th Airborne Division alone lost 159 killed, 522 wounded, and 840 missing (many of whom later turned up to fight again). British losses among the 6th Airborne Division were even heavier. The IX Troop Carrier Command lost 41 killed, 153 wounded, and 163 missing. Fifty gliders and 44 transport aircraft were destroyed, another 332 transport planes were damaged, and only a few of the gliders were salvageable.

While tactically successful, Varsity brought many questions, especially about whether or not it was militarily necessary. In his postwar memoir, A Soldier’s Story, General Omar Bradley contended that the Germans had diverted the bulk of their forces east of the Rhine to counter the breakthrough at the Remagen bridgehead, leaving only weak forces around Wesel.

He added that if Montgomery had crossed the Rhine with the same dash and élan that the commands of Generals Courtney Hodges and George S. Patton had or had allowed Simpson to do so with his Ninth Army, Varsity would not have been necessary. To Bradley, Varsity was typical Montgomery overkill. Other officers had even harsher words, claiming that Montgomery used airborne forces to simply “put on a good show” and to further to his own reputation as a military genius.

Whether or not Operation Varsity was actually necessary will, no doubt, continue to be debated, but that in no way diminishes the courage and resourcefulness demonstrated by the soldiers who took part and, in the process, wrote another chapter in the history of the U.S. Army and the American airborne forces.

After returning to the States, the 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment was deactivated at Camp Miles Standish, about 40 miles south of Boston in Taunton, Massachusetts, on September 15, 1945. Once a proud and highly skilled regiment with 21 months overseas, four campaigns, and two combat jumps to its credit, the 507th devolved into a collection of footlockers filled with paper and consigned to a records depot.

The 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment was reactivated in 1948, served for a year, and then went dormant again. In 1985, a full 40 years after it helped secure final and total victory in Europe, the 1st Battalion of the 507th was brought back to life. It continues to serve proudly, training future paratroopers at Fort Benning, Georgia. The legend of Raff’s Ruffians lives on in glory.

My father, Albert A. Kurtz, 33-258-031, was a member of the 507th PIR, 2nd Bn, “D” Co. He landed in Normandy, fought in the Battle of the Bulge, and this operation. Like many WW-II vets, he never discussed where he was, engagements, or wrote anything down. I’m trying to get detailed information of where he was and what he did. I tend to follow/trace 2nd Bn., but I’m not sure that’s 100% correct at all times. Operation Varsity – He was on Tail No. 100751, chalk No. 65. This gives me some ideas & w/ Google, it’s great to map it all out.

Any help would be greatly appreciated.

Thanks and R/S Alex G. Kurtz; 937.269.8675

Hello, Mr. Kurtz

My name is Thierry Minsart, career soldier, and I live in the beautiful region of Bastogne in Belgium.

I am preparing a book on the 17 Airborne and more precisely on the period of January 1945 in the region of Flamierge and its surroundings where I live in a small village called Tronle.

I find that some units like the 193,194 Glider and 507,513 Pir, have been forgotten in many history books during this period! Fortunately, the Varsity mission to Germany has brought them back to life.

I intend to make a history and military technique book about these units during the battle of DEAD MAN’S RIDGE (my region)

Give me some info with documents and I will look to see if I can find it in but daily and campaign report.

You have my mailbox: thierry [email protected].

Take care of yourself and your family.

Sincerely, Thierry