By Steven D. Lutz

It seemed like just another ordinary day at sea. Early on December 7, 1941, a U.S. Army-chartered cargo vessel, the 250-foot SS Cynthia Olson, under the command of a civilian skipper, Berthel Carlsen, was plying the Pacific waters about 1,200 miles northeast of Diamond Head, Oahu, Hawaii, and over 1,000 miles west of the Tacoma, Washington, port from which she had sailed on December 1.

On board the unarmed Cynthia Olson, formerly the Coquina and renamed for the daughter of the owner, Oliver J. Olson Company of San Francisco, California, were several tons of supplies destined for the U.S. Army in Hawaii. Thirty-three Merchant Marine crewmen and two soldiers were accompanying the cargo

Unknown to the crew of the Cynthia Olson, the Japanese submarine I-26, under Commander Minoru Yokota, was running alongside the slow, fat target, waiting for the moment to attack. The I-26 was about to strike the first blow of World War II against America.

“Tora, Tora, Tora”

Five days earlier, Yokota had received the coded message, Niitakayama nobore 1208 (“Climb Mount Niitaka, December 8”). The signal meant that war with the United States would commence on December 8, Japan time, or December 7 in Hawaii. Among the nine Japanese submarines assigned to patrol the waters between Hawaii and America’s West Coast, the I-26 had been at sea for a month. Its initial sea service took it to Alaska’s Aleutian Islands; it was then ordered south to look for American ships.

At dawn on December 7, 1941, Yokota and his 90 submariners went to battle stations and surfaced. A warning shot from I-26’s deck gun raced across the Cynthia Olson’s bow. While skipper Carlson attempted some evasive maneuvers, the Olson’s radio operator sent out a distress call, but the ship had nothing with which to fight back.

Now the 5.5-inch shells from the sub’s deck gun began to find their mark, and flying shards of steel sent the crew rushing for the lifeboats. The I-26’s gunners kept up the one-sided battle until 18 rounds had been expended and the badly damaged cargo ship appeared to be riding low in the water. She refused to sink, however, so Yokota submerged and fired a torpedo at her, but it missed. Resurfacing, Yokota ordered the deck gun to resume firing. Only after another 30 shots were fired did the Cynthia Olson go under.

During the shelling, a coded message was received aboard the I-26: “Tora, Tora, Tora,” indicating that the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor had commenced and everything seemed to be going well for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). As the Cynthia Olson slipped beneath the waves, the I-26 turned and sailed away, leaving the men on the transport ship and in the lifeboats to their fates; none survived.

Thus began Japan’s submarine war against the United States.

The B-1 Class Submarine

Truth be told, the Imperial Japanese Navy had been preparing for submarine warfare long before Pearl Harbor. In time they honed a design to do just that. It became their B-1 class submarine. The B-1 class was designated the “I” Series, and 20 of them would sail the Pacific Ocean during the war.

The typical B-1, with a crew of 95 men, was 356 feet long and 30 feet at the beam with a hull 17 feet high. Its standard weight was 2,200 tons, and it could carry 800 tons of diesel fuel that enabled it to cruise 14,000 miles at 16 knots (17.6 mph) per hour. Its top speeds surfaced were 23.5 knots (25.3 mph) and eight knots (8.8 mph), respectively. It carried 17 torpedoes and had a deadly 5.5-inch deck gun. To ward off encroaching enemy aircraft, it employed two 25mm machine guns. Its safest maximum depth was 330 feet.

What made the B-1s unique was that each submarine housed one Yokosuka E14Y1 scout plane (code named “Glen” by the Allies) inside a watertight, on-deck hangar forward of the conning tower. A double-track launch rail catapulted the plane to get it airborne. Its normal cruising speed was 85 mph, with a maximum speed of 150 mph. Although the plane’s primary role was scouting and it could do so with a 200-mile radius in a five-hour flight time, it could also carry a maximum bomb load of 340 pounds. The Glen’s second crew member, a gunner, sat facing rearward behind a single 7.7mm machine gun.

Angeles.

To fit a Glen into the onboard hangar, its wings, floats, and tail assembly were either removed or folded. With a crew of four it could be made air ready in less than 40 minutes. Upon returning, it landed next to the sub where a crane lifted it back on board. Crew members then disassembled it to fit it into the hangar.

Before the war, America’s military had no idea the Japanese had such capabilities. These weapons, the “I” subs and warplanes, were state of the art.

Japan’s antagonistic attitude against America rose between 1922 and 1930. Japan keenly felt snubbed by the Western Allies following their World War I victory. During the negotiations of naval limitations in Washington, D.C., in the 1920s, restrictions were placed on the naval power of the United States, Great Britain, and Japan in a ratio of 5:3:3. In other words, for every five warships America and England built, Japan could only produce three. The Japanese considered this a blow to national prestige and their expansionist aims.

From that point on a grudge match evolved between Japan and America, and the militarists in Japan began scheming for retribution as early as 1931. At that time Japan was considering stationing four mine-laying submarines off the West Coast should hostilities with the United States erupt. A major emphasis was placed on developing state-of-the-art submarines that could carry their own reconnaissance planes stored in on-deck hangars. (See WWII Quarterly, Winter 2012.)

Submarines Off San Francisco

Three days after the sinking of the Cynthia Olson, December 10, 1941, the I-26, along with other subs, was called back toward Pearl Harbor. It was imperative that the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier Lexington be located and removed from action, but a four-day search proved fruitless. A new role was then established for the submarines. Vice Admiral Mitsumi Shimizu, commander of Japanese submarine forces, directed Rear Admiral Tsutomu Sato in his flagship I-9 to park his nine submarines off San Francisco by December 17 and commence bombarding the city on Christmas Day. Each submarine was ordered to surface, then fire no fewer than 30 5.5-inch rounds into the city.

Beyond the Golden Gate Bridge the nine subs loitered undetected and waited for December 25. During the week before Christmas they cruised out of sight and resurfaced at night to recharge batteries as needed. On the 22nd an unexpected order was received postponing the attack until December 27. That order came directly from Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander in chief of the Combined Fleet.

Five days later, Sato had a message to share with headquarters. His subs were drastically short of fuel. In all probability the attack could still commence on the 27th, but the complication would come in returning to Japan. Literally speaking, some subs might run out of fuel. Yamamoto called off the attack for that—and for another reason.

During the 1920s, Yamamoto had studied at Harvard University. He observed America’s industrial capacity and realized that Japan could not hope to win a protracted war with the United States. Yamamoto was further hesitant to attack the U.S. civilian population, particularly during a holiday, and was concerned about U.S. retailiation sometime in the future.

Four and a half months later, Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle’s carrier-launched North American B-25 Mitchell bombers, seeking revenge for Pearl Harbor, struck Tokyo. Had Yamamoto known that Tokyo would be bombed, he may well have authorized the shelling of San Francisco.

Christmas Eve Attack on the Absaroka

At 10:30 am on Christmas Eve, one of the Japanese submarines nevertheless went into action near Los Angeles. The submarine I-19, captained by an officer named Nahara, was cruising off Point Fermin in the Catalina Channel when the 5,700-ton freighter Absaroka, which had sailed from Oregon with a load of lumber, was spotted heading south for Los Angeles harbor.

The I-19 launched a torpedo that struck the freighter at the No. 5 hold, causing extensive damage and blowing the cargo from the hold into the air. A crewman was killed by flying debris. The radio operator sent an SOS signal, but within minutes the Absaroka had settled to her main deck. As the crew abandoned ship, one of their two lifeboats capsized, but the surviving 33 men managed to escape in a single lifeboat.

Shortly after the SOS went out, American war planes arrived and dropped bombs near where the sub was last seen. Following the aircraft attack, the patrol yacht USS Amethyst (PYc-3), assigned to the Inshore Patrol, 11th Naval District, and patrolling the entrance to Los Angeles harbor, dropped 32 depth charges.

The Absaroka’s crew was picked up over an hour after the attack, and the freighter was later reboarded by the Coast Guard, towed into San Pedro harbor, and beached below Fort MacArthur.

Kozo’s Raid on the Ellwood Richfield Oil Refinery

After the attack on the Absaroka, coastal defenses were strengthened around Santa Monica Bay and Redondo Beach. In early 1942, soldiers from Fort MacArthur installed two 155mm cannon and machine guns at the end of the Redondo Pier. This battery, known as Tactical Battery 3, was one of several around Santa Monica Bay. There were similar batteries installed at Pacific Palisades, Playa del Rey, El Segundo/Hyperion, Manhattan Beach, and Rocky Point and Long Point (both Palos Verdes). California was getting ready for invasion.

American soil was finally attacked by a Japanese submarine on February 23, 1942.

The sub that launched the raid was Commander Nishino Kozo’s I-17, commissioned a year earlier at the Yokosuka Navy Yard. Prior to the war, Kozo had captained a Japanese merchant ship that made stops in California’s Santa Barbara area at the Ellwood Richfield Oil Company refinery and storage facility, so he was familiar with the territory.

Kozo had another reason for the attack on the Ellwood oil facility. Prior to the war, he paused there to refuel his ship. As was the custom at the facility, Nishino came ashore to be greeted by the president of Richfield Oil Company. His party crossed the sandy, pear cactus-covered beach. Nishino lost his footing and fell onto one of the thorny plants. He took a couple of prickly thorns in his posterior and suffered a great deal more embarrassment when nearby depot workers laughed.

In the week prior to the attack, numerous nervous residents reported sightings of unidentifiable submarines surfacing off shore, but none were taken seriously. Besides, little could be done about it. Defenses at the oil storage facility were scant, consisting only of two obsolescent World War I howitzers at different locations. The closest officer in charge of those units was Captain Bernard E. Hagen of A Battery, 143rd Field Artillery, 40th Division. Furthermore, the Coast Guard patrol boat that was normally assigned to that area was off duty by the 23rd. At 7 pm that night, President Franklin D. Roosevelt commenced his radio fireside chat. Those in the Santa Barbara/Goleta area settled in to listen.

From the I-17’s vantage point on the surface, traffic along Pacific Coast Highway 101 was easily visible through binoculars. Oil derricks stood out just as plainly. There seemed to be no noticeable defenses or state of alert. Kozo’s plan was to fire at least 20 shells into the facility before any coordinated reaction came from defensive positions, as he expected would happen. At 7:07 pm the I-17 fired the first of 15 or 16 rounds into the depot from about a mile off shore. Most of the 5.5-inch shells fell harmlessly into the water, overshot the target, or landed as duds.

At 7:35, assuming that the Americans would be hot on his trail, Kozo fired his last round and beat a hasty retreat into the dark. He could have made a leisurely escape as nobody fired at his boat or came after him.

The results of the attack were minimal, producing only a slightly damaged derrick and a shot-up pier amounting to a few hundred dollars. But the panic caused by Kozo’s less-than-spectacular raid was incalculable. Mainland America had been attacked! People did not know what to do. Residents of Ellwood jumped into their cars and drove madly inland, trying to escape the attack and worried that an invasion would follow. The local phone lines were so tied up that no military calls could get through.

Following the shelling, Captain Hagen and a master sergeant went to the refinery and were defusing dud rounds when one detonated and Hagen received a shrapnel wound. He became America’s only assigned service member to receive the Purple Heart for a wound received from hostile action on American soil.

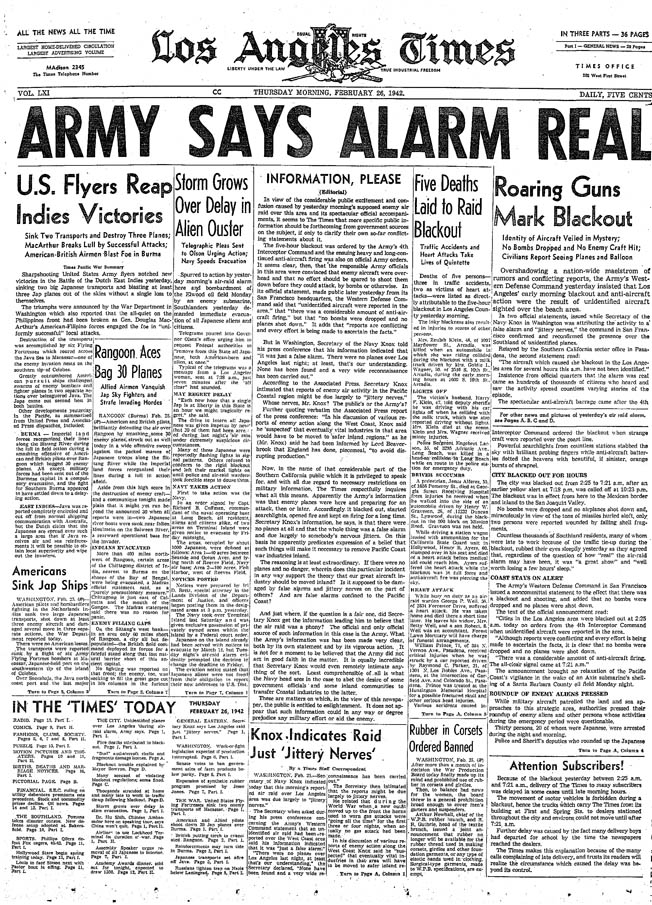

“L.A. AREA RAIDED”

The San Pedro Naval Operations Base sent three planes and two destroyers to scour the area. The planes evidently saw something and dropped flares and depth charges to keep the enemy submarine submerged until the destroyers arrived. At 4:51 the next morning, the U.S. Navy reported that the USS Amethyst had made contact with a submarine three miles southwest of Point Vincente and was dropping depth charges. The Amethyst also reported that she had evaded a torpedo.

War jitters were rampant in the wake of Pearl Harbor, the submarine attacks on coastal shipping, and I-17’s shelling of the Ellwood oil facility, just 80 miles from Los Angeles. Many saw these events as precursors of a greater attack, and tensions rose rapidly along the coast, a prelude for the “nonattack” on the West Coast, the so-called Battle of Los Angeles.

The forced evacuation and relocation of ethnic Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians from the coastal states and western Canada was just a few days old when, late on February 24, rumors of an impending attack on Los Angeles began to circulate. Around midnight, a report was sent out to antiaircraft batteries on the heights overlooking the L.A. area that enemy planes had been spotted, and the Battle of Los Angeles was on. One of the batteries opened fire on the unseen airplanes, and searchlights scanned the sky. The panic soon spread, and other gunners opened up.

Air-raid wardens dashed about, ordering people to extinguish lights and take cover. A number of auto accidents occurred as drivers drove through darkened streets with their headlights off, and several people suffered heart attacks, including one that was fatal. Some civilians rushed for shelters, while others went outside to see what the noise was all about. Some thought they saw the planes, while others thought they saw parachutes and bombs falling. Spent antiaircraft shells (over 1,400 were fired) and shrapnel rained down on homes and cars, with Santa Monica and Long Beach taking the brunt of the fallout.

There were also rumors that an enemy plane had been shot down and crashed at 185th Street and Vermont Avenue, and that other sections of the city were on fire.

The “battle” lasted over two hours before common sense prevailed and the guns fell silent. The next morning’s Los Angeles Times headline declared in bold type, “L.A. AREA RAIDED.” Like the rest of the populace, newspaper editors had succumbed to the rumors. A 1983 Air Force report attributed the panic to the sighting of a runaway weather balloon.

The fact that the city had not been bombed quickly became apparent, and there was plenty of chagrin and embarrassment. The realistic, unplanned air-raid drill was actually beneficial for Los Angelenos, however, because they gained experience in case the real thing happened. The Japanese did have plans to use giant seaplanes to bomb the city.

Two Attacks by I-25

Of the nine I-boats off America’s northwest coast, the busiest may have been Commander Meiji Tagami’s I-25, which made two direct attacks on American soil. After putting out to sea on October 15, 1941, the I-25, like several of the other I-boats prowling the American West Coast, was a brand-new vessel. Arriving on station one week after Pearl Harbor, Tagami, like some of his fellow I-boat commanders, proved to have sloppy work habits.

The I-boats had one crippling restriction when attacking merchant vessels. They were allowed to fire only one torpedo per merchant ship. Everything else had to be done via the deck gun. On December 14, the I-25 had sent 10 rounds toward the Union Oil tanker SS L.P. St. Clair, but all 10 missed. The tanker escaped into Oregon’s Columbia River estuary, which separates southern Washington from northern Oregon.

Twelve days later, Tagami and I-25 crossed paths with the 8,684-ton tanker SS Connecticut. This time Tagami exercised his single-torpedo option. He hit the target and set it afire, but it ran aground at the estuary. Afterward, Tagami departed for several months to attack military shipping in the Marshall Islands. He would return.

Near where the Columbia empties into the Pacific Ocean stands Fort Stevens, constructed on the Oregon side of the river during the Civil War. By 1941, its 10-inch coastal defense guns were near-antiques left over from World War I. The eight original guns were made in 1900 and installed at the site in 1904, but six of them had been removed, as local residents complained of their excessively noisy concussions during firing practice. The two remaining pieces, capable of firing 617-pound shells up to nine miles, were mounted at Battery Russell on carriages that retracted out of view. The fort was manned by the Oregon Army National Guard’s 249th Coastal Artillery Battalion, led by Lt. Col. Lifton M. Irwin.

Three months after Doolittle’s April 1942 bombing raid on Tokyo, Tagami and I-25 approached Fort Stevens. Believing that he had a worthwhile target before him (Fort Stevens was wrongly thought to be the entrance to American submarine pens), Tagami submerged and followed a collection of fishing boats closer to shore. Just before midnight on June 21, 1942, the I-25 fired 17 5.5-inch rounds in the direction of Fort Stevens. Tagami expected immediate return fire, so he ordered his gun crew to fire as quickly as possible without bothering to aim properly.

Those on shore would testify that only half the shells hit the ground. The rest were either duds or landed in the water. The most property damage done was to the post’s baseball field and a power line. One soldier incurred an injury running to his post.

Having quickly fired his rounds, Tagami made a hasty escape, but not a single shot was returned his way. Captain Jack Wood’s Battery Russell failed to reply. Gun crews totally miscalculated I-25’s position, believing it was out of range. The post commander ordered Wood to hold his fire so as not to reveal the fort’s exact gun positions.

Tagami later asserted that had he known of the fort’s insignificance he never would have fired on it. By mid-July 1942, the I-25 was back at its naval base of Yokosuka.

Nobuo Fujita: Determined Aerial Raider

Whatever Japanese intentions were for America’s West Coast, they never fully developed. But if there was a shining star in their abortive show, it would be Warrant Flying Officer Nobuo Fujita.

Fujita was born in 1911. Twenty-one years later he was drafted into the Navy and he became a pilot in 1933. Fujita was aboard the I-25 during a deployment in the Aelutian Islands. In the spring of 1942, he had flown above Kodiak Island at 9,000 feet and observed that the American response to an unidentifed plane was apparent indifference.

Fujita suggested an air raid against the United States utilizing Glen reconaissance planes launched from surfaced I-boats. The proposal was later endorsed by Prince Nobuhito Takamatsu, younger brother of Emperor Hirohito.

When a Japanese official who had been previously assigned to the consulate in Seattle, Washington, mentioned that late summer was quite dry in the Pacific Northwest, it was decided to launch such an attack, dropping incendiary bombs to ignite major forest fires and threaten population centers.

Fujita had also noted that the Panama Canal could be similarly targeted. The I-25, under Tagami, left Yokosuka on August 15, 1942, and headed back toward America’s West Coast with pilot Fujita and six 170-pound incendiary bombs aboard.

Each incendiary contained over 500 igniting elements that would disperse across a 100-yard blast area. Fujita’s aircraft would deliver two such bombs on successive flights.

Arriving off the Oregon coast during the first week of September, the I-25 whiled away the days waiting for a strong storm to blow over. Unusually heavy rain pelted the area, but in the predawn hours of September 9, 1942, conditions had moderated and Fujita and his bombardier, Petty Officer Shoji Okuda, were propelled off the sub. Flying 50 miles eastward, Fujita saw the lighthouse at Cape Blanco, and it became their beacon.

The first bomb was dropped 50 miles inland. Six miles farther, the second was released. In a flash both ignited. The two fliers fully believed they had succeeded and enthusiastically shared the news with Tagami. However, although both bombs exploded, the foliage was too damp from rain and lingering mist for a raging fire to develop. Fire warden Howard Gardner and one volunteer, Keith Johnson, easily controlled what smoldered.

A second raid went ahead on September 29 in the same general locale. Fujita reasoned that no one would expect a repeat incident. Flying 90 minutes inland, he let two bombs go. They plummeted onto a site called Grassy Knob near Port Orford, Oregon, but even less came of these as the wet foliage refused to catch fire.

Finding his way back to I-25 was a challenge for Fujita because of low cloud cover. He was able to find the submarine by following a trail of oil on the ocean’s surface. The I-25 had been previously attacked by air, and no one was aware of an oil leak until it was seen from above.

Unfavorable weather and heavy seas precluded a third attack.

Project Fugo

Later in the war, the Japanese resorted to using long-range, high-altitude balloons to cross the Pacific in hopes of starting forest fires. They were as ineffective as the bombers. However, in one unfortunate incident, several civilians were killed when a bomb exploded near their picnic site.

One question remains: Why did the Japanese choose the isolated region of Brookings, Oregon, to drop their bomb? Nothing of significance was there. even massive forest fires would not have impaired the American war effort.

Recalling the I-Boats

By the end of 1942 most of the I-boats off the West Coast had been recalled for operations elsewhere in the Pacific.

The Japanese did contemplate another air raid plan, this one involving the Kawanishi H8K “Emily” flying boat. The Emily had four engines and floats, making it a bomber-reconnaissance seaplane. Its wingspan extended 124 feet, and its fuselage was 92 feet long. It had a maximum air speed of 290 mph, a cruising range of 4,400 miles, and a bomb load of 5,000 pounds, with an armament of four 7.7mm machine guns and six 20mm cannons. In time, a dual 20mm cannon replaced the machine guns. By war’s end, 131 Emilys had been built but failed to realize their potential.

Lieutenant Commander Tsuneo Hitsuji, himself a pilot, proposed flying six updated Emilys to just off the California coast. There a flotilla of I-boats would meet them for refueling. The Emilys would then bomb Los Angeles. After hitting their targets, the planes would fly as far west as possible, seeking Japanese-held territory for landing.

Hitsuji dreamed even further. A fleet of 30 H8K2s might set down in Mexico’s Baja California waterway. There Japanese I-boats and German U-boats could surface to refuel and load them with bombs. Their new targets would be the Texas oilfields and beyond. With a 4,400-mile range, the Emily could fly any direction to hit the interior of America. Alas for the Japanese, as with other grandiose schemes, time ran out.

The Japanese threat to the U.S. West Coast never became substantial. The Imperial Navy claimed to have sunk five freighters off the West Coast for a total of 30,370 tons. Five others were damaged but salvageable. Captains of the I-boats grossly exaggerated America’s military response to their attacks.

The few responses made by the U.S. military were often as haphazard as the I-boat attacks. In the end, Japan never had the time, opportunity, or resources to launch a major offensive effort against the continental United States.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments