By Peter Kross

On February 1, 1943, a group called the U.S. Army Signal Intelligence Service, the forerunner of the modern-day National Security Agency (NSA), began a project to intercept and analyze diplomatic signal traffic sent by an ally of the United States: the Soviet Union. The undertaking went by the code name “Venona.”

Only in recent years has the NSA been releasing to the public portions of its voluminous files on the Venona Project, and what we are learning changes the way we look at our history in ways that could not have been thought of only years before. The Venona Project gives the modern-day historian a clearer view of just how much our wartime Soviet ally penetrated the U.S. government under the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, as well as our military and national defense industries, during World War II. The files also shed a bright light on the mentality of the Cold War that dominated U.S. foreign policy for almost 50 years.

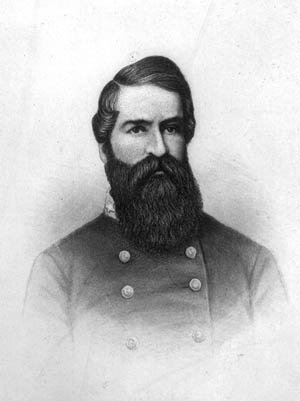

Carter Clarke’s Venona Project

Venona was the brainchild of Colonel Carter Clarke, the chief of the U.S. Army’s Special Branch, a division of the War Department’s Military Intelligence Division. During 1943, Colonel Clarke picked up signals that a possible Soviet-German peace deal was in the works, and he wanted to find out if the rumor was true. He ordered his small code-breaking unit to read all Soviet diplomatic traffic being sent from the United States to Moscow. The colonel’s crack team of code breakers was able to pick up copies of Soviet messages via international cable traffic being sent over the wires. Through hairsplitting months of trial and error, the analysts were able to crack the Soviet code. What they discovered was not information leading to a separate peace, but a massive Soviet espionage penetration operation of the highest levels of the American government.

The headquarters of the Venona Project was located in a remote site in Virginia called Arlington Hall. From this secure location, the code breakers worked on thousands of pages of cables being intercepted from Soviet diplomatic missions around the world.

The Soviet official entrusted in 1943 with handling these messages was Pavel Fitin, chief of the foreign intelligence directorate of the MGB (Ministry of State Security) in Moscow. Fitin ran five different espionage branches in the United States: (1) commercialties such as the Amtorg Trading Corporation handling all information coming from the U.S. Lend-Lease program to the Soviet Union; (2) the use of Soviet diplomats as intelligence agents; (3) direct relations with MGB headquarters in Moscow; (4) the running of the GRU-Soviet Army General Staff Intelligence Directorate (GRU, Soviet military intelligence); and (5) the GRU-Soviet Naval Intelligence Staff.

As time went on, the Legal Resident Agent at the Soviet embassy in Washington, D.C., Anatoli Gromov, who arrived in the United States in September 1944, took over intelligence duties. He was later to run a secret American spy unit operated by an American called Gregory Silvermaster. The files on Gromov say that he “was to take over the activities of the Government network following his arrival.”

By the time the Venona analysts were able to make headway in breaking Soviet traffic, the war had ended. But in the 1950s they learned that the Soviet Union, one of the United States’ main allies in World War II, had penetrated the super-secret Manhattan Project, in which U.S. scientists were working in total secrecy to develop the atomic bomb.

The Venona Discoveries

The year 1945 was pivotal as far as gathering information on Venona was concerned. In that year, a Soviet code clerk working in the Russian embassy in Ottawa, Canada, Igor Gouzenko, defected to Canadian authorities with hundreds of pages of top-secret documents. Gouzenko told the Canadians that the Soviets had a mole inside their intelligence system. He also named numerous officials who were working for the Soviet Union and passing national secrets. Among the names of alleged spies were such notable Roosevelt administration officials as Alger Hiss; Harry Dexter White, the second-highest-level person in the Treasury Department; Lauchlin Currie, one of FDR’s confidants; and the atomic espionage ring led by Julius Rosenberg.

The arrest of Julius Rosenberg would eventually lead to the jailing of his wife, Ethel; her brother, David Greenglass; Harry Gold; and British scientist Klaus Fuchs, among others. The Venona files include numerous files on all these individuals, as well as their cover names. These documents give historians a detailed report on just how all these people interacted with each other and the extent to which they were involved in espionage activities against the United States during the war.

Another prominent person who came forward to document the allegations made by Igor Gouzenko was Elizabeth Bentley, a former MGB courier in Washington.

Venona analysts were able to match the cover names originating from the Soviet cables to real people and places. For example, “Kapitan” was FDR, “Antenna” and “Liberal” were Julius Rosenberg, “Enormoz” was the Manhattan Project, “Babylon” was San Francisco, and “Good Girl” was Elizabeth Bentley, a plain, matronly woman in her mid-30s.

One of the best analysts at Arlington Hall in 1946 was Meredith Gardiner, who was able to decipher messages going between MGB headquarters in Moscow and their consulate in New York. Among the clues Gardiner found was the fact that the MGB had spies operating in Latin America and that they had many discussions about the 1944 U.S. presidential election. From 1947 to 1952, Arlington Hall analysts broke all Russian traffic between the Soviet Union and the United States. In 1953, U.S. code breakers were aided considerably in their work when they managed to get a copy of a partially burned Russian codebook relating to this message traffic.

Kim Philby Learns of Venona

The Soviets did have a general inkling of what the people at Arlington Hall were doing. When Elizabeth Bentley went over to the FBI with her information on Soviet espionage activities in the United States, she reported that British intelligence officer Kim Philby, a trusted World War II veteran of the British spy service and covert Russian agent, had given the Soviets some details concerning Venona back in 1944. When Philby was working in Washington in the early 1950s, he often went to Arlington Hall and met with American analysts, many of whom he befriended.

Besides the Manhattan Project, Venona was one of the most highly secret projects operating during World War II. The senior members of the Army and the FBI gave knowledge of Venona to only a privileged few people in the Roosevelt administration with a “need to know.” In fact, the CIA was not brought into the fold until 1952, and even then it did not receive all deciphered messages until 1953. Oddly enough, it was deemed that President Franklin D. Roosevelt did not have a “need to know.”

Keeping Venona Materials Secret

The declassified documents on the Venona Project that were not released to the public until the 1990s tell of the high-level intrigue and suspicion among the top intelligence branches of the American government during and after the war that caused them to limit the knowledge of Venona to only those people deemed able to share it.

One of the first messages inside the U.S. government relating to intelligence sharing of the Venona Project came in 1950 from a Mr. V.P. Keay to Alan Belmont, a high-ranking FBI official. In the memo, the writer said that a certain Captain Joseph Wenger, the deputy director of the Armed Forces Security Agency (AFSA), advised a Mr. Reynolds that a great deal of pressure was being brought to bear on an Admiral Stone, who was director of the AFSA, to distribute the Venona materials.

Mr. Keay wrote that General Carter Clarke, then the director of the Army Security Agency, had advised “Mr. Reynolds in extreme confidence that Admiral Stone had indicated a desire to disseminate [blank] material at least to the Central Intelligence Agency. At that time, General Clarke resisted the desires of Admiral Stone and was successful in having General [Omar] Bradley issue instructions to Admiral Stone that [blank] material would only be made available to the FBI. Captain Wenger suspects that the existence of [blank]. He stated that Admiral Stone does not know what the outcome will be but promised to keep Mr. Reynolds fully advised before any action is taken.”

The memo goes on to recommend that the FBI should not disseminate the Venona material to “any other American agency than the Bureau. General Bradley is advised as to the contents and, if a specific item is developed which either Admiral Stone or General Bradley believes should be made available to CIA or any other American agency, it might be handled as a special case and arrangements perfected that the information could be brought to the attention of the CIA without jeopardizing the source of information.”

Infighting Within the Intelligence Community

The infighting in Washington among the top military and law enforcement leaders about the dissemination of the Venona transcripts was ongoing during this period, and tempers flared among the participants. Two of these adversaries were the aforementioned General Clarke and Admiral Stone. According to the declassified documents in the Venona files, General Clarke was not too happy when he learned that Admiral Stone was being made privy to the work of the Army Security Agency regarding the Venona material. Admiral Stone believed that President Roosevelt and Admiral Roscoe Hillenkoetter, who would later become the first director of the newly created CIA beginning in May 1947, should be given access to Venona.

Just why President Roosevelt, the commander in chief of the armed forces of the United States, was not automatically on the list of Venona recipients is hard to fathom. But those in the loop deemed that, for some unexplained reason, FDR would not be made privy to Venona.

The files say that General Clarke “vehemently disagreed with Admiral Stone and advised the Admiral that he believed the only people entitled to know anything about this source were [blank] and the FBI.” In time, Clarke had a meeting with General Bradley, and the general agreed with his stand that “he would personally assume the responsibility of advising the President or anyone else in authority of the contents of this material if it so demands.”

It was determined that the FBI would handle all the Venona dissemination and that it would not provide this sensitive information to any other government organization or person without prior approval.

Keeping AFSA From the CIA

In May 1952, a meeting between certain members of the AFSA and the CIA was held to discuss the latest news concerning the Venona tapes. The representative of AFSA was Oliver Kirby, the assistant head of the Russian section of that agency. In a previous interview between two FBI agents and Mr. Kirby, he said that on May 20, 1952, he and Captain Jeffery Dennis, the head of the Russian section, had a meeting with Jason Paige and William Harvey, both of the CIA. The meeting was arranged by General Walter Bedell Smith of the CIA and General Ralph Canine of AFSA. Before the meeting took place, Captain Dennis was told by his superiors that “no collateral information received by AFSA from the Bureau was to be shown or discussed with the CIA representatives.”

At the meeting, the two CIA representatives were shown summaries of Venona messages but they did not include any identification made by the FBI. The CIA men said they were interested in receiving more information in regard to the penetration by the Soviets of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in 1944-1945. Mr. Harvey and his colleague were particularly interested in learning more about a British diplomat and secret Soviet spy named Donald MacLean (one of the so-called Cambridge Five), as well as information on a British scientist named Klaus Fuchs who had access to the super-secret Manhattan Project.

This meeting was long ranging and took about three and a half hours. Among the topics discussed was that the intercepted messages took place between New York and Moscow, and that other information was picked up between Canberra, Australia, and Moscow.

Mr. Kirby explained to the CIA representatives that AFSA was not “in the identification business”—rather, that was the job of the FBI and that he could not give that type of information to the CIA. “They tactfully suggested that such details would be available only through the Bureau.”

In his interview with FBI agents, Mr. Kirby said “he did not find it necessary to explain to the CIA the extent to which the material has been published and made available to the Bureau and he was not asked any such question. He said further that he was not asked, and did not tell the CIA representatives of the fact that the Bureau has furnished to AFSA in considerable detail the results of our investigations. He stated that the CIA representatives indicated that they intended to approach the Bureau regarding certain aspects of this problem.”

In an interesting aside, Mr. Kirby said that he did not inform Meredith Gardiner, one of the prime analysts at Arlington Hall who first broke the Venona files, about this meeting because “he did not want Gardiner placed in the position of having to answer questions regarding the extent of the material and the identifications made from the material.”

Limited Access For the CIA

This was not the last episode that both sides would have in their ongoing feud over the sharing of the Venona materials.

By June 1952, a tentative agreement by the CIA and the FBI was cemented in order for the latter to be given certain access to Venona materials. An internal memo inside the FBI written by Alan Belmont to Mr. D.M. Ladd specified what types of information the CIA would get. The CIA wanted information relating to MGB penetration of the OSS and cases where the CIA had a real interest.

After much haggling, an agreement to share information with the CIA was hashed out by General Smith of the CIA and General Canine of AFSA. The intelligence that was to be provided to the CIA related to “activities of the MGB in the United States and relates to a limited degree to MGB activities in other countries.” This information was provided to William Harvey and Jason Paige, who had previously met with representatives of AFSA. Harvey said that he needed information on former employees of the OSS who had been secretly working for the Russians, even though the FBI was reluctant to provide such material. It was finally agreed that any discussions with the CIA should be restrictive and limited to these two categories in order to ensure that no further secrets would be inadvertently revealed.

As vice president, Harry Truman was not made privy to the Venona transcripts, and after the death of President Roosevelt in April 1945, he still wasn’t fully informed of all the details of the program. He was, however, given routine debriefings on the most important aspects of the materials on a regular basis.

J. Edgar Hoover and Venona

One person who did have total access to the Venona decrypts was FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. He was apprised of the details in a memo written by FBI agent Ladd in the spring of 1951. In the memo, he was informed that the FBI was investigating Soviet penetration operations against the United States from April 1944 to May 1945. He was told, however, that the initial FBI inquest showed that MGB agents had been involved in their spying activities many years later. The most important aspect of the memo was that the Soviets were mainly interested in gathering as much information as they could on the United States’ atomic energy program (i.e., the Manhattan Project). Other important aspects relating to the MGB were the infiltration of the U.S. government and the infiltration of Trotskyite and White Russian activities.

Hoover was told that the FBI had a source who provided them with much of their information pertaining to Venona, but often it was “fragmentary and, in addition, the Soviet’s extensive use of code names makes identification difficult.”

Hoover was further informed that the FBI had positively identified 108 people who were involved in Soviet espionage activities, that 44 others had been further identified by other sources, and that 64 people were still unknown. An additional 64 people whose names were previously not known were now under investigation.

Harry Dexter White: Code-Name “Jurist”

The most important aspect of the Venona files was the identification of many members of the Roosevelt administration who were secretly spying for the Soviet Union during World War II. Many of these people were confidants of the president and had considerable influence in the administration.

One of these men was code-named “Jurist,” who was identified as presidential adviser Harry Dexter White, once the administrative assistant to the former secretary of the treasury. White operated in 1944, and the Venona transcripts say that he reported to the Soviets on a conversation between then Secretary of State Cordell Hull and Vice President Henry Wallace; he also reported on Wallace’s trip to China. “On August 5, 1944,” the transcripts say, “he reported to the Soviets that he was confident of President Roosevelt’s victory in the coming elections unless there was a huge military failure. He also reported that Truman’s nomination as Vice President was calculated to secure the vote of the conservative wing of the Democratic party.” It was also mentioned that Jurist was willing to perform any self-sacrifice on behalf of the MGB but was afraid that his activities, if exposed, might lead to a political scandal and have “an effect on the elections.”

In 1937, White worked as the assistant director of the Division of Monetary Research in the Treasury Department. Although White was an informer for the Soviet Union, he was not a “card-carrying” member of the Communist Party of the United States—just one who was loyal to its cause. White’s Soviet controllers were often annoyed with him, saying that he wasn’t providing enough valuable intelligence for them, but the spy, or “mole,” consistently gave them as much information as he could.

Theodore Hall

The files also show intelligence interest in a young scientist named Theodore Hall who came to their attention in November 1944 when he made a trip to New York, probably to see his MGB controllers. Hall was working as a physicist at the secret atomic bomb research facility in Los Alamos, New Mexico, as one of the wunderkinds on the project. He was a supplier of information for the MGB, which now had a pipeline into the most secret U.S. government project. Hall used an intermediary named “Beck” who, in turn, gave the data to another person named Saville Sax, who forwarded it to the Soviet consulate.

When Hall first approached the Russians, a member of the American Communist Party named Bernard Schuster did a background check on him, and Hall was brought into the fold. In all, there were eight Venona cables referring to Hall’s espionage activities, beginning with his recruitment in November 1944 through his work at Los Alamos ending in July 1945. Hall was a brilliant young man, having graduated from Harvard at age 18. When Hall arrived in New York on leave from Los Alamos, he contacted his old roommate, Saville Sax, another Russian sympathizer. While in New York, Sax contacted the MGB, told them about his friend Hall, and became intertwined in the plots against the United States regarding the Manhattan Project. Sax traveled to New Mexico, where he picked up information provided to him by Hall. The names Theodore Hall and Saville Sax were a huge find for modern-day historians when the Venona files were finally declassified.

Soviet Spies in the OSS

The Russians made their most important penetration of the U.S. government when they planted high-level agents in the OSS—the United States’ elite intelligence-gathering organization—during World War II. At the start of the war, the United States had no organized intelligence services and in the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack, that task proved to be the number one item on FDR’s agenda.

The OSS was headed by William Donovan, a World War I Medal of Honor recipient, New York lawyer, and Republican. FDR knew Donovan from his stint in New York politics, and although Donovan was in the opposition party, the president respected him for his integrity and honor. When he started the OSS, Donovan was not particular whom he hired; he was looking for the best and brightest—men and women who could do the job without asking too many questions. In that regard, Donovan hired a number of people who had Communist leanings, if not outright sympathizers. The Venona transcripts reveal that at least a dozen people employed at the OSS were Communist sympathizers who provided the MGB with valuable information during the war.

Among them were Donald Wheeler, one of their most important assets and a former Treasury employee. Wheeler worked on German issues for the OSS and passed his information to the New York Soviet resident. The MGB said that Wheeler was of “especially great interest” and that the information he sent was “a rich source of material” on Germany’s economic program. The OSS soon realized that Wheeler was a Communist but decided to let him remain in his position. Wheeler provided the Soviets with the names of a number of OSS agents and ultimately left the OSS for the State Department. His identity as a Soviet mole was given to the FBI by Elizabeth Bentley, a high-ranking Soviet mole who changed sides and became a reliable source for the FBI. Bentley was responsible for unearthing a number of high-profile American government agents who were secretly employed by the OSS as well as other government departments.

Duncan Lee was a Yale graduate and a lawyer who worked for Bill Donovan’s law firm before joining the OSS. He joined the OSS in 1943 and also reported to Elizabeth Bentley whom he knew only by her code name, “Helen.” He supplied the Russians with information on the OSS’s relationship with Polish intelligence, but at times his intelligence take was not what the Russians were looking for. Bentley later told the FBI that Lee was not really eager to work with the Russians for fear of being arrested by the FBI. After Bentley’s defection, the Russians deactivated Lee in 1945.

Franz Neumann, code-named “Ruff” by the Soviets, worked in the OSS’s foreign division and supplied the Russians with information from various American foreign diplomats to Washington. From his position at the Research and Analysis Branch of OSS, Neumann provided the Soviets with personal communications from American ambassadors serving in overseas posts to OSS headquarters. However, by 1943, the Russians wrote that “Ruff does practically nothing” but was instrumental in informing the Russians that Allen Dulles was speaking with certain members of the German underground who were planning to overthrow Hitler. After his service at the OSS, Neumann joined the staff of the Nuremberg War Crime Trials and moved to Germany after the war.

Alger Hiss: Code-Name “Ales”

Among the declassified Venona transcripts, the ones that most changed the way modern-day historians look at the Cold War revolved around Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and Alger Hiss, whose cases dominated the postwar era and highlighted the so-called McCarthy era in 1950s America. This article cannot describe in total the entire Rosenberg-Hiss cases because of space constraints, but the most relevant material released in the Venona files makes for fascinating reading and does much to explain that McCarthy’s efforts to root out Communists in government, although later discredited, weren’t all a matter of paranoia.

Alger Hiss had been one of America’s most respected diplomats, serving in Washington since the 1930s. For members of that generation, his name invokes memories of a time when the Communist threat seemed to be just around the corner.

The fallout from the Hiss case pitted liberals and conservatives against each other—a battle that continues to this day. Now, almost 60 years after the trial of Alger Hiss, new revelations may finally put to rest the question of whether Hiss was an agent for the Soviet Union during and after World War II.

A number of the Venona cables implicated Hiss as a Soviet asset who went by the code name “Ales.” The files also report a meeting between a KGB officer and a GRU officer whose source in Washington was “Ales.” Another file linking Hiss to Soviet intelligence comes from a cable to Moscow from its agent “Vadim”—who was, in reality, Anatoli Gromov, the station chief of the NKVD (the forerunner of the KGB), in which he reports a conversation between agent “A” and “Ales.”

The Venona files say that “A” was Iskhak Akhmerov, one of the most important Soviet spies in the United States during the war. This same intercept says that “Ales” had been working for the Soviets since 1935. The files buttress the Hiss-Russia relationship in that “Ales functioned as the leader of a small group of neighbors probationers, for the most part consisting of his relations.” (In the Venona transcripts, “neighbors” refers to members of the American Communist Party.) The tapes also say that “Ales” went on a separate trip to Moscow after the Big Three meeting in Yalta in February 1945. The record proves that Hiss went to the Soviet capital on a plane carrying U.S. Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, along with two other career diplomats.

With the release of the Venona files, it now seems that historians finally have answered the riddle of what role Alger Hiss played during World War II and the Cold War. However, partisans on both sides of the political divide will undoubtedly interpret the newly released files with an eye toward vindication for their own point of view.

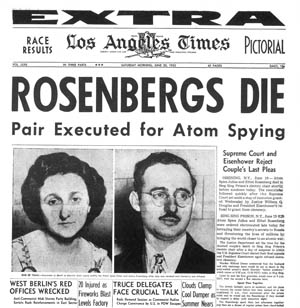

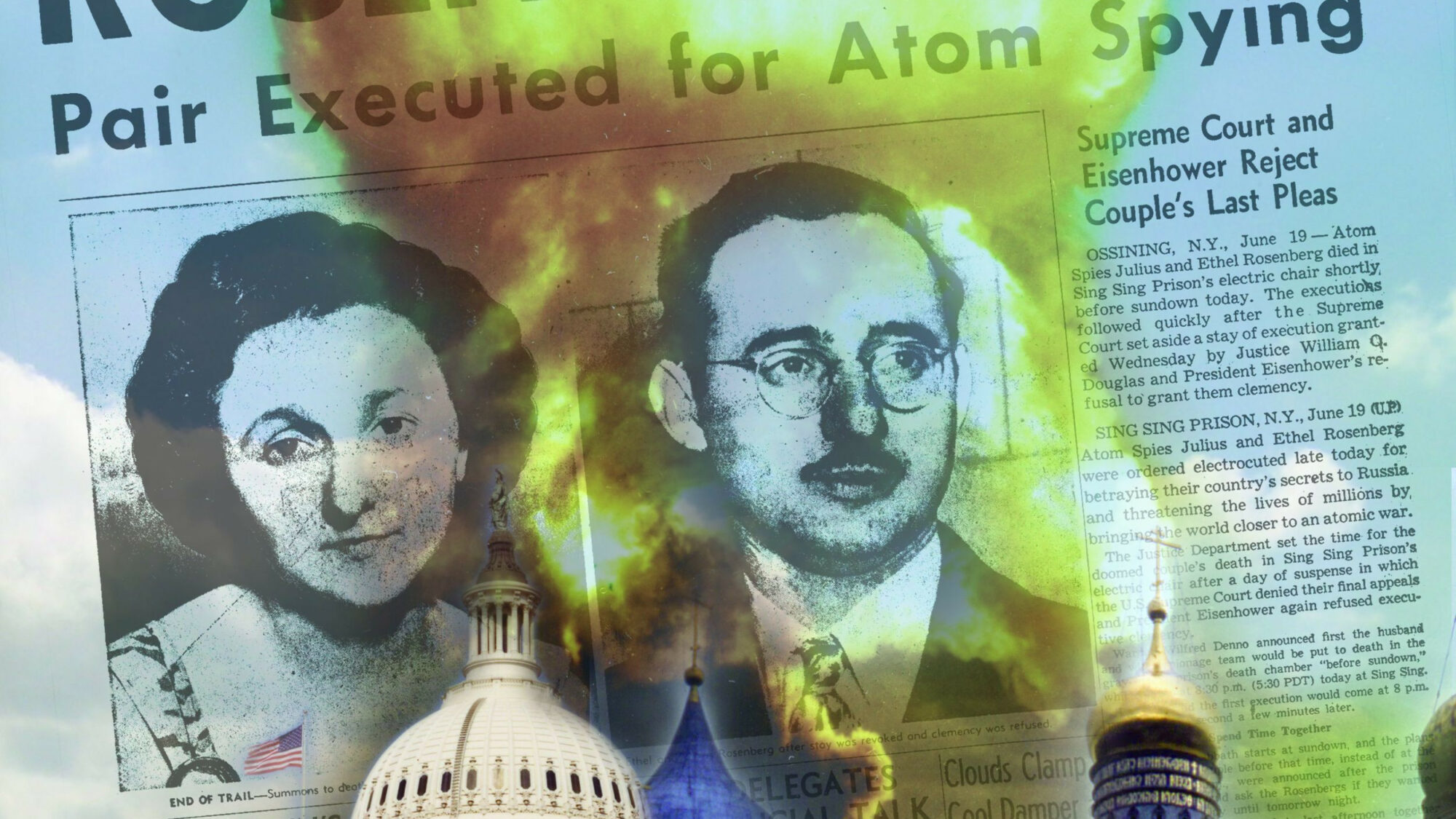

The Controversial Rosenberg Trial

Fifty-eight years have passed since the June 19, 1953, execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in Sing Sing prison on espionage charges for their involvement in stealing America’s atomic secrets during World War II––a case that still creates passionate debate over their death sentences and to what extent they were both involved with the Soviet Union’s espionage operations. With the end of the Cold War, America’s most prominent code-breaking service, the National Security Agency, as well as a former Soviet intelligence officer who knew the Rosenbergs well, have shed new light on the role they performed for the Soviets during the war.

The Russians gave Julius Rosenberg two code names: “Antenna” and “Liberal.” From 1944 to 1945, the Venona analysts picked up 21 cables referring to him. They learned that by May 22, 1944, Rosenberg’s spy network operating out of New York City was flourishing. Julius recruited Alfred Sarant, a classmate at CCNY who had previously worked at the Signal Corps laboratory at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey.

The early Venona files also report that the Russians provided Julius with his own camera in order to copy stolen documents at his home. Additionally, Rosenberg recruited a man named Russell McNutt, code-named “Fogel,” who was a civil engineer at the Oak Ridge, Tennessee, plant that made components for the atomic bomb. In 1944 the KGB said that McNutt’s recruitment was “one of the year’s main achievements.”

Julius also brought into his spy cell friends and colleagues such as Morton Sobell, William Pearl, and his wife’s brother, David Greenglass. Another person who aided Rosenberg was an American soldier named Harry Gold who was an intelligence operative and courier for the Soviet GRU.

A retired Russian spy who was close to the couple during the war, Alexander Feklisov, provided more information on Ethel and Julius Rosenberg’s wartime espionage activities. In 1977, Feklisov gave a number of high-profile interviews to American news organizations regarding his knowledge of the Rosenberg case. He said he met with Julius in the summer of 1946 in a New York restaurant and gave him $1,000 in expense money. Prior to that date, Feklisov said that, between 1943 and 1946, he met with Julius in New York more than 50 times, helping him to establish his espionage network.

He emphatically told his interviewers that although Ethel Rosenberg was aware of her husband’s work for the Russians, she had no direct contact with any member of Soviet intelligence. Of Ethel Rosenberg, the Venona documents say that she “knows about her husband’s work, but is in delicate health and does not work.” When questioned about Julius’s role in stealing America’s atomic secrets, Feklisov said that he played only a minor role in the affair.

The new information provided by the Venona transcripts, as well as by Alexander Feklisov, adds new details to the case. The Rosenbergs’ sensational trial and execution came at a time in American history when Cold War hysteria and McCarthyism were at their height. Whether they were its first victims or pawns in a larger game of Cold War politics is still being debated.

3,000 Letters to U.S. Spies

By the time the Venona project ended, more than 3,000 letters from the Soviet Union to their personnel in the United States had been read. The Freedom of Information Act led to the opening of the Venona files, and in 1995 the world learned of its contents.

Who knows what other historical treasures are still hidden in the vaults of the National Archives that may yet still shed more light on the secrets of our Cold War past?

President Truman didn’t receive ‘debriefings’. He received briefings. When you have gone somewhere or have done something and are asked about what happened, that’s a debriefing. In a debriefing, you are the one providing the information. See this mistake made all too often.