By Jack Hildebrandt wih M.M. Harris

It was November 1, 1944. I, Feldwebel (Technical Sergeant) Gustav Jack Lothar Carl Herbert Julius Hans Jergen Hildebrandt von Lengerke (aka “Jack” Hildebrandt), had just completed a successful strafing run against British General Bernard “Monty” Montgomery’s advancing army along the southern end of the Dutch-Belgian border.

Enemy ground fire had forced me to break out of the Schwarm (formation). Alone and feeling threatened, I piloted my Focke-Wulf FW-190 Würger (“Butcherbird”) down low to 500 feet and applied evasive maneuvers such as hedge-hopping to avoid enemy flak. The antiaircraft guns were well concealed between the Waal River and the Dutch canal.

Approximately 30 miles away and barely visible on the horizon was the German line in the Netherlands. Safety was only minutes away.

WHAM! The fighter lurched violently up and to the right. The cockpit glass imploded and freezing air and smoke swirled around me. I was stunned by the explosion. Thank God for my goggles and oxygen mask. A few seconds passed before the oozing of blood spreading across my flight suit and searing pain in my left arm and leg snapped me back to reality.

My left hand swelled up in seconds like a donut, and my left leg did not work the rudder too well. I managed to raise my arm, and I almost passed out by what I saw. I could see daylight through my elbow!

My bum began to throb, so I must have stopped some hardware as well. However, my physical condition was the least of my worries. The 190’s engine was on fire, and the flames started licking toward the left wing and the cockpit. Already I was too low to bail out, and with the engine on fire there was no chance or time to climb. My only hope was to belly land—anywhere—as quickly as possible.

Over the nose and through wisps of smoke, I spotted the Huisden Bridge over the Waal River. Beyond it was the German line and a sprawling pasture. Aiming for the pasture, I fought desperately to keep the crippled plane in the air. Adrenalin kicked in. I was half paralyzed from shock and pain. Fighting nausea and a strange sense of euphoria, I forced myself to stay focused. “Put the damn thing down as fast as you can, before the fire gets to you!”

The fire was spreading—I was about to be burned alive! As the bridge over the river loomed ahead over the nose, I knew I had reached the German lines. The pasture was dead ahead. I released the controls, reached under the canopy, and fired the explosive cartridge that blew off the canopy. The fighter hit the ground with a ferocious impact, its force slamming my head into something sharp. The plane cartwheeled and skidded, then came to an abrupt stop.

In and Out of Consciousness

Stunned and disoriented, I do not remember how I got out of the wreckage and into one of the numerous foxholes the Germans had dug along the roads in occupied Holland—a good 150 feet away. They were necessary because of the enemy Thunderbolts, Mustangs. and Lightnings that wreaked havoc with anything that moved on the roads.

What I do remember is the plane blew up in a large fireball. Then I must have passed out. The time was 3:30 pm, and this was the somewhat ignominious end of my flying career with the Luftwaffe. I had flown 86 missions, having been shot out of the air by ground fire rather than a glamorous finale brought about by an enemy fighter.

I had been shot out of the air once before—in March 1943 behind Soviet lines, but at that time I didn’t stop any lead with my small body. This truly was journey’s end.

As I regained consciousness, I began to shake uncontrollably and my teeth chattered—from shock, I suppose. I don’t know how long I remained in that foxhole, drifting in and out of consciousness, before a German Army roving patrol arrived on the scene. They had seen the remains of the fighter and looked for the pilot in the roadside holes. They found me alive, much to their surprise (so I was told). They carried me to their vehicle and took me to a frontline aid station, where I passed out again.

The next time I regained consciousness, I was on a stretcher wearing a green sleeveless sweater I had never seen before—and nothing else. Those rotten German medics had stolen everything I had on my body—my automatic, my sealskin wallet with my personal pictures in it, my Luger (Pistole 08), flying boots—everything. I had been warned about those thieving German medics, but you can’t do much for yourself when you’re unconscious.

An American in the Hospital

I was lying on the floor in a large, cold room with the windows apparently blown out. This was northern Europe in November, and the temperature was below freezing. The chill caused my oozing wounds to feel as if they were crawling—a ghastly feeling. I began to scream. A young German doctor rushed over and quickly gave me a shot of morphine. Then he ordered me prepared for transfer to the local hospital in Utrecht for surgery.

The medics carried me on a stretcher and placed me in another room already filled to capacity with other severely wounded and dying soldiers. They were lying—just as I was—on straw mats placed directly on the freezing concrete floor. The nonstop whirlpool of crying and moaning was, in itself, indescribable agony.

The morphine removed the edge of pain and fear. I felt myself begin to slip into a state of blissful uncaring. Maybe I was afraid I would never wake up again. In spite of the pain, I gritted my teeth and forced myself partially upright. There was a body next to me. I reached out and touched him. Nothing. He was dead. I turned away. On the other side of me was another soldier, half moaning and half crying. I knew the feeling.

But something was different about him. Through bleary eyes, I noticed that his uniform was a strange khaki color, not the green worn by Germans. Sensing an intruder, he looked straight at me. Then he spoke—not in German, but in English. American English.

Taken aback, I mumbled something in what few words I could come up with in English. We formed an immediate bond. We didn’t seem like enemies; we were seriously wounded soldiers. Our newfound comaraderie distracted us from our own unbearable pain. Although our conversation was halting and stilted, it was friendly and meaningful. While we talked we shared a government-issue German cigarette.

I learned he was an American prisoner of war, a paratrooper from the 101st Airborne Division, the Screaming Eagles. This man held a great fascination for me, for I had never met an American before. Bob (I think that was his name) was from Wisconsin, and he spoke nonstop of his love for his country, America. What a wonderful place, so seemingly different from the Old World’s traditional nationalistic hatreds, rivalries, dense population centers, and narrow mindedness.

We got along famously for about two hours, and then, suddenly, four medics appeared and carried him out, away from me. They did not want me to talk to the American. I was instructed never to speak to any prisoner of war under any circumstances; it was considered treasonous conduct. If Bob is still alive and happens to read this, I want him to know he was one of the factors that convinced me the United States was where I wanted to be.3

Hospital Under Fire

After my new friend was taken from me, I once again sank back into pain and despair.

About two hours later they shoved me into an unheated ambulance. The ride to Utrecht was a real “ball breaker”—that ambulance sported a suspension like a Mack truck. The fact that we were constantly strafed by Spitfires on the way added little to the enjoyment of the ride. Two of us four guys in the ambulance were dead by the time we got to the hospital.

Upon arrival, there was total chaos because this was close to the advancing Allied front. There were too many wounded German soldiers and not enough medical staff. The German nurses and most of the surgeons had all been evacuated. Only a few very brave and dedicated doctors stayed behind.

A rather stunning blonde Dutch nurse seemed to take a shine to me and persuaded a German surgeon to operate on me. My proverbial good luck appeared to hold, and soon my gurney entered the operating room. Survivors of the world, unite! I received ether and went under. Good night, world….

I woke up screaming in pain. My left arm, cut completely open from the inside of my elbow down to my hand, stuck straight out from my side, revealing bone, tendons, and muscles through pieces of bloody flesh. I was flat on my back strapped to an operating table. The surgeon was lying dead across my body, still clutching the bloody scalpel in his hand. The operating room nurse lay dead in a grotesque heap on the floor.

Above me, the ceiling of the operating room had departed the building, exposing a beautiful wintertime blue sky dotted with fluffy white clouds. In the distance, birds chirped away as if nothing terrible had occurred. What was once the makeshift operating room of a hospital was now the ruins of a bombing raid; rubble, bodies, and debris were strewn everywhere.

I shattered this otherwise beautiful day with my blood-curdling screams: “Medic! Medic!” Oh God, the pain!

Wonder of wonders, a medic showed up. He had assumed I was dead along with everyone else—that is why nobody bothered with me. He gave me a shot of morphine and said he would try to get me out on a hospital train that was leaving for Germany within two hours, with any luck. The entire hospital—what was left of it—was being evacuated in a hurry. The doctors put a chest cast on me to support my arm that stuck out forward from the left shoulder. My left lower leg and bum were heavily bandaged.

The Fate of Wing Squadron Number 63

The so-called “hospital train” was, in reality, a string of cattle cars filled with stretchers—36 men per cattle car, I believe. They were stacked both vertically and horizontally as close together as possible with barely any clearance between them. I was on the bottom and—wouldn’t you know—the malodorous community chamber pot was beside me.

I kept rolling out of my stretcher because my chest cast, nicknamed “Stuka” because it stuck straight out like the wing of a Stuka, elevated my arm to shoulder height and stuck straight out, making it impossible to lie straight in my stretcher. This did little to alleviate my intense pain.

I tried to hang on tight, but each jiggle and each turn brought on unendurable spasms of pain. Sometimes I had no choice but to let go, ending in a face-down landing in the chamber pot.

During this arduous ride, a medic let it be known to me that my squadron, SG 63, or Schlachtgeschwader 63 (Wing Squadron Number 63), comprised of approximately 30 aircraft, had been transferred to the Dutch Channel Island of Walcheren where the entire unit perished during an Allied bombing raid.

Delirious from pain and exhaustion, I couldn’t stop the flood of tears. Why them and not me? I felt sick that I was alive and they were all dead. My nanny’s witty aphorisms echoed through my mind. “You can’t kill an ill weed!” she used to say. “This boy was never properly born. He fell off a donkey galloping out of hell!”

I loved my nanny. Her aphorisms were country earth. I couldn’t help but wonder: Was she still alive? Or was she, too, dead? I was obsessed with their deaths and heavily laden with guilt as to why I escaped death’s grasp over and over again while everyone around me perished. Guardian angels came to mind….

The Nuns of Burgsteinfurt

It took us almost two weeks to cover the 200 miles from the Netherlands to Burgsteinfurt in northern Germany. The train was bombed time and again. People died like flies. Not me. The tracks were torn up by bombs and had to be fixed. As soon as they had been fixed and we moved a few miles, they were bombed again.

For injured soldiers traveling on a train with inadequate facilities to protect and care for them was hell. Other than morphine, there were no medications on board. During the ride, my arm turned green and reeked of gangrene. With no other medication to fight the infection, my condition deteriorated rapidly. I heavily depended upon the morphine. My arm became gangrenous, and I lived on morphine all the way from Utrecht to Burgsteinfurt. Frankly, I was barely alive.

Upon arrival we were all taken to a hospital that was conveniently located one mile from a V-1 buzz bomb launching site, which did little to add to my emotional tranquility. This place was run by nuns.

Let me tell you about nuns. Mine was wearing a black dress with large white headgear and some sort of white apron in front. I don’t know anything about religion, except it tells you to be merciful, kind, and helpful to your fellow man. This nun must have been standing in the goulash line when they were passing out mercy.

I had wasted away to 115 pounds from my diet of mostly morphine with a little food for the past two weeks. I was hefted on a table for a change of dressing. This purveyor of kindness ripped off my old dressing in a manner that would make a Gestapo man proud. My bare elbow bone was sticking out, cruelly exposed for everyone to see, and this angel of mercy took the old dirty bloody paper bandage—the front line had run out of gauze dressing months ago—and wiped my bare elbow bone with fierce dedication. I hauled off and sent her flying across the room, and then I passed out again.

“Amputation Will be Futile.”

I woke up in a hospital room in a bed with clean sheets, properly bandaged and sedated, and the doctor came and apologized. I could tell the Germans were losing the war and the end was near.

Have you ever heard of the fire raids on Hamburg and Dresden where tens of thousands died and melted in the streets? Well, there was another fire raid on Würzburg in March 1945, which I was about to find out.

The previous December, they had shipped me from Burgsteinfurt to Würzburg to a hospital for the gravely wounded. There were 46 military hospitals in Würzburg at the time and very little else except medieval architecture and its famous Franconian Boxbeutel wine.

The hospital business was very good in Germany in 1944. I arrived at 1:30 am on a bitter cold December day. The cattle car doors were slid open, and the wounded were removed, one by one, to ambulances waiting by the track. While this was going on, we waited with the doors wide open and an outside temperature of minus 7 degrees Fahrenheit, with a much worse wind chill factor.

I was frozen stiff when I was loaded into an ambulance about an hour and a half after we arrived. We were delivered to Marian Hill Military Hospital for the seriously wounded, where we were immediately put into warm rooms with clean sheets on the beds. They really took good care of us when they could.

The chief surgeon, Professor Narath, made the rounds with his surgical staff. He took one look at my arm, and I was on the operating table in 15 minutes. This was at 3:30 am. I have never seen such fast action again in any hospital.

While I was lying on the operating table inhaling ether and half under, there were a number of people in white surrounding me, and I could hear them talk. They thought I was already under, but I wasn’t. Being German and from the wine land of the Rhine, I have had a fondness for libations from early childhood, and maybe that is why it took me longer to succumb to anesthesia.

One surgeon said, “Advanced gangrene. The arm is black. We’ll have to amputate. We’ll have to take it off above the elbow, maybe that will do it.”

Professor Narath announced, “Amputation will be futile. This little guy will be dead by tomorrow night. The gangrene has gone too far. It will affect his vital organs before too long. Let’s just drain him and send him to his room.” There were 31 more cases outside waiting to be operated on.

Right then and there I became determined not to die, if only to spite them. Lo and behold, the next night the chief surgeon looked in on me and shook his head in disbelief. I was still alive—just barely—but alive.

A Visit From Father

The next morning by my bedside, there was my father, whom I had not seen in 14 years since my parents’ divorce, and my mother, who was crying. The hospital had sent them a telegram saying I was dying. Ha! Fat chance! You just listen to my nanny.

My father was on military leave and had only one day. He had never worn a uniform in his life and had no use for the military, being a corporate lawyer. My father never could keep his mouth shut when speaking out was needed, and I truly admired him for that, but he kept speaking out against the regime—a very unhealthy habit in Germany after 1933.

So the Gestapo had rounded him up and placed him in a penal battalion with the assigned duty to collect dead bodies from shelters while Allied air raids were in progress and bombs were falling all around. This was the Gestapo’s ingenious method to avoid overcrowding of death camps.

My father had to leave me the following day, but my mother stayed a whole week. They had given her one week’s compassionate leave from her assigned national service job in a medical manufacturing plant where bandages, stretchers, prostheses, and such were made. My mother managed to come up with all kinds of unavailable culinary treasures such as eggs and red wine and chocolate to give me strength. Where and how she got this bounty, I’ll never know. She died in Germany in 1989, two days before her 100th birthday. She never could complete anything.

By the way, my father made it through the war. He was saved from death at Nordhausen near Kassel by the advancing Americans just as the Germans were getting ready to execute him. Nordhausen was an underground site buried in a mountain where the Germans produced the V-2 ballistic missile launched against England. They expended slave labor to manufacture these missiles. My father had been sent there to contribute to the consumption of expendable Germans.

An Addiction to Morphine

Miraculously, my health began to improve despite the pain, which did not subside. All that held me in check were the four hefty doses of morphine I received daily. Soon, predictably, the effect of the drug diminished, and my relief from pain declined. In short, I was addicted.

By now, only people who had to tend to me came anywhere near my room. I certainly wasn’t anything to look at. My chest cast was gray and dirty, and my lower leg was wrapped in bandages where the surgeon had taken out a six-inch piece of metal. My arm exuded mephitic vapors. I had a six-week-old beard. I could not take a bath because of the Stuka.

Still in pain and terribly malodorous, I was getting better, but not much. The gangrene was going into remission! Can you believe it? I believe I am the only case in German medical history until 1944 of gangrene reversal.

By this time I was getting four injections of morphine a day. The dosage was getting heavier and heavier because I was addicted. My dependence had become ruinous. The pain relief period grew shorter and shorter, and the dosages needed to be increased constantly.

After a while, the doctors resorted to what I believe was called “S.E.E.,” something on the order of pentothal which was normally used for general anesthesia but which, at this stage of my addiction, was the only drug that relieved the 24 hours a day, seven days a week agony—but only somewhat. The last injection of the day would be administered at 9 pm. I would lie in my bed and promptly at 8 pm—I could set my watch by it—the pain would begin to intensify until 8:45 pm, when the torment became so savage it was almost unbearable.

Those last 15 minutes before the night nurse arrived with the morphine were sheer hell. I suspect in the beginning they gave me morphine to keep me quiet because I was a rather testy and demanding patient.

As a result of my addiction, I lost my appetite but drank about 40 bottles of seltzer water a day because of the raging fever from the gangrenous arm. I now shared a room with a man who had a near-fatal case of malaria. He was moved out of my room because I smelled so awful, because even he could not stand it—and he was unconscious half of the time, when he was not delirious.

Cold Turkey at Bayonet-Point

If you have ever had a whiff of a decomposing body, that is what I smelled like because I was sort of decomposing while I was alive. But I hung in there. Remember what my nanny used to say? “You can’t kill an ill weed!” Dear old nanny. How right she was. I bet she is up there looking down on me, saying, “I was right. That boy fell off a donkey galloping out of hell!” I hope she is in a good place, because if anyone ever deserved it, my nanny did.

Several days later, Professor Narath, the chief surgeon, looked in on me. I was not healing, he told me. I was losing weight, and I was too skinny already. The wounds continued to suppurate. It was all due to almost three months of morphine four times a day. He was taking me off the morphine—cold turkey—as of right now.

This was ominous news. I was so hooked on morphine I could hardly get through three hours without it. What was I going to do? Do you remember The Man with the Golden Arm, starring Frank Sinatra as a drug addict making a gut-wrenching effort to shake the habit? Well, my friends, I have known the hell through which he went trying to achieve freedom.

The first day and the first night, I honestly believed I was going to die from the pain. At that time, dying looked like a promising prospect because the agony was so savage it defied description. I was thrashing around in my bed, Stuka and all, writhing on the floor and practically climbing the walls, grunting and groaning like a wounded animal.

The second night around 3 am, I was half mad with pain. I got out of bed and peeked around the corner to make sure there was no one in the hallway, gritted my teeth, clenched my fists, and hopped down to the nurse’s office on my shaky good leg. I was wearing a very short shirt that came down to my hips and was tied on the sides to fit over the Stuka. My lower half was uncovered and completely exposed to the freezing temperature. There was no heat in the hallways or the john—this was January 1945 in Germany.

I hopped along to the nurse’s office. No one was there. Peachy keen! I hopped inside and there they were, lying on the medication table: dazzling little ampules. I started to saw off the tip of one vial when I felt a heavy hand on my shoulder. I looked up at the chief surgeon, Professor Narath, all 6 feet 3 inches and 245 pounds of him. I am only 5 foot 6.

He escorted me back to my room and stated, “Starting at 0700 hours today, I am going to post an armed sentry in front of your room with fixed bayonet and I am going to order him, if you attempt to wrestle him, to stick you—not very badly, but enough to discourage you! No more morphine, is that understood?” What could I say? He outranked me.

There followed 30 days that probably were the most desperate period of physical agony I have ever experienced. But to this day I am deeply grateful to Professor Narath for putting me through this agony. It showed me I could overcome any addiction if I determined to do so.

Doris’ Visit

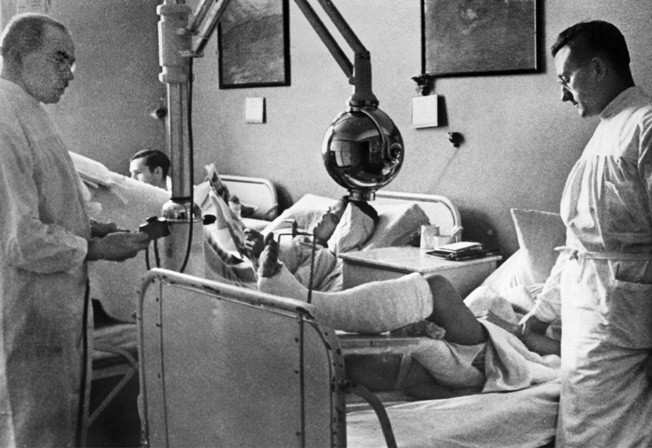

When I was finally free of the morphine—the monkey on my back—I began to heal quickly. After I completely healed, I had a sequence of neurosurgical procedures—also performed by Professor Narath—to repair the severed nerves in my left elbow. Lucky for me, the professor was one of Germany’s foremost neurosurgeons.

My left elbow had been smashed when I was shot out of the air. The nerves were severed, and my left arm was useless. I could not move the fingers of my left hand. I could not move the elbow at all. There was no medical record of what surgery had been done on me in the Netherlands; during the bombing raid on the hospital, all records had gone up in flames.

So, Professor Narath started from scratch. I had six sequential nerve sutures, and each procedure was followed by a lengthy recovery. All were an astonishing success. My arm was not amputated. Eventually, I regained full use of my left arm and hand. Just one more miracle in my life!

“Hello, Hero. I’m Doris.”

At first I thought I was hearing things. I was almost asleep when the melodious voice of an angel seeped into my dream world. My eyes squinted open. All I could see was a shadow of a feminine figure behind my bed curtain. This was some dream!

I blinked rapidly while simultaneously giving thanks to whatever higher power must be responsible for this apparition. Was I hearing things? Just then, a well-manicured hand reached in to pull back the curtain. Slowly, this wide-eyed brunette peeked around the corner. “Hello, Hero. I’m Doris. Remember me?”

Doris? The only Doris I knew was a freckle-faced girl from across the street whom I used to try and shoot in the bum with my BB gun in my hometown of Wiesbaden. Doris? And how! Doris had huge, beautiful brown eyes and bright red luscious lips, and she sure had filled out in all the right places. Before I could answer, she pulled up a chair and made herself comfortable. It was soon revealed that my mother had notified her by mail of my hospitalization after she learned that Doris and her parents had moved to a nearby town on the outskirts of Würzburg.

From that day on, Doris was my constant companion. It didn’t hurt that she established herself as the nurse’s pet, which afforded her the privilege of staying beyond visitation hours. Our chemistry was potent. Lucky for her, my Stuka was attached to the ceiling, thus discouraging any contact. Lucky for me, I was approaching a condition where I could perhaps get out of bed and ask for a pass to go into Würzburg, but not quite yet. Doris came to see me every day and, depending on who the duty nurse was, usually stayed beyond visiting hours.

“Your Stuka is Coming Off”

About two weeks after Doris’s first visit, the medic came in and announced, “Your Stuka is coming off.” Boy, was I ever glad! With shears, clippers, scissors, and muscle power, the two medics removed the cast. When it was off, my left arm looked like a purple pencil. It hurt so badly hanging down in its natural position, I wished the medics would put the Stuka back on.

Then the dispenser of military medicine told me, “Follow me!” We proceeded into the bowels of the ancient building, which resembled a torture chamber. I found out later that was exactly how other patients referred to it. It had the appearance of a dungeon with an array of sinister looking devices.

I was holding up my left arm with my right hand. The medic told me to sit down in one of these medical marvels, strapped me down, and attached my left arm to some receptacle. He turned on the machine, left the room, closed the door behind him, and left me screaming while the machine bent and extended my arm without mercy. I nearly passed out from the pain. It was only my rage that kept me conscious.

Thirty minutes later, the medic returned to stop the so-called physical therapy. You think the Germans only treat non-Germans that way? Think again.

Several of these tender, humanitarian episodes later, my arm was somewhat more flexible. And—oh joy!—I could now ask for a pass. When Doris came to see me the next time, I told her I could go out on pass, and we planned for a day together. There wasn’t very much to be had in restaurants in Germany in February of 1945, but in Würzburg there was still Boxbeutel, the famous Franconian wine, and some basic fare.

A Brief Return to Normal Life

After three months of confinement, I could hardly wait to get out of my hospital garb, get into my uniform again, and see the city. But in order to do so, first I had to be in uniform to walk three miles to the air base on top of the hill, where I would be issued a new Luftwaffe uniform. I was allowed to rummage through the hospital supply room, where I found an Army uniform that was several sizes too large. I looked like a clown, but I didn’t care.

At last I got myself a new Luftwaffe uniform, complete with all my medals and my pilot wings, and an overcoat, which was badly needed in this cold climate, but which I could only wear draped over my shoulders a la Napoleon because I was unable to get my new, smaller cast through the left sleeve.

Doris came to the hospital around 2 pm. There was a brief moment that brought tears to both our eyes when she saw her hero in uniform for the first time. During that undefinable moment, I was consumed by the realization that not only was I alive against all odds, I was also given someone extraordinarily special with whom to share this moment. For one afternoon, we had the most wonderful gift of all: a normal life. I felt a twinge of guilt.

With Doris proudly by my side, we marched arm-in-arm through the beautiful city of architectural jewels, made even more spectacular by the shimmering frost of winter. We crossed the Rhein Main River on the ancient Lowenbrucke (Lion’s Bridge), so named because of the golden medieval lions guarding the bridge at each end. From there we hiked up the steep mountainside to Kapellenberg (Chapel Hill), named for the tiny Catholic chapel that stood in the midst of vineyards.

Farther up the hill was the Festung Marienburg, a massive fortress that offered a panoramic view of Würzburg. The excitement was exhilarating! Every now and then, my eyes would get misty. Holding each other’s gloved hands, we skipped down the hill as the sun was sinking. It was quite romantic. I was so grateful to be alive and walking among the Würzburgers, who appeared to still enjoy life undaunted by the imminent cataclysm of a massive military defeat. Here, with Doris, I had a brief return to normal life.

Since my first combat mission in November 1942, death had been my constant companion. It was all around me, day and night. And now, here I was! Against all odds, I was not only alive and healing, I was about to explore a beautiful city with a wonderful young woman. Why me?

Doris took me to one of the medieval monastery wine restaurants for which Würzburg is famous. I believe it was the Julius Spital, established around ad 1300 as a hospital operated by monks. Six hundred and forty-four years later, the monks were still there, but now the Spital was a convivial, cozy wine restaurant—all dark wood and brass and copper and pewter that had been there for centuries.

Doris had saved her ration coupons from the time she had first come to see me at the hospital. As it turned out, they weren’t needed. After more than four years of Army chow, considering what was available in Germany in February 1945, we had what I considered a fabulous meal. Having been a combat trooper most of my service career, I had no concept of the harsh wartime privations the civilian population had to endure.

The waiters and the clientele were falling all over me. People volunteered to give up their table for us, and the waiters served us before anyone else. This privileged treatment delighted Doris no end. I suspect her bemedaled, wounded pilot was a bit of a trophy for her, and she relished it to the hilt. I wasn’t complaining. We had two bottles of Boxbeutel, and our conversation became quite animated.

Dinner was over. I leaned in close and asked, “What would you like to do now?” Doris replied, “Let’s find a hotel room”—and so we did. We took a room on the fourth floor above the restaurant and did what all lovers do, especially in wartime when you don’t know whether you will see tomorrow.

The Fire Bombing of Würzburg

Between waking and dreaming, I wallowed in the scent of Doris’s freshly washed hair and the creamy softness of her skin. I didn’t want to lose this moment by falling asleep. Her head was on my chest. I could feel her breath on my skin. Even in sleep, she had a satisfied smile on her face.

Something distracted me from my drowsy state. At first I chose to ignore the shrill, escalating, ear-piercing blast of an air-raid siren, denying the dreaded intrusion. I drew the comforter up over our heads. This couldn’t be happening! Not now!

Doris must have heard the sirens because she began to stir, not quite yet aware of what awakened her. Then, with a start, she sat straight up in bed. Terror filled her eyes. When the reality of what was happening sank in, she tore back the comforter and started to bolt. I grabbed her arm and pulled her back into bed. She fell into my arms. Moments later, we were clinging together, wrapped in the cocoon of our comforter. I could feel her heart racing with fear, yet she didn’t pull away.

In the distance, I could hear the terrifying drone of the approaching British Royal Air Force bombers. Still, Doris heard me clearly when I said, “Doris, I think we should stay up here. If we die, we die together; if we don’t, so much the better.” She responded with a deep lingering kiss just as the British started unloading death upon the city. Legend has it you never hear the shell that has your name on it, but not so with bombs. I think the Royal Air Force ditty from the Battle of Britain conveys this message best:

The Angels, they are a sing-a-ling-a-ling

They’ve got the goods for me.

The bells of Hell are a ring-a-ling-a-ling

For you but not for me.

Oh Hell where is thy sting-a-ling-a-ling

Oh Grave thy victory?

The bells of Hell are ring-a-ling-a-ling

For you but not for me.

We held each other tightly as our building shook and swayed. Horrifying explosions silenced screams as buildings all around us began to collapse. Shards of glass ripped through our comforter and cut our skin when our windows blew inward.

Hours later, the nightmare ended. We were badly shaken, but only scratched. As dawn broke, we could see fires and piles of rubble where buildings once stood through the smoke and dust-filled haze. The cries and moans of the injured and terrified were all around us. Already there were teams of people in the streets searching for anyone who might still be alive. Already they were removing bodies from the destruction.

The question neither of us dared to ask was whether anyone with whom we had enjoyed our evening meal last night was among them. Was it possible that only hours ago this city had been alive with its history and glimmering beauty? I tried to shield Doris from this horrible sight, but it was in vain. I did the best I could. I held her hand and led her through the carnage back to the safety of her home.

Refuge in a Basement

At the hospital, I had made friends with a Fallschirmjäger—a paratrooper—a really nice guy, about my age, who had caught a bullet in his spine. Surgery had left him limited in mobility from the waist up, thus he walked around quite stiffly. He had been studying engineering in the Ruhr, the industrial powerhouse of Germany, when he went into the service. I assumed he had volunteered because paratroopers, like pilots, were all volunteers. This was March 23, 1945. We both had a pass to go into town, and so we did. We went to the Julius Spital, minus Doris, for some good food and wine.

Around 11 pm, just as we were leaving, the air-raid sirens sounded. Having already both just experienced the previous air raid, we ducked into the nearest shelter inside one of the many downtown military hospitals. Like most air-raid shelters, it had a steel door, two inches thick, which was locked by pulling down two large handles—something like the bulkheads on a ship. The bombers were still on their way.

People came into the shelter from the street; doctors and nurses came down from the upper floors of the hospital. Then a bunch of medics carried in about seven patients in body casts all the way from their feet to their necks, legs spread apart. They were quadraplegics, we were told. They had suffered severe spinal injuries and/or were brain damaged. I had never seen anything like this before.

The medics propped them up against the wall of the shelter; there was no other place to put them. The rest of us—soldiers, doctors, civilians, and nurses—were already packed in as tightly as could be, so we stood pressed up against them. There wasn’t an inch to spare. When the shelter was filled to capacity, the steel door was locked.

This was the basement of an old building from the turn of the century. It had two small windows shaped like an orange section above our heads and level with the sidewalk outside. The atmosphere was so tense, you could smell the fear. The air-raid sirens came to a sudden halt, followed by the dreaded, ominous silence. All we could hear were whimpers and choked sobs.

Minutes later, the roar of hundreds of RAF bombers was directly over target—and boy, did they unload! The bombs were waltzing over Würtzburg. The bombs missed the shelter by mere inches! Violent explosions rocked the ground and shook the walls, breaking the windows. Flames flashed through the small windows over our heads. Some of the nurses became hysterical. Others sobbed. I thought about the men pressed against the wall, totally helpless in their body casts. I guess my stiff-backed buddy, the paratrooper, was thinking about them too, for he looked at them and then at me. I suspected he thought, “There, but for the grace of God, go I.”

A Hard Decision

The raid went on and on and on. New waves of bombers arrived overhead and unloaded death on the city. I had 21/2 years of combat behind me. I had flown 86 combat missions. I had been exposed to three weeks of hand-to-hand combat in the Soviet Union and had persevered reasonably well, but being confined in this small basement during an air raid gave me the willies. There was nothing we could do except wait—for death or survival.

My frustration transformed itself into a rage against the bombers overhead. I shouted imprecations to vent my fury. I felt great respect for all the people in Germany who had endured these raids night after night, for years on end, and still did not break. At this time, all things considered, I would rather have been at the front flying missions than cooped up in that rat hole. It was hell in the shelter.

At first I thought it was all those people jammed together, but then, on the sidewalk, from what we could see through the small window, it became like daylight. Then I realized—fire storm! The British were conducting a fire raid against Würzburg like the one in Hamburg. The city was ablaze from one end to the other. The temperature in the shelter was rising. Breathing became difficult.

It was so hot that people started to choke from lack of oxygen. Our building was on fire! We tried to open the steel door, thinking maybe we could get everybody out of the shelter and out on the street, but it was so hot we could not touch it. It began to change color, and then it glowed red from the heat. We had no other choice than to get through the small broken window. We boosted the nurses and females out the window, one by one. Next were the doctors and civilian men.

That left my paratrooper buddy and me and the men in body casts, who were now lying on the floor. They would not fit through the small window. They had no way out. If we left them there, the fire would roast them alive—an unspeakable, excruciating death. We asked them what they wanted us to do. We were both carrying Walther 7.65 automatics.

“Shoot us,” was the reply from those who could communicate. And so we did. It was one of the hardest things I had to do in my life, and that went for my buddy, too. I get tears in my eyes to this day when I think about it.

“When in Doubt, Firewall it!”

There was no time left. I was too short to reach up to the window. Besides, I had this useless arm. So I stood under the window, and my buddy stood upon my shoulders and climbed out. Then he lay on his stomach and reached down for me. He was a six-footer with rather long arms. I grabbed his left hand with my good arm. He grabbed me under the left shoulder and pulled me out to the sidewalk. As I got up, I looked around. It was a scene from Dante’s Inferno.

We were three blocks from the same Löwenbrücke I had crossed with Doris on an earlier and happier occasion. The surface of the road was on fire and melting. High-voltage cables snaked across the street arcing blue sparks. There were several time-delay bombs scattered on the surface of the street between us and the Löwenbrücke. The city was a raging inferno. There was no point in trying to return to the hospital. Most likely it was on fire like the rest of the city. Where to go?

“Let’s walk to Doris’s house. No use staying here. There might yet be another raid!” I said to my buddy. Looking at those time-delay bombs gave us pause, so I followed the old Luftwaffe axiom. “When in doubt, firewall it!” I yelled. “To hell with these bombs! Charge!”—and we dashed across the bridge.

Once across the bridge, we were on the outskirts of town and not too far from where Doris lived. We high-tailed it to Doris’s house. The roads were strewn with thermite bombs, some half burned and others unexploded. We arrived around 3:30 am, all out of adrenalin, dead tired and hungry. We banged and banged on the door before her father answered it, with a scared Doris and her mother peeking around from behind him. Due to the tearful begging of his daughter, I suspect, he finally allowed us in.

Doris fed us and put us up for the night. The next morning, my friend and I said good-bye to Doris and her family, thanking them for their refuge that terrible night. I had no idea, at that time, that it would be the last time I would see Doris until well after the war ended, when I returned to Germany a married man.

Return to Marian Hill Hospital

My friend and I went to the Kapellenberg and surveyed the city. I wondered why the British had destroyed it. Many had been killed. There were nothing but hospitals in Würzburg. There was no industry, and certainly there were no military installations. But I guess after Auschwitz and various other German projects, the Germans had it coming.

My buddy and I marched through the city and up the hill to Marian Hill Hospital. Clean-up details were busy clearing the rubble, and shops were open. You had to hand it to those Germans—they had lots of intestinal fortitude, and they shone in adversity.

Marian Hill Hospital had been badly hit but was functional. My room was still intact and I resumed my residence. During the air raid, a bomb had landed in the operating room. Professor Narath, who had done my nerve sutures and saved my left arm, had been operating at the time. He was killed.

The Allied armies advanced into Germany. The Third Reich was in its death throes. Chaos was everywhere. The SS and the Nazi Party faithful rounded up all able-bodied men for Armageddon. Fortunately, they left my hospital alone. I had seen some men strung up on lamp posts with signs on their chests: “I am a traitor. I refused to fight for the Third Reich!” The convulsions of a dying, evil force were everywhere. The final solution had come for Germany this time, and none too soon.

A Prisoner of the U.S. Army

On April 2, 1945, the United States Army entered the hospital and took me prisoner in my hospital room. Need I mention they encountered no resistance? We were herded into a truck and taken to a tennis court area enclosed by a cyclone fence, where we encamped under the open sky in the rain with no food, no shelter, and no cover. We were handed over to the Yugoslavian guards.

There were others, too. There were boys, about age 12—no doubt formidable members of the dreadful Werewolf (the loosely knit Nazi guerrilla movement). There were men in their early 70s, probably unwilling members of the last ditch Volkssturm (Home Guard), pressed into service by the party bosses. Then there were just plain men of all ages and description. We were under heavy guard by half-tracked vehicles with 20mm cannons.

April in Germany is not the greatest time of year. As a matter of fact, any time of the year in Germany is not so great—the climate being what it is. Spring in Germany comes once on a Thursday afternoon between 3 and 5 pm, I am told. We spent three days and nights on the surface of this tennis court in a cold rain. I do not recommend being a prisoner of war, especially not when you have just come out of a hospital—it does little for your general well being. “But them’s the breaks” when you lose a war. Better not to start one unless you really need one.

The U.S. Army loaded us into semi-trailers—100 men per semi (have you ever looked into an open sardine can?)—and conveyed us to Worms, an ancient city on the Rhine. There we were deposited in a sea of mud enclosed by barbed wire. We lived on five hardtack and a pint of water per day.

Adding to our delight, the soldiers threw rocks at us so we would get mad and charge them so they could legally fire on us. Some of the German prisoners were dumb enough; now they don’t have to worry about income taxes anymore.

Like I said, I don’t recommend being held prisoner. But “adversity builds character,” ‘tis said. I built a lot of character in those days. Here I was, 50 miles from my hometown, Wiesbaden. I had not had any mail from my mother in nine months. The entire country had come to a halt—no trains, no mail, no phone, no gas, no heat, no water, no food—no nothing. I had no idea whether my mother was dead or alive, or whether our apartment house was still standing. Here I was, so close yet so far, unable to contact my mother and not knowing where I would be sent next.

Relocated to France

Having been kept in these exquisite accommodations for three weeks, our numbers had been reduced somewhat by those who had expired, environmental conditions being what they were. We were then loaded into cattle cars together with cartons of C-rations, which to me were like manna from heaven. The doors were locked, and we were on our way to God knows where.

That turned out to be southern France—as far south as you can go in France. This was the Camargue—a desolate region up in the hills, northeast of Marseille, composed mostly of red sand which the mistral, a hot wind from the Mediterranean, blows into your face day and night.

While our train chugged through France, the French threw rocks at us when we stopped. Couldn’t blame them. We were the loser, and from what I hear the Germans had not been very cordial when they occupied France. I was one of those guys who dodged bullets in the Soviet Union when everyone else was a conquering hero in France. When I finally made it to the Western Front, the invasion had started, and I picked up where I had left off—dodging bullets. But then, I had volunteered for combat. Never volunteer; if something happens to you, you only have yourself to blame.

Epilogue

While he was a prisoner of war held by the Americans, Jack Hildebrandt’s badly injured arm kept him from hard labor and in the office of Sergeant Joe Finklestein from the Bronx. The two formed a fast friendship, and the end result was that Jack learned American English—with a Bronx accent! Once back on home soil in Wiesbaden, Germany, Jack’s perfect American English landed him a job with the U.S. Air Force Europe Criminal Investigation Division (USAFE CID).

Jack’s lifelong dream to become an American citizen came true in July 1950. After moving to California, he again landed a civil service job with the Air Force and married an American woman. His German heritage and perfect English brought him right back to where this all started—Germany—thus beginning an odyssey as a Cold War spook.

Being forever loyal to his combat buddies, he tried in vain to find the crew he never got to say “goodbye” to. His quest to find his wartime love, Doris, also ended in sadness. Months went by before he finally found Doris, tragically incarcerated in an insane asylum. After a brief visit, he returned months later, only to be told she had died. Although suicide was never mentioned, he understood what had happened; Doris’s death haunted him for the rest of his life.

Jack achieved his lifelong dream, and for 35 years he faithfully served his adopted country as a civil servant in the USAF. For the rest of his days he lived in Palo Alto, California, a happy man. A popular member of the Commemorative Air Force’s Golden Gate Wing, Jack’s story made him one of their more popular speakers. He passed away in May 2010.

Interesting look into the life and wartime experiences on someone on the other side. Thanks for sharing this article.

An amazing story! Thanks!

So sad about Doris. She saved his life, but he couldn’t save hers. PTSD got her into the asylum.