By Kevin M. Hymel

Sergeant Carl Erickson sat in shock inside his Sherman tank as he watched emaciated people dressed in tattered, striped suits smile and feebly wave to him and his fellow tankers. “These guys were nothing but skin and bones,” recalled Erickson, who served as a tank driver. “They were so skinny their eyes bulged out of their heads.” He thought he had entered a hospital grounds filled with diseased patients. The air stank with the smell of rotting bodies and burned flesh, worse than anything he had smelled during the war. “It was horrible.”

It was April 22, 1945, and Erickson, along with his fellow tankers of Company A, 43rd Tank Battalion, 12th Armored Division—the Hellcat Division—had just crashed the gate of the Landsberg sub camp, part of the Dachau concentration camp system. Erickson’s company commander’s voice came over the radio: “Everybody, stay in your tanks!” Everyone in Erickson’s tank obeyed.

Not long after, the captain came over the radio again: “Who the hell gave them the booze?” One tanker, sympathetic to the prisoners, had given them some of his alcohol, but their bodies could not handle it. After two hours in the nightmarish compound, the tankers pulled out. Only one thing gave Erickson any kind of solace. “I heard the infantry behind us went into the town and got the townspeople to dig graves,” he recalled.

“If You Can Fix ‘em You Can Drive ‘em,”

Erickson had seen the worst of the war in Europe. He was a long way from his home in Des Moines, Iowa, where almost four years earlier he was working as a bellhop at the Savoy Hotel when he heard the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. As the only boy in a family with five sisters, his father called him “a rose among thorns.” His mother had died when he was 11. He had a girlfriend, Ruth Essick, whom he had been dating for a while. Knowing that his draft number would soon be coming up, Erickson volunteered for the Army and went to Fort Knox, Kentucky, for training and tank school. Upon completion, he remained there as a mechanic repairing M4 Sherman tanks. Ruth even came south to visit. “I thought I had it made,” he said.

When he learned that the Western Allies had invaded France on June 6, 1944, D-Day, he worried about being called to the war. He did not have long to wait. Ten days later in New York City, he and 5,000 other troops boarded the SS Louis Pasteur, a turbine steam ship that had been converted into a troop ship. Its zig-zagging journey across the Atlantic was rough, with many soldiers succumbing to sea sickness. Yet it never bothered Erickson, who had a job as a top deck gunner. The ship arrived off the coast of western England but remained outside Liverpool for two days, waiting for the tide to rise.

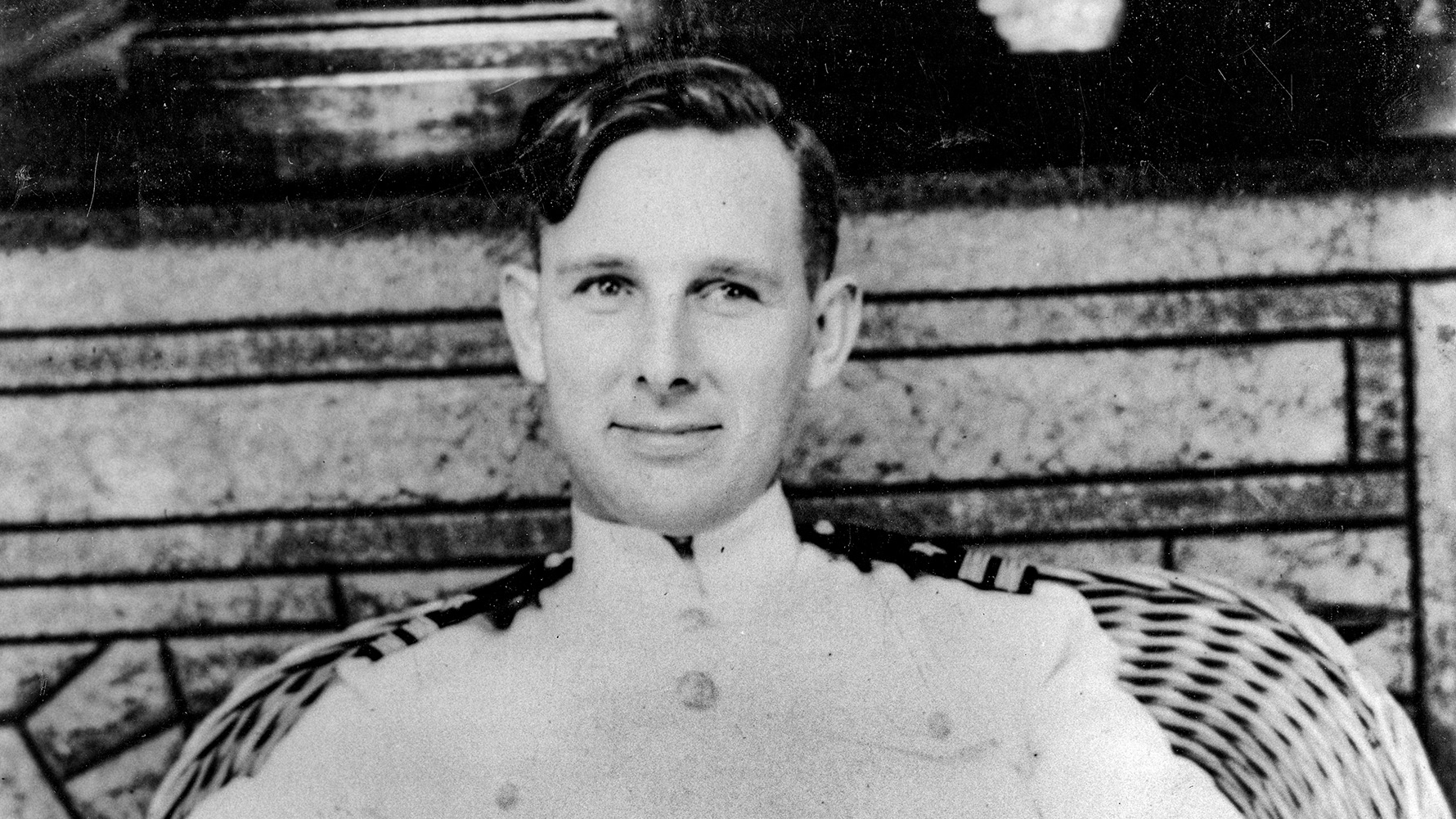

Once the ship docked, Erickson and his fellow replacements traveled across England in railcars, sailed across the English Channel, and landed at La Havre, France. At a replacement depot, he and eight other replacements stood around a table as Captain Ivan Woods from Maj. Gen. Roderick Allen’s 12th Armored Division asked everyone their military occupational specialties. Erickson said he was trained as a tank mechanic.

“If you can fix ‘em you can drive ‘em,” said Woods. Erickson was now a driver for A Company, 43rd Tank Battalion, Combat Command A (CCA). The 12th Armored fought under Lt. Gen. Alexander “Sandy” Patch’s U.S. Seventh Army, which had landed in southern France on August 15, 1944, and fought its way to the German border.

Anticipation in the 43rd Tank Battalion

The 43rd Tank Battalion was in desperate need of tankers. At the small border town of Herrlisheim in the first weeks of January 1945, German tanks of the 10th SS Panzer Division nearly destroyed the battalion and captured its commander, Lt. Col. Nicholas Novosel (originally listed as killed in action). After the battle, the Germans reported that they had captured some 300 American soldiers and destroyed 50 tanks, including some of CCB’s 23rd Tank Battalion.

“No one ever said ‘12th Armored Division,’” explained Erickson. “They said 43rd Tank Battalion.” Captain Woods, who had previously been a forward observer, introduced Erickson to his new tank crew. Today, Erickson can only remember some of their last names: Wiggins, the tank commander; Williams, the gunner; Rominelli, the loader; and the bow gunner, whose name Erickson has forgotten.

The M4A3 Sherman tank, nicknamed Anticipation, would be Erickson’s home for the next month, “as well as my bedroom and bathroom,” he recalled. The men had decorated the inside of the tank with pinups, which stood out against the white interior. Outside, spare tracks hung on the sloped frontal armor and sandbags covered certain parts, as a defense against German Panzerfausts, shoulder-fired antitank weapons.

