By John Walker

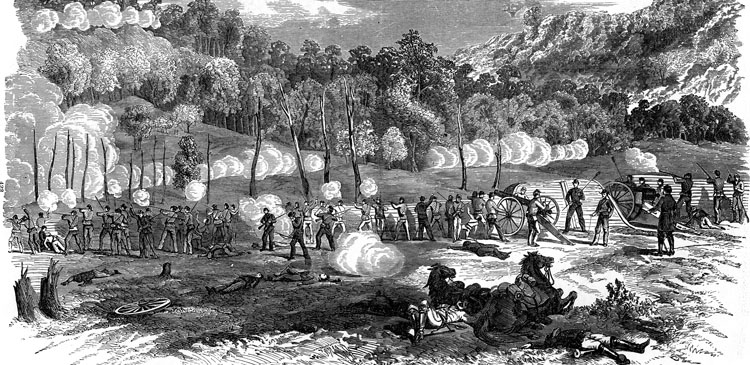

Shortly after dawn on June 27, 1864, Union artillery crews sprang into action on 200 guns facing miles of the Confederate defenses along the Kennesaw Line near Marietta, Georgia.

Jostled and jarred awake by the tremendous barrage, Private Sam Watkins and his fellow riflemen of the 1st/27th Tennessee Regiment (Consolidated) stood up in their trenches and watched, enthralled as hundreds of Yankees surged toward them from the Federal lines 400 yards away.

Although the concentrated shelling did little more than alert the defenders that a ground attack was imminent, the Confederates marveled at the volume and intensity of the fire. To them it was one more manifestation of Yankee wealth and ingenuity. “All at once a hundred guns from the Federal line opened upon us, and for more than an hour they poured their solid and chain shot, grape and shrapnel right upon this … point,” wrote Watkins. For the next three hours one tightly packed Federal column after another charged into the teeth of the Confederate rifle fire.

The stakes that day could not have been higher. After his advance into north Georgia had stalled in the rain and mud just 20 miles from Atlanta, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman had decided to launch an all-out frontal assault against the entrenched positions of General Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederate Army of Tennessee in the hope of bringing the campaign to a rapid, decisive end. A Union breakthrough in strength somewhere along the line would split Johnston’s army, lead to the capture of Marietta and a Yankee drive to the Chattahoochee River, and ultimately to the capture of Atlanta. Such a string of events would prove catastrophic to the Confederacy and might result in the South’s surrender. For these reasons, the Kennesaw Line had to be held “at all hazards,” according to Johnston and his lieutenants.

Sherman’s Three Armies

In March 1864, the American Civil War neared its fourth year, and newly promoted Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant prepared to head east to Washington to assume his duties as general-in-chief of all Union armies. Grant chose Sherman to succeed him as commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi, a sprawling swath of territory that encompassed most of the war’s western theater. Grant’s instructions to his fellow Ohioan for the coming campaign were straightforward. Sherman was to move south from Chattanooga, Tennessee, along the Western and Atlantic Railroad and not only destroy Johnston’s army, but also systematically demolish the enemy’s industrial capability.

The irascible Sherman began his advance into Georgia on May 4 with an army group numbering 98,000 men against Johnston’s 49,000. But the terrain favored the Southerners, for behind Johnston lay 100 miles of mountain ranges, rivers, and tangled forests. It was ground that would prove a formidable ally to the Confederate defenders.

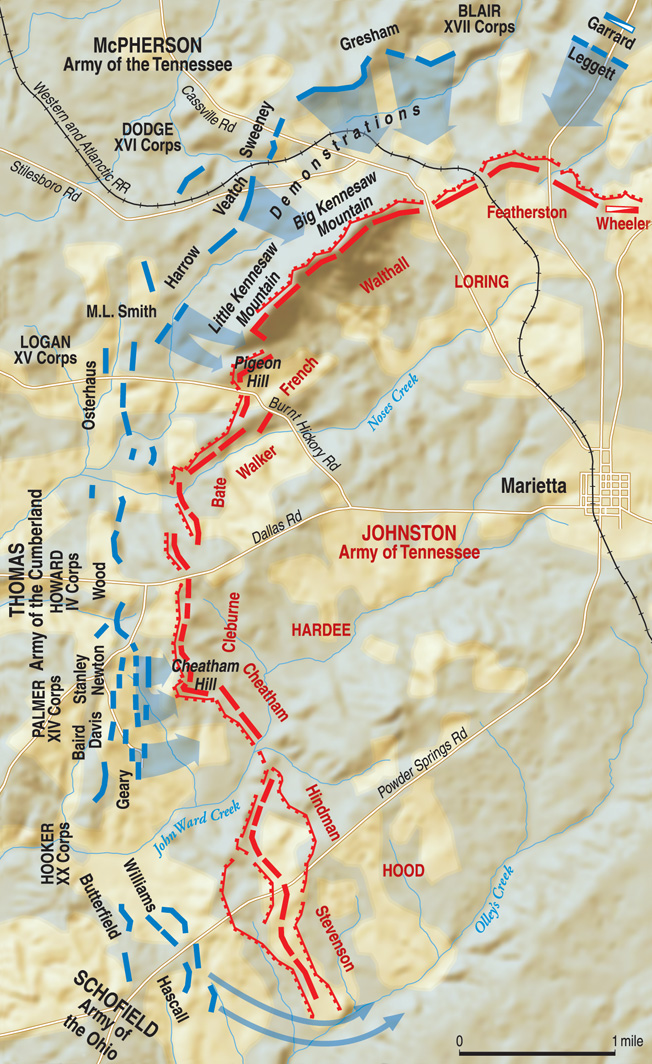

Sherman’s invasion force consisted of three armies: 60,000 men of Maj. Gen. George Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland, 25,000 men of Maj. Gen. James McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee, and 13,000 men of Maj. Gen. John Schofield’s Army of the Ohio.

Stalemate

Johnston’s Army of Tennessee during the Atlanta Campaign consisted of Lt. Gen. William Hardee’s corps, Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood’s corps, and Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry corps. When Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk’s 16,000-man Army of Mississippi joined Johnston’s army in May, it raised the number of Johnston’s troops to 65,000 men.

Johnston had established a strong position west of Dalton on Rocky Face Ridge astride the Western and Atlantic Railroad 25 miles south of Chattanooga, where he awaited the Federal advance. Sherman responded by commencing a series of flanking movements that resulted in Johnston withdrawing to Resaca on May 12. After two days of hard fighting near Resaca, Johnston withdrew south to Cassville on May 15 to avoid being outflanked.

Believing he had an opportunity to strike Sherman a telling blow, Johnston ordered a major attack at Cassville on May 19. Johnston’s plan called for Polk’s corps to draw the Union forces toward them so that Hood’s corps could strike them in the flank. But the usually aggressive Hood, alarmed by an erroneous report that a strong enemy force had unexpectedly gained his flank, pulled back and called off his attack. Afterward, Johnston fell back 10 miles to a new line south of the Etowah River. The Confederates established a new defensive position around Allatoona Pass.

Johnston had no luck against the Yankees at Allatoona either. But Sherman was not about to launch a frontal assault on an entrenched enemy in a heavily fortified mountaintop position. At that point, Sherman decided to move away from the railroad line along which he had been advancing. Although he was stretching his supply line by moving away from the railroad, he nevertheless proceeded with the change in tactics. On March 22 he ordered his three armies to march west. Johnston matched his move and redeployed his troops south of Dallas. The Confederate line stretched four miles from Dallas to New Hope.

After sharp fighting at New Hope Church, Pickett’s Mill, and Dallas over the course of several days beginning on May 25, both armies remained stationary as weeks of torrential rain transformed Georgia’s red clay roads into muddy quagmires. While senior commanders on both sides discussed strategy, the frontline troops skirmished and harassed each other with artillery and sniper fire on a daily basis.

Hood’s Disaster at Kolb’s Farm

Meanwhile, Confederate President Jefferson Davis grew restive over Johnston’s strategy of trading territory for time. On the northern side, Sherman became increasingly concerned about the deteriorating tactical situation. He believed all three of his armies were in danger of losing their fighting edge. “My chief source of trouble is with the Army of the Cumberland, which is dreadfully slow,” he told Grant in mid-June. “A fresh furrow in a plowed field will stop the whole column, and all begin to entrench.” He explained to Grant that despite his best efforts some of his senior commanders, particularly Army of the Cumberland commander Maj. Gen. George Thomas, were reluctant to press that attack despite repeated admonishment.

The two armies gradually shifted their lines eastward until both were astride the railroad just north and west of Marietta. Fearing envelopment, on June 19 Johnston withdrew his army into prepared entrenchments along Big Kennesaw Mountain and its spurs, where pioneers working around the clock digging trenches and erecting fortifications had converted the works into an earthen fortress.

After judging the Kennesaw Line too formidable to take by direct assault, which ironically he would try to do a few days later, Sherman sent Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s 15,000-man XX Corps to probe Johnston’s left flank south of Powder Springs Road. Johnston countered by pulling Hood’s corps out of line and sending it south and west along Powder Springs Road to extend the Confederate left flank. Hood, who commanded 14,000 men, was in position by June 22. In the mistaken notion that he had outflanked a Union flanking force, Hood impetuously attacked Hooker that afternoon near Peter Kolb’s farm without reconnoitering the area. The Yankees repulsed the Confederates, inflicting more than 1,000 casualties on Hood, more than three times the number suffered by the Yankees, in just a few hours of fighting.

“It May Cost Us Dear”

With his troops requiring 65 rail cars of supplies each day, Sherman fretted over his single-track lifeline. A significant interruption to his long supply line might cripple his campaign. With another turning movement on the muddy roads seemingly impossible, Sherman also feared Johnston might take advantage of the stalemate to dispatch troops to reinforce General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Sherman was infuriated when he learned that his detractors had deemed him as someone who was not a hard fighter, and he decided to refute the charge once and for all.

Sherman believed Johnston was anticipating another turning movement and that the Confederate commander had thinned his line in response to flank probes. “I am now inclined to feign with both flanks and assault the center,” Sherman told U.S. Army Chief of Staff Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck on June 16. “It may cost us dear but the results would surpass an attempt to pass around.”

For that reason, on June 24 Sherman issued a special field order directing his three army commanders to reconnoiter the Confederate positions to their front in force at 8 am on June 27. To minimize the cost if the offensive failed, Sherman limited the weight of the assault to less than a fifth of the troops on hand and, giving up the element of surprise, ordered an hour-long artillery barrage to precede the attack.

Neither of Sherman’s two primary attacks was directed against Confederate forces on Big Kennesaw proper, although McPherson was to demonstrate against it to keep Johnston guessing as to the true location of Sherman’s main attack. Sherman assigned the heaviest assaults to Thomas, who Sherman instructed to attack the Confederates at any point near the center of their line using his own judgment. Sherman also directed Schofield to conduct a limited attack against Hood’s corps on the Confederate left to confuse Johnston as to where the primary attack would fall.

After Sherman and Schofield reconnoitered Hood’s heavily fortified two-mile front on the morning of June 25, Sherman modified the order for the attack against the Confederate extreme left flank. Schofield and Hooker would instead feint against Hood’s line on the following morning while Brig. Gen. Jacob Cox led his division down Sandtown Road and attempted to establish a foothold on the east side of Olley’s Creek.

Sherman hoped this would compel Johnston to shift troops from his center to his left, thereby weakening his center and making it vulnerable to a breakthrough on June 27. As it happened, one of Cox’s brigades, which was commanded by Colonel Robert Byrd, crossed the creek on June 26 and seized a hill on good defensive ground. In so doing, Byrd had actually turned Johnston’s left flank, but the achievement went largely unnoticed. Because he was short on manpower, Johnston made no attempt to dislodge Byrd’s brigade. Schofield, therefore, was free to exploit the unexpected opportunity on the day scheduled for the main attack.

The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain Begins

After a brief preparatory artillery barrage, McPherson’s skirmishers pushed up the steep slopes of Big Kennesaw at 8:30 am on June 27. Their objective was to keep Johnston from shifting troops from there to other parts of the field. Brig. Gen. Mortimer Leggett and Brig. Gen. Walter Gresham’s XVII Corps skirmishers here confronted the Rebel defenders of Maj. Gen. William Loring’s corps.

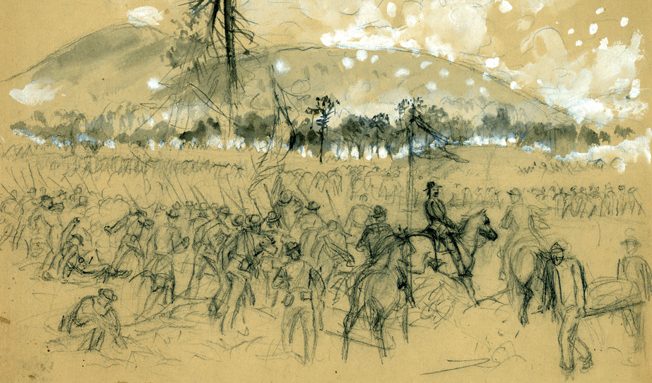

Loring had assumed command of Polk’s corps after its commander was killed by an artillery shell on June 14 while observing Union troop positions from atop Pine Mountain. The lack of underbrush and forest growth meant the defenders could see nearly every movement of the Federals as they left their works. For the Confederates, the attack was a magnificent sight. “Presently, and as if by magic, there sprung from the earth a host of men, and in one long, waving line of blue the infantry advanced,” wrote Confederate Maj. Gen. Samuel G. French, whose men were stationed opposite McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee. Caught in a maelstrom of cannon and rifle fire, McPherson’s Yankees making the demonstration on the Union left halted after a couple of hours, suffering approximately 400 casualties.

To the right of McPherson’s army, three brigades from Maj. Gen. John Logan’s XV Corps of the Army of the Tennessee attacked east on a wide front. On the ridges of Little Kennesaw and Pigeon Hill, the Confederate brigades of Colonel William Barry and Brig. Gen. Francis Cockrell waited, their lines bent toward each other. The Confederates were positioned in this sector to pour a deadly crossfire into any Yankee regiments that dared to enter the wooded slopes between Little Kennesaw and Pigeon Hill.

On Logan’s left, Colonel Charles Walcutt deployed the 46th Ohio in front in a skirmish line, followed by the 103rd Illinois and 6th Iowa in a first line of battle and the 40th Illinois and 97th Indiana in the second. Stepping off shortly after 8 am, the 46th Ohio’s skirmishers struck the picket line 200 yards from the crest of Little Kennesaw, surprising and capturing a large number of Rebel skirmishers, then rushed toward the southern slopes of Little Kennesaw.

The men of the 6th Iowa and 103rd Illinois to their rear were struggling desperately in the dense undergrowth. Walking upright was hardly possible in the tangled vines, and the battle lines quickly unraveled in the dense vegetation. As the two rearward regiments came up, all five regiments merged into one confused mass of men. The men of the 40th Illinois on the left flank of Logan’s attack got to within yards of Barry’s trenchline on the rugged slopes of Little Kennesaw before falling back.

To Walcutt’s right, Brig. Gen. Giles Smith’s men were deployed opposite Cockrell’s Missouri brigade. Although stretched thin behind their rock and dirt earthworks, the Missourians enjoyed excellent protection from the attackers’ fire. They lay their rifle barrels on the top of their breastworks and picked off the Yankees as they came on.

Missouri vs Missouri

After forming his brigade into a front three regiments wide and two deep, his right flank anchored on Burnt Hickory Road, Smith led his men forward through dense forest and vegetation, struck Cockrell’s skirmish line, and drove it back. After pausing to dress their lines, the Yankees rushed up the slope.

Cockrell’s Missouri Confederates were fighting against Union troops from their own state (the Union’s 6th and 8th Missouri Regiments of Smith’s brigade). “Our infantry did not return their rammers as usual, after loading, but stuck them in the ground and snatched them up when wanted, to save time,” wrote Lieutenant Joseph Boyce of the Confederate 1st Missouri Infantry, who found it sickening to fight against fellow Missourians. “No troops could stand such a concentrated fire long.” Realizing the assault was futile, Union 2nd Division commander Brig. Gen Morgan Smith (who was Giles Smith’s older brother) ordered the attacking units to fall back.

An hour into Logan’s attack, Cockrell requested reinforcements from French on Little Kennesaw to the north. French sent two groups of reinforcements, and he personally led the second group into battle. “So severe and continuous was the cannonading that the volleys of musketry could scarcely be heard at all on the line,” wrote French.

Colonel Americus Rice’s 57th Ohio made it far enough up the slopes to engage Colonel James McCown’s 3rd/5th Missouri Regiment (Consolidated) at close range. But the Ohioans could only stand the withering fire from their entrenched foe for about 15 minutes before withdrawing down the slope. During the clash, Rice was struck by Rebel fire in the right leg, left foot, and the forehead.

“The assaulting column had struck Cockrell’s works near the center, recoiled under the fire, swung around into a steep valley where, exposed to the fire of the Missourians in front and right flank and of Sears’ men on the left, it seemed to melt away or sink to the earth to rise no more,” wrote French, who observed the attack.

Lightburn Repulsed

On Giles Smith’s right flank just south of Burnt Hickory Road, the Yankees of Brig. Gen. Joseph Lightburn’s brigade formed into two lines, each of which consisted of three regiments. They surged forward against the right wing of Maj. Gen. William Walker’s division, held by Brig. Gen. Hugh Mercer’s four Georgia regiments.

Six companies of the inexperienced 63rd Georgia were posted in Mercer’s front as skirmishers. After serving mainly as garrison troops on the Atlantic Coast, the Georgians had joined Johnston’s army six weeks earlier and were eager to prove themselves in battle after Hardee’s veterans derided them as “holiday soldiers.” When Lightburn’s men moved out, the wooded, uneven terrain quickly disordered their battle lines and slowed the advance.

Lightburn’s men finally struck the Confederate picket line, and desperate hand-to-hand fighting erupted. Men on both sides fought with bayonets and clubbed muskets. After suffering 80 casualties, the Georgians fell back. Lightburn’s troops pursued them through the open fields southwest of Pigeon Hill. With clear fields of fire, Mercer’s Georgians poured heavy fire into the Union ranks and checked the advance. Afterward, Lightburn’s men redirected their fire at Cockrell’s reformed skirmish line, forcing the Missourians to retire. At that point, French ordered three Rebel guns atop the crest to blast Lightburn’s advancing troops. With shells from Pigeon Hill and musket balls from both sides of Burnt Hickory Road raining down on the survivors, Lightburn’s Yankees were driven back.

Skirmishers from Brig. Gen. Peter Osterhaus’s division moved forward on Lightburn’s right to support Logan’s attack. Much like their fellow Yankees to the north, though, these men came under galling artillery and musket fire that halted their assault.

“When our defeated line came back over the breastworks, I saw a brave color bearer marching erect with his teeth set, and the pallor of death spread over his face,” wrote Major Charles Dana Miller of the 76th Ohio Regiment, who participated in the attack. “In his left hand was gripped the flag of the regiment, which he was carrying to a place of safety, while his right arm was shot away with the blood streaming from the ragged stump. He held the colors erect until they reached their former position, then laid down and died.”

By 11 am Logan’s entire attack against Little Kennesaw and Pigeon Hill had been repulsed. The three assaulting brigades suffered a combined loss of nearly 600 men. They had nothing to show for their effort.

“Swept by Discharges of Grape and Canister”

Thomas’s main offensive in the Union center got underway around 9:30 am. Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard instructed Brig. Gen. John Newton to send three of his four brigades against the ridgeline in front of them, which became known thereafter as Cheatham Hill after Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham, who commanded the troops in that sector. Howard told Newton to deploy the brigades of Brig. Gens. Charles Harker, George Wagner, and Nathan Kimball with their men in columns with the regiments of each brigade lining up one behind the other. His intent was that the columns would be able to punch through the Rebel works.

Wagner and Harker prepared to advance behind a skirmish line from Colonel William Grose’s brigade of Maj. Gen. David Stanley’s division. Newton withheld Kimball’s brigade as a reserve to be deployed as needed as the attack unfolded. Newton’s Yankees were opposed by Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s veteran troops, as well as part of Cheatham’s division to the south. Cleburne’s defenders had erected an imposing array of obstacles in front of their position. The attacking force would have to traverse a branch of John Ward Creek, push through the tangled undergrowth, and confront a line of felled trees and sharpened stakes known as chevaux de frise.

No sooner had Newton’s Yankees emerged from the protection of their lines than the Confederates opened up with all of their artillery and musketry in that sector. The Yankees were struck with shot, shell, and musket balls. Cleburne and his veterans were hard fighters, and they were not about to make it easy for the attacking Yankees.

Leaving a trail of dead and wounded in their wake, Wagner’s men finally reached the obstacles in front of Cleburne’s line. They attempted in vain to clear the impediments from their path. Color bearer Henry Shedd of the 26th Ohio, whose regimental flag received 56 bullet holes during the course of the assault, wrote afterward that he believed Wagner’s brigade got to within about 20 yards of the works before the advance ended. As his men went to ground, Wagner received word that Kimball’s brigade would be coming up soon on his left.

With the 36th Illinois out in front as skirmishers, Kimball’s six other regiments pushed forward into the same difficult terrain and obstructions that were crippling Wagner’s attack. The attack was “swept by discharges of grape and canister,” wrote Lt. Col. Porter Olson of the 36th Illinois, adding that the Confederates’ strong earthworks and heavy infantry fire made carrying Cleburne’s works seem like an impossible task.

After two long hours spent struggling through a field under heavy fire, Kimball’s men could go no farther. Logan ordered Kimball to pull his men back to the main Union line, in itself a daunting proposition. “The slaughter among our troops at this moment was even greater than when they advanced for the enemy now rose from behind their works, fearless of danger from the retreating force, and fired with greater precision than when the column advanced,” wrote Sergeant John Marshall of the 97th Ohio of Wagner’s brigade.

“Boys, This is Butchery”

To the right of Kimball and Wagner, Harker and his troops were enduring their own ordeal. Harker, who was just 26 years old, had turned down a request to serve as Howard’s chief of staff, a position that would have sheltered him from the dangers of battlefield command. An injury he had suffered weeks earlier made it difficult for him to walk, so Harker rode into battle on a white horse, which made him a conspicuous target.

Harker led seven regiments, all of which were arrayed in column, forward toward the Confederate lines. They advanced behind a screen of skirmishers from Colonel Emerson Opdycke’s 125th Ohio. Opdycke led his skirmishers forward and captured a good number of their Confederate counterparts. Harker’s columns also made good progress. As they neared Cleburne’s works, only 600 yards from the Federal lines in this sector, Rebel gunners depressed the muzzles of their 12-pounders to almost fully horizontal and switched from shell to canister ammunition. The lethal canister rounds struck wooden stakes and other obstructions in front of the trenches, sending shards of wood and other debris, as well as clouds of lead balls, into the oncoming Yankees.

Seeing his line faltering, Harker rode forward, raised his hat, and called for his men to follow his lead and carry the enemy’s works. When he was within 10 yards of the trenchline, a musket ball struck his arm and passed into his chest. He tumbled from his horse mortally wounded. The loss of Harker, as well as steadily mounting casualties, halted the attack. Command of Harker’s brigade devolved to Colonel Luther Bradley of the 51st Illinois. Shortly after he assumed command, he received orders to pull back.

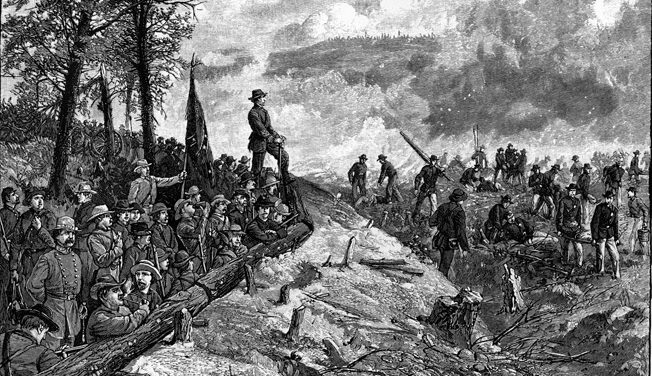

When the ground to the Confederate front in this sector caught fire from muzzle flashes and bursting shells, putting many of the wounded Federals at risk of burning to death, Colonel William Martin of the 1st/15th Arkansas Regiment (Consolidated) stood atop the parapet and raised a white handkerchief to signal a halt to the fighting. “Boys, this is butchery,” he shouted. After Martin’s offer of a brief ceasefire to allow the attackers to remove their wounded was accepted, Yankees and Rebels alike went to work to move the fallen out of harm’s way. A Union officer then handed Martin a pair of pearl-handled pistols as a token of appreciation. Cleburne’s line was never seriously threatened at any point by the attack of Newton’s division, which lost more than 650 men in three hours.

The Defense of Cheatham Hill

By the morning of June 27, the Rebels of Cheatham’s division had held their positions on Cleburne’s left flank for a week during which they had endured searing heat, artillery bombardment, and sniper fire. Cheatham had deployed Brig. Gen. Alfred Vaughn’s brigade on the same ridge that Cleburne’s men held on June 19, then extended Vaughn’s line with the rest of his division on the night of June 20. Because that ridge ended on a low hill next to a branch of John Ward Creek, the only suitable defensive ground for the rest of Cheatham’s division was located farther to the east. Deployed on Vaughn’s immediate left, Brig. Gen. George Maney had to bend back his own line. He placed one regiment on the southern edge of the hill facing west toward the Union position and then put his other regiments facing south. This created what became known as the Dead Angle.

Toiling in the dark, Cheatham’s engineers had mistakenly established the main trench line 50 yards too far up the hill, which meant that many of the defenders on the hilltop could not see all of the ground to their front. Four companies of the 1st/27th Tennessee Regiment (Consolidated) totaling 180 men held the section of the Dead Angle facing west, while Maney’s other Tennessee regiments faced southward. Eight concealed artillery pieces were arrayed just south of the angle and two more to the north, all positioned to enfilade any Union troops attacking the angle. Union artillery had blasted away some of the head logs on the Confederate trenches at the Dead Angle, which meant that the Rebels were not as well protected as some other parts of the Confederate line.

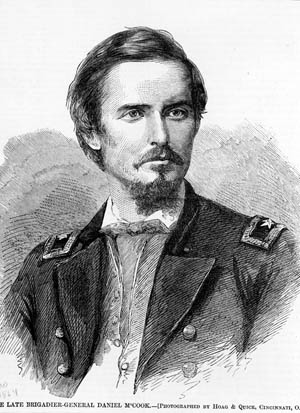

Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis, one of the division commanders in the Union XIV Corps, ordered two of his three brigades to assault Maney’s position. Like other Union assaults that morning, Davis hoped to overwhelm the Rebel works quickly by attacking in dense columns of regiments rather than in traditional long, thin lines. Having received their orders, Colonel Daniel McCook and Colonel John Mitchell formed their troops for the assault.

In addition to their breastworks, Cheatham’s Rebels benefited from infantry obstacles in front of their position, such as rows of sharpened stakes known as abatis, and also artillery unseen by the enemy that fired deadly canister at close range into the oncoming blue ranks. Despite these enhancements to their defense, Cheatham’s outnumbered defenders were hard pressed to prevent being overrun by the rushing Yankee tide; however, they rose to the task

“No sooner would a regiment mount our works than they were shot down or surrendered, and soon we had every gopher hole full of Federal prisoners,” wrote Watkins. “Yet still the Yankees came. It seemed impossible to check the onslaught.”

With the leading regiments of the attacking brigades slowed by stout Rebel resistance, those to the rear soon pushed to the front. As they advanced, Union soldiers leaned forward as if moving into a fierce wind or rainstorm. Slowed by the dense undergrowth and abatis on the slopes of Cheatham Hill, the blue line withered under the heavy fire.

Caught Between Two Fires

On Vaughn’s right, a pair of 12-pounders enfiladed the left flank of McCook’s brigade, leaving the ground littered with dead and wounded Federals. On the other end of the Confederate line in that sector, two batteries pummeled McCook’s right flank and fired directly into Mitchell’s onrushing troops. Fire in the front and flank produced heavy casualties for the attacking brigades.

“A poor wounded and dying boy, not more than sixteen years of age, asked permission to crawl over our works, and when he crawled to the top, and just as Blair Webster and I reached up to help the poor fellow, he, the Yankee, was killed by his own men,” wrote Watkins. “In fact, I have ever thought that is why the slaughter was so great in our front, that nearly, if not as many, Yankees were killed by their own men as by us. The brave ones, who tried to storm and carry our works, were simply between two fires.”

Rushing to the top of the Confederate parapet, Colonel McCook stood with his foot on the head log and used his sword to repulse the bayonets of the defenders beneath him. “Surrender, you damn traitors,” he shouted just before he was mortally wounded. As McCook was carried to the rear, command devolved to Colonel Oscar Harmon of the 125th Illinois. Harmon also was killed. When Colonel Caleb Dilworth of the 85th Illinois took command of the brigade, he allowed the troops to pull back a short distance to the protection of the so-called military crest, where Cheatham’s engineers should have established their main works rather than the actual crest.

A Taunting Retreat

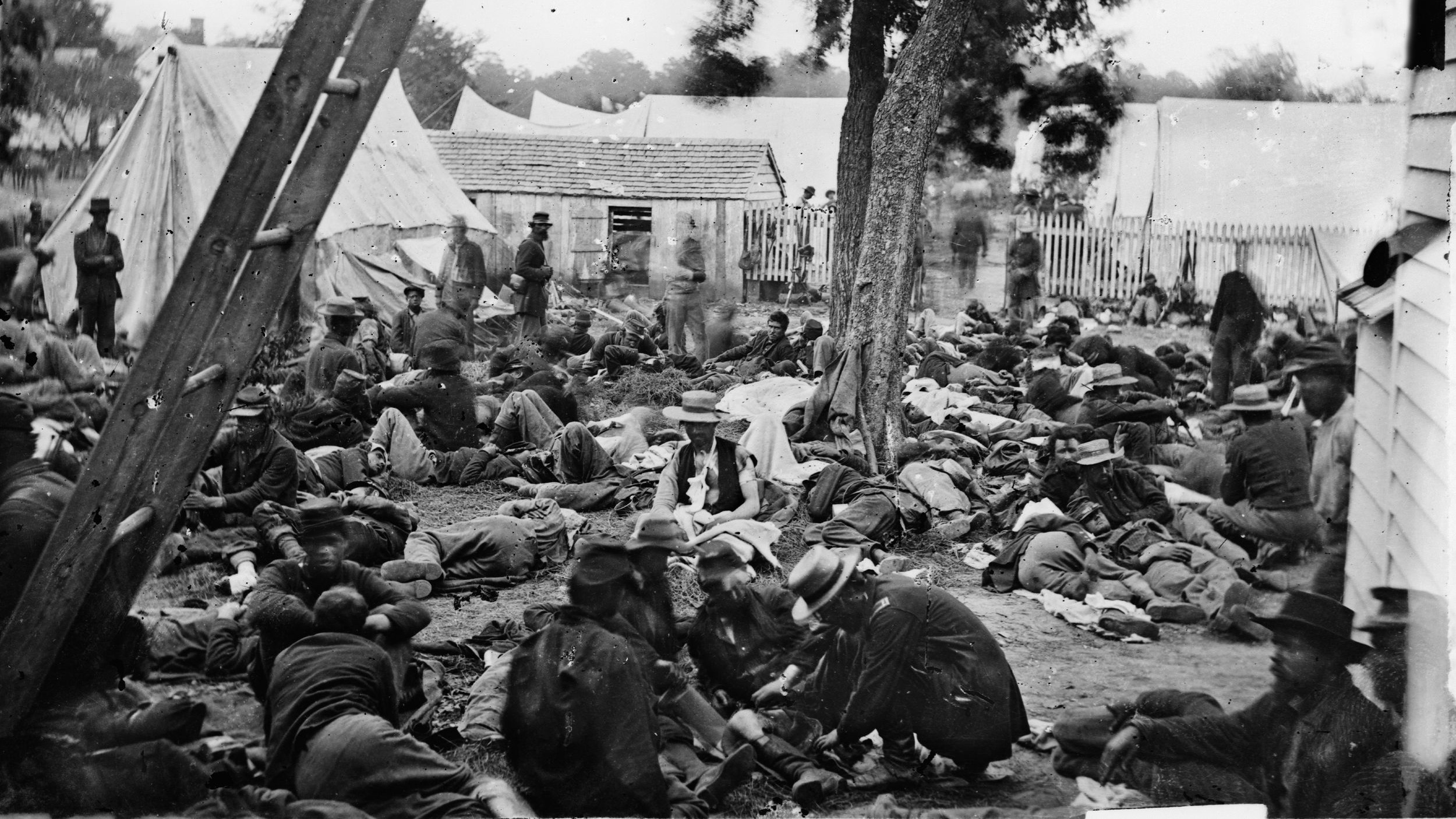

Davis sent a dispatch to Thomas at 11 am informing him that there was no hope of carrying the enemy’s line. Newton did the same. Their two brigades had suffered a combined total of nearly 1,500 casualties. Thomas advised that those who could fall back to the main line should do so, but those who could not retreat without suffering additional casualties should wait for nightfall.

The drop in the intensity of the fighting came none too soon for Watkins and his comrades. “When the Yankees fell back and the firing ceased, I never saw so many broken down and exhausted men in my life,” he wrote after the war. “I was as sick as a horse, and as wet with blood and sweat as I could be, and many of our men were vomiting with excessive fatigue, over exhaustion, and sunstroke; our tongues were parched and cracked for water, and our faces blackened with powder and smoke, and our dead and wounded were piled indiscriminately in the trenches. There was not a single man in the company who was not wounded, or had holes shot through his hat and clothing.” Many of Cleburne’s and Cheatham’s men taunted the retreating Yankees, screaming “Chickamauga, Chickamauga,” because many of those attackers had yelled “Missionary Ridge” during the advance.

While eight Union brigades numbering approximately 13,500 men were conducting major attacks farther north against the Confederate center, Schofield’s troops on the Union right quietly maneuvered around Johnston’s left flank on the morning of June 17. They achieved a small but significant gain for the Federals with minimal loss.

Cox’s Success

On Johnston’s extreme left, Brig. Gen. William Jackson of the Confederate Cavalry Corps had deployed three of his brigades astride the Sandtown Road south of the Olley’s Creek crossing. Cox had devised a plan to get additional Union infantry brigades across Olley’s Creek and push south.

The men of Byrd’s brigade had crossed the previous day a mile north of the Sandtown Road Bridge and constructed a crude bridge at their crossing point. Early on the morning of June 27, Colonel Daniel Cameron’s brigade crossed the bridge and marched south to support a crossing by Colonel James Reilly’s brigade. The movement sparked little more than a skirmish as the outnumbered Confederate troopers discovered that three full Union brigades were coordinating an advance. Cox had sent his brigades off at 4 am. He had pushed his troops relentlessly and had instructed his subordinates that he wanted them to achieve their objectives by 8 am Cox’s movement was meant to divert Johnston’s attention from the main attack to his left flank; however, Cox’s feint failed in that regard.

Cameron’s troopers pushed south to threaten Ross’s troopers while Reilly successfully crossed Olley’s Creek at 5 am. All three Rebel cavalry brigades ultimately fell back, after which Cox advanced Cameron and Reilly along the Sandtown Road to a high ridge a mile south of Olley’s Creek. By 8:30 am, Cox’s Yankees had established a four-mile line of battle with minimal casualties. Haskell deployed his skirmishers several times losing about 100 men in the process. About the same time as the Union attacks to the north ground to a halt, Cox’s brigades were entrenching on the ridge, which was the last obstacle between Olley’s Creek and Nickajack Creek.

Upon hearing this good news, Sherman told Schofield to instruct Cox to remain on the defensive, but if attacked to hold the valuable ground he had gained. Skirmishing continued throughout the rest of the day with the Rebel cavalry fighting dismounted behind hastily constructed earthworks.

Brigadier General Lawrence Ross, who commanded one of the three Rebel cavalry brigades, probed the Yankees with skirmishers to pinpoint Cox’s position and test its strength. The gains achieved by Cox and his men on June 27 became the fulcrum for Sherman’s next turning movement. Realizing he had been outflanked, Johnston abandoned his position at Kennesaw Mountain and on July 2 fell back to a prepared position at Smyrna. He then withdrew to another prepared position on the north side of the Chattahoochee River that covered the bridges and ferries leading to Atlanta.

Despite the double repulse, Sherman was not done for the day. He wanted Thomas to renew his attack. “My officers report the enemy’s works exceedingly strong, in fact so strong that they cannot be carried by assault, except by immense sacrifice, even if they can be carried at all,” Thomas responded. “We have already lost heavily today without gaining any material advantage. One or two more such assaults would use up this army.”

A Tactical Victory With No Strategic Gain

At a cost of about 700 Confederate casualties to 3,000 Union casualties, Johnston had won a tactical victory, but he had not altered the strategic situation in any way. For his part, Sherman failed to achieve his primary tactical objective, which was to punch through the Confederate center. Nevertheless, Schofield’s success against the Confederate left afforded Sherman an advantage that he exploited five days later.

Johnston’s method of fighting was not palatable to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and he removed Johnston from command on July 17, 1864. Heavy attrition in the Confederate Army of Tennessee made it practically impossible for any commander, no matter how seasoned or how much of a fighter he was, to defeat the Union juggernaut fighting its way toward Atlanta. More misery awaited the Army of Tennessee both in the trenches around Atlanta and on the forlorn march it would make into Tennessee as a last gasp under General John Bell Hood in the autumn of 1864.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments