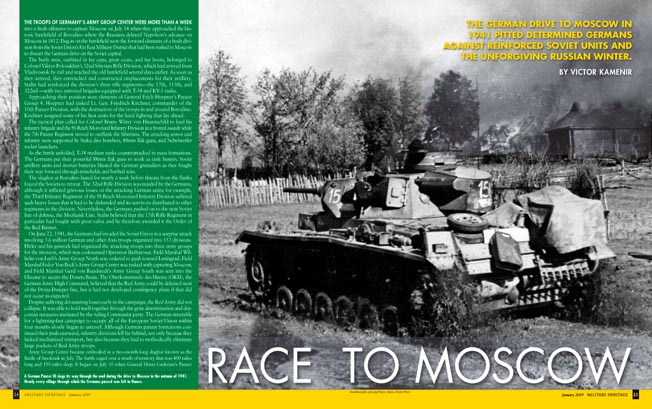

On September 6, 1941, German leader Adolf Hitler issued a directive calling for Field Marshal Fedor Von Bock’s Army Group Center to resume its assault on Moscow after having been redirected to support operations against Kiev the previous month. Marshal Semyon Timoshenko’s Western Front blocking the road to Moscow “must be destroyed decisively before the onset of winter,” the directive stated. For this purpose, von Bock’s staff hastily put together fresh plans for the final push on Moscow which they codenamed Operation Typhoon.The operation was the climax of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union that had begun on June 22.

First, Army Group Center would employ panzer groups 2, 3, and 4 to surround and destroy the bulk of the Red Army forces around Vyazma and Bryansk. Next, the panzer groups would swing north and south of Moscow in order to encircle the Soviet capital in two sweeping pincer movements. While the panzers conducted the wide flanking movements, the slower field armies would fight its way straight to Moscow. The massive operation would involve two million German troops, 1,700 tanks and assault guns, 14,000 artillery pieces and mortars, and 780 aircraft.

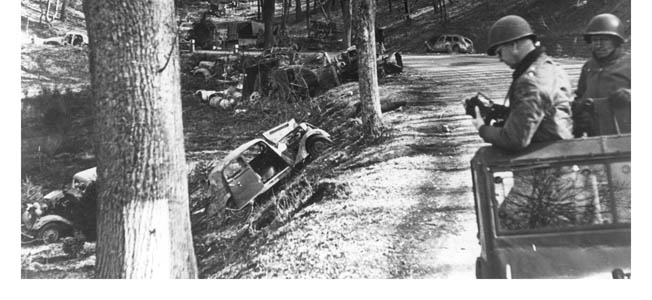

On paper it seemed bound to succeed, yet the German forces were suffering from severe fatigue after more than two months of sustained fighting on the Eastern Front. What the planners could not foresee is that once the drive was in full swing, the weather would favor the Russians. October marked the onset of what the Russians call Rasputitsa, a time in which rain and poor drainage turns roads into quagmires slowing tracked and wheeled vehicles to a crawl. While Soviet forces on the battleline fought to slow the German advance, the Soviets put civilians to work helping to build a defense in depth which would stall and ultimately defeat the Germans. Meanwhile, the Soviets shifted troops from Siberia to Moscow where they formed a fully mobilized reserve force.

Regular contributor Victor Kamenir gives a detailed narrative of Operation Typhoon in his article, “Race to Moscow,” capturing both the strategic moves of the generals and the valor of the front-line soldiers. For the Germans, it was a chance to achieve victory in the short-term, whereas the Soviets were fighting for time. If they could stall the German offensive, they would deny the Germans the quick victory they so desperately sought.

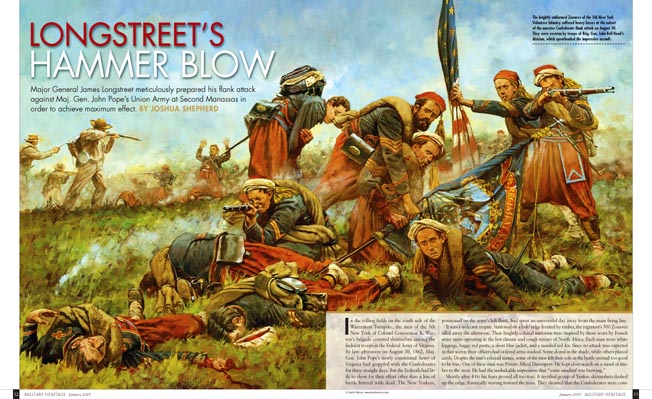

The January 2019 issue also includes a feature article by regular contributor Joshua Shepherd on Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s sledgehammer attack of August 30, 1862, in the Second Battle of Manassas. The reliable commander meticulously prepared his flank attack against Maj. Gen. John Pope’s newly established Army of Virginia Union Army in order to inflict maximum loss on the pompous Union commander’s forces. Shepherd tells how Pope managed to cobble together a rearguard on Henry Hill with elements of Brig. Gen. John Reynolds’ division to keep the Rebels at bay long enough for the Union army to withdraw safely over the narrow Stone Bridge across Bull Run.

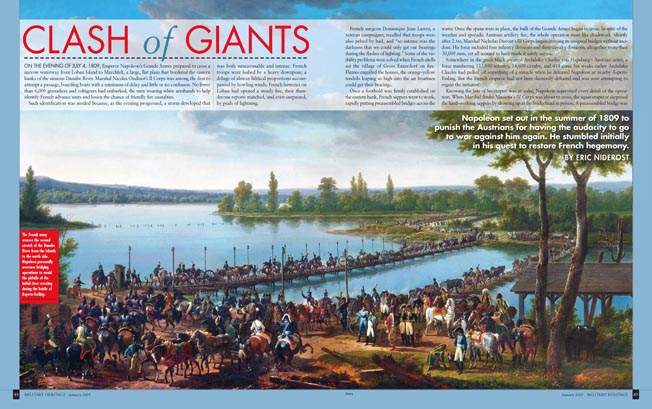

Prolific contributor Eric Niderost offers a compelling account of Napoleon’s bloody victory at Wagram in July 1809 against a resurgent Austrian army led by Archduke Charles. Niderost describes in great detail Napoleon’s meticulous planning of the battle. Niderost explains that the grand clash was a pyrrhic victory given the heavy casualties suffered. A highlight of the article is Napoleon’s creation of a gigantic hollow square composed of 8,000 troops to assault the Austrian center during the climax of the battle.

A medieval warfare article included in the issue is John Spindler’s account of the famous clash at Lake Peipus between the Teutonic Knights and Alexander Nevsky’s Novgorodian army. The Teutonic Knights had hoped to expand into Russia, but Nevsky was a gifted tactical commander who deployed his army in a strong position behind frozen banks of snow and ice to receive the headlong charge of the crusader heavy cavalry. Nevsky’s secret weapon was a contingent of horse archers who rained death on the hapless crusaders softening them up for a counterattack by infantry wielding spears and axes.

Editor William E. Welsh makes a feature contribution to the issue about Spain’s famous admiral Alvaro de Bazan, the Marquis of Santa Cruz. Bazan learned the art of naval warfare from his father who was a famous admiral in his own right. Yet the younger Bazan was to gain greater glory than his father ever achieved. Bazan went toe-to-toe with Ottoman corsairs who sought to control North Africa. His greatest achievement in the Mediterranean occurred at the Battle of Lepanto where he launched a counterattack that saved the Christian fleet. He then went on to secure the Azores from Portuguese rebels for Spain. He is remembered as a master of galley and amphibious warfare.

In the Soldiers Department, Frank Jastrzembski describes the career of Maj. Gen. Edward O.C. Ord who won fame fighting under Ulysses S. Grant both at Vicksburg and in the final months of the American Civil War. As for the Weapons Department, William F. Floyd Jr. gives a concise history of the development and use of PT Boats in World War II, focusing heavily on how they were used in the Pacific theater. Lastly, in the Intelligence Department, Kevin Murrow recounts the experiences of German agent Curt Prufer accompanying the Ottoman forces in the Near East in World War I.

The January issue of Military Heritage magazine is on sale now at bookstores and newsstands. Or subscribe to get each issue delivered to your door, or for access to the digital edition that you can download immediately.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments