By John Brown

One blazing hot day in mid-January 1942, Cornelius “Con” Page, an Australian plantation manager and coastwatcher on Tabar Island 20 miles north of New Ireland reported on his radio a Japanese aircraft passing Tabar and heading for Rabaul on the Australian-administered island of New Britain. A few days later, on January 20, he reported two formations of Japanese bombers and fighters, totaling 100, heading for Rabaul (Page was later executed by the Japanese).

“We Who Are About to Die Salute You”

Two of the eight obsolescent Wirraway fighters of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) No. 24 Squadron based at Rabaul were flying patrol at 15,000 feet over Rabaul when the Japanese aircraft arrived. They immediately attacked the bombers, but the much superior Japanese Zero fighters escorting the bombers quickly shot them down.

The six remaining Wirraways of the squadron took off in a desperate attempt to gain height to attack the Japanese. One of them crashed after takeoff, the Zeros shot down two others over the sea, and two crash-landed, riddled with bullets. One survived, its guns empty, to land among falling bombs as the small town and the port were bombed and strafed, as were the airfield, the coastal batteries, and an oil tanker in the harbor.

It was less than six weeks after Pearl Harbor and the Japanese onslaught had reached the South Pacific.

Wing Commander John Lerew, commander of the RAAF at Rabaul, radioed headquarters for modern fighter reinforcements. He was told, regretfully, that HQ was unable to supply any fighters. Next evening, he was asked to attack with any aircraft he could get into the air, a heavily escorted Japanese convoy of transports heading for Rabaul, the transports probably carrying an invasion force.

Lerew signaled headquarters, in Latin—Nos morituri te salutamus, the Roman gladiator’s salutation, “We who are about to die salute you.” He loaded his last remaining Lockheed Hudson with bombs and took off to find and attack a Japanese fleet that included two aircraft carriers, four cruisers, and more than a dozen destroyers and transports. Fortunately for Lerew and his crew, a black night fell and, unable to locate the fleet and with fuel running low, he aborted the mission.

Preparing For the Invasion of New Guinea

On January 21, aircraft from a Japanese carrier fleet raided Kavieng on New Ireland and Lae, Salamaua, Bulolo, and Madang on the New Guinea mainland. On January 23, 5,300 marines and soldiers of the Nankai, the South Seas Force, landed at Rabaul and quickly overwhelmed the 1,400-man Australian garrison. Two thirds of the Australians were taken prisoner, 160 of them were butchered after they laid down their arms, and 400 escaped to march over the steep, jungle-covered mountains of New Britain to the opposite coast and evacuation by ship to the New Guinea mainland.

Also on January 23, the Japanese landed on New Ireland. There the small garrison of Independent Company soldiers (a soldier of an Independent Company was the equivalent of a British Commando) destroyed their stores and the airfield and, all of them suffering badly from malaria, embarked on a small ship and headed for Australia. They were located by Japanese aircraft, strafed, and forced into captivity in Rabaul.

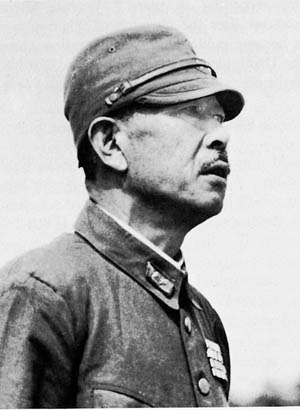

At Rabaul, the Japanese commander, General Harukichi Hyakutake, quickly began building Rabaul and the area around it, the Gazelle Peninsula, into a fortress with naval and air bases and a headquarters for operations in the South Pacific. He gave Maj. Gen. Tomitaro Horii command of an invasion fleet to capture Port Moresby on the southern coast of Papua from where further seaborne operations could be mounted, air attacks made on northern Australia, and sea and air links between the United States and Australia could be disrupted.

The Japanese overall plan was to enclose an area that would include Burma, Malaya, the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), to Port Moresby in Papua, and from there to the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Fiji, Samoa, and on through the central Pacific back to Japan. This vast area, it was thought, could be secured and defended with available naval, army, and air forces and it would provide Japan with its needs for oil, rubber, minerals, timber, and other resources. It would become part of Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Standing in Japan’s path was the continent of Australia. On February 19, 1942, a Japanese carrier force launched two air attacks on Darwin in Australia’s Northern Territory causing extensive damage and sinking eight ships in the harbor; 243 civilians were killed in the attacks––an act called “Australia’s Pearl Harbor.” This would be followed during 1942-1943 by nearly 100 more air raids.

At the beginning of April 1942, the United States assumed responsibility for the whole Pacific area, except Sumatra in the Dutch East Indies; the British took responsibility for Sumatra and the Indian Ocean area. The American sphere was divided in two––the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) commanded by General Douglas MacArthur, who had arrived in Australia from the Philippines, and the North, Central and South Pacific commanded by Admiral Chester Nimitz, with his headquarters in Hawaii. The borderline between their respective spheres came in the Solomon Islands, where a Japanese threat would require action by MacArthur’s ground forces and Nimitz’s naval forces.

Assembling at Rabaul were Japanese ground and air forces to be used for the attack on Port Moresby and the seizure of the island of Tulagi in the Solomons for use as a seaplane base. Behind the amphibious groups destined for the two invasions would be a carrier striking force ready to beat off any American intervention. It comprised the carriers Zuikaku and Shokaku and an escort of cruisers and destroyers.

Battle of the Coral Sea

On May 3, 1942, the Japanese landed on Tulagi and took the island unopposed. Next day planes from the American carrier Yorktown sank a Japanese destroyer. The Japanese carrier group, commanded by Admiral Takeo Takagi, now came south, passing to the east of the Solomons and into the Coral Sea, hoping to take the American carrier force in the rear.

Meanwhile, the carrier Lexington had joined Yorktown and the two were steering north to intercept the Japanese invasion force on its way to Port Moresby. On May 6 the opposing carrier groups searched for each other without making contact, although at one time they were only 70 miles apart.

On the 7th, Japanese search planes reported spotting an American carrier and cruiser, and Admiral Takagi ordered a bombing attack on them. Both ships were sunk, but they were found to be only a tanker and escorting destroyer.

Meanwhile, Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher’s Yorktown attacked the Japanese force heading for Port Moresby and sank the light carrier Shoho. The sinking of this carrier caused the Japanese to postpone their attack on Port Moresby, and the invasion force turned back for Rabaul.

On the morning of May 8, the two opposing carrier forces met in the Coral Sea, off the Queensland, Australia, coast. They were closely matched. The Japanese had 121 aircraft, the Americans 122. Their escorts were almost equal in strength––the Japanese with four heavy cruisers and six destroyers and the Americans with five heavy cruisers and seven destroyers. The Japanese, however, were moving in a belt of cloud while the Americans had to operate under a clear sky.

The aircraft of both carrier forces met in a battle that raged through the morning. The battle was unique in that it was the first large-scale naval action fought between aircraft from opposing carriers, without the opposing fleets ever having the opportunity to engage each other.

The Japanese carrier Zuikaku escaped attention in the cloud cover, but the carrier Shokaku was hit by three bombs and was withdrawn from the battle. On the American side, Lexington was hit by two torpedoes and two bombs, and subsequent internal explosions forced the abandonment of the carrier, a much-loved ship her sailors called “Lady Lex.” Most of the crew were rescued. Yorktown was hit by only one bomb. The Americans came off a little better in aircraft losses––74 compared with over 80, and in men––543 compared with more than 1,000 Japanese. But the Americans had lost a fleet carrier while the Japanese lost only a light carrier. Most important, though, the Japanese had been stopped short of their strategic objective, the capture of Port Moresby.

The Garrison at Milne Bay

In the afternoon, as the threat to Port Moresby had vanished for the time being, Nimitz ordered his carrier force to withdraw from the Coral Sea. The Japanese also withdrew, mistakenly believing that both American carriers had been sunk.

During this time, No. 75 Squadron RAAF flying 17 Curtiss Kittyhawk fighters provided by the Americans was in constant action over 44 days defending Port Moresby against Japanese air attacks aimed to destroy its air defenses, or, led by Squadron Leader John Jackson, raiding Lae and other Japanese-held airfields. Fifty Japanese aircraft were destroyed on the ground or in the air, and 12 Australian pilots were killed or missing. Jackson was killed on April 28 and, on the same day, with only three Kittyhawks still serviceable, the squadron was relieved by two American Bell Aircobra squadrons of No. 35 Group, USAAF. Jackson’s brother Leslie succeeded him as commanding officer of RAAF No. 75 Squadron.

The next Japanese attempt to capture Port Moresby was a double thrust. One group would march from the north Papua coast, cross the Owen Stanley Range of precipitous, jungle-covered mountains, and descend on Port Moresby on the south coast.

The other was to seize Milne Bay on the eastern tip of Papua and use it as a pivot for a seaborne offensive along the southern coast to Port Moresby. In mid-July the Japanese took the first step in these campaigns by seizing Buna and Gona on the north coast of Papua as the jumping off point for their offensives.

Milne Bay is a narrow strip of land between the mountains and the sea, no more than a few hundred yards wide in some places and nowhere wider than about two miles. The huge bay is a natural harbor. At the time there was a mission establishment there and a few plantations and native villages. It was an area of heavy rainfall, and it swarmed with malaria-carrying mosquitoes and countless other insects.

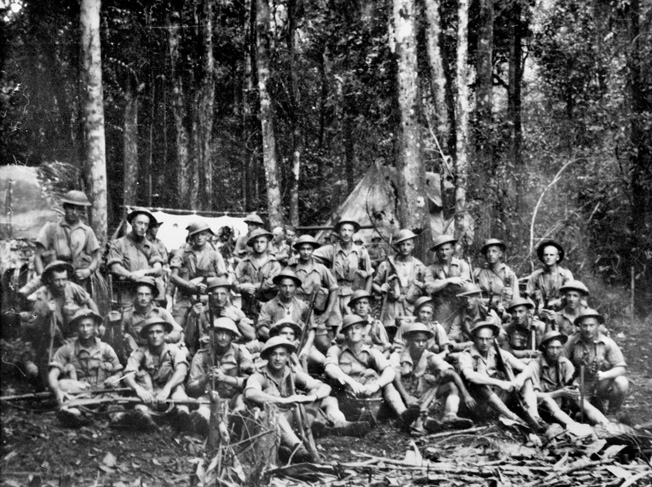

Australian and American troops had been there since late June, building a forward air base. After Buna and Gona fell to the Japanese, the base was reinforced by the Australian 7th Brigade Group of three militia battalions, commanded by Brigadier John Field.

Field, a mechanical engineer and university lecturer before the war, had commanded an Australian Imperial Force (AIF) battalion during the Libyan campaign. His professional skill was of great value in helping to develop, from the ground up, two airfields, roads, bridges, wharf facilities, and a system of defenses.

The garrison was reinforced again in August by the veteran 18th Brigade of the AIF, commanded by Brigadier George F. Wootten, who had served with distinction in the siege of Tobruk. With other reinforcements on their way, command of the area passed to Maj. Gen. Cyril Clowes, a regular officer who had been awarded the Distinguished Service Order and Military Cross in World War I and led the Anzac Corps Artillery during the Greek campaign months earlier. By the end of August 1942, he commanded 8,824 soldiers: 7,459 Australians and 1,365 Americans. They were supported by 75 and 76 Squadrons of the RAAF commanded by Squadron Leaders Leslie Jackson and Peter Turnbull.

Australian Militia vs Japanese Tanks

On August 25, coastwatchers and reconnaissance aircraft reported a Japanese seaborne force with an advance flotilla of seven barges steaming toward Milne Bay. When this was reported, Milne Bay was under air attack, so RAAF pilots were unable to taxi their aircraft away from their dispersal points. But, as soon as the Japanese bombers departed, the RAAF planes took off and swooped down on the barges with bombs and cannon fire. They sank most of them and damaged the others, killing many of the troops in the barges.

The main Japanese invasion fleet was not far behind. It consisted of three cruisers and two each destroyers, troopships, tankers, and minesweepers. The convoy slipped into Milne Bay that night and began disembarking troops.

To protect the base, Maj. Gen. Clowes had deployed his troops so that inexperienced militia soldiers were interlaced with AIF veterans. The 2/10th AIF Battalion was inserted between two militia battalions of the 7th Brigade; they were responsible for the eastern sector and holding the Gili Gili area. The two other AIF battalions of the 18th Brigade and the remaining militia battalion were given responsibility for the western sector.

Before dawn on August 26, some 800 Japanese Marines supported by light tanks were ashore. The Australian militia engaged them in the areas of K.B. Mission and Cameron’s Springs, although they were handicapped by having neither antitank guns nor antitank rifles and fought the tanks with “sticky bombs” that, because of the rain and humidity, would not stick to the tanks.

When the sun rose they could see that the Japanese had landed and piled up stocks of fuel and stores along the shore. Empty landing barges were pulled up on the beach. The RAAF Kittyhawks pounced immediately and, in a storm of antiaircraft fire from the Japanese ships and shore positions, they shot up everything in sight.

During the rest of the day, both sides consolidated their positions, and that night the reinforced Japanese marines attacked again. In dim moonlight, confused fighting went on until 4 am. The marines used flanking tactics that had proved so successful in Malaya, with one group wading neck deep in the sea to get around the Australians on one flank while another group splashed through mangrove swamps or moved silently through jungle in an attempt to turn the other flank.

Hand-to-Hand Fighting

The 61st (militia) Battalion, which had borne the brunt of the fighting from the moment of the first Japanese landing, was almost exhausted by the morning of August 27, 1942, when it was relieved by the first of the AIF battalions. The sun rose to disclose that six more Japanese ships had arrived in the bay, and it was guessed that, from the sounds of landing barges heard during the night, 2,000 or more Japanese soldiers had landed.

The airfields, wharf installations, and supply dumps were all located in the vicinity of Gili Gili, and General Clowes was concerned that further Japanese landings would be made to the south of Gili Gili, an area for which he had no reinforcements. He was therefore moving cautiously until he could be sure of Japanese intentions. General MacArthur criticized him for his caution––he was of the opinion that Clowes should have driven the Japanese back into the sea without delay.

In the late afternoon of August 27, the AIF 2/10th Battalion moved into the defenses around the K.B. Mission. About 500 in all, they had last been in action against the German Afrika Korps in the sun and sand and rocks of North Africa. Now, at 8:00 pm, in darkness, blinding rain, and thick mud, chanting to strike fear in the hearts of their enemies, the Japanese attacked the Australian perimeter. Supported by tanks, the infantry threw themselves fearlessly against the Australian positions and the Australians soon found themselves fighting hand to hand, the battle degenerating into a confusion of group and individual contests.

At midnight the Australians were ordered to withdraw to the west bank of the Gama River. The Japanese followed them so closely that they forced them back beyond the river to the vicinity of No. 3 Airstrip defended by the 25th (militia) Battalion, and here the Australians managed to hold them.

The Australian Militia Holds

The next two days were comparatively quiet except for artillery exchanges and active patrolling by both sides around No. 3 Airstrip. Preparations were made for an attack by Brigadier Wootten’s 18th Brigade to drive the Japanese along the north shore as far as the K.B. Mission and to mop up the whole peninsula, but this was canceled on August 29 when a Japanese cruiser and nine destroyers hove into sight.

Next day, both sides were in constant contact, with the Japanese trying to consolidate their grip on the airfield area and the Australians keeping them out. They were helped by the two Kittyhawk squadrons flying almost continuous sorties, strafing the Japanese from treetop height and acting as flying artillery. They caused heavy casualties, kept the Japanese pinned down, and destroyed their supplies and equipment.

Early on August 31, the Japanese launched three heavy attacks on the 61st Battalion defending the northeast perimeter, but the militia soldiers drove them back leaving many dead and wounded on the muddy ground. By full daylight Clowes was sure that the Japanese were concentrating their efforts along the north shore or eastern sector and thus moved up the first of Wootten’s brigade to counterattack.

All day long the militia soldiers fought their way through a series of ambushes, proving themselves more than a match for the Japanese as they forced them back through slimy mud and dripping foliage until they finally stormed the K.B. Mission at bayonet point as night was falling.

To the rear, 300 Japanese attacked Australians who had taken up positions along the Gama River. At dusk they charged out of the jungle, screaming and chanting. For two hours there was a confused and savage struggle in slashing rain with opponents slithering and splashing in mud that was in places knee deep. After a severe mauling, the Japanese fell back. The Australians followed to finish them off as the enemy attempted to retire westward.

“Expect Attack Jap Ground Forces on Milne Bay Aerodromes”

Clowes felt that he now had the Japanese on the run and planned to continue his advance and mop up the remnants, but at 9:00 am on September 1, 1942, he received an urgent message from General MacArthur, who would later criticize him for caution. The message said: “Expect attack Jap ground forces on Milne Bay aerodromes from west and northwest supported by destroyer fire from bay. Take immediate stations.”

All units prepared to repel this attack, but it never materialized. Two days later, Wootten’s troops resumed their counterattack, but the delay had enabled the Japanese to dig themselves into strongly defended positions. The Australians had to drive them out of each position in a series of actions typical of the one in which Corporal J.A. French took part.

French was leading a section of soldiers that was held up by fire from three Japanese machine-gun positions. He ordered the soldiers to take cover and crawled close enough to knock out two of the positions with grenades, then charged the third position firing a Thompson from the hip. He ran into a hail of bullets. Mortally wounded, he kept moving and firing until he fell dead at the position.

Corporal French had killed the crews of all three machine-gun positions, an action that was responsible for keeping Australian casualties to a minimum and added greatly to the successful conclusion of the attack. He was posthumously awarded a Victoria Cross.

Clowes was confident his troops had broken the Japanese invasion, and he began mopping-up operations. The starving and exhausted Japanese soldiers fought to the end––their refusal to surrender meant that every one of them had to be killed.

Criticism From MacArthur, Praise From Slim

Two weeks after the first landing, the battle for Milne Bay was over. The Japanese had suffered a decisive defeat––their first defeat on land––partly because of their error in assuming that Milne Bay would be held only by two or three companies of soldiers deployed for the defense of the airfields and had expected to overcome them easily with some 2,000 marines and soldiers, and partly because of the splendid backup by the two RAAF squadrons, but mainly because of the fighting spirit of the young militia soldiers who destroyed the myth of invincibility that surrounded the Japanese Army.

But for Maj. Gen. Clowes there was only criticism from Supreme Commander MacArthur––he criticized Clowes’s handling of the operations at Milne Bay and upbraided him for failing to send back a regular flow of information. Nothing was said of inaccurate information supplied to Clowes by MacArthur and his headquarters.

Many of the differences and misunderstandings that arose, and continued to arise, between the two armies could have been avoided if MacArthur had allowed a senior, battlewise Australian officer on his staff, but this he would not do.

The battle for Milne Bay was applauded by Field Marshal Viscount William Slim, then commanding the British 14th Army in Burma. In his book Defeat into Victory, he stated, “We were helped, too, by a very cheering piece of news that now reached us, and of which, as a morale booster, I made great use. In August-September 1942, Australian troops had at Milne Bay in New Guinea inflicted on the Japanese their first undoubted defeat on land. If the Australians, in conditions very like ours, had done it, so could we. Some may forget that of all the Allies it was Australian soldiers who first broke the spell of the invincibility of the Japanese Army; those of us who were in Burma have cause to remember.”

Earlier at Milne Bay, the militia soldiers of the 7th Brigade, the “chokkos”––chocolate soldiers, a derogatory term used by some AIF veterans to describe a man in a “pretty” uniform who had no intention of doing any real fighting––had had their baptism of fire. Farther to the west, in the “fearful territory” of the Owen Stanley Range of Papua, New Guinea, young soldiers of a smaller militia unit, the 39th Battalion, were undergoing their own baptism of fire on a native footpath that became known as the Kokoda Trail.

Beheadings on Kokoda

On July 21, 1,800 combat troops of the Nankai, the Japanese South Seas Force, landed on the north coast of Papua with supply and base troops and 1,200 natives of Rabaul who would be used as porters and laborers. They came ashore at Gona, a native village and Anglican Mission establishment and hospital.

The combat troops immediately struck inland for Kokoda, an Australian government outpost, airstrip, native village, and a large, privately owned rubber plantation in a valley in the foothills of the Owen Stanley Mountains, about 90 kilometers by air from Gona. The supply and base troops and the Rabaul natives began building bases at Gona and at Buna, a native village and small government outpost a few kilometers along the coast from Gona.

More Japanese landed at Gona and Buna—the total would reach about 13,500—and started a roundup of all Westerners in the area. Some people in hiding at Sangara were betrayed by Papuans to the Japanese; they were beheaded by the sword on Buna beach, among them two Anglican nursing sisters and a seven-year-old boy.

A priest and two sisters from Gona, hiding in the jungle, met up with five Australian soldiers and five American airmen from a crashed plane. They were all betrayed and killed by the Japanese except the priest, Father Benson, who escaped, was recaptured, and sent as a prisoner to Rabaul.

Another mission group of five men, three women, and a six-year-old boy were beheaded one by one, the boy last. Not far away two women from the mission were stood beside open graves and repeatedly bayonetted until they fell dying in the graves.

Ambushing the Japanese

The Japanese combat troops marching on Kokoda took a route that appeared on their maps as a road to Kokoda and on to Port Moresby on the south coast. The road was, in fact, merely a track, a native footpath that began in the malaria-ridden swamps near Gona, went across a plain of up to two-meter high kunai grass and into the foothills of the Owen Stanley Mountains and the valley of Kokoda. Kokoda was 400 meters above sea level and was backed by spectacular mountains 2,000 meters high.

The Japanese combat troops hit their first opposition near Awala when they met 11 Platoon, B Company, 39th (militia) Battalion together with an Australian officer and a few native soldiers of the Paciific Islands Battalion. Hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned, the Australians and native troops retreated across the Kumusi River at Wairopi, where there was a footbridge suspended on a wire cable across the river (the name Wairopi was pidgin for “wire rope”). The retreating Australians destroyed the bridge and ambushed the Japanese as they tried to cross the river.

When the Japanese began to encircle them, the Australians fell back to Gorari, where they were reinforced by 12 Platoon from Kokoda. An ambush was sprung on the Japanese at Gorari Creek, but the Japanese were far too strong and experienced in fighting in this type of country, so the Australians fell back again, to Oivi, where heavy fighting began.

“The Bloody Track”

At 39th Battalion headquarters at Kokoda, Lt. Col. William T. Owen radioed for two more companies of his battalion to be flown in from Port Moresby, and he sent his last platoon to Oivi.

The 39th Battalion, a battalion of militia with little military training, had been digging trenches and building fortifications in and around Port Moresby for several months when it was alerted to move to the north coast to watch for any Japanese landings in the area.

Colonel Owen, with his battalion HQ and B Company, had marched over the Kokoda Trail from Port Moresby and reached Kokoda while others were still struggling along the trail. Next day, 16 Platoon, D Company, limped into Kokoda and half a platoon was flown in in a civilian plane.

From the Port Moresby end, the Kokoda Trail began when, after walking for a mile beside the Goldie River, the footpath went up a steep spur on the Imita Range. Soldiers reached the top of it shocked by the strain of the climb and gasping for air to find this was only the beginning. Before them was range after range of similar topography, the jungle-covered mountains and ranges rising higher and higher and continuing to the far horizon.

To all points of the compass, valleys, crevices, and creases sprayed out at random, many of them filled with mist. There was nothing they could do but stagger on, hour after hour, for distance was not measured in yards and miles but in time––how long to the next staging point, the next rest area, the next camp site?

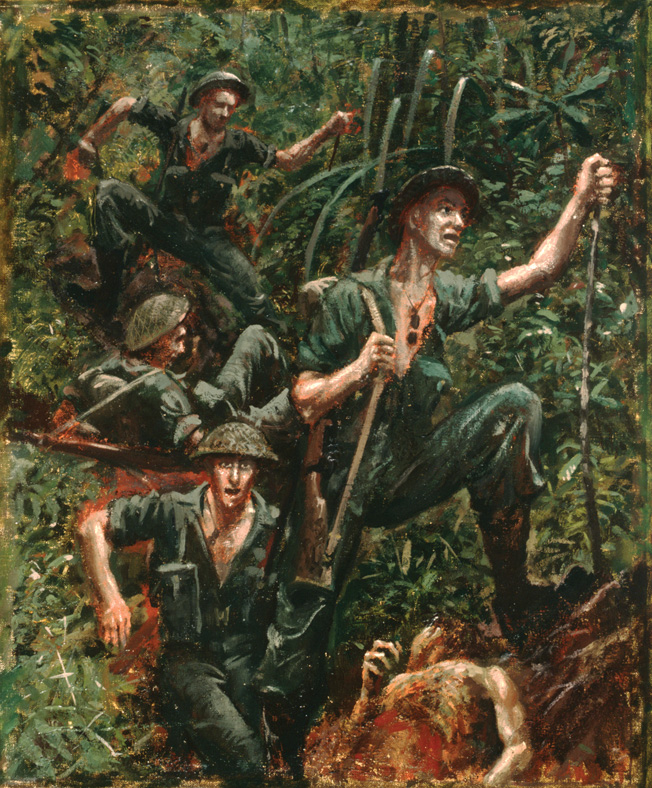

Through it all, roughly northward, poked and prodded the Kokoda Trail, “the bloody track” the Australian soldiers called it. Sometimes gripping the side of a mountain above a raging torrent, sometimes going from rock to rock in a swift-flowing mountain stream, sometimes wading in putrid marsh up to their waists, often going up a slope just a few degrees off vertical and going down a similar bone-jarring, ankle-twisting slope on the other side. There were snakes, spiders, leeches, mosquitoes, insects of all kinds, and constant heavy rain and humidity, eternal slimy mud, freezing cold nights. Diseases soon became rife––dysentery, malaria, typhus, small scratches that quickly became tropical ulcers.

The Fall of Kokoda

At Oivi, a two-hour march from Kokoda, the situation was now desperate. When darkness fell, Captain Sam Templeton, commander of B Company, slipped off into the jungle to find some reinforcements coming from Kokoda and lead them back in. A few minutes later a shot was heard, then silence. Templeton was never seen again.

Convinced they would not be able to withstand the next heavy Japanese attack, the officers decided to abandon Oivi that night. Later, with each soldier holding a webbing strap from the belt of the soldier in front of him and led by the native soldiers, they made their way slowly through the black jungle to reach Kokoda next morning.

Meanwhile, Colonel Owen, with less than 50 men to defend Kokoda, the airstrip, and the trail, had withdrawn to Deniki where a hill provided a strong, natural defensive position. When B Company arrived from Oivi, Owen returned all the troops to Kokoda, signaled Port Moresby that the airstrip was open, and again asked for reinforcements and supplies. But that evening the Japanese sent a mortar bombardment over the Mambare River into Kokoda and, under the covering fire of heavy machine guns, 400 soldiers launched themselves against the Australians.

When the attack was held, the Japanese increased their mortar and machine-gun fire and sent in more troops; the Australians began to fall back to Deniki. Owen, throwing a grenade at Japanese advancing on him through the night mist, was shot in the head. Beside him, Private “Snowy” Parr, a Bren gunner, enraged at the loss of a respected and popular CO, moved off into the night with his “number two,” Private “Rusty” Hollow, looking for vengeance. They found a group of 15 Japanese. Parr opened fire on them with the Bren at close range and wiped them out. Then he and Hollow joined the retreat to Deniki.

Drawing the Japanese Out

In the meantime, C Company had arrived at Deniki and next day A Company came in. Then D and E Companies arrived and with them a replacement CO for Owen, Lt. Col. Alan Cameron. The 39th was now a battalion again, a force of 480 all ranks, and Cameron decided to recapture Kokoda while the Japanese were awaiting reinforcements for the next stage of their assault.

A feint attack on Kokoda and withdrawal to Deniki drew the Japanese out of Kokoda, and their commander, Lt. Col. Tsukamoto, committed his whole force in an attack on Deniki. While the attack was taking place, A and D Companies of the 39th moved behind the Japanese and walked into a deserted Kokoda. They signaled Port Moresby that the airstrip was open again and reinforcements and supplies should be sent at once. They then prepared for the return of the Japanese.

They waited all day but no reinforcements or supplies arrived. At the end of the day the Japanese came back, in torrential rain, and the Australians fought them off through that night and the next day. When night fell, the Australians tied their wounded onto makeshift stretchers and, eight soldiers to a stretcher, carried them away in the darkness across the plateau and up the mountain slopes, the remainder of the two companies close behind them. Next morning the Australians, in the mountains and still within sight of Kokoda, looked back to see two Allied planes dropping supplies on the airstrip.

The Battle of Isurava

The Japanese reurned to Deniki looking for blood. For two days the Australians held them off, then, in danger of being completely cut off, retreated to Isurava and formed a defense perimeter. Lt. Col. Ralph Honner arrived at Isurava with part of the 53rd (AIF) Battalion and Brigadier Selwyn H. Porter, who was in command of all Australians and the few Australian-officered native troops in the area. Total strength was now 45 officers and 584 other ranks.

At this time, Maj. Gen. Tomitaro Horii, commander of the Nankai, arrived with reinforcements at the Gona-Buna beachhead to take command of the assault on Port Moresby. He moved quickly to Kokoda with a fighting force numbering 10,000.

On the morning of August 26, Horii’s battalions overran the outer defenses and swept on in an all-out offensive against Isurava. At the same time the Australians were strengthened by the arrival of one company of the 2/14th (AIF) Battalion; the rest of the battalion was coming over the trail with the 2/16th (AIF) Battalion. These AIF soldiers were veterans of the desert war in North Africa who had returned to Australia and had been sent almost immediately to Port Moresby. At this time, many Australians, in military and civilian life, believed that once the Japanese had taken Port Moresby Australia would be invaded.

The onslaught on Isurava continued through August 27 and 28 with the Japanese trying to outflank the Australians by moving on surrounding jungle-covered slopes. From his headquarters on a mountainside overlooking Isurava, General Horii watched the battle and chafed at this early hold-up of his campaign to take Port Moresby. He ordered up two more battalions and, on the 29th, five battalions began attacking in waves.

The Australians held, breaking each attack. But each attack brought the Japanese closer until some of the Australians were fighting with fists and boots and rifle butts. At one point, Corporal Charles McCallum, bleeding from three wounds, held off the Japanese with a Thompson submachine gun he fired from the shoulder and a Bren gun he fired from the hip. One Japanese soldier came so close he tore an ammunition pouch from McCallum’s chest before the Australian could club him with the Thompson. Australians who were nearby reported McCallum killed at least 40 Japanese in this action.

Not far away, some Japanese soldiers were preparing for another attack. Private Bruce Kingsbury charged in among them with a Bren gun and grenades, scattering them. He then charged one machine-gun post after another, using the Bren and grenades on them, while several of his comrades followed him, killing any Japanese he missed. In the process they forced the Japanese line back 100 meters. Kingsbury, running toward another machine gun, was shot dead by a sniper. For his part in defending battalion headquarters, Kingsbury was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

The Australian Retreat

By evening the weary Australians could hold no longer, and that night some of them withdrew to a ridge behind Isurava. The others withdrew to a few native huts at the village of Alola, where the wounded were being held. Next morning, the Japanese, finding that the Australians had left Isurava, took up their pursuit and began a day of perhaps the heaviest fighting on the Kokoda Trail. In the afternoon the Australians were forced off the ridge and, in a welter of savage fighting, fell back on Alola.

The evacuation of the wounded began. The badly wounded were tied onto stretchers made of tree branches and vines and were carried away on a seven- to eight-day journey in the rain and mud and over some of the roughest country in the world, while the walking wounded began to do so, helping one another as best they could. That night and throughout the next day the remaining Australians fought to hold Alola and give the wounded as much time as possible to move on, but when night came again they were driven out.

They retreated to Eora. At Eora the trail plunged 350 meters on a 45-degree slope to a creek and went up the other side so steeply the soldiers had to climb the slope on hands and knees.

A medical team was in action at Eora, performing surgery on the wounded brought in from the fighting and on passing stretcher cases. Under a thatch roof on which the rain pelted down and on a floor of mud, amputations and treatments were carried out with the aid of flashlights. Exhausted surgeons, doctors, and medical aides worked through the night to clear the worst cases, knowing that the rearguard, with the Japanese close behind, would arrive by dawn.

The last of the Australians straggled in during the night, and they assembled all who could possibly fight and prepared for the attack they knew would come soon. A lieutenant colonel and his headquarters were missing, lost somewhere during the night. The survivors of the 39th Battalion had not had a change of clothing in three weeks; they were ragged, their boots were falling apart, and they were riddled with dysentery and malaria. They had been fighting day and night since before Kokoda, with very little food to sustain them, and were now little more than moving scarecrows.

The stretcher cases were moved out. Among the walking wounded was a soldier with two bullet wounds in one leg and one in his other foot; he moved crab-wise along the trail with others pushing him up the slopes. Another soldier crawled and hopped along––one leg had been blown off below the knee and the stump was ligatured and dressed and wrapped in a rice sack. Another walked along with his shattered arm splinted on a bayonet. Behind them the troops took up positions they knew they would not be able to hold for long.

They held for a day, then retreated to Myola where food and ammunition had been dropped by aircraft. They ate a good meal, destroyed what they couldn’t carry with them, and continued the retreat to Kagi. Here they enjoyed a short respite while the hungry Japanese foraged among the stores left behind at Myola, picking up rice that had been tipped into the mud and punctured cans of meat already mildewed and spoiled. Up to now the Japanese had carried ammunition rather than food, hoping to capture Australian supplies, but the Australians had left very little for them.

The Battle of Ioribaiwa Ridge

The 2/27th (AIF) Battalion arrived at Kagi over the trail from Port Moresby to relieve the 39th Battalion; the remnants of the 39th handed over their automatic weapons and began the long walk to Port Moresby.

The respite at Kagi allowed the Australians the luxury of removing their boots for the first time in 10 days and more; they found their feet, as one described them, “like grotesque, pulpy gloves.” When socks were removed, skin came away with them. Voicing the opinions of the troops was the comment, “Why should we be fighting for country like this? We should be glad to give it to the Jap bastards.”

From Kagi the Australians retreated to the village of Efogi and, from the heights above the village, guided in eight Bostons (Douglas A-20 Havoc bombers) and four Kittyhawks to disrupt Japanese attacks for a few hours. This allowed them time to dig in on the slopes, but Japanese soldiers in ones and twos walked calmly toward them, allowing themselves to be shot dead while disclosing Australian positions to comrades behind them. Then came a bombardment by a mountain gun, mortars, and heavy machine guns, together with assaults that often brought the Japanese to within 15 meters of the Australians before they could be driven back.

Again it was the Japanese tactic of encircling in numbers that forced the Australians out of Efogi. With no positions behind them that could be held against these tactics, the Australians fell back to Menari and then to Nauro, under attack all the way, and then to Ioribaiwa Ridge. At the Ridge, Brigadier Ken Eather’s 25th Brigade of North African veterans was preparing to counterattack and begin pushing the Japanese back. But the Japanese, so close now to their objective, Port Moresby, could hear the sounds of aircraft taking off and landing at the town’s airport, and immediately attacked Ioribaiwa Ridge.

The battle for the ridge continued through September 15 and 16, and Eather and his 25th Brigade, caught up in it, did not have the freedom of movement necessary for him to begin his offensive. He asked for and was given permission to fall back to Imita Ridge across the valley. When the Australians left Ioribaiwa, the Japanese swarmed in, looking for supplies, so intent on finding them that they failed to follow the Australian rearguard; they found very little. Forty hungry Japanese coming down the ridge into the valley were all killed in an Australian ambush.

This was the limit of the Japanese advance. Eather’s patrols now dominated the Uaule Valley between Ioribaiwa Ridge and Imita Ridge four kilometers away.

Horii brought forward 1,000 reinforcements, enlarging his force to two brigades––about 5,000 fighting men––but the reinforcements, like the troops already on the ridge, were starving. The mistake of hoping to capture Australian supplies was being fully driven home. Humanly incapable of going any farther without food and rest, the Japanese dug in on Ioribaiwa Ridge and awaited the fresh reinforcements Horii was promised and with which he intended a final strike through to Port Moresby.

Counterattack on the Kokoda Trail

On September 28, 1942, two Australian 25-pounder field guns smashed holes in the palisades the Japanese had erected on Ioribaiwa Ridge, and the 25th Brigade went in with bayonets and grenades––the counterattack had begun.

Rather than a battle, however, there was only anticlimax. There were no living Japanese, only the dead––hundreds of corpses of soldiers who had fallen and died from wounds and disease and starvation.

Over to the east in the Solomon Islands, the battle for Guadalcanal was raging, and the Japanese high command had decided to give that battle priority over Horii’s thrust to Port Moresby. The reinforcements Horii had been promised were diverted to Guadalcanal, and he was sent a message ordering him to fall back to the Gona-Buna base from which another attack would be launched on Port Moresby when the battle for Guadalcanal was over.

Horii was stunned, as were his officers and men. Japanese soldiers were being told to retreat in the face of the enemy. It was unbelievable. But the message was in the name of the Emperor and Horii dared not disobey it. He began withdrawal at once.

Some of the retreating officers and men fell out to fight to the death rather than retreat any farther. Many wounded and sick stayed behind, with their weapons loaded, hoping to take one or more Australians with them when they died.

The 25th Brigade followed them, moving in three prongs, one in the center on the slimy mud of the Kokoda Trail and the other two in the wet jungle on either side. They scouted every side track, every possibility where the Japanese might have circled to come in behind them. It was time consuming but necessary, for they had heard stories of atrocities from natives who came out of the jungle to meet them.

Some were natives of New Britain the Japanese had brought with them to work as porters and laborers. They told of being worked until jabs from from bayonets could no longer keep them on their feet, then bayonets put an end to some. Villagers along the trail told horrendous stories of bayonetings and shootings and the rape of their women. They found some Australians, here one beheaded, there another tied to a tree and bayoneted.

General Horii’s Last Stand

The 25th pushed on through Nauro and Menari, littered with the rotting corpses and skeletons of Japanese and Australians who had died in the fighting a few weeks before. The stench of death and decay was everywhere. At Templeton’s Crossing on October 8, Horii put up a defense so strong that the Australians thought the enemy had received reinforcements from the Gona-Buna base.

The Australians were held up for six days, and from General MacArthur and others in Australia came accusations they were dragging their feet. It was here they found that, whatever help Horii might have received, it was not food. Diaries and other evidence found on the bodies of Japanese confirmed that some had resorted to cannibalism.

The Australians, like the Japanese going the other way, were soon outrunning their supplies. Each man carried a heavy load, and 800 native porters were employed to carry supplies along the trail, but it was estimated that 3,000 were needed. Some supplies were dropped by aircraft, but the recovery rate was low. And there was the problem of the wounded and chronically sick.

A runway was prepared on a dry lake bed at Myola to evacuate the casualties by air, but requests for aircraft did not result in any arriving. A few pilots did land to show that it could be done, and they took out a handful of the wounded, but those who were left and could possibly move began to walk out. A grim column of 212 battle casualties and 226 sick began the long trek back.

The Japanese retreated from Templeton’s Crossing to Eora Creek to make a stand behind three lines of fortifications built by reserve units with weapon pits bristling with heavy and light machine guns. Stung by accusations of timid tactics from American and Australian commanders in Australia and Port Moresby, the Australians on the trail overran the fortifications, and the advance on Kokoda continued.

When they reached Kokoda on November 2 they found the Japanese had abandoned it and had fallen back to fortifications built at Oivi. Here the Australians used Japanese encircling tactics with small groups meeting and killing each other in the tangled, sodden jungle, and any open space became a killing ground. Exhausted, the Japanese somehow found the strength to counterattack, and the fighting was vicious.

The rate of one Australian killed to two wounded was an indication of the closeness of the fighting. Japanese losses were very heavy, but some escaped the encirclement, only to be hunted down and killed as they tried to cross the Kumusi River. General Horii drowned as a canoe he was in was washed out to sea and overturned 10 kilometers from shore.

The Battle of Gona

The first American troops arrived in Papua on September 12, 1942; they were the 126th and 128th Regiments of Maj. Gen. Edwin F. Harding’s 32nd Infantry Division, and they began to cut a track designed to outflank the Japanese at Kokoda. But by the time of General Horii’s death, Americans, apart from flying air support, had not been used in the campaign.

MacArthur’s communiqués stated that “Allied” troops had won the long campaign for Kokoda and an American press report stated that the announcement of the presence of American infantry in the area “clarified the apparent mystery of the precipitous Japanese retreat across the Owen Stanley Range.”

Hanson Baldwin, the well-known American military journalist, stated in the New York Times that only the intervention of American infantry had saved the Australians from defeat. “American soldiers,” he said, “were rushed into action, and were instrumental in saving the day. With the Australians, they have since given the Japanese a dose of their own medicine, outflanking them and constantly infiltrating into enemy lines until the Japanese are now fighting desperately for their beachhead.”

With the Wairopi Bridge down, the Australian 16th and 25th Brigades crossed the Kumusi over bridges improvised by the engineers and continued down the Kokoda Trail to the coastal swamplands where it all began four months before. Here, with some reinforcements and the Americans, they would face the Japanese in their heavily defended base at Gona, Buna, and Sanananda.

Plans for the attack on Buna had already been made at MacArthur’s headquarters. The Australian 16th and 25th Brigades would press on to Buna, a battalion of the American 126th Regiment would march through Jaure and attack from the south, and the rest of the 126th plus the 128th Regiment would fly to Wanigela and Pongani and attack from there. By the time the Australians had crossed the Kumusi, the Americans were moving on Buna in three separate columns, supported by Australian commandos and artillery.

The Japanese had bounced back from their defeat and were turning their beachhead into a bastion that would maintain their tiny hold on Papua. With reinforcements, they now had some 9,000 troops in the beachhead, and Lt. Gen. Hatazo Adachi of the 18th Army was in overall command of Papua-New Guinea operations.

On the morning of November 19, advance elements of Brigadier Eather’s 25th Brigade ran into Japanese positions just south of Gona village. Behind the positions were strong defenses. The Australians attacked the defenses and gained some ground but were forced to retire next day with heavy casualties. The brigade, reduced to 736 mostly sick and tired troops, lost another 204 killed and wounded in the assault.

They were reinforced by Brigadier Ivan N. Dougherty and his 21st Brigade, veterans of the campaigns in Libya, Greece, and Crete, and now located between Kokoda and Ioribaiwa. Doughherty took responsibility for the Gona area. He quickly engaged his brigade in offensive operations and, although his first attacks failed, a series of grinding assaults blasted the Japanese out of their defenses; the village of Gona was occupied on December 9. The Japanese garrison of 800-900 was almost entirely wiped out; the brigade buried 600 of their dead.

I want you to take Buna, or not come back alive

The Australian operations had secured the left flank of the advance, but along the Sanananda Track and at Buna the advance had become confused and stalemated. The American 126th and 128th Regiments, advancing along two coastal trails from the south toward Buna, met only isolated resistence as they approached the main Japanese lines, but resistance soon hardened.

MacArthur, intent on his Americans speeding up the campaign, instructed the Australian commander, General Thomas Blamey, that his land forces must attack the Buna-Gona area on November 21, saying: “All columns will be driven through to objectives regardless of losses.”

Harding launched his division into the offensive on the morning of November 21, and for the next nine days there was great confusion. The troops, badly led, poorly trained, and conditioned to a soft life prior to their arrival in Papua, were badly mauled in their first attacks on the main Buna defenses.

MacArthur, disappointed, sent for Lt. Gen. Robert Eichelberger, commander of the American I Corps; he arrived at MacArthur’s temporary headquarters in Port Moresby on November 30. MacArthur told him, “Bob, I’m putting you in command at Buna. Relieve Harding. I want you to remove all officers who won’t fight. Relieve regimental and battalion commanders if necessary. Put sergeants in charge of battalions and corporals in charge of companies––anyone who will fight…. I want you to take Buna, or not come back alive, and that goes for your Chief of Staff too. Do you understand?”

“Yes, sir.”

The Battle of Buna

Eichelberger arrived at Buna the next day and was appalled by what he found. The command structure was chaotic, the morale of the troops was low, and “a general malaise hung over the whole operation.” He immediately relieved Harding and two regimental commanders and replaced them with members of his own staff. He ordered an attack to be launched with Australian Bren gun carriers in support on December 5.

The attack was launched on two fronts, one against Buna village, the other against the strong defenses east of the village along the airstrip known as New Strip. Some success was achieved in the village area but the main garrison held firm and the airstrip defenses could not be cracked despite heavier American attacks. By December 10 the Yanks had lost 1,827 men killed, wounded, missing, and sick, and Eichelberger relieved the 126th Regiment with the 127th.

The fresh 127th entered Buna village to find the remnants of the garrison gone but the airstrip defenses still holding, and Eichelberger prepared for another assault. He was then advised that Brigadier Wootten’s 18th Australian Brigade was coming into the line to take over responsibility for the airstrip sector. The brigade would have with it two highly trained troops of Stuart light tanks of the 2/16th Armored Regiment.

Wootten took over the command, including three American battalions, on December 17. His intention was to capture the Cape Endaiadere-New Strip-Old Strip-Buna government headquarters region.

The first objective was the whole coastal area between New Strip and the mouth of Simemi Creek, where the Japanese were entrenched in a series of powerful strongpoints. Each was a small fortress concealed and camouflaged, some protected by interlaced coconut logs covered with six feet of earth, some steel roofed, others concrete.

Wootten’s assault began at 7 am on December 18, with the Australians spearheading the operation behind seven tanks. “Their extraordinary courage as they walked forward into a torrent of fire and disposed of one strongpoint after another captured the imagination of the Americans,” General Eichelberger wrote after the war. “It was a spectacular and dramatic assault, and a brave one. From New Strip to the sea was about a mile. American troops wheeled to the west in support, and other Americans were assigned to mopping-up duties. But behind the tanks went the fresh and jaunty Aussie veterans … with their blazing Tommy guns swinging before them.

“Concealed Japanese positions, which were even more formidable than our patrols had indicated, burst into flame. There was the greasy smell of tracer fire, and heavy machine gun fire from barricades and entrenchments. Steadily tanks and infantrymen advanced through the sparse, high coconut trees, seemingly impervious to the heavy opposition.”

By the end of the first day the Australians had cleared the Japanese from their positions on a line that ran from the sea due south to the east end of New Strip, despite having lost about one third of their attacking strength. But Wootten maintained the momentum of his operations, and each day brought further gains despite the depth of the Japanese defenses.

A U.S.-Australian Victory at Buna

By January 1, 1943, the three battalions of the brigade had reached Giropa Point. They had suffered 863 casualties, 45 percent of their total strength. In the final count of the battle for Buna, almost the whole of the American 32nd Division had become involved, and the total Allied losses amounted to some 2,870 battle casualties. Of these, the Australians suffered 913. Known Japanese losses were 900 killed by the Australian 18th Brigade east of Giropa Point and 490 in the village and local government headquarters. How many more were killed is not known.

Some American and British historians claim Buna a victory for U.S. forces, but credit for the victory should at least be shared with the Australians. Anxious as the Americans were to obtain a quick and decisive result in their own right, it was the intervention of Wootten’s troops that broke the back of the Japanese defenses on the coast.

Striking the Sanananda Track

With the left and right flanks of the Allied advance to the coast now secure, attention was concentrated on Sanananda, where the Japanese had established their main defensive positions astride the Sanananda Track in terrain that was a mixture of heavy swamp, kunai grass, and thick bush.

From mid-November to mid-December 1942, the Japanese garrison of some 6,000 troops had stubbornly held off attacks by the 16th Australian Brigade, a brigade in the last stages of physical endurance after its long and arduous fight over the Owen Stanley Mountains. When they were pulled out of the line in December, the brigade’s fighting strength was reduced to 50 officers and 488 other ranks.

The troops of the U.S. 126th Infantry Regiment who relieved them were fresh and full of confidence. They told the Australians, “You can go home now. We’re here to clean things up.” But this confident spirit was soon broken by the malarial swamps and the savage Japanese resistance. They were relieved by two Australian militia battalions of the 30th Brigade, but the battalions’ heavy attacks achieved only limited success, and Maj. Gen. George Vasey reluctantly decided he would have to wait until Buna had been eliminated before finishing the fight at Sanananda.

When Buna was eliminated, it was decided that Australian forces would attack Sanananda frontally from along the Sanananda Track, while the Americans moved on Sanananda along the coast from Buna. Brigadier Wootten’s 18th Brigade would spearhead the attack.

Wootten attacked on the morning of January 12, sending two battalions in a flanking movement against the Japanese defenses. This resulted in a long day of murderous fighting in steaming heat and foul swamplands. By nightfall it seemed that the attack was going to fail, but early next morning a Japanese soldier was captured. He revealed that all fit Japanese troops had been ordered to withdraw, leaving only the sick and wounded to defend the strongpoints. Wootten immediately attacked.

By nightfall on January 14, the 18th had captured the road junction that had delayed the advance for so long, and Australian and American troops continued attacking the remaining defensive positions until all organized resistance ceased on January 22.

Japan’s First Defeat on Land

The defense of Sanananda was another demonstration of the extraordinary tenacity of the Japanese soldiers. They lost some 1,600 killed and 1,200 wounded in defending the swamp surrounding Sanananda, held up the Allied advance for two months, and inflicted heavy casualties on the Australians––600 killed and 800 wounded––and the Americans––274 killed and about 400 wounded. The toll of sickness in both armies was greater than these figures.

The ending of the Sanananda operations completed the first defeat of a Japanese land force during World War II. About 20,000 soldiers were in action in the Kokoda, Milne Bay, and Buna-Gona operations, and it is known that more than 13,000 of them perished in various ways. About 2,000 were evacuated by sea, and some relative few escaped from the battle areas to join comrades elsewhere. However, most of the remaining Japanese died of wounds, disease, and starvation, leaving their bones in the mountains, swamps, and jungles of Papua.

The Australians, who had borne the lion’s share of the fighting, suffered 5,689 battle casualties between July 22, 1942, and January 22, 1943, and the Americans, during their involvement in the Buna and Sanananda sector, lost 2,931.

Invaluable Experience For the Australian Army

During the fighting in Papua, the Australian Army developed techniques of tactical leadership that were very useful in later fighting in New Guinea and by the British in Burma. The Australian soldier became expert in jungle warfare––at least the equal or even better than Japanese soldiers who had established an almost superhuman reputation.

Whether the savage fighting and heavy casualties suffered in the final stages of the campaign, especially at Buna, Gona, and Sanananda, were strategically justified is open to question. Perhaps the Japanese garrisons could have been isolated and left to wither on the vine or to be overwhelmed by superior forces—a strategy MacArthur adopted later in the New Guinea campaign.

In any event, the victory in Papua gave a boost to Allied morale. It also destroyed any chance of the Japanese invading Australia, although the Japanese high command was coming to the conclusion that the invasion, capture, and garrisoning of such a huge country was well beyond their resources.

And, importantly, as Field Marshal Slim pointed out, the Australians “broke the spell of the invincibility of the Japanese army.”

Great read.

One thing to clarify – the completely untrained Aussie militia were derided as ‘chocolate soldiers” because they were expected to melt under pressure.

Clearly they did anything but.

Hi John

I found your article very interesting. Could you please email me directly as I would like to discuss some photographic research I am doing on Buna.

thanks Juanita

Thanks John. Incredible story of Aussie guts and valor. For too

long MacArthur took credit for the sacrifices of our Southern Cross

comrades. Good show.

Wonderfully written. Reinforces my belief MacArthur was a egitistical bully. God bless the individual foot soldier no matter the rank or unit!

Read Ghost Division for an accurate account of American troops action in the campaign.