By David A. Norris

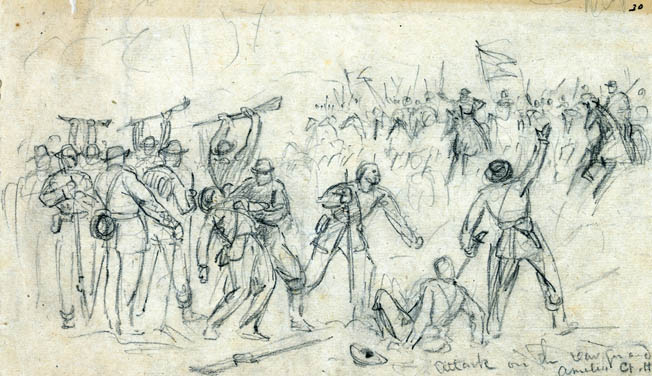

Four hundred Confederate sailors and marines, their small arms loaded and ready, awaited their orders. Some men had their cutlasses within easy reach. Their commander, Navy Flag Officer John Randolph Tucker, watched as the enemy approached within pistol shot. Tucker, excited but confused, shouted, “Prepare to repel boarders!” These Rebel tars were in strange waters indeed on April 6, 1865. Far from the briny blue Atlantic, Tucker’s quarterdeck was a spot of high ground overlooking a small Virginia stream called Sayler’s Creek. Wading and splashing through the creek, the Federals’ boarding party was the vanguard of Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright’s VI Corps infantry.

The odd spectacle of Wright’s foot soldiers facing cutlass-wielding Confederate sailors reflected the extreme circumstances leading to the Battle of Sayler’s Creek. After months of siege warfare, the Army of Northern Virginia was driven from its fortifications around Richmond and Petersburg at the beginning of April. General Robert E. Lee’s army, cast from its moorings just as surely as Tucker and his seadogs, reacted to a whirlwind of disasters unfolding around it. The men needed time to catch their breath, reorganize their scrambled units, and forge new plans in the quickly unraveling Confederacy. And time was the one thing that Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his cavalry leader, Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan, intended to deny them.

Lee’s Fateful Message to Davis

After the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864, Grant had proved to be a different kind of general for the Union’s Army of the Potomac. There were no more long stretches of idling in camp and no more withdrawals after defeats. Constant pressure punctuated with frequent attacks kept Lee’s army hemmed in against Richmond. The Confederates settled in behind a complex and steadily lengthening system of earthworks stretching more than 20 miles south from Richmond to Petersburg. For months, they held out as Union assaults failed to make a lasting breach of the defenses. Then, on April 1, Sheridan’s cavalry and Maj. Gen. G.K. Warren’s V Corps poured through a break in the Confederate lines at Five Forks. The sudden Union surge threatened the Southside Railroad, Lee’s last link with supplies from the south, as well as Petersburg itself.

After previous Union victories, the Confederates had always managed to extend or adjust their lines. After Five Forks, however, this was no longer possible. Lee telegraphed President Jefferson Davis on the morning of Sunday, April 2, “I see no prospect of doing more than holding our position here till night. I am not certain that I can do that. If I can I shall withdraw tonight north of the Appomattox. I advise that all preparation be made for leaving Richmond tonight.”

Lee’s fateful message reached Davis at 10:40 am, when a courier found him attending a service at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. Opening the message, Davis stood up. Richmond socialite Sallie Brock Putnam heard whispers flying through the congregation when the president “walked rather unsteadily out of the church.” Soon, the sexton moved among the pews, summoning other government officials. Those who remained worried about the mysterious but obviously dire news that had driven Davis out into the street. Their fears were confirmed when the minister ended the service with an announcement that Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, commander of the Confederate troops at Richmond, was ordering all of his men to report to duty as soon as possible.

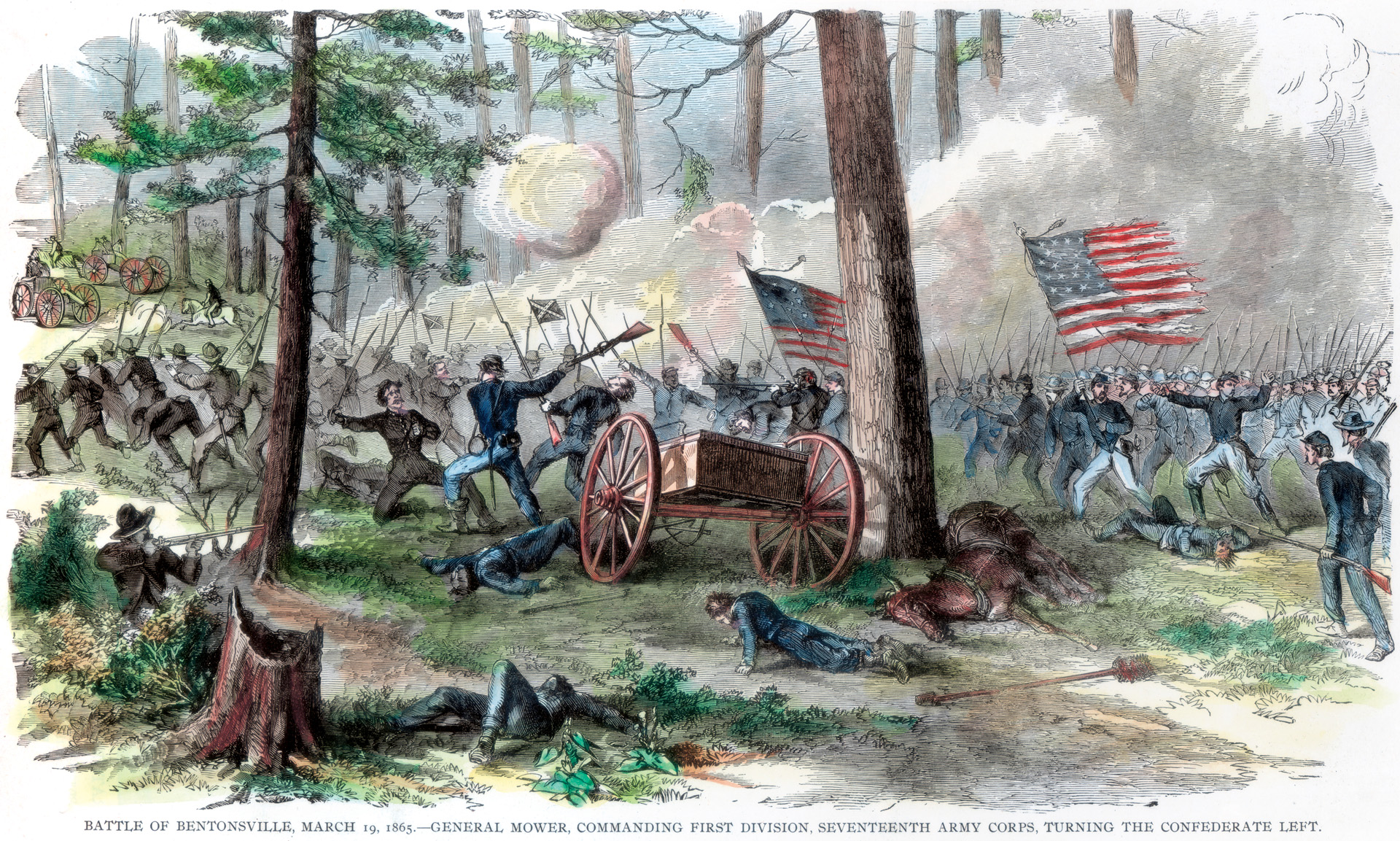

With the fall of Petersburg, Richmond was doomed. Lee had to abandon the shelter of his entrenchments and take his outnumbered and outgunned army into the open. In a dispatch sent to Richmond later on April 2, Lee informed Davis that his troops would leave Petersburg and Richmond that night. Lee’s only chance for keeping a Confederate army in the field was to unite his men with General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of the South in North Carolina. Johnston commanded a hodgepodge of survivors of the battered Army of Tennessee as well as garrison troops and scattered field commands drawn in from Georgia and the Carolinas. This new army had lost the Battle of Bentonville in Johnston County, North Carolina, on March 21. But, Johnston’s force was still together after retreating in good order.

Ewell led the forces out of Richmond. Behind them, mobs of looters broke into civilian shops and government storehouses. Fires set under Army orders to destroy government-owned supplies quickly spread out of control, melding with other fires started by looters. Smoke and flames swirled from a growing conflagration that consumed much of the capital city.

Tucker’s Mixed Unit

Major Generals Joseph B. Kershaw and Custis Lee led their divisions of Ewell’s forces to the south bank of the James River across a pontoon bridge. Then they turned west to follow the Genito Road before picking up the path of the Richmond & Danville Railroad. Moving to the north of Ewell’s infantry on a roughly parallel route was a long wagon train. Ewell’s command included a mixed lot of garrison troops and part-time emergency units comprised of government clerks and other employees. Accompanying them was Tucker’s uniquely mixed unit.

For some weeks, Tucker had led a force of sailors and marines who manned batteries at Drewry’s Bluff. Most of his men came from ironclads or other vessels lost over the last few months when the ports of Savannah, Charleston, and Wilmington fell to the Union. Tucker’s unit was styled the Marine Brigade. Amid the despair and confusion afflicting the army, the soldiers found the Marine Brigade an amusing spectacle. Tucker’s men answered their officers’ commands with the traditional maritime reply of “Aye, aye, sir,” inducing the foot soldiers to call them the “Aye-Ayes.” Officers gave nautical-style commands, ordering the men to march to port or starboard rather than left or right. They wore naval uniforms, and some of the men carried naval cutlasses.

The largest contingent of Confederates included the troops under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, who streamed out of the Petersburg works. They headed west, marching roughly parallel to the north bank of the Appomattox River. Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon commanded the rear guard. On a separate road went another massive wagon train. Another part of the Southern army, under Maj. Gen. William Mahone, evacuated the fortifications north of Petersburg, leaving behind the heavy artillery they had manned for two years. Mahone marched on a course that would merge his troops with the main army.

When the Union Army commanders learned that the Confederate works around Petersburg were empty, part of the army moved to take possession of Richmond. Grant sent five corps of infantry and Sheridan’s cavalry to catch up with and delay the retreating Rebels. Swift pursuit was an ideal job for Sheridan’s cavalry. Early in the war, the Confederate cavalry far outclassed the Union Army’s horsemen. Gradually, however, the Union cavalry gained polish and professional skill, while the superiority of the Southern cavalry faded. Southern cavalry horses were tired and short of food; their dire condition was aggravated by the sudden and disorganized retreat from Petersburg. Lee’s overstretched cavalry could little to interfere with Sheridan or his three division commanders, Brig. Gen. Thomas Devin and Maj. Gens. George Crook and George Armstrong Custer.

The South’s Starving Army

Events were spinning out of control for Lee. Perhaps 30,000 men were left under his command after the final battles around Petersburg. Including the two massive wagon trains, they were divided into five major sections. He had to keep ahead of Sheridan long enough to unite his scattered troops and also find some way of feeding them. To meet both objectives, Lee ordered his troops to rendezvous at Amelia Court House, 40 miles west of Richmond. Because this spot was on the still operating Richmond & Danville Railroad, orders went out to transport some of the government’s reserve food and supplies to Amelia Court House. With the army resupplied, the troops would march south toward North Carolina.

Sheridan’s cavalry dogged the Confederates with constant skirmishing and a large clash at Namozine Church on April 3. Exhaustion, lack of sleep, and hunger plagued Lee’s troops. Private Carlton McCarthy of the Richmond Howitzers remembered marching all day on April 3 and 4. Awakened before dawn on April 5, his comrades moved out “stumbling, bumping against each other, and sleeping while they walked.” At any brief halt, the men fell to the ground and slept until their officers woke them again. “Those first on their feet,” wrote McCarthy, “went stumbling on over their prostrate comrades, who in turn would be awakened.” After long hours of marching, McCarthy’s unit learned that their division had issued its last remaining rations. No food could be found, except by robbing the horses. Each man was issued two ears of corn originally intended as horse feed. McCarthy recalled, “It was parched in the coals, mixed with salt, and eaten on the road. Chewing the corn was hard work. It made the jaws ache and the gums and teeth so sore as to cause almost unendurable pain.”

Hungry Confederates straggled into Amelia Court House on April 4 and 5. But, although some ordnance shipments had arrived, there was no food. In the last hours before leaving Richmond, the necessary orders to the Commissary Department had miscarried, and 350,000 rations slated for transfer to Amelia Court House were never shipped out of Richmond. Neither did orders reach Danville or anywhere else from which stockpiles of commissary supplies could have been shipped.

Lee had intended only a brief halt at Amelia Court House. Now he was forced to wait. He issued an appeal to local farmers asking for “such meat, beef, cattle, sheep, hogs, flour, meal, and provender that can be spared.” Soldiers were sent out with wagons to fill with what supplies they could impress, but little could be found in the sparsely populated surroundings. While the foraging parties continued their fruitless work, the delay allowed Union infantry to close the gap between the two armies.

After months of hard work and insufficient feed, the army’s draft animals were nearly broken down during the forced march to Amelia Springs. Artillery horses were in such pitiable shape that they could carry only a fraction of the army’s ordnance stocks. Nearly 100 caissons, loaded with nearly three-quarters of the Army of Northern Virginia’s artillery shells, were set afire and blown up, leaving gunners with only the limited supplies of ammunition packed in their limbers.

Another disaster struck the Southern army that day. Brig. Gen. Henry E. Davies of Crook’s division intercepted the wagon train from Richmond before it could reach the Confederates. Davies destroyed 200 wagons, ambulances, and caissons, dealing another heavy blow to an enemy that was already dangerously low on supplies. Also on April 5, the Confederates discovered that their route to the south was blocked by Union troops at Jetersville, seven miles to the southwest. Lee decided against forcing a way through the enemy entrenchments. Instead, he moved toward the west, hoping to regroup and find supplies at Farmville, 25 miles away.

The Last Confederate General Killed in Action

The Confederates broke camp well before dawn on April 6, and for a time their move went undetected. Soon, however, the Federals resumed the chase. II and VI Corps followed Lee down the Deatonsville Road. At 8 am, the 1st Maine Cavalry was mounted and on the move. Brigade commander Charles H. Smith was heard to say, “Today will see something big in the crushing of the rebellion.”

Custer, Devin, and Crook followed a parallel course to the south of the Rebels, aiming to draw ahead and block their path until the foot soldiers could catch up. As the troopers rode over high ground, they could see Lee’s train moving along through gaps in the woods. Mile by mile, the bluecoats drew ever closer to the enemy wagons. For the soldiers of both sides, marching feet, trampling hooves, and rolling wagon wheels churned the rain-softened Virginia soil into mud. The soggy ground made for a fatiguing march for the Federals, but the rainfall affected the Confederates far more as it slowed the escape of their dwindling number of supply wagons.

Longstreet led the way for the Confederates, heading toward Farmville along the Deatonsville Road. Behind Longstreet’s men were Mahone’s followed by those of Anderson and Ewell. Gordon’s commandserved as a rear guard and protection for the wagon train. It was imperative that the army keep moving, and push well ahead of the Union forces lest the Confederates find their way blocked once again.

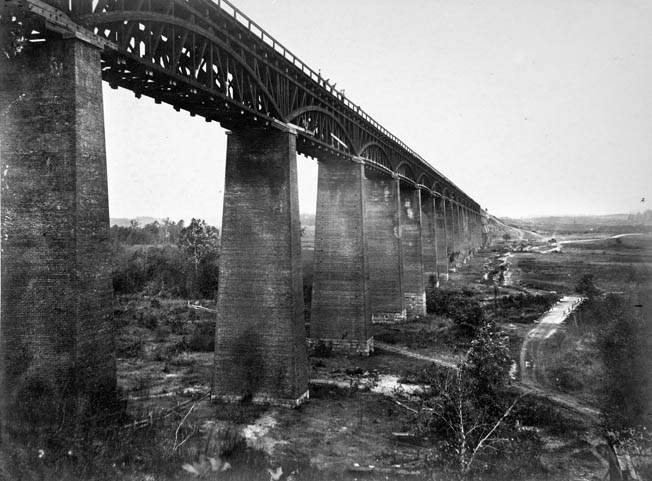

Disturbing news reached Longstreet that 900 Union soldiers were ahead of them, intent on burning the High Bridge. Destruction of the 2,500-foot span of the Southside Railroad, which crossed the Appomattox River, would block the way to Farmville. Longstreet ordered Maj. Gen. Thomas Rosser’s cavalry to protect the bridge. Rosser stopped the Federals in time to save the span, capturing most of the raiding party. One of Rosser’s officers, Brig. Gen. James Dearing, was mortally wounded in the battle. Dearing would be the last Confederate general killed in action during the war.

Unprotected Wagons at Sayler’s Creek

Union scouts spotted the Confederate wagon train and the accompanying troops a few miles west of Amelia Court House near the small community of Deatonsville. Under Sheridan’s plans, if one division hit the Rebels from the south, the others were to move to the left and try to get in front of the enemy, striking them at some weak point in the line. Crook’s division attacked late in the morning, when the wagon train was near Holt’s Corner. About 11:30 am, Smith ordered the 1st Maine Cavalry to leave the road, form a column of fours, and charge through the woods to hit the enemy train. Only a few steps from the road, the troopers found themselves in a swamp, their horses sinking in the ground to their knees at every step. Getting out of the swamp forced the horsemen to ride single file along the few navigable pathways.

Lieutenant Colonel Jonathan P. Cilley, too impatient to wait until the entire regiment emerged from the swamp, ordered an advance. Their way blocked by a fence they could not ride over, the men dismounted. More troopers joined them, but they were in the open and exposed to heavy fire, while trees and woods sheltered the Confederates guarding the wagons. Unable to accomplish anything, Cilley’s regiment pulled back. Elsewhere, the rest of Crook’s horsemen also found the Rebel wagons well protected. Devin and Custer moved to the west while Crook remained to distract the Confederates.

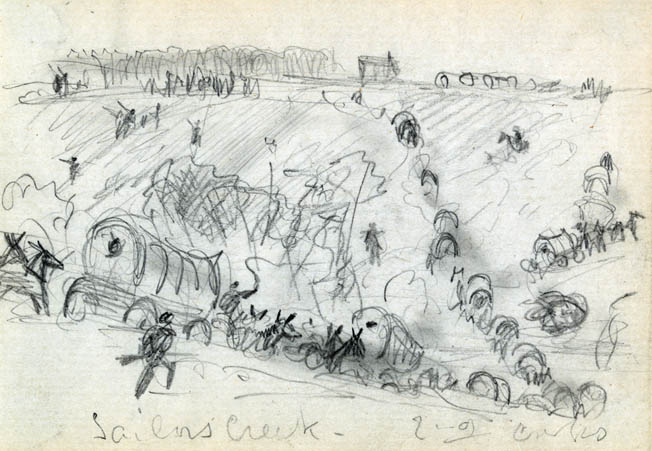

While Anderson fended off the enemy cavalry at Holt’s Corner, some of the Confederate wagons were sent ahead to join Longstreet. During the delay caused by Crook’s attack, a gap of two miles had grown between Anderson and the rest of the column. The wagons were rolling unprotected between the vanguard and rear of the army. Anderson’s troops resumed their march, reaching Little Sayler’s Creek, a small but troublesome stream with steep banks 50 miles west of Richmond. Although often spelled “Sailor’s” Creek, the stream actually was named for a local settler named Sayler. After the recent rains, the creek was overflowing its banks into the surrounding bottom lands.

Custer Strikes

Riding to get in front of Anderson, Custer’s troopers spotted the nearly unprotected wagon train. Colonel Alexander C. M. Pennington’s brigade hit the wagons as they rolled down the road, sweeping through a thin skirmish line of guards and captured the train. Another three supply wagons were lost, along with, 800 draft animals, 10 guns, and a number of prisoners.

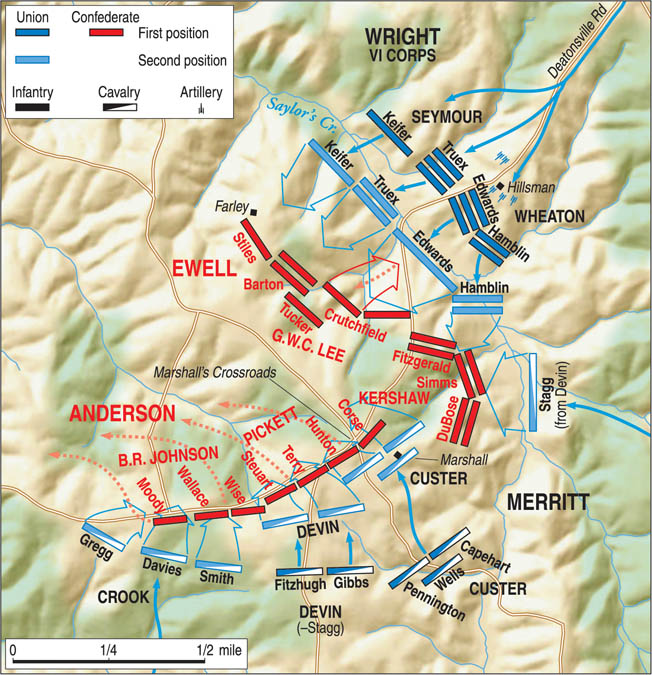

One mile past Little Sayler’s Creek, Anderson came within sight of Custer’s troopers and the smoke of burning supply wagons. Anderson halted at Marshall’s Crossroads, his two divisions taking up positions north of the Deatonsville Road and throwing together a line of entrenchments. After some shuffling of units, Maj. Gen. Bushrod Johnson held the right and Maj. Gen. George Pickett held the left. Meanwhile, the main body of the Confederate Army was several miles west at Rice’s Station, a stop on the Southside Railroad. Longstreet and Lee were unaware of the peril facing the detached portion of the army, and the beleaguered Anderson was unable to get word to them.

While Anderson prepared for battle, Ewell and Gordon were still some distance behind. Ewell ordered the remaining wagons to leave the Deatonsville Road near Holt’s Corner. They took a side road that led to the Jamestown Road, which ran alongside the Appomattox River on the route to Farmville. Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys’s II Corps was close behind Gordon and the Confederate rear guard, and Wright’s VI Corps was following Humphreys. Maj. Gen. Frank Wheaton, one of Wright’s division commanders, reported that his troops pushed with “the greatest haste, much of the march over plowed fields and rough ground.” To forestall the capture of the wagons, Gordon followed the train. Ewell never learned that his rear guard had left the Deatonsville Road, assuming that Gordon still shielded him.

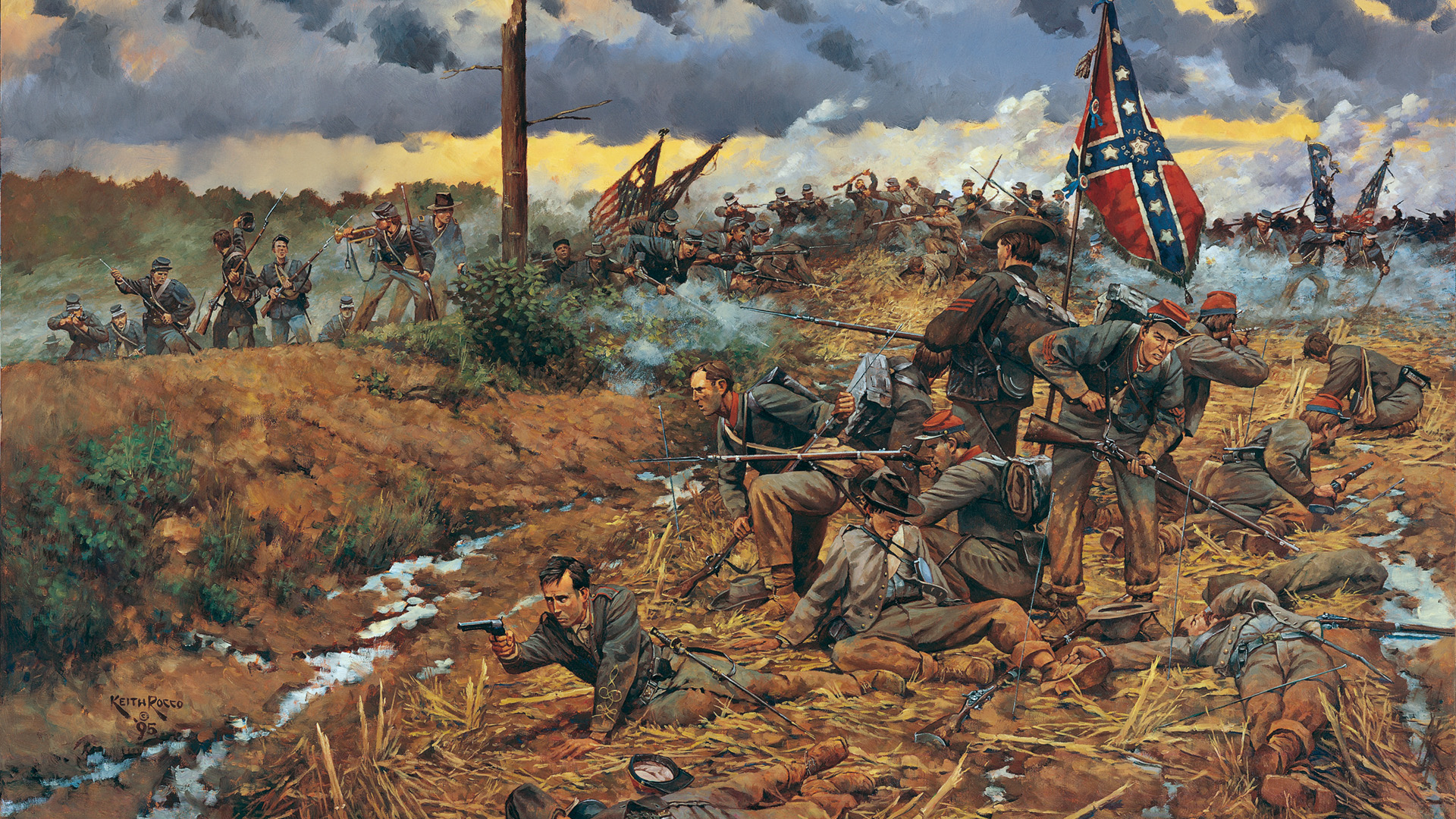

Humphrey’s troops turned north to follow Gordon, but Wright’s VI Corps stepped into their place to confront Ewell. Learning of Wright’s approach, Ewell halted west of Little Saylor’s Creek. On high ground overlooking the stream, the Confederates prepared a hasty defensive line running perpendicular to and across the Deatonsville Road. Little Sayler’s Creek was about 300 yards in front of the Confederates, with brush pines between and a cleared field beyond it. On the left was Custis Lee, with the Richmond troops, and on the right was Kershaw. Between and slightly behind them, the Marine Brigade waited in reserve.

“A Most Effective Fire”

Accompanying Ewell was Colonel Stapleton Crutchfield, who had become famous as Stonewall Jackson’s chief of artillery during the Shenandoah Valley campaign. Following the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863, Crutchfield was seriously wounded in the friendly fire that fatally wounded Jackson. After Crutchfield returned to duty, he commanded a battery of the Richmond defenses until the capital was evacuated. Now his heavy artillery brigade was attached as infantry to Custis Lee’s division.

While Ewell’s men waited, Major Andrew Cowan readied 20 guns of VI Corps’ artillery brigade on high ground near the Hillsman house. At 5 pm, Cowan’s guns opened up what the major called “a most effective fire” at a range of about 800 yards. Cowan reported later that “prisoners stated that it was the most terrific fire they were ever exposed to.” All of Ewell’s guns had been dispatched with the wagon trains, and the Confederates could do nothing except lie down and let the enemy shells pass over them. Cowan’s only casualties were two wounded gunners.

Picket’s Regiment Collapses

West of Sayler’s Creek, Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt arrived to take command of the divisions of Custer, Devin, and Crook. Merritt and VI Corps had the Rebels hemmed into an open triangle that pointed to the east. Anderson’s men, facing south toward Merritt’s cavalry, formed the southern leg of the triangle. Facing northeast toward VI Corps, Ewell’s men formed the opposite side. Although the two Confederate forces were not far apart, there was a gap of several hundred yards between Anderson’s left and Ewell’s right. The base of the triangle was open to the west, but the best escape route was blocked by Crook’s cavalry. Brig. Gen. J. Irvin Gregg’s men, dismounted, held the Deatonsville Road. Also dismounted, the 1st Maine Cavalry and the rest of Smith’s brigade were deployed to Gregg’s right. Davies’s brigade waited on horseback.

While Johnson and Pickett turned back several attacks by Merritt, Ewell rode a mile to the rear of his line to confer with Anderson. The latter proposed trying to break through the Union cavalry while Kershaw and Custis Lee held off VI Corps. Meanwhile, Anderson launched an attack, but the effort failed and the men were driven back to their entrenchments. Ewell and Anderson parted, each riding back to his troops.

About 5 pm, Merritt’s divisions pushed against the Confederate line along the Deatonsville Road, while Custer broke though Pickett’s division at Marshall’s Crossroads. Hardest hit were two commands on Pickett’s left, those of Brig. Gens. Montgomery Corse and Eppa Hunton. Both generals were taken prisoner along with a large portion of their men. Elsewhere, Picket’s regiments crumbled away.

A Counterattack Too Far

Without Pickett’s division in place, Bushrod Johnson came under fire on his left. Crook’s dismounted men turned Johnson’s right and rushed into the entrenchments, while Davies’s brigade charged on horseback and rode into the enemy works. Beset on their front and both flanks, Johnson’s brigades broke. Many of Johnson’s men reached safety with the main body of the army, but the greater portion of Pickett’s division was cut off and captured. Another 2,600 Confederates, 300 wagons, and 15 guns fell into Union hands.

As the Union cavalry attacked at Marshall’s Crossroads, Wright’s bombardment lashed the Rebels at Little Sayler’s Creek for half an hour. When the big guns ceased fire, the divisions of Truman Seymour and Frank Wheaton stepped forward, pushing into the flooded bed of the creek. The 7,000 Federals slogged through water up to four feet deep, carrying their muskets and cartridge boxes high above their heads.

On the Union right, Wheaton’s men moved in a broad, single line to cover as much of the front as possible. Their advance was irregular and disordered because of the swampy terrain. Lt. Col. John Harper of the 95th Pennsylvania reported that at the bank of the stream “some little delay took place, it being difficult to cross in some parts.” Staff officer Lt. Col. Miles L. Butterfield noted that Wheaton’s division shifted some distance to its left to find a fordable passage of the creek. Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Hamblin’s brigade, on Wheaton’s extreme left, crossed the stream, climbed onto the opposite bank, and reformed their ranks before hitting the Confederate line.

Some distance to Hamblin’s right, Colonel Oliver Edwards’s brigade crossed the creek and moved headlong toward Custis Lee’s division. To their left, Commodore Tucker was within sight of the approaching Federals and ordered his men into action. Holding their fire until the enemy was within 100 yards, the Confederates delivered two volleys that broke up and threw back the Union advance. The retreating Yankees also took friendly fire from the guns near the Hillsman House.

Carried away by the sight of their fleeing foes, some of Ewell’s men counterattacked, Crutchfield leading his former artillerists. The jubilant Confederates chased their enemies as far as the bank of the creek. Lt. Col. Joseph C. Hill, commander of the 6th Maryland Union Infantry, and several of his men were captured. The countercharge soon went too far. Now far from their entrenchments, the Confederates were within easy range of case shot hurled from Cowan’s guns. Some men of Edwards’s brigade were armed with Spencer rifles, and they poured in a concentrated and rapid fire. Those Confederates who could rushed back to their line. Among the dead left behind was Crutchfield, killed by a bullet through his head.

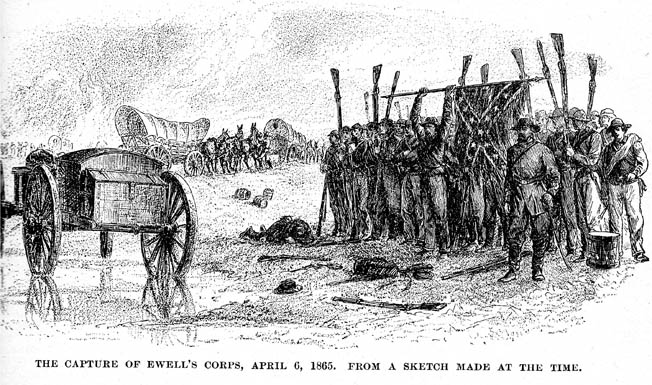

Ewell Surrenders to a Sergeant

Wright’s troops readied themselves for another charge. This time, Colonel William S. Truex’s brigade got behind Custis Lee and turned his left flank. As Lee’s men scattered, more Union troops overlapped Kershaw’s right and got behind him. Nearly surrounded, a few of Kershaw’s men got away as their formation disintegrated. With Pickett’s left flank broken and scattered at Marshall’s Crossroads, the way was open for Merritt’s cavalry to attack Ewell’s now isolated corps from the rear. Above Little Sayler’s Creek, the Confederates saw blue-coated infantry engulfing their front and flanks and enemy cavalry rushing in from behind.

Ewell saw that further resistance was hopeless. Twenty years later, a Union veteran writing for the National Tribune stated, “I might add that Ewell came near losing his life while looking for an officer of equal rank to surrender to.” Colonel Thomas S. Allen of the 5th Wisconsin reported that Ewell approached Sergeant Angus Cameron, in command of a squad of five men in the regiment’s skirmish line. Ewell asked Cameron if there was an officer present. No one of higher rank was on hand, so the Confederate lieutenant general surrendered the remnant of his corps to a Union sergeant.

Soon after the surrender of Ewell and his staff, wrote Allen, “a squad of cavalry came up and claimed the prisoners and took possession of them.” Elements of Custer’s cavalry claimed to have captured Ewell, and Ewell claimed that he had surrendered to cavalry officers. Amid a flurry of competing claims, Cameron saw his distinction of capturing a lieutenant general fall into dispute, but he was partially placated by being promoted to second lieutenant after the battle. Taken prisoner with Ewell were about 2,800 men including five generals: Kershaw, Dudley M. DuBose, James P. Smith, Seth Barton, and George Washington Custis Lee.

“Have You Got Gunboats ‘way Up Here, Too?”

After the rest of Ewell’s command was captured or scattered, the Marine Brigade still held on. No orders to withdraw ever reached them. Later, Tucker drily explained that “he had never been in a land battle before, and that he had supposed that everything was going well.” The steadfast discipline and determination shown by the Marine Brigade impressed soldiers of other commands, blue and gray. Union Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour wrote that they “fought with peculiar obstinacy.”

Informed by an officer that one Rebel unit was still fighting, a disbelieving Brig. Gen. Joseph Warren Keifer rode out to see for himself. He found the Marine Brigade by accidentally running into them. Thinking quickly, Keifer pretended to be a Southern officer and ordered them forward. The sailors followed Keifer for a short distance, but became suspicious. One man, close to Keifer’s horse, raised his musket to fire, but Tucker knocked the barrel aside.

Keifer returned with a white flag, accompanied by a Confederate officer who confirmed that Ewell and the rest of his men were prisoners. At last, the Marine Brigade surrendered. One of the Yankees, surprised at seeing captives in naval uniforms, asked, “Good heavens! Have you got gunboats ‘way up here, too?” Some of the naval officers broke their swords rather than hand them over to their captors, but Tucker handed his sword over to Keifer. Years later, the Union general returned the sword to Tucker.

Gordon’s Withdrawal

Gordon, in command of the army’s rear guard, sniped and sparred with Humphreys’s II Corps all day. With Gordon was the cavalry of Maj. Gen. William Henry Fitzhugh Lee. Another son of the commanding general, he was known as Rooney Lee to avoid confusion with a cousin, Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee. When the VI Corps attacked, Gordon was about two miles downstream from where Ewell was overrun. At this place, called the Double Bridges, the Jamestown Road crossed Little Sayler’s Creek and Sayler’s Creek just above their confluence. With two narrow spans surrounded by soft, soggy ground, the Double Bridges was a tight bottleneck to squeeze through with a retreating wagon train. Humphrey’s corps was fast approaching.

The two armies confronted each other near the Double Bridges on the Lockett Farm. Gordon arranged his men east of the creek, while behind him the drivers tried to get their wagons out of danger. The Federals formed on a rise behind the Lockett House. Maj. Gen. Nelson Miles’s division held the Union right and Maj. Gen. Gersham Mott held the left. Soon the Federal skirmishers approached, taking cover when the Virginians opened fire and the main battle line came within sight.

Gordon’s men fell back, taking cover behind the wagons. As the enemy pushed in the flanks and front, Captain Lorraine F. Jones shouted, “Boys, take care of yourselves!’” Jones then planted himself against a pine, and, as his men rushed by him, emptied every chamber of his revolver at the enemy and then reluctantly make his way down the hill. Gordon managed to hold on until dark. He got away with part of his force but at the cost of abandoning the wagon train. The Confederates lost another 1,700 prisoners along with 300 supply wagons and 70 ambulances at Lockett’s Farm and the Double Bridges.

‘My God! Has the Army Dissolved?’

Meanwhile, the advance of the Army of Northern Virginia was only a few miles east of Farmville. Lt. Col. Charles S. Venable found Robert E. Lee riding with Mahone and delivered the bad news that the Federals had captured the supply train. Lee replied, “Where is Anderson? Where is Ewell? It is strange I can’t hear from them.” Then Lee said to Mahone, “I have no other troops. Will you take your division to Sailor’s Creek?”

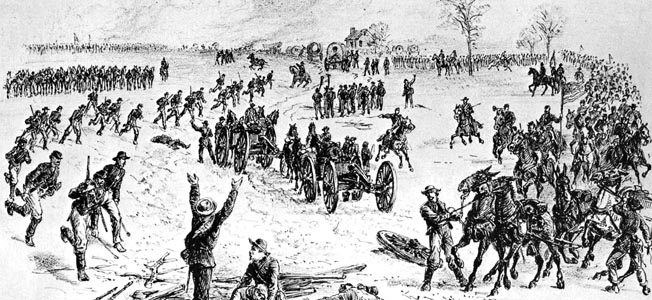

The three officers then rode back toward the battlefield. When they reached the top of a rise overlooking Harper’s Farm, Mahone saw that “the disaster which had overtaken our army was in full view, and the scene beggars description—hurrying teamsters with their teams and dangling traces (no wagons), retreating infantry without guns, many without hats, a harmless mob, with the massive columns of the enemy moving orderly on. At this spectacle, Lee straightened himself in his saddle and, looking more the soldier than ever, exclaimed, as if talking to himself, ‘My God! Has the army dissolved?’”

Mahone assured Lee, “No, general, here are troops willing to do their duty.” Lee replied, “Yes, general, there are some true men left. Will you please keep those people back?” As Mahone prepared his division to make a stand, some of the fleeing soldiers halted and gathered around Lee, who was on horseback holding a battle flag. Mahone took the flag from the commander and carried it to his troops. Blocking further Union advances and providing a rallying point for the scattered soldiers streaming from the battlefield, Mahone temporarily stopped the torrent of disasters besetting the army. In all, the Union Army had captured nearly one-quarter of the Army of Northern Virginia. Besides losing 7,700 men as prisoners, the Confederates lost another 1,100 men killed or wounded. Eight generals, including Ewell, were captured. Total Union losses were only 1,180.

Defeat of the Confederacy at Appomattox

Late on the night of April 6, Lieutenant John S. Wise, a courier sent by Jefferson Davis, went looking for Lee. It was well past midnight when he located the commander. Lee stood next to an ambulance, in which an aide sat writing by lantern light. On the ground a camp fire of fence rails was burning low; a distracted Lee stared into the burning embers. Wise reported that Davis wanted news about Lee’s plans. “Have you any objective point, general, any place where you contemplate making a stand?” asked Wise. “No,” replied Lee. “I shall have to be governed by each day’s developments.” Then Wise heard Lee say, a touch of resentment raising his voice, “A few more Sailor’s Creeks and it will all be over.”

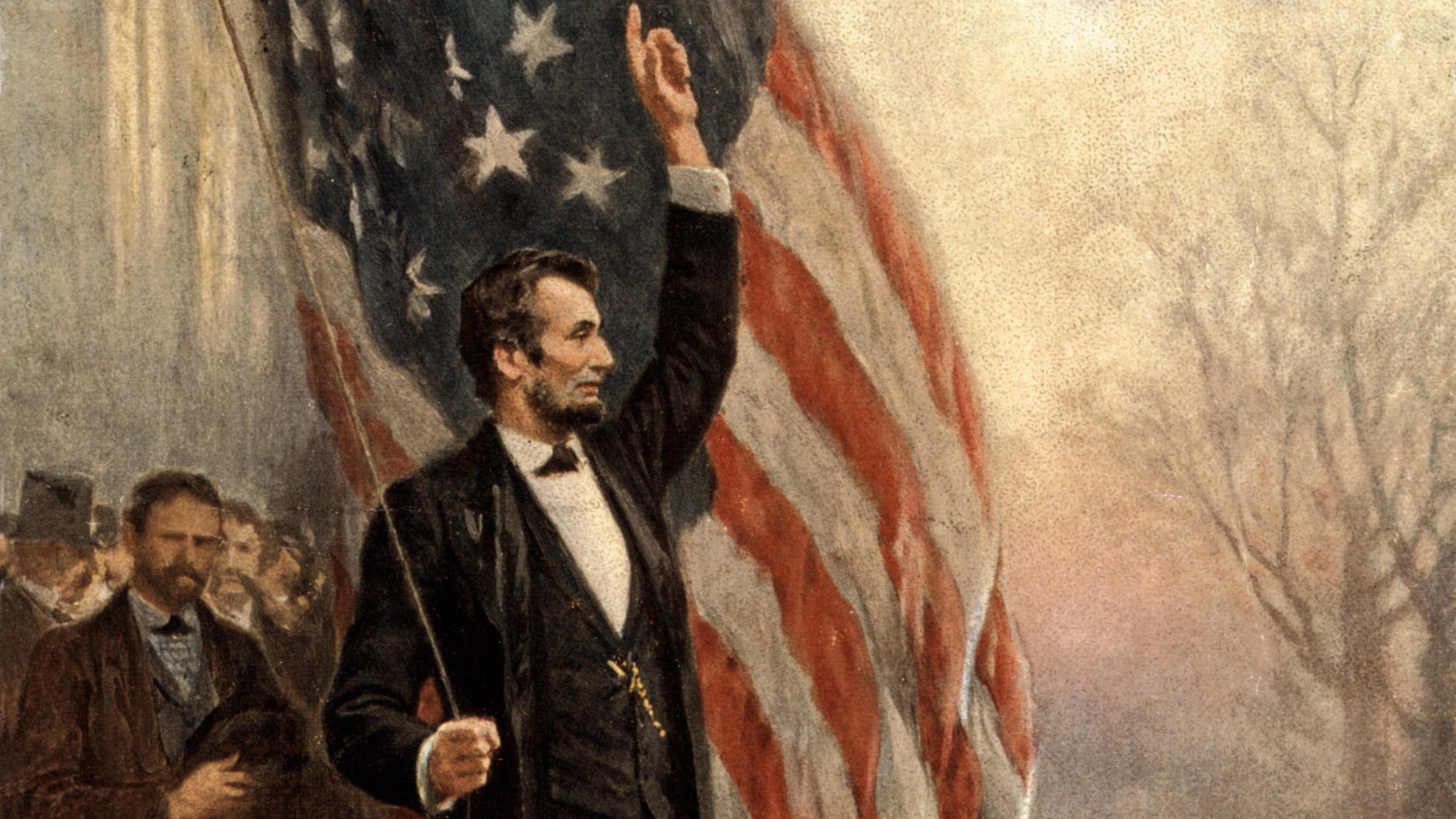

About that same time in the Union camps, a confident Sheridan reviewed the day’s events. He wrote Grant late on April 6, “If the thing is pressed, I think that Lee will surrender.” After Lincoln read the battle reports and Sheridan’s statement, he ordered Grant, “Let the thing be pressed.” Three days later, the much diminished Army of Northern Virginia was trapped at Appomattox Court House. With Union cavalry again in front of them and enemy infantry moving to surround them from the rear, Lee bowed to the inevitable and surrendered to Grant on April 9. The Civil War, to all intents and purposes, was over.

My great grandfather Michael Byrnes Sr was captured at the battle of Sayler’s Creek. He was a confederate marine from the CSS Virginia.