Erickson’s driver’s seat was on the left side of the tank. There were only two foot pedals, one for gas and a clutch for shifting gears. He steered with two levers and shifted speeds with a gear stick next to his right leg. The top gear put the tank in reverse while the other four were for different forward speeds. To brake, he would pull back on both levers as hard as he could. The hatch above his head contained a periscope, which he found difficult to see through. He preferred to just stick his head out of the port. The dashboard included a speedometer and tachometer and oil pressure, temperature, and fuel gauges. Most important to Erickson was the storage space above and to the left of the instrument panel where he kept a bottle of booze. “I kept whatever I could find,” he recalled.

“I Was Blessed With a Good Gunner”

After the Battle of Herrlisheim, the 12th Armored’s next mission was to help capture the French city of Colmar inside a German-held 850-square-mile salient in the Allied line that had to be eliminated. While the French I Corps pressed from the south on January 20, the U.S. 28th Infantry and the French 5th Armored Divisions cleared the northern side of the bulge. On February 2, the 12th Armored joined the fight in the north and passed through Colmar, encountering little resistance. Once the Americans were through the city, however, the Germans put up a fight.

It was during this fighting that Erickson got to know his crew and learned just how experienced they were at tank warfare. Before their first battle, Wiggins, the commander, told Erickson to never shut off the engine in combat. “I don’t want you jerking around,” Wiggins told him. “We need to give the gunner time to lock on a target.”

Williams, the gunner, had taught gunnery before being assigned to the tank. Once, while the tank was driving along the side of a road, he spotted three German antitank guns in a field preparing to fire. He swung the turret around and fired, knocking them out before they could get off a single round. The surviving Germans ran for the rear. “I was blessed with a good gunner,” said Erickson. “He really saved our neck.”

Rominelli, the loader, was also great at his job. Erickson recalled that he could load a shell just as soon as the spent casing popped out of the cannon’s breech. One time he was doing his job so quickly that the projectile of one of the shells came off, pouring gunpowder all over the tank’s interior. Captain Woods ordered the tank off the line. It would take two days to completely clean it.

The bow gunner, too, did his job without hesitation. When the tank ran into a unit of Germans in foxholes as the sun was setting, he opened fire. “We had to dig them out with our machine guns,” said Erickson. Many Germans were killed, but a few surrendered to the armored infantry. “It kinda got to you,” he recalled about seeing dead Germans. “That was the personal side of war.”

During the fighting Erickson got to know the men of the Red Ball Express, African American soldiers driving trucks day and night to supply the frontline soldiers with food, fuel, and ammunition during the race across northern France. By the time of Colmar, any supply soldiers were considered Red Ballers. They arrived nightly at the front to refuel and rearm the tanks. Erickson would stand atop the rear right side of the tank as black soldiers handed up five-gallon gas cans that he poured into the gas tank. It took 37 cans to fill the Sherman’s 185-gallon gas tank. While Erickson poured gas, other soldiers filled the vehicle with ammunition. One night, the Red Ball soldiers grew anxious as tracers and explosions lit up the night sky. “They were tickled to death to get out of there,” said Erickson.

Erickson remembered the fighting south of Colmar simply for a lot of shooting. “We burned up a lot of ammunition,” he explained. At one point his tank was recruited as a stretcher bearer. The crew put a Red Cross flag on the tank before Erickson drove it onto an open field where the wounded were hoisted onboard for the ride back to a medical station.

The Siegfried Line

Once done with Colmar, the division turned east for the German border. Erickson’s tank reached the Maginot Line, the French line of concrete fortifications built in the 1930s along the German, Belgian, and Swiss borders. Erickson and a fellow tanker dismounted and went exploring, only to get lost inside one of the bunkers. They fumbled around in the poorly lit rooms, finding nothing but German ammunition.

“It was enough to spook me,” he recalled. Next, they came across the Siegfried Line, Germany’s line of defense. Erickson’s tank rolled through a path between concrete pylons called Dragon’s Teeth, which had been plowed out of the way.

Erickson wrote to Ruth whenever he could. To keep up his moral strength, he kept a small, steel-plated Bible in his pocket and would refer to it whenever he had time. In times of stress he repeated a particular verse, 2nd Timothy 1:12, which gave him solace: “For the which cause I also suffer these things: nevertheless I am not ashamed: for I know whom I have believed, and am persuaded that he is able to keep that which I have committed unto him against that day.”

For food, the men enjoyed the 10-in-1 rations “when they showed up,” said Erickson, but mostly they ate C-rations. There were four kinds of C-rations, but Erickson felt he only got beans and wieners. “I got sick of them things.” When the men were not eating, they smoked the cigarettes that came with their rations. “The Army learned [sic] me how to smoke,” he mused.

To keep warm during the late winter and early spring, the men would close all the hatches and keep the engine running. Once the oil in its 55-gallon tank warmed up it became comfortable. Infantrymen would lean up against the tank for warmth, and when they could the crew invited a few inside to get warm.

Almost every morning Erickson could look up and see big white streaks in the sky from bomber formations. “We didn’t see them drop bombs, but we could sure see the results,” he recalled. The air fleets smashed German cities. In one industrial area, he saw craters in the road big enough to fit a house. “We couldn’t even drive through it.”

One day while Erickson drove across an open field, a blast rocked the tank. “I didn’t know what happened,” he recalled. They had rolled over a German teller mine. The blast had bent the undercarriage, blown off a track, and torn off a bogey wheel. Erickson’s ears bled from the concussion. No one else was hurt, but he could not hear properly for days. “It was the most scared I was during the war,” he said. “You get so scared that you’re not scared, and that’s when you’re a good soldier.”

Erickson and his crew received a Sherman M4A3-E8, known as an “Easy 8,” as a replacement vehicle. The improved version of the Sherman had wider tracks, thicker armor, and a 76mm high-velocity cannon. It would not be long before that tank was damaged, too. Driving around a curve in a town, Erickson lost control. The tank slipped sideways, catching a streetcar track and damaging the tank’s tracks. “I took out about a block of track before we stopped,” he remembered.

Racing to the Rhine in Patton’s Third Army

After the battle for Colmar, the 12th Armored went into corps reserve in mid-February and remained off the line until March. During its down time, the division received several companies of African American soldiers to replenish its depleted armored infantry.

