By Reverend E. Gage Hotaling

BACKSTORY: The Reverend E. Gage Hotaling, the son of a Baptist minister, was born in Wellsville, New York, on January 21, 1916. He grew up in Providence, Rhode Island, and graduated from Brown University, class of 1935, and Andover Newton Theological School in 1940. After graduating in 1944 from the Naval Chaplains School in Newport, Rhode Island, he joined the U.S. Navy at the age of 27. Serving as a chaplain in the Graves Registration Section of the 4th Marine Division, he spent 26 days on Iwo Jima—a vicious island battle that claimed the lives of over 6,800 Americans and 20,000 Japanese.

His son, Kerry, who provided this magazine with excerpts from his father’s war diary, said that his father “felt that he would not be able to preach to this generation of people if he did not experience what they were going through.” The chaplain passed away in May 2010 after a long life preaching in many parishes in Massachusetts.

This excerpt from his diary begins in January 1945, as the 4th Marine Division, part of a larger task force of 70,000 Americans, prepared to depart Hawaii for the Japanese-held island of Iwo Jima.

The Diary of Reverend E. Gage Hotaling

January 26, 1945

Went ashore on my last liberty…. I went down to Waikiki where I had lunch. When I looked at the menu I saw they had clam chowder and sirloin steak. I had them both and then finished my dinner with a bottle of milk. Previous to getting the milk, I had a chocolate milk shake. That was the best dinner I had had in ages, and my bill came to only $1.65. The steak was rare and cooked just right to suit my taste. Then with my belly full of chow, I went over to the beach and laid in the sand for a while before going in for a dip. It was a delectable experience all told.

January 27, 1945

Today we left Honolulu Harbor and the ships carrying our division all set sail in a convoy for our destination, which we learned yesterday was to be Iwo Jima. So today was a typical day in the life of a Navy chaplain serving with the Marines on the way to an operation.

The day started at 0710 when Gus called me for breakfast. I had laid in the sack for a few minutes, then dressed and went in and had my orange juice, bacon, toast, jam, and coffee. Then went back and read for an hour. The rest of the morning was spent in writing some V-mail letters and shaving.

Then for noon chow there was a hamburg[er], brown-eyed peas, potatoes, salad, and lemon meringue pie. After lunch I read some more and then hit the sack for a couple of hours. Then a nice, warm shower pepped me up for dinner. Chow tonight was bean soup, roast beef, potatoes, string beans, tuna fish salad, and apple turnover. Then I had a couple of brownies from Dell’s Christmas package, changed from my khakis to my dungarees, got out the “riveter” to type a letter to Dell [Adell, his wife], read some more, and then hit the sack.

January 28, 1945

Today we had church service on the open deck for the first time, and it was very inspiring. The sun was shining beautifully and there were nearly 300 present.

The new censorship regulations were also announced today so that now we can write that we are on shipboard and on our way to combat.

January 30, 1945

To say that I am dreading combat is to put it mildly. They have already started to brief us about our target, and we know enough about it to know that a good many swell American boys are going to get hurt. Our intelligence tells us that there are some 13,000 Japs on Iwo and the island is very heavily fortified with all kinds of guns.

Even the doctors who have been with the 4th Division in other operations say this is going to be worse than any of the previous invasions. So I try to think of everything else I can except the operation, and I have so many plans for our postwar happiness, if, if….

February 1, 1945

We crossed the International Date Line today, so that we actually jumped from January 31st to February 2nd. We’re now right down in the tropics where it is warm all the time, day and night, and in our berthing compartments it is terribly stuffy, especially at night when everything is shut up, for we have to proceed in total blackout all night.

February 3, 1945

One of the things we have quite often on board ship as well as back in camp is avocado. It makes quite a delicious salad, and I’m getting to think of it as a real delicacy. You sort of have to get used to the taste of it just like ripe olives, but once you do it’s really good.

February 4, 1945

We had church at 10:30 this morning on the open deck and we had the largest crowd yet. The sun was pouring down with all its intensity, yet the men sat or stood and sweated and didn’t seem to mind it one bit. It was a real thrill for me to preach to that number of men crowded right around me.

In addition, we had a large number of officers present this morning for the first time, and it did my heart good to see them. Then after the sermon, Chaplain [Walter J.] Vierling held a communion service. When we were finished, we both had sweat through our clothes, because we always wear our black robes over our khaki.

My sermon today had some unexpected results. I received a large number of compliments for it, and one boy spoke to me afterwards to tell me that a small group had started to meet each night at 8:00 on deck for a hymn sing and prayer together. He asked me if I would come, and I said I’d be glad to, so I attended my first meeting tonight.

There were about 20 there and they sang everything from memory. Can you imagine 20 Marines going into battle sitting on the deck of a warship and singing “Jesus Wants Me for a Sunbeam”? Well, that actually happened tonight, for that was one of the songs that the boys sang. It was an hour of real inspiring fellowship. Now I’m looking forward to meeting with them each night. It will do me a lot of good, and help me during the lonely evenings.

February 5, 1945

We arrived at Eniwetok today and the first thing they did was to send the mail orderly ashore with a big sack of outgoing letters. And then, when he came back, he had several bags full of those precious morale builders. I’m rationing my mail and opening only a part of it each day, so as to make it last for those hectic days just before combat.

When I opened my birthday package from Dell, I passed the brownies around. They tasted very good, being only a little hard. Dr. Saint asked me if my wife made them and I said, “YOU BET!” Then he said, “Well, if you’re happily married, and she’s a good cook, that’s all that matters!”

February 6, 1945

After meeting with the boys in the fellowship group at night, I suggested that we meet each afternoon also from 1 to 2 on deck so that we could see what each other looked like in the daylight and really get acquainted. So we have done that.

Most of the boys are southerners and, of course, they are much better at going to church than the boys in the north. I have also started to teach them some of the choruses I used to use at Lime Rock [Connecticut]. So now I am beginning to feel that I am a little bit more useful than I have been. There is something definite to look forward to each day, the informal chat at 1, and the fellowship meeting at 8.

I have also had an interesting time talking with a Jewish boy, Nate Friedman, who is married to a Baptist girl and wants to be baptized and join her church. So I have met him several times and talked to him about Christian beliefs, baptism, etc.

February 8, 1945

I discovered that the dentist who bunks next to me, Dr. Edward MacFarland, grew up in the Mt. Lebanon Baptist Church in Pittsburgh and knows Uncle Albert very well. He has been fixing up my teeth. I’ve had 3 filled so far, with 1 more to go, and possibly another that he’s going to take an X-ray picture of. The equipment on this ship is the very best and the very latest. Think of having an X-ray machine right there, and taking a picture of anything that is not obvious, and then having it developed in five minutes!

February 11, 1945

We arrived at Saipan today and they brought us a big bunch of mail which made us all feel pretty good. This morning it was my turn to play the organ at church, and we just got through the service before it rained, which is the first rain I’ve seen in more than six weeks.

February 13, 1945

Spent a couple of hours taking a sun bath on the bridge deck. We’ve been cruising around off Tinian, and with our field glasses it’s lots of fun watching our ships and planes and shore installations, for they are plentiful out here, and it makes us feel good to see them.

February 16, 1945

Today they impregnated the clothing of all the Marines on the ship with insect repellent, so that when we land, we won’t have to worry about all kinds of insect bites. The spirit of the boys is good, and even though they are very near the target now, I haven’t detected any more signs of nervousness than were evident several weeks ago.

I’ve read 26 books since coming on board ship, 9 of them being Ellery Queen mysteries, 5 Charlie Chan, and 5 humorous novels by Thorne Smith.

February 17, 1945

Today has been marked by more feverish activities than any previous day. Since the landing is to be made day after tomorrow, the rations were passed out as well as ammunition for the rifles. I have to carry one too, although goodness knows what I would do with it if I had to use it. I’ve certainly got an awful mess of equipment, and I’m beginning to wonder how I’ll ever get it all ashore.

February 18, 1945

We had 2 Protestant services today, with over 300 present this morning and nearly 200 this afternoon. I presided this morning with [Earl D.] Sneary preaching, and then I assisted him in the communion service. This afternoon I preached, with Vierling presiding and taking charge of communion. It was a real challenge to know what to say, when you realize that some of the boys were probably hearing their last sermon.

I started out with my pictorial description of St. Paul walking to his death. Then I went on to say that he was the first Christian to make an amphibious landing in Europe, and I said he went through the same kind of hardships we are facing. I had 2 points, first, an amphibious landing tests a man’s courage to the very limit, and second, it tests his faith to the limit. The boys listened very carefully, and I think I pitched the ball over the plate. Hope so anyway.

Tomorrow is D-day, and I am scheduled to go ashore the day after, if the beach is cleared away enough so that they can land the support troops. Tonight’s chow was superb––tenderloin steak with all the fixings, and ice cream. Then tomorrow there will be an early breakfast of ham and eggs for those going ashore.

February 19, 1945

When I got up this morning and looked out, I saw Iwo Jima for the first time, all clouded in smoke because of the terrific naval bombardment which continued right up till H-hour at 0900. We were anchored some 6 or 7 miles offshore as were the other transports. There wasn’t much to do this morning, as all the assault troops had left the ship early. The medical department quickly transformed the officers quarters into a dispensary, for the casualties were to be put in our quarters.

The first casualties arrived aboard around noon, and they kept coming in all afternoon. That meant we had to move into one of the enlisted men’s compartments until we went ashore.

I took a nap in the afternoon, and when I got up and looked out, I found we were very close to shore, for we had moved up close to pick up casualties. About 6 we moved back out to where it was safe, as some shells had landed pretty close to us. The news kept coming in to us, so we knew the boys were having a much tougher time on shore than was expected.

February 21, 1945

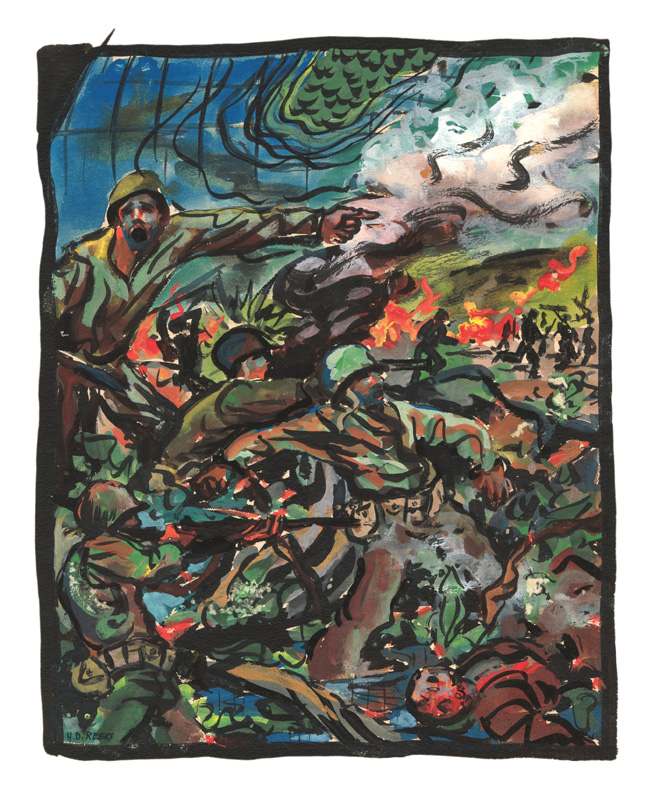

The nights have been cold, and I mean cold. Yesterday dawned dark and rainy and it was cold and damp all day, with high waves. We stayed out all day, and took in only a few casualties. We were scheduled to go ashore, but the fighting was so terrific that the Graves Registration Section was not ordered in until this morning. About 10:30 we piled into a Higgins boat and started for shore. The waves were very high, and we all started to feel woozy in our stomachs.

When we got to the control boat, we were told to go in and pick up casualties near the fuel dump, which was burning very fiercely. So we all took off our packs and rifles and stacked them in a corner of the boat.

The coxswain landed us about 150 yards from the burning dump. We ran ashore and looked around but could see no casualties. Then the coxswain got scared and shoved off with all of our packs and equipment on board.

Meanwhile, we darted from one shell hole to another on the beach. The beach was cluttered with all sorts of boats and amphtracks and other vehicles that had gotten bogged down in that awful volcanic sand, the worst stuff I have ever seen. Walking in it can be compared only to walking through a foot of new-fallen snow.

After an hour or so on the beach, we located Capt. Nutting who knew where the cemetery was supposed to be, so he led us there. I lay in a shellhole and ate my lunch out of a can of C-rations which I found in the sand. Then in the afternoon we dug our foxholes, after which I started to look around for ponchos so that every man in our outfit [the Graves Registration Section] would have a poncho that night even though we had no blankets.

February 22, 1945

Last night was plenty cold. I had on a flannel shirt, my dungaree jacket, and my field jacket, with 2 pairs of heavy socks on. We slept with our helmets and boots on. I wrapped the poncho around me like a blanket and went to sleep.

About midnight I woke up cold and started to shiver. I pulled the poncho around me closer than I had before and finally went to sleep again. About 4, I woke up and heard the sound of approaching planes and knew they were Jap planes. They came in fast from the sea right over the beach and up to the airfield and dropped their bombs right at the edge of the airfield, about 200 yards from us. That scared me so that I started to shiver again, and shivered and shook for quite a while.

Finally morning came and some of the boys built a fire and we all got around it and got warm. I spent most of the day in scouting the beach for ponchos, blankets, and shelter halves for the boys and secured almost enough blankets for all. But it also rained hard all day, and we all got soaking wet. Anyhow we went to sleep tonight with a poncho and blanket under us, and we wrapped ourselves in another blanket.

February 23, 1945

The sun came out this morning and dried things off, and it surely felt good. This morning the flag was raised over Mt. Suribachi, and we looked at it through our field glasses and thrilled at the sight.

February 24, 1945

Last night was one I shall not soon forget. We had our second air raid right after dark, and all of the hundreds of ships in the harbor fired up tracer bullets at the [enemy] planes. It was as pretty a sight as I have ever seen, and fortunately they drove the planes away.

But last night was also the night of the great artillery duel. All of our artillery was scattered along the beach, and the Japs shelled our beach all night, so that all the shells passed over our heads, going first one way and then the other. It was a steady performance all night.

This morning we also moved to another foxhole that was vacated by some boys who were moving up toward the front. It was lined with some 96 sandbags on all 4 sides, and we rigged up good shelter over it with a poncho and 2 shelter-halves, so it should be very comfortable for us.

My foxhole buddy is a young 2nd Lt. from Buffalo, Jack Greeno, who graduated from Quantico…. He is the division personal effects officer, and will have charge of sending the personal effects home to the families [of the men killed]. He’s a good egg, and we kid each other a lot. He thought I was soft at first because I was a chaplain, but I showed him I could take it, so we get along OK now.

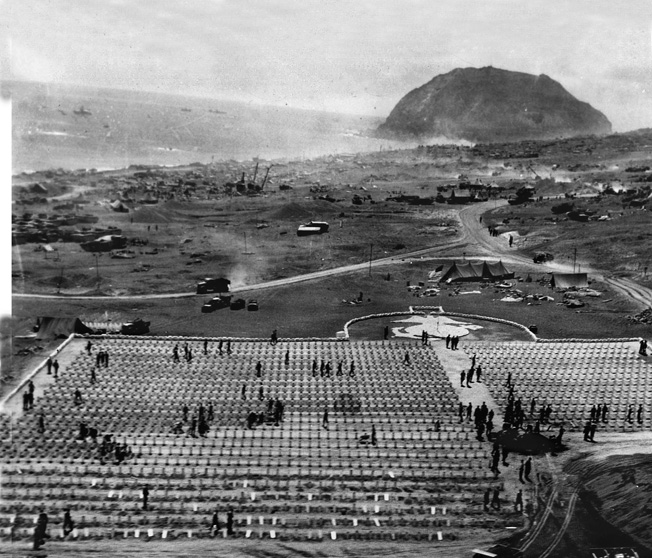

We buried the first row (50 men) in the cemetery today. Ever since we came ashore the men of our outfit have been collecting the bodies, the engineers went over the cemetery area with mine detectors, and the bulldozer has been scooping out a large trench.

When the whole row was buried, 2 of the boys went with me and placed a flag on each individual grave while I said the committal service over it. Here is what I said: “You have gallantly given your life on foreign soil in order that others might live. Now we commit your body to the ground, in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. May your soul rest in eternal peace. Amen.”

February 28, 1945

We have had mortar shells and sniper fire which have interfered tremendously with our cemetery work. A mortar shell landed right by the bulldozer in the cemetery this noon and scared us plenty, for it was only about 50 yards away.

Then this afternoon 4 of our men were carrying a body when one of them stepped on a land mine not more than 15 yards from my foxhole. It blew his leg off and injured 2 of the other boys. Then one other day one of our men was hit by a sniper as he was working among the bodies, so we have had 4 casualties among the Graves Registration Section.

March 1, 1945

This morning while walking along the beach I saw some of the men who were on our ship and learned that the transport had unloaded all its equipment on an LSM [Landing Ship, Medium] which had just come in to the beach. I went aboard and discovered my pack and typewriter. Then I went back and told the other fellows in the Graves Registration Section and we went down with a truck and recovered all our gear that had been taken back to the ship the day we came ashore. But my communion kit is still on the transport as I left it with Chaplain Vierling. Now the transport is on its way with a load of casualties to either Saipan or Guam so I won’t have my kit for quite some time.

Today the first mail was flown in to us, and I got 6 letters, which were mighty welcome.

March 2, 1945

Today [Division] Chaplain [Harry C.] Wood sent Sneary down to relieve me, and I was told I was to spend the day away from the cemetery, but after a couple of hours of visiting at the division CP and reading my mail, I felt restless and wanted to get back to my job. I told Harry that I didn’t need relief.

I guess he has his doubts as to whether I could stand it, for they told me that [since] this was my first operation, I probably wouldn’t eat for several days, that I wouldn’t sleep, that I would lose weight, that the smell of dead bodies would sicken me and make me puke, and if that wasn’t enough, the sight of the maggots and flies crawling all over the bodies would surely finish me. But I haven’t missed a meal since we hit the beach nor have I felt sick to my stomach, for I have been determined to stick it out and show them I could take it.

I conducted my first service for the men of my outfit tonight after supper. It was just a short service of scripture and prayer, but it seemed to make them all feel better, as they have been asking for a church service for several days.

March 6, 1945

Went up and visited the division hospital today. One of the doctors said that this has been the “healthiest” island that our men have ever fought on in the Pacific, in that no one has been sick and there have been no epidemics. But in the hospital they have had at least one major operation to perform every hour of the day and night, as the men have been brought in with every kind of wound in the book––and some not in the book.

March 12, 1945

Three weeks ago this morning our men hit the beach, and the island is not secure yet, for we found about twice as many men and twice as many weapons and twice as much hard fighting as we expected to face. From where we are, we can see the engineers blowing up one cave after another a mile or so away.

March 13, 1945

One of the things I shall always remember is the sight of hundreds of Marines walking through the cemetery with their heads bared looking at the grave markers to see if they can find their buddies. When they see a familiar name, they pause for a moment or kneel before the grave and say a prayer. It has been going on all day long ever since we started to put up the markers.

March 15, 1945

Let it never be said that a man becomes a chaplain for selfish reasons. Even though they pay me $300 a month, I would gladly trade it for the chance to sit in at [my son] Billy’s first birthday party tomorrow.

Today was a solemn day here. There were at least 4,000 4th Division Marines lined up around the cemetery long before the hour of dedication. They stood for many minutes in the hot sun without a sign of emotion and without saying a word to their buddies. It was as though they were in some great cathedral where every stone and every pew was sacred.

Nearly a half hour before the ceremony the general [Maj. Gen. Clifton B. Cates] arrived, and all stood at attention as he came into the cemetery. Then at last it was time for the dedication ceremony to start. It was short, far too short to pay the tribute the dead deserved.

There were the Marine Corps hymn and “Rock of Ages” played by the band, invocation by the Jewish chaplain, a few remarks by the division chaplain, the general’s remarks, and the benediction by the Catholic chaplain. Then came the solemn moment, however, when the 3-volley salute was fired, followed by the playing of “Taps.”

Then we all snapped to attention as the flag was raised above the cemetery and the National Anthem was played. It stirred all the emotions in me that had been suppressed during the strain of the last 3½ weeks, and I felt the tears trickle down my cheeks….

The cemetery looks beautiful now. 3 weeks ago it looked hopeless. We were attempting to set it up on a hillside above the beach where the soil was nothing but shifting volcanic silt. It took a bulldozer nearly 3 days to scoop out a level trench in order that the men might be laid in there. Meanwhile, the bodies piled up outside until at one time there were nearly 400 lying within 50 yards of my foxhole.

Still, life had to go on, and we ate 3 meals a day and slept at night in the midst of that stench. Eventually we got them all buried and then the bulldozers scooped the earth back into the trench and the trucks brought in real dirt and packed it down on top of the volcanic sand.

Then the markers were put up, the graves were mounded, a stone fence was placed around the cemetery and painted white, and a flagpole raised at one end with the Marine Corps emblem in white stones around the flagpole. On this side of the cemetery is a small plot where the war dogs are buried. The 3rd Division cemetery is right next to ours, but the 5th Division set theirs up on the other side of the island.

March 16, 1945

We got word that our men were just taken off the front lines this morning. Probably many men have been killed since Iwo was officially declared “secure” 2 days ago, for there has been just as desperate fighting during the last 48 hours.

It was 8 days after getting ashore before I had a chance to shave. By then I had quite a moustache, and so I decided to keep it….

March 17, 1945

We had our final committal services today, making a total of 1,800 men buried in the 4th Division cemetery. Of the officers who were on the same ship with me on the way out, we have buried at least 10. One of the men in our small fellowship group is also lying in the cemetery. It was as though he were one of the boys from my own parish, for I had grown to look upon the boys of that fellowship group as my very own.

The majority of men we buried were killed by shrapnel rather than bullets. Shrapnel has terrific force and literally tears a man to pieces, leaving gaping holes in the head or arms or legs or belly, or else tearing them off completely. Some of the men we buried were not even identifiable, as they had been so torn to pieces that there were only 15 or 20 pounds of body left and it was buried in a cardboard box.

When the bodies were first collected, I did not go any nearer to them than was necessary, but as the division wanted a count each day on the number of bodies, I was asked to count them about 4 every afternoon.

The first week it necessitated walking among row after row of unburied men who had died with the greatest possible violence, and counting them accurately. At first the only way I could do it was to hold my nose and smoke one cigarette after another. But day after day of living under such conditions soon changed that until I could walk among them with hardly a thought of how unbearable it was.

Eventually I reached the point where I could turn a dead man over, or pull things out of his pocket, or cut off his dog tag, or almost any other thing that was needed, and then, if I lifted up my hand and found it covered with a man’s guts or his brains, I calmly brushed it off in the sand, and when I got a chance later on, washed my hands with soap.

There was a team of 5 men who registered each man before he was buried. They removed all personal effects and determined the cause of death. Then the ditty bags containing the personal effects were brought to the burial officer (Lew Nutting) who went over them with his assistant (Gus Sonnenberg) and myself.

We looked them over very carefully and made an inventory of each one. Then a tag was put on the outside of the ditty bag and it was handed over to the personal effects officer (Jack Greeno). He had to pack them in a big box and when we get back to camp, he will have to go over each one carefully, and then send them to the Marine Corps Commandant in Washington.

Most of the boys had wallets and pictures of their loved ones, and it was always heartbreaking to see a picture of a wife and child, which happened again and again. Most of them wore I.D. bracelets, quite a large number a ring of some sort, a smaller number had wrist watches, then there were other things such as cigarette cases and lighters and religious medals and rosaries and New Testaments.

We had to remove “art” pictures from the wallets, and also pictures of the Marines taken with “gook” girls in Honolulu. In addition, we had to remove a large amount of more or less filthy literature that the boys carried.

Once in a while, we ran across something funny in the midst of an otherwise humorless task. For example, there was one cartoon which showed a group of Women Marines in boot camp, nude to the waist, lined up for inspection. The male officer who comes out to inspect them says: “Good grief! I said kit inspection!”

March 18, 1945

This morning we packed up our gear and filled in our foxholes and left the cemetery area to go down to the beach go aboard ship to go back to our camp at Maui. But after waiting all afternoon and evening for an LST [Landing Ship, Tank] or an LSM to go out to my ship, the Jupiter (AK-43), none came, so I had to spend my last night ashore under an overturned amphtrack on the beach with a shelter-half under me and another wrapped tightly round me.

March 19, 1945

What a thrill it was to come back on board ship after 26 days on Iwo, during which I hadn’t had my clothes off once! I stripped down and stepped into a hot shower. The sheer luxury of it was matched only by what followed: a wonderful shampoo, a nice, clean shave, and then a big dish of ice cream!

March 20, 1945

Last night I had a couple of hours of thinking it through, and it came to me that there were at least 3 ways in which I have changed since becoming a chaplain. First, until I left to come overseas, I had always felt a sense of inferiority and inadequacy in my parish work at Palmer [Massachusetts] because I felt so young and inexperienced. Now the very fact that I have come overseas, been with the Marines in combat, and in the toughest battle the Marines have ever fought, has changed all of that so that I will never have the same feeling of inferiority and inadequacy again.

In the second place, I had certain preconceived and very definite notions as to the way a minister and a minister’s wife should act in a parish. Now I can see how much wiser I would have been had I thrown overboard a lot of those ideas and used my own common sense.

In the third place, my life at Palmer was marked by the fact that my work was my master instead of my being master of it. Now I realize that I should never hold myself to such a rigid schedule of studying again, but there should be a good balance between work and play.

There is something else which has matured me even more and given me a deeper and newer kind of faith. It goes back to the sermon I preached at Chaplains School the day before I received my orders. In that sermon I spoke of Phillips Brooks, who wanted to be a teacher but who failed and became a minister instead. It was as though he wanted sea duty, I said, but got stuck with shore duty. Then the next day I got my assignment to the Marines. It was a real test for me, for I wanted shore duty and was getting stuck with Marine duty.

I resented it at first. Why should I be the only one in my class to be sent overseas directly to the Marines? But gradually I began to see that if I could make the best of it and triumph, I would never be afraid of life again, for there could never be anything worse than this which could happen to me.

The fact is, of course, that the mental agonies I suffered from the day I received my orders until we finally landed on Iwo were a great deal worse than the actual agonies of ducking into foxholes to escape sniper fire or mortar shells, worse than the terrors of the air raid the first week, worse than the smell of death that was ever present, and worse than the sights of hundreds of dead Marines.

I can say it now that I died a thousand possible deaths before ever we landing on Iwo Jima!

Chaplain Hotaling, who served in several parishes in postwar civilian life, was a retired lieutenant commander in the Chaplain Corps of the United States Naval Reserve until his death on May 16, 2010, at the age of 94, the last of the surviving Iwo Jima chaplains. Some of his experiences were included in the book, Flags of Our Fathers, by James Bradley.

Fascinating read. Eternal thanks to Ch. Hotaling and all those who served with him.

Fascinating indeed!