By Eric Niderost

Weather has long played a vital role in human history. Kublai Khan’s attempted conquest of Japan was foiled when his invasion fleet was destroyed by a typhoon. Napoleon’s Grand Armee perished during his ill-fated Russian campaign, laid low by the sweltering heat of summer and the frigid cold of winter. Even at Waterloo, torrential rains turned the battlefield into a quagmire and contributed to his final defeat.

But the weather became even more important during the 20th century thanks to the invention of the airplane, tank, and modern ship. Bombers and other aircraft might be grounded by bad weather or their targets obscured by fog or clouds. Land offensives also depended on accurate predictions of the weather, and at sea convoys bearing vital supplies needed reliable forecasts to deliver their cargoes. (You can learn more about the events and circumstances that shaped the Second Great War inside WWII History magazine.)

Meteorologists of the 1940s lacked such modern devices as satellite imagery, depending instead on barometers and other traditional, time-honored tools. Even so, weathermen could make fairly accurate predictions up to 72 hours in advance.

When the war began in 1939, the Germans found themselves at a disadvantage when it came to gathering and interpreting weather data. European weather forms in the Arctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere, finally drifting west to east. Germany had no colonies in the region that it could use as reporting stations.

Greenland, Jan Mayen Island, and the Svelbard Archipelago were examples of prime weather-reporting locations, but they were owned by then-neutral Denmark and Norway. In the early months of the war, Scandinavia’s neutrality actually helped the Germans. In Greenland, for example, the island’s weather stations regularly transmitted information in plain international code. The meteorologists on Norway’s Jan Mayen Island did the same.

But that all changed when Hitler invaded Denmark and Norway on April 9, 1940. When their home countries were occupied, the island colonies were forced to fend for themselves. Most chose resistance—even if passive—as a better option than collaboration with the Nazis. The German conquest of their homelands meant that most Danes and Norwegians overseas began to cooperate with the British and Americans.

U-Boats and the Wekusta

By the summer of 1940, the Germans found themselves on the horns of a dilemma. They had triumphed in Scandinavia, but that very success jeopardized future operations. Appalled at the brutal subjugation of their countries, Danish and Norwegian weathermen overseas now gave their information to the Allies. Casting about for a solution to an ever growing problem, the Germans turned to Admiral Karl Dönitz and his submarines. Two German U-boats were assigned full-time duties as weather-reporting stations from August 1940 to January 1941.

Dönitz himself chafed at these tasks, believing that gathering meteorological data, however crucial, was secondary to sinking enemy ships. The commitment seemed small on paper, but due to turnovers, transits, and refits six submarines were actually part of the program. Dönitz began the war with 57 submarines, and only 27 were oceangoing, long-range Type VIIs. Originally, plans called for 300 U-boats to prowl the Atlantic, but the war came too soon for these projections to become reality. The admiral hated the idea of his precious U-boats being used in such a “pedestrian” manner.

German U-boats finally ended their full-time commitment in January 1941, much to Dönitz’s relief. However, they still occasionally gathered weather data while on other missions. As time went on, U-boats also ferried weather personnel to and from weather station sites, transported equipment, and carried base supplies.

The German Luftwaffe also conducted weather reconnaissance patrols that ranged as far as Greenland. Wetterkundungsstaffel 5 (Weather Squadron 5), operating out of Trondheim and Banak, Norway, made regular twice-daily flights across the frigid Arctic seas. The squadron used specially configured Heinkel He-111s, Junkers Ju-88s and Ju-52s, and Dornier Do-17s, all sporting the squadron’s distinctive “flying frog” emblem as nose art.

Weather Squadron 5 had to deal with Arctic conditions, including temperature extremes, icing, and engine problems. Allied antiaircraft defenses at Spitsbergen and elsewhere also took a toll, as did Allied fighters. But in the end, weather gathering by air was too unreliable. Ironically, missions were often cancelled because aircraft were grounded due to bad weather.

The Weather Trawler Program

The Germans decided to send weather ships, “fishing” trawlers presumably able to escape Allied detection while at the same time supplying vital meteorological data, into North Atlantic waters. The weather trawler program was not merely a failure but an unmitigated disaster. In fact, a case can be made that it was one of the major contributors to Germany’s defeat.

Unfortunately for the Nazis, the British were monitoring weather ship transmissions to such an extent the element of surprise was lost. One by one the weather trawlers were captured or sunk, relentlessly pursued by the British Royal Navy. The Royal Navy expended much time, effort, and matériel taking these weather ships, but not just because they were transmitting meteorological data. The weather trawlers carried Enigma cypher machines, devices that transmitted and received messages in the secret German Enigma code.

Each captured weather trawler provided cryptographic items, rotors and the like, that helped the British crack the Enigma code. The Germans never fully understood that their weather missions compromised Enigma, but they did finally come to realize that the trawlers were too vulnerable to enemy action. It became more and more clear that only land-based stations could provide the accurate weather data needed to form useful predictions.

British Evacuation From Jan Mayen Island

On the debit side, all possible sites were in Allied or anti-Nazi hands in 1940, making the German task that much more difficult. But these possible weather station sites were also very remote, desolate areas infamous for their cold temperature extremes and natural hazards. Humans had to deal with such dangers as polar bear attacks. In such isolated areas, it might just be possible to establish bases that would escape detection.

Poring over a map, it was clear Jan Mayen Island, Spitsbergen, and Greenland were among the best locations for gathering and sending weather data. All were in the Arctic regions where European weather fronts form, and all were remote enough to give the Germans at least a hope of success. In addition, weather stations were already in place. If the German Navy, the Kriegsmarine, acted swiftly, it might establish bases before the British could effect countermeasures.

Jan Mayen Island is a barren rock only 34 miles long, its most notable feature the snow covered, 7,470-foot Beerenberg volcano. Owned by Norway, it has no natural resources but is ideal for weather reporting. In 1940, Jan Mayen was inhabited by four Norwegian meteorologists who faithfully transmitted weather data to the homeland. They were shocked and appalled by the German invasion, which they heard over their radio.

The meteorologists immediately ceased transmitting to Norway and began sending reports to the British. They also requested British help because it was feared the Germans might attempt a physical occupation of the island. British authorities acted with alacrity, dispatching the free Norwegian gunboat Fridtjof Nansen with a crew of 68 men to help the meteorologists and garrison the island against the Germans.

The Fridtjof Nansen arrived in October 1940, only to run aground on one of Jan Mayen’s underwater reefs. The ship was a total loss, temporarily marooning the Norwegians with the weather station personnel they had come to support. Winter was coming on with its storms and near total darkness. In light of these changing circumstances, it was decided to temporarily abandon Jan Mayen to the elements.

The now stranded garrison radioed British authorities and then settled down to await rescue. The food situation was a problem, but luckily polar bears prowled the area in their constant search for seals. Two or three of the giant animals were shot and added to the larder. By the time the rescue ship appeared, the seas were rough with white-foamed water crashing against the island rocks. It took 10 trips to shuttle the stranded Norwegians to the rescue ship over treacherous water.

The four original meteorologists were the last to abandon the island, but before they departed they destroyed their radio equipment and anything else that might be of value to the Germans. The British intended to reoccupy Jan Mayen in the spring.

Sonderkommando “Graf Finkenstein”

The Germans soon noticed that the island had gone silent. There was no radio traffic coming from Jan Mayen. They dispatched reconnaissance aircraft from Norway, which confirmed that the island was uninhabited. The German Abwehr (intelligence service) took an immediate interest in the situation.

Conventional wisdom held that no one in his right mind would mount an expedition to Jan Mayen so close to the coming of winter, but if the Germans acted with dispatch they might land a team before the really bad weather and darkness set it. It was a risk, but a calculated one, and would reap rich rewards in weather data.

A weather troop was immediately formed called the Sonderkommando “Graf Finkenstein,” named after its aristocratic leader, Ulrich, Graf (Count) von Finkenstein. The expedition was an interservice one and slightly confusing in composition, overlapping authority, and duties, which was typical of the Nazis in this period. The teams would be transported by the fishing trawler Hinrich Freese, captained by Lieutenant Wilhelm Kracke and crewed by 13 civilian sailors.

The Hinrich Freese departed Trondheim, Norway, on November 12, 1940. Apart from the crew, there were three distinct units aboard. First, there was a Luftwaffe weather troop, three men under Lieutenant Harald Bruhn. Next, there were two “Abwehr-funker” Intelligence Service radiomen who transmitted weather reports back to Europe. Finally, there was the Sonderkommando “Graf Finkenstein,” a party consisting of the count, turncoat Dane Kurt Carlis Hansen, and three other men.

Unfortunately for the Germans, the British were taking no chances with Jan Mayen, which they codenamed Island X. The Royal Navy, determined that it must be kept out of German hands at all costs, kept a close eye on the island and its approaches. With stormy seas and the fast approach of winter, the patrols were tedious and often dangerous, but British perseverance was soon rewarded.

The Hinrich Freese arrived at Jan Mayen on November 16, 1940, without incident, but its luck was not to hold. The light cruiser HMS Naiad caught the German trawler before it could land its weather team and equipment. Hinrich Freese tried to run, and Naiad gave chase. There are two versions of what happened next. One says the German skipper tried to maneuver his ship though the treacherous rocks but failed in the attempt. Most accounts maintain the Germans deliberately wrecked the ship to avoid its imminent capture.

In any case, Hinrich Freese smashed into the lava rocks, the impact shuddering the vessel from stem to stern. The lifeboats were launched with great difficulty because the heavy surf kept pushing them against the sides of the sinking German trawler. Huge waves engulfed the lifeboats, swamping them and forcing the survivors into the frigid sea. Two drowned, but the rest—soggy, exhausted, and freezing—made it ashore, only to be picked up by a British landing party.

Air Raids on Jan Mayen

The Allies returned to Jan Mayen on March 10, 1941, when the free Norwegian ship Veslekari arrived with 12 Norwegian meteorologists. As time went on, a small garrison was added to the island’s population, together with some antiaircraft guns. The latter were needed because the Germans began conducting air raids on the weather station.

Jan Mayen Island is only about 600 miles west of Norway, easily within reach of long-range German bombers. Four-engine Focke-Wulf Fw-200 Condor bombers visited frequently for a time but inflicted little significant damage. This was no milk run for Luftwaffe air crews; the weather could turn bad, and Allied antiaircraft guns were a danger. On August 7, 1941, a Focke-Wulf 200 crashed on one of the island’s mountainsides, lost in heavy fog.

All nine crew members were killed, and pieces of wreckage remain to this day. In 1950, the wreckage of another German plane was found on the southwest side of the island. By the end of 1941, the Germans had given up any idea of taking the island, though nuisance bombing raids continued sporadically.

Operation Gauntlet

Spitsbergen was another area of interest for the Germans in their never-ending quest to establish weather stations. It is a large island, some 280 miles long and from 25 to 140 miles wide. Spitsbergen is part of the Svalbard Archipelago and is owned by Norway. It assumed an even greater importance after Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941.

Aside from its strategic location for weather gathering, Spitsbergen had valuable coal deposits. Some of the island’s coal mines were operated by Norwegian concerns while others were controlled by the Russians. Preliminary investigations ruled out Spitsbergen as an Allied naval base due to the hazards of seasonal ice.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was behind a plan that called for bold and decisive action. The island’s entire population would be evacuated, with the Russians repatriated to the Soviet Union and the Norwegians to Britain. Both Moscow and the Norwegian government in exile readily agreed to the scheme.

The mission, code-named Operation Gauntlet, sailed on August 19, 1941, arriving a few days later. The British effort included Canadian troops and the Royal Navy’s Force K under Rear Admiral Philip Vian. The troops were carried by the liner Empress of Canada, escorted by Vian’s flagship, the cruiser HMS Nigeria, the cruiser HMS Aurora, three destroyers, and several smaller support ships.

At the time it was not known whether the Germans had occupied the island. They had not, and the local Norwegian and Russian inhabitants were more than cooperative. The miners were evacuated, and demolition teams fanned out to destroy the mines and excess fuel stocks. While the demolition continued, radio stations on the island continued to broadcast as if all was well, even sending false weather reports of heavy fog to deter German reconnaissance aircraft. Only when the mission was completed were the radio stations destroyed.

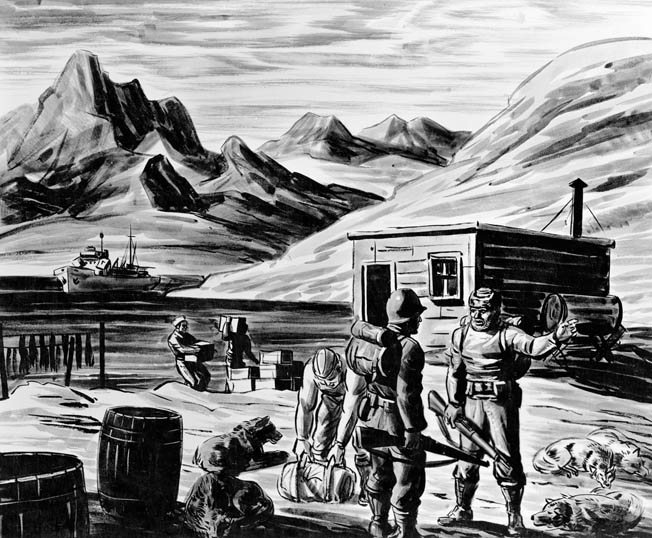

No fewer than 1,955 Russians and 765 Norwegians were evacuated from Spitsbergen. The operation was a success, but once again, as with Jan Mayen Island, the Germans attempted to exploit the vacuum that was created by an Allied withdrawal. It took them a few days to catch on, but once they realized what was happening they moved swiftly. A 10-man Luftwaffe meteorological team was landed on the northeast corner of the island and a landing strip carved out of the barren soil.

The German Weather Stations of Spitsbergen

Throughout October 1941, the Luftwaffe shuttled in nearly four tons of supplies. By November 11, several German weather stations were in full operation. Station Banso passed the winter of 1941-1942 in Adventdalen near Longyearbyen, and Station Knospe transmitted near Krossfjord.

The Allies were not going to let the Nazis seize control of the island without a fight, however. It was frustrating, but they did have to wait until the harsh Arctic winter had passed. For the next six months, the German weather stations were left unmolested.

In May 1942, the ships Isbjorn and Selis arrived at Spitsbergen carrying around 80 free Norwegian ski troops to root out the Germans and establish Allied control. The ships sailed up the Gronfjord (Green Fjord) successfully and anchored to unload supplies. On the night of May 14, they were attacked by Fw-200s and badly damaged. One of the ships sank, and the other was set ablaze.

Fourteen Norwegians were killed in the air raid, but the others successfully abandoned ship and managed to reach shore after plunging into subfreezing water and clambering onto nearby ice floes. According to a contemporary Time magazine account, they got to shore at Barentsburg, but their expedition was a shambles. Their radio was gone. They were encumbered by wounded and had only managed to salvage 15 skis, a few rifles, and a single broken lamp.

Luckily they managed to flag down a Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat from the British Coastal Command by using their salvaged lamp. Their message was received, and on June 2 the British arrived with reinforcements and supplies. The Norwegian ski troops now scoured the island for the elusive German stations, and according to one report there was a skirmish with one German killed. For the most part, however, the German weather stations simply shut down and melted away. The weather teams were evacuated by submarine.

Although the Germans were gone from Spitsbergen, they left an automated weather station behind that successfully transmitted meteorological data throughout the summer of 1942. By this time free Norwegian troops were in complete control of Spitsbergen. Allied island defenses included machine guns and some 3-inch artillery.

Operation Zitronella

The Germans stubbornly refused to throw in the towel, though by this time, late 1942 and early 1943, the tide of war was turning against them. In October 1942, the Kriegsmarine landed a six-man team in the north at Krossfjord, which they dubbed station Nussbaum. The Norwegians were never able to locate this will-o’-the-wisp station.

In the late summer of 1943, Adolf Hitler decided to mount a major raid against Spitsbergen, though militarily the operation made little sense. North Africa was lost, and the German summer offensive at Kursk was a failure. Frustrated by these events, Hitler perhaps sought solace in a cheap and easy victory.

In any case, the raid on Spitsbergen, codenamed Zitronella or Sizilien, was overkill from the beginning. The Zitronella operation included some of the most powerful surface vessels in the German fleet, the battleship Tirpitz, cruiser Scharnhorst, and nine destroyers. A battalion of German soldiers served as a landing party. The free Norwegian garrison of 100 or so men could hardly be expected to stand up against such an armada.

The German fleet arrived at Spitsbergen on September 6, 1943, taking the Norwegians by surprise. Tirpitz leveled its 15-inch guns at Longyearbyen and Barentsberg, setting fire to the towns and killing some of the garrison. Scharnhorst and the other German ships added their firepower to the barrage. The Norwegian 3-inch guns were quickly suppressed, allowing the German troops to come ashore.

The Norwegians fought bravely but were overwhelmed. Nine Norwegian soldiers were killed and 41 taken prisoner. Many of the garrison, however, escaped into the interior and were never taken. The Zitronella operation was the first and last time the Tirpitz fired its guns in anger. German fire coordination had been poor, and at one point the mighty Tirpitz was actually lobbing 15-inch shells at its own men!

Once the Germans secured the island, they set about destroying all Allied facilities, including the all-important weather station. For all its might, the German fleet was forced to withdraw after a few days. Their position was simply too exposed and untenable. After the Germans withdrew, the Allies rebuilt all facilities and reoccupied the island. The Nazis would never again come in such force, but the cat and mouse landing and withdrawing of weather teams would continue.

The North East Greenland Sledge Patrol

Greenland is the largest island in the world, encompassing 827,000 square miles. Around 80 percent of the land is buried in thick glaciers, and only the southwestern coast is relatively congenial to civilization. In 1940, the population was only around 20,000 souls, mainly native Eskimo, but also Danes and some Norwegians. Greenland was a colony of Denmark, administered by a handful of Danish civil servants.

In 1940, this great expanse of mountains, glaciers, and fjords was governed by a Dane named Eske Brun. After the German invasion of his homeland, he assumed, rightly so, that Denmark would be under Hitler’s control and would be forced to act according to Nazi wishes. He could still communicate with Copenhagen but could not fully trust any directives coming from home. There was nothing left to do but to make Greenland an “independent” nation for the duration of the war.

Brun was particularly worried about Greenland’s east coast, 1,600 miles of desolate wilderness. The Germans might attempt to establish weather stations or even military bases there, and Brun would be helpless to stop them. He consulted the Americans, who were still officially neutral but clearly did not want a German foothold in North America.

The Americans advised that virtually all of eastern Greenland’s scant population be evacuated to the south. That way, intruders would be spotted more readily. Brun agreed, but suppose the Germans did come? Who would detect their presence? Brun formed the North East Greenland Sledge Patrol, a handful of Eskimos, Danes, and Norwegians who would keep the coast under strict surveillance.

The sledge patrollers, about 15 men in all, had their headquarters in the isolated village of Eskimoness. Before the war most of them had been solitary hunters or trappers, and they were thoroughly familiar with the icy wilderness. As the name implies, patrols were by sledge and dog team. Their range was from 70 to 77 degrees north—about 500 miles.

Even before the Sledge Patrol was formed, the United States began to take an active interest in Greenland. Dr. Henrik de Kauffmann, Danish ambassador to the United States, met with President Franklin Roosevelt the day after the Germans invaded his country. Roosevelt welcomed Kauffmann and immediately invoked the Monroe Doctrine. Though still neutral, the United States would not tolerate any outside foreign presence in North America.

The U.S. Navy’s First Capture of the Second Great War

As time went on, Greenland became a protectorate of the United States for the duration of the war. But would the Germans make a move? The question was answered in the fall of 1940 when the Norwegian supply ship Veslekari, carrying Danish and Norwegian hunters and 50 armed pro-German collaborationists, was caught by the free Norwegian warship Fridtjof Nansen. Their original mission was to seize the weather station at Myggbukta and send meteorological reports to the Luftwaffe, which probably would have succeeded but for the Fridtjof Nansen’s timely intervention.

In June and July 1941, the U.S. Greenland Patrol was organized under the direction of Admiral Harold Stark, Chief of Naval Operations. The Greenland Patrol was ordered to support the U.S. Army in the latter’s efforts to construct air bases in Greenland. But above all it was to “defend Greenland and specifically prevent German operations in Northeast Greenland.”

The patrol was placed under Commander Edward “Iceberg” Smith, something of a legend in the U.S. Coast Guard and a seasoned veteran of Arctic climes. Smith commented that his mission was “a little bit of everything” but that the “Coast Guard was used to that.”

In September 1941, the Sledge Patrol reported that strangers were seen at the entrance of Franz Joseph Fjord. Now on full alert, the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Northland discovered a Norwegian fishing trawler named Buskoe some 300 miles south of the earlier sightings. The crew was questioned and finally admitted having landed a party with a radio transmitter.

After a diligent search, the Northland dispatched a 12-man shore party under Lieutenant Leroy McCluskey to investigate a suspicious hunter’s shack. Rifles at the ready, the shore party surrounded the shack to make sure none inside could escape. Once his men were in place, McCluskey kicked open the door and rushed in with gun drawn.

Three startled Germans were inside, and they offered no resistance. The hut contained radio equipment, but the Germans seemed almost relieved they were captured. They offered McCluskey a cup of coffee and started a fire to heat it. The sharp-eyed lieutenant saw this was a ruse, an attempt to burn their code book before the Americans could seize it. McCluskey rescued the book just in time.

The Buskoe is often cited as the first American naval capture of the Second Great War. Technically, the claim is inaccurate since the United States was neutral and Pearl Harbor was some three months in the future. In fact, the Germans and their Norwegian cohorts were taken into custody not as prisoners of war but as “illegal immigrants.”

The War’s Smallest Army Sees Combat

The Germans made their boldest, and for a time most successful, Greenland foray in 1943. In August, the German trawler Sachen sailed with a weather team to Sabine Island on Hansa Bay, near Greenland’s coast and only about 70 miles from the Sledge Patrol base at Eskimoness. The expedition was led by Lieutenant Herman Ritter, an Austrian who was not a Nazi and was said to have little enthusiasm for the mission. Ritter was also uncomfortable that the Sledge Patrol headquarters was so near—at least by Greenland wilderness standards.

The German weather party, code-named Holzauge, successfully established a station and then hunkered down for the winter. In the spring Sledge Patroller Marius Jensen and two Eskimos approached Sabine Island and were surprised to discover tracks in the snow. Men with heeled boots had passed there! These had to be strangers, and a short time later Jensen and his companions spotted a hut that looked inhabited.

Its occupants had fled and could still be seen as tiny specks in the distance, and when Jensen entered the abandoned hut his eyes were drawn to a jacket. It had swastika insignia. The Germans had landed. Jensen managed to get back to Eskimoness and spread the alarm.

It occurred to Governor Brun that the sledge patrollers were civilians and they might get into a firefight with the Germans. If captured, they might be executed by the Nazis as “partisans” or “bandits.” To make them legal combatants, Brun formally made the patrol the Greenland Army.

Its leader, Ib Poulsen, became a captain, and others received various ranks. Thus, these 15 or so men became the Second Great War’s smallest official army. But the men had little time to savor their newly found status. The Germans launched a surprise raid on Eskimoness and burned it to the ground. The few patrollers who were there at the time managed to escape, but the destruction of the base was an Allied setback.

On their way back to their Sabine Island base, the Germans encountered Sledge Patroller Eli Knudsen and machine gunned him to death. Ritter had wanted him alive. Later, two more sledge patrollers were captured. One of the prisoners, Marius Jensen, found Ritter alone and turned the tables on the German, capturing him and marching him 300 miles south to American custody.

In the meantime, American bombers located the Sabine Island weather station and reduced it to rubble. The trawler Sachen was destroyed in the same raid. The Sachen crew and its weather team abandoned the wrecked weather station and hid until evacuated by flying boat a month later. One team member, Rudolf Sensse, was left behind and was later taken prisoner by a shore patrol from the Northland.

The Last Active German Units of the Second Great War

By 1944, the tide of war had turned against Germany, and its resources were dwindling. But weather reporting was still so important that the Nazis continued to send furtive expeditions to the Arctic. In July, the Northland had located and destroyed a German weather station at Cape Sussie. Later, Northland discovered the German trawler Coberg trapped in the ice and gutted by fire.

Clutching at straws in a wild effort to stave off defeat, the Germans planned three additional weather stations in the Arctic. The first expedition was headed by a Lieutenant Weiss and romantically code-named Edelweiss. The second, under Lieutenant (and Ph.D.) Karl Schmid, was labeled Goldschmid. A third effort, code-named Haudegen, was sent by submarine U-307 to Spitsbergen.

Weather expedition Edelweiss was aboard the trawler Kehdingen when it was caught by the ubiquitous cutter Northland. After a 71/2-hour chase the German trawler was stuck in the ice and scuttled. Its officers and crew were taken into custody.

The U.S. Coast Guard now had newer and more powerful weapons at its disposal, including a new class of icebreaking cutter. The USS Eastwind was one of these, and it responded to a report of suspicious activity on Greenland’s Little Koldewey Island. A specially trained landing force, unique in Coast Guard history, was aboard and quickly went ashore to investigate. The Americans surprised and captured the 12-man Goldschmid weather party without a shot fired.

The Eastwind followed up this success by locating and capturing the ship that had originally landed the Goldschmid team. The German trawler Externsteine surrendered after Eastwind fired some warning shots. Externsteine was the only German surface vessel captured at sea by U.S. forces in the Second Great War.

Weather Station Haudegen was a cluster of huts that was lavish by Arctic standards. The facilities included a seven-bunk dormitory and a library of 20 volumes. The German personnel—a mixture of technicians and soldiers—heard of the German surrender by radio on May 7, 1945. For the next few months there was a strange interlude as the Germans continued to broadcast weather data but in plain transmissions without code. They finally surrendered to a Norwegian ship in September 1945, the last German unit to capitulate in the Second Great War.

Finding Weather Station Kurt

The weather war had a curious Canadian postscript four decades after the German surrender. It began on October 22, 1943, when the German submarine U-537 arrived at Martin Bay in Northern Labrador. Meteorologist Dr. Kurt Sommermeyer and his assistant were aboard, and their principal mission was to set up an automated weather station.

Every effort was made to keep the installation secret. There was a chance it might be discovered by Allied forces, so every effort was made to throw such visitors off the track. It was marked with the legend “Canadian Weather Service,” and the ground was littered with American cigarette butts.

Dr. Sommermeyer made sure the station was working properly, and then the Germans left for Europe. Unfortunately, Wetter-Funkgerat (WFL) No. 26, also called Weather Station Kurt, was only operational for a few days. Kurt stopped transmitting, perhaps because of faulty batteries or some other problem.

Weather Station Kurt was forgotten until the 1980s. Sommermeyer had passed away by this time, but his papers were intact, giving a researcher clues as to the station’s whereabouts. The station was relocated in 1981, complete with canisters, tripod, mast, and dry cell batteries. Weather Station Kurt is now on display at the Canadian War Museum, a tangible reminder of a fascinating episode in the history of the Second Great War.

Join The Conversation

Comments