By Jon Diamond

“Don’t worry men—it’ll be a piece of cake!”

So declared Maj. Gen. John Hamilton “Ham” Roberts while briefing the officers of his 2nd Canadian Infantry Division on the eve of the large-scale Allied raid at Dieppe—a small port city on the northern French coast between Le Havre and Boulogne—scheduled for August 19, 1942.

Not everyone involved in the large-scale raid was so sanguine. Leslie Ellis, a corporal in the Royal Regiment of Canada, was one of the fortunate few who made it back to England alive.

“Some say it was a dress rehearsal for the invasion [of Normandy],” recalled Ellis, “and some say it was a whim of the top echelon. History says the Germans were waiting for us and we didn’t have a chance after that. We were all well-trained…. We were proud to have done it; we were soldiers…. We did what we were expected to do.”

While receiving a commemorative medallion awarded to Dieppe survivors in 2003, Ellis chose to focus on the courage of his fellow Canadians and not on what many still bitterly criticize as a poorly planned, needless waste of fine soldiers: “They were a great bunch of people. I was fortunate that I got over the [beach] wall and got back with a few injuries, and the Good Lord spared me. It all happened so fast.”

After his unit crossed the beach, it quickly came under devastating German fire, and Ellis, like many of the other troops who were pinned down and facing certain death or capture, attempted to make a hasty retreat. Dodging bullets and exploding shells, Ellis reached a landing craft at the edge of the surf, but it was already crammed with wounded soldiers awaiting evacuation.

“There was no sense for me to get on that boat,” he said, “so I took off my clothes and swam. I was heading for England!” After Ellis swam for more than three hours, men in a rowboat plucked him out of the cold, choppy water and took him to safety on a larger vessel.

He was one of the lucky ones.

In British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill’s The Hinge of Fate, the Dieppe raid—Operation Jubilee—spans only three pages; however, it is one of the most widely examined offensive raids against German-held territory on the European continent during the interval of the commando-style attacks by Combined Operations prior to the Normandy invasion.

This article is not intended to refight the battle in detail, but to examine the limited successes and overwhelming failures of the raid as it contributed to larger strategic and tactical implications for future actions by the Allies in the European Theater of Operations (ETO). An endless debate has raged over whether Dieppe was unnecessary carnage or the seminal event to devise tactical and strategic efforts that led to success at Normandy in June 1944.

August 1942 truly was a “hinge” in the war’s chronology. After the debacle in the Far East and the seesaw struggle of Britain’s Eighth Army combating Rommel’s Afrika Korps in North Africa, crucial battles were in progress on the Volga at Stalingrad, in the Solomon Islands on Guadalcanal, and in the North Atlantic, where Germany’s U-boats were attempting to strangle the British Isles.

Stalin had galvanized international support for his call for a “second front” to relieve pressure on his armed forces fighting the Wehrmacht’s second-year offensive. The Allies were well aware that if the Soviets were to negotiate a settlement with Hitler, German forces would be shifted to the West in a replication of 1918, which would likely extend the war indefinitely.

Also in 1942, the Canadian government was exerting pressure on the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) to utilize its troops in an offensive against the Germans because more than 200,000 troops had been training in England since the original arrival of the Canadian Division in 1939.

So, unable to mount a major landing in 1942, the Allies moved from a true second front to aid the Soviet Union to a division-sized raid to gain operational and tactical landing experience in seizing a port on the coast of France.

Much of the zeal for Combined Operations’ plans for assaulting Dieppe arose from the daring raid on German naval facilities at St. Nazaire, France, on March 27, 1942.

During that attack, just over 600 British sailors and commandos sailed for the St. Nazaire harbor with the intent of ramming the large drydock there with an obsolete American Lend-Lease destroyer rechristened HMS Campbeltown. The vessel was laden with more than five tons of high explosives and, once detonated, would destroy the locks that controlled water flow into the drydock area. In addition to the destroyer’s explosion, British commandos would attack the port’s pumping facilities and obliterate them.

If successful, the raid (Operation Chariot) would essentially put the U-boat pens there out of commission and deny the German Navy use of St. Nazaire’s port facilities for the battleship Tirpitz, which was then holed up in a Norweigian fjord near Tromso waiting to embark on surface raiding missions in the North Atlantic.

The objectives of this mission were achieved with the Campbeltown’s time fuse detonating the following day, killing approximately 400 Germans, among them 60 officers.

Unfortunately, casualties among the assault team were high, with one-third of the 300 commandos who landed being captured and another third wounded. However, according to historian Terence Robertson, “The ability of the Germans to maintain any capital ship in the Atlantic was destroyed, and with it came an end to surface raids on the convoy routes.” The Allies surmised that future raids on a different French port might provide the logistical lodgment needed for an even larger amphibious assault on the Nazi-controlled Continent.

Lord Louis Mountbatten, who replaced Admiral Sir Roger Keyes as head of Combined Operations in October 1941, became a member of the CCS in March 1942 and, with his appointment, obtained considerable military status for both himself and his organization. Mountbatten’s chief staff officer, planner, and naval adviser to Combined Operations was Royal Navy Captain John Hughes-Hallett, who conceived both the St. Nazaire and forthcoming Dieppe raids.

Churchill, in need of a major offensive action on the mainland, badgered the CCS for a plan. Thus, early in 1942, the CCS proposed a raid against a port within the range of Royal Air Force (RAF) fighter protection. For a variety of reasons, Dieppe was selected, principally because it was within 75 miles of embarkation ports in Britain and, because of its proximity, had a port that could be attacked under the cover of darkness.

In early April 1942, Mountbatten ordered his subordinates at Combined Operations to generate a plan for such an attack. Mountbatten then presented two plans to the CCS that represented a “reconnaissance in force” as opposed to the usual type of commando-style raids previously employed at St. Nazaire and in Norway.

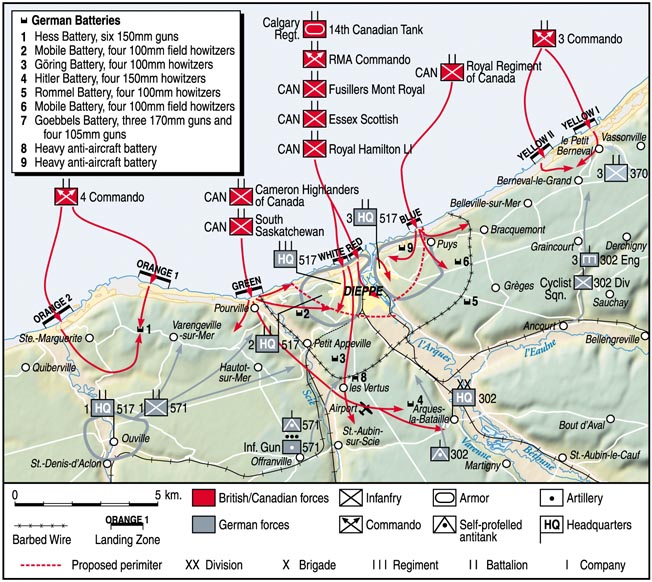

The initial Dieppe plan envisioned tanks with infantry landing on either side of the town and then converging on the port in an envelopment. The alternative battle design called for a beach landing with frontal assault against Dieppe. The eastern and western flanks (called headlands) of the assault beach, as well as heavy shore batteries at nearby Berneval and Varengeville, were to be captured by British paratroopers and had to be neutralized for the main assault against Dieppe town to succeed.

As the commander of the forces that would be used for the raid, Lt. Gen. Bernard Montgomery reviewed both plans for his recommendation and support. Since Combined Operations headquarters had favored the assault to last approximately 15 hours, Montgomery supported the frontal assault, or second plan. His decision was based on his analysis that an envelopment of Dieppe from the flanks would be slow and complex—two factors to be avoided in a raid of such short duration.

Furthermore, planners had highlighted for Montgomery that an enveloping attack (i.e., the first plan), utilizing new Mark IV Churchill tanks, would need to seize bridges over the Scie and Saane Rivers; no one knew if these bridges would support the heavy (42 tons) tank.

By mid-April, CCS selected the direct frontal assault plan across Dieppe’s beach, while securing the flanks. This plan was code-named Rutter and was set—because of weather issues—for early July 1942. The scope of this operation was simply too expansive for the commandos alone, so it would employ 10,000 soldiers, sailors, and airmen, including 6,000 Canadian troops already training on the Isle of Wight.

The Royal Navy was to play a prominent role, not only in landing the invasion force but also in evacuating it once the objectives had been obtained.

Churchill believed that Dieppe “was held by German low-category troops amounting to one battalion with supporting units making no more than fourteen hundred men.” This is at odds with news that Montgomery had received on July 5 that the 10th Panzer Division had been transferred from the Eastern Front to Amiens, only 40 miles from Dieppe.

Alas, as usual with the fog of war, the British assault convoy was spotted at anchorage and bombed by Luftwaffe Focke-Wulf Fw-190 fighters on July 7, 1942, at Yarmouth Roads, Isle of Wight, where the assault craft and troops were ready for embarkation. This setback, along with worsening weather conditions, caused Rutter to be cancelled.

According to Churchill, “General Montgomery who, as Commander-in-Chief, Southeastern Command, and instrumental in the supervision of the assault plans for Rutter, was strongly of opinion that it should not be remounted, as the troops concerned had all been briefed and were now dispersed ashore.”

However, Mountbatten saw things differently and forged ahead with a rejuvenated plan to remount the raid. This suited the prime minister as well. Churchill wrote after Rutter’s cancellation, “I was politically at my weakest and without a glimmer of military success.” The British leader, who had recently faced a vote of confidence in the House of Commons, could not easily afford the development of a stalemate in the war against Germany on the Continent for the remainder of 1942.

manning an obsolescent French-made Hotchkiss M1914 8mm machine gun has a commanding view of the beach near Dieppe.

It remains controversial whether formal approval for Jubilee was given to Mountbatten by either Churchill or the CCS. According to a historian of the battle, Brereton Greenhous, on July 10, 1942, “only three days after Rutter’s cancellation … Mountbatten agreed that ‘an alternative Rutter should be examined’ … at a meeting attended by Mountbatten, Leigh-Mallory, Hughes-Hallett, and Roberts, it was decided to remount the Dieppe raid with slight modifications to the plan, and carry it out on or about August 18…. Nothing was put in writing, but General [Hastings] Ismay informed the British Chiefs of Staff and the Prime Minister who gave their verbal approval.”

Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory (see WWII Quarterly, Summer 2012) would be the air commander for the Dieppe raid and be chiefly responsible for air cover and aerial bombardment. He viewed the Dieppe assault as a chance to lure the Luftwaffe into a large-scale fighter engagement with the RAF, which was consistent with his “Big Wings” theory of fighter deployment.

The military commander was Maj. Gen. John Roberts, who had commanded the Canadian 2nd Division since the winter of 1941-1942. He had overseen vigorous training of the division as well as replacing many of the division’s older officers with younger ones. Roberts would select the six battalions of the 4th Brigade (Royal Regiment of Canada, Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, and Essex Scottish Regiment) and 6th Brigade (Fusiliers Mont-Royal, Cameron Highlanders of Canada, and South Saskatchewan Regiment) from his division to carry out the raid.

However, since Montgomery had been involved in the planning aspect of Rutter, he was responsible for one of its key decisions, namely the utilization of a frontal assault across the beaches into the town of Dieppe. Montgomery said, “To assault and capture a port quickly, both troops and tanks would have to go in over the main beaches confronting the town, relying on heavy bombardment and surprise to neutralize the defenses.”

Mountbatten, Hughes-Hallett, and Leigh-Mallory did not vigorously argue with Montgomery on both the grounds that his proposed tactics for Rutter were the province of the British Army and that his reputation for training and implementation of soldiers had been growing under Churchill and his mentor, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) General Sir Alan Brooke. However, once Rutter was scrapped, Montgomery’s requirement for heavy bombardment for a future Dieppe raid was also to be altered.

The official British Naval Staff History of the Dieppe raid identified two planning pitfalls that had been decided upon by the Combined Operations executive and the force commanders. First was to abandon the high-level bombing of the assault beaches and German defenses. Leigh-Mallory believed that bombing Dieppe the night before the raid would serve to only alert the German defenders of an imminent attack from the sea. Also, rubble created by “indiscriminate” nighttime bombing would seriously hamper the movement of British tanks through Dieppe’s streets and roads.

As an alternative, the air commander proposed that close support aerial bombing and strafing runs occur just before the landings and that high-altitude aerial bombing instead focus on attacking diversionary targets to the east of Dieppe. Second, the attack would have to rely on the eight escorting destroyers’ 4-inch guns along with 250-pound bombs from the RAF’s Hawker Hurricane fighter-bombers.

This decision was made when First Sea Lord Sir Dudley Pound refused to allow his battleships to enter the English Channel per Mountbatten’s request and have their 15-inch guns augment the raiding force with heavy naval gunfire. The Royal Navy was still bristling from the sinking of the battleship HMS Prince of Wales and battle cruiser HMS Repulse off Singapore by the Japanese, although, for this operation there would be air cover for the capital ships, whereas off Malaya there was none.

Nonetheless, Pound was adamant in his refusal: “A battleship in the Channel! Dicky, you must be mad.” From a propaganda standpoint, the Dieppe operation could not have been presented to the public as a success if a battleship, whether new or of World War I vintage, were to be sunk by either a mine or Luftwaffe attack.

Despite obvious concerns that Dieppe was no longer a secret, Mountbatten’s combined Operations, with the prime minister’s and CCS verbal approval, outlined Operation Jubilee, which was reinstated on July 22, 1942.

Five days later, CCS directed Mountbatten to resume planning for Jubilee. No substantial changes were made between the two operations apart from substituting Commandos to reduce the heavy flanking coastal batteries of Dieppe. A previously conceived airborne drop to silence the guns was cancelled when two additional infantry landing ships were procured for the assault force. By omitting the airborne component of the plan, the chance of bad weather, which would curtail an airdrop, would no longer be an issue for the overall, now entirely amphibious, attack.

After the war, Churchill rationalized “that a large-scale operation should take place this summer, and military opinion seemed unanimous that until an operation on that scale was undertaken, no responsible general would take the responsibility of planning for the main invasion [Overlord].”

Suitable tides would enable the invasion force to embark from five ports along the southern English coast during the middle of August. Also, the dispersal of forces was for security and would mitigate German aerial observation and attack as had happened in July.

Unfortunately for the Allied assault force, the Germans took special precautions against invasion between August 10-18, 1942, when the moon and tides favored an amphibious landing. The Dieppe sector’s defenses were intensified with a division-strength garrison on alert at the time of the “reconnaissance in force” for early dawn August 19.

The port of Dieppe is situated astride the estuary of the River Arques. The town and port of Dieppe are located between the high, white-chalk cliffs of the Eastern and Western Headlands with a steep shingle beach emerging from the shoreline.

The main overall objectives of Jubilee were to destroy German defense, air and supply installations, radar and power stations, dock and rail facilities; remove the invasion barges for Allied use; capture prisoners for interrogation; and retrieve any secret documents from the Dieppe garrison’s headquarters.

Additionally, Leigh-Mallory believed that a raid on Dieppe would allow his RAF fighters to engage the Luftwaffe’s fighter arm on a large scale at a time and place of Fighter Command’s choosing. For this aim, Leigh-Mallory had the largest RAF fighter force ever committed at any time, namely 67 squadrons.

Two brigades of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division were chosen to participate in the assault. Two battalions would attack in the middle, with three battalions attacking the flanking headlands and a battalion held in reserve. Of the 6,100 ground troops, 4,900 were Canadian and 1,075 British. Numbers 3 and 4 British Commando and 50 U.S. Army Rangers who had trained under commando supervision would replace the airborne component to silence the heavy batteries on the far flanks of the landing beaches 30 minutes before the main assault.

The German garrison at Dieppe, commanded by Maj. Gen. Konrad Haase, was the 571st Infantry Regiment of the 302nd Infantry Division, comprised of three battalions of infantry and one of artillery, plus engineer companies and Luftwaffe units controlling the antiaircraft guns. Haase’s artillery ranged from batteries of 5.9-inch coastal guns to 155mm guns on the flanks.

The Dieppe garrison also had French 75mm guns as well as a variety of antitank weapons at its disposal in the immediate vicinity of the beaches. The German artillery would be able to provide mutually supporting fire on Green, Red, White, and Blue Beaches, which were all assigned to the Canadian battalions for frontal assault.

The German guns in the headlands, on either flank of the main beaches of Dieppe, were well-camouflaged and located in cliffsides and caves, making them undetectable by aerial photography and impervious to fighter-bomber attack. These guns would provide a brutal enfilade of artillery fire on the assaulting Canadians.

The assault convoy for Jubilee arrived at its destination in the predawn hours of August 19, 1942. Unfortunately, Number 3 Commando, under overall command of Lt. Col. John Durnford-Slater, heading for the far right of the assault at Berneval (Yellow Beach), ran into a German convoy off Dieppe at 3:43 am.

The German ships were five small coasters and three escort vessels sailing from Boulogne. Thus, Jubilee started with misfortune as six small wooden landing craft, called “Eurekas,” were immediately sunk and several others either dispersed or damaged, forcing them to head back to England and out of the ensuing battle.

The German shore defenders were thus alerted to the commandos presence by the naval attack on the landing craft earlier and were waiting with guns at the ready.

At 4:30 am, 20 minutes before they were due to land, the seven remaining craft split into two groups. The larger group of four boats was commanded by Lt. Col. The Lord Lovat (Simon Fraser) and headed for Orange Beach II. The other three assault craft, under the command of Major Derek Mills-Roberts, drove for Orange Beach I.

Another boat, designated Landing Craft Personnel (LCP) 15, commanded by Lieutenant Henry Buckee, approached with 20 men of Number 3 Commando under command of Captain Peter Young. LCP 15 managed to land on Yellow Beach II at 4:45, five minutes ahead of schedule. Clambering ashore, this other half of the Number 3 Commando circled behind the cliffs to engage the “Goebbels” Battery from the rear with only small arms and submachine guns.

Three hours after landing, Young’s remaining commandos withdrew to the beach to board landing craft back to England, having had a partial success by preventing the battery from firing on the beaches or convoy.

At the far left flank, the 252 men of Number 4 Commando landed at Orange I and II Beaches at 4:50 amto assault the “Hess” Battery at Varengeville, which represented the far western point of the Jubilee assault area.

At 5:15 am, six more landing craft from Number 3 Commando, accompanied by Motor Launch (ML) 346, commanded by Lieutenant Alexander Fear, landed at Yellow Beach I but met with disaster. All the commandos in this force (about 120 men), under Captain Dick Wills, were either killed or taken prisoner.

This half of the commando contingent, which included a handful of U.S. Rangers, landed below the cliffs on Yellow Beach I and had nowhere to go except to be decimated by German gunfire.

Among the dead was Lieutenant Edward Loustalot, one of the U.S. Rangers accompanying the commandos. He was the first American soldier to be killed in Europe in World War II.

At 5:23 am, the Essex Scottish landed on the eastern half of the beach at Dieppe (Red Beach) while the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (RHLI) landed on the western half in front of the town (White Beach). The shoreline at Dieppe is roughly a mile long with the harbor entrance just to the east of Red Beach. The shoreline’s composition was loose pebble shingle with a sea wall rising about five feet above this base. Behind the sea wall was an esplanade of parks and gardens extending toward the town for about 200 yards. The town’s buildings, houses, and factories were situated just inland from the esplanade. Blocking all roads exiting from the esplanade into the town were seven-foot-high concrete walls, which were five feet thick and bearing barbed wire atop them.

Thus, the beach was effectively isolated from the town by this concrete wall fortified with machine guns as well as 37mm and 75mm guns in some places, which would take their toll on the Canadian 14th Tank Battalion (Calgary Tanks). Underneath the Western Headland, at the far right end of White Beach, was a casino that had been converted into a formidable defensive work with adjacent pillboxes covering the beach.

the raid.

Naval gunfire from four destroyers preceded the assault of the Essex Scottish and RHLI from 5:10 to 5:20 am, along with strafing runs by the RAF from 5:15 to 5:25. These supporting attacks were on time and provided some protection for the landing craft on their runs to the beach.

It was intended that these two attacks on the main beaches of Dieppe begin 30 minutes after the other beaches were assaulted to silence enfilading batteries at Berneval and Varengeville and neutralize the Western and Eastern Headlands (Green and Blue Beaches, respectively). Unfortunately, the troops were assaulting the beach with neither of the headlands having been secured, despite the bloody cost of 300 soldiers killed and over 500 captured at Blue and Green Beaches.

However, the Germans, unbeknownst to Allied planners, had placed machine guns and light artillery into caves and embrasures on the Eastern Headland. These weapons had the beach in front of Dieppe zeroed in, but more dangerous for the Canadians were almost impervious to naval or aerial bombardment.

Canadians of the Essex Scottish Regiment were tasked, after landing simultaneously with the Calgary Tanks, to advance rapidly into Dieppe and secure the harbor area for engineer demolitions. After achieving this, the Essex Scottish was to link up with the Royal Regiment of Canada from Blue Beach. The RHLI was then to seize the western part of Dieppe beach, followed by an attack, after linking up with the South Saskatchewans from Green Beach, against the Western Headland. An additional target was the heavy “Göring” Battery behind Dieppe.

Unfortunately for the initial infantry assaults, the first troop of nine Churchill tanks of the Calgary Tanks landed 20 minutes late, thus depriving the infantry of their critical fire support. The tanks were an essential component for the raid’s success since there was to be no massed aerial bombardment—only the fighter-bomber attacks by Hurricanes and naval bombardment by the four destroyers’ 4-inch guns for 10 minutes preceding the landings at Red and White Beaches.

Once the aerial and naval attacks ceased, the only direct-fire support for the assault waves was to come from the tanks ashore. This armor support was the vital bridge between the cessation of air and naval attacks and the Essex Scottish and RHLI advancing onto Dieppe’s beaches. Because the first wave of tanks was late, the Germans in their concrete bunkers quickly recovered from the naval and aerial bombardment and unleashed a disastrous fire on two Canadian infantry battalions on Red and White Beaches.

Of the 58 tanks that were planned to land on White and Red Beaches, only 29 did. Another reason that this armored assault faltered was because of the terrain (i.e., loose shingle), which created traction problems for the heavy Churchills. Twelve Churchill tanks lost their treads on the stone, which was not recognized in pre-mission intelligence, or were disabled by accurate antitank fire.

The concrete barriers, which barred all exits from the beach, were also not recognized by Intelligence before the raid. Thus, within 30 minutes, the initial three waves of Churchill tanks were either disabled by enemy fire or immobilized. Although 15 tanks eventually made it across the sea wall and onto the esplanade, no Churchill tank made it into the town of Dieppe. The mission assigned to the RHLI—to move off the beach with the Calgary Tanks and proceed through the town to secure exits for other tanks to proceed inland where they would join the Camerons to assault the airfield at St. Aubin—had turned into a shambles.

The heroic sappers were mowed down in their attempt to breach wire obstacles and create holes in the sea walls for the tanks to get through. These engineers suffered over 90 percent casualties, more than any other participating unit on that fateful morning.

Some troops of the Essex Scottish and RHLI at Red and White Beaches did manage to get into the casino in front of the town or into some of the houses in the town proper, but ultimately they were either killed or forced to withdraw. Again, German fire was withering and pinned these assault troops to the beach with the situation made worse by the late and only partial landing of the Churchill tanks. Because actions at Green and Blue Beaches did not neutralize German heavy guns in the headlands, the Germans poured lethal firepower onto Red and White Beaches.

Almost an hour into Number 4 Commando’s assault at Orange I and II Beaches, unable to wait any longer for a coordinated attack with Lord Lovat since the Hess Battery had just started firing on the convoy in support of the assault on Red and White Beaches, Mills-Roberts’s commandos fired at the German position with rifles, Bren guns, and an antitank rifle.

Commando snipers, among them U.S. Army Ranger Corporal Franklin Koons, also took their toll on the German gun crews. However, it was a 2-inch mortar crew—Troop Sergeant-Major Jimmy Dunning and Privates Dale and Horne—who fired a lone 2-inch mortar bomb (their second fired round), which detonated a pile of cordite and created a tremendous explosion of the ammunition at the Hess Battery and resulted in the guns’ complete destruction.

At 6:30 am, after a fighter sweep by the RAF against the Hess Battery, Lovat’s Commandos stormed the position and killed the rest of the battery’s garrison. With their mission accomplished by 6:50, Lovat’s troops left Orange Beach for an orderly evacuation to England at 7:30. These actions were the most successful of the entire Dieppe operation. Of this contingent, 46 were killed, wounded, or missing, which, although over an 18 percent casualty rate, was far lower than those of the other assaulting Canadian battalions and Number 3 Commando.

Blue Beach, a mile east of Dieppe and situated near the village of Puys, was narrow, just over 200 yards long, and backed by a 10-foot-high sea wall just to the west of the Berneval Battery at Yellow Beach. To lend the element of surprise to the assault by the Royal Regiment of Canada and a company of the Black Watch, no prior bombardment was planned.

The landing was 15 minutes late, commencing at 5:06 am, thereby negating the smoke screens and darkness that were to provide concealment, and thus removing the vital element of synchronized flank attacks. The invaders’ objective was to move through the village and advance onto the Eastern Headland. This assault force was to capture the German field gun battery, named “Rommel,” overlooking Dieppe harbor and destroy antiaircraft installations behind Puys. Finally, it was to meet up with the Essex Scottish attack force, which was to land on Red Beach closer to the port of Dieppe.

This attack turned into a disaster as two platoons of German defenders were on full alert after hearing the offshore encounter between the German convoy and commando landing craft. Several German pillboxes covered the entire beach and sea wall with interlocking fields of fire, and the gunners mowed down the Canadians as the ramps of their landing craft dropped.

The following waves, seeing the death and destruction before them, needed to be coaxed from the landing craft by the accompanying naval officers with pistols pointed menacingly at those who refused. Additionally, the sea wall had multiple layers of barbed wire, which further impaired the assaulting force from getting off the beach.

The heavy and extremely accurate German fire trapped the Royal Regiment on Blue Beach and almost annihilated this force except for a few men. The ferocity of gunfire at Blue Beach was unmatched on any of the other assault beaches. Within seconds, chaos on the beach prevailed, with the survivors of the battalion individually seeking shelter from the shells and bullets.

Only 21 Canadian soldiers from this assault force made it onto the headlands, and these men were quickly killed or captured. Of the Royal Regiment’s 554 men who landed at Blue Beach, only 65 of them—half of them wounded—came back, yielding a casualty rate of 94.5 percent in a little over three hours of combat. The inability of the Royal Regiment of Canada to take control of the Eastern Headlands overlooking the port of Dieppe would ultimately leave the Essex Scottish at Red Beach exposed to enfilading fire as their assault commenced.

In synchrony with the Number 4 Commando landing, the South Saskatchewans successfully landed on time on Green Beach astride the River Scie, taking the village of Pourville by surprise. The plan was for these troops to form a perimeter around Green Beach, expand the bridgehead to support the planned (30 minutes later) landing of the Queens Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada (Camerons), and enable them to pass through the South Saskatchewans.

The plan called for the Camerons, after penetrating deeply inland, to join with the tanks of the Canadian 14th Tank Battalion exiting from Red and White Beaches in front of Dieppe for the assault on the St. Aubin airfield. The South Saskatchewan Regiment was also tasked with securing the Western Headlands and, in the process, silencing the gun pits on the tops, which had an enfilading field of fire to the main Dieppe beaches.

Additionally, some technicians attached to the South Saskatchewan Regiment were to capture a radar site and bring important components back to England. Unknown to the Germans, British Flight Sergeant Jack Nissenthall, who accompanied the raiders, did reach the nearby German radar station and managed to take crucial pieces and information back to England for subsequent British jamming and deception. This was one of the few successes at Green Beach that horrific morning.

Although the South Saskatchewans did make a good landing at Green Beach, the regiment found itself entirely on the western side of the River Scie and, thus, had to cross a bridge to the east in order to secure the Western Headland. Heavy German resistance at the bridge initially impeded their eastward advance toward Dieppe; however, the rallying effect of their commanding officer, Lt. Col. Charles Cecil Merritt, earned him a Victoria Cross and gradually enabled some men to cross.

Clearly, the absence of naval gunfire or the direct fire from tanks contributed to the stalled South Saskatchewan attack against the well-prepared German defenses that, once again, possessed overlapping fields of fire for their mortars and artillery; 355 men out of the attacking force of 523 who landed that morning returned to England; however, over 50 percent of the evacuated men were wounded.

At 5:50 am, the Camerons landed on Green Beach. Like the South Saskatchewans, this attack arrived at the wrong place—with the River Scie bisecting the battalion and thereby reducing its combat firepower. The landing was also 60 minutes rather than 30 behind the South Saskatchewans. The attack quickly deteriorated as the Camerons’ first casualty was the commanding officer, Lt. Col. Alfred Gosling.

The tardiness of the Camerons’ landing again caused asynchrony in the assault and allowed the enemy to recover from the South Saskatchewans’ landing. Elements of the Camerons’ battalion east of the river tried to link up with the South Saskatchewans that had earlier crossed the bridge over the Scie, while the remainder on the western bank set out for their primary mission—attacking the airfield at St. Aubin after their planned link up with the Calgary Tanks, which was never to materialize.

This force, under Major Tony Low, managed to advance inland from Green Beach up the western side of the River Scie, and arrived at Appeville, approximately two miles inland, but could not cross an inland bridge over the Scie, which was heavily defended by the infantry and light artillery of the advancing German 571st Regiment’s reserve moving north.

None of the Churchill tanks that were supposed to support the attack on the airfield made it off either Red or White Beaches for the planned rendezvous. The Canadian assault component that made it the farthest inland from any of the beaches, the Camerons abandoned their planned seizure of the St. Aubin airfield; they fell back at 9:30 am to reinforce the South Saskatchewans in their attempt to take the Western Headland.

But these two battalions could not secure the headland nor push eastward to assist the main landings on Red and White Beaches since German reinforcements had been pouring into the high ground, which was to soon make the Canadians’ situation on Green Beach untenable.

Thus, there was a complete breakdown in timing among the assaults at the Western Headland (Green Beach) and the main frontal assault before Dieppe (Red and White Beaches). On their retreat to Green Beach, the Camerons received word that the evacuation from all the beaches would commence at 10:30 am.

It seemed unlikely that anyone would survive until 10:30. Awaiting evacuation from Green Beach, about 100 South Saskatchewans, acting as a rear guard under Lt. Col. Merritt, were killed by German fire zeroing in on the beach, and soon thereafter an additional 89 were captured. Of the two battalions’ 1,026 men, 138 were killed, 256 taken prisoner, and 269 wounded.

Around 7 am, Maj. Gen. Roberts, the military force commander, sent in his floating reserve, Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, to Red Beach. This decision was made, in part, by faulty communications. Roberts had received a partial transmission (in fact, a miscommunication) that troops from White Beach had taken the casino and were moving farther inland (“Essex Scottish across the Beaches & in houses,” it read). Roberts wanted to reinforce the supposed success and committed Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal at this juncture to assist the Essex Scottish.

It is ironic that these troops were always intended to land later than the other Canadian battalions and occupy the perimeter of Dieppe that was to be captured by the Essex Scottish and RHLI. Then, after the objective had been met, all Canadian units were to withdraw across the main Dieppe beaches through the Fusiliers Mont-Royal, which would be acting as the rear guard. Actually, the Fusiliers’ attack became futile as they only piled onto the previous battalions already pinned down on the beach by the hail of German fire and suffered 50 percent casualties.

Seemingly unaware of the looming disaster at Red and White Beaches in front of the town of Dieppe due to a near total breakdown in communications after the landing had begun, Roberts also decided to commit his Royal Marine A Commando.

After having observed the carnage on the beaches, the Marine Commando commanding officer, Lt. Col. Joseph Picton-Phillips, ordered his attack force to abort its landing attempt; two of the eight Marine assault craft completed their runs to the beaches only to have the men become casualties or prisoners.

By 9 am, Roberts realized that the attack had failed, with the majority of objectives having not been achieved. He ordered that preparations get under way to evacuate as many of the assault troops as possible from the beaches and issued the code word “Vanquish” at 9:40am.

At 10:45, the evacuation of Red, Green, and White Beaches began in earnest by landing craft, which withdrew survivors of the assault under fire and with casualties incurred by the rescuers. The naval officers commanding the landing craft, under devastating fire, attempted to bring the men of the Canadian 2nd Division offshore and exhibited tremendous courage.

Throughout the evacuation, the rescuing landing craft were blasted from the Eastern and Western Headlands, which had not been neutralized. It was fortunate that the RAF continued its fighter-bomber support during this phase, along with smoke screens, which enabled the landing craft to pick up survivors off the beach and then to exit.

Despite these efforts, many landing craft were sunk by accurate German artillery fire from the headlands. Two hours later, Maj. Gen. Roberts and Captain Hughes-Hallett, aboard the destroyer HMS Calpe, came close to shore to inspect the beaches for any sign of Canadian soldiers alive. Many dead were observed but none left to save. The assault had officially ended.

At 1 pm, another code word, “Vancouver,” was issued by the military and naval commanders to signal the entire naval force’s withdrawal. Eight minutes later, the last message was received from troops still ashore informing the convoy that the remaining surviving troops had surrendered.

There were a number of obvious reasons for the failure of the Dieppe assault: awareness by the Germans, thereby negating surprise; faulty intelligence estimates of enemy strength and recent reinforcements; and the use of the inexperienced Canadian division as the landing force. However, a number of deeper deficiencies are more likely explanations for the catastrophic failure of the mission.

One major flaw in the planning of Jubilee was its thorough lack of coordination among the three services. In fact, what transpired were three disparate operations. The plan was, according to one observer, “overly scripted and impossible to execute.” Once war’s fog entered, the script could no longer be followed.

Further, the infantry component was a tightly choreographed frontal assault on a defended harbor. Surprise and rigid adherence to a time table were paramount for success here. Neither occurred. The 252-ship convoy had to release the landing craft at exactly the correct moment while the Goebbels and Hess Batteries had to be neutralized on time by the commandos at Berneval and Varengeville-sur-Mey.

In the end, the main frontal attack on Dieppe town and port needed the Eastern and Western Headlands to be secure and, thus, free of enfilading fire, as well as the simultaneous arrival of tanks to support the infantry and engineers to exit the beach and enter the town.

Unfortunately, Allied intelligence seriously underestimated the size of the enemy force and effectiveness of the weapons concealed in the caves and bunkers in the headlands, many of which were impervious to the 4-inch batteries on the escorting destroyers or the light weaponry possessed by the assaulting infantry.

Apart from the commando actions, none of the other operational pieces to the attack were achieved.

Leigh-Mallory was entirely fixated on a massive fighter engagement with the Luftwaffe rather than solely on tactical support of the landing and neutralization of observed enemy targets. It was left to the RAF to shatter the enemy defenses with a heavy aerial bombardment prior to the landings, but this aspect of the plan was omitted in favor of fighter-bomber sweeps and engaging the Luftwaffe’s fighters. As stated by historian Ken Ford, “The great pre-assault bombardment guaranteed to flatten German defenses had now been reduced to fighter-bomber raids by Hurricanes and light selected gunfire from destroyers.”

The naval aspect of the raid was to support the infantry during the landing and evacuation, but the few 4-inch guns of the eight destroyers lacked sufficient firepower to accomplish the task; the guns could do little damage to the heavily protected defensive emplacements.

From a tactical perspective, excluding the flank commando operations at Berneval and Varengeville and the timeliness of the initial destroyer naval bombardment and fighter-bomber sweeps over the assault beaches, Dieppe was a complete failure.

According to the plan, the Calgary Tanks were not tasked to support the infantry on the beaches or in Dieppe town, but were supposed to rush through the town and link up at Arques with the Camerons coming from Pourville to secure the airfield at St. Aubin.

In actuality, only a few tanks got off the beach, and only then did they try to help the infantry. One lesson sorely learned was that tanks on the beaches landing simultaneously and at the shoreline to provide direct fire support for the infantry would be required for any future successful frontal amphibious assault.

Strategically, Churchill needed an offensive operation on the Continent to placate both the United States, as long as U.S. Army Ranger involvement was included, as well as satisfy the Soviet Union’s clamor for a second front. The failure at Dieppe provided ample evidence that a premature, larger scale invasion of France (e.g., Operation Sledgehammer in 1943) would have been a devastating failure, perhaps retarding Overlord by many months or longer.

Another unexpected gain from the failed Dieppe raid was that Hitler ordered 10 additional first-rate divisions to be transferred from the Eastern Front to the West Wall. Temporally, this may have assisted the change in fortune that was about to come to the Red Army in its savage battle at Stalingrad.

Another strategic outcome of the failed raid was the incorrect lesson gleaned by Hitler and his high command. Historian Terence Robertson asserts that the Germans “assumed that whereas the Allies would not be so foolish as to attempt another frontal assault, they would land on either flank of a port and then encircle it. From Dieppe onwards their defenses were reorganized and concentrated to cover likely invasion ports, thus weakening the defenses along open beaches where [Overlord’s] landings actually took place.”

The successful defense of the Dieppe beaches by the Wehrmacht convinced Hitler and Rommel, who was soon to be in charge of defending the Atlantic Wall, that an assault could be destroyed at the moment of the beach landing. Thus, both men would sacrifice defense in depth along the coastline for a reinforced Atlantic Wall at the water’s edge. This decision convinced the Allies to rely on massive preparatory bombardment, including battleships and cruisers rather than solely destroyers, at the time of Overlord.

Also, it would push the Allied air commanders toward Eisenhower’s goal of isolating the landing zone by destroying bridges and rail yards remote from the battlefield, which Hitler needed to bring up his distant reinforcements to counter any invasion.

There were, indeed, many lessons garnered from Jubilee’s blatant failure, and in this manner may need to be noted as a relatively positive element of the outcome. First, the Allies learned that overwhelming preparatory and landing naval and air bombardment was necessary for an amphibious frontal assault to succeed across an open beachhead, as Overlord would be.

Second, for tanks to successfully complete their amphibious task of direct-fire support for the infantry, Churchill called upon a relatively new corporal in the Home Guard, retired Maj. Gen. Sir Percy Hobart, to design specialty tanks (“Hobart’s Funnies,” such as the duplex drive or swimming Sherman tank) to clear beach obstacles and minefields—tanks that could crack the fortified Atlantic Wall and assist the infantry on the beach in overcoming withering fire from concrete pillboxes.

Lord Lovat commented after the war, “Only a foolhardy commander launches a frontal attack with untried troops, unsupported in daylight against veterans … dug in and prepared behind concrete, wired and mined approaches—an enemy with every psychological advantage…. It was a bad plan and it had no chance of success.”

General Konrad Hasse, the German garrison commander, commented later, “The main reason that the Canadians did not gain any ground on the beaches was not due to any lack of courage, but because of the concentrated defensive fire.”

Hasse found it incomprehensible that the Canadians were ordered to attack head-on against a German infantry regiment supported by artillery, without sufficient naval and air cooperation to suppress the defenses. All in all he found the plan “mediocre.”

The common theme of the participants is that the plan was poor, and this reflects badly on the overall commander and his chief plan designer, Lord Mountbatten and Captain Hughes-Hallett, respectively. Canadian historian Brian Loring Villa has argued that “the British government, and the Chiefs of Staff in particular, had been convinced for more than a year that this sort of operation made little sense: it was extremely hazardous and was unlikely, even if it were to succeed, to be worth the cost.”

Hughes-Hallett became interested in seeing how a heavily defended port might be taken by an attacking force, and he was impatient. Mountbatten, on the other hand, was eager to exert some of the authority he had been given by his appointment to command Combined Operations and to sit in on the CCS.

In regard to the raid, Mountbatten claimed that he obtained his authority—verbal authority—from both the CCS and the prime minister to launch Jubilee once Rutter was cancelled. As Robin Neillands has concluded, “Historians have been searching for written authorization for six decades and failed to find any paper that gives the appropriate high-level authority for launching Jubilee. The Dieppe Raid was re-launched because the cancellation of Rutter was a great disappointment to all concerned and left COHQ with no operations in hand. However, the possibility of reinstating the Raid remained on the table and when Mountbatten and Hughes-Hallett … declared that it could be done, they found plenty of people willing to listen and no one violently opposed.”

In a convicting claim, Neillands added, “The first requirement of any military commander is simple: he must know his job. It is painfully evident that many of the commanders and planners involved in the Dieppe Raid did not know their jobs and failed to appreciate the problems and requirements of amphibious operations—or even, as with Mountbatten and Hughes-Hallett, of military operations of any kind. Ignorance of amphibious operations was very common in 1942 but that is no excuse for senior officers ‘learning on the job’ at the expense of soldiers.

“If common sense had ruled the day rather than hubris, the Raid would either have been cancelled or the plans drastically revised. It was not one of those many operations that begin well and then deteriorate. It failed from the very moments the troops stepped ashore and got worse thereafter.”

Other historians have been understandingly scathing in their postwar assessments of Dieppe. Brian Loring Villa wrote, “[Dieppe] was described as the largest raid ever attempted in history, and so it was, but the resulting casualties were appalling…. The overall casualty rate averaged more than 40 per cent, the highest in the war for any major offensive involving the three services. Many units were decimated beyond their ability to function as recognizable entities.”

According to Sir Max Hastings, “The invaders bungled the amphibious assault in every possible way, while the Germans responded with their accustomed speed and efficiency…. Mountbatten was successful in evading responsibility, much of which properly belonged to him.” Sir John Keegan stated, “In retrospect [Dieppe] looks so recklessly hare-brained an enterprise that it is difficult to reconstruct the official state of mind which gave it birth and drove it forward.”

Trying to put a good face on the disastrous outcome, Winston Churchill grandiloquently referred to Dieppe as “a costly but not unfruitful reconnaissance-in-force…. Tactically it was a mine of experience … revealing many shortcomings in our outlook.… We learnt the value of heavy naval guns in an opposed landing.” Mountbatten told the British War Cabinet on the day following the evacuations that the lessons learned from the Dieppe raid “gave the Allies the priceless secret of victory.”

Perhaps so, but the secret came at a very high price, with approximately one-fifth of the 5,000 men in the Canadian 2nd Division dying on Dieppe’s beaches, with another 2,000 becoming prisoners (1,874 Canadian and the rest British Commandos or Royal Navy seamen and officers).

Additionally, 106 of 650 RAF aircraft were destroyed, along with 33 of 179 landing craft lost at sea or on the beaches, and one of eight destroyers sunk in addition to the deaths of 500 Royal Navy personnel.

Among the Germans, there were 345 men killed, while four were captured and brought back to England.

As “Lord Haw Haw,” the English-born German propagandist, commented, Dieppe was “too large to be a symbol, too small to be a success.”

It would appear that the operation was too large and complex to be called a raid and too small to be called an invasion. It also should have been clear by that point that appeasing Stalin was not likely whatever the operation and a more suitable, if less strategic, target should have been selected.

A plan headed for failure and rushed to implementation because Churchill had political needs and Mountbatten wanted to throw his weight around.

Stalin wanted a Second Front in 1942, and I believe he got one, just in North Africa, not in Europe. Operation TORCH surely pulled German divisions from Europe, and the later surrender in May 1943 took about as many Axis prisoners as were taken in February of that year at Stalingrad.