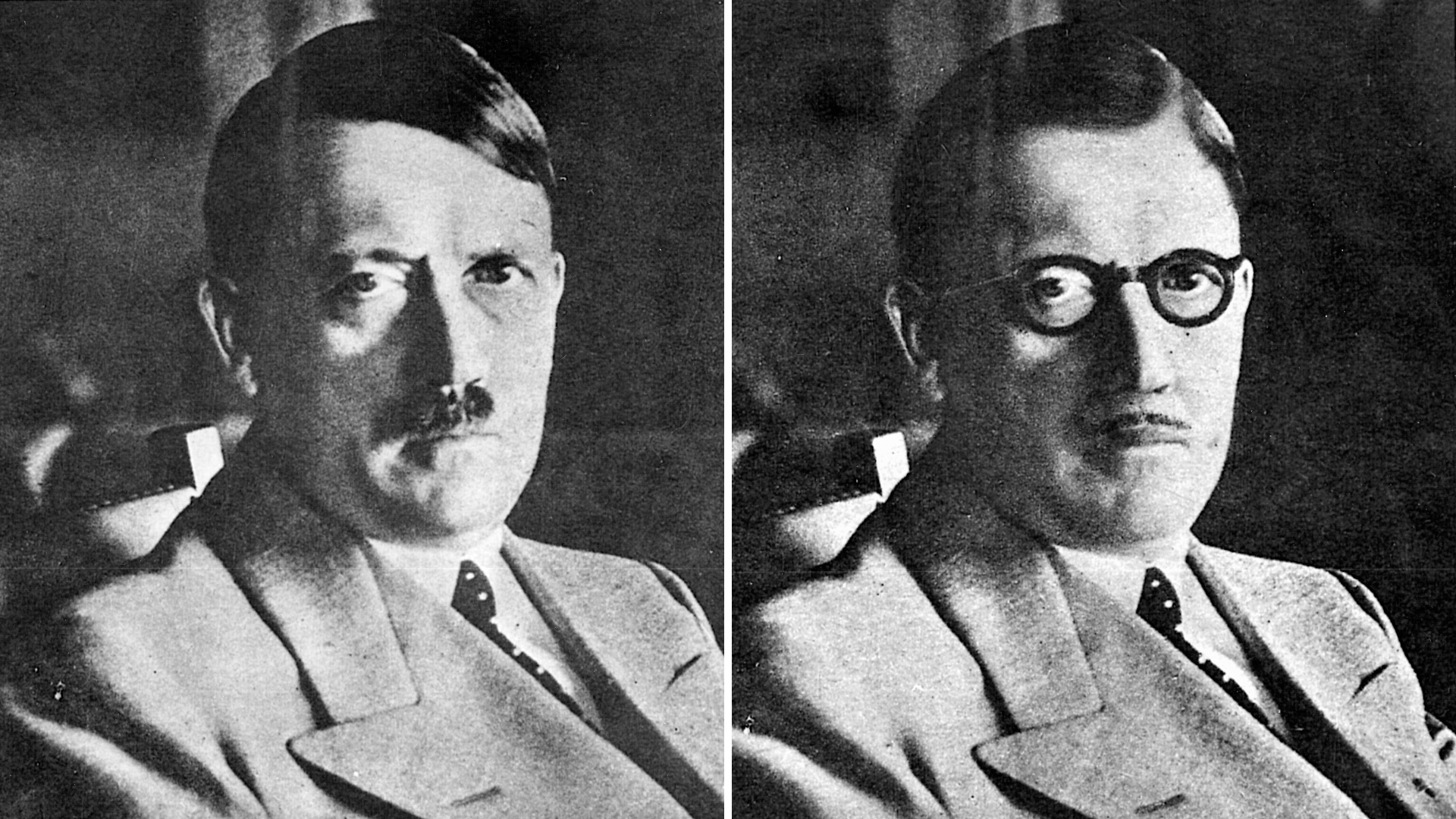

On March 17, the 12th Armored Division transferred to Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr.’s Third Army to help him race for the Rhine River, the last natural barrier into Germany. Patton welcomed the 12th Armored with a fiery speech in a large field near Sierck-les-Baines, France. Erickson remembered that Patton preached to the men: “I’ll reach the Rhine first if I have to take a 6-by-6 Mack Truck to haul back the dog tags!” One of Patton’s first orders was for everyone to remove their division patches to keep the Germans believing the 12th was still under Seventh Army.

The 12th started the drive for the Rhine the next day, barreling through light opposition. Erickson remembered passing through the German city of Trier, which had been captured by the 10th Armored Division two weeks earlier, but he had no recollections of seeing either the city’s black gate (the Porta Nigra) or the Roman amphitheater. Elements of the 12th reached the Rhine on March 20 and four days later linked up with the 14th Armored Division coming up from the south.

Erickson crossed the river at night near the city of Worms over a treadway bridge. Guided by an infantryman, he drove slowly across the bridge. The tank rose as it approached each pontoon and dipped as it rolled off. “If I had seen that in daylight,” said Erickson, “I would have gone AWOL.” His one regret: “I didn’t get a chance to see Patton water the Rhine,” he said about the General’s famous bathroom break.

“Get Off That Highway!”

Relief from the front was never long. Once while the men were resting and relaxing they received orders to relieve another armored division. Erickson’s tank joined a convoy of tanks charging for the front. In the distance he could see a fork in the road where an MP with white gloves directed traffic next to a jeep in front of a house. But by the time Erickson’s tank reached the fork the MP was gone, the jeep had been flattened, and the house’s front steps had been crushed. The tankers did not have time to stop, much less slow down.

Once the 12th crossed the Rhine River it returned to Patch’s Seventh Army on March 24. It had fought under Patton for only a week and was now the spearhead for Seventh Army. The division was given a short break before returning to battle. Erickson and his crew enjoyed themselves in Heidelberg by liberating three large beer barrels. They placed one on the front of their tank and two on the back. As they rolled along, their engine heated up the beer barrels in the rear. The cork on one of the rear barrels blew out, and a stream of beer shot 20 feet into the air. Erickson had to take an axe to the barrel to open it. “We lost half of that beer,” he lamented.

In early April, Erickson’s company approached the German town of Würzburg, and a Panzerfaust round exploded against the tank in front of him. The damaged tank stopped. Erickson watched as a German came out of a building and walked around the tank. Suddenly, a tanker named Allen jumped from the top of the tank onto the German. “He gave the German the Brooklyn version of the goose,” explained Erickson, meaning he stuck two fingers into his eyes. Then Allen grabbed the German’s Mauser pistol and shot him. “I can still see that,” recalled Erickson.

The tanks used the Autobahn to penetrate deeper into Germany. One day while Erickson was cruising down the highway, he spotted a German tank, possibly a Tiger tank, open fire on him from half a mile away. Captain Woods shouted over the radio, “Get off that highway!”

Erickson turned the tank around and raced away. “I was going fast enough that my tracks made a round circle,” he joked. A P-47 Thunderbolt fighter flew in and blasted the tank, then came back waving its wings. It would not be the first or last time fighter planes helped out Erickson’s company. “When we got into a battle and needed them, they always seemed to be there.”

Combat took a toll on the tankers. “We lost a couple of them from going berserk,” said Erickson. A new second lieutenant who took over one of the platoons could not make it through his first skirmish. When the bullets started to fly, according to Erickson, “he lied [sic] down at the bottom of his tank and cried like a baby.” The men pulled him out of the tank and dragged him behind a building. “That was a big thing to talk about.”

“They Were All Little Kids”

The 12th continued eastward. On April 22, the tankers fought their way into the town of Dillingen on the Danube River, where they found German soldiers preparing a bridge for demolition. While Erickson and his fellow tankers fired across the river, the armored infantry charged the bridge.

“We caught them by surprise,” said Erickson. Once they chased the Germans out of the area, the Americans discovered six 500-pound aircraft bombs underneath the bridge. Engineers were called in to deactivate the bombs. Erickson’s crew spent the night on the west side of the bridge and crossed the next day.

Four days later, Erickson followed another tank through the gate of a large complex near Landsberg. That was when he saw the evidence of Adolf Hitler’s real Germany, the Landsberg Concentration Camp. Erickson left the camp shocked at the sight of so many human beings so close to death, but he was pleased to hear the infantry had put the local populace to work digging graves.

Erickson appreciated his armored infantry for the support they gave the tanks. One day while cleaning out a town, an African American infantryman asked Erickson if he could trade him his M1 Garand rifle for the tank’s Thompson submachine gun for the day. Erickson made the swap, and before the day was out the man returned the Thompson with three empty magazines. They continued the routine for a while until the infantryman failed to show up one day. “He was too honest a fellow,” Erickson lamented. “We took care of each other all the way around.”

The Germans, with few tanks and almost no gas, relied more and more on Panzerfausts, which were not always effective. One tank took a hit right on the front corner where two armor plates were welded together. “That round never came in,” explained Erickson. One night the Germans had dug into the side of a hill, where they fired Panzerfausts in an effort to slow the speeding tanks. It did not work.

In one of Erickson’s final battles, his company ran into a unit of fanatical Hitler Youth. “We had to fight our way through them,” he said. One of the American tanks fired on them with a flamethrower. “They were all little kids,” Erickson explained, “but they all had guns.”

Collapse of the German Army

As April turned to May, the German Army imploded. Erickson saw thousands of surrendered Germans walking west into prisoner of war camps. He offered them cigarettes and food. “There was no fight left in them,” he explained. The division liberated more than 2,800 Allied prisoners, including 1,400 Americans. Erickson recalled seeing large numbers of liberated Americans walking on the roads in the beautiful countryside. “I really didn’t think we were that close to the end of the war,” he recalled.

On May 4, the 12th Armored Division went into reserve. It would be its last day of war. Four days later the tankers learned the Germans had surrendered. “Everyone went crazy!” said Erickson, but no one had anything with which to celebrate. Erickson eventually got his hands on a five-gallon pail full of potato vodka schnapps. The men rapidly killed it. “Not a soul showed up next day at roll call,” he remembered. “It was a happy time.”

When Erickson turned in his tank, it was missing its Thompson submachine gun but contained the African American infantryman’s rifle. No one cared. “We were celebrating,” said Erickson.

Erickson was put in charge of a house billeting soldiers. The woman owner served as the maid and cleaning lady. One day two of his buddies butchered two of her chickens. She furiously complained to Erickson, but he could not understand her. To make it up to her, he retrieved a can of coffee grounds from the mess hall and gave it to her. “She was tickled pink!” he laughed.

While the war in Europe had ended, Japan fought on. The 12th Armored Division was selected to be part of the invasion of the Japanese home islands. Erickson and his crew departed France in a Liberty ship headed for the United States. Halfway across the Atlantic, they learned the United States had dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, and then Nagasaki. Finally, on August 10, the men learned that Japan had surrendered. The war was over. Erickson spent the trip playing cards and dice. “I had $1,400 in my pocket when I left,” he recalled. “When we pulled into New York I had none.” It was the last time he ever gambled.

As Erickson’s ship approached New York City, he stood on deck for three hours just watching the Statue of Liberty fill the horizon. Once docked, the men disembarked and reported to Camp Shanks, where they enjoyed T-bone steaks. “It was the best steak I ever ate,” he recalled.

Soon, Erickson boarded a train to Philadelphia and then transferred to one bound for St. Louis and finally to Spencer, Iowa. As the train neared its final destination, Erickson began to cry, but he decided he did not want to be a baby and stopped. Ruth, his father, and sisters were waiting for him as he stepped off the passenger car. Erickson was home.

A Life After War

Within a month of returning, Erickson married Ruth. They had five boys and one girl. One of the boys, David, served with the U.S. Air Force in Vietnam where he loaded Agent Orange onto planes. He later died of cancer, most likely related to his service. Erickson also lost his daughter, and Ruth died in 1977. Erickson married his sister-in-law, Ardie, and they have been together, as of 2016, for 40 years. She brought two sons and three daughters to the marriage. Together they have 11 children, 29 grandchildren, 44 great grandchildren, and three great, great grandchildren.

Soon after returning home from the war, Erickson used the GI Bill to learn machine work and took a job in a forge. In 1960, he bought his own shop in Albert City, Iowa. He eventually sold it to his sons and bought a John Deere dealership in Montana, which he owned for five years before going back to Iowa and working in a welding shop until he retired.

Erickson never spoke about the war until one of his adult sons asked him to address a classroom about his experiences. It was hard, but Erickson faced his past and explained the horrors of World War II to the students. He has been comfortable speaking about the war ever since, although he cannot always remember all the details.

While Erickson did not always talk about the war, he did think about it from time to time. One memory that stuck with him was the African American soldier who used to borrow his Thompson submachine gun. Erickson reflected some 70 years later, “I often wondered what happened to him.”

In the late 1990s, Erickson visited the 12th Armored Division Memorial Museum in Abilene, Texas. He spent three hours touring the artifacts and reading the information panels. Then he entered the museum’s Holocaust Room. “It just threw me,” he recalled. “I could smell it, but it was just something in my head.” The war, so far behind him, could still feel immediate. The smell of dead bodies still lingered in his nostrils.

Frequent contributor Kevin M. Hymel is the historian for the U.S. Air Force Chaplain Corps and author of Patton’s Photographs: War as He Saw It. He is also a tour guide for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours and leads a tour of General George S. Patton’s battlefields.

Love reading and listening to these stories. My grandfather name was also Carl Erickson. I think there’s a lot of Carl Erickson’s. My dad’s brother served in WWII. Never talked about much. Hope one day to go visit Normandy one day and travel the same roads our troops traveled. I myself served in the US NAVY in Vietnam. Thank for the great story.