By Dorothy Brotherton

As John Wesley Pointon jumped into the cold English Channel water with the Royal Canadian 7th Brigade Signal Corps and struggled with a heavy radio strapped to his back toward the beach that was being torn apart by shot and shell, the farm boy from Saskatchewan tried to make his mind go blank.

He wanted to stop his brain from recording the sights around him as friends fell and men’s limbs were blown into the air. But the images of D-Day streamed into his mind and deposited their carnage forever, even as he gained the shore and pushed across the devastation of Juno Beach.

In front and beside him, the scene was a nightmare from which he could not wake. Besides noise the likes of which he had never experienced before, the sights were also worse than anything he had ever imagined. The beach was erupting in fiery, violent explosions, tanks were aflame, and men were going down, screaming, or being blasted to pieces. Behind him landing craft were burning or exploding. Wounded men lay bleeding on the sand, imploring him—or anyone—to help them.

The hellish reality at Normandy was a far cry from John Pointon’s halcyon growing-up days on his dad’s homestead at Major, Saskatchewan, near Regina, and an equally far cry from the pleasant scenes of the Okanagan Valley in British Columbia, where he would live out his senior years after a simple career driving a taxi.

In his elderly years, with the help of a cane, John would climb onto a bus to go for a bit of shopping or to join friends for coffee. He was a regular at church. He lived with his daughter’s family. He was a quiet man who never thought of himself as a hero. More than half a century after D-Day, he agreed reluctantly to sit down with a journalist, but he didn’t really want to talk about his war experience. It was still too painful.

Slowly, though, pieces of Pointon’s story came out. Hunkered down with his radio on French soil on June 6, 1944, the young man in his 20s had fallen into a protective daze. He had a hard time remembering why he had signed up back in Regina. It had something to do with being unable to find a job, the same reason behind many young men signing up for war.

The war opened up plenty of jobs for Depression-ravaged Canadians, just as it did in the United States, although few volunteers had any real concept of what they were getting into. The political reasons were somewhat vague, but the allegiance to freedom was clear and strong in young Canadians.

Before the war, Pointon had left the family farm, which his brothers capably managed. He thought it was time to seek his livelihood elsewhere, but all he could find was meager farm labor and a stint delivering meat by bicycle.

When he turned 18, Pointon tried to join the Canadian Army, but at only five feet, five inches tall, he needed two more inches to qualify to be a soldier. Pointon remembered, “I heard that the Signal Corps would take you if you were four feet tall as long as you had brains in your head.”

So he joined the #12 District Depot Royal Canadian Corps Signals. With the urgency of being shipped off to active duty upon him like many of his generation, Pointon married his girlfriend of the time in a hurry (a marriage that later fell apart). Just a couple of months after the wedding, he began military training in Regina. It simply seemed to be his destiny.

Pointon certainly had no idea he would one day take part in one of the most telling battles of history, the pivot of World War II, a battle in which Canadian forces acquitted themselves with true heroism, the invasion of Normandy.

Alone among North and South American nations, Canada had been part of the war effort from the beginning in 1939. Prime Minister William Mackenzie King had said, “There has not been a time when countries of the world have faced such a crisis as they face today. If this conqueror [Hitler], by his methods of force, violence and terror, and other ruthless iniquities, is able to crush the people of Europe … there will be in time no freedom on this continent. Life will not be worth living.”

During World War I, Canadian troops had fought admirably but had done so under the British flag and British command. Then a historical first happened. On September 10, 1939, Canada, now a nation responsible for her own actions, made her own declaration of war. It was still 27 months before Japan’s December 7, 1941, bombing of Pearl Harbor brought the United States actively into the war.

Hitler was galloping across Europe, crushing Poland, Denmark, Norway, Holland, Belgium, and France. Germany became “master of the entire west coast of Europe from Spain to the Arctic Circle,” according to historian George Brown.

Back in Regina, a frustrated Pointon studied Morse code and wireless technology wondering if he’d ever get to use them, and impatient to be on the battlefield.

“In 1939 the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals was in desperate need of young men,” says the Canadian Heritage Information Network. The recruits learned on wireless sets manufactured by Northern Electric in 1937, which had little output power and were difficult to tune. That was all that was available to the Canadian signalmen at the start of World War II.

But the better wireless set, #19, built in Canada throughout the war, formed the backbone of the Canadian Army’s field communications network with its ability to send Morse code over approximately 18 miles and voice about half that distance.

Meanwhile, in Europe disaster followed disaster for the Allies in the early years of the war. There were the dark days of Dunkirk; the plucky British managed to rescue 300,000 men in thousands of tiny boats, bringing them back across the Channel after a disheartening defeat. Then Romania and Greece fell.

Canada’s leaders saw that if Britain lost control of the seas, then Iceland, Greenland, and Africa’s west coast would become stepping stones for Germany to launch an invasion of the Western Hemisphere. Hitler’s fantastic dream of dominating the world now seemed ominously possible.

On August 19, 1942, the Allies threw themselves at the French port city of Dieppe in a surprise attack, but the raid was poorly planned and German coastal defenses were tougher than anyone had judged. Among the 5,000 Canadians at Dieppe, 3,350 became casualties.

Strategy was thereafter shaped more carefully in Ottawa, Washington, and London. It was agreed that another European front was needed. After months of secret plans, Operation Overlord, the massive invasion of northern France, dawned on June 6, 1944. From the English Channel fog emerged ships to land troops on the beaches of Normandy. Air power paved the way.

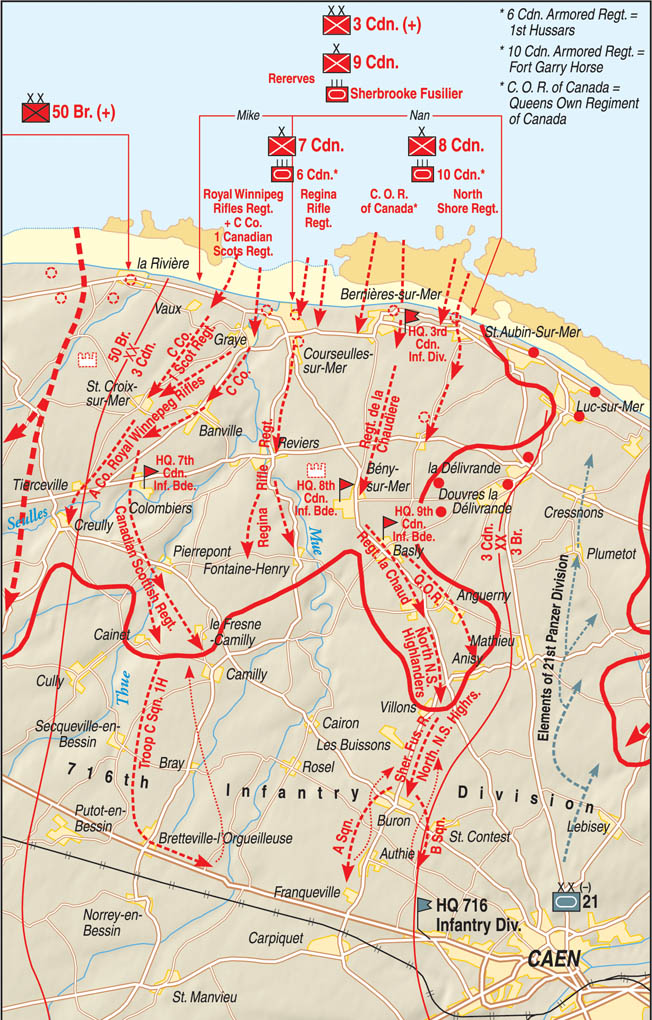

The D-Day Invasion Plan

The Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force had been established on February 12, 1944, under General Dwight Eisenhower. The initial plan produced by the Allies outlined an assault on the Normandy coast to secure “as a base for future operations a lodgement area,” says a report from Veterans of the United Kingdom.

Troops would cross the Channel under cover of darkness in a great naval armada and drop anchor in front of the 50 miles of five designated invasion beaches. From west to east, they were codenamed Utah, Omaha, Gold, June, and Sword, and they were strewn with steel and concrete fortifications, machine-gun nests, mortar pits, heavy gun blockhouses, and a maze of mines and anti-invasion obstacles. Three Allied airborne divisions would drop to secure the flanks of the invasion.

Military brass had assigned a major role to Canada. The Americans were to go after Utah and Omaha Beaches in the west, and the British could handle Gold and Sword Beaches. Between Gold and Sword was Juno, the Canadian objective.

The plan was for Canada to land 14,000 soldiers onto Juno Beach and to drop another 1,000 behind enemy lines by parachute or glider. The Royal Canadian Navy supplied ships and about 10,000 sailors, and the Royal Canadian Air Force Avro Lancaster bombers and Supermarine Spitfires supported the effort.

The Juno Beach force was part of Britain’s Second Army, under command of British Lt. Gen. Sir Miles Dempsey. The Canadian assault forces were the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Rodney F.L. Keller, and the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade, with Brigadier R.A. Wyman in charge. After heavy air and naval bombardment, troops were to land, and after the beachhead was established follow-up troops would land and move inland. The hope was that by the end of the day the cities of Caen and Bayeux would be captured and the beachheads consolidated.

Major General Keller, in command of the 3rd Canadian Division from September 1942 through August 1944, was not a popular officer. Graduating from the Royal Military College in 1920, Keller served in the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, one of Canada’s three regular infantry regiments, until the outbreak of war.

Keller went overseas in 1939 as a brigade major and became a brigadier in 1941, taking over the 3rd Division the next year. Although the troops admired Keller’s tough-talking demeanour, his staff officers were not happy with his hard drinking and cavalier attitude toward security. He had also taken a married mistress, and some felt his visits to her left the general staff officers to run the division in his absence a little too often.

Despite these disadvantages, the Canadians would do themselves proud and accomplish their mission.

Preparation for Invasion

Preparation had been going on for months with assembling and training in southern England; at the same time, a plan unfolded to deceive the enemy into thinking the main attack would be at the Pas de Calais, not Normandy. A plan called Operation Fortitude used Hollywood-style mockups of bases, inflatable rubber tanks, fake aircraft, and phony radio traffic to cause the enemy to believe the invasion would happen across the narrowest part of the English Channel at Calais. Other preparations involved aerial reconnaissance and bombing the French railways to damage German supply lines.

Weather assumed the role of a starring character in this theater of war. The invasion was first planned for May 31, but the weather was the worst it had been in the springtime in 20 years. So the operation was reset for June 5, a date that would have good moonlight for the parachute troops, halfway rising tides to help landing vessels avoid beach obstacles, and plenty of daylight.

Weather, of course, is notoriously unpredictable. As troops assembled and waited tensely on British shores and the vessels from eight navies and merchant fleets gathered off the coast, the weather deteriorated. Clearly, a June 5 attack had to be postponed. But if weather pushed the invasion past June 7, the Allies would have to wait two weeks until the necessary combination of conditions occurred again. That delay would give German troops time to strengthen coastal defenses even more and risked leaking the secret elements of the plan.

The storm was bad during the night of June 4 and all day June 5, but weather forecasters promised it would be a little better on June 6. The decision was made. June 6 would be a go.

The Five-Pronged Invasion

Shortly before midnight on June 6, hundreds of transport planes carrying paratroopers and tow planes pulling the first wave of gliders took off from their bases in England. Shortly thereafter, the naval armada left various ports and headed toward Normandy.

The magnitude of the Allied forces deployed on D-Day was truly impressive. Making up the aerial assault were 11,680 aircraft, including 4,370 bombers, 4,190 fighters and fighter-bombers, 1,360 transport planes, and 1,760 other aircraft. In the invasion fleet were 6,939 vessels, including 1,213 warships, 4,126 transport vessels, and 1,600 support vessels. The number of Allied troops that were headed toward Normandy included 130,000 troops landed via ship and 19,000 airborne troops coming with parachutes and gliders.

Keller’s 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, reinforced by the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade, would land in two brigade groups: the 7th Brigade (of which John Pointon was a part) made up of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, Regina Rifles, and Canadian Scottish Regiments, and the 8th Brigade was made up of the North Shore Regiment, Queen’s Own Rifles, and Le Regiment de la Chaudiere.

Each brigade had three infantry battalions and was supported by an armored regiment, two field artillery regiments, combat engineer companies, and extra units such as the Armoured Vehicles, Royal Engineers. The Fort Garry Horse’s tanks supported the 7th Brigade on the left and the 1st Hussars’ tanks supported on the right.

The 9th Brigade, made up of the Highland Light Infantry, the North Nova Scotia Highlanders, and the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders Regiments was scheduled to land later in the morning and push through the leading brigades. The Sherbrooke Fusiliers would provide the 9th Brigade with tank support.

Escorting the Canadian contingent across the Channel were the armed merchant cruisers HMCS Prince Henry and HMCS Prince David, accompanied by the destroyers HMCS Algonquin and HMCS Sioux.

At 3:30 am in the middle of the English Channel, the Canadian soldiers on board ship were served breakfast. The CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Company) reported that on one ship the men ate scrambled eggs, bacon, coffee, bread, and jam. Then they waited.

Some men tried to read as their ships plowed forward. On one ship, men of the 3rd Canadian Division held an amateur night with recitations, jigs, reels, and singing. On another, Dublin-born journalist Cornelius Ryan reported that in a convoy, on a landing craft where nearly everyone was seasick, Canadian Captain James Douglas Gilan “brought out the one volume which made sense this night. To quiet his own nerves and those of a brother officer, he opened to the Twenty-third Psalm and read aloud, ‘The Lord is my Shepherd; I shall not want….’”

Meanwhile, the British 6th Airborne Division (including the 1,000-man 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion) had dropped paratroopers and landed gliders northeast of Caen to seize bridges over the River Orne and Caen Canal and take a four-gun battery at Merville. Simultaneously, two American airborne divisions landed in marshy terrain behind Utah Beach to grab bridges and road junctions to delay German counterattacks and pave the way for the Allied advance.

At that point the German forces went on full alert, but the highest military authorities, including Hitler, apparently were still convinced for days to come that these landings were a diversionary tactic and that the main attack would come at the Pas de Calais.

But Allied bombers were already raining down fire on enemy positions and, as the sun rose over the Normandy coast at about 5 am, the invasion fleet opened fire.

German observers spotted the approaching armada that, for the next two hours, blasted the shore and deposited thousands of men on the five invasion beaches. A German lieutenant named Frerking, at strongpoint WN62, is said to have looked at the sight and said, “But that’s not possible!”

Everything was now ready for the troop landings. All along Sword, Juno, and Gold Beaches, the British and Canadians swarmed ashore.

Lieutenant Michael Aldworth and about 40 men crouched in their landing craft as shells exploded around them. Someone asked him how long it would be, and he called, “Wait a minute, chaps. It’s not our turn.” After a moment someone asked, “Well, just how long do you think it will be, old man? The ruddy hold is filling full of water.”

The craft was going under. The men from the sinking craft were picked up by several boats, with some delivered to the beach and others taken out to a Canadian destroyer. One officer, Major de Stackpoole, is said to have dived overboard and began swimming for shore, not wishing to be out of the fight.

Sword Beach

At 5:30 am, the big transport ships began to disgorge small landing craft packed with troops into choppy seas. As they plowed toward the beach in heavy seas, many men became violently seasick.

To buck up his men, Major “Banger” King of the East Yorkshire Regiment recited passages from Shakespeare’s Henry V, including the famous passage, “Once more unto the breach.” As men and equipment approached the beach, Allied warships fired at German strongholds. This was reinforced by field guns of the 3rd Division’s own artillery firing from ships up to six miles back from the coast, enabling most of the craft to approach the beach without significant damage.

Sword Beach was on the eastern edge of the Normandy invasion site, stretching eight miles from the Orne estuary at Ouistreham to St.-Aubin-sur-Mer. From east to west Sword was sliced into four sectors, called Roger, Queen, Peter, and Oboe, although rocks kept the 3rd British Division from landing on Peter and Oboe.

The 8th Brigade Group formed a spearhead, attacking defenses on Queen Beach. The British assault force combined infantry, commandos, and specialized armored units, which formed a template for the battles that would be repeated on the other two British-Canadian beaches.

The incoming tide at Sword Beach was already higher than expected. It meant several landing craft crashed into obstacles that the Allies had thought would be visible above water, and it made the beach narrower. That helped by cutting down the space the infantry would need to dash across, but it also cut down space for armored vehicles to assemble. By 7:30 am, two regiments were on the beach and battering their way forward supported by armored firepower.

For two hours they pushed on and captured at last the coastal strongpoint at la Breche. But it was not without a steep price. One observer described this section of beach as “a sandy cemetery with unburied new dead and half undead, missing arms and legs, their blood clotting in the sand.”

Other British and French troops fought into the outskirts of Ouistreham, driving two miles inland to capture Hermanville-sur-Mer. Troops continued to land on the narrowing strip of beach, hampered by a traffic jam of armor. By noon, the British 185th Infantry Brigade pushed inland without supporting armor, which would catch up when possible.

Gold Beach

Gold Beach was the westernmost British-Canadian sector, a nine-mile stretch from la Riviere to Port-en-Bessin in the west. The sectors were named King, Jig, Item, and How. Rocks squeezed the British 50th Infantry Division assault into the King and Jig Sectors only.

Between 5:45 and 7:15 am, Allied naval vessels bombarded the defenses, helped by 72 artillery pieces handled by the 50th Division. Sgt. Maj. Jack Villader Brown said these artillery pieces fired rapidly for so long that “the guns got so hot the blokes could hardly handle them.”

At 7:30 am the 69th Brigade assaulted King Sector with two infantry battalions backed by specialized armor, while a similar group from the 231st Brigade and a Royal Marine Commando unit landed on Jig Sector. Again, the naval bombardment aided the landings.

Farther west, the German-held village of le Hamel stood firm despite being pounded by Allied Hawker Typhoon fighter bombers. The armored support wasn’t enough to prevent the Hampshires from becoming pinned down opposite le Hamel.

Private Hooley from A Company said later, “A sweet rancid smell, never forgotten, was everywhere; it was the smell of burned explosive, torn flesh, and ruptured earth.” He watched as a flail tank exploded, “out of which came cartwheeling through the air a torn, shrieking body.”

Despite terrible carnage, the British forces secured the beach by around 9:30 am. The le Hamel battle carried on until afternoon as the 50th British Division pushed inland four miles to the town of Cruelly; a few units went west to grab Port-en-Bessin and close the gap with the Americans at Omaha Beach.

The British and Canadians made full use of amphibious tanks and armored vehicles. Cornelius Ryan wrote, “Some, like the flail tanks, lashed the ground ahead of them with chains that detonated mines. Other armored vehicles carried small bridges or great reels of steel matting which, when unrolled, made a temporary roadway over soft ground. One group even carried giant bundles of logs for use as steppingstones over walls or to fill in antitank ditches. These inventions [known as ‘Hobart’s Funnies,’ after their inventor, Maj. Gen. Percy Hobart], and the extra-long period of bombardment that the British beaches had received, gave the assaulting troops additional protection.”

Juno Beach

Meanwhile, at Juno Beach the Canadians, sandwiched between the two British beaches, found their place in the sun and in the mud. In the first wave, there were about 3,000 Canadians of all ranks (11,000 more would follow) who stormed Juno Beach, which stretched six miles from St.-Aubin-sur-Mer in the east to la Riviere. In the middle was the small fishing port of Courseulles-sur-Mer. To the east lay two smaller villages, Bernières-sur-Mer and St. Aubin.

Juno was divided into three sectors: Nan, Mike, and Love, and the landing places fairly bristled with guns, barbed wire, concrete emplacements, and mines. Keller’s men not only had to contend with the obstacles and small-arms fire, but also came under intense mortar fire.

The initial assault was handled by four regiments with two companies supporting the flanks: The North Shore Regiment on the left at St. Aubin (Nan Red Sector), the Queen’s Own Rifles in the center at Bernières (Nan White Sector), the Regina Rifles at Courseulles (Nan Green Sector), the Royal Winnipeg Rifles on the western edge of Courseulles (Mike Red and Mike Green Sectors), with a company of Canadian Scottish securing the right flank and a company of British Royal Marine Commandos securing the left flank.

The Canadians rushed through curtains of machine-gun fire and attacked the pillboxes with Sten guns, small-arms fire, and grenades. The first wave took heavy casualties. When tanks arrived, the pillbox defenses were largely decimated, and in hand-to-hand fighting the Canadians cleared the enemy positions. In less than two hours, they managed to secure the first offensive routes off the beach.

One of the toughest pockets of resistance was met by the Canadian 3rd Division when the men ran into lines of pillboxes and trenches in Courseulles, then fought through fortified houses and from street to street. In many cases the fighting was hand to hand.

Farther west at 7:45 am, the 7th Canadian Brigade Group approached Mike Sector. John Wesley Pointon from Saskatchewan was hunched down inside his landing barge.

Pointon, loaded down with a 50-pound radio and 60 pounds of other gear, was just one man among 300 in the belly of the craft.

His barge hit a mine just offshore. “We had to jump over the sides,” he remembered, but his precious signal radio was sealed in waterproofing material. “Most of our group got safely on shore, but we had no transport. Our trucks were useless in the barge where the mine had blasted the landing ramp.”

Then came the part Pointon didn’t want to talk about, even decades later. The first wave of infantry had landed ahead of them, to face the German pillbox defenses—bunkers where tiny slits were spitting out machine-gun bullets that cut down men like mown hay.

Pointon and his buddies clambered ashore, moved through the dead and wounded strewn on the beach, and pushed past the pillboxes. A few miles inland and a few hours later, Pointon found himself among a handful of men pinned down by a sniper shooting from a tiny church balcony.

Ironically, it reminded him to pray. He worried that he’d strayed from his strict Canadian prairie Christian upbringing. He’d been named John Wesley after the famous founder of Methodism, but he had little time to dwell on how he’d wandered from those ideals or on thoughts of his brand-new wife and his parents back home in Saskatchewan.

The events of the present became a blur. He had walked a long way, passing through a small village. Signal Corps men were not heavily armed because they weren’t supposed to be combat soldiers, but even the support troops were running out of ammunition; the men’s extra ammunition was back on the barge. They simply hunkered down and hoped the enemy fire would go overhead.

Pointon concentrated on his radio. Amid the confusion, the Signal Corps had to keep relaying messages. They picked up crackling frontline messages and passed the information to headquarters and then back again. The wireless communication chain went all the way to England. They dared not make a mistake. Pointon remembered his Morse code and did his job with trembling fingers.

Fighting Inland

Throughout the morning, Canadian and British commandos pushed forward through St. Aubin and Courseulles and advanced about four miles inland. At every move, pockets of enemy forces harassed their steps and held out in the coastal villages until early evening.

The Regina Rifles and Royal Winnipeg Rifles fought their way through Courseulles and Graye-sur-Mer. The North Shore Regiment captured St. Aubin, while the Queen’s Own Rifles took the town of Bernières.

CBC News gives a helpful minute-by-minute account of D-Day as compiled by Robin Rowland. He summarized the Canadian invasion at Juno this way: “At 8 am, the first Canadian beachhead is established in Courseulles in Mike Sector by the Regina Rifles, covered by the tanks of the 1st Hussars. Naval gunfire had taken out the German guns in their area, but nearby the Royal Winnipeg Rifles come under heavy fire—there the navy had missed the German guns and many of the soldiers died in the water, never reaching the beaches.

“In the Nan Sector, the North Shore Regiment lands under heavy German fire. At 8:30 am, the Queen’s Own Rifles land at Nan Sector, held up by high seas. The soldiers have to run 183 meters [200 yards] from the shore to a seawall under fire from hidden German artillery. Only a few men of the first company survive.

“At 10 am, Canadian soldiers are on the beach in all sectors. Reserve troops begin to reach the beach on the rising tide. While the Canadian Scottish suffers only light casualties, the landing craft bearing Le Regiment de la Chaudiere hit hidden mines, killing many men. Others drowned trying to reach the shore.

“At 10:30, Major General R.F. Keller, Canadian commander at Juno, sends a message to his superior, General H.D. Crerar: ‘Beach-head gained. Well on our way to our immediate objectives.’”

By noon, all units of the 3rd Canadian Division were on shore at Juno Beach. By that evening, the North Shore Regiment would capture St. Aubin, and in the next few hours other Canadians would take Courseulles and Bernières. Later, the Highland Regiment took Columbiers-sur-Seulles. The First Hussars reached its objective at the Caen-Bayeux highway intersection—the only Allied unit to capture its planned final objective on D-Day.

Moving Inland Together

As this historic day progressed, few individual soldiers on the ground grasped the big picture, but a bird’s-eye view would have shown the Allies advancing farther inland from the five separate beaches to form two larger beachheads.

Advancing south four miles from Sword, elements of the 185th Brigade reached Biéville, while No. 45 (Royal Marine) Commando, part of the 1st Special Service Brigade under Lord Lovat, thrust south-southeast and crossed Pegasus Bridge to link up with the airborne forces located east of the Orne River. The commandos then continued northeast to relieve the paras at the Merville Battery.

Meanwhile, as No. 41 (Royal Marine) Commando attacked the town of Lion-sur-Mer, the 8th and 9th Infantry Brigades pushed southwest, but German resistance stalled their drive on the Periers Ridge. Elements of the German 21st Panzer Division then attempted to smash toward the coast through a three-mile gap that existed between the Sword and Juno beachheads. Determined resistance prevented all but a small enemy force from reaching the coast.

Meanwhile, the 3rd Canadian Division had moved forward to five miles inland across a five-mile front, from Anisy in the east through to Cruelly. There the Canadians linked up with the 69th Brigade, 50th Division, which had moved six miles south from Gold Beach to the town of Coulombs.

Farther west, the 50th Division’s other two brigades had moved five miles southwest to reach a position just two miles short of Bayeux. By nightfall, parts of two British divisions had started disembarking onto the beaches at Normandy to reinforce the Allies.

Farther west, American forces pushed inland from Utah Beach to link up with airborne forces. At Omaha Beach, where fighting had been difficult all day, Americans managed to drive inland to secure a precarious four-mile-wide by one-mile-deep foothold on French soil. The cost of the bloody Omaha battle was more than 2,000 casualties.

Once ashore, speed was paramount. From Gold Beach, British troops headed for Bayeux, seven miles inland. From Juno, the Canadians plunged onward for the Bayeux-Caen highway and Carpiquet Airport, about 10 miles inland. From Sword, the British headed for Caen.

Night fell, and Allied troops pushed on. By midnight, 159,000 Allied troops had grabbed four sizable beachheads. The Sword Beach operation had linked up with the 6th Airborne at Pegasus Bridge and the Merville Battery to carve out a 25-square-mile stretch, while the Juno and Gold forces had joined up to secure a 12-mile-wide beachhead; farther west were the two American beachheads.

The price of victory was high. The battles for the Juno beachhead on D-Day cost 340 Canadian lives and another 574 wounded; during the first six days of the Normandy campaign, 1,017 Canadians would die, and by the end of the campaign 5,020 Canadians would be dead. Despite the excruciating cost, D-Day was a stunning success. It established the coveted second front, and was a crucial step on the march to victory.

American, British, Canadian, and some French forces had established a beachhead in France. Maybe it was just a toehold, but it signaled one of the most successful military operations of all time.

Although the Canadians had been the last of the five Allied divisions to land, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade had penetrated six miles inland from Juno Beach, farther inland than any other. They were headed for Caen, a vital center of road and railway networks that radiated throughout Normandy and on to Paris.

News Reaches Home

The first bulletins arrived at CBC headquarters in Toronto around 3:30 am on June 6. Although details were scant, the first CBC broadcast on June 6 opened with: “The invasion of France began early this morning. Thousands of Canadian, British, and American soldiers are storming the beaches of what Hitler called ‘Fortress Europe.’”

Headline stories hit newspapers and other media outlets around the free world.

In Britain, one read, “British Prime Minister Winston Churchill has told the House of Commons in London that an armada of 4,000 [sic] ships has crossed the Channel to France. Mr. Churchill says the sea passage was made with minimal losses. The enemy was caught by surprise. The attack began shortly after midnight in France, with heavy bombardment by the planes from all Allied Air Forces. Airborne troops were dropped by parachute in key locations and it is reported they have captured most of their objectives.”

Another reported in Washington, “President Franklin Roosevelt has told reporters in Washington that minesweepers and PT (patrol torpedo) boats cleared the way for the fleet. Two U.S. destroyers and one LST (landing ship tank) have been lost.”

At Allied headquarters in southeast England, a third stated, “The Canadian 3rd Division has landed at a beach codenamed Juno. The attack began just before 8 am local time, three hours before low tide. There are reports of casualties on the landing craft due to beach obstacles and bombardment by the enemy. Heavy fighting is reported near the town of Bernières where the Royal Winnipeg Rifles landed just after dawn.”

Back in Canada, Prime Minister Mackenzie King issued his official statement (preserved in CBC archives): “At half past three o’clock this morning, the government received official word that the invasion of Western Europe had begun.

“Word was also received that the Canadian troops were among the Allied forces who landed this morning on the northern coast of France. Canada will be proud to learn that our troops are being supported by units of the Royal Canadian Navy and the Royal Canadian Air Force.

“The great landing in Western Europe is the opening of what we hope and believe will be the decisive phase of the war against Germany. The fighting is certain to be heavy, bitter and costly. You must not expect early results. We should be prepared for local reverses as well as success. No one can say how long this phase of the war may last. But we have every reason for confidence in the final outcome.”

After D-Day

Expanding the beachhead had its share of problems. On June 7, the North Nova Scotia Highlanders and the 27th Armoured Regiment (Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment), pushing toward the Carpiquet airfield, were attacked by SS Colonel Kurt Meyer’s 25th Panzergrenadier Regiment and the 50 tanks of the 12th SS Panzer Regiment Hitlerjugend at Saint-Germain-la-Blanche-Herbe, near Caen. The Germans inflicted heavy losses on the Canadians and destroyed 28 tanks.

A group of Canadians was captured by the Germans and herded into the walled courtyard of the Abbey Ardennes. On June 7 and 8, 20 unarmed Canadian prisoners of war were taken into the serene courtyard and murdered by Meyer’s men, each shot in the back of the head.

Unaware of the atrocity taking place at the abbey, three “Grizzly” tanks (the Canadian version of the Sherman) of the 1st Hussar’s C Squadron (Canadians) drove toward Carpiquet airfield and advanced all the way to the Caen-Bayeux railway line. It was the only unit on the whole of D-Day to reach its final objective (although they had to withdraw for lack of reinforcements). The Canadians finally captured Carpiquet airfield on July 5.

Despite the failure to capture any of the final D-Day objectives that day, the Juno Beach assault is considered by many historians to be the most tactically successful of the D-Day landings alongside the American landing at Utah.

In about a month, Cherbourg was captured, providing the Allies with a port besides the artificial Mulberry ports they had towed with them across the Channel, and the British and Canadians had finally battled their way into Caen to dismantle a keystone of the German defenses.

The 3rd Canadian Division’s commander, however, suffered his share of criticism during and after D-Day. Maj. Gen. Keller was not highly regarded by British corps level commanders before II Canadian Corps had been formed on the Continent. The division’s performance was rated as having “immense dash and enthusiasm” on D-Day followed by “the rather jumpy, high-strung state of the next few days, and then a rather static outlook.”

Keller himself was described as having gone through the same phases, and his corps commander felt the division would “never be a good division so long a Major General Keller commands it.” His own staff officers thought him to be anxious and overly concerned for his own safety.

After II Canadian Corps was activated in the field, Keller was confronted by his new corps commander, Lt. Gen. Guy G. Simonds. Keller surprised Simonds by reporting himself to be in ill health and seeking to be relieved. Simonds in turn acted surprisingly by refusing and asked Keller not to be hasty. The next day Keller agreed to continue in command of the division.

After three more weeks, Simonds changed his mind, but by then Keller had become the only Canadian general wounded in action in World War II when Allied planes bombed his headquarters by mistake. Simonds later stated, “I was saved from a very embarrassing situation by Keller being wounded and invalided home before I had to act, which I had become convinced was necessary.” Keller was replaced by Maj. Gen. Daniel Spry.

More victories followed—including the liberation of Holland where Canada played a vital role—as well as setbacks. Germany finally surrendered on May 7, 1945.

After the War

Six months later, John Pointon returned to Canada aboard the Queen Mary, one of 740,000 men and 36,000 women who served Canada in World War II. There were heavy casualties; 42,042 Canadians had been killed and 54,414 wounded. Pointon was thankful that he was able to come home to live a quiet life, drive his taxi, and raise his family.

It took men like Pointon and all the Allied forces together to stop what Prime Minister MacKenzie King had called “this violence, this terror, this ruthless iniquity” of Nazism. It took the foot soldiers, the men in the skies, the men at sea, and the men who passed the signals. It took the fallen and the survivors. They were all heroes.

Like many others, D-Day was John Wesley Pointon’s finest hour. He went to his final reward in the year 2000 at age 82.

Normandy Today

Among the memorials of Normandy today stands Juno Beach Center, a museum built close to the place where Canadians landed during the D-Day assault. The center’s website says, “The Juno Beach Center at Courseulles-sur-Mer in Normandy will provide recognition of Canada’s military and civilian contributions during the Second World War. It will preserve for future generations the knowledge of the contributions of that generation of Canadians and honour the gifts of valour and freedom that were given by all Canadians who participated.”

The museum opened June 6, 2003, after a seven-year effort. Eighty-year-old Alex Kowbel, a veteran of D-Day, said at the unveiling of a memorial at the site, “We tend to forget, so this memorial will help people remember.”

A memorial to the 20 murdered Canadians also exists in the garden of the Ardennes Abbey in Saint-Germain-la-Blanche-Herbe.

Dr. Serge Durflinger, historian at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, said, “D-Day itself was piercing the crust of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall. After Canada was a major player in doing that, I think the army gained a lot of confidence, a lot of maturity, and they had proven themselves in the test of combat.”

British historian John Keegan paid tribute to the Canadian 3rd Division on D-Day: “At the end of the day, its forward elements stood deeper into France than those of any other division. The opposition the Canadians faced was stronger than that of any other beach, save Omaha. That was an accomplishment in which the whole nation could take considerable pride.”

My dad was RCAF ground crew for Typhoons at the time of D-day. My uncle landed on Juno.

First time reading about the Canadians very enjoyable article. More please

My uncle went in with the Canadian Parachute Regiment attached to the British on D-Day.

Only 18 years of age. He never talked about the war too much. D-Day was just the beginning for him

until the war was finally over.

Bob

Thanks for this.”Often Overlooked” yes so it’s nice to read something like this.I knew many of the ww2 veterans in our little town in Ontario,and was fortunate enough to know two men from ww1.We can’t thank them enough for their service to secure our freedom.Greates generatin for sure!!!