By John Walker

On March 5, 1851, a group of Mexican soldiers from Sonora plundered a lightly guarded Apache camp outside the village of Janos in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua 75 miles south of the U.S.-Mexican border. Janos was a well-known location at which the Mexican locals traded with the Apaches. In the process, the Mexicans slaughtered 21 Apache women and children at the camp.

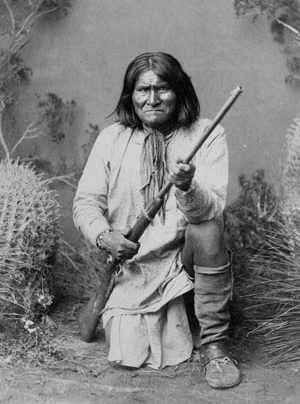

The next morning, a Chiricahua Apache named Goyahkla, meaning “one who yawns,” returned to the camp and found the corpses of his aged mother, wife, and three children, all scalped and lying in pools of blood. From that moment forward, vengeance against Mexicans, innocent or guilty, became Goyahkla’s driving passion. He participated in countless raids in northern Mexico for more than three decades afterward. The more familiar English name by which Goyahkla became known, Geronimo, is believed to be based on the Mexicans’ appeal to Saint Jerome for succor. In their terror, the Mexicans cried out, “Jeronimo!”

Geronimo was a skilled and battle-hardened fighter who possessed superb knowledge of the terrain both in northwestern Mexico and the southern portion of the New Mexico Territory to the north. Geronimo’s unyielding pursuit of armed resistance in the face of overwhelming odds confounded not only his Mexican and American adversaries, but also many of his fellow Apaches.

To his supporters, Geronimo was the embodiment of proud resistance and the defender of the old Chiricahua way of life, while to many whites he was the perpetrator of unspeakable, savage cruelties. Geronimo thought nothing of torturing Mexican soldiers to death and committed atrocities against noncombatants on both sides of the border.

Beginning in the 1870s, when the Apaches were forcibly relocated to reservations far from their tribal homelands, many Apaches concluded that the white man’s path was their only viable road to peace and survival. For that reason, they regarded Geronimo as a stubborn troublemaker who had become unhinged by his seemingly unquenchable thirst for revenge. They firmly believed that his actions would bring down the enemy’s wrath on his own people.

Loss of Land in the Mexican-American War

Geronimo was born into the Bedonkohe band of the Chiricahua Apache in 1829 near the headwaters of the Gila River in Mexico. His father was Taklishim, “the gray one,” and his mother was Juana. The Bedonkohe band, along with the Chokohen, Nedhni, and Chihenne, constituted the four bands of the Chiricahua.

There was no Apache nation, but several tribes scattered across the southwest region of the modern-day United States. The Apaches are believed to have settled in the southern and southwestern parts of modern-day Arizona and New Mexico, respectively, and the northwestern region of Mexico arounf 1,500 bc after migrating southward along the face of the Rocky Mountains, following the great buffalo herds. The Spanish called this area Apacheria.

The Apaches were confronted by the fierce and more numerous Comanches, an aggressive tribe that was expanding into the western Great Plains. The Comanches forced the Apache further westward into the mountain ranges west of the plains.

When Francisco Vasquez de Coronado encountered them in northern New Spain in 1541, he described the Apache as “proud, fierce, and independent, but gentle if left alone.” Their mobility and knowledge of the terrain was unrivalled and became the key to their survival. The Apaches adapted and thrived in the harsh terrain in which they lived. The Apaches moved to the lower valleys to hunt during the winter. Although they were nomads, they grew beans, corn, and melons on small tracts.

Even though he was a grandson of the revered Bedonkohe chief Mahco, Geronimo’s bloodline did not secure him a position as a chief. Like other youths of his band, his entire boyhood was a long and arduous apprenticeship. He learned hunting, horsemanship, and warfare skills from experienced warriors. Although Geronimo was not a hereditary chief, his reputation grew to great heights among Chiricahua because of his skill and the bravery he exhibited in countless actions against the Mexicans and Americans. The Apaches eventually came to regard him as a shaman.

After the U.S.-Mexican War ended in 1848, the subsequent influx of Anglo-American miners, ranchers, settlers, and soldiers into Apacheria disrupted Chiricahuan ways of life that had been in place for almost three centuries and made conflict inevitable. Geronimo bitterly rejected the notion that Mexico had the right to cede his people’s homelands to the victorious Americans.

The Gadsden Purchase

The Gadsden Purchase of 1854 had a direct influence on Apache life. Through the treaty, the United States paid Mexico $10 million for approximately 30,000 square miles of Mexico south of the Gila River. The treaty furnished the land needed for the southern transcontinental railroad. The affected area lay in the heart of Apacheria.

The two greatest Chiricahua chiefs, Mangas Coloradas of the Mimbreno band of the Central Apaches and Cochise of the Chokohen band of the Chiricahua, initially held no animosity toward the American newcomers. They actually preferred the Americans to the Mexicans. Mangas Coloradas informed American scout Kit Carson in 1846 that he was willing to join the Americans in the war against their common enemy, which was the Republic of Mexico. In later years, the two prominent chiefs would attempt to reach accommodations with the Americans that would put an end to hostilities between their two peoples and allow the Apaches to continue raiding into northern Mexico with impunity.

Initially, the Apache refrained from raiding American property. The Apaches had attacked the town of Tubac, Arizona, throughout the early 1840s when it was held by the Sonoran Mexicans, but when an American exploring and mining company was established at Tubac the following decade, the Apaches left it alone. Apache raiders also left unmolested the Americans residing at Fort Buchanan near Tucson. The post, which was a collection of adobe houses without an enclosed stockade, was abandoned in 1861 when U.S. forces stationed there fell back to New Mexico.

The Apache chiefs and their warriors “were men of noticeable brain power, physically perfect and mentally acute—just the individuals to lead a forlorn hope in the face of every obstacle,” wrote Lieutenant John Bourke, a U.S. Army cavalry officer.

The Apache Wars

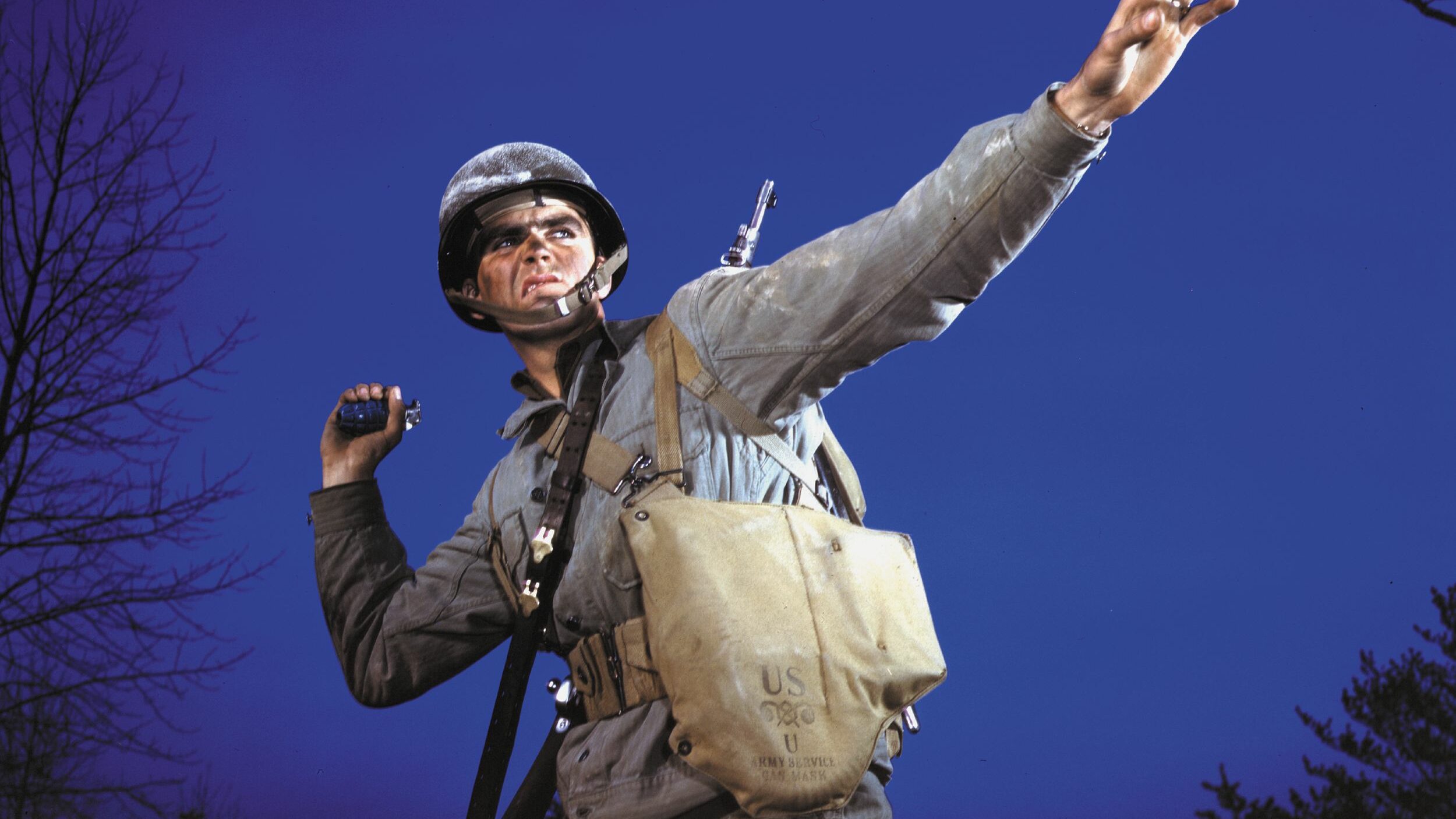

The Bascom Affair, an incident in 1861 between the Apaches and a U.S. force under Lieutenant George Nicholas Bascom, destroyed the tenuous standoff that had developed between the whites and Chiricahuas. The incident, in which an inexperienced junior officer was given the authority to act in any way he saw fit, was the spark that ignited 35 years of raids and reprisals between the Americans and Chiricahuas in what became known as the Apache Wars.

After Cochise of the Chokohen band was falsely accused of being involved in the theft of a rancher’s livestock and the kidnapping of his mixed-blood stepson, Bascom arrested Cochise and several of his family members. Cochise escaped, but his family members did not. Cochise joined forces with Geronimo, Mangas Coloradas, and various members of the White Mountain and Chihenne Apaches in raiding the Butterfield Stage Line and other targets.

Bascom retaliated by executing six Apache men, including Cochise’s brother, which drove Cochise to seek revenge. After this trouble, all the Indians agreed not to be friendly with the white men anymore.

In January 1863, Brig Gen. Joseph West, commander of the Department of New Mexico’s southern region, invited Mangas Coloradas to peace negotiations at Pinos Altos. When the chief arrived, the soldiers killed him and mutilated his body. The act was “the greatest of wrongs,” said Geronimo.

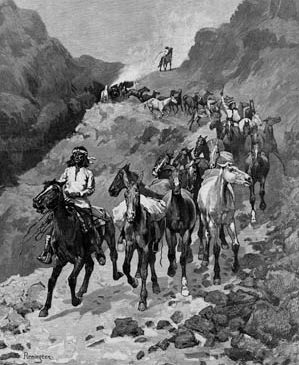

The Apache raids continued unabated. Geronimo often rode on the raids with Juh, his longtime friend, ally, and cousin by marriage. When Geronimo and Juh needed sanctuary, they crossed into northern Mexico and camped in the Sierra Madre Mountains.

The Apaches were able to obtain rifles by ambushing soldiers, miners, or ranchers or through illicit trading with Americans. They also picked up rifles and ammunition after skirmishes and battles. The Apaches occasionally were able to capture U.S. Army pack mules laden with reserve ammunition packs intended for U.S. cavalry detachments operating in Apacheria. Geronimo was a superb marksman, and he is known to have preferred the Springfield 1873 “Trapdoor” rifle and the Winchester 1876 rifle.

A key incident occurred in April 1871 at Camp Grant north of Tucson when Aravaipa Apache Chief Eskiminzin’s warriors arrived and surrendered their weapons. A vigilante force of fearful Tucson residents, believing raiders were present, attacked the camp and killed more than 150 noncombatants, most of whom were women and children. U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant was so enraged that he sent a peace delegation to the Arizona Territory, after which a reservation system was established for the Apache with four agencies in Arizona and one in New Mexico.

“Hell’s Forty Acres”

By the 1870s, American occupation of their territory had forced the Chiricahua to accept the hard lesson that some degree of accommodation with the newcomers was necessary for their survival. Hoping their children might enjoy the benefits of peace while retaining their traditional ways of life, the Chiricahuas agreed to settle on two reservations located in their tribal homelands.

After 12 years of hostilities, Cochise signed a peace treaty in October 1872 with Brig. Gen. Oliver O. Howard that established the short-lived “Chiricahua,” or “Apache Pass” reservation. The reservation included Sulphur Springs Valley, the Dragoon Mountains, and the San Pedro Valley of the southeastern Arizona Territory. Seven hundred Chokonen, Nehnhi, and Bedokohe settled on the Chiricahua reservation, while another 544 Chiricahuas settled at the Tularosa reservation in the New Mexico Territory.

The population of the four Chiricahua bands, which had steadily declined between 1850 and 1870 from a high of between 2,000 and 2,500, had dwindled by that time to 1,244 men, women, and children. In the immediate aftermath of the establishment of the reservations, the Chiricahuas hunted and gathered peacefully off the reservation as specified in the 1872 peace treaty.

The U.S. government adhered to Howard’s peace treaty for only four years. In 1876, the U.S. government reneged on its agreements and announced that all Chiricahuas would be relocated to the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation. Unlike the Chiricahua reservation, the San Carlos reservation consisted of barren land where the Apache were confined under deplorable living conditions. Apache and whites alike called it “Hell’s Forty Acres.”

This action, which opened Chiricahua homelands to white settlement and mining, sparked a new round of hostilities. “It was an outrageous proceeding, one for which I would still have blushed if I hadn’t got over blushing for anything the U.S. government did in Indian matters,” said U.S. Army Lieutenant John Bourke of the forced removal to the San Carlos reservation in 1876.

Geronimo’s Resistance

Anxious for peace at almost any cost, about a third of the Chiricahuas agreed to move to the San Carlos reservation under military escort. The other two thirds, who preferred the uncertain life in the Sierra Madre Mountains of northern Mexico to that on the reservation, resumed their raiding ways. Geronimo led approximately 400 Chiricahuas into Mexico. The U.S. government branded them hostiles. “His only redeeming traits were courage and determination,” U.S. Cavalry Lieutenant Britton Davis said of Geronimo. “His word, no matter how earnestly pledged, was worthless.”

After John Philip Clum, the Indian Agent for the San Carlos Apache Indian reservation, captured Geronimo and a group of his followers through deceit in 1877, Geronimo was taken in chains to the San Carlos reservation for the first time.

Geronimo and other Chiricahuas did not get along well with Apaches of other tribes. After he was released months later, Geronimo and Chief Victorio of the Warm Springs band of the Tchihendehs, who led the Warm Springs subgroup of the Chihenne band, became the two foremost warriors leading Indian resistance to reservation life. Victorio led his followers in a war lasting from 1877 until 1879. Geronimo’s final resistance took place from 1881 until 1886.

In October 1880, Victorio was slain by Mexican troops, and Geronimo offered to lead a war party back to San Carlos to free his Warm Springs followers there, which by then were led by Loco, a chief of the Mibreno band. His motivation was to free as many warriors as possible, which would give him more manpower to kill Mexicans; the women and children were just a corollary. When some of Loco’s people hesitated to flee, Geronimo raised his rifle and proclaimed, “Take them all. No one is to be left in the camp. Shoot down anyone who refuses to go with us.”

Loco despised Geronimo, and he blamed him for the subsequent sufferings of his people. Loco and many of his followers would later claim that Geronimo had not rescued them, but rather kidnapped them.

“Victorio had never approved of the ways of Geronimo,” Victorio’s daughter said. “His way of warfare cost the lives of too many of the younger, less experienced warriors. He fought for his own glory, not for the welfare of the Indeh.”

Valuing Warriors Over Noncombatants

Not long after this group, which included Geronimo, Loco, and other prominent Apache warriors, reached sanctuary in the mountains on northern Mexico, they were ambushed by Mexican regulars and militia at Aliso Creek, a battle that exemplified not only Geronimo’s skill in warfare but his utter ruthlessness as well.

After the Mexicans set a fire to smoke out the Chiricahuas, Naiche led 15 warriors in the vanguard while Geronimo and 30 warriors fought a rearguard action, with the women and children in the center. In heavy fighting, Geronimo and his men killed a large number of the attackers, forcing the survivors to fall back. Geronimo decided to use the smoke as a screen for an escape, and instructed the women to strangle the remaining infants so their cries would not give away their position. If they refused, he declared, he would leave them all to their fates. Geronimo had abandoned women and children three times before. He believed saving his warriors took precedence over the fate of the noncombatants.

Geronimo’s cousin Fun rejected such talk. He told Geronimo that he would shoot him if he repeated it. Geronimo then vanished into the mountains. The warriors who remained behind and the women and children managed to escape. The Chiricahuas were able to regroup in the mountains that night. Altogether, they had lost 78 killed, most of whom were from Loco’s band, and 33 women captured, including Loco’s daughter. Most of the Chihenne blamed Geronimo for the catastrophe. They held that Geronimo had forced them at gunpoint to abandon the safety of the San Carlos reservation. “I am without friends, for my people have turned on me,” said Geronimo.

Geronimo and Mangas (the son of Mangas Coloradas) participated in the final breakout from San Carlos in May 1885 that hastened the end of Geronimo’s resistance. Only one-fourth of the Chiricahuas present on the agency, 34 men and 110 women and children, consented to leave. During the next 16 months the Chiricahuas raided on both sides of the border. In their wake they left dozens of dead, killed large numbers of livestock, and destroyed considerable property.

“I Should Never Have Surrendered”

In 1882, Brig. Gen. George Crook, who had campaigned against other Apache, was sent to the Arizona Territory to quell the Apache threat. Crook issued a call for Apache scouts to help find the renegades. As many as 80 Chiricahua men answered the call. The following year, Crook led an expedition into the Sierra Madre Mountains of northern Mexico. During the expedition, Crook and his subordinates—Captain Emmet Crawford and Lieutenant Charles Gatewood—convinced Geronimo to return to the reservation, albeit only for a short time.

Three years later, Brig. Gen. Nelson Miles took command of U.S. troops in the Arizona Territory. He led 5,000 soldiers, one-fourth of the standing forces of the U.S. Army, in pursuit of Geronimo and his small band.

Captain Henry Lawton and his troops, who were based at Fort Huachuca in the Arizona Territory, doggedly tracked Geronimo and his exhausted fugitives through the desolate landscape. They finally convinced the Chiricahua war leader to surrender for the last time in September 1886. Although U.S. soldiers would face occasional problems with Apaches, Geronimo’s surrender ended a struggle by the Chiricahua to hold on to their homeland that lasted more than two centuries.

Four days after meeting with Miles, Geronimo and his 27 survivors were on a train to Florida as prisoners of war. Upon their arrival in Florida, they joined 400 other surviving Chiricahuas. These were the Chiricahuas who had remained at San Carlos, including the loyal scouts, who already had been sent to Florida by U.S. President Grover Cleveland.

The Chiricahua endured a 27-year odyssey as prisoners before being freed in 1913. That odyssey took them from Florida to Alabama and then to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. At Fort Sill, they built villages around the post and farmed the land. Geronimo died in 1909 after having spent 14 years at the fort.

By 1913 only 269 Chiricahua remained. Most of those had been born in captivity. They were not allowed to return to Arizona, although the U.S. government offered them space on the Mescalero Apache reservation in southern New Mexico. Two-thirds of them opted to move, and the other third stayed in Oklahoma.

In these two locations, the Chiricahua live today, among them a few direct descendants of Geronimo and Cochise. “I should never have surrendered,” said Geronimo on his deathbed. “I should have fought until I was the last man to survive.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments