By Pat McTaggart

It was called Nordlicht, or Northern Lights. With Hitler’s drive toward Stalingrad in full swing, the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW—German Armed Forces High Command) was also planning to end the almost year-long siege of Leningrad in a two-pronged attack to capture the city.

Failing to take Leningrad in 1941, Army Group North, now commanded by General Georg von Küchler, had settled into a siege reminiscent of World War I. Long lines of trenches covered the landscape, and fierce artillery barrages heralded attacks from one side or the other that yielded little ground gained or lost but were costly in manpower and equipment.

During the Winter Offensive of 1941-1942, the Russian High Command (Stavka) had attempted to lift the siege with a coordinated attack by the Volkhov Front and the Leningrad Front. The offensive around Leningrad began in early January, but despite outnumbering the Germans 1.5-1 in men, 1.6-1 in guns and mortars, and 1.3-1 in aircraft, initial Soviet successes were rare due to poor command and control. Individual army commanders failed to coordinate operations with neighboring forces, and intense German resistance became an increasing concern.

The fighting continued through the first half of 1942, with the Soviets suffering horrific casualties. Lt. Gen. Andrei Andreevich Vlasov’s 2nd Shock Army, which had penetrated the German line, was surrounded and left to starve to death in a swampy forested area northwest of Myasoni Bor, and the other Soviet forces were fought to a standstill.

It was in this atmosphere that the operation to remove the thorn that was Leningrad was born. On June 30, 1942, Küchler, who was promoted to field marshal the same day, arrived at the Wolfsschanze (Wolf’s Lair), Hitler’s headquarters near Rastenburg in East Prussia. General Franz Halder, chief of the Army’s General staff, recounted the meeting in his diary.

“[Küchler] submits his plans. He envisages four offensives in his sector, which, as they supposedly could be carried out only one after another, would take all of twenty weeks. The individual projects are put up for discussion.”

Küchler’s plan consisted of two actions on the right flank of Army Group North and two actions on the Leningrad Front. The two in the south included widening the northern flanks of the corridor to Demiansk and the elimination of a Soviet salient left over from the Russian winter offensive.

In the Leningrad area, the operations consisted of eliminating the Soviet bridgehead in the vicinity of Oranienbaum southeast of Leningrad and the elimination of the Pogost’e bridgehead on the west bank of the Volkhov River. To assist in the Leningrad operation, especially in the reduction of the mighty island fortress of Kronstadt, which guarded the approaches to the city around the Gulf of Finland, three gigantic siege batteries were to be ordered from the Crimea to the Leningrad front.

Dora was a railway gun that fired an 800mm (31.5-inch) shell. Karl and Gamma were mortars, the former firing a 600mm (24-inch) shell and the latter firing a 419mm (16.5-inch) projectile. All three batteries had taken part in the successful capture of the Sevastopol fortress.

On July 23, a directive from Hitler ordered that Leningrad be captured by the first half of September. The code name for the operation was Fererzauber (Fire Magic), but it was renamed Nordlicht a week later. To help accomplish the operation, newly promoted Field Marshal Erich von Manstein was directed to move his 11th Army headquarters, along with five infantry divisions, from the Crimea to Army Group North. That move, virtually crossing the entire Eastern Front from south to north, would not be completed until late August.

Küchler realized that his army group did not have the resources to conduct the four proposed operations discussed on June 30 plus Nordlicht. Therefore, he lobbied Hitler and the Oberkommandeo des Heeres (OKH, Army High Command), which was subordinate to the OKW, to postpone the Oranienbaum operation until Nordlicht was successful. OKH agreed, and because of the weather and changes in the tactical situation, the operation was postponed and eventually cancelled along with the operation against the Pogost’e salient. The operation to widen the corridor to Demiansk was also postponed.

The Soviets were far from inactive as the Germans prepared for Nordlicht. Lt. Gen. Leonid Aleksandrovich Govorov, commanding the Leningrad Front, was receiving reports that the Germans were concentrating forces around Siniavino and Chudov. Although it was not clear why, it was thought they were gathering for the soon to be cancelled offensive against Red Army units on the west bank of the Volkhov.

Born in 1897, Govorov had been commandant of the Military Artillery Academy before the war and was a graduate of the Frunze and General Staff academies. He had recently replaced Lt. Gen. Mikhail Semenovich Kozin as the commander of the Leningrad Front after the disastrous spring campaign.

With somewhat foggy intelligence reports pointed toward an enemy offensive in the Leningrad area, Govorov planned to disrupt the enemy with preemptive attacks of his own. As a precursor to these attacks, meanwhile, Stavka ordered the devastated 2nd Shock Army to be reformed in mid-July as part of the Volkhov Front. Its new commander, Lt. Gen. Nikolai Kuzmich Klykov, was an energetic no-nonsense general who had previously commanded the 32nd and 52nd Armies.

While the 2nd Shock Army was forming, Govorov ordered Lt. Gen. Ivan Fedorovich Nikolaev to launch attacks to keep the Germans off guard. Divisions of his 42nd Army hit the enemy near Staro-Panovo for four days, beginning July 20. Although the Soviets hoped for success, the attacks were beaten off at a heavy price in Russian blood. Halder’s diary for that period barely mentioned the fighting, and when it did it described it as “minor and of little importance.”

Despite the failure of Nikolaev’s troops to make a dent in the German defenses, Lt. Gen. Vladimir Petrovich Svirdov was ordered to attack enemy positions south of Kolpino with units of his 55th Army. Colonel Semen Ivanovich Donskov’s 268th Rifle Division, supported by the 220th Tank Brigade, hit Brig. Gen. Martin Wandel’s 121st Infantry Division in the Putrolovo area west of Krasny Bor. After a fierce struggle, the Germans were driven out of their fortified positions.

The 4th SS Police Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. of Police Alfred Wünneburg, was soon drawn into the battle. The tenacious Donskov held firm, throwing back several German attacks and counterattacking on his own. More of Donskov’s troops were then able to cross the Izhora River and establish a bridgehead in the village of Iam Izhora.

Donskov’s success forced General Georg Lindemann, commander of the 18th Army, to send more troops to the region. While those divisions were en route, Donskov continued to fend off attacks by Wünneberg’s men.

The fighting as it attacked the bridgehead was described in the history of the 4th SS Division: “Heavy fighting developed along the road [to Iam Izhora] itself. From the elevated west bank of the Izhora, the enemy had good observation of the entire left-handed sector of the division, which was almost devoid of cover. [Enemy] tanks fired on the main line of resistance. Extremely heavy [enemy] artillery and mortar fire covered the road.

“An immediate counterattack made it to the cemetery in the small patch of woods north of Iam Izhora, but it was brought to a halt in heavy enemy defensive fire. The road, however, or more precisely, its roughly 70 centimeter-deep roadside ditches, were the only link to forward elements.”

The Soviets continued to enlarge their bridgehead, pushing north along the east bank of the Izhora. Wünneburg’s men continued to suffer casualties as they tried to stem the Soviet advance. All the officers of the 4th SS Reconnaissance Unit were killed or wounded, and artillerymen were used to fill the gaps in the infantry units. The 4th SS even acquired a cynical nickname—the Birkenkreuz (birch cross) Division, symbolizing the crosses used to mark the graves of its dead.

Red Army forces also applied greater pressure to the Demiansk salient and to German units in the Staraya Russa area. The attacks achieved little as far as territory gained, but they did keep the Germans off balance, forcing them to reinforce those areas with units of the 16th Army that could have been used for the impending assault on Leningrad.

While those actions were taking place, Stavka was planning another surprise. Unaware of the impending arrival of the 11th Army, the Soviets decided to start an even larger operation to disrupt possible enemy attempts to take the offensive and at the same time clear German forces from the Mga salient south of Lake Ladoga with the intention of restoring a land line to Leningrad.

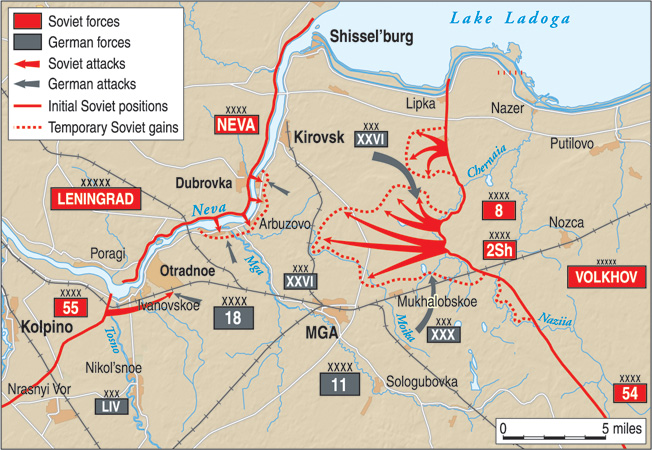

The plan called for Govorov’s Leningrad Front to launch an attack across the Neva River about 12 kilometers south of Shissel’burg with his Neva Operational Group. Another attack would be launched by Svirdov’s 55th Army about 12 kilometers farther south near Ivanovskoe.

Lieutenant General Kiril Anfansevich Meretskov’s Volkhov Front would attack from his bridgeheads on the Volkhov River using Lt. Gen. Filipp Nikanorovich Starikov’s 8th Army as its spearhead. If all went according to plan, the two fronts would join forces at Siniavino, cutting off German units between there and Lake Ladoga. The attacks would be supported by the Red Air Force, the Baltic Fleet, and the Ladoga Flotilla.

It sounded like a good plan, but the area to be attacked would be an extremely hostile environment. Besides extensive German defensive positions, the Soviets would also have to contend with terrain that was heavily forested, contained few roads, and included many marshes and wetlands. The forests and wetlands not only hindered the movement of artillery and vehicles, but also prohibited good observation for both attacker and defender.

One of the few good observation sites lay on the Siniavino Heights, about 150 meters higher than the surrounding terrain. The heights not only gave a commanding view of the area, but were one of the few points unaffected by marshy conditions. The Germans had built a strong defensive line that was anchored on those very heights.

As the Soviets assembled forces for the attack, the Germans were also grouping their units for Nordlicht. Brig. Gen. Erwin Sander’s 170th Infantry Division, one of the first divisions arriving from the Crimea, was ordered to move into the Mga salient. Also en route to the salient were four Panzerkampfwagen VI Tiger I tanks, fresh from the assembly line. The tanks, part of Heavy Panzer Unit 502, did not have track mudguards and were still supported by factory teams. They would prove virtually useless in the coming battle due to the inhospitable terrain.

The Soviets had been careful about assembling their forces. Mindful of German air superiority in the vicinity, many of the Soviet units traveled to their jump-off areas under cover of darkness. German patrols and air reconnaissance noticed little change in the enemy’s dispositions. On August 6, Halder wrote, “Local fighting flares up at Kirishi and Leningrad.” Ten days later he noted, “Attacks against 16th Army, as in past days, in 18th Army sector, rather quiet.”

The quiet in the 18th Army’s sector was about to come to an end. Although the 4th SS was still facing a stalemate, the division was about to bear the brunt of a new attack. Soviet units crossed the Neva at Ust’-Tosno and Ivanovskoe, at the juncture of the Neva and Tosno Rivers. They managed to establish bridgeheads in both areas but soon encountered increasingly stiff resistance. Strongpoints in the area held up the Soviet advance, which was also hindered by lack of leadership within the bridgeheads and poor artillery support.

One such strongpoint was manned by Sergeant Rudolf Seitz. Armed only with small weapons and a 37mm antitank gun, Seitz and a handful of men held off Soviet attempts to take a key road junction. After holding the Soviets at bay for several hours, the position was threatened with encirclement. Seitz ordered his remaining men to retreat, but he stayed in the position and continued firing, assisted by a Corporal Eggersdorffer. Finally, about to be overrun, the two men destroyed their gun and made it back to their own lines.

Although the Soviets received reinforcements, the SS were also strengthened by elements of the 61st Infantry and 12th Panzer Divisions, as well as by a security battalion. Thwarted in his initial attempt to breach the German defenses, Govorov called off the planned river crossing by the Neva Operational Group until the beginning of Meretskov’s offensive. Even though the crossing was postponed, the Soviet forces still holding on in the bridgeheads continued to harass the Germans.

Reinforcements from elements of three rifle divisions (43rd, 70th, and 136th) helped the bridgehead forces replace losses. It also allowed them to attempt further eastward movement. A cat and mouse game developed as opposing forces sought each other out. In the early hours of August 20, 1st Lt. Mailhammer of the 4th SS Artillery Regiment reported, “The Russians are in the woods in front of us…. We have engaged the enemy over open sights.”

Meanwhile, Manstein, on his way to the Leningrad sector, stopped off at Hitler’s headquarters. Meeting with Halder, he discussed his role in the Leningrad attack. He later wrote, “Halder made it quite clear that he completely disagreed with Hitler’s proposal to take Leningrad in addition to conducting an offensive in the south [Stalingrad], but said that Hitler had insisted on this and refused to relinquish the idea.”

While those talks were taking place, the action along the Tosno River continued with more forces being funneled in by both sides. Several Soviet tanks also joined the fight, crossing the river from their laager around Kolpino. Supported by gunboats on the Neva and air and artillery, the Soviets strove to encircle Ivanovskoe from the south. They were met with counterattacks from the SS Police and 12th Panzer Divisions, as well as elements from the arriving 5th Gebirgs (Mountain) Division. In touch and go fighting on the 20th, the Germans were able to maintain their lines against several fierce attacks.

On August 21 (some sources indicate August 23), Hitler formally gave the Nordlicht operation to Manstein. The field marshal would be allotted three army corps to break Soviet positions south of Leningrad. They would be supported by the three siege batteries that had been brought up from the Crimea as well as divisional, corps, and army artillery batteries. The attack was to be two-pronged after the initial penetration was made, with one corps setting up south of the city and two corps attacking east, forcing crossings of the Neva River. Once Soviet forces between the Neva and Lake Ladoga were eliminated, the two corps would swing toward Leningrad, cutting it off from the east. With the city cordoned off, Hitler was certain he could force its surrender by subjecting it to constant artillery and air attacks.

Hitler even went so far as to subordinate the attacking forces directly to OKH. The subordination jumped the chain of command, as Manstein’s forces would normally be under the control of Küchler’s Army Group North. Apparently, this was one of the Führer’s mini-management ploys to ensure that his orders would be carried out to the letter.

Manstein was skeptical about the Leningrad assault, having recently witnessed the fierce house-to-house fighting at Sevastopol. “We realized from our reconnaissance that 11th Army must on no account become involved inside the built-up areas of Leningrad, where its strength would be rapidly expended,” he wrote in his memoirs. “As for Hitler’s belief that the city would be compelled to surrender through terror raids by 8th Air Corps, we had no more faith in this than had Col. Gen. von Richtofen, the force’s own experienced commander.”

The field marshal still had to keep an eye on the 18th Army’s battle at the junction of the Tosno and Neva Rivers as he prepared for his own offensive. The heavy siege batteries from the Crimea were already in place in camouflaged positions that had apparently escaped the eyes of Soviet reconnaissance aircraft. Although some elements of his Crimean divisions had been diverted to the Neva front, a steady stream of units were making their way to assembly points for the main attack.

On August 22, the Soviets renewed their attacks out of the Tosno-Neva bridgeheads. In the early morning fog, Soviet infantry was able to penetrate the lines of Colonel Otto Gieseke’s Police Rifle Regiment 1 in the regiment’s 1st and 2nd Battalions’ sectors. The Soviets were then able to advance south along a road bordering the eastern bank of the river. There, they ran into blocking positions occupied by elements of Captain Wilhelm Dietrich’s III/Police Rifle Regiment 1. Supported by a heavy infantry gun platoon, the Germans were able to stop the Soviets at a brickyard, where they held them at bay until support came from the 100th Mountain Regiment’s 3rd Company. Counterattacking, the Germans regained their main line by the end of the day.

For the next four days, German and Soviet soldiers continued to slug it out. Attack was met by counterattack, and artillery from both sides caused heavy casualties. Two companies of the 121st Infantry Division and an entire battalion of the 61st Infantry Division had to be pulled out of the line simply because their fighting strength had fallen to only a few men.

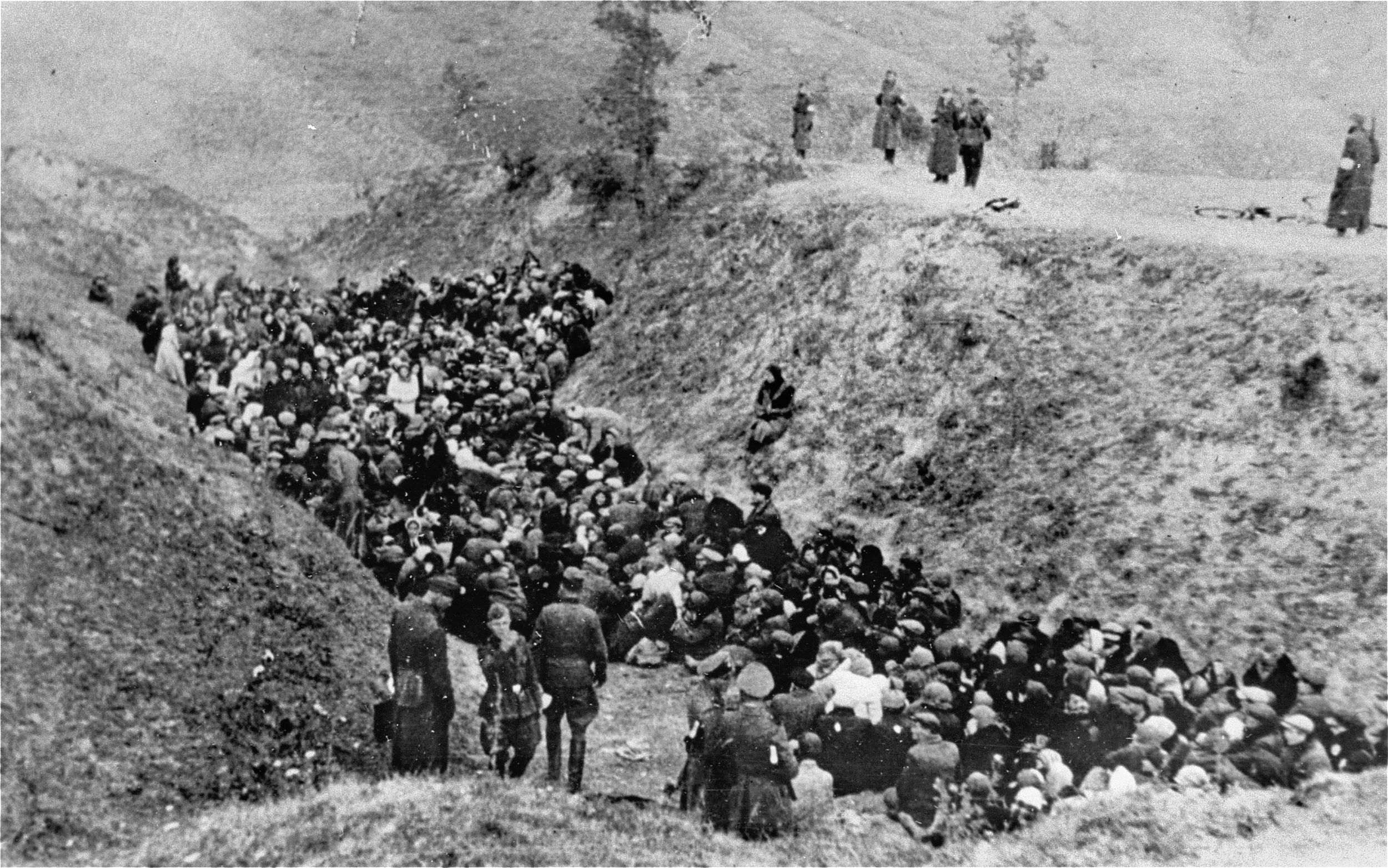

Meanwhile, Manstein continued to fine tune his plans for Nordlicht. Although he was determined that his forces would not be bogged down within the city, it is interesting to note that neither he, Lindemann, Halder, nor any other higher commanders seemed to have any qualms about the complete destruction of the former Russian capital and the eradication of its population. Hitler had said as much in an August 23 conversation with Küchler when he declared, “The attack against Leningrad must be executed with the intention of destroying the city.”

The Soviets, however, had different plans. Meretskov was finally ready to strike. Although the Germans knew a buildup was taking place and that an attack was almost certainly imminent, the Soviet general was still able to achieve an element of surprise when the leading echelons of Starikov’s 8th Army launched their assault at 2:10 amon August 27.

Major General Sergei Timofeevich Biiakov’s 6th Guards Rifle Corps struck the junction of Maj. Gen. Rudolf Lütters’s 223rd Infantry Division and Maj. Gen. Friedrich von Scotti’s 227th Infantry Division, making good headway and establishing strong bridgeheads on the western bank of the Chernaia River. With Colonel Petr Kirillovich Koshevoi’s 24th Guards Rifle Division in the lead, the Soviets continued to move forward.

The Germans were caught flatfooted by the initial assault, and it was not until noon that Lindemann reported the attack to higher headquarters. Even then, OKH did not appear to be overly concerned. In an August 27 entry in his diary, Halder noted, “The anticipated attack south of Lake Ladoga has started. The attacks on the whole were repelled; only minor local penetrations.”

Those “minor penetrations” were achieved by Koshevoi’s division, which was supported by Colonel David Markovich Barinov’s 19th Guards Rifle Division and Colonel B.N. Ushinskii’s 265th Rifle Division. More Soviet troops crossed the river, and with solid bridgeheads behind them the three divisions pushed forward about three kilometers, capturing the village of Tortolovo and surrounding German units in Porech’e.

On the right flank of the assault, an attempt to widen the breach to the north by Maj. Gen. Nikolai Moiseevich Martynchuk’s 3rd Guards Rifle Division ran into problems attempting to overrun Colonel Maximilian Wengler’s 336th Grenadier Regiment of the 227th Division near the village of Gontovaia Lipta. Although the Soviets succeeded in surrounding the regiment, Wengler’s Westphalians held positions on the edge of a small forest, keeping the Soviets at bay and forcing them to use all the 3rd Guards’ reserves in an effort to break them instead of continuing to drive north. This action gave other units of Scotti’s division time to stabilize their positions.

On the opposite side of the bottleneck, the Neva Operational Group’s 86th Rifle Division, under Colonel Pavel Sergeevich Fedorov, had already launched an assault across the Neva. Using swift assault boats, Fedorov’s men quickly crossed the river, which was only about 240 meters wide at that point, and established a bridgehead directly across from Dubrovka.

Fedorov ordered his men to expand the bridgehead, but as they moved inland they were met by formidable German defenses within a kilometer of the riverbank. Although brought to a halt in front of the German line, the Soviets had gained another toehold on the Neva’s eastern bank that would require more German forces to contain.

On August 28, Barinov and his neighboring divisions continued a slow advance through the marshes and forests east of Siniavino. By nightfall his lead elements were within six kilometers of the southeastern approaches to the commanding position, but they were meeting increased resistance as they continued to advance.

Elements of Brig. Gen. Julius Ringel’s 5th Mountain Division and Maj. Gen. Johann Sinnhuber’s 28th Jäger Division were ordered to advance toward Mga from the Nordlicht staging areas, and part of Brig. Gen. Walter Wessel’s 12th Panzer Division was sent to reinforce German positions on the Neva. Although the situation was one of confusion, the German high command was finally realizing that a dangerous situation was developing. Halder noted, “In the north, a very distressing [enemy] penetration south of Lake Ladoga.”

In the 4th SS Division sector, most of the Soviet troops that had occupied the bridgehead near Ivanovskoe’ had been wiped out, and the SS troops were using the time to reorganize their depleted battalions. Although seeking a few days of rest, the division was once again put on heightened alert when word of Soviet attacks in the eastern part of the bottleneck were received at 6:15 pmon the 28th. A relatively quiet day passed on the 29th, but the division was hit by concentrated artillery fire at 4 amon the 30th, followed by an attempt to cross the Tosno, which was repulsed.

Meanwhile, heavy fighting was raging south of the Siniavino Heights. The four Tiger tanks at Küchler’s disposal were sent to join the action on the 29th after detraining at Mga, but three of them broke down almost immediately due to transmission failures. The fourth found itself practically immobilized by the horrendous road system and lack of bridges heavy enough to support its weight as it tried to struggle forward.

Although the Soviets were tantalizingly close to their first objective, the arrival of more German forces stalled their advance toward Siniavino. Biiakov’s 6th Guards Rifle Corps was being bled white as it strove to breach the German defensive positions around the heights, which were considerably stronger than Meretskov’s intelligence had suggested. However, the Soviets were still able to hold onto their previous gains.

On August 30 Halder wrote, “In the north, the enemy continued his attack south of Lake Ladoga without making significant gains, but neither did our attack achieve any important objectives. The forces set aside for the Leningrad offensive are increasingly diverted to this sector to repel the enemy drive.” In that sense, the Soviets were achieving one of the main objectives of their offensive.

With both sides basically stymied, the opposing commanders had to make some decisions that would further affect Nordlicht. Lindemann and Meretskov used the 31st to devise new plans for the battle, which had changed the situation on the Leningrad Front. What had been a basically static line for the past few months was now a battleground on which armies from each side were mounting or preparing to mount an offensive in the same area. By striking first the Soviets had upset the German timetable, but the available German forces near the main thrust of the Soviet assault also forced Meretskov to speed up his careful plans for following up his initial attack.

Major General Nikolai Aleksandrovich Gagin‘s 4th Guards Rifle Corps (259th Rifle Division, 22nd, 23rd, 32nd, 33rd, 53rd, 137th and 140th Rifle Brigades and 88th and 122nd Tank Brigades) had been scheduled to follow Biiakov’s corps in bulk after the initial assault had cleared the Siniavino defenses. That plan was already scrapped, as Meretskov had been forced to send Maj. Gen. Mikhail Filppovich Gavrilov’s 259th, along with a tank brigade, to bolster Biiakov’s corps on the 29th. Due to the heavy fighting, the other brigades were committed piecemeal, lessening the effect of a massed assault. The result was that the German defenders fought a steady tide of infiltrating Soviet units instead of a massed attack from Gavrilov’s corps.

All this added to the confusion among attackers and defenders in the heavily wooded area. Even so, with the help of the men of Gavrilov’s corps, Biiakov was able to shift his own units for a more concentrated attack. Sergeev’s 128th Rifle Division hit the fortified position at Worker’s Settlement No. 8, held by the II/374th Regiment of Maj. Gen. Karl von Tiedemann’s 207 Sicherungs (Security) Division.

The heavily outnumbered Germans, lightly armed and surrounded, defended the settlement vigorously. House-to-house fighting ensued, and after hours of combat the position was taken. The battalion’s sacrifice was not in vain, as the time taken to capture the strongpoint allowed German reinforcements to be shifted to the area, stopping Sergeev’s advance after it had gained up to three kilometers.

Farther south, Colonel I.V. Gribov’s 11th Rifle Division fought elements of Maj. Gen. Hans von Tettau’s 24th Infantry Division for control of the strongpoint at Mishino. After another bitter struggle, the Germans were forced to retreat. The attack was in conjunction with Colonel Dmitri Lvovich Abakumov’s 286th Rifle Division, which was tasked with capturing Voronovo, about five kilometers to the south. With this accomplished, the Soviets would have secured their southern flank, forming a defensive line to meet German attacks in that area.

Voronovo, however, was a tougher nut to crack. Defended by elements of Lütter’s 223rd Infantry Division backed up by a battle group from the 12th Panzer Division, the Germans were at Voronovo in strength. The initial Soviet assault withered away in the face of fierce, effective defensive fire. Abakumov ordered a second assault, which met the same fate. The bodies of Red Army soldiers continued to pile up against the German defenses as fresh troops charged again and again until Abakumov finally called off the attack.

Meretskov had meticulously planned support for the initial attacks of the Volkhov Front, providing massive artillery and air power to pummel the Germans. The heavy woods and marshland, along with poor communication between commands, largely negated the effects of the artillery except when there was a clearcut understanding between forward artillery observers and their units.

In the air, Ivan Petrovich Zhuravlev’s 14th Air Army outnumbered its German opponents by about 2-1. However, the German pilots facing Zhuravlev managed to maintain air superiority, even with inferior numbers. Major “Hannes” Trautloft’s Jägdgeschwader (JG) 54 and Major Gordon Gollob’s JG 77 took to the skies, inflicting serious damage to the Red Air Force. On September 1-2 alone, the German fighters knocked 42 Soviet aircraft out of the sky, which had a disparaging effect on Red Air Force pilots. German fighters noticed that Soviet pilots turned as soon as they spotted enemy aircraft. The situation grew so bad that Stalin himself threatened to court martial any pilot refusing to engage the enemy.

While the Luftwaffe and Red Air Force dueled in the sky, the ground war continued unabated, with both sides throwing in more troops. By September 3, the Soviets were almost 10 kilometers inside the German lines in the Siniavino area with only five kilometers to go before they could capture the important junction of the Kirov railroad at Mga.

To the west, the 4th SS once again became the recipient of heavy Soviet attacks, this time supported by truck-borne Stalin’s Organ rockets batteries. The rockets were also known as Katyushas (Little Kates). The Soviets were hoping to cut the railway to Mga south of Usti Tossno. The 1st and 3rd Police Rifle Regiments took the brunt of the attacks, and although some penetrations were made, the Germans were able to seal them off and destroy the enemy troops.

In recounting the September 3 fighting, the 4th SS divisional history states: “The stubbornness of the Russians was admirable. At 1700 hours the attack came, initially in the sector of Polezei-Schützen Regiment 3. It was followed half an hour later by additional attacks on Polezei-Schützen Regiment 1. All of the attacks were halted in the final protective fires of the Polezei Artillery Regiment. The lack of imagination of the Russian command in infantry combat at that time was conspicuous.”

Lack of imagination or not, the Soviet offensive had its effect in Berlin. Hitler had become increasingly nervous about the action around Leningrad, and he looked to Manstein to rectify the situation in the bottleneck. In his memoirs, Manstein wrote, “On the afternoon of 4 September, I received a telephone call from Hitler in person. He told me it was essential that I intervene on the Volkhov Front to prevent a disaster there; I was to assume command myself and restore the situation by offensive action.”

Manstein, in effect, was relieving the 18th Army of command in its own sector. Although the order had come directly from Hitler, Lindemann’s staff was offended by the move. They did, however, do their best to support Manstein for the upcoming battle. As he formulated his next move, Manstein, along with other senior commanders, knew the preemptive Soviet attack had made implementing Nordlicht impossible. The German forces preparing for the attack on the city would instead be used to wipe out the Soviet gains of the last few days and return to the status quo.

The observation posts on the Siniavino Heights helped Manstein deploy his troops by identifying Soviet positions and troop movements. Artillery observers plotted targets for the coming attack and kept the Luftwaffe updated on targets of opportunity.

As Manstein planned his next move, Meretskov became increasingly frustrated with the advance of his own troops. In an effort to regain the initiative, he ordered the remains of Lt. Gen. Nikolai Kuzmich Klykov’s 2nd Shock Army into the battle. These troops ran headlong into Wandel’s 121st and Lütters’ 223rd Infantry Divisions, which were supported by Sinnhuber’s 28th Jäger Division and Ringel’s 5th Mountain Division.

While the Soviets were occupied with those forces, Manstein ordered a strike at their right flank. On September 6 the Germans advanced, driving the enemy from Kruglaia Grove, about six kilometers east of the heights. Meretskov was then forced to relocate some of the troops from his vanguard to try to contain the German forces.

Not everything went the Germans’ way. In the west, heavy attacks on the 4th SS made some gains along the Kirov railway. The fighting took a heavy toll on both sides, and on September 7, the 4th SS reported an effective fighting strength of only 1,938 men.

Farther east, Manstein ordered the 24th and 170th Infantry Divisions and the 12th Panzer Division to hit the Soviets’ southeastern flank. As was true with the initial Soviet attack, the terrain favored the defenders. Soviet engineers had been working at a feverish pace since the beginning of the offensive. Although Meretskov had been thwarted in trying to extend his left flank, the Red Army engineers had sown minefields in the area to guard the flank.

For once, Soviet artillery observers had good communications with the extensive artillery units in the rear and were able to bring down heavy fire on the German infantry from their superbly concealed positions. Deprived of infantry support, the German tanks kept going but soon ran into the recently laid minefields, causing considerable losses among the armored vehicles.

The armor retreated, but the infantrymen gave it another go on the following day, September 11. They were met with Soviet counterattacks that forced Manstein to cancel further major operations in the area for the time being. Ordering reconnaissance units to locate enemy strongpoints, he then sent teams of engineers to destroy them one at a time.

Impressed by the Soviet artillery, Manstein also telephoned Berlin to speak with Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, the Chief of Staff of OKW. He informed Keitel that the Soviet artillery would have to be located and destroyed by the Luftwaffe and his own artillery before another setpiece attack from both the north and south could be launched.

While the Luftwaffe and army artillery pounded recognized Red Army positions, German forces nibbled away at the Soviet defenses. Although it was not an all-out offensive, the Soviet salient was slowly being reduced in the area that now extended from Siniavino to Gaitlovo. With the Soviet artillery being suppressed and their ground forces grudgingly retiring, the field marshal decided it was time to strike the final blow.

Manstein set September 18 as the date for a full-fledged attack on the Soviet salient, but weather intervened with rain and fog. For three days the Luftwaffe was hampered by poor visibility. Although it could still strike at known enemy artillery positions, the weather made it impossible for the airmen to provide the close support that German ground forces were counting on.

While Manstein waited, Meretskov was fuming. Earlier in the month, he had taken the 4th and 6th Guards Rifle Corps from Starikov’s 8th Army and placed them under Klykov, hoping that a unified command would make thing easier to control. The change did little good, and Meretskov was feeling heat from Moscow. Stavka was demanding results, and it wanted them quickly.

The weather finally broke as Meretskov was making new plans to satisfy the high command. Manstein launched his assault with attacks on both the northern and southern Soviet flanks with the objective of his two spearheads meeting at the village of Gaitolovo, which contained the only decent road to supply the salient. When this was accomplished, Klykov would be cut off from the Volkhov Front, and the pocket around Siniavino could then be eliminated.

Just as the German attack began on September 21, Meretskov submitted a revised plan of operations for Stavka’s approval. It varied little from his original plan and called for the capture of the Siniavino Heights before advancing further west to link up with units of the Leningrad Front. He also called for the 376th Rifle Division to be released from the Front reserve to help settle the situation at the Kruglaia Grove and for the 372nd Rifle Division to be release to help capture the heights. In addition, Meretskov asked for 100 heavy and medium tanks for his ground offensive and three fighter regiments to reinforce his aviation assets and for the transfer of the 314th and 256th Rifle Brigades, as well as the 73rd Tank Brigade, to reinforce his units after the capture of Siniavino. While Stavka weighed Meretskov’s requests, the Germans rolled forward.

In the north, Wandel’s 121st Infantry Division struck elements of the 4th Guards Rifle Corps. Supported by air and artillery fire, the German infantry managed to make some progress against a desperate Soviet defense, but the going was slow. On the southern flank the 24th, 132nd, and 170th Infantry Divisions formed the battering ram. Sinnhuber’s 28th Jäger held the western part of the salient, preventing any Soviet advance toward the heights.

The Germans suffered substantial casualties as they ran up against the Soviet positions. Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers and other aircraft were called in to pound the Soviet defenses. As soon as the Luftwaffe departed, the Germans rushed forward but were still met by a withering fire from the surviving Red Army soldiers. On the first day of the attack, the 131st reported casualties of 16 officers and 494 men.

The following day, four Tigers and several Panzerkampfwagen IIIs were brought up to support Sander’s 170th Infantry Division. Once again, the ground was totally unsuitable for their deployment. One of the Panzer IIIs was knocked out after crossing a causeway, and a Tiger was hit by antitank fire, followed by an engine breakdown that immobilized it. The other tanks became bogged down in the marshy terrain. Three of the Tigers were recovered, but the fourth remained stuck dead in the marsh until the Germans finally blew it up later on November 25.

The 132nd had better luck on the 22nd. By sunset, one of its regiments had fought its way to within about a kilometer of Gaitolovo before being stopped by units of the 6th Guards Rifle Corps. The noose was tightening, but the pocket was not yet sealed.

Early on the 24th, with his only supply road being threatened, Meretskov received approval to initiate his submitted plan. However, Moscow refused his request for additional aircraft. Meanwhile, heavy fighting took place on both flanks of the 2nd Shock Army, further reducing the tenuous Soviet hold in the north and the south.

In an attempt to help Meretskov’s planned advance to the Neva, Govorov announced that his Neva Operational Group could commence another cross-river attack as soon as he was given permission. Around midnight on the 24th, he received that permission to go ahead with his assault at dawn on the 25th. It was hoped that this attack on the German eastern flank would draw off troops from the Siniavino sector, allowing the 2nd Shock Army to take the heights and then link up with the Neva forces. Whether there was a breakdown in communication or some other glitch, Govorov would take another full day before he began his attack. By then it was too late.

During the morning of the 25th, Captain Friedrich Schmidt, commander of the 3/I/437th Infantry Regiment of the 132nd, pushed his company forward once again. The Russian defenders around Gaitolovo resisted stubbornly, but the 28-year-old Schmidt kept his men moving, destroying antitank and machine-gun positions and calling in artillery for extra support. By noon his exhausted men had fought their way into the center of the burning village, cutting Klykov’s supply line and digging in to resist the Soviet counterattacks that were sure to come.

Later in the day, advance elements of the 121st entered the village from the north. With the added manpower, Soviet attacks to regain Gaitolovo were smashed. More German units arrived to consolidate the position, and by the end of the day the pocket had been sealed. Thanks to the young captain from Munich, most of the 2nd Shock Army was surrounded for the second time in less than half a year.

Govorov finally began his belated attack across the Neva on the 26th. Elements of the Neva Operational Group streamed across the river in assault boats during the predawn darkness, hitting part of the 12th Panzer Division, which had established strongpoints along the river. The assault units of Colonel A.A. Krasnov’s 70th Rifle Division, Colonel Pavel Sergeevich Fedorov’s 86th Rifle Division, and the 11th Separate Rifle Brigade established bridgeheads at Arbuzovo, Moskovkaia, Annenskoe, and Dubrovka. Guns, mortars, and a dozen tanks were ferried across to reinforce the bridgeheads, but the Soviets failed to expand them in the face of heavy German resistance.

Wessel’s panzers launched a counterattack joined by elements of the 28th Jäger, and within another eight days the Soviets were ordered to abandon their bridgeheads and make their way back to the western bank. Their casualties had been heavy, and the action had done nothing more than delay the extinction of the Soviet forces inside the pocket for a few more days.

With supplies running low, the Soviets trapped inside the pocket could only sit and wait for the Germans to come. Although bravely manning their positions, the outcome was in little doubt. Advance elements of Maj. Gen. Hans Kreysing’s 3rd Mountain Division, which had been shipped from Finland, helped isolate the 6th Guards Rifle Corps.

Hard fighting between September 30 and October 15 saw division after division trapped inside the pocket disappear. Although some Soviet troops were able to slip through the German lines, the butcher’s bill for the Volkhov and Leningrad Fronts was horrendous. Divisions involved in the operation suffered 113,674 casualties out of a total of 190,000 men that were committed.

For the Germans, the cost was 26,000 casualties. However, the Soviets had succeeded in preventing the Nordlicht operation. Those German divisions earmarked for the operation were worn out, and events on other areas of the Eastern Front would prevent the order for the operation ever being issued.

The Soviet assault on Siniavino was plagued by several issues. Some of the divisions committed had a totally inadequate supply of ammunition, and tank support was either nonexistent or doled out in dollops rather than consolidated in a strong centralized force. Command, control, and communications between headquarters and subordinate units were abysmal in many cases, and adequate reserve forces were not readily available to exploit any potential breakthroughs.

Although the siege of Leningrad would go on until January 1944, the city had received a respite. As the German divisions rested and refitted after more than a month of heavy combat, Manstein flew to Hitler’s command post to officially receive his field marshal’s baton. He was then informed that he would take his 11th Army headquarters to Army Group Venter near Vitebsk, where intelligence sources indicated the Soviets were planning a large offensive. His departure put the final nail in Nordlicht’s coffin.

Pat McTaggart, a longtime contributor to WWII History, is an expert on the war on the Eastern Front. He resides in Elkader, Iowa.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments