By Stephen L. Wright

The jerk of the canopy opening was a reassuring sensation. Not so reassuring was the storm of small arms and artillery fire that roared up from the ground. The troopers from the 513th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), 17th U.S. Airborne Division, had already been shaken around in their aircraft by the buffeting of antiaircraft shells.

Along with their fellow troopers and airborne colleagues from the British 6th Airborne Division, they had trained hard for this moment and they were ready to do their job: to seize, clear, and secure German-held positions east of the Rhine. It was Saturday, March 24, 1945, and Operation Varsity, the largest single lift in history, was under way.

The Airborne Component of Operation Plunder

Varsity was the parachute and glider component of a larger operation known as Plunder, designed to breach the Rhine at Wesel and complement two earlier American crossings of Germany’s major waterway.

The two divisions had only been out of the line for two months, having suffered heavy casualties in the brutal and bitter conditions of the Belgian Ardennes. They were, respectively, part of Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway’s 18th U.S. Airborne Corps and Maj. Gen. Richard S. Gale’s 1st British Airborne Corps, together forming the First Allied Airborne Army.

The 6th had entered the Ardennes as a veteran outfit, having fought throughout the Normandy Campaign under Gale, its founding CO. An experienced paratrooper, Gale had previously commanded the 1st Parachute Brigade during the Normandy invasion.

The division would fly to Germany in its original format of two parachute brigades, each of three battalions, and a glider-borne airlanding brigade, again comprising three battalions. Support was provided through artillery, medical, signal, and engineer units. Maj. Gen. Eric Bols would be Gale’s successor.

For the 17th, the Ardennes had been its baptism of fire. Its CO, Maj. Gen. William “Bud” Miley, like his British counterpart, was an experienced paratroop commander who had followed the traditional route of Army service. In 1940, he was given command of the 501st Parachute Battalion, thus becoming the first American officer to command a designated airborne unit. After time with his battalion in Panama, he returned to the States in 1942 to take charge of 503rd PIR.

Three months later he was promoted to command the 1st Parachute Brigade. He served for a short time as assistant commander of the 82nd Airborne Division before taking command of the 17th. Following the losses in the Ardennes, particularly in the 193rd Glider Infantry Regiment, which was all but reduced to nothing, Miley instigated a new table of organization and equipment.

Consequently, the division would field three combat teams (two parachute and one glider) with support for the 6th. The other parachute regiment was the 507th PIR which, until the Ardennes, was the only unit of the 17th to have previously seen action.

The 9th U.S. Troop Carrier Command (TCC) provided paratroop transport for both divisions and gliders for the 17th. On September 1, 1944, it was reassigned to the U.S. Strategic Air Force, for administration control, and the First Allied Airborne Army for operational control.

The Royal Air Force’s 38 and 46 Groups were part of that organization’s Transport Command. Ordinarily, they carried the 6th’s paratroopers and towed the airlanding gliders, but for this operation, the latter role would be the task of the 9th TCC.

The Glider Pilot Regiment (GPR) would provide transport for the Airlanding Brigade. Its members were all volunteers from the many regiments and corps throughout the British Army, and they had been trained to fly and to fight. The regiment’s greatest loss to date had been in Holland during Operation Market-Garden. Time was not available to train new pilots, so RAF pilots were drafted in.

Objective: Wesel

Ridgway was given operational command. He met General Miles Dempsey, C-in-C British Second Army, on February 14 and was given a broad outline of the overall plan; Gale was appointed his deputy.

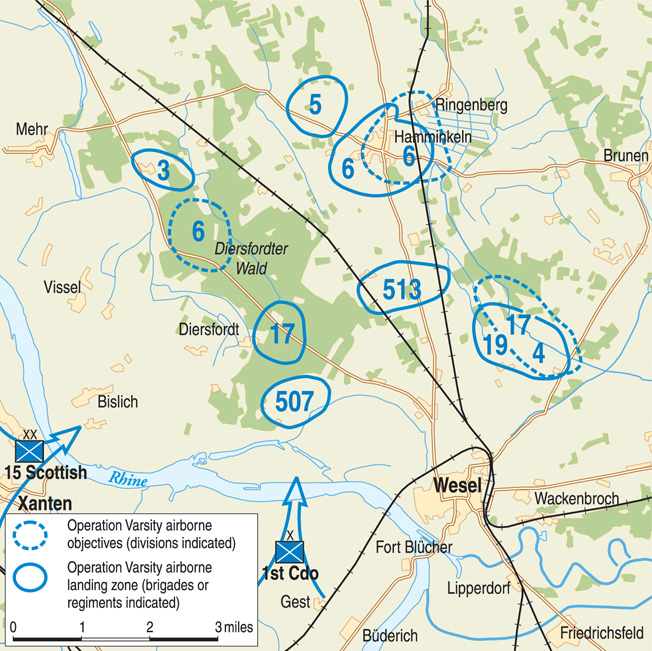

Careful study of the photographic reconnaissance of the area showed that suitable drop zones and landing zones were available adjacent to the immediate objectives. In an attempt to disperse the enemy’s attention and fire, 10 zones were chosen, seven for the 6th and three for the 17th.

The 6th Airborne would be required to land on the northern edge of the Schnepfenberg, a high feature topped by the Diersfordter Wald, opposite the point at which British XII Corps would cross the Rhine on the outskirts of the village of Hamminkeln and beside two road bridges across the Issel Canal. The parachute brigades would take care of the first area. The Airlanding Brigade (12th Devonshire Regiment) would secure Hamminkeln and capture two road bridges and one railway bridge. In a repeat of the initial landing in Normandy, Company B of the 2nd Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry and Company D of the 1st Royal Ulster Rifles would execute a coup de main landing on the bridges.

The town of Wesel and its environs were the main objectives of the 17th. The parachute regiments were to drop to the south and east of the Schnepfenberg while the gliderborne elements were to land to the north of Wesel. Tasks included seizing a bridge over the Issel, which ran along the eastern edge of the landing area. While not a particularly wide river, the Issel’s steep banks were a natural tank trap. The 194th was also to protect the right flank of the landing, and establish contact with the British 1st Commando Brigade, which was expected by then to have captured and secured Wesel.

Tactical Glider Landings

The 513th and artillery forward observers would jump from the two-door Curtiss C-46 Commando aircraft, and its glider troops would be in double-towed gliders. This technique had been tried the previous year, unsuccessfully, in Burma.

For the first time, glider troops would be landing in unsecured zones. For this reason the gliders were to execute tactical landings to confuse the defenders about the direction from which the main attack would come and to enable troops to land as close as possible to their objectives.

This latter innovation had, like several other factors of the operation, been influenced by the contents of a captured German document, which had come into the Allies’ possession in December 1944. This was an appreciation of the mistakes made in Operation Market (the airborne phase of Market-Garden).

The document found fault with the Allies’ failure to put down the maximum force possible on September 17; slowness in building up forces, following the first lift; keeping to the same route in resupply missions and a concern to overprotect the immediate drop zone area rather than put pressure on German forces. This latter failure allowed the Germans to concentrate troops and organize rapid counterattacks.

Following their findings, the Germans put into place measures that would seek out areas most likely to be chosen for large-scale airborne landings. Antiaircraft and mortar defenses would be concentrated on these areas. Air raid precautions would be improved, and new mobile patrols, trained for antiairborne defense and capable of mobilization at 20 minutes’ notice, would be created.

In all the reorganization, the 194th Glider Infantry Regiment was still short one company. Following a request from Miley, Captain Charles O. Gordon, glider operations officer with the 435th Troop Carrier Group (TCG), made an immediate decision that his pilots could handle this assignment based on his knowledge of their previous combat experience and the use of various weapons. They received two weeks’ infantry training from the 194th.

As mentioned earlier, the GPR suffered grievously during Operation Market-Garden. With the ensuing airborne operation leaving too little time to train new pilots from scratch, the decision was made to bring in RAF pilots. For some of these, their posting to the GPR is remembered and regarded as more by foul means than fair. Be that as it may, they all played an important role in the GPR at that time.

“Axis Sally Knows We Are Coming”

Following the push to the Rhine, the Allies were faced with the remains of the German First Parachute Army, the 84th Infantry Division and its supporting armor, and the 47th Panzer Corps with the 116th Panzer and 15th Panzergrenadier Divisions. On March 10, the German forces crossed the Rhine using a heavy rainstorm as cover and blew the last bridge behind them. At this time, the Allies estimated that the Germans had lost some 40,000 killed and over 50,000 captured.

The panzer divisions had also been badly mauled by the intense assault of the combined Allied presence. Estimates of the number of enemy troops occupying the crossing and invasion area vary: 7,500-12,000 with 100-150 armored fighting vehicles and their crews available in support. More significantly, and proving that the Germans expected an airborne landing, approximately 800 antiaircraft guns were noted in the week running up to the operation.

In overall command was Generaloberst Alfred Schlemm, CO of First Parachute Army. Using what time he had, Schlemm ensured that defensive works were constructed to secure or cover all areas that could be used for waterborne or airborne landings, height advantage, or speeding movement through and beyond the defensive zone. Farmhouses and suitable farm buildings were also turned into strongpoints.

Understandably, as the operation drew closer security was stepped up. So it seems rather odd, then, that a reconnaissance flight of tugs and gliders was sent along the planned route for Varsity. The exercise, or Operation Token, as it was officially known, was carried out without incident and, of course, as secretly as possible.

Nevertheless, there was a widespread belief that the Germans were ready for the landings. The taunts of radio propagandist Axis Sally to the 17th Airborne were taken in good stead. The joke among the troopers was: “Axis Sally knows we are coming, and we know she knows, but she doesn’t know when.”

Operation Varsity Gets Off the Ground

Final briefings took place on March 22 and 23. On the 24th, dawn was just breaking as the British and Canadian troopers left for their respective airfields; in France, dawn revealed the 17th’s airfields as the spawning of a huge new airborne invasion. With the time difference, the Americans would be taking off as the Commonwealth contingent passed overhead.

At 8:20 am, artillery units of medium, heavy, and super-heavy guns dug in on the west bank of the Rhine, began to bombard the German positions in two phases; the second was to end as the first transports passed overhead at 10 am. As it happened, the planes arrived six minutes early.

The German defenses were not subdued for long and began a steady and accurate fire as the troop carriers approached, crossed, and turned away from the zone.

Across the whole area stretched a smoke screen that rose up to 2,500 feet; it was Montgomery’s idea to cover his river crossing with smoke, but it caused severe harassment and problems for the airborne element.

The 513th was dropped a mile off the zone, where the 12th Devons’ gliders were headed. The C-46 of the executive officer, Lt. Col. Ward Ryan, was burning as he and his stick hooked up; the men landed in the middle of a German artillery command post. The regiment’s CO, Colonel Jim Coutts, slipped out of his harness, walked through the machine-gun fire, and began to attack before he had a battalion. The misdrop was fortuitous for the Devons, as it meant their zone was cleared.

As Company E of the 513th’s 2nd Battalion was approaching a farmhouse, it came under fire. It was here that the actions of Pfc. Stewart Stryker led to his posthumous Medal of Honor. With no regard for his own safety, Stryker left cover and ran to the front of a pinned-down platoon. He encouraged its members to follow him, which they did. Stryker only covered a few more yards before he was cut down, dying as he fell. He had done enough, though, and the house was taken.

For the 513th’s comrades in the 507th, its 1st Battalion suffered a similar fate, landing 21/2 miles off zone. The 507th’s CO, Colonel Edson D. Raff, quickly realized that the woods were east and southeast, not north and northwest. Soon, men came from various directions, and Raff assembled a solid fighting force.

Assault on Diersfordt Castle

Enemy machine-gun and artillery fire was coming from the village of Diersfordt and the nearby woods, and a battery of five 150mm guns was also firing. Raff detailed a party to capture the guns, while he and the remaining troopers engaged in clearing the woods and taking the village.

About 11 am, Raff and his men were close to Diersfordt castle, an objective, when they met up with another group from 1st Battalion led by Major Paul Smith, whose group had landed closer to the village. With the majority of the 1st Battalion now assembled, an immediate assault was made on the castle.

Company A led the attack, but just as the remaining companies were about to be committed, Company I from the 3rd Battalion arrived. Since the castle was an objective of this battalion, Raff withdrew the 1st Battalion, less its lead company, and ordered it to proceed in its primary role as regimental reserve.

The 2nd and 3rd Battalions were dropped squarely on their DZs and assembled quickly against heavy machine-gun, small arms, and light artillery fire from enemy troops dug in in the woods north and east of the zone. One of the members of the battalion was also to be awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor. Private George J. Peters singlehandedly attacked a machine-gun position that was preventing his group from reaching its weapons.

“I Want You to Be Merciful”

Private First Class John Kormann was a member of the 517th Signal Company attached to the 507th; his glider had received intense antiaircraft fire and had crashed into a grove of trees. All the occupants were thrown out, and upon coming to his senses Kormann found himself alone with a lot of gunfire and mortar shells exploding close by. He grabbed his gun and, keeping low, made for the woods, where he found a trench running alongside a single-track railroad. He left the woods and joined a group of paratroopers in charging some farmhouses, from which the Germans had been shooting at them.

Bringing up the rear as they passed the last farmhouse, Kormann heard noises coming from a cellar. Convinced that some of the enemy was hiding there, he lifted the slanted wooden cellar door cautiously and was about to toss in a grenade when he remembered the letter he had received from his mother the previous day. She sensed that her son was going into battle. “Son, I want you to be merciful,” she wrote. “Never forget that the young man you are fighting has a mother who loves him and prays for him, just as I love and pray for you.”

Infuriated, Kormann thought: “Mother, what are you trying to do, bring about my death? I am trained to kill or be killed!” Now, he was conscious of his mother’s plea: “Be merciful!” So, instead of throwing the grenade he shouted in German for them to surrender and come out with their hands up. There was silence. His second shout brought stirring. The first to come up was an elderly grandmother. Then another woman appeared, followed by four or five little children. Finally, 14 women and children stood before him. Kormann shuddered at the thought of what he might have done and the burden it would have placed on his life had he not received his mother’s letter.

Under Heavy Antiaircraft Fire

The 194th, with the 681st Glider Field Artillery Battalion in support, was to seize and hold two bridges over the Issel, clear its section of the landing area, defend the line of the Issel River and Canal, and prevent enemy incursion from the southwest.

In the first two serials, four gliders pulled out. Only 29 of the remaining 156 gliders reached the ground undamaged. In the third and fourth serials, 139 gliders arrived but only 18 landed without being hit. The landings were spread across the zone, and a good number of gliders landed outside it.

Companies were assembled within an hour of landing, and moving toward their objectives found a solid German defense, although the enemy’s troops had no real idea where the front line was. They simply attacked U.S. positions as they came across them. Some of their machine guns were overrun, but the American line held steady.

In the British sector, the paratroop and gliderborne battalions also suffered from the intense and concentrated antiaircraft fire. The 3rd Parachute Brigade’s 8th Parachute Battalion was first out, dropping into a wall of fire. Sergeant Ted Eaglen had been wounded in the Ardennes and had returned to his battalion just in time for Varsity. On his way down from his burning C-47, he felt the draft of a shell as it zoomed by. He landed on barbed wire and had a struggle to get out of his parachute––all this while bullets were hitting the barbed wire and whining past him. It seemed endless. He couldn’t believe that he was not being hit. Eventually, he got free and scuttled behind a tree, from which vantage point he saw three Germans. Giving them a burst from his Sten sub-machine gun, he saw them disappear.

Capturing Objectives

Despite all the fury of the enemy’s welcome, Eaglen’s Company C and Company A quickly took their objectives. For Company B it was more of a fight as a well dug-in enemy hung onto a wooded area. The company commander, Major John Kippen, led a ferocious charge through a trench; he was killed in the ensuing hand-to-hand struggle, but the area was taken along with several prisoners. The company’s Antitank Platoon also became caught up in a fierce firefight with a German signals platoon, but the British troopers came out the victors. They arrived at their rendezvous in a captured three-ton truck, which came in very handy in the later gathering of supplies from the gliders.

The brigade’s 1st Canadian Battalion CO, Lt. Col. Jevon “Jeff” Nicklin, a former football star for the Winnipeg Blue Bombers, had landed above a machine-gun position and was shot and killed as he struggled to get free from his harness. His second in command, Major Fraser Eadie, took charge of the battalion. The unit’s main objective was a group of well-defended farm buildings. As with their British mates, the Canadians fought in a determined fashion and took buildings and prisoners.

The 316th TCG aircraft carrying the brigade’s 9th Battalion received a tremendous amount of attention from the German gunners. Of the 37th Squadron’s 21 aircraft, 16 were hit by enemy fire.

One of the aircraft ended up, fully loaded, at Eindhoven’s airfield in Holland. The parachute on one of the parapack containers attached to the underside of the plane had blossomed underneath the door. Attempts to bring the container on board were unsuccessful, and it was too dangerous for the paratroopers to attempt to jump past it. The men were later returned to the front by road.

Another aircraft, flown by the 45th Squadron’s CO, Lt. Col. Mars Lewis, was hit by antiaircraft fire as Lewis executed a left turn from the drop zone. He held the plane straight and level for a few seconds, but the rudder and elevators were burning fiercely. The aircraft went into a diving turn to the right; no parachutes were seen.

Again, as with their colleagues in the other two battalions, the 9th Battalion’s troopers suffered mixed experiences on the ground, some having to fight desperately to overcome enemy positions, others having little difficulty. Within 45 minutes of landing the battalion was almost at full strength and by 1 pm it was dug in by company, A on the Schnepfenberg, B across the main road to the southwest, and C in woodland south of the road.

The quiet of their positions was broken by the arrival of a German assault gun and infantry. The Company B clerk stayed out on the road and slapped a Gammon “sticky bomb” onto the vehicle’s engine cover. The vehicle stopped, and a crewman was shot as he looked out to investigate. The rest of the crew surrendered. The vehicle, still in running order, was taken over by the British and crewed by two ex-tank drivers from the company and, with its German markings covered over, became part of the battalion’s transport for the next week or so.

The 5th Parachute Brigade

In the 5th Parachute Brigade aerial formation, the pilot of the aircraft carrying men of 13th Battalion, which included Captain David Tibbs, the medical officer, had suggested that the troopers jump when they saw the men from the other planes jumping. As the red light came on, Tibbs could see the broad glint of the Rhine below.

Looking out, he and his friend and fellow passenger Sergeant Webster decided that they should not jump until the aircraft had cleared the trees and crossed a line of electric pylons and power cables just beyond the forest. To the men’s horror, they saw that the other two planes in their “V” were dropping their paratroops into the woods and their own dispatcher was motioning the stick to go. Ironically, most of them landed safely but dropped directly in front of a German machine gun, leaving only five survivors out of 30 men.

The 5th Battalion’s mission was to clear and hold an area bounded by roads, a stream, and a collection of buildings; this it did with little opposition. Consequently, the battalion was also dug in by 1 pm. The battalion’s trenches were expertly dug by German prisoners, who seemed quite content with the work, having been told earlier by their superiors that they would be shot by the British rather than taken prisoner.

Meanwhile, the 12th Battalion’s CO, Lt. Col. Ken Darling, had ensured that his men would jump as light as possible. Every other man carried a toggle rope, so no one had any entrenching tools or grenades, and the only spare clothing carried were socks.

In addition, platoons were allocated to aircraft so that members would land on their intended part of the DZ. Flying in the face of the enemy fire, the battalion’s transport group CO, Colonel Howard Lyon, took his aircraft down to about 450 feet before the green light came on. The rest of the serial followed suit. Consequently, the battalion spent little time in the descent and landed close together on the zone.

Disaster struck as Lyon turned for the run back to the river. A shell entered the cockpit, went through his foot, and exited through his knee. Instinctively, he pushed out everything that would make the aircraft climb, which it did. One of the two navigators, Captain Bernard Coggins, helped Lyon out of his seat just as another shell crashed into the cockpit. Lyon took another wound in the leg, as did Coggins, while the co-pilot, Captain Carl Persson, had part of his hand taken off. All the crew managed to bail out and were captured by the Germans. Luckily, the medical aid station where they were taken was overrun by friendly troops and they were freed.

All three companies had a fight to capture their objectives. Company B’s objective—a group of buildings—was so well defended that the buildings could only be taken one by one. In Company A, Lieutenant Phil Burkinshaw also attacked and captured a battery of 88mm guns.

The 7th Battalion in Reserve

While the 12th and 13th Battalions concentrated on capturing the brigade objectives, the 7th Battalion was to land at the northern edge of the drop zone. Its main tasks were to defend the zone and to prevent enemy troops from reaching the brigade’s objectives until the other two battalions had consolidated themselves. At such time, the 7th would move into a reserve position.

Thanks to a well-considered drop plan, the 7th Battalion landed in companies; B and C established themselves in their respective defensive areas and began digging in. Initially things were quiet. Over the next few hours, however, concerted enemy probing attacks kept both units busy. Company B contended with attacks of platoon size or slightly larger, while Company C fought off one determined attack, which was at full company strength.

The glider landings were fraught with difficulties. British war correspondent Stanley Maxted’s glider was one of 12 assigned to the 716th Company, Royal Army Service Corps. Also on board were Lance Corporal Michael Ham; two fellow wireless operators, a Major Oliver, a public relations officer, a Bren carrier, and a radio trailer. Maxted planned to make a live radio broadcast from the field, but things didn’t work out that way. The glider was hit by 20mm shells and crashed close to the Hamminkeln railroad station. The carrier hurtled from the wreckage and Maxted was struck by it. Pilots and occupants managed to get clear and eventually found their way to safety.

On the 3rd Parachute Brigade’s dropping zone, the 6th Parachute Battalion’s CO, Lt. Col. George Hewetson, was briefing his intelligence officer, Lieutenant John England. Two sergeants were standing a few yards away. Suddenly, with a terrific crash a glider came through the trees, and Hewetson found himself lying under the wheel of a jeep. The glider pilots were killed along with Lieutenant England and the two sergeants.

From Quartermaster Major to Pilot in a Matter of Minutes

The Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire coup de main gliders were met with blistering fire. The first glider was seen to break apart; there were no survivors. In the second glider, over half the occupants were killed or wounded. Glider three came down hard but only because its pilots dived earthward to avoid the fate of the others.

The fourth glider had the most remarkable fate of all. Hit by an antiaircraft shell, its nose was sheared off and both pilots killed. One of the passengers, Quartermaster Major Aldworth, was also slightly injured but managed to get one of the pilots out of his seat and occupied it himself. With brief instructions from the towing plane’s co-pilot, Aldworth managed to land the glider, helped by a ditch and a hedge. With nothing more than bumps and bruises, the platoon made its way to the railway station.

On the other bridge, the Royal Ulster Rifles’ gliders fared in a similar manner. One wing of the glider of the company commander, Major Dyball, dug a trench as the aircraft slewed to a stop. The pilots and front passengers went out through the front of the glider and were met by enemy fire. The trench was welcome cover for them as they scrambled toward it.

Dyball’s radio operator was killed as he left the glider, so the commander had no way of contacting his other platoons. He decided to head toward the house that he had chosen as his HQ. As he reached it, he found that 21 Platoon had landed in good order and had taken the house and several prisoners. On the other side of the bridge, 22 Platoon had also had a fight against strong opposition but had captured the bridge. Dyball set up a defense force with support from the Ox & Bucks and glider pilots.

The Only Conspicuous Gallantry Medal of the War

The main parties of both battalions and the men of the 12th Devons landed against similar opposition.

Squadron Sergeant Major Lawrence “Buck” Turnbull’s glider had a platoon of Ox & Bucks on board. As he cast off from his tug and prepared for the landing, a C-47 cut in front of him, and its trailing towrope began to wreak havoc on the glider. First the starboard aileron was torn off, then the lower part of the cockpit with the loss of the air bottles (required for brakes and flaps), most of the instrument panel, and half the control column. As the rope came loose, the Horsa was virtually flipped upside down.

As if all this wasn’t enough, the glider was also the focus of antiaircraft batteries. Showing great calmness, Turnbull managed to right the glider and land without crashing. For his actions he was awarded Britain’s Conspicuous Gallantry Medal—the only one to be awarded to a soldier during the war.

The Ox & Bucks were near Hamminkeln railway station. In the 10 minutes it took to land, the battalion lost half its strength. For several hours some of the survivors played a game of cat and mouse with German Mk. IV tanks, which used stacks of timber as cover. Private battles erupted across the compound and railroad tracks. But, despite all, the battalion’s objectives were taken within the hour, and the companies dug in.

In the Royal Ulster Rifles’ (RUR) sector, both the CO and the adjutant had their gliders break up around them. The adjutant, Captain Robert Rigby, took command and coordinated the neutralizing of enemy strongpoints before organizing a march to the station and level crossing, which were the RUR’s objectives.

Flying Artillery and Armor

In addition to the support from artillery on the west bank of the Rhine, each division was also supported by its own artillery units.

For the U.S. 17th, the 464th and 466th Parachute Field Artillery Battalions supported the 507th PIR and 513th PIR; their 75mm pack howitzers were dropped in parapacks. For the 464th, three of its 12 guns were damaged, but by noon 10 guns were in action. The 466th was dropped on the correct zone and therefore left without infantry support. Before setting up their guns, its members took on an infantry role as they worked to suppress the concentrated fire that swept their zone.

Luck, however, was on the unit’s side as T/Sgt. Joseph Flanagan landed beside a German 20mm gun. He captured it and its crew, and the gun was later used to destroy stronger emplacements. Yet, American losses were significant; all the battery officers were either killed or wounded. Through sheer grit and determination, the 466th continued to ready its guns and began firing.

The 194th GIR was supported by the 681st Glider Field Artillery Battalion; its gunners were under steady fire as they left their gliders and were forced to set up and fire using the glider wings as cover. By 4 pm, 10 howitzers were blazing away, and the battalion continued to give solid support through the rest of the day.

The 680th Glider Field Artillery Battalion had a general support task and was to answer any specific calls from the 513th’s 3rd Battalion. Its gunners also came under fire, and ammunition and guns were lost as transport gliders were hit and set on fire. During the day, the battalion captured three batteries and took 150 prisoners. For its actions it received a Distinguished Unit Citation.

The 155th Antiaircraft Battalion had four batteries, two in support of the parachute regiments, one in an antitank role, and one under control of the 194th. Members of Battery C made good use of their 75mm recoilless rifle.

In the British 6th Airborne, the airlanding battalions had their own antitank guns as part of their support companies, and these were used in varying degrees throughout the day. In addition, the division had the 53rd (Worcestershire Yeomanry) Airlanding Light Regiment RA (Royal Artillery) and the 2nd Airlanding Anti-Tank Regiment. Both units had mixed days, losing men and guns in the landing—a horrifying example of the fury into which the units traveled.

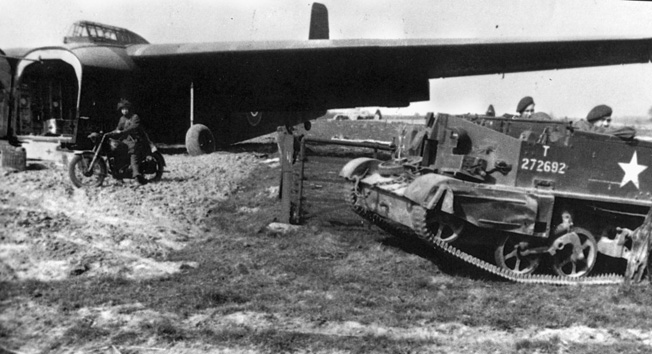

For the second and last time in the war, light tanks were taken directly to the battlefield. Eight of the mighty Hamilcar gliders carried an American M-22 Locust tank and its crew. Seven of the relatively light (eight tons) tanks, purpose-built for airlanding operations, arrived on German soil, and four reached the rendezvous point with a single tank firing in support of the 12th Parachute Battalion. The four occupied a section of high ground in the Devons’ sector and gave support during the rest of the day.

Treating the Wounded of Operation Varsity

For medics on both sides, there was much work to be done.

The 17th’s 139th Airborne Engineer Battalion’s medical personnel were carried in two gliders, one of which landed right beside a defended house. The glider was carrying a medical officer, a medic staff sergeant, a jeep and its driver, and much of the battalion’s medical supplies. The 40 German occupants of the house brought concentrated fire to bear on the glider. A direct mortar hit destroyed the supplies and the jeep and killed the driver; the other two men managed to escape the burning wreckage. With limited equipment, the battalion surgeon had an aid station up and running in no time.

As the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion settled into its defensive positions, one of its medics, Corporal George Topham, was watching the attempts of two members of 224th Parachute Field Ambulance help a wounded man on the drop zone. Under intense fire, the medics made a dash for the casualty but were both killed.

Without hesitation, Topham raced out to the man. Enemy fire continued to sweep the zone, and Topham was shot through the nose. Yet, even in severe pain, he continued to give first aid. He then hoisted the man on his shoulders and carried him to cover. Topham refused treatment and went back into the zone to help more wounded. He also refused to be evacuated and, such was his determination, he was allowed to continue on duty.

Sometime later, as he was returning to his company, Topham came across the mortar platoon’s Bren carrier, which was burning fiercely. The platoon, under Lieutenant G. Lynch, had landed to the north of the LZ and it was during its attempt to reach battalion HQ that its Bren carrier had suffered a direct hit.

Enemy mortar fire was landing in the area, the carrier’s own mortar ammunition was exploding from the vehicle, and an officer was not allowing anyone to approach. Topham didn’t agree and ran to the carrier. In turn, he carried the three occupants to safety. For his gallantry throughout the day, Corporal Topham was awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest military medal.

Despite all the damaged gliders, plenty of stretchers had arrived intact. Private Lenton, attached to the 8th Parachute Battalion, said he would go and get some. His section commander, Staff Sergeant Walsby, said he’d never make it back alive. Undeterred, Lenton and his mate, Private Downey, ran to the gliders. Not only did they make it there and back alive, but they also rescued some wounded men who had been left in the open. For this action, Downey was mentioned in dispatches and Lenton received the Military Medal.

Sometimes adversaries helped to aid wounded enemy soldiers. Captain David Tibbs, having landed safely, made his way to the house he had selected as his field dressing station. Settling into his work, he was surprised by the arrival of a tall, distinguished-looking German officer and several men. The officer saluted Tibbs, wished him a “good morning” and said, “Why have you been so long? We have been up all night waiting for you!” He worked alongside Tibbs for a while, but since there were few German casualties coming in, soon left.

American Corporal Bill Tom arrived in the Wesel zone by jeep. Tom had started his military career as a rifleman in the 194th GIR. By various twists he became a medic-at-large in the Ardennes. When the 17th returned to France, Bill remained with the 9th U.S. Army. On March 24, he had to care for a wounded German soldier who was shot in the head. The man was injured beyond the care of the field medics and was about to be moved to a larger aid station.

Before that could happen, he died and Bill Tom was ordered to move his body to the morgue tent. It was now midnight, and no flashlights were permitted. With the help of a private, Tom carried the body to the area where the morgue tent was located, but in pain from the man’s weight he lost count of the tents (he needed number eight).

He finally saw the one he thought was the morgue tent. Entering, he stepped on something hard and round and fell down. The German was thrown off the stretcher, landing heavily and making a grunt. Tom and the private took off like a shot. The tent was, in fact, the kitchen supply tent and the following morning Tom received a real chewing out from the cook sergeant for scaring his cooks half to death by finding a body on their potatoes.

The planned resupply drop arrived on schedule at 1 pm; 240 Consolidated B-24 Liberators from the Eighth Air Force’s 2nd Air Division each carried 2½ tons, which had been packed into 20 bundles, distributed in three locations: 12 in the bomb racks, five in and around the ball turret (the turret itself had been removed), and three by the emergency escape hatch in the tail. The vast majority of bundles were fitted with parachutes. The planes came in at 100 feet, half to DZ B (6th) and half to DZ W (17th). As with the transports, many did not escape German fire and headed for home with flames streaming from their engines.

“Advance to Dorsten. This is a Pursuit.”

General Ridgway arrived on the east bank around 3 pm. His first stop was Miley’s HQ, where he received a brief report on the day so far. Miley was still concerned that he had yet to hear from Eric Bols at Kopenhof Farm.

As the light began to fade, Ridgway, Miley, and their escort set off for Kopenhof. The convoy’s route ran through the 194th’s sector and then the 513th’s.

Ridgway stopped to get a report from each commander. At the 513th’s HQ, he heard about the misdrop and the ease with which the C-46s had caught fire. He later gave instructions that the aircraft would never be used again to carry paratroops. At Kopenhof, the party also met General Gale.

Ridgway and Miley left the farm about midnight. Fighting was now under way nearby, and they ran into a German patrol. As Ridgway was reloading, a grenade exploded by one of the jeep’s wheels, and he was hit in the shoulder by a piece of shrapnel. The wheel absorbed some of the fragments and undoubtedly saved his life. The Germans were soon driven off, and the party continued to Miley’s HQ.

Both divisions had mixed fortunes during the night. For many men, it was a quiet one, but for the fighting pilots of the 435th TCG it was anything but, as they came into contact with German armor and infantry in a battle that would later be known as The Battle of Burp Gun Corner.

The pilots were well dug in near some houses and a road junction; about 11:30 pm, their listening post reported an approaching enemy tank leading a force consisting of two 88mm self-propelled guns and two mobile 20mm guns with over 200 supporting infantrymen. The pilots laid down a solid field of fire, and a well-aimed shot from a bazooka struck the tank and sent it fleeing back along the road, running over the 20mm guns as it went.

By 1:30 am on the 25th, the enemy had had enough and began to withdraw. The pilots did the same, strengthening the line of defense with their colleagues from the 436th.

Throughout the 25th, the men of the two Allied divisions continued to move deeper into Germany supported by the troops who had crossed the river, meeting little resistance and continuing to take prisoners.

Two days later, Miley gave the order, “Advance to Dorsten. This is a pursuit.” The last drop was over. In less than two months, Hitler’s 12-year Third Reich would be over, too.

Do you have more information on Operation Token both British and American?

Horrible….!.gliders were defenceless against nazi guns.

Never should send them until Germans pounded endlessly

Actually not true, the last Allied Air bourne operation was conducted by the Soviet Army in the far East when they destroyed the Japanese Kwangtung Army in a Blitzkrieg style campaign.

Hi, interesting article. One pointer, if I may, below the picture of the Royal Ulster Rifles (RUR) it states that they took the Merville Gun Battery in Normandy. This is incorrect, the 9th Battalion of the Parachute Regiment assaulted and took Merville.