By Flint Whitlock

The night of June 5/6, 1944, was pretty much like every other night since the Germans had occupied Normandy and the Cotentin Peninsula in the summer of 1940: dark, quiet, chilly, and mostly boring.

While there had been innumerable overflights by Allied aircraft (probably taking reconnaissance photos) and the occasional aerial bombing, Normandy was still considered good duty for anyone who had had his fill of war on the Eastern Front and was recovering from wounds psychological and physical.

Here in Normandy there was plenty to eat and drink (especially Calvados, the strong brandy made from apples), scenery that hadn’t been mostly destroyed by heavy fighting, and French people who seemed to, if not exactly warmly welcome, at least be resigned to and tolerate the presence of foreign soldiers on their soil.

When not on actual watch, looking for the first signs of an invasion that might or might not come to this location, the soldiers in Normandy had busied themselves by following Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s orders to so strongly fortify the coast that the Allied invaders would not stand a chance, that they would, as Rommel had put it, be driven back into the sea.

This night, with the peninsula cloaked in darkness, and the farmers and villagers fast asleep beneath the cloud-obscured moon and the German soldiers—who were on watch in their observation bunkers straining with the help of strong French coffee to keep their eyelids open and scan the black horizon or sound asleep in their barracks or making love to their French mistresses—had no idea what was about to hit them.

A glance at a map of northwest France reveals a basic truth: there are no large cities in the arc between Cherbourg and Caen; only Carentan, Montebourg, Bayeux, and Valognes can be regarded as sizable. A spiderweb of roads connect one town and village and hamlet to another. One town at the center of a web of roads is Sainte-Mère-Église. But the roads—mostly narrow farm roads suitable for bringing produce to market or for driving herds of slow-moving cows from the barn to the fields and back again—also made it hard to move large formations of military vehicles and large numbers of troops.

For centuries—ever since the Vikings or Normans first set foot here, giving the region its name of Normandie—the area has been pastoral and bucolic, with time measured by seasons rather than by the clock. The sturdy homes, shops, and churches are built solidly of stone—a whitish-grayish-yellowish limestone native to the region, capable of fending off the strong winds that blow in fiercely from the North Atlantic and sometimes rattle the shutters and windowpanes. Although treated to the same warm currents that can give southern England a semi-tropical feel (there are, after all, palm trees growing along the English Channel), the winds can sometimes be bitter, and the cold can penetrate through multiple layers of fabric like a gunshot.

The people, too, like their buildings, are a sturdy lot. Hard-working like any agrarian populace, the dour Normans typically rise at (or before dawn), put in a full day’s worth of physical work, eat a hearty dinner topped off with a glass or two of Calvados, and retire at sunset.

The stolid citizens of Normandy were not happy, of course, when, in June 1940, the gray-uniformed Germans marched in and took over, but they accepted their fate the way they accepted most everything that came their way. For the most part, they did not go out of their way to welcome the occupiers, nor did they collaborate with them. They merely tolerated them and went about their usual business of growing the apples that went into the making of Calvados, pulling fish from the Channel, and pasturing their cows, extracting the milk to make into cheese.

It was Sainte-Mère-Église, roughly halfway between Montebourg and Carantan, that had caught the eye of American military planners as early as 1942. Control Sainte-Mère-Église and you control the Cotentin, the planners saw. No fewer than five roads pass through it, plus it was only seven miles from the westernmost amphibious landing beach known as Utah. Drop an airborne division or two, along with their glider-infantry regiments, into the area and you stood a good chance of preventing German reinforcements from Cherbourg in the north and Brittany in the west from slamming into the troops coming ashore at Utah. The western end of the 60-mile-long beachhead that ran from La Madeleine to Ouistreham would thus be secure and the seaborne troops could move inland after overcoming local German opposition. Yes, Sainte-Mère-Église would definitely have to be taken in the early hours of D-Day.

In the days before D-Day, Alexandre Renaud was a man with a dilemma. Besides his full-time job as the local pharmacist, the World War I veteran was also the mayor of Sainte-Mère-Église and, as such, he was expected by the occupiers to cooperate with them—and by his constituents to resist. Whenever the Germans gave him an order to do something, such as provide tools, transportation, and laborers to assist in the building of some defensive work, and he could find no one willing to perform the work, punishments would follow.

In May 1944 the Germans were demanding all sorts of things. It was obvious that the local Germans were expecting an invasion and that Sainte-Mère-Église would likely be caught up in it. The roads through the town were filled with trucks towing artillery pieces and carrying troops in all directions. In the fields cordoned off by hedgerows, holes were being dug and large poles were being planted—Rommelspargel (Rommel’s Asparagus) some wag called them—designed to discourage glider landings. Trenches were being dug, and anti-aircraft guns emplaced.

When Renaud spoke clandestinely with townspeople, everyone seemed to have an opinion: the Allies—if and when they attack—will cross at the Pas de Calais, Cherbourg, Le Havre, Dieppe, Boulogne, Dunquerque. Brittany will be the target. No, it will be the Cotentin. Ridiculous—the Allies will feint at Normandy but land on the Belgian coast. Few thought that Sainte-Mère-Église was in any real danger unless Allied bombers decided to target the anti-aircraft batteries that were being installed around the town. After all, air attacks had struck at the bridges at Beuzeville la Bastille and Les Moitiers en Bauptois. Someone else pointed out that leaflets were recently dropped over the area hinting at paratroop landings and showing illustrations of Allied tanks and jeeps and what British and American paratrooper uniforms looked like, and giving instructions on what to do in the event of an invasion. The Allies are probably dropping them all over France, someone else pointed out, just to keep the Germans guessing.

Renaud noted that the digging of trenches around Sainte-Mère-Église was almost completed, but that the Germans didn’t seem to be in any rush. “With the means of punishment at its disposal,” he said, “[the German command] could have made the work go five times as fast, and could have demanded that it should be done by June 1st.”

Throughout May, the presence of German troops increased. Renaud said, “We have seen encamped in our fields infantry, artillerymen, Aryan Germans, and also Georgians and Mongols with Asiatic features … commanded by German officers. In the latter part of May, the artillery units quarter in Gambosville [less than a mile south of Sainte-Mère -Eglise]. The officers come to see me at the Town Hall. They need spades, picks and saws immediately. The town is to be secured, and the work has to be finished in five days.

“I reply that there are no more spades or saws in the neighborhood and that they will have to canvass all the houses in order to find a few tools. They phone the Feldcommandantur at Saint Lô to get instructions about what punitive measures to take. He gives an evasive answer. Discouraged, they finally go to a hardware store where, after threatening to loot everything, they manage to obtain a few tools. Guns are then installed at all the town approaches; on the Carentan road, on the La Fière road, before Capdelaine, on the Ravenoville road.

“Then, suddenly, three days after their installation, the guns are taken away, and I am asked to provide transport immediately to haul ammunition and food to Saint Côme-du-Mont . . . . Sainte-Mère-Église is once again alone with its anti-aircraft unit.”

The invasion—Operation Overlord, with the airborne phase known as Neptune—had been delayed for a day because of a fierce storm that had swept over England, the English Channel, and the Normandy coast, but now it was back on. At RAF airfields with such quaint, typically English names as Upottery, Cottesmore, Down Ampney, Tarrant Rushton, Greenham Common, Barkston Heath, Brize Norton, and others, superbly trained British, American, and Canadian paratroopers and glider infantrymen waited for the orders to go.

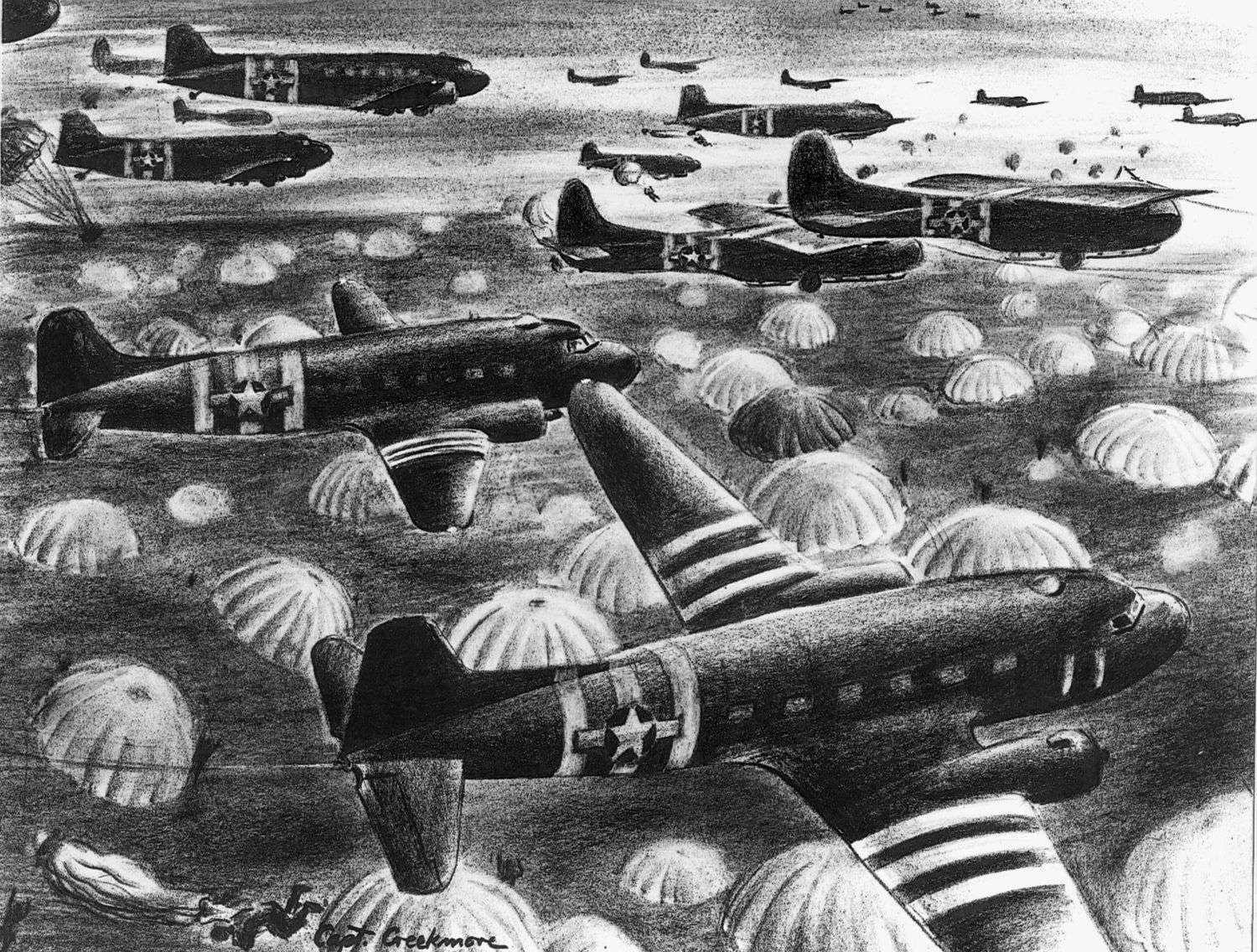

The U.S. 82nd and 101st and British 6th Airborne Divisions had been training for months in anticipation of just this moment. Despite some SHAEF staff officers’ worries that the American airborne and glider operations would meet with disaster, everything that could have been done to ensure success was done. The maps, aerial photos, and sand table models of each unit’s objectives had been carefully studied and memorized. Each plane had its precise schedule as to when it was to take off. All the necessary equipment had been gathered and issued. Knives and bayonets had been sharpened, faces blackened with burnt cork, last letters home written, last prayers said.

The advance U.S. assault wave that would strike Normandy before the seaborne troops arrived numbered about 17,000 men being carried by 822 C-47 transport planes. They were the dice that American Generals Eisenhower and Bradley were willing to throw. Although the overwhelming majority of the sky soldiers had never been in combat before, and had only an inkling of what to expect once they reached France and the bullets began to fly, they were supremely confident of victory.

Sergeant Spencer Wurst, an 82nd Airborne trooper, spoke for them all when he said, “It may seem naïve now, but at no time did we ever dream that we would not be successful in Normandy. We never even mentioned the possibility of defeat. The commanders may have agreed among themselves that if the beaches were not held successfully, everyone who could get out would head for Sainte-Mère-Église. But down at my level, absolutely nothing was said about withdrawal or evacuation.”

“That evening [June 5] we got the word that we were going,” said Henry “Duke” Boswell, G Company, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne. “They took us out to the planes in city buses; they didn’t have enough trucks. It was hard to get in the buses with all our equipment. We got to the plane and Lt. Col. [Ed] Krause, 3rd Battalion C.O., came around and talked to us, and every other word he had to say was a curse word; I guess he was a good leader, but I sure didn’t like that part of his personality.”

Boswell also remembered that Krause held up an American flag and said, ‘This was the flag we raised over Naples when we took Naples, and when you meet me in Sainte-Mère-Église, we’re going to raise this flag there.’ We loaded up [on the plane] and we were nervous. Some of the guys tried to joke, but most of the guys were quiet. Some of them had been in combat before and some hadn’t; we had had a lot of replacements. Everybody was just kind of thinking their own thoughts.”

On the flightlines of a dozen British airfields, the C-47s began to roll, then took off into the dark sky and headed for France. The invasion was on, and no force of man or nature could turn it back now.

Because of the German-imposed curfew, the town of Sainte-Mère-Église, like all the towns in Normandy, was dark and shuttered tightly on the night of June 5, 1944. Mayor Renaud was awakened shortly after midnight by the distant thumping of anti-aircraft batteries. As a precaution, he herded his wife and children into the family’s makeshift bomb shelter when there came a pounding on his door. Renaud opened it to find the town’s fire chief standing there in his shiny brass helmet, anxiously informing him that the two-story home belonging to the Hairon family, just off the southeast corner of the town square, was ablaze. The chief asked the mayor if he could get the commandant to lift the curfew. Renaud said he would try.

He hurried to German headquarters at the town hall, explained the situation to the duty sergeant who, without waking the commandant, gave Renaud permission to call out the volunteer fire department and citizen bucket brigade to help extinguish the fire. German guards were also called out to stand watch over the volunteers and make sure no acts of sabotage were committed.

Renaud then dashed to the parish house and asked Father Louis Roulland to have the sexton toll the bell as a means of alerting the citizenry. Soon more than a hundred men and women, some still in their nightclothes, had assembled outside the church to form a line of buckets from the pump at one end of the Place de l’Église to the firemen at the scene of the fire some 50 yards away. Some 30 well-armed German soldiers stood watch over them.

While the British 6th Airborne Division was crossing the Channel toward its objectives at two bridges over the Orne River and Canal and the casemated guns at Merville on the far eastern flank of the 60-mile-long invasion area, the paratroopers of Matthew Ridgway’s 82nd Airborne Division—“Mission Boston”—were following the C-47s that were carrying Maxwell Taylor’s 101st Airborne troopers.

The invasion route took the airborne armada to the western side of England, then south toward the Channel Islands, finally east across the Cotentin Peninsula. The C-47s were in formation and traveling at 130 mph; as they approached the drop zones, the pilots would reduce speed to about 110 mph or less.

In a C-47 that was carrying 18 paratroopers from Company H, 508th PIR, 82nd Airborne, Lieutenant Victor Grabbe was leading his men in song, even though the tune and lyrics were swallowed up by the sound of the engines.

One of Grabbe’s men, Lew Milkovics, recalled, “All was quiet for a time while we were flying over the Channel. Most of us, like myself, I am sure had our thoughts on our loved ones and, no doubt, were feeling sorry for ourselves as we knew what would soon be happening. We wondered how many of us would survive. Lieutenant Grabbe sensed the tension and he loudly shouted, ‘Hey, fellows, how about some songs?’

“That broke the silence. Someone started with ‘Let Me Call You Sweetheart,’ then ‘Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree with Anyone Else But Me,’ then ‘Deep in the Heart of Texas.’ And so it went as we sang many more oldies for the next 10 or so minutes. It was great, as it relaxed us, and took our minds off ourselves and the coming danger.”

Milkovics said, “I sat there thinking, ‘Boy, that Grabbe—he is one smart cookie.’ Under our kind of pressure, I doubt if any other stick leader thought to do this. I will never forget the intelligence and smart thinking of our lieutenant.” Unfortunately, Grabbe would die of wounds suffered in the upcoming battle.

Sergeant Otis Sampson, E/505/82nd, remembered his flight being quiet, no singing, “each man with his own thoughts as the plane winged its way to our rendezvous; each second drew us closer. As we crossed the coast of Normandy we stood up and hooked up. I saw no guns firing below. Everything was going good, too good for my liking; it seemed we were going into a trap. Being near the open door, I could see the moon-drenched countryside below, with no sign of life. I stood with perfect control of my mind and body as the plane went into a dive…. We leveled off and then went into another dive. By this time we were well inland; the plane slowed down. It looked so peaceful below. I never expected it to be that way.”

In the lead ship was the 82nd’s assistant division commander Jumpin’ Jim Gavin; he would be jumping with the 508th. He wrote in his memoirs, “We began to receive small-arms fire from the ground. It seemed harmless enough; it sounded like pebbles landing on a tin roof. I had experienced it before [over Sicily] and knew what it was.”

Shortly after the planes entered the airspace over the Cotentin, they flew into a bank of thick clouds. Sergeant Elmer Wisherd, a flight engineer in a C-47 carrying elements of the 101st, recalled the heart-stopping moments when his formation hit the clouds: “I can’t figure out how we went through those clouds without collisions or damage to the planes. Then we came out and started getting AA fire. I could see the other planes around us taking ground fire. We went back up through the clouds; it was quite a layer of clouds. And we came out in formation! How we did it I have no idea. Our pilots were the best, all instrument-rated pilots. There was no talking between planes whatsoever—complete radio silence. But I’ll tell you, it was ‘pucker’ when you’re going through clouds and you can’t see the airplanes around you and all at once you pop out on top and here you are, still in formation. Then we dropped to 800 feet. It was clear over the drop zone.”

At the controls of a C-47 loaded with 82nd Airborne troopers was 1st Lt. Bill Thompson. Despite the months of training, he recalled that many of the other pilots panicked when they flew into the clouds and when the ground fire began to reach up for them. Many broke formation, swerving wildly to avoid the ordnance, suddenly accelerating, or violently going into steep dives or sudden climbs.

“I could see the tracers in front of us,” Thompson said. “They were leading us too much since they probably were not used to firing at slow-flying aircraft. We did not get hit so finally I let down some more and broke out of the clouds. I could see the water on the other side…. My right wingman saw the water and I guess he got excited and started dropping [his paratroopers] before I signaled him to.”

Lieutenant Edward V. Ott, Headquarters, 2/508/82nd, said that he felt the drop “was doomed to be a disaster when the C-47 pilot began to take evasive action to avoid the heavy flak. He gave us the green light when the plane was in a climbing attitude as the engines roared at top speed. When I jumped, the prop blast was so severe that it tore off my pack and equipment so that when I hit the ground, the only weapon I had was my jump knife. I didn’t see any other member of my stick.”

Sergeant Ed Barnes, a communications section leader in 3/507/82nd, had dozed off during the hour-long flight but was awakened as the aircraft closed in on France. “We were given the signal to stand up and hook up and check one another’s equipment. We were all standing there poised and looking at the red light, waiting for it to turn green. As we peered out the door, we could see the flak and tracer bullets coming up out of the darkness. Then the light turned green and we started to pile out the door.”

As the jump master in his plane, Lieutenant J. Phil Richardson, H/508/82nd, recalled, “When we arrived at the drop zone in France, I looked down at the DZ and saw it was covered with tracers. I felt that we should not land in that area and I told the pilot not to slow down but to keep going, which he did. Soon, the English Channel became visible on the other side of the peninsula. We had an order that no airborne troops could return to England [by plane] once they had left. The area that I looked at then was clear of tracers and we did the jump there; this was near the small city of Bayeux.” But Bayeux was over 30 miles from H Company’s drop zone.

James Eads, another 82nd paratrooper, remembered vividly that his C-47 was receiving heavy AA fire on the run in. “We had been hit at the worst time by flak and machine-gun fire. We were off target. The green light came on and the troopers started out of the plane. The fifteenth man had equipment trouble. After some delay trying to fix his rig, I—being the 16th and last man to go out—bailed out on a dead run.”

Glen C. Drake, H/508/82nd, said, “I knew there was no one more anxious to get out of the plane than I. After hooking my static line to the steel cable that ran the length of the plane, I had to hang on to the cable and the side of the plane to stay on my feet. I was next to last of our stick, and I was wondering if I would get out.”

At last the green light came on and the line of heavily laden men began moving toward the door and disappearing into the night. “It seemed to take forever,” Drake said. “All the way back to the door we had to struggle to stay on our feet and I was thinking, ‘God damn it, let’s go, let’s go, let’s get the hell out of this damn plane before it goes down!’

“When I finally went out the door, I knew right away I had jumped from the frying pan into the fire! It was a night jump, but the hundreds of white phosphorous flares floating on small parachutes turned the night into day. What a field day those Krauts had—like shooting fish in a barrel!”

Sergeant Spencer Wurst, F/505/82nd, wasn’t happy about the haphazard nature of the drop. The discipline acquired over many months of training with the C-47 crews seemed to have evaporated in the heat of the moment, as pilot after pilot broke formation in an effort to avoid the ground fire. Hopelessly lost, and under orders not to bring any paratroopers back to England with them, some pilots simply flipped the switch that turned on the green “jump” light—whether or not they were over their designated DZ.

Wurst said, “As it turned out, 2nd Battalion, 505, had the best drop of all six regiments in the American airborne effort. We knew exactly where we were, we knew what we had to do, and we proceeded to do just that.”

In his C-47, Dwayne Burns, F/508/82nd, was becoming more and more anxious as the moment to jump grew nearer. The red warning light by the door suddenly came on, meaning that they were just minutes away from being given the “go” signal. The jump master in Burns’s plane “was hanging out the door, trying to see how far we were from land, when our airship entered a cloud cover and the pilots started to spread out. Most pulled up and tried going over the top. It was going to be bad for jumpers because we would be widely dispersed at landing, but the aircrew needed to avoid possible collisions. No one wanted to be taken out of action that way.

“It seems we stood in position for a long time before our flight began picking up flak; it was light at the beginning. At least I knew we were finally over the coastline. Then our waiting for the green light really started. The flak grew quickly and became really heavy while we tried to wait it out. The ship was getting pinged from all sides. The noise became awesome, an indeterminate mix of twin engines, flak hitting the wings and fuselage, and men yelling, ‘Let’s go!’ But still the green light did not come on.”

To Burns the aircraft “was bouncing like some wild bronco. A ticking sound danced across the bottom side of the plane as machine-gun rounds found us. It became hard to stand up while the pilots tried to maneuver and troopers lost their footing and fell down. They fought to get back up. Other jumpers had to help them but they could hardly remain standing themselves. Some were getting sick, I know, because the stench of vomit drifted my way from somewhere else. It was one hell of a ride. With all the training we’d had, there was still nothing that could have prepared a soldier for this event. I wondered if anyone of us would get out of the plane alive.”

The fire at the Hairon house was not anywhere close to being contained. And then they heard it, the citizens and the soldiers. Above the church bells and the noise of the fire and the people fighting it came the sound of aircraft, at first far off to the west but quickly growing closer and louder until it was a wall of thunder beating the air directly overhead. People looked up and out of the blackness there came human forms floating down beneath mottled green parachutes! They were American paratroopers, and they had come to liberate a continent.

All across Normandy in the early hours of D-Day, chaos reigned. Small groups and individual parachutists jumped into German positions and fought pitched battles with the enemy in the dark. Some troops landed in trees and dangled helplessly until they could either cut themselves down with their combat knives or were shot to death by the Germans. Others drowned in flooded fields, pulled underwater by their heavy equipment. Flaming transport planes crashed or exploded in midair. Farmhouses became fortresses, bridges barriers, and roadways killing zones.

The enemy had no idea of the scope of the airborne assault and fought back furiously, aware that their—and Germany’s—very existence depended on defeating the Allied paratroopers who seemed to be behind every tree, building, and hedgerow. In some cases, Soviet POWs, who had been impressed into German service, fought as fiercely as their German overseers but, given the opportunity, were more likely than not to surrender at the first opportunity. German commanders sent frantic messages back to higher headquarters where the captains and majors and colonels had no better idea interpreting what was transpiring than did the average Ländser in his foxhole.

Almost nowhere was the scene more chaotic than at Sainte-Mère-Église.

Spencer Wurst, F/505/82nd, was one of those dropping over the town. “The first thing I remember seeing as I descended was a large spire in a bunch of buildings that later proved to be Sainte-Mère-Église,” he said. “To my surprise, there were fires in the town. Almost immediately after—these things happen in microseconds—I started receiving very heavy light flak and machine-gun fire from the ground. This was absolutely terrifying. The tracers looked as if they were going to take the top of my head off, but they were actually coming up at an angle. Many rounds tore through my chute only a few feet above my body.

“The third thing I remember is the explosions on the ground, making me fear that the Germans had already zeroed in on our DZ. I later found out that these explosions resulted from our mine bundles. Either the speed of the plane pulled the chutes off, or the bundles dropped faster than expected, and the impact bent the safety clips on the fuses, causing them to explode.”

Another paratrooper, Pfc. Ernest Blanchard, was floating down over the town when a buddy next to him, loaded with a mine or demolitions, exploded and completely disintegrated right in front of him.

Duke Boswell, G/505/82nd, recalled, “When we jumped, we floated over the edge of the town. There was fire coming up. We could see the tracers from the machine guns. And you know for every tracer round you can see there’s about ten bullets in between. When they went by you, they’d pop and made you kind of jump. It’s funny—you jump with 10,000 troops and you hit the ground and you’re all alone. That’s a hell of a thing. For a moment or so, you’re right there by yourself, period. We actually hit our designated target, right outside Sainte-Mère-Église. I think that all of the other units, including the pathfinders that went in ahead of us, missed their targets. I landed within a half a mile of Sainte-Mère-Église, or closer.”

L ieutenant Vincent Wolf, a platoon commander in F/505/82nd, also had indelible memories of the drop. “The 2nd Battalion did not land in any of the flooded areas; that was mostly the 1st and 3rd Battalions, so we were lucky. After we landed, we took fire immediately from the Germans; thank God I had my Thompson sub-machine gun.”

Misdropped men from the 101st were also drifting over Sainte-Mère-Église. The jump master of his stick, Lieutenant Charles Santarsiero, 506/101, remembered looking out his C-47’s doorway as the plane neared the town. “I could see fires burning and Krauts running about. There seemed to be total confusion on the ground. All hell had broken loose. Flak and small-arms fire was coming up and those poor guys were caught right in the middle of it.”

Earl McClung, E/506/101st, was jumping with a leg bag full of machine-gun and mortar rounds that weighed more than 60 pounds. “I couldn’t lift it,” he said. When he jumped, he noticed that he was coming down above a town where a major fire was burning; it was Sainte-Mère-Église, and he was many miles from his intended DZ.

“I landed on the roof of a small Catholic shrine about a block and a half west of the church. I hit that roof and bounced off. It was pretty hectic for the first few seconds. Two Germans were running toward me. I guess they saw me coming down, but they were shooting at my chute that was on this little roof. I jumped with my M-1 assembled and in my hands. It was no contest—they were only a few feet away and I took care of those guys. At least I think I did; I didn’t wait around long enough to make sure. I went on by them and headed out of town. I ran through the graveyard and … joined up with the 505th of the 82nd for about the next nine days. I finally rejoined my unit at Carentan.”

Most of the parachutists landed safely in the dark fields around Sainte-Mère-Église, but some of them—primarily from F Company, 505th—were coming down in the very center of the town, where the light from the burning Hairon house made it easy for the Germans to spot them. Breaking out of their momentary bewilderment, the German soldiers suddenly unshouldered their Mausers and Schmeisers and began firing up at the descending forms. The paratroops hit the ground or landed in trees or snagged their chutes on utility poles, killed in their harnesses even before they could reach their Thompson sub-machine guns or remove their disassembled rifles from their carrying cases and put them together. It was an unmitigated slaughter.

The civilian bucket brigade scattered as the lead flew indiscriminately and a full-scale battle for the town square erupted. But neither the French nor the Germans immediately realized that the parachutists were Americans; most everyone thought they were British. As David Howarth noted in Dawn of D-Day, “The people of Sainte-Mère-Église, through all their years of listening to the BBC, had never dreamed that their liberators, in the end, would be Americans.” It was only after the American flags sewn onto the sleeves of the dead paratroopers’ jump jackets were seen that the truth became known.

One paratrooper was caught in a tree near the church and was machine-gunned to death as he struggled to release his harness. Mayor Renaud recalled, “About half a dozen Germans emptied the magazines of their sub-machine guns into him and the boy hung there with his eyes open, as though looking down at his own bullet holes.”

One paratrooper pulled his risers hard to slip away from the gunfire in the square but found himself drifting straight for the burning house. Having jumped from the plane so close to the ground, he had no time to maneuver and dropped into the inferno that was sucking in the air all around it; all the munitions he was carrying detonated.

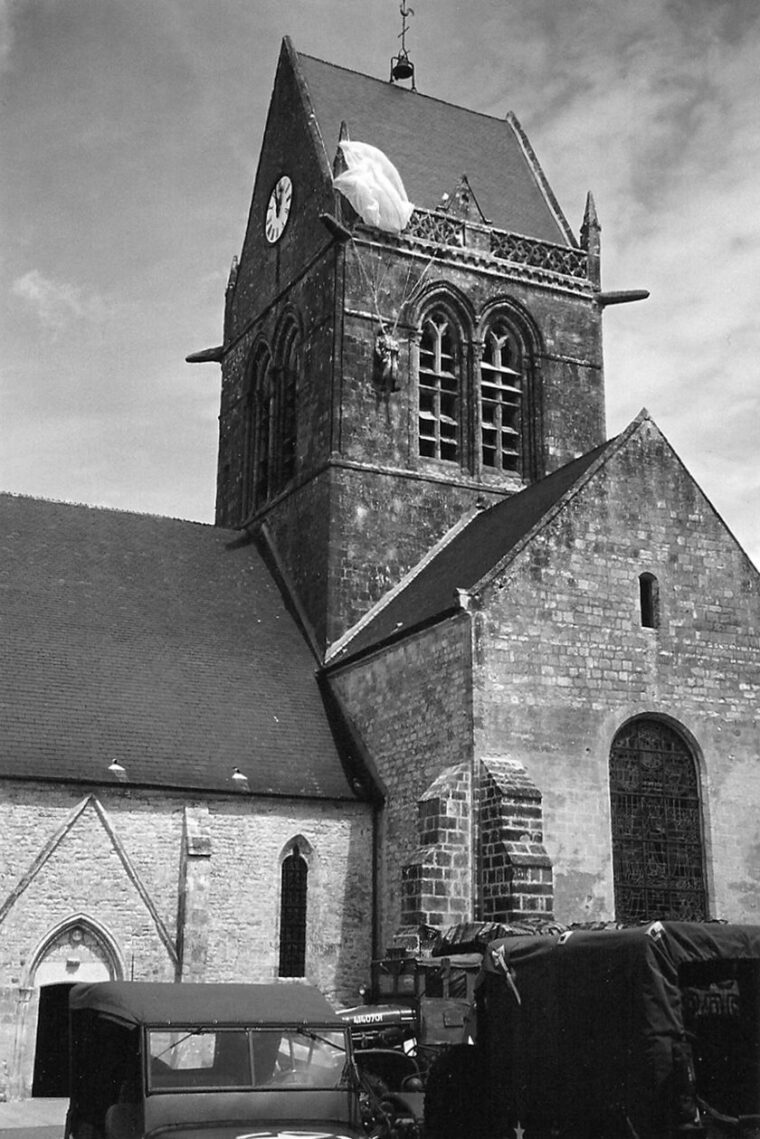

Another of the paratroopers, Private John Steele, a member of Wolf’s platoon, was shot in the foot as he descended, then got his canopy snagged on a corner of the church steeple and dangled there helplessly. With all the wild gunfire going on below him, Steele decided that the best thing he could do was play dead.

A German soldier, Corporal Rudolph May, was up in the church’s bell tower when the airborne attack came. Noticing Steele dangling outside one of the openings in the steeple, May said, “There was a man hanging there, suspended. He hung there like he was dead—but after a while he started moving. Then we also heard him sighing.” May’s comrade raised his weapon as if to shoot him, but May stopped him. He decided to try and cut the suspension lines of Steele’s chute. After he had cut several, he threw Steele a rope by which he could lower himself to the ground and be taken prisoner.

The exact number of paratroopers who came down in Sainte-Mère-Église is unknown, but Cornelius Ryan estimated it to be no more than 30, with about 20 of that number landing in and around the church square.

Lieutenant Colonel Ed Krause patted the pocket of his jump jacket to make sure it was still there. “It” was the flag he had raised over the Naples city hall eight months earlier and he had sworn to repeat that act here in Sainte-Mère-Église—if he lived to do so.

On the outskirts of town, Krause On the outskirts of town, Krause, from Green Bay, Wisconsin, and commander of 3rd Battalion, 505/82nd, surveyed the ville which, minutes before, had been in an uproar, what with a fire blazing, parachutists dropping here, there, and everywhere, and bullets flying.

One of those who landed with Krause’s battalion was Pfc. Leslie P. Cruise, Jr., H/505/82nd. He said, “We could hear sounds of machine-gun and rifle fire all around, but nothing was from our immediate location. We had secured our area and were waiting orders to move, which came after the confrontation with a civilian who had been convinced to join our group by a group of troopers. With the assistance of our newfound friend we moved out toward Sainte-Mère-Église with G Company in the lead, followed by H and I Company groups. Some groups were missing by the planeload, and we had no idea where they were, but we could not wait for them because time was very important to the success of the mission.”

K rause had nearly 200 men with him, hiding in the weeds and in the

hedgerows and behind buildings, preparing to enter the town. Without first making a house-to-house search, Krause and his men would slip into the town with their rifles empty, using only knives and grenades if they should encounter the enemy. That way, if any flashes were spotted in the dark, they would know it was the enemy doing the firing and be able to pinpoint the location. Krause knew that it was a dangerous gamble, but one he had to take.

Spencer Wurst made a hard landing in a field outside of Sainte-Mère-Église, hurting his back and hips. “If it had been a training jump,” he said, “I would have sought medical attention; I didn’t have that luxury. Before I even attempted to get out of my chute, I crawled over to the nearest hedgerow to get some cover. I pulled my pistol out, put it beside me, and went to work on the buckles of my chute.”

As he lay there, Wurst saw C-47s above him seemingly coming from all different directions and taking AA fire. He then saw a green star cluster. “This was the sign that someone in the battalion command group had reached the battalion assembly location.” With pain in his back and hips, he hobbled off in that direction and met up with his platoon leader, Lieutenant Joe Holcomb.

Despite the darkness at the battalion assembly point, Holcomb could see a standing paratrooper. Not wanting to give the position away, Holcomb told Wurst to tell that soldier to get down and take cover. Wurst said he hollered at the individual. “I don’t know about the politeness of the language I used. As the individual turned toward me, I saw two big stars. It was General Ridgway. That was the first and last time I tried to chew out the general.”

As a platoon commander in the 82nd, Lieutenant Vincent Wolf was supposed to be in charge of 40 men, but his platoon was scattered from hell to breakfast. Strangely, he didn’t mind. “If you had two or three guys together,” he explained, “it was a lot easier because you knew what you were going to do, instead of worrying about 30 or 40 other guys and what the hell they’re doing; you could get yourself lost in the dark a lot easier with 30 or 40 other guys. And if you have a small group and you see the enemy, it’s easier to knock them off with a knife.”

Wolf said that, after landing, “We cleaned out buildings, ran into groups of Germans who were well-trained—German paratroopers [6th Fallschirmjäger Regiment]—who were tough guys.”

Also moving toward Sainte-Mère-Église, Sergeant Otis Sampson, E/505/82nd, noted that the night sky was still filled with paratroopers. “Troopers came raining down to the rear of us,” he said. “My heart was in my throat, afraid that the first ones out would be hit by the lower-flying planes as they floated to earth, and there were some pretty close calls.”

At the battalion assembly point on the outskirts of town, Sampson came across the injured Lt. Col. Benjamin Vandervoort, his battalion commander. “He had his back against a wall and his legs outstretched,” Sampson said. “He filled me in, saying, ‘Some of the planes have become lost. I have sent out to gather what men and equipment we have; we’ve got the situation in hand.’ He paused for a spell and then said, ‘I came down quite hard on this leg,’ running his hand along his left one. ‘I’ve done something to it; I’ve sent for a medic.’”

Sampson said, “I could see he was in pain. There was nothing I could do for him, so I turned to go. ‘I’m proud to have you with us,’ he said as I walked away. It is me who should be telling him that, with a busted leg and still in control of the situation; it was a nice compliment.”

Spencer Wurst also saw Vandervoort. “He had broken his ankle in the jump and was hopping around on one leg, using a rifle as a crutch.” Broken leg or not, Vandervoort had come to France to fight and lead his battalion, and that was what he was going to do. The 505th’s exec officer, Mark Alexander, described Vandervoort as “a hell of a good battalion commander, but he was hard-headed as hell.”

Vincent Wolf recalled that Vandervoort “had a broken ankle but he wouldn’t let that slow him down. He was the greatest guy alive—great, great, great, great. We always called him ‘Ben,’ never ‘colonel.’ He’d give you a rap on the head if you saluted him in combat. I was the same way; I told my men ‘Never salute me,’ because that gives away to the enemy who the officers are, and then you’d get picked off by snipers. That’s what we did with the Germans. Once you knocked their non-coms off, the privates, hell, they didn’t know what to do. We could improvise a lot quicker than they could.

“I knew that we were supposed to free the French people, but I was more concerned about my men and me. The men first—where the hell were they? How many guys have survived? Out of the 18 that jumped with me, Russ Brown, my 60mm mortarman, he’s the only one that survived. There were Germans all around. It was a matter of survival—who saw who first.”

Vandervoort nabbed a couple of 101st men with a cart to haul him to his battalion’s objective. His mission was to get to Sainte-Mère-Église and that’s just what he intended to do, broken leg or not.

As Lt. Col. Krause’s group crept closer to the town, it looked like everything was over; the fire was out, the townsfolk had returned to their homes, and the German soldiers had also vacated the square by the big church, apparently thinking the battle was over, not just beginning. Smoke still filled the air and the bodies of dead paratroopers hung from trees and poles or lay sprawled on the pavement.

With stealth and silence the Americans slipped into town, found a building that was being used as a German barracks, and took 30 soldiers prisoner; 10 others were killed when they resisted. The Yanks also found the main communications cable to Cherbourg and destroyed it, then established a defense around the town’s perimeter.

Although he didn’t immediately know where he was other than somewhere in northern France, Duke Boswell did his best to round up other troopers. “My mission was just to get our group together and move into Sainte-Mère-Église. I put a flashlight on top of a pole—several sections that fit together—about 20 feet high. I think the lens was colored—red or green. The idea was to stick it in the ground so the troops could see it as an assembly point. We found somebody right quick-like, and then we got several more together. I assembled most of my squad and we got a few more and then one of the officers got there. The officer took charge and we went into Sainte-Mère-Église.

“We had certain positions around the town that we were to occupy, and the mission was to hold the village of Sainte-Mère-Église, well, not really the whole village, but the crossroads and a bridge to keep [German] reinforcements from getting to the beach and others at the beach from retreating. Seemed like our whole regiment was in and around Sainte-Mère-Église. We established our position on the edge of town on one of the roads. The first thing we saw when we got there were some of our guys hanging from the trees. They had jumped right over the town, and were shot before they could get out of their chutes.”

To hamper the Germans from returning to Sainte-Mère-Église, Pfc. Leslie Cruise and other paratroopers had set out mines on one of the roads leading into the city, then dug foxholes and set up firing positions to establish a roadblock. After the first gliders began landing in the area, Cruise heard equipment being off-loaded, followed by the sound of an American jeep being started. The jeep, with two soldiers in it, came tearing up the road toward Cruise’s position.

The paratroopers tried shouting to warn the jeep’s occupants of the roadblock and mines but the vehicle flew past them at a high rate of speed. Cruise said, “The occupants of the jeep were in a big hurry as we at the roadblock heard their running motor coming in our direction. Above all the noise, the distinct yells at the roadblock of ‘Hit the ground!’ were heard clearly and we all buried ourselves in the dirt of our foxholes. The driver must have thought our men were Germans and was not about to stop. Down the road they rode on full throttle.

“KAPOW ! BLOOEY ! BANG ! BOOM !—a deafening crescendo of explosives sounds as a number of our mines blew the jeep and its troopers into the air. All Hell broke loose—flashing lights with pieces of jeep and mine fragments raining down around us. Directly across the middle of our minefield they drove and immediately their direction became vertical, and in an arching skyward path they landed in the hedgerow beyond. We could hear the thump and bangs of falling parts all around us. The men had left the jeep on first impact and they had become the first casualties in our area, but they would not be the last. We had lost about half of our mines, which we had so carefully delivered, and they would be sorely needed in case the Krauts should attack. Those GI’s sure wrecked the hell out of our defenses.”

The defenders would indeed need the mines, for it wasn’t long before the Germans tried to retake the town.

The sky finally lightened to a gray overcast. Ben Vandervoort decided that he had assembled all of 2nd Battalion that he was likely to gather and so, with about 400 men, including some from the 101st, moved out cross-country toward Sainte-Mère-Église, sending out small patrols to farmhouses and barns to make sure that no German troops were lying in wait.

Lieutenant Wolf said, “We went into Sainte-Mère-Église. It was chaos for the simple reason that everybody was all over the place. We didn’t know who was who, who was supposed to do what, where the CP was. Total confusion.”

Otis Sampson recalled, “Orders were for us to take Sainte-Mère-Église. It wasn’t known at the time that the city had already been taken by Colonel Krause and was secure in his hands. It was early morning when our group came into the city with our colonel [Vandervoort] on a makeshift two-wheel stretcher. There were paratroopers still hanging from their chutes where they had been caught in the high trees before they could release themselves. Colonel Vandervoort’s first command: ‘Cut them down!’”

In the northern part of town, Krause’s American flag flew proudly from the city hall flagpole. Next door, at the large hospital/hospice, 505th surgeon Robert “Doc” Franco and his medics set up shop, caring for Americans, Germans, and civilians alike. “I was there from about 4 am until noon. During that time we treated about 30 or 40 casualties. Somebody came in and told me that about a mile away there was a farmhouse loaded with wounded guys. The family who lived there was doing the best they could to care for them. I walked to that farmhouse and, sure ‘nough, all around the outside there were dozens of wounded guys, some of them badly wounded. There were a few inside, too, in this large room. I was alone, with nobody to help me.” Franco himself would himself be wounded a few days later.

But if the Germans thought the onslaught ended with the paratroopers, they couldn’t have been more wrong; the glider force was on the way.

By the next day, June 7, Sainte-Mère-Église was still in 82nd Division hands, but no one knew how long the Yanks could hold if the Germans decided to counterattack in force. Vandervoort’s 2nd Battalion, 505th, was supposed to have moved up to Neuville-au-Plain to prevent the enemy from attacking from the north, but a German assault from the south compelled General Ridgway to order the bulk of 2nd Battalion to remain in Sainte-Mère-Église and reinforce Krause’s 3rd Battalion there. Vandervoort decided on his own, however, to send a reinforced platoon to Neuville-au-Plain to forestall any attack from that direction. General Gavin later called Vandervoort’s move “one of the best tactical decisions in the battle of Normandy,” for it was there that the Germans were gathering for a panzer-and-infantry assault.

First Lieutenant Turner B. Turnbull III, a half-Cherokee, took 44 men up the N-13 highway from Sainte-Mère-Église to Neuville-au-Plain, pushed out the German defenders, then prepared for the counterattack. Vandervoort, in a jeep towing a 57mm gun, joined him. Receiving word from a civilian that a group of paratroopers were approaching from the north with a captured self-propelled gun and a large number of German POWs, Turnbull and his colonel watched and waited. Before long, the group was seen coming down the road.

It was a trick. The “POWs” turned out to be well-armed Germans, and the “paratroopers” were either Germans in American uniforms that had been stripped from the dead or were real Americans who had been captured by the Germans. At any rate, the SP gun, and more behind it, began blasting Turnbull’s positions in Neuville-au-Plain, along with mortars and small arms. Vandervoort told Turnbull to delay the enemy for as long as possible, then withdraw back to Sainte-Mère-Église; the colonel then departed to alert the troops in Sainte-Mère-Église that the enemy was coming.

Turnbull’s men fought off the assault by the 1058th Infantry Regiment, reinforced, 91st Air-Landing Division. The battle lasted all day, with Turnbull’s outnumbered force giving as good as it got. At one point a soldier, Private John Atchley, manning a 57mm gun he had never fired before, knocked out a German SP gun, but the enemy was flanking the Americans on both sides. Sergeant Otis Sampson, located south of Neuville, personally dropped mortar rounds on the enemy threatening Turnbull’s platoon; his aim was on target and his platoon leader, Lieutenant Ted Peterson, called Sampson “the greatest and most accurate mortar sergeant in the business.”

At about 5 pm, the time came to withdraw, given the fact that Turnbull had only 16 effectives remaining out of his original number. But it was too late for him. Lieutenant James Coyle, E/505, recalled, “We engaged the enemy and prevented him from going any further in his plan of encirclement. We were able to hold them even though we were outnumbered, while Turnbull got his surviving men out of Neuville-au-Plain and on the way back to Sainte-Mère-Église.”

Turnbull never made it. Pfc. Stanley Kotlarz remembered a terrible shelling during the pull-back: “When [the shell] hit, all of us seemed to go up in the air. I got hit in the wrist and in the arm. A guy by the name of Brown got hit in the head. And Lieutenant Turnbull, it sheered the top of his head right off. When I got up, I saw Brown crawling away, staggering. Turnbull was lying there with his brains peeling out of his head.” For his valor, Turnbull received the Silver Star, posthumously.

The 82nd retook Neuville-au-Plain the following day with the help of armor that had landed at Utah Beach. Turnbull’s delaying action had given the 505th time to consolidate its position and likely saved the men in Sainte-Mère-Église.

Like the battles for scores of towns and villages in Normandy, the war passed through Sainte-Mère-Église, then moved on toward the east, leaving hundreds of dead and wounded—both combatants and civilians—in its wake. But the dead were, and are, remembered.

Chaplain Francis L. Sampson, 501/101st, reflected, “The French people of the little city of Sainte-Mère-Église had arranged that each family adopt a couple of graves [at the American military cemetery above Omaha Beach]. On Sundays and Holy Days they bedecked them with flowers, promising always to remember those soldiers in their prayers. This promise still holds good. American visitors to the cemetery are always moved by the sight of a French family placing fresh flowers on a grave or kneeling there offering their prayers for the soul of an adopted son or brother whom they had never seen in life.”

This article is adapted from Flint Whitlock’s latest book, If Chaos Reigns: The Near-Disaster and Ultimate Triumph of Allied Airborne Forces on D-Day, June 6, 1944 (Casemate, 2011).

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments