By Pat McTaggart

Christmas Day 1941 was anything but festive for the commander of German Army Group South’s 11th Army, General Erich von Manstein. He was currently involved in his toughest battle of the war to date. Staring at the maps spread before him, von Manstein followed the arrows that marked the advance of his divisions.

“I want this to be over by New Year’s Day,” he said to his chief of operations, Colonel Theodor Busse. “The Soviet positions on the northern sector are ready to collapse. When that happens, the port will be ours.”

The port von Manstein was referring to was the important Soviet naval base of Sevastopol. Originally founded as Akhtiar (White Cliff) in June 1783 as a naval base for the expanding Russian Empire, the name was changed to Sevastopol by Catherine the Great in February 1784. She also ordered a fortress to be built to protect the port. During the Crimean War the city underwent a siege by British, French, Turkish, and Sardinian troops in 1855-1856, holding off the attackers for 11 months before falling.

Von Manstein had no intention of taking that much time to conquer the fortress.When his 11th Army advanced across the Perekop Peninsula in late September it was met with heavy Soviet resistance before finally breaking through Russian positions guarding the entrance to the Crimea. Once those positions had been breached, von Manstein was able to spread his forces out with part of the army heading to Sevastopol while another part pushed eastward toward the port of Kerch.

By November 17, the entire Crimea was in German hands, save for the area around Sevastopol. Massive forts guarded the northern approaches to the city, and the Germans were able to take them one by one until only a few remained.

Most of the 11th Army was poised to strike Sevastopol. General Erik Hansen’s LIV Army Corps (22nd, 24th, 50th, and 132nd Infantry Divisions) would strike the northern Soviet positions while General Hans von Salmuth’s XXX Army Corps (72nd and the arriving 170th Infantry Divisions and the 1st Romanian Mountain Brigade) would keep the Russians off guard east of the city.

To achieve the concentration of troops von Manstein thought was necessary to take the city, he had stripped Maj. Gen. Hans Graf von Sponeck’s XLII Army Corps of all but one of its divisions. Along with two Romanian infantry brigades, von Sponeck had Maj. Gen. Kurt Himer’s 46th Infantry Division to defend the coastline along the Kerch Peninsula.

On the mainland, the Soviet winter offensive had been in full swing for almost three weeks. Von Manstein knew that this would be his best chance to take Sevastopol before the ramifications of that offensive were felt in his command. He had soundly defeated Lt. Gen. Pavel Ivanovich Batov’s 51st Army when his forces had taken the Crimea during the previous two months. When the Kerch Peninsula was finally evacuated, approximately 50,000 Red Army personnel made their way back across the Kerch Strait, but less than a third of them were able-bodied combat troops. Batov’s army also lost all of its heavy equipment.

Von Manstein believed he had little to fear from the Soviet forces positioned across the Kerch Strait in the Taman Peninsula. He was dead wrong.

Lieutenant General Dmitri Timofeevich Kozlov’s Trans-Caucasus Front, which would become the Caucasus Front on December 30 and the Crimean Front on January 28, had two frontline armies at his disposal and another in reserve. Maj. Gen. Konstantin Fedorovich Baranov’s 47th Army had two mountain and two infantry divisions, and Lt. Gen. Vladimir Nikolaevich L’vov’s 51st Army had one mountain and 10 infantry divisions plus the 12th Rifle Brigade. Colonel Alexsei Nikolaevich Peruvshin’s 44th Army consisted of one mountain and two infantry divisions plus the 56th Tank Brigade and the 126th Tank Battalion. Kozlov also had some arriving infantry and tank units to use as a reserve.

The Soviet high command (Stavka) had already ordered Kozlov to plan a series of amphibious landings on the Kerch Peninsula before von Manstein planned his final assault on Sevastopol. Kozlov and his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Fedor Ivanovich Tolbukhin, had about two weeks to plan the Red Army’s first major amphibious operation. They had little to go on. The Black Sea Fleet had suffered heavy losses during the previous months, and Rear Admiral Sergei Georgievich Gorshkov’s Azov Flotilla was in the same shape. Consequently, the Soviets had to rely on anything that would float, including gunboats, fishing trawlers, transports and self-propelled barges. There were no amphibious landing craft to be found, so Gorshkov would have to use whale boats to ferry troops unloading from the transports to the shore.

A message reached von Manstein’s headquarters late on Christmas night. It stated that Soviet forces had been observed in the Kerch Strait, but there was no mention of their size. Thinking that the Russians could mount nothing more than minor raids, he was confident that von Sponeck could handle the situation.

The Soviets began landing in force in the early hours of December 26. North of Kerch elements of the 51st Army’s 224th Rifle Division landed at Capes Khroni, Tarhan, and Zyuk and Bulganak Bay. Due to rough seas and winds of 17 to 21 knots, the landings went anything but smoothly.

The II/Rifle Regiment, 160/224th Rifle Division was slated to land at Cape Khroni. About 700 troops were ashore by 0630, but the battalion had lost several troops due to hypothermia or drowning. German troops stationed north of Kerch were surprisingly unresponsive to the landing, and the Soviets were able to put a second battalion ashore along with a platoon of light tanks and some light artillery in the next few hours.

At Cape Tarhan the landing was a disaster with only 18 of the 1,000 men deployed reaching the beach. The Cape Zyuk landing went the same way. Only 290 men of the landing force made it ashore.

Soviet forces landing at Bulganak Bay were in a little better shape. Along with the approximately 1,450 soldiers that made it to the beach, the Russians were able to land a pair of 70mm howitzers, two 45mm antitank guns, and three light tanks.

Although the German forces stationed on the northern coastline offered little resistance to the landings, the Soviet incursions had been reported to higher headquarters. By midmorning the Luftwaffe had arrived over the landing sites. Targeting the ships off the beaches, they bombed and strafed several troop-laden vessels. About 450 Red Army soldiers were lost when the cargo ship Voroshilovwas sunk.

About 10 kilometers south of Kerch, elements of the 302nd Rifle Division began landing at about 0500. Alert German sentries reported Soviet vessels approaching the beaches at Kamysh Burun and Eltigen. The alarm was sounded, and two battalions of Colonel Ernst Maisel’s Inf. Rgt. 42/46 I.D. stationed at the towns were in defensive positions within minutes.

At Kamysh Burun, a small part of the landing force made it to the beach and took cover in some buildings near the shore. German fire forced a second wave to retreat. A third wave was able to reinforce the Russians on the beach, but only about 40 percent of the 5,000-man force scheduled to land was now on Crimean soil.

The landing at Eltigen was an unmitigated disaster. As the Soviets waded toward the beaches, the II/IR 42 opened fire. The Red Army soldiers in the surf did not have a chance, and the shore was soon filled with bodies, while others floated lifelessly in the sea.

Himer’s headquarters was located about 25 kilometers east of Kerch. Steady reports of Soviet landings had been pouring into his communications center, but he had no firm intelligence concerning where the main concentration of Russian forces was located. With only the six battalions of Maisel’s 42nd and Colonel Friedrich Schmidt’s 72nd Infantry Regiments available in the eastern part of the peninsula, it would be difficult to defend the entire area. Himer’s third regiment, Lt. Col. Alexander von Bentheim’s 97th, was spread out dozens of kilometers to the west performing security duties.

Contacting the 97th, Himer ordered von Bentheim to move his two nearest battalions, the 1st and 3rd, to the incursion at Zyuk. It would not be an easy move. Rain had turned the few roads in the area into a sticky morass of clinging mud. The artillery battery accompanying Captain Karl Bock’s III/IR 97 had to be manhandled again and again as the guns became stuck. Farther west the II/IR 97, stationed in the port city of Feodosia about 90 kilometers southwest of Kerch, was also ordered to move toward the northeast.

If things were confused at Himer’s headquarters, they were downright impossible to sort out at von Sponeck’s command post, located west of the Parpach Isthmus at Islam-Terek about 110 kilometers west of Kerch. Von Sponeck had just turned 53 and had served as a frontline officer and battalion adjutant in World War I. Wounded three times during the war, he had stayed in the postwar German Army and had commanded the 22nd Infantry Division during the invasion of the Low Countries. His leadership earned him the Knight’s Cross on May 5, 1940.

With the situation still unclear, von Sponeck alerted his two Romanian brigades and ordered them to head east to support Himer. He also contacted von Manstein asking permission to plan for the evacuation of the Kerch Peninsula if the situation warranted it. If necessary, he planned to stop the Soviets at the Parpach Isthmus, which was only about 25 kilometers wide.

Von Manstein would have none of it and ordered von Sponeck to stand his ground. Himer was to clear out the Soviet bridgeheads and prevent future landings. In his memoirs von Manstein wrote, “If the enemy succeeded in establishing a firm footing at Kerch, the upshot would be a second front in the Crimea and an extremely dangerous situation for the entire army as long as Sevastopol remained untaken.”

While remaining firm about von Sponeck holding his positions, von Manstein dispatched the 4th and 5th Romanian Mountain Brigades to Feodosia. He also ordered a regimental group of the 73rd ID to prepare to move east.

The condition of the roads continued to slow the movement of von Bentheim’s forward battalions. Advance elements reached their jump-off positions by late morning on the 26th. By the time the main body of Bock’s III/IR 97 was starting to deploy, it was already past noon. Bock was unaware that the fragile Zyuk bridgehead had received reinforcements in the form of a battalion from the 83rd Naval Brigade and some T-26 light tanks.

As the Germans deployed, the Soviets launched a spoiling attack supported by three tanks. The Germans were forced back for a time, but a 37mm antitank gun was rushed forward. Commanded by Corporal Max Freyberger, the gun managed to disable or destroy the tanks, stopping the Russian momentum. Launching a counterattack, Bock’s men managed to push the Soviets back to their original positions, but he could go no farther. The attack to destroy the bridgehead had to be postponed until the following day.

During the night the I/IR 97 arrived along with two 105mm howitzers. With temperatures plummeting, the two battalion commanders worked out their battle plan. While infantry, supported by the howitzers, attacked from the southwest, an engineer company would put up a blocking position east of the beachhead. Luftwaffe support was also promised.

The attack began in freezing weather shortly after dawn. With artillery fire hitting the Soviet positions, the German assault forces moved forward. Russian fire slowed the advance, but the appearance of some Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers from Major Clemens Graf on Schöborn-Wiesentheid’s Sturzkampf Gesch-wader (St.G—Stuka Wing) 77 soon silenced the stronger Soviet positions. After the dive bombers left, a half dozen Heinkel He-111 bombers followed up, dropping their lethal packages directly on the beachhead. By late afternoon the Soviet position was taken. At the cost of about 40 killed and wounded, the Germans had killed nearly 300 Russians and had taken another 458 prisoners.

At Cape Khroni the two battalions of Schmidt’s IR 72 were also able to destroy the Soviet bridgehead. All that remained of the Russian assault forces were pockets at Bulganak Bay and Kamysh Burun. Those forces were surrounded, and Himer and von Sponeck planned to deal with them the following day. That plan fell apart during the early hours of December 29.

Soviet troops had been loading on ships in Taman Peninsula ports since the afternoon of December 28. The wind had subsided somewhat, allowing the advance elements of a new invasion fleet to weigh anchor by dusk. Crammed aboard the light cruiser Krasny Kavkaz,the destroyers Nyezamozknik, Shaumyan,and Zhelezniakov,and a host of smaller vessels, the Red Army soldiers endured the elements on open decks as the force moved toward its objective: Feodosia.

All seemed calm in the city as the assault convoy approached the port. With the departure of the II/IR 97, the garrison had been reduced to a skeleton force. The coastal defenses consisted of two artillery battalions (II/AR 54 and I/AR 77) that had a combined total of six Czech-made 150mm howitzers, four World War I-era 100mm howitzers, and 11 World War I-era 150mm howitzers. Also in the area were the lightly armed engineers of Lt. Col. Hans von Ahlfen’s Engineer Staff (for special purposes) 617 comprising 700-800 men.

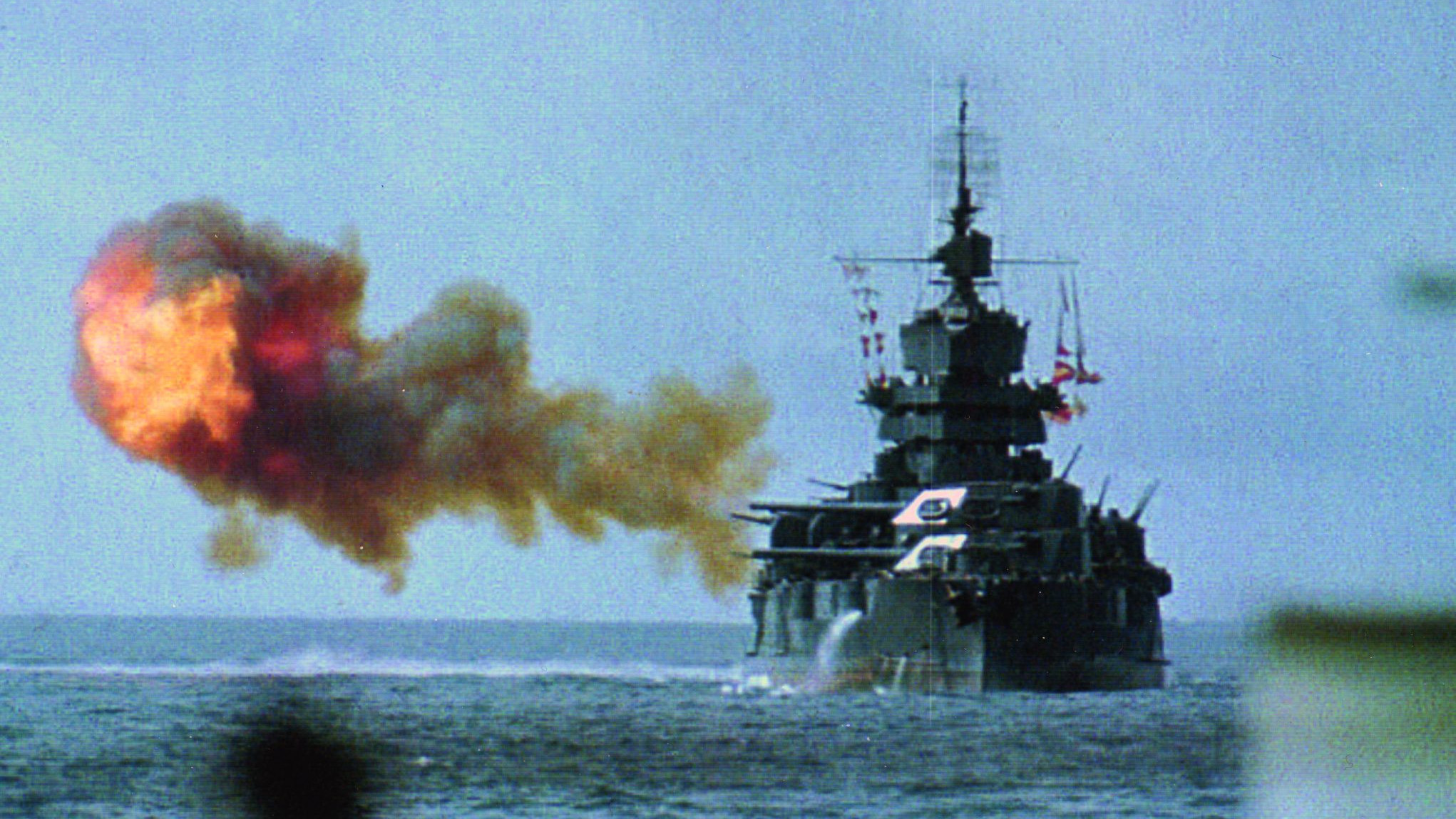

The darkness in the port was broken at 0350 on the 29th as the Soviet ships fired their first star shells. With enemy targets now identified, the Russian warships opened fire with a barrage that lasted about 15 minutes. On the heels of the bombardment, a naval infantry force landed on the harbor mole and captured its lighthouse.

Startled German forces began responding, but the fire was ragged. More naval infantry arrived as the Soviet destroyers pulled alongside the mole and disgorged their passengers. At 0500 the Krasny Kavkazarrived at the mole. More than 1,850 men from the 633rd Rifle Regiment of Colonel Dmitrii Semenovich Kuropatenko’s 157th Rifle Division poured off the deck, adding to the needed numbers to take the town.

As the first light of dawn appeared, German gunners were finally able to properly identify targets, and the Krasny Kavkazmade a good one. Although the ship was hit 17 times, Captain 1st Rank Aleksei M. Guscin gave as good as he got. Several enemy machine-gun and artillery positions were destroyed by the cruiser’s 180mm guns. Under the cover of Guscin’s fire, more Soviet ships unloaded troops, vehicles, and artillery, and by 1000 hours the Germans were forced to abandon the port and most of the town.

Von Sponeck was being kept apprised of the situation, and he realized that the Soviet landing posed a grave threat to the troops on the Kerch Peninsula. He had no troops available to stop the Russians from forming a line across the Parpach Isthmus, trapping Himer and threatening the rear of the German forces besieging Sevastopol. There were already 4,500 Soviet troops in Feodosia by noon, and more were pouring in every hour. Although the Luftwaffe made a brief appearance, the landings were not seriously disrupted. By evening, elements of three rifle divisions had come ashore.

In a telephone conversation with von Manstein, von Sponeck again requested that Himer’s division be allowed to withdraw to the Parpach Isthmus, but the request was firmly denied. Von Sponeck had already ordered Brig. Gen. Cornelius Teodorini’s 8th Romanina Cavalry Brigade to do an about face and return to Feodosia, while Brig. Gen. Gheorghe Manoliu’s 4th Romanian Mountain Brigade was moved forward to prevent the Soviets from breaking out of the city to the west.

While ordering von Sponeck to hold his positions, von Manstein promised to send Brig. Gen. Erwin Sander’s 170th Infantry Division and a combat group of the 73rd Infantry Division under Lt. Col. Otto Hitzfeld to wrest Feodosia from the Russians. Von Sponeck was dubious. He then took matters into his own hands. After notifying 11th Army headquarters that he was evacuating the Kerch Peninsula, he severed all communications with von Manstein.

In his memoirs von Manstein wrote, “We were notified by radio that Count Sponeck had ordered the immediate evacuation of the peninsula because of the new landing at Feodosia. Though we immediately issued a countermand, it was never picked up by XLII Corps signal. While fully appreciating the corps anxiety not to be cut off by the enemy at Feodosia, we didn’t believe that the situation would in any way be improved by a headlong withdrawal.”

At 0830 on December 30, Himer ordered his dispersed regiments to begin a forced march to the west. At the same time the Romanians were ordered to launch an attack on the Soviet forces at Feodosia. The average Romanian soldier was brave, but he had poor leadership and outdated weapons. When the order to attack came the brigades had just finished a grueling march in freezing weather. They were led forward without artillery support, faltered, and then were driven back by a Russian counterattack that pushed the Feodosia bridgehead farther out to the north and west with some Soviet armor getting as far as the outskirts of Stary Krim, about 25 kilometers west of Feodosia.

Meanwhile, Himer’s troops trekked westward throughout the 30th and 31st in a snowstorm and temperatures below zero. Some faced a march of more than 120 kilometers. By the time the forward elements of Himer’s division reached Vladislavovka, located almost in the center of the Parpach Isthmus, they found the town occupied by L’vov’s 63rd Mountain Division. With the division’s heavy weapons far to the rear, there was no choice but to bypass the town and march across the snow-covered fields to the north.

As Soviet reconnaissance patrols probed the German line on the Kerch Peninsula, they reported the enemy withdrawal. The Kerch Strait was now mostly frozen due to the sub-zero temperatures, and troops could be brought over by foot and by vehicle. As soon as units arrived on the peninsula, they were sent piecemeal to the west in pursuit of the Germans. While Himer’s division was pulling into the area just west of Parpach, the Red Army was taking back the Kerch Peninsula, including the port of Kerch, which was taken by the men of Colonel Mikhail Konstantinovich Zubkov’s 302nd Rifle Division.

The arriving elements of the 46th Infantry Division immediately began digging new positions. With the arrival of Group Hitzfeld, a tenuous line was formed about 20 kilometers west of Feodosia with Manolius’s mountain brigade dug in around Stary Krim and the German units manning positions to the north. The Soviets were not long in testing those positions.

A combined infantry-tank attack hit Hitzfeld’s group, which was supported by four assault guns from Assault Gun Detachment 197. The assault guns waited patiently as the 16 T-26 tanks that were supporting the Soviet infantry approached. “Open fire at 500 meters,” came the command.

It seemed an eternity, but the Soviet tanks were finally at the specified distance. As one, the four assault guns spat fire. Hit after hit left 16 blazing wrecks on the battlefield, and the Russian infantry retreated in disorder.

It is only speculation to consider the possibility that a coordinated attack by the 44th and 51st Armies that were now in the Kerch Peninsula could have broken the German line in the first days of 1942, but von Manstein commented on it in his memoirs, writing, “Had the Soviet commander [L’vov] pressed home his advantage properly by pursuing 46th Division really hard from Kerch and thrusting relentlessly after the Romanians fell back from Feodosia, the fate of the entire 11th Army would have been at stake. As it happened, he did not know when to take time by the forelock. Either he did not realize what a chance he had, or else he did not venture to seize it.”

Von Manstein was forced to call off his assault on Sevastopol because of the developments. He left enough units to keep the fortress surrounded and then ordered Brig. Gen. Maximilian Fretter-Pico, who had replaced von Salmuth in late December, to move his XXX Corps east to bolster the Parpach defenses and to prepare for an assault to take back Feodosia.

Now it was time for von Sponeck to pay the piper. In severing communications with the 11th Army and intentionally disobeying a direct order from von Manstein, he had done something that was unthinkable at the time in Hitler’s Wehrmacht. Von Manstein relieved him on New Year’s Eve, replacing him with General Franz Mattenklott.

On his return to Berlin, von Sponeck stood before a court martial presided over by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring. The court’s sentence was reduction to the ranks, forfeiture of all orders and decorations, and death, which was later commuted to seven years’ fortress detention. He languished in prison until July 23, 1944, when he was executed by an SS firing squad during the aftermath of the July 20 assassination attempt on Hitler.

Himer’s 46th Infantry Division also received a startling sentence of sorts. Early in January the division’s regimental commanders were ordered to report to 46th headquarters where an emotional Himer read a message from the new commander of Army Group South, Field Marshal Walter von Reichenau. It stated, “Because of its slack reaction to the Russian landing on the Kerch Peninsula, as well as its precipitate withdrawal from the Peninsula, I hereby declare 46th Division forfeit of its soldierly honor. Decorations and promotions are in abeyance until countermanded.”

After marching across the peninsula on orders of the corps commander and then stopping the Soviets at Parpach, the officers were too stunned to reply to the slap in the face that von Reichenau had given them. However, the loss of honor for the division did not last long. On January 15, von Reichenau suffered a stroke. He was replaced by Field Marshal Fedor von Bock, who issued the following order of the day toward the end of the month: “For its outstanding performance in the defensive fighting in the isthmus since the beginning of January, I express my very special commendation to the 46th Division and shall be looking forward to recommendations for promotions and decorations.”

While the 46th occupied positions on the northern sector of the isthmus, Fretter-Pico prepared his two divisions for an attack to retake Feodosia. Peruvshin had enlarged his bridgehead, but in doing so he could not focus his forces on one central point of attack. His 236th Rifle Division (Maj. Gen. Vasilii Konstantinovich Morzov) occupied a line facing the Germans about 14 kilometers north of Feodosia. The two other divisions inside the bridgehead were spread out on either side of Morzov’s division.

Besides the two divisions from his XXX Corps (Brig. Gen. Fritz Lindemann’s 132nd and Brig. Gen. Erwin Sander’s 170th), Fretter-Pico had Group Hitzfeld, two battalions from Himer’s 46th, three assault guns from Major Gerhard, and a few assault guns from Major Heinz Steinwach’s Assault Gun Detachment 197. Along with additional assault guns and Romanian troops, these units moved into positions to effectively stem any enlargement of the bridgehead to the north and west.

Peruvshin seemed content to wait for more reinforcements and for the arrival of L’vov’s 51st Army at Parpach before he made his next move. On January 5, the 46th reported that advance elements of L’vov’s army had arrived, but the main units of his divisions were still coming forward. The artillery elements of the 51st were even farther back on the peninsula and would take days to travel over the frozen ground to reach Parpach.

The Germans were able to strike first. On January 15, artillery fire hit Morzov’s forward positions. About five kilometers behind these positions, the main elements of the 236th Rifle Division were entrenched along a ridgeline. While the German artillery pounded the forward positions, Luftwaffe aircraft appeared and dropped their deadly ordnance along the ridge, severing communications and generally creating havoc.

At 0600 the order came, “Aufmarsch—zum Angriff! (“Deploy—to the attack).” Group Hitzfeld, supported by Himer’s I/IR 42 and II/IR 42, advanced quickly. The dazed Russians in the forward positions stood no chance against the Germans. At the village of Novopokrovka, a pair of T-26 light tanks tried to stop the enemy advance. They were knocked out by a section of guns from Assault Gun Detachment 190. The section, commanded by 1st Lt. Cardeno, continued to advance, but it soon came under direct fire from a 76.2mm gun battery. One assault gun, commanded by Lieutenant von Harnier, received a direct hit, killing the commander and his gunner. The remaining two assault guns were able to destroy the Russian battery as the German infantry continued to advance.

Peruvshin had been caught by surprise. To make matters worse, his headquarters came under air attack. The general was critically wounded during the bombing. The Russians were still unaware of German intentions, and it was thought that the attack on the 236th Rifle Division might be a feint to obscure a German attempt to take the village of Vladyslavivka. Therefore, instead of moving forces to assist Soviet units at Feodosia, both the 44th and 51st Armies sent units to reinforce the Vladyslavivka sector.

The bombing of the ridgeline, coupled with the Germans’ lightning attack, made it possible for Hitzfeld’s men to secure Morozov’s main line, giving them a perfect observation point that allowed most of the Soviets’ positions to be seen. As the troops settled in for the night, Hitzfeld was already planning his next move.

“We knew that we had them,” Hitzfeld wrote in 1983. “My observers could call in artillery fire on the Russian positions, and the 132nd was already on the move on our right flank. My men would keep the Russians to our front busy while the 132nd would drive on Feodosia.”

On the 16th, the infantry moved forward again. To Hitzfeld’s left the two battalions of the 46th headed toward the heights southwest of Vladslavivka. They were supported by two assault guns under the command of Lt. Damman. The two guns stumbled into an assembly area for Russian tanks and infantry. Supported by some of the German infantry, Damman ordered his guns to attack the unprepared enemy. Tank crews were mowed down by rifle and machine-gun fire before they could react, and Damman’s gunfire destroyed tank after tank. When the cease-fire was given, 16 T-26s were smoldering wrecks. An antitank gun and several mortars and machine guns were also destroyed.

Lindemann’s 132nd moved forward on the 17th, driving into the northern sector of Feodosia. To the right of the 132nd, Sander’s 170th Infantry Division also made good progress. On the following day, Major Franz Griesbach’s IR 170/170 ID reached the center of the city followed by other units that flushed out the remaining survivors. The Soviets had fought desperately, but they could not stop the German juggernaut. In his memoirs von Manstein wrote that the Soviets had lost 6,700 killed with 177 guns and 85 tanks destroyed. German casualties from XXX Corps numbered 243 dead or missing and 752 wounded.

With the capture of Feodosia complete, Fretter-Pico continued to attack the remaining two divisions of the 44th Army. In the north, XLII Corps joined in, catching L’vov’s force off guard and pushing it back 22 kilometers. By the end of the 20th, the two German corps had advanced to the narrowest part of the Parpach Isthmus, but they did not have the strength or the supplies to go any farther. As the Germans dug in, the Russians did the same. The 20-kilometer-wide Parpach Narrows soon resembled a scene from the Western Front in World War I as both sides strengthened their positions with outposts and barbed wire.

Although Soviet reinforcements continued to flow across the Kerch Strait, the Russians were unable to make any headway against the German positions. Besides having logistical problems, Kozlov, who had just been named commander of the newly created Crimean Front, had to deal with Corps Commissar Lev Zakharovich Mekhlis. Mekhlis’s job at the front headquarters was to make sure that the Crimea would be liberated.

A close cohort of Stalin, Mekhlis was known for his ruthlessness. He had been actively involved in the army purges of the 1930s, and he had ordered the execution of the commander of the 44th Rifle Division during the early disasters of the Winter War against Finland.

Mekhlis was constantly at odds with Kozlov. With no military background, he demanded that arriving reinforcements attack the Germans as soon as they arrived at the Parpach Line. His inane orders cost the Soviets thousands of lives from late January to the end of February and gained nothing.

Notwithstanding those losses, Mekhlis, on orders from Moscow, forced Kozlov to launch four offensives between February 27 and March 11. The first offensive began with an artillery barrage from more than 200 guns. The attack was aimed at Mattenklott’s XLII Corps, anchored in the north by positions on the Sivash, a vast salty marsh. L’vov’s 51st Army used five divisions in the attack. Although the initial armor-supported attack succeeded in driving back the 18th Infantry Regiment of Brig. Gen. Nicolae Costeacu’s 18th Romanian Infantry Division, which was holding the area on the southern side of the Sivash, Kozlov was unable to commit his heavy armor due to the soft terrain, leaving only his light tanks to support the infantry.

The combined Russian force advanced about 4½ kilometers the first day but was stopped when Mattenklott sent German reinforcements to plug the gap left by the Romanians. Several Soviet tanks were knocked out by German artillery and antitank guns.

On the 28th, Kozlov ordered the 77th Rifle Division of Maj. Gen. Konstantin Stepanovich Kolganov’s 47th Army, which was held in reserve in the eastern Kerch Peninsula, to enter the fray. The 77th did succeed in bending Mattenklott’s left flank, but the German line did not break.

A frustrated Kozlov moved his attack farther south, going up against a German strongpoint at the small village of Koi-Asan. Four tank brigades and a tank battalion, supported by two infantry divisions, were committed to the attack. They ran into a wall of fire from German antitank guns. The defenders were supported by Captain Helmut Bode’s III/StG 77, which fell upon the Soviet armor like hawks on field mice. By the end of the day, the Russians had lost at least 90 tanks, forcing Kozlov to call off the offensive.

A furious Stalin ordered another offensive to begin within 10 days—barely enough time for Kozlov to make good his losses. Mekhlis blamed Kozlov’s chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Fedor Ivanovich Tolbukhin, who would later rise to the rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union, for the failed offensive. He was relieved on March 10 and replaced by Maj. Gen. Petr Pantelimonovich Vechnyi, who had accompanied Mekhlis from Moscow.

Kozlov opened his next offensive at 0900 on March 13. Once again, Koi-Asan, which the Germans had reinforced with an extensive minefield and more antitank guns, was the main target. A force of three rifle divisions from the 51st Army took part in the assault. They were supported by more than 200 tanks that were spread out piecemeal among the infantry as a reserve on Mekhlis’s orders.

After three days of failure, Mekhlis ordered Kozlov to commit his armor. Churning up mud as they crossed the soggy ground, the tanks were met by antitank fire and the assault guns of 1/Assault Gun Detachment 197 and 2/Assault Gun Detachment 249. Lieutenant Johann Spielmann described the action in a 1987 letter to the author: “We had excellent cover, and we waited until the slow-moving Russian tanks were at mid-range. My section fired again and again, making several hits. We destroyed 14 tanks in two days, mostly T-34s. It was like shooting on the practice range.”

In all, the Russians lost 157 tanks to antitank guns and assault gun fire. The battle raged until March 20, when Kozlov was once again forced to admit failure and withdraw his battered forces. A third offensive began on March 26 and suffered a similar fate.

Both sides had received reinforcements before the fourth offensive began on April 9. Kozlov once again received more infantry and tanks, and on the German side Maj. Gen. Johann Sinnhuber’s 28th Light Division was moved into the Parpach Line.

When the Soviets began their offensive early on April 9, Koi-Asan was again the main objective. The assault ran into trouble from the start. Several tanks were destroyed by a new antitank weapon, the 28mm tapered bore gun, which had a low silhouette. A corporal in the 28th, Emanuel Czernik, was able to destroy seven T-26s and an armored car on the first day using the weapon. After days of fighting, the Soviets once again withdrew.

The first four months of 1942 had ended with catastrophic losses for the Soviets in the Crimea. Between Kerch and Sevastopol, the Russians lost 352,000 killed, wounded, or captured. Most of those casualties were suffered trying to break the German line at Parpach. In comparison, von Manstein lost a little over 24,000 killed, wounded, or missing.

With Hitler planning his summer offensive to take Stalingrad, it became imperative that Sevastopol be taken as soon as possible. Von Manstein realized that this would not be possible with his rear still threatened by the three Soviet armies occupying Kerch. Therefore, even while the battles for Parpach raged his staff was working on a plan to destroy the enemy in the Kerch Peninsula. It was codenamed Unterneh-men Trappenjagd (Operation Bustard Hunt).

The German and Romanian forces designated for the operation would be outnumbered by more than two to one. Although the Russians had suffered horrendous casualties during the previous months, Kozlov could still field 17 infantry divisions, two cavalry divisions, three rifle brigades, and four tank brigades in the Kerch Peninsula.

The main Soviet defensive line lay in front of a 10-meter-wide, five-meter-deep antitank ditch that ran across the width of the approximately 20-kilometer-wide Parpach Isthmus. East of the ditch, a second defensive line known as the Nasyr Line was constructed as a fallback point in the event the Germans breached the Parpach position. A final position, the Sultanovka Line, was built about 40 kilometers east of the Nasyr Line.

In the air, Kozlov would count on a force of 176 fighters and 225 bombers from Maj. Gen. Evgenii Makarovich Nikolaenko’s Air Forces Crimean Front. Unfortunately, many of those aircraft were obsolete and were clearly outclassed by German models. Nikolaenko was also short of reliable reconnaissance aircraft—something that would play right into von Manstein’s plan.

Since the left flank of the Russian line, anchored by the Black Sea, was marsh-filled terrain, Kozlov expected any possible German assault to take place on his right in the 51st Army sector. Therefore, he strengthened L’vov’s force, bringing a total of eight rifle divisions, three rifle brigades, and two tank brigades to man the approximately nine-kilometer front.

Defending the left, the 44th Army, now commanded by Lt. Gen. Stepan Ivanovich Cherniak, had five rifle divisions and two tank units. Kozlov placed more tank and cavalry units behind the main line to use as a mobile reserve. Kolganov’s 47th Army was in position farther east with four rifle divisions and a cavalry division.

Trappenjagd was reminiscent of von Manstein’s plan to drive through the Ardennes in 1940. Once again he planned to use terrain as an ally. He ordered Mattenklott’s XXX Corps (46th and 50th Infantry Divisions) and General Florea Mitranescu’s VII Romanian Corps (10 and 19th Romanian Infantry Divisions and 8th Romanian Cavalry Brigade) to fake preparations for an all-out attack on the 51st Army, which fit with Kozlov’s assessment of where the main thrust would fall.

While Kozlov kept his eyes to the north, von Manstein planned to use Fretter-Pico’s XXX Corps to drive through the marshland and hit Cherniak’s army with the 132nd and 170th Infantry Divisons, the 28th Light Division, and a motorized group commanded by Colonel Karl von Groddeck. Brig. Gen. Wilhelm von Apell’s 22nd Panzer Division, which had recently arrived in the Crimea, would be held in reserve to exploit the breakthrough. Also included in the plan was an amphibious landing behind the Russian frontline positions to further disorganize the Soviets.

Von Manstein’s trump card was the Luftwaffe. While German fighters destroyed or kept Russian reconnaissance aircraft from flying over German lines, the commander of the VIII Fliegerkorps (Air Corps), General Wolfram von Richthofen, set up his headquarters in the village of Klyuchoye, about nine kilometers west of Feodosia, on May 1. During the next week the Luftwaffe presence in the Crimea swelled to a total of 555 combat aircraft, which were scattered in airfields around von Richthofen’s headquarters. When Trappenjagd was ready to begin, elements of Jägdgeschwader (Fighter Wing) 52 and 77 and Kampfgeschwader (Bomber Wing) 26, 27, 51, 76, and 100 would be available. There would also be two groups from Schlachgeschwader (SchG.-Ground Attack Wing) 1 and all of von Schönborn-Wiesenthied’s StG 77 participating in the air assault.

The forces under von Richthofen performed double duties once they reached the Crimea. To gain air superiority, Russian airfields on the peninsula became the objects of bombing and fighter attacks. In one such attack on May 2, German escort fighters shot down 32 Soviet planes without a single loss while the accompanying bombers destroyed several more on the ground.

Von Richthofen was also tasked with interdicting the Soviet supply line to Kerch. Since it would be next to impossible to keep a constant air presence over the narrow Kerch Strait, he concentrated his bombers on the key ports of Kerch and Kamysk-Burun on the east coast of the Crimea and Novorossiysk and Tupase on the Taman Peninsula. Because of the damaged port facilities, supplies to Kozlov’s armies slowed to a trickle. The bombers also further weakened Kozlov’s forces by hitting targets on Kerch that included fuel and ammunition dumps, artillery and antiaircraft positions, and infantry installations and troop concentrations.

Just before dawn on May 8, the German artillery opened up accompanied by rockets, heavy howitzers, and von Richthofen’s antiaircraft guns, which could also be used for direct fire missions. Soviet positions disappeared as the fire crept forward. The barrage on the forward enemy defenses lasted 10 minutes, after which the German infantry surged toward the positions of Cherniak’s 63rd Mountain Rifle Division and the 276th Rifle Division, which held a 61/2-kilometer stretch of the Russian line. Bombers flew overhead and shattered the bunkers and gun emplacements in the main defensive line.

German fighters ruled the air over Kerch and the Kerch Strait, shooting down more than 80 enemy aircraft that rose to challenge them. The Russians were able to shoot down 10 German planes and damage 10 more, but they essentially lost control of the sky by the end of the first day.

As Stukas from StG 77 pounded a strongly fortified position known as the “Tartar Hill,” the Silesians of the 28th Light Division, supported by 21 assault guns, moved around the hill and struck the 63rd Mountain Rifle Division’s 346th Rifle Regiment, virtually destroying it. The now isolated 251st Rifle Regiment, which was holding the hill, was soon overwhelmed and also destroyed.

The third regiment of the 63rd, the 291st, met the same fate at the hands of the Bavarians from Lindemann’s 132nd. Surviving remnants of the 63rd were soon streaming east toward the main defense line, which was held by the 157th and 404th Rifle Divisions on the western edge of the antitank ditch. Although Cherniak had his armored reserve (56th Tank Brigade and 126th Tank Battalion) stationed around Arma Eli, about 15 kilometers to the rear, he did not order it forward at this critical time.

Lindemann’s IR 438 and Sinnhuber’s Jäger Regiment 49 pushed through the Soviet main defense line and reached the western side of the antitank ditch before 0600. Less than two hours later the 49th had secured a bridgehead on the eastern side. An attack by the 126th Tank Battalion, which had finally moved forward, was beaten back by the 190th Assault Gun Detachment with the loss of only one German gun for 24 destroyed Soviet tanks.

North of Sinnhuber, Brig. Gen. Friedrich Schmidt’s 50th Infantry Division had harder going against the 276th Rifle Division. The marshy ground and muddy roads made movement difficult, and it took most of the day to push the 276th back to the antitank ditch. Lieutenant Spielmann, who had taken command of the 1/Assault Gun Detachment 197 after its commander, 1st Lt. Liedkte, had been wounded, recalled the opening assault: “The condition of the roads slowed our advance and the battery also encountered a series of antitank obstacles that had to be removed by our pioneers [engineers]. Even with these difficulties my guns were able to hit several Russian positions, allowing our infantry to push forward.”

Cherniak’s army was in turmoil. To add to the confused situation, von Manstein’s surprise amphibious assault began shortly after the main attack had started. An infantry company and a platoon of engineers were ferried by assault boats of Sturmboote-Kommando 902 from Feodosia to a point about 1,300 meters behind the vaunted antitank ditch. After enemy coastal defenses were destroyed in the surprise assault, reinforcements were landed during the course of the day under the protection of the Luftwaffe. By midafternoon most of Lindemann’s IR 436 was ashore and bearing down on the rear of the 157th and 404th Rifle Divisions.

With the successful amphibious landing, von Manstein unleashed Group Groddeck. The colonel commanded a combined force of German and Romanian troops that contained approximately five infantry battalions, a Romanian cavalry regiment, elements of three assault gun battalions, some captured Russian tanks, and a variety of artillery, antiaircraft, antitank, and engineering units. Motor pools from all over the German-held Crimea were stripped bare to provide the needed mobility for the infantry.

Cherniak was finally alarmed enough to commit his remaining armor (the 56th Brigade and remnants of the 126th Battalion) to try and check the advance of the 28th Light Division. German air superiority stopped the Russians cold. StG-77 Stukas and Henschel Hs-129 B ground attack aircraft from Lt. Col. Otto Weiss’s SchG 1 caught the Soviet tanks in their assembly areas. With sirens screaming, the Stukas dove on the tanks, dropping their bombs with deadly accuracy. The 20mm and 30mm cannons from the Henschels added to the destruction. In a matter of minutes, 48 of the 98 tanks scheduled to attack were destroyed and the rest retreated north and east in disarray.

Commissar Mekhlis hoped to disassociate himself with the day’s disaster by transmitting a damning condemnation of Kozlov and his military council to the high command in Moscow. He also said that he was the only one who had foreseen the threat of the German attack. The message was shown to Stalin, who shot back with the following reply that Mekhlis surely never expected: “Your code message I received. You hold a strange position that you work there only as a detached observer who is not accountable for the events at the Crimean Front. Your position is sure convenient, yet it is rotten to the core. At the Crimean Front, you are not an outside observer, but the responsible representative of Stavka, who is accountable for every success and failure that takes place at the Front, and who is required to correct, right then and there, any mistake made by military officers.

“You, along with the military officers, will answer for never reinforcing the weakness of the left flank of the Front. If everything seems to indicate that the opponent will begin an advance the first thing in the morning, yet you haven’t done everything needed to repel their advance, because you limited your involvement to only passive criticisms, then you will make things worse for yourself. So it seems that you still have not figured out that we sent you to the Crimean Front not as a government auditor but as a responsible representative of Stavka.

“You demand that we replace Kozlov with anyone else, even with Hindenburg. Yet it is impossible for you to be unaware that Soviet reserves do not have anyone named Hindenburg. The situation is not complicated, and you could have taken care of it all with what you had all by yourself…. You do not need to be a ‘Hindenburg’ to grasp such a simple thing, while sitting for two months at the Crimean Front.”

While the back and forth between Stalin and Mekhlis was taking place, the German assault continued. Although engineers at the antitank ditch had blasted the steep walls of the ditch with explosives, the crossing points were still narrow and soft. The engineers would have to work harder on them to allow the passage of the 22nd Panzer’s tanks, but von Groddeck’s lighter forces were able to traverse the obstacle with few problems.

By noon on the 9th, von Groddeck had raced past the advancing units of the 132nd Infantry Division and had sliced through the Nasyr Line. The Soviets were mostly unaware of the German units that had advanced almost 25 kilometers in just a few hours.

Although the bulk of Kozlov’s divisions were on the Soviet right flank with the 51st Army, the Russian units there remained stagnant. One of the reasons for this was that a bombing raid had taken out the 51st Army headquarters and had killed L’vov, cutting communications with the Crimean Front headquarters at a critical moment.

As Group Groddeck approached the Sultanovka Line, the two Soviet divisions occupying the position (11th NKVD and the vastly understrength 72nd Cavalry of the 47th Army) were blissfully ignorant of its presence. The first indication of trouble was when elements of von Groddeck’s group hit the Marfivka airfield, about 35 kilometers southwest of Kerch. The airfield’s defenses were overwhelmed almost immediately, and in a few minutes 35 I-153 biplane fighter-bombers were burning on the ground.

While von Groddeck’s forces raised havoc in the Soviet rear, the 22nd Panzer had finally made it across the antitank ditch. However, instead of making a lightning run to the north to cut off the 51st Army the divison became bogged down as a weather front came through accompanied by heavy rain.

Although Group Groddeck had performed splendidly, von Manstein was concerned about the slow progress being made by the 22nd. “Everything was going too slowly for the army commander,’ von Richthofen wrote later. “In my opinion he was worried. I calmed him down and pointed to our decisive actions planned for the next few hours. He remained skeptical.”

Throughout the fog-shrouded night the 22nd Panzer struggled forward. The rain stopped early on the 10th, making movement easier as the sun began to dry the ground. A panicked Kozlov launched his last armored reserves (40th Tank Brigade and 229th Tank Battalion) in a desperate effort to halt General Wilhelm von Apell’s progress. Once again the Luftwaffe rose to the challenge, and the Soviet armor was decimated. Around noon on the 10th, the 22nd was nearing the Sea of Azov, followed by the 28th Light and elements of the 170th and 50th Infantry Divisions.

A heavy artillery barrage caused the Germans multiple casualties, but the Russian guns were soon silenced by the Luftwaffe, led by von Richthofen himself, who directed the bombing from the cockpit of his Feiseler Storch observation aircraft. In his diary for the 10th he wrote, “By sunset we have isolated 10 Red divisions, except for a narrow gap. In the morning the extermination can begin.”

Morning fog once again hampered closing the pocket on the 11th, but by 1100 hours visibility had improved. Von Manstein ordered the XLII Army Corps and the VII Romanian Army Corps to attack from the west, putting further pressure on the 51st Army. Overhead, von Richthofen’s squadrons blasted the Soviet units holding open the gap at Ak-Monai, about 65 kilometers west of Kerch. A followup attack by the 22nd Panzer and 132nd Infantry scattered the dazed survivors, and the final escape route of the 51st Army was closed.

The Russian units that had made it through the gap were easy prey for the Luftwaffe as they fled eastward. The ground attack squadrons wreaked incredible destruction as they bombed and strafed the Soviet columns. Von Richthofen, flying over the area in his Storch, initially described it as a “wonderful scene.” As he swept down to where the Russians had defended Ak-Monai, he changed his mind and wrote: “Terrible. Corpse-strewn fields from earlier attacks…. I have seen nothing like it so far in this war.”

Farther east, von Groddeck pushed on toward Kerch with following German infantry heading to the already breached Sultanovka Line. The only Soviet unit in von Groddeck’s path was the 11th NKVD Division, which had been formed at Krasnador in January. Von Groddeck was wounded in an ambush by these troops, but the Russians soon fled in the face of artillery fire and Luftwaffe bombing.

With Soviet command and control completely shattered, the trapped units of the 51st Army began surrendering en masse, freeing up more German forces to drive on Kerch. By April 13, the 132nd and 170th Infantry Divisions had crossed the Sultanovka Line, closely followed by the 22nd Panzer. Even though von Richthofen had just lost command of two bomber groups and a fighter and Stuka group the previous day due to a Russian attack on Kharkov, his remaining aircraft continued to pummel Soviet pockets of resistance.

With German forces approaching Kerch, Kozlov used any troops that were left in the area to prepare positions for a last-ditch defense of the city. Soviet naval forces and small craft braved sporadic German fire to cross the Kerch Strait to evacuate wounded and essential personnel, but it was clear that the majority of the Crimean Front was doomed.

Nevertheless, the Dunkirk-style evacuation continued even as the Germans reached the outskirts of the city. With his diminished air capacity, von Richthofen became increasingly frustrated.

“The Russians are sailing across the narrows in small craft, and we can do nothing about it,” he fumed. “It makes me sick. One isn’t sure whether to cry or curse. The Reds remain massed on the beaches and cross the sea at their leisure. Infantry and tanks can’t advance because of the desperately resisting Reds, and we [the Luftwaffe] can’t do anything because we don’t have adequate forces.”

Kerch finally fell on April 15, but that was not the end of the fighting on the peninsula. Large and small groups of Red Army soldiers continued a fanatical resistance for several days. First Lt. Alfred Dürrwanger, commander of the 10th (heavy weapons) Company of Jäger Regiment 83/28th Light Division, described the fighting in a 1986 letter to the author: “We had never seen such enemy fire up to now. The Ivans were well entrenched in their positions in front of us and seemed to have unlimited ammunition. Several of my men were hit, but the rest of them showed great courage under the enemy fire. I told them that we would charge the first position, and they followed without question. It was better than being shot one by one.”

Dürrwanger led his men forward, surprising the enemy with his audacity. Overcoming the first position, the Germans surged forward, taking another and then another. The assault opened the way for neighboring units to advance and overpower the Soviet defenses. Dürrwanger was wounded in the head during the attack but continued to lead his men until the battle was over. Less than two months later he received the Knight’s Cross for his actions.

“It was for the courage of my men that the award was given,” he wrote. “Since they could not all receive the medal the decision was made to give it to me, but each one of them deserved it.”

The Soviet pockets soon collapsed. In less than two weeks von Manstein had cleared the eastern part of the Crimea. It had cost the XXX and XLII Corps 1,708 dead or missing and 5,885 wounded. A handful of aircraft had been lost, as were nine artillery pieces, three assault guns, and 12 tanks.

In return, three Soviet armies had been decimated. Of the 250,000 Russian troops on the Kerch Peninsula, about 170,000 prisoners had been taken and about 28,000 had been killed. The entire artillery and armored forces of the three armies (1,133 guns and 258 tanks) had either been captured or destroyed. Soviet air losses were place at more than 400.

For their failure, Cherniak, Kolganov, and Nikolaenko were demoted to the rank of colonel, while Kozlov was demoted to major general. Commissar Mekhlis, still sputtering comments about the front commander’s incompetence, was reduced two ranks. It could have been much worse for all of them.

With the eastern Crimea now firmly in German control again, von Manstein was free to continue his assault on Sevastopol. In less than 21/2months, the fortress city fell, yielding another 90,000 prisoners. The Crimea would endure almost two more years of German occupation until it was liberated in May 1944.

Author Pat McTaggart is an expert on World War II on the Eastern Front. He has written extensively for WWII History and resides in Elkader, Iowa.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments