By Leo Barron

Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr., the commander of the newly constituted U.S. Third Army, had one simple order that late summer of 1944: “Go east and go like Hell.” That directive would pit him against Manteuffel’s panzers in late September during the Battle of Arracourt.

Since the beginning of August that year, Patton’s tanks had rolled through France, cutting up retreating German units while bypassing enemy strongpoints. Patton’s swift advance had been an unmitigated disaster for the German Army. Hitler had hoped that his Aryan supermen could bottle up the Allied juggernaut inside the Normandy beachhead for the rest of the year. Alas, Operation Cobra shattered his hopes, and by the first week of August, American troops were racing eastward toward Germany.

Suddenly, disaster loomed for the Germans along the entire Western Front. Instead of a war of attrition, the Allies had turned the conflict into a war of maneuver. This type of warfare favored the Allies, whose armies, thanks to American industry, were almost completely motorized, while the German Army still relied heavily on horse-drawn transport. Because of this mechanization, the Allies were outrunning the withdrawing German forces. Inside the Falaise Pocket, over 50,000 German soldiers surrendered and thousands more died after Allied forces had outflanked and surrounded them.

By the end of August, Patton’s divisions were closing in on the German frontier. All that stood between the tanks of “Old Blood and Guts” and Germany were the remnants of several tattered German armies. To the GIs, it seemed like they would be in Berlin by October. Unfortunately, tanks require gas, and on September 1, the Third Army ran out. The great race came to a screeching halt. Patton’s soldiers had traveled over 300 miles since the beginning of August and were now within 100 miles of the Rhine River.

The German high command welcomed the unexpected halt and began to rush units to the frontier while preparing the West Wall, or Siegfried Line, for the inevitable showdown. The Germans did not know how much time they had before the Americans resumed the offensive. Accordingly, Hitler ordered Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) to shift newly constituted units originally destined for the Eastern Front westward instead. Even though Hitler had lost countless divisions in Operation Bagration in eastern Poland, he felt he could trade land for time in the East. He did not have that luxury in the West. Once the Allies crossed the Rhine, it would only be a matter time before they captured the Ruhr, the industrial heart of Germany, and the Saar River region of the Reich. Hitler could not afford to lose either. He had to stop Patton’s steamroller somewhere.

The Germans Panzer Brigades: Powerful But Flawed

The Führer’s solution lay in his reliable panzer brigades. Panzer brigades were stopgap measures originally designed for the Eastern Front. Like a panzer division, these brigades had two battalions of panzers. One battalion had long-barreled Mark IVs, while the other operated Mark V Panthers. Each type mounted a high-velocity 75mm cannon. Unlike a typical panzer battalion within a division that had four panzer companies, each battalion in these panzer brigades had three companies, and each company had three platoons.

At full strength, each platoon had four panzers, and each company command section had two panzers, bringing each company’s total to 14. Together, each battalion had over 40 panzers, and each brigade had over 80 panzers at full strength. According to General Horst Stumpff, “The three brigades [111-113] were consequently—measured by Western Front standards at that time—extraordinarily well equipped with armor.”

However, unlike the panzer divisions, the panzer brigades had only one regiment of panzergrenadiers. The single panzergrenadier regiment had two battalions, each with three motorized infantry companies. While a standard panzer division had four battalions of infantry, the panzer brigade had half that number. The panzer brigades also lacked an artillery regiment. Hence, they had to rely on corps assets for indirect fire support. Even worse, each brigade had only one reconnaissance troop with just two platoons, while a panzer division typically had an entire squadron of reconnaissance vehicles with five scout troops. Bereft of reconnaissance units, the panzer brigades would likely be bumbling around the battlefield blind. This lack of resources would come back to haunt them.

The shortages of artillery tubes and reconnaissance units were not the only shortcomings hampering the panzer brigades. They also were deficient in headquarters staff. General Stumpff later wrote, “The brigade staff consisted in fact of only one armored infantry regimental headquarters and therefore did not have the means of signal communications with [the] armored units. The brigade commanders were obliged to take part in the tank attack in order to ensure their control whereby they became conspicuous in their armored personnel carriers and drew fire upon themselves.”

The most glaring issue facing the Germans was the lack of trained soldiers and leaders. Most of the noncommissioned officers were from replacement and training units, while the majority of the junior officers were infantry officers. According to Stumpff, these junior officers “had no idea of the commitment of motorized formations.” Even worse, the panzer brigades “were organized just at their points of assembly immediately behind the front line, and had, therefore, never been able to hold combined exercises and give the commanders experience.”

Patton’s Third Army: Battle-Hardened But Outgunned

Facing these newly constituted panzer formations with their lack of resources and lack of trained personnel were the armored divisions of Patton’s Third Army. Leading the way was the 4th Armored Division under the command of Maj. Gen. John S. Wood. In contrast to the new panzer crews and panzergrenadiers in the panzer brigades, many of the tankers and infantrymen of the 4th Armored Division had been training together since 1941. Moreover, the division had been fighting almost nonstop since mid-July. These armored formations were battle hardened and at the top of their game.

Unfortunately, many of the tanks in the 4th Armored were the ubiquitous M4 Sherman, which mounted a short-barreled 75mm gun. Against the long-barreled Mark IVs and Mark V Panthers, the M4 was at a distinct disadvantage. Its gun had a lower muzzle velocity and could not penetrate the frontal armor of a Mark IV at distances greater than 1,000 meters. Against a Panther, the disparity was even worse. The M4’s stubby 75mm had trouble penetrating the front glacis of a Panther even at point-blank range. In contrast, the 75mm KwK 42 of the Mark V Panther could penetrate the frontal armor of a Sherman from 2,000 meters. In the ensuing battle, one question was at the forefront. Would American training and organization overcome German technology?

Crossing the Moselle

On September 5, 1944, Patton found some gasoline for his tanks and ordered his XII Corps, under the command of Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy, to push across the Moselle River and head east toward the Rhine. Eddy instructed his 80th Infantry Division to leap the river north of Nancy, France, but the German defenders threw the 80th back with little trouble. It was obvious now to Eddy that the Germans had used their down time wisely while the Americans were securing supplies.

Crossing the Moselle River would now require all of the corps assets. General Eddy and General Wood devised a plan. On September 11, the 80th Infantry Division would cross north of Nancy near the town of Dieulouard, while the other two divisions, the 4th Armored (minus Combat Command A) and the 35th Infantry Division, would cross the Moselle south of Nancy. In the meantime, Combat Command A, under Colonel Bruce C. Clarke, would act as corps reserve, waiting to exploit any potential breakthrough.

Clarke’s Combat Command A (CCA) was one of the three combat commands in the 4th Armored Division. Each combat command in an American armored division would usually have one armored artillery battalion, one armored infantry battalion, and one tank battalion. In CCA’s case, Clarke had the 37th Tank Battalion under the command of Lt. Col. Creighton W. Abrams. Clarke also had several units attached to his command, including a company of tank destroyers from the 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion under Captain Thomas J. Evans.

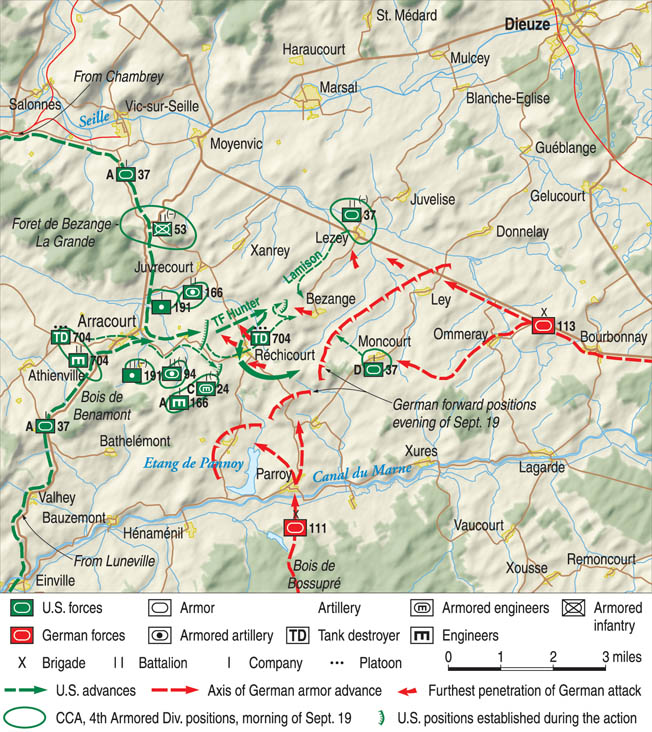

On September 13, CCA crossed the Moselle at Dieulouard after the 80th Infantry Division had established a bridgehead as planned two days earlier. To the south of Nancy, the 35th Infantry Division and the rest of the 4th Armored Division had crossed the Moselle on the 11th. For several days, CCA pushed deeper into German-held territory. By the evening of the 18th, it was firmly entrenched along the east side of the Moselle, concentrating near the town of Arracourt, France. The appearance of U.S. armored units east of the river sent shockwaves throughout the German high command.

Unknown to Patton, his constant hammering against the German lines had led to a penetration between two German armies, the Nineteenth to the south and the First to the north. It was a dangerous situation, and neither army was in position to close the gap. Once again, Patton’s tanks were poised to break through and spread havoc in the German operational support areas.

Manteuffel’s Counterattack

Both German armies fell under the command of Army Group G. Realizing the precariousness of the situation, Col. Gen. Johannes Blaskowitz, the commander of Army Group G, had no choice but to commit the newly reorganized Fifth Panzer Army to battle under the command of General Hasso von Manteuffel. For Manteuffel and Blaskowitz, the only realistic option was a massive counterattack. Unlike the First and Nineteenth Armies, which were woefully understrength, Fifth Panzer Army had three new panzer brigades: the 111th, 112th, and 113th. Blaskowitz chose Manteuffel’s command to conduct the operation for that very reason. Furthermore, there was no time to establish a new defensive line east of the Moselle. Manteuffel had to stop Patton or at least delay him before Third Army reached the German border near the Saar, and before the Americans were able to turn the flank of the German First Army.

Manteuffel then selected two panzer corps to lead the attack. His southern strike force would be the XXXXVII Panzer Corps under Maj. Gen. Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz. The XXXXVII Panzer Corps’ attack would comprise the 112th Panzer Brigade and the 21st Panzer Division. Once the corps reached its area of operations, the understrength 15th Panzergrenadier Division would also fall under its command. The corps mission was to recapture the town of Luneville, which had fallen to the U.S. XII Corps on September 16, and then proceed to the Rhine-Marne Canal, severing the American salient.

To the north would be the LVIII Panzer Corps under General Walter Krüger. His corps attack force would comprise the 111th and 113th Panzer Brigades. Its mission “was to delay the enemy [CCA] advance as far to the west as possible [and] … north of the Rhine-Marne Canal with the 113th Panzer Brigade….” While the southern strike force planned to attack on the 18th, the northern strike force would push toward Xousse, France, and develop the situation. Facing this massive panzer onslaught in the north was CCA, with its single battalion of tanks.

Krüger watched the operation run into trouble almost immediately. The 111th Panzer Brigade was late arriving, leaving the 113th to tangle with American armored reconnaissance elements alone. In spite of this setback, the 113th Panzer Brigade still had more than enough combat power to overwhelm CCA, and the American forces, according to Krüger, “fell back toward the southwest.”

By the evening of the 18th, Krüger still did not have a clear idea of the enemy strength in front of his forces. The 113th’s lack of reconnaissance units was beginning to hamper the operation. Despite the absence of the 111th Panzer Brigade, the corps commander knew he had to press on, and he ordered the 113th, under Colonel Freiherr von Seckendorff, “to take possession of the high terrain of Rechicourt-le-Petite and to make observations to the west from that spot in order to control this sector even before the arrival of the 111th Panzer Brigade and in order to maintain, at least, liaison by reconnaissance with the right wing of the 15th Panzergrenadier Division near Hananenil.”

Preparing For Panzers

Opposite Krüger’s panzers, the Americans prepared to bed down for the night, but not everyone was sleeping soundly. First Lieutenant Wilbur J. Berard, leading 2nd Platoon, Charlie Company, 37th Tank Battalion, sensed trouble. It was 9 pm on September 18, and one of his soldiers, Staff Sergeant Timothy J. Dunn, had just reported that he could hear the gurgling and humming of German panzer engines southeast of his position near the town of Lezey, France. Dunn knew the tanks were German because a local villager had told him that he had seen six tanks earlier in the day near the town of Ley, just two kilometers southeast of Lezey.

Luckily, Berard had positioned his three tanks for just such an engagement. Earlier that afternoon, he had placed one Sherman, under the command of Sergeant Earl S. Radular, north of the road that linked Lezey with Bourdonnay. Radular did not want his vehicle exposed, so he backed it into a gully, providing cover and concealment. Berard had positioned his own tank and Dunn’s M4 south of the same road. The seasoned lieutenant had hidden his tank behind some bushes while Dunn’s tank occupied a high point to observe the entire area. All three oriented their guns toward the last known position of the panzers near the town of Ley.

To prevent the Germans from flanking to the east, Dunn laid 12 mines across the Lezey-Bourdonnay highway. After reporting to higher command about the possible panzers, Berard coordinated with the 94th Armored Field Artillery to conduct harassment and interdiction fire missions on likely German locations. Then they waited.

The following morning, a dense fog hung over the valley. Despite the limited visibility, Berard still could hear the tanks southeast of his position. He reported the news to his commander, Captain Kenneth R. Lamison. Lamison immediately dispatched the rest of 2nd Platoon to join Berard. Lamison also reinforced his company picket line around Lezey with 1st Platoon, under the command of 2nd Lt. Howard L. Smith. The 1st Section of 1st Platoon occupied a position south of Lezey, while the 2nd Section relieved the other section of 2nd Platoon, west of the town. The reunited sections of 2nd Platoon, minus Dunn’s tank, moved north of the Lezey-Bourdonnay highway.

While Lamison arranged his forces, a platoon of M5 light tanks from Dog Company detected one of the few reconnaissance units from the 113th Panzer Brigade. The platoon spotted the German half-tracks near the town of Montcourt. When the tankers identified the vehicles appearing in front of them as the enemy, they opened fire, destroying one half-track. As light tanks were susceptible to catastrophic damage, they quickly withdrew to the west, only stopping to pop off a few rounds at the Germans and buying time for the rest of the battalion. After all the positioning, this engagement signaled the beginning of the Battle of Arracourt.

First Engagement at the Battle of Arracourt

Smith’s 1st Section was the first element in Charlie Company to engage the enemy. One of the company’s tanks was west of the north-south road, and the other was tucked away in a barn, camouflaged under some straw. Both tank gunners could see the road that connected Lezey with Bezange, just south of their location. In an effort to provide early warning, the tankers had dismounted a team to man a forward observation post. The team communicated with the tanks by a telephone hooked up to a single wire that led back to the tank. It was an effective tactic, and it paid off that morning.

Suddenly, around 7 am, Smith’s observation post spotted several Panthers as they emerged from the fog. They approached Smith’s platoon from the direction of Bezange at a distance of less than 75 meters. The observation post telephoned back to the M4 crews, who were waiting for the unsuspecting Panthers. Within seconds, the two M4s opened fire. At such a short distance, the stubby 75mm guns could not miss. Almost immediately, two of the lead Panthers brewed up. The other German tank crews realized it was an ambush, and they began to back away into the mist.

Sergeant Dunn saw the firefight from his position east of Lezey and ordered his gunner to swing south toward Bezange. The Panthers were the lead elements of 1st Battalion, 130th Panzer Regiment. This battalion was one of two from the 113th Panzer Brigade. Dunn could probably care less what unit the Panthers belonged to. He just knew he had to kill them before they slew his tank. At approximately 600 meters, Dunn opened fire on a third Panther as it attempted to escape. It took three rounds from Dunn’s tank, but the hapless Panther started to smoke and burn. Dunn watched several of the crewmen clamber out of the tank to escape the fiery deathtrap.

Captain Lamison’s Ambush

Captain Lamison now knew where the enemy was. In response, he ordered Smith’s 1st Platoon to consolidate south of Lezey. Lamison sent the 2nd Section of 3rd Platoon to occupy the now vacant position west of Lezey. Meanwhile, the Charlie Company commander decided to cut off the retreating German column. Between the last the section of 3rd Platoon and his own headquarters element, Lamison had four tanks at his disposal. He quickly scanned the map and realized the best place to interdict the column was a ridgeline west of Bezange. He shouted at his driver to head south, skirting the military crest of the ridge. It was a race.

The speed of the Sherman tank afforded Lamison an advantage. He outran the lumbering column of Panthers and reached an attack position west of Bezange three minutes before the slow-moving panzers passed through the village. From his location along the ridge, Lamison’s tank crews had perfect flank shots on the column, while the crest provided the M4s with natural cover.

Lamison waited for the best shot. Crack! His 75mm cannon opened fire, and his fellow tankers quickly fired their own main guns, adding to the fiery fusillade. With their flanks exposed, the Panthers did not have a chance. One by one, the vulnerable German tanks started to pop and explode.

Lamison’s hasty ambush highlighted another deficiency in the German tanks. The Sherman had a more powerful motor on the turret traverse mechanism, and therefore the Sherman’s turret traversed faster than the Panther’s. The result was that a Sherman tank crew could lay its gun on a target quicker than its German adversary. This lesson was made painfully clear that September morning. When the first Panther finally returned fire, Lamison estimated his makeshift team already had destroyed five enemy tanks. Only three Panthers remained.

Sensing victory, Lamison pressed the issue. He ducked his tanks behind the ridge and then rushed south to another position. His four tanks then popped up from behind the crest and opened fire on the last three panzers still in Bezange, destroying all three. Before they could celebrate, a concealed Pak 40, a towed 75mm antitank gun from one of the weapons companies in the 2113th Panzergrenadier Regiment, blasted away at Lamison’s team from an unknown location near the village. With rounds skipping past their tanks, the drivers once again backed their M4s behind the crest.

The Charlie Company commander climbed out of his tank to search for the pesky gun on foot. After several minutes, he found it and directed his tankers to open fire on its location. No longer the hunter but the hunted, the gun crew labored to pull the weapon to safety. However, the Germans were unsuccessful, and Lamison’s tanks destroyed it. The battle, though, was far from over.

Four Panzers Knocked Out

East of Lezey, another column of German panzers approached Lieutenant Berard’s 2nd Platoon from the village of Ley. The panzers traveled along a shallow valley in an attempt to infiltrate through the 2nd Platoon’s tank outposts from the south. They failed.

When Sergeant Dunn was interviewed, the NCO described 2nd Platoon’s response to the German incursion: “All five tanks opened up and knocked out three of the Germans; the fourth [panzer] retreated behind the wreck of an American bomber. The second platoon put HE [High Explosive] on the plane and set it on fire. The tank was not observed to escape…. A fifth German tank was hit when observed coming out of Ley and destroyed.”

Berard’s platoon did not suffer a single casualty in the exchange. The only damage he sustained was to his own tank. A single round from one of the panzers had knocked off two bogey wheels from his track. That was it. But the Germans were drawing blood farther south.

Heading Off the German Advance

Colonel von Seckendorff still had another battalion to throw into the fray. The 2113th Panzer Battalion had over 40 Panzer IVs. Seckendorff directed the battalion to strike the American lines southwest of Bezange, near the town of Rechicourt. Unknown to the German colonel, the Americans had few forces with which to stop him. If his panzers flanked Abrams’ one tank company in Lezey, they would be able to overrun the headquarters of Combat Command A around the town of Arracourt, less than two kilometers west of Rechicourt.

A little after 7 am, Captain William A. Dwight, the liaison officer between CCA and the 37th Tank Battalion, was driving his jeep between the two command posts when he spotted a rumbling column of panzers as they approached from the town of Moncourt. He immediately returned to CCA headquarters to report what he saw. When Colonel Clarke heard the news, he realized how perilous his situation was, and he marched down to where Charlie Company, 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion had established its staging area. With him was Captain William A. Dwight.

Captain Thomas J. Evans, commander of Charlie Company, remembered that fateful morning when Clarke arrived at his tank destroyer. “I was shaving, beside a tank, when a shell came right down between the tank that I was standing near and another. It plowed up the ground. That’s when Colonel Clarke came over and said to move into position for the attack.”

At that moment, Evans only had one platoon that he could immediately dispatch. He grabbed the 3rd Platoon leader, 1st Lt. Edwin T. Leiper, and told him to go with Captain Dwight and Colonel Clarke. Leiper then rounded up his four tank destroyers, M18 Hellcats, and rolled out toward Rechicourt. Leiper and Dwight were leading the column in their own jeeps. It had started to drizzle, and no one could see anything through the rain and fog.

Without warning, explosions rocked the convoy. Dwight stopped his jeep and ran over to Leiper, asking him if the detonations were the result of direct fire or artillery. Leiper thought they were likely from direct fire weapons, but because of the poor visibility neither of the officers could tell what direction the rounds were coming from. While they debated, an American jeep raced past them from the direction of Bezange.

M18 Hellcats vs Mk IV Panzers

Dwight ordered Leiper to move his platoon to the northeast and occupy a position atop Hill 279. Leiper hopped back into his jeep and waved his hand forward, signaling his four tank destroyers to roll out. The platoon leader then drove his jeep up a trail and swung east cross country toward Hill 279, unassuming high ground with trees along its slopes.

Before his jeep reached the hill, Leiper, according to an interview, “was startled to see the muzzle of a German tank gun sticking out through the trees at what seemed to be less than thirty feet away. He immediately gave the dispersal signal and the many months of continuous practice proved its worthiness as the platoon promptly deployed with perfect accord. The lead tank destroyer, commanded by Sergeant [Emilio] Staci, had evidently seen the German tank at the same time as Lieutenant Leiper and opened fire immediately. Its first round scored a direct hit, exploding the German tank. The flames of the burning tank revealed others behind it in a V-formation, and Sergeant Staci’s next round hit a second German tank….”

Unfortunately, another Mk IV Panzer leveled its gun on Staci’s tank destroyer and blasted it. The Hellcat rocked backward from the hit as the armor-piercing round penetrated the gun shield. The resulting shrapnel ricocheted inside the turret, killing the assistant driver, Private Richard Graham, and injuring most of the crew. In retaliation, Sergeant Pat Ferraro’s tank destroyer knocked out the panzer that had shot at Staci’s Hellcat, avenging Graham’s death.

The fight continued. The crew of a fourth panzer saw that the tank destroyers now outnumbered them and began to back up. It was to no avail. The surviving Hellcat crews refused to allow them to leave, aiming their 76mm guns at the retreating panzer. Within seconds, it was a smoldering wreck. A fifth panzer then appeared, but it, too, fell victim to 3rd Platoon. According to the lieutenant, the short engagement lasted only a few minutes, but the Hellcat platoon had emerged victorious.

For the next hour, the two sides continued their game of cat and mouse in the lingering mist and rain. Leiper could not see the panzers, but he could hear them east of his location. By now, the mid-September sun was burning off the fog, and it only remained in the valleys. After a fruitless search for the noisy panzers, Leiper returned to his tank destroyers still on the hill northeast of Rechicourt.

Around midmorning, Leiper and his men spotted some armored vehicles and infantry moving along the ridgeline that ran from the eastern edge of Rechicourt to Bezange opposite their location. At first Leiper and Dwight thought the tanks were tank destroyers from the other Charlie Company platoons. The appearance of a fifth and sixth tank quickly dissuaded them of that notion, as Hellcat platoons had only four tank destroyers. Someone probably grabbed some binoculars and discerned that the tanks were in fact more Mk IV panzers from the 2113th Panzer Battalion, not a friendly column of Allied tanks.

With the enemy sighted, the crews swiftly brought their 76mm guns onto the targets. Once again, the Americans were able to get the drop on the Germans, firing first. The crack of the 76mm guns echoed across the valley. Less than a second later, one of the panzers shuddered as the armor-piercing round from one of the Hellcats ripped through its steel hull. Seconds later, another panzer brewed up. Before it was over, four or five were ablaze, and not a single Hellcat had been damaged in return. Leiper’s luck, though, would not last forever.

Leiper Withdraws His Hellcats

A few minutes earlier, Captain Dwight had requested artillery support for his position on the hill northeast of Rechicourt. Within minutes, an artillery spotter plane arrived over the battlefield to coordinate fire. For the panzergrenadiers, the incoming artillery was deadly, and after several devastating barrages the harried infantry scattered and disappeared. Then the aerial forward observer spotted three more panzers trying to flank 3rd Platoon and attack it from the rear. To alert Leiper’s platoon, the pilot dove the plane and fired several rockets at the creeping tanks to mark their positions.

When Leiper saw the three panzers, he ordered Sergeant Steve Krewsky’s tank destroyer to swing around and open fire. Krewsky’s crew responded. Within seconds, Corporal Floyd Eaton opened fire and had knocked out two of the panzers before the third returned fire. The third panzer’s round slammed into the Hellcat’s right sprocket. The wounded vehicle lurched from the blow, neutralized.

With two tank destroyers now out of action, Leiper decided it was time to pull back and lick his wounds. He ordered Sergeant Ferraro’s tank destroyer to move up and tow the other disabled Hellcat out of harm’s way. Ferraro then edged his armored vehicle forward. Meanwhile, the third panzer remained unscathed. When the panzer crew saw Ferraro’s M18 appear along the crest, it opened fire. As with Staci’s Hellcat, the 75mm armor-piercing round penetrated Ferraro’s gun shield, and the spall bounced around the turret like a pinball machine, wounding both Corporal Valentine Folk and Pfc. Henry Godwin.

Both Leiper and Dwight realized it was time to hunker down and wait for reinforcements. Sergeant Edwin McGurk, commanding Leiper’s last operating Hellcat, reversed his vehicle behind the ridge so that it was now in defilade. The surviving platoon members pulled the machine guns off the two stricken Hellcats, using them in a perimeter defense. Meanwhile, Captain Dwight kept CCA informed of their precarious situation with his jeep’s radio.

Throughout the rest of the morning and into the early afternoon, panzers emerged from the wood line bordering the village of Moncourt, east of their battle position, to probe for Americans in the valley. Each time, McGurk’s lone Hellcat would make them pay for their curiosity. In fact, Corporal Dominick Sorrentino, McGurk’s gunner, knocked out two more panzers with shots to their rear. The panzergrenadiers also tried their luck advancing from the wood line, but Leiper’s dismounted machine guns kept them at bay. Later that day, tanks from the 35th Tank Battalion relieved Leiper’s platoon. His tank destroyers had singlehandedly destroyed at least 14 panzers.

“In Line Formation [With] All Guns a-Blazing”

Despite the success of the two Charlie Companies, the Germans refused to give up. Another column of 12 Panther tanks attempted to breach the cordon around CCA headquarters. Initially, Colonel Clarke only had artillery to stop them. Nevertheless, the cannon cockers pulled the lanyards on their howitzers and opened fire over direct sights. Clarke was anxious for any unit to reinforce his headquarters. The first to arrive was Captain Jimmie Leach and Baker Company, 37th Tank Battalion.

In an interview for a television documentary, Leach recalled his meeting with Colonel Clarke. “Now, when I arrived at Clarke’s CP … I found Colonel Clarke, Colonel [Hal] Pattinson, and Major Pat Hyde in a ditch, and the German tanks were right up in front of them … about a dozen Panther tanks moving right across [from] them.”

According to the interview, Clarke then said to Leach, “You see those vehicles?”

“Yes sir,” Leach replied.

Pointing at the offending tanks, Clarke declared, “They’re German. I want you to get rid of them.”

Leach then rallied his platoons as they arrived on the battlefield. Once he had two platoons ready, he gathered his tank commanders and showed them the location of the nearby Panthers. Leach then instructed them: “Mount tanks now. I want you to move guns a-blazing—In line formation [with] all guns a-blazing.”

Leach’s company was under the direct control of Colonel Clarke and CCA for the time being. After receiving his marching orders from Captain Leach, 1st Lt. Merwin Marston, 3rd Platoon leader, took his Shermans down the Arracourt-Rechicourt road and divided his platoon into two sections. The first, under the command of Sergeant Morphew, rolled directly down the road, while Marston and the other section were north of the road, occupying a support position.

Forming Task Force Hunter

As they approached Rechicourt, both sections spotted the enemy. Marston spotted two panzers, while Morphew spotted three more from the road. Their training kicked in, and both sections opened fire as instructed, forcing the panzers to back into a patch of woods north of Rechicourt. Marston then ordered his gunners to keep firing to suppress the German panzers and prevent them from returning fire. At first, his plan did not work.

Leach described what happened. “Then the enemy got the range. One round dropped just short of Marston’s tanks. The next three hit all three tanks. Only Marston’s tank was penetrated, his gunner killed and his loader wounded. The other tanks were hit high, one [on] the turret, the other on the cupola. The latter was repaired and used again later the same day.”

By now, Marston had called for help. Within minutes, 2nd Platoon, under the command of Staff Sergeant James N. Barese, had passed by 3rd Platoon, moving into a blocking position south of the Arracourt-Rechicourt road. As ordered, Barese’s tankers were firing like mad. Then, according to Leach, “They [the Panthers] abandoned the battlefield. They put those things in high gear, those Panther tanks, and they took off over a hill, and disappeared beyond a big hill on the right.”

For several hours, the two platoons maintained these positions until Major William L. Hunter, the 37th Tank Battalion’s executive officer, arrived with the rest of B Company and two platoons from Able Company, 37th Tank Battalion. Together, these two companies formed a makeshift unit known as Task Force Hunter with the mission to blunt another German column approaching from the south.

Advancing Under Smoke

At 3 pm, Task Force Hunter received orders to reinforce Captain Lamison’s tank destroyers west of Bezange. When it arrived, one of the A Company tankers saw a panzer atop Hill 297, south of his location. One of the platoon leaders engaged the single panzer, which replied in kind, but neither side drew blood. Still, the panzer sighting was enough for Captain Leach and Captain William L. Spencer, the Able Company commander.

Spencer turned to Major Hunter, “We’re not doing any good right here. Why don’t we go look for these bastards? Maybe we can find them.” Hunter agreed, and all of them proceeded on foot toward Rechicourt, where they believed the rest of the panzers were hiding.

When they neared Rechicourt, they found four panzers laagering in a draw that was south and east of the village. The three officers planned a frontal attack with Able Company in front and Baker Company echeloned to the rear and south of Able. Spencer had only six tanks, but Leach had 14 M4s. Hunter wanted Spencer to fix the enemy with his smaller force, and then Leach would swing around and hit them in the flank with the larger company.

To conceal the movement, Hunter coordinated with the 94th Armored Field Artillery Battalion to blanket the area with smoke. Spencer then moved out with his company, comprised of only two understrength platoons. He placed 1st Platoon, under the command of Lieutenant Turner, on his northern flank and 2nd Platoon, under the command of Lieutenant C.L. De Craene, along his southern flank. Captain Spencer was in his tank between the two platoons.

“By the Left Flank, Gun’s Ablazing, Let’s Move”

Turner’s platoon stumbled upon the enemy first. Unfortunately, Leach and Spencer had not seen all the panzers. In fact, nine Panthers were in the immediate area, and Turner’s platoon hit them on the eastern flank. Turner’s three tanks halted along a ridge and then opened fire at a range of 250 meters.

According to Captain Leach, most of the Panther crews had dismounted and were “eating supper.” The sudden maelstrom of fire surprised them, and the panzer crews scurried back to their vehicles. Able Company struck them head on, which meant that the American gunners would have to penetrate the thickest portion of the panzers’ armor. Almost immediately, Captain Spencer’s tank shook and then rolled to a stop. One of the panzer gunners had scored a hit on Spencer’s tank. Then another panzer slew Turner’s tank, killing one of his crew. That left only two tanks from his platoon.

It got worse. Another 75mm round rattled De Craene’s tank, knocking the M4’s .50-caliber machine gun from the turret. The concussion also stunned De Craene for several moments. When he recovered, he ordered his driver to jam on the throttle, and his Sherman rumbled toward the line of panzers. Reacting to this charging metal rhinoceros, the German gunners peppered De Craene’s tank with multiple hits, killing him and most of his crew. Able Company was now in serious trouble. Spencer and De Craene had the only 76mm long-barreled Sherman guns in the company. All the other tankers in the company still were armed with the stubby 75s. Fortunately, help was on the way.

While Spencer’s company kept the Germans occupied, Leach’s company crept along a side road and passed the Panthers. The hedges and ridges lining the road prevented the Panther crews from detecting B Company until it was too late. When Leach’s last tank cleared the edge of the German line, he ordered, “By the left flank, gun’s ablazing, let’s move.”

The sudden attack to their flank stunned the German tankers. Barese’s platoon was the first to make contact. Leach’s company rolled down the hill, his tanks only stopping to fire. One by one, the Panthers brewed up until all nine were in flames. Leach’s company had also cleared out all the panzergrenadiers in the area around Moncourt, and both companies killed over 100 dismounted Germans. It was a total American victory.

Southwest of Task Force Hunter, Hellcats from 1st Platoon, Charlie Company, also joined the battle. Like their brethren in 3rd Platoon, the four Hellcats were scoring hits. Sergeant Henry Hartman’s crew accounted for the immobilization of five panzers, while Sergeant Tom Donovan’s team destroyed another three tanks. By nightfall, the initial German assault had ended.

Complete Disaster For the German Panzers

For the American forces, the final tally was staggering. The tank destroyers alone were credited with knocking out 19 panzers, while losing only three Hellcats. That was not all. Colonel Abrams claimed his battalion destroyed another 29 enemy tanks. His crews killed more than 200 enemy soldiers while losing only three tanks in return. For the Germans, this meant that the 113th Panzer Brigade had lost most of its panzers. The German assault had resulted in a complete disaster.

Though the Battle of Arracourt would last several more days, the Germans had squandered their best chance to inflict severe losses on the American forces on September 19. The 113th Panzer Brigade had overwhelming superiority in tanks and men. Despite this fact, it was still unable to defeat Abrams’ 37th Tank Battalion and Evans’ C Company, 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

The chief reason for the German defeat was their lack of reconnaissance, which prevented them from discovering the American battle positions before it was too late. As a consequence, the panzer companies rolled through the French countryside like blind men. Though the American tankers were outgunned in their Sherman tanks, they knew the ground and were far better trained. The result was a tactical American victory.

Training, indeed, seemed to play a large part in the U.S.’s victory. Knowing how to arrange their tanks and TDs against more powerful Panthers (and the lesser but still dangerous Mk. IVs) and, quickly formulating a strategy of how to first meet the tanks, and then go on the offensive, proved critical in the GI’s vastly successful battle against the vaunted German armor. Communications definitely helped, no doubt. The one technological advantage which proved its worth was the M4’s superior turret rotation mechanism, enabling them to rotate quicker against the panzers for aiming and firing. This action must have not only shown that the German armor was not absolutely invulnerable, but had to give the U.S. tankers needed morale to enable them to engage the panzers aggressively later on, provided that they had time to develop tactics to deal with the often individual disadvantages of facing them one on one.

I had not read about this armored engagement before now, and was surprisingly pleased to find out how successful our tankers were. Not only outnumbering the panzers but using superior tactics proved the way to defeat them in the drive across Western Europe.

The thing that should be realized is that the US had a different doctrine than the Germans when it came to tactics and how to use the armor they were equipped with. US doctrine was to use Tank Destroyer units against German Armor whenever possible and to use smoke and speed against German armor when fighting with Shermans. The Sherman was a very reliable tank that was mass produced and got the job done. The US had very good radios and could always call in artillery and air to take care of large armor units. The article proves that it is much easier to fight armor when defending. Most of the stories of German tanks taking out Sherman tanks are when the Germans are defending and catch Sherman tanks by surprise. US did build a superior tank to German armor but they entered the war too late and were used like Tank Destroyers. Were the German tanks better than the Sherman? Yes of course, but they weren’t enough to stop the offense which was mostly conducted by Infantry with all the other branches supporting them. The Sherman was good enough for US, and all of their Allies. In the Pacific Theater the Sherman was very effective.

LTC Weide Retired

We were on the right track with the WP rounds, but we probably should have developed something like a napalm round, to strike the outer surface of any target, and stick to it, and start an intense fire, which could not be extinguished, and just burn them up.

If our 75mm shells just bounced off the front armor of the Panthers, which they did, we needed something more effective, and smarter ammo would have been just the ticket, since we couldn’t install bigger guns in our M4s overnight.

The thing that surprises me is that we didn’t concentrate enough on just disabling the German tanks, when we knew our 75mm gun wouldn’t penetrate the front plates.

If we had used WP rounds, and hit their undercarriage, we could have stopped them in their tracks, and had an immobilized target to shoot at, with anything we had available.

In fact, it would have simply burned up, sitting there immobile.

Thank you for the clear description of the fighting, without bogging down us amateurs with myriad details. Good article.

T. Fowler