By Susan Zimmerman

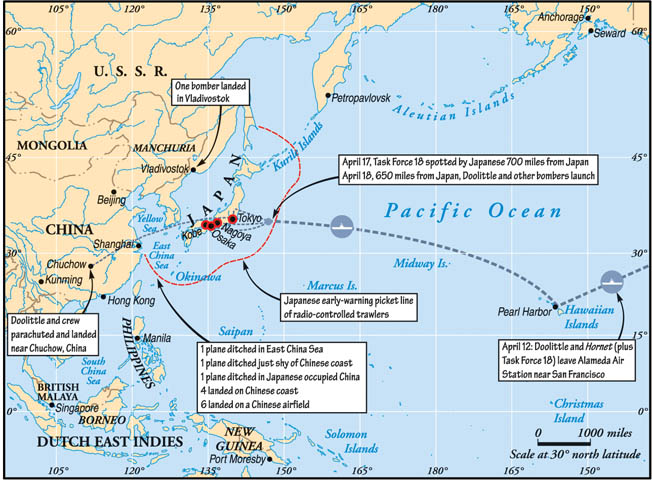

April 18, 1942, will forever live in American military glory as the date of the Jimmy Doolittle Raid on Tokyo––a gutsy, never-before-attempted combat mission to fly North American B-25 Mitchell bombers off the deck of an aircraft carrier and attack an enemy capital.

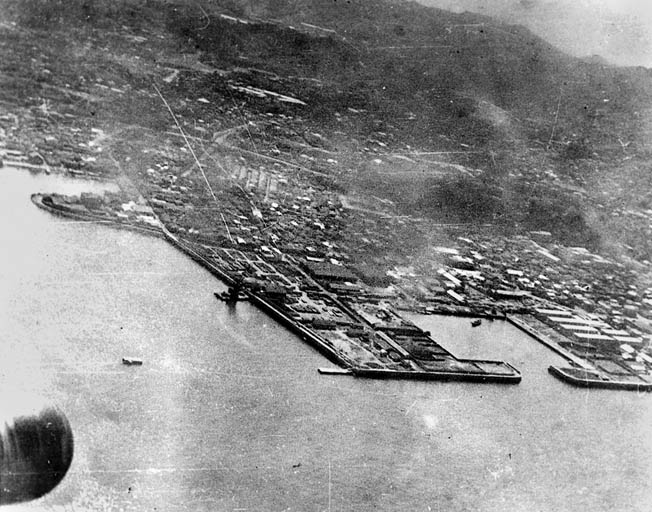

Although the damage from the bombing of Japanese targets was a blip on the screen compared to the devastation that Japan delivered to Pearl Harbor, this American retaliatory action shattered the island nation’s inscrutable veneer and reminded the Japanese that they, too, were vulnerable. Although it came so early in the war, the raid launched the beginning of the Land of the Rising Sun’s downward spiral and eventual defeat in World War II.

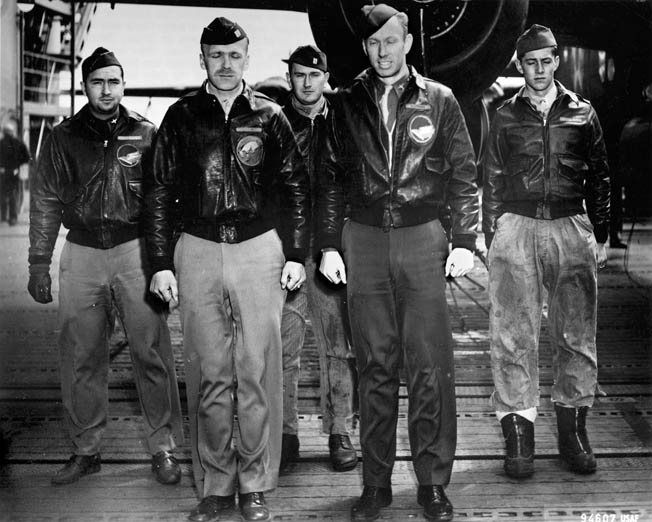

The Doolittle Raid on Tokyo was America’s first joint action with the Army Air Forces and the U.S. Navy. This groundbreaking mission shipped 16 B-25B Mitchell land-based bombers and their five-man crews aboard the aircraft carrier USS Hornet to within 500 miles of the Japanese coastline. The mission climaxed with the planes bombing Tokyo and other industrial centers. The leader of the improbable raid was the legendary aviator and World War I pilot Lt. Col. James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle.

Because the success of the raid depended entirely on the element of surprise, there was a code of silence so widespread that paper trails were often nonexistent and information cryptic. Two days after the raid, the U.S. War Department reported the mission to America but not its staging point. President Franklin Roosevelt maintained this clandestine air by coyly saying the pilots had taken off from “Shangri la,” in reference to English author James Hilton’s 1933 best-selling book, Lost Horizon. The raid began and ended in secrecy and, some 70 years later, the secrecy still flies high––the mysteries of the Jimmy Doolittle Raid remain.

The Mystery of Plane 8

The eighth plane to take off from Hornet was the only B-25 that became mired in controversy due to its inauspicious landing in Russia and the aftermath. Although all 16 of the planes were low on fuel due to the forced premature launch from the carrier, all 15 headed for China after dropping their bombs. Plane 8 broke ranks and landed in Vladivostok, Russia. An air of complicity that the landing was “ordered” has tailed the plane and crew ever since.

There were many questions that plagued Lieutenant Nolan A. Herndon, the bombardier-navigator on Plane 8 who, along with pilot Captain Edward J. “Ski” York, co-pilot Lieutenant Robert G. Emmens, and two other crewmen, was interned for 13 months in Russia after the unauthorized landing. Herndon felt that the true reason for the detour was to test Russia’s wartime allegiance and find out if their plane would be permitted to refuel and continue to China, and also to collect information about Russia’s airfield for use in possible future attacks on Japan. Herndon believed that both Emmens and York were privy to the flight’s surreptitious purpose.

While the defining document instructing Plane 8 “off course” remains elusive, there is a significant black-and-white paper trail that leads to Russia’s landing fields. The very last line in Doolittle’s February 1942 feasibility report to General “Hap” Arnold states, “Should the Russians be willing to accept delivery of 18 B-25-B airplanes, on lease lend, at Vladivostok our problems should be greatly simplified.…” Vladivostok was some 600 miles from Japan, while China’s fields were double that distance, hence Russia’s cooperation would have simplified matters.

The United States had its eye on Russian soil for the post-bombing landing as evidenced by Doolittle’s report and the Lend-Lease Program enacted on March 11, 1941, which provided billions of dollars of war matériel to the Allied nations including the Soviet Union. However, the Soviet Union wanted to keep its distance from the United States, so the mission went forward without Russia’s cooperation and the 15 courageous crews either bailed out over or crash landed in China due to low fuel, except for one.

Debriefing papers that were filed following the raid by Plane 8’s pilot, Captain York, fueled Herndon’s suspicions. York reported low fuel as his only reason for flying to the Soviet Union and also provided significant information about the airfields around Vladivostok. “In the later years of the war, 250 U.S. pilots flying B-17s from Alaska’s Aleutian Islands would seek refuge in the Soviet Union,” he wrote.

Jimmy Doolittle’s Raiders official website corroborated other events with its own repository of military reports and records from the raid. A rather incriminating disclosure revealed that Herndon once asked Doolittle about the flight to the Soviet Union and received this cryptic answer: “I’ll tell you one thing, Herndon: I didn’t send you there.” Doolittle’s rather sideways response spoke volumes. If he didn’t send him there, then did someone else? And, if so, who?

There were also skeptics within the ranks of the raiders. A 2007 Los Angeles Times article reported that Tom Casey, manager of the Doolittle Tokyo Raiders organization, called Herndon’s story a “mystery” that “military officials never would confirm or deny,” while Carroll V. Glines, the raiders’ historian who has written three books on the subject and co-wrote Doolittle’s autobiography, said, “All I know is, Nolan was there, and I wasn’t, but I could never find any clues to confirm that it happened that way.”

Although Herndon was mostly a lone voice of dissent over the years, Plane 9’s navigator, Lieutenant Thomas C. Griffin, shared his view. In notes from a 2007 roundtable discussion, Griffin recounted seeing York at a raider reunion in which “Ed was just as evasive then as he was when Davey [Jones] and I ran across him in Washington prior to the raid.” Later on, Griffin said, “I guess we will never find out if the State Department or the Secret Service set up ‘Ski’ York for a special secret mission. It is my belief that his clandestine mission instructions were never put in writing.”

Some 50 years later, Plane 8’s co-pilot, Lieutenant Robert G. Emmens, opened up about the controversial flight and the questionable conditions of his crew’s formation in a letter to a friend in 1989. “Ours was sort of a bastard crew made up of guys left over at Eglin [Air Force Base, Florida] flying on the B-25 that was a last-minute substitute for the one that bellied in the last day of training at Eglin. We formed as a crew after all the rest of the planes had left Eglin for the West Coast. We had never flown together before and had never made a practice take-off before the real one we made off the Hornet.”

Emmens’s admission that Plane 8’s crew formed at the 11th hour leaves the door wide open for speculation as to why this plane was ever called into action. There were 24 crews (though only 16 would fly the mission) that spent three weeks at Eglin training and honing the critical carrier take-off skills––except for Plane 8’s crew. All the planes had their carburetors carefully adjusted at Eglin to fly the 2,000-mile mission without refueling––except for Plane 8. So, why were an untrained crew and unadjusted plane called into service when there were already modified planes and trained crews at the ready?

Maybe someday those instructions for Plane 8’s “AWOL” flight will surface, which might also explain why York and Emmens just happened to start speaking fluent Russian when the plane touched down in Vladivostok. Until those papers surface, however, the true story of Plane 8 remains up in the air.

The Mystery of the Long Beach Flight

A secret B-25 flight from Long Beach, California, to Gary, Indiana, that tested the bomber’s maximum range was then—and still is—completely off the radar screen. In January 1942, when the top-secret raid was on the planning table, it remained to be seen if a land-based bomber could take off from an aircraft carrier and go the distance. On February 2, 1942, the well-known Norfolk, Virginia, test flight off the Hornet proved that the B-25s could get in the air. Then, sometime later that month, the distance was put to the test with the mysterious Long Beach flight.

The only known story about this flight appeared 61 years later in the Fall 2003 (September) publication of the Jimmy Doolittle Air & Space Museum Foundation NEWS at Travis Air Force Base in California. In Fernando Silva’s article, “Behind the Scenes of the Doolittle Raid,” he explains that in February 1942 his father’s crew (separate from Doolittle’s men and planes) was instructed to fly a B-25 “configured to carry a dummy bomb load of 2,000 pounds” from the Long Beach Airport (then a USAAF Air Transport Command Base) to Gary, Indiana, near Chicago, while another crew flew a separate mission to Canada.

According to Silva’s article, the flight’s purpose was “to determine the maximum range that could be squeezed from every drop of gas by setting the correct throttle, prop pitch and mixing the controls … raw data was then turned over to North American Aviation’s engineers.” Since the B-25s used in the raid were manufactured in Inglewood, California, about 15 miles from Long Beach, that would have given the test flight access to an unmodified B-25 for the 1,700-mile flight to Gary, which approximated the raid’s greatest distance.

The cloak of secrecy surrounding the mission kept many events in the dark, especially this maximum range test that called for a “fly through the Grand Canyon and as close to its walls as possible,” then to “fly at tree-top level all the way to the steel mills of Gary, Indiana.” Although there are no known witnesses to the canyon’s fly-through in 1942, historian Mike Anderson, who has worked in the canyon for the past 20 years, has seen military jets fly through the inner gorge, which puts them as close to the walls as possible.

America’s grand geographical icon is no stranger to the military. In an October 3, 1920, memo, Lieutenant Harry Halverson detailed his photographic military flight over the canyon to Major Henry “Hap” Arnold. Some 20 years later, Arnold and Halverson would both coordinate missions in conjunction with Roosevelt’s order to come up with a retaliatory raid following Pearl Harbor. Arnold would be involved in the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo while Halverson would direct his namesake project (aka HALPRO), a series of land-based attacks from China (which were rerouted and bombed the oil facilities at Ploesti, Romania).

Colonel Charles R. Greening, pilot of the 11th plane to launch from Hornet, made reference to preraid tests in his official report, “The First Joint Action, A Historical Account of the Doolittle Tokyo Raid––April 18, 1942,” submitted to the Armed Forces Staff College in December 1948. Greening wrote, “Certain preliminary tests had been accomplished with the B-25 prior to the time personnel had been ordered to Eglin. Takeoffs had been accomplished from a carrier in the Norfolk area … and preliminary gas tests had been made to determine how far the airplane could travel with a given amount of gasoline and still allow for a reasonable weight of bombs.”

After the Silva story appeared in the Doolittle Air & Space Museum Foundation NEWS on November 7, 2003, Carroll V. Glines wrote to the museum’s historian questioning the article’s validity. “As [the raiders’] historian, I am distressed about the story in the newsletter written by a Mr. Fernando Silva concerning test flights he alleges were made in February 1942 from California to Gary, Indiana, and Canada. There is absolutely no truth to this story and I’m very disappointed that it was published without checking with me. If he insists the story is true, I’d very much [like] him [to] produce some documentation to back it up.”

The museum’s publication never issued a retraction on the story, but four months later, in the Spring 2004 (March) publication of the NEWS, Glines authored his story that covered 17 “Myths and Facts about General Doolittle and the Tokyo Raid.” For the sixth item, he wrote it was a myth that “B-25 aircraft were dispatched on secret flights from California before the Raid to determine if B-25s could fly the distance required from the carrier to the destination airfield in China.”

The “facts,” according to Glines, were, “No such long-range test flights took place. All arrangements were top secret. The aircraft were flown from Pendleton, Oregon, to Columbia, South Carolina. The B-25s were modified en route by the addition of fuel tanks in the bomb bays and crawlways of each aircraft; none of this work was performed in California. The B-25 could not have flown the distance required if these extra tanks had not been installed.” There are two sides to every story.

The mystery of the Long Beach flight knows no bounds. In 2010, the staff at the Doolittle Museum at Travis Air Force Base, northeast of San Francisco, California, claimed that no contact information for Fernando Silva existed. In 2011, the museum’s historian, Mark Wilderman, researched this matter and reported, “I went to the Travis Heritage Center Library to find the original paper copy of the Jimmy Doolittle Air and Space Museum News…. Neither the web or hardcopy versions had any information about the author … other than his name and the facts presented.”

Wilderman further explained, ”I also checked the entire issue of the NEWS from cover to cover … and found none. There is no original manuscript of Mr. Silva’s article on file at the library to obtain a mailing address or phone number. I also checked the next NEWS edition and likewise found no mention of Mr. Silva or acknowledgement for submitting a rather good article…. I regret to say I have hit a dead end in my search for Mr. Silva’s contact information.”

Just like the eighth plane, the California flight’s paper trail lies scattered to the wind. The fact that to date both the Silva and Glines stories remain on the museum’s website reflects the depth of the ongoing secrecy surrounding the mission.

The Mystery at Sacremento Air Depot

The last week of March 1942 was fraught with intrigue at Sacramento Air Depot where the B-25s underwent their final modifications before being loaded aboard the Japan-bound Hornet. During this time there was a flurry of “priority,” “extra priority,” and “confidential” teletypes and phone calls that sent the Sacramento personnel scrambling to follow unusual orders and track down critical missing equipment, no questions asked. According to a March 26 teletype sent to Sacramento, Colonel Doolittle was “to be given the highest priority without explanation.”

Because no one at Sacramento knew the critical purpose of the work, the request for four 500-pound practice bombs took three different officers at three different bases over two hours to decipher and sort out. Unbekownst to everyone, the bombs were needed to test that the plane’s bomb release mechanism still functioned after the fuel tanks were reinstalled.

The following verbatim telephone dialogue between a Major Urbani at Sacramento Air Depot and a Major Cotton at Hamilton Air Force Base, which has never before been published, begins March 27, 1942, at 12:05 pm:

Urbani: I am trying to find a 500-pound practice bomb.

Cotton: A 500-pound practice bomb?

Urbani: Do you have anything over there like that?

Cotton: There is a bomb sitting over at the end of the ordnance warehouse that looks about like that. I can contact ordnance on the telephone and let you know.

Urbani: How about calling me back?

Cotton: They may be out to lunch, but I will call you back in an hour or so.

Urbani: We have to get this bomb right away. It is for the Doolittle Project and they are not going to be here very long.

Cotton: If I can find one I will call you right back, and if I cannot find somebody who knows what it is all about, I will get them right after lunch.

Urbani: All right. Thanks.

About 20 minutes later, Major Urbani made a call to another air force base for the needed bombs. It was 12:28 pm when Urbani explained to a Colonel Kenzie in San Francisco that the Doolittle flight needed some practice bombs “as sort of a dummy or to try out something.…”

Urbani: I am after four 500-pound practice bombs. At least four if I can get them. They are for the Doolittle flight. They have to use them up here as sort of a dummy or something to try out something. Can you tell me where I can get them?

Kenzie: Where do you want them?

Urbani: I want them up here at the field.

Kenzie: Up there at the field and you want four of them?

Urbani: Yes, sir.

Kenzie: I will ship them in there just as soon as I can. I will call you back and tell you when they will get there.

Urbani: They will have to be here this afternoon if they are going to be any good to us.

Kenzie: We will get them there if it is at all possible.

Urbani: All right, sir, thank you very much.

Kenzie: I will call you back and let you know what is going on

Urbani: Thank you, sir.

About 10 minutes later, at 12:40 pm, Kenzie called back and spoke to Urbani’s secretary.

Kenzie: I just talked to Major Urbani about these bombs. Do you know what he is talking about?

Secretary: He was asking for four bombs for Colonel Doolittle’s flight.

Kenzie: What kind of bombs did he want?

Secretary: He wanted 500-pound bombs so that they could be emptied and filled with sand to make up the weight. That is all the information I can give you on those.

Kenzie: Will you leave this note for him?

Secretary: All right, sir.

Kenzie: We do not have any 500-pound practice bombs, but we have 100-pound practice bombs at the Sacramento Municipal. We have 500-pound demolition bombs, which you could take without the fuse for the 500-pound weight. Would you ask him to call me as soon as he gets back?

Secretary: He will be back in a few minutes and I will have him call you right back.

Kenzie: I will wait [for] lunch until he calls.

Secretary: Thank you.

About one and a half hours later, at 2:01 pm, Urbani called and made arrangements with Kenzie to retrieve the training bombs located at Hamilton. Then Kenzie suggested using the demolition bombs without fuses or drill bombs since practice bombs get dropped from the air and a drill bomb stays on the ground:

Urbani: On those bombs, I found two training bombs at Hamilton Field Ordnance. They said I would have to go through you to get them.

Kenzie: We can get them for you, but here is the thing––how about using those 500-pound demolition bombs at Sacramento? Take them without fuses.

Urbani: Without fuses? I do not know. This is for Colonel Doolittle’s job and they wanted the 500-pound practice bomb.

Kenzie: We do not have any practice bombs.

Urbani: They said something about the old type and the new type; I could not quite gather it all. They said that there were two different types of bombs.

Kenzie: We do not have any 500-pound practice bombs.

Urbani: Those demolition bombs must be down at the Municipal [Airport], is that right?

Kenzie: Yes, they are right here at hand.

Urbani: All right. I will tell them about that. There are two practice bombs at Hamilton Field, and if they want them, we will have to get an OK from you. He will let you know later on it.

Kenzie: I do not know about these practice bombs being over there; we have no record of that, but we have what we call a drill bomb.

Urbani: That is it, a drill bomb.

Kenzie: There is a difference in those. The practice bomb is the one that we take up and drop from the air, and the drill bomb is strictly a ground bomb to practice loading and unloading.

Urbani: All right. I will tell them about those demolition bombs and use them without the fuses. They will weigh pretty close to 500, will they not?

After it finally came to light some 45 minutes later that Doolittle wanted the bombs for size and shape, Urbani opted for the drill bombs. It was 2:45 pm when Urbani called Kenzie once again.

Urbani: We will have to borrow those two bombs down there, the drill bombs, if we can get them. If you will have them released, I will send a truck over there right away.

Kenzie: We can get them to you much faster by just putting them on a truck and sending them up.

Urbani: That will be fine. Then we can give them a load of supplies going back. Will you see that he gets off this afternoon?

Kenzie: I will have them contact you when they arrive at the field.

Urbani: I will leave word here in case I am gone, so they will watch for him. Thank you, sir.

Urbani’s conversation was symptomatic of the “no-questions-asked” orders that delayed getting the job done. He was completely in the dark that the success of the raid required a properly functioning bomb-release mechanism.

The Mystery of Jurika’s Dossier

The 32-year-old flight deck and intelligence officer aboard Hornet who prepared the raiders for their day of reckoning with Japan was Lieutenant Stephen Jurika, Jr. His two-week crash course was pivotal to the success of the raid. As the carrier sailed across the Pacific, Jurika briefed the crews on their flight routes, Japanese targets, the country’s history, politics, and even psychology.

Jurika was made to order for the mission. He came aboard with an extraordinary dossier on Japan. In just under three years he served as a naval attaché in Japan, then in the Office of Naval Intelligence, and finally aboard Hornet. His military service reads like an open book, but Jurika’s own dossier makes for some interesting reading.

In June 1939, when the Philippine-raised Jurika took up the position of naval attaché in Japan, espionage came with the job. According to retired Colonel John F. Proute, “These officers performed a number of protocol functions, but everyone knew that their primary mission was to obtain intelligence concerning the military forces of the countries in which they served.” In the 2003 book Doolittle, Aerospace Visionary, author Dik A. Daso wrote that Jurika said, “I spent most of my time locating and pinpointing industries, industrial areas, and all manner of bomb target information.”

The vast amount of classified information Jurika gathered about Japan came from his tenure as naval attaché there, which ended in August 1941. He even candidly detailed his covert work in an October 27, 1940, letter to his father-in-law, Colonel Harry Smith. “Since this is going in the diplomatic pouch, I shall tell you a bit of what I’ve been doing. For the past four months I’ve been drawing up bombing maps of Japan, by main manufacturing, districts, a job which has never been done in this office.”

Jurika went on to explain that he was involved with making “plans for bombing Tokyo, its powder factories, munitions factories, government buildings; collecting and evaluating information of Japanese bases in South China, Indo China, the South Seas and getting down to business on every phase of the possible war. As a result, the Naval Attaché has requested that I be sent, for war station, to the Staff of Commander Aircraft, Battle Force as an assistant operations officer.…”

For a nation not at war, Jurika’s work seemed to indicate otherwise. On September 1, 1939, Roosevelt had promised to stay neutral, but nine months after Germany invaded Poland, Jurika was drawing up bombing plans. At the end of his attaché duty in August 1941, Jurika went to work until October 1941 in the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), where he provided the information he had gathered and reported about Japan’s new Mitsubishi Zero high-performance fighter. “Jurika had been a spy in the most traditional sense of the word, and now his experiences were being put to military use,” writes Daso.

Immediately following Jurika’s three months with the ONI, in October 1941, two months before Pearl Harbor was attacked, he was assigned to Hornet as the ship’s flight deck and intelligence officer. Then, some two months later, in mid-January 1942, he was consulting with Captain Duncan, the air officer on Admiral Ernest King’s staff, about launching a bombing raid against Japan. Two months later, in March 1942, he was briefing the Doolittle Raiders.

Jurika’s military service seemed to be on a stealth-directed course. In his October 27 letter, over a year before Pearl Harbor was bombed, Jurika had changed his wife’s booking from December 12 on the President Cleveland to November 24 on the President Taft because the State Department wanted all wives and dependents to leave Japan. In that letter he also mentioned getting the furniture and silver packed for shipping on the Yawata Maru sailing on November 13.

Jurika’s movements were noticed by Mrs. Teresea Kroll de Rivera Schreiber, wife of Peru’s ambassador to Japan, Ricardo Rivera Schreiber, though it came to light some 50 years later during an interview in London on July 23, 1997. A small, enigmatic notation in the margin of the transcript alluded to Jurika’s serendipitous departure from Japan: “How and when, then, did Lt. Cmdr. Stephen Jurika, USN, Assistant Naval attaché at the Tokyo Embassy, and soon after Intelligence officer aboard the USS Hornet, briefing the pilots of the Doolittle Raid on the latest AA and searchlight positions in Tokyo, get out so timely?”

The interview’s transcript says, “Mrs. Rivera Schreiber names her husband’s Japanese informers probably for the first time. She kept silent for over 50 years, fearing very possible retaliations against those people in a society still harboring many diehards.” The Schreiber incident, which was one of the many Pearl Harbor conspiracy theories that have surfaced over the past 70 years, happened in January 1941 when Ambassador Schreiber informed America’s ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew, about talk of a Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Jurika arranged for his wife to leave Japan over a year before Pearl Harbor was bombed, while the Schreibers, along with Ambassador Grew and other diplomats, didn’t have such fortuitous timing. After the Doolittle Raid, the Schreibers were put under house arrest; they were finally evacuated from Japan in June 1942 aboard the Asama Maru. If not for the State Department’s orders, Jurika’s wife might have been in the same boat with the other diplomats, which is why Schreiber wondered “how and when” Jurika got notice.

Jurika’s personal background sheds light on another perspective of his path to playing such a pivotal role in the raid. According to a June 1945 interview in the Miami News, when asked how he came to be assigned the intelligence role for the mission, Jurika answered, “It wasn’t my fault. I was only six months old,” then explained how his family had resided for years in Zamboanga, the Philippines, while spending two to three months each year in Japan.

Jurika’s childhood laid the foundation for his Japanese dossier. His mother, Blanche Walker Jurika, was from California, while his father, Stefan, was a naturalized American citizen originally from Czechoslovakia who started a trading company in 1902 on the Philippine island of Jolo, then moved to Zamboanga. Jurika was born in Los Angeles but grew up in the Philippines and attended schools in the islands, and also in Japan and China.

The Miami News also reported that, “[Jurika] knew Tokyo like a book and its landmarks, principal industries, buildings and vital points were all photographed in his mind.” The story also noted that he was eager to return to duty. “‘I asked to be sent back out to the Pacific a month ago. That is my job. That is where I have to go.’ His eyes show that he was thinking of Mrs. Blanche Jurika, his 60-year-old gray-haired mother, whom he had not seen since 1941.”

“‘She is a hostage,’ he continued. ‘They have moved her to a more northern island. They have a special reason. She has two sons and a son-in-law who are making things plenty tough for the Japs and are going to keep on making it tougher.’ Steve was referring to his brother Maj. Tom Jurika who has fought and killed hundreds of Japanese on Bataan and to Comdr. R. Parsons, his brother-in-law.”

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, Jurika’s mother, his sister Katsy (short for Katrushka), and her husband, Commander R. Parsons (aka Chick Parsons), were all involved in gathering information on Japanese activities. While Parsons used his Panamanian diplomatic status to get his family back to the United States in June 1942, Blanche Jurika, who remained behind in Manila to work clandestinely with the resistance, was eventually executed by the Japanese.

There is no mystery why Jurika became one of the heroes in getting the Doolittle Raid off the ground, but why he was drawing up bombing plans a year and a half before Pearl Harbor was attacked, and why the State Department wanted all wives and dependents out of Japan 14 months before Pearl Harbor, opens the door for questions.

It takes time for secrets to surface and even longer for them to be answered. Some 70 years later, Jimmy Doolittle’s Raid on Tokyo still mystifies.

When reported in the USA said all bombers made it out safely.

Hello, Interesting article, but you failed to mention that the surviving bombers were intended to go to Gen Chennault, and the American Volunteer Group, the original Flying Tigers. Chennault was also kept in the dark due to the secrecy. He always said he could have prepared possible airfield a where the bombers could have been directed to, and been used against the Japanese to much greater effect than the military “pinprick” that resulted from the mission. There can be no doubt of the morale value, but one could argue that the bombers would have also had a morale boost by the damage they could have caused the Japanese. The AVG had no bombers themselves. I had understood that the original mission to deliver those bombers to Chennault got the “side mission” to hit Tokyo, as kind of a buy one/get one ‘free’ idea. The AVG constantly struggled to keep supplied with planes and materiel. They could have brought even greater destruction to the Japanese with those needlessly lost planes, beyond the 297 credited Japanese planes destroyed in their 6-7 months of combat, before July 1942, when they disbanded and the CATF took their place, eventually growing into the 14th Air Force, also commanded by Chennault. Two sides to the coin I guess. Regards

Thank you for a well written and presented article. I thought I knew the story of the Doolittle Raid but I realize that I hadn’t read anything new about it for a long time. I am grateful that the author has used primary source documents to sharpen the focus of the questions that remain unanswered to this day. I did not at all realize that so many mysteries still exist about this operation.

I read somewhere, but don’t recall the source, that there are still many documents from the war that remain in storage and not never been examined since the war. Many of them are German documents pertaining to mundane aspects of the day to day aspects of governmental administration and it is believed that they do not contain anything significant, no big surprises. I doubt there could be much unexamined documentation pertaining to aspects of the Pacific war like the Doolittle Raid. I do believe that Classified documents still remain from the Pacific War. I hope to live long enough to learn if this is so.

You are quite correct. In addition, there are many other American WW II documents that are still classified. Since they are of no military use, the only conclusion that can be drawn is that their declassification would give lie to some of the heroic myths that were put forward to the public as well as covering some of the more egregious blunders. As having an interest in history, both by education and avocation, I am always disturbed by attempts to alter the facts. If history is to teach us anything to prepare for the future, it should be accurate, warts and all.

The wingspan of a B-24 is 110 feet. The wingspan of a B-25 is 68 feet. There is a 42-foot difference in width between the two bombers. The wingtip of each B-25 cleared the island of CV8 by 6 feet. There wasn’t enough room on CV2 for the significantly larger B-24, not even close.

Further, during the test flights of the B-25s on February 2, 1942, on CV8, it was found that the safest point to start a takeoff roll was at the rear of the island – 465 feet from the front to the flight deck. That length was picked because one of the B-25s on the test took off at the rear of the flight deck and became airborne before reaching the island. To avoid hitting a part of the island the pilot had to push the aircraft down. Out of prudent caution, all sixteen B-25s started the takeoff roll at the same spot, 465 feet from the front.

Before signing off on the mission, both the Navy and the USAAF carefully looked at all the options independently (aircraft and carriers) and both services arrived at the same aircraft for the mission – B-25B.

I have questions for any Doolittle Raid expert.

Nowhere in my readings have I ever seen any mention of flying the Doolittle raid off of a Lexington Class CV. The greater flight deck length would have allowed launching with a heavier fuel load. The greater deck width may also have allowed for 24 B-25s instead of the actual 16. Second question given the Japanese picket discovery of and broadcast of the task force location, was an immediate launch necessary? I surmise the task force could have approached Japan at battle speed for 2 hours before launching without their getting in range of a land based air strike. A carrier air strike might have been a risk, but within acceptable military odds. Lastly a comment, I think Halsey was wrong in not sending radio confirmation of the launch to China as he was under orders to do. His excuse that the IJN would know where he was makes me consider John Wayne’s line to Carrol O’Conner in “In Harms Way”, “Don’t you think the Japanese already know where we are?”

Lawrence Paul Lopresti

326 Tenth Street

West Easton, PA 18042

610-253-7552

cell 610-392-8046

lplopresti@enter.net