By William E. Welch

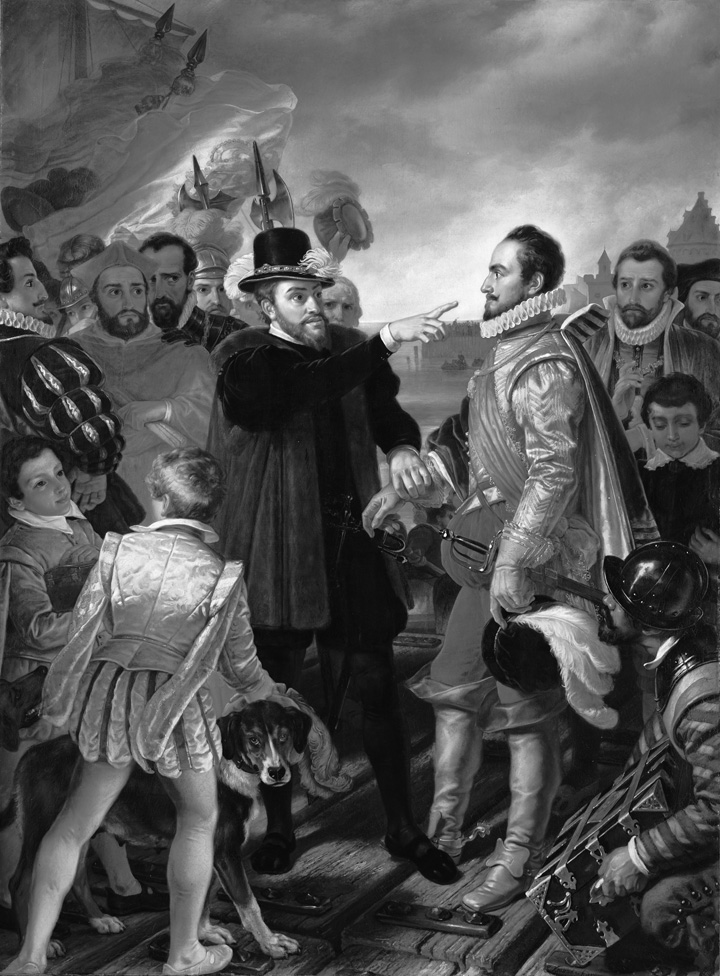

On Sunday, March 18, 1582, 37-year-old Dutch Stadholder Prince William of Orange attended a festive luncheon in his palace in Antwerp to celebrate the birthday of major ally French Duke Francis of Anjou, who had arrived in the Low Countries the previous month to support the Dutch in their rebellion against the Spanish crown.

When the meal was over, William agreed to meet with a petitioner in an alcove adjacent to the dining area. The previous year King Philip II of Spain had placed a substantial bounty on the Prince of Orange’s head, and for the most part he had remained secluded in the palace, but it was hard for the modest prince to turn his back on those seeking his assistance with their affairs.

The 18-year-old man, whose name was Jean Jauregay, was a junior clerk employed by a Spanish merchant based in Antwerp named Gaspar de Anastro who had fallen on hard times and lost five of his ships. Spanish agent Jean de Yzuncam, who was working undercover in the Netherlands, pressed Anastro to assassinate William to claim the reward. Anastro did not want to risk his life, so he recruited the impressionable Jauregay for the dangerous mission.

William sat down to receive the petitioner. Standing nearby were his 14-year-old son Maurice and several courtiers serving as bodyguards. When Jauregay approached the prince, he pulled a pistol out of his pocket and shot the prince at point-blank range. The inexperienced youth had overcharged his gun, and he was knocked backward by the recoil. The bullet, which had an upward trajectory, went through the prince’s neck, through his mouth, and exited from his cheek. William thought the building had collapsed so violent was the explosion. The prince’s bodyguards and his son lunged toward the assailant and stabbed him repeatedly. Although the single bullet did not inflict a mortal wound, William’s physicians had great difficulty keeping the wound closed in the days that followed.

His health fluctuated wildly over the course of the next six weeks as he succumbed to fevers, but he finally made a full recovery. As he re-entered public life, William and those close to him wondered whether he would be so lucky the next time there was an attempt on his life.

William was the eldest son of Count William of Nassau Dillenburg, a devout Lutheran, and his second wife, Juliana von Stolberg. He was born in 1533 in the village of Dillenburg in the County of Nassau along the Lahn River, a right tributary of the Rhine River. It was a pastoral area with orchards of plum and cherry trees, thick tracts of woods blanketing low ridges, and meandering streams.

Young William would not live the low-profile aristocratic life of his father, whose main occupation was looking after his meager estates and large family. William would find himself playing a pivotal role as a result of events that substantially increased his inheritance and catapulted him to the upper echelon of European nobility.

Fate had it that William’s cousin, René of Chalons, who was the ruler of the Hapsburg principality of Orange in Provence and Stadholder of Holland and three other provinces in the Spanish Netherlands, was cut down at the young age of 25 in battle during the siege of St. Dizier in 1544. In his will, René left his substantial inheritance to his 10-year-old cousin William. In the late 12th century, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I had made the Burgundian County of Orange a sovereign principality within the empire. This development put William, the new Prince of Orange, in the center of a political storm that was brewing in the Netherlands.

Since René had been a prince of considerable note among the Netherlanders, his benefactor, the staunchly Catholic Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, deliberately made sure that the inheritance passed not to René’s uncle, William of Nassau-Dillenburg, who was a Lutheran, but instead to his impressionable young son.

In almost the wink of an eye, William inherited vast estates in northwestern Europe, including the sovereign principality of Orange, and substantial estates in Brabant, Luxembourg, Flanders, Franche-Comte, Dauphine, and Charolais. Charles V instructed that William should be sent to Breda in northern Brabant, the seat of the Nassau family. It was only a two-day ride from Breda to Antwerp where William would take his place as the Prince of Orange in the Imperial Court of The Netherlands under the watchful eye of the emperor.

Shortly afterward William became part of the emperor’s court in Brussels. Charles V intended to raise him as a devout Catholic prince faithful to the emperor and to the pope. Charles tested William’s military aptitude and capabilities by designating him the nominal head of an army of 20,000 men during the Italian Wars that pitted the Hapsburg Empire against the Valois dynasty of France. William served Charles V for a decade until the emperor abdicated in 1554 and passed responsibility for the Netherlands to his son, King Philip II of Spain.

William did not show any great aptitude as a military commander; however, he did show great promise as a diplomat. He was one of three representatives at the peace table and helped negotiate the Peace of Cateau-Cambresis in 1559 between Henry II of France and Philip II of Spain. The peace ensured that after nearly seven decades of war between France and the Hapsburg Empire over control of Italy, the Hapsburgs won the struggle and the French ceded their territorial claims in Italy to the Hapsburg Empire and the County of Savoy.

The year after William stepped down from his post as commander of the Hapsburg forces on the Flemish border with France, a young man named Balthasar was born to the devoutly Catholic household of the Gerards, who resided in the village of Vuillafans in Franche-Comte, one of the Hapsburg dominions. Balthasar, who had 10 siblings, was quiet and studious, as well as passionate and intense. The Gerards, like many other Catholic households in Franche-Comte, had prospered under the benevolent rule of the Hapsburgs. His family was affluent enough for him to attend the nearby Catholic University of Dole where he studied law.

Gerard wound up not as a lawyer, but as a cabinetmaker’s apprentice who was a fanatical admirer of Philip II. In one documented workplace incident, he thrust his dagger visciously into a piece of wood vowing to do the same to the Prince of Orange. When Philip reached the point by 1581 that he publicly announced a reward to whoever could assassinate William, Balthazar answered the call.

William had first met Prince Philip, the future King Philip II of Spain who would rule not only Spain, but also the Netherlands and the Spanish territories in Italy, in 1549. Despite being six years older than William, the introverted Philip disliked the younger prince, who was far more self-confident and socially at ease than Philip. Nevertheless, Philip behaved in a civil and cordial manner toward William as required by his high-born status.

When Charles V abdicated and turned over the reins of power to Philip in 1555, the new Spanish king and overlord of the Netherlands lost little time stepping up the war on heretics in the Netherlands. To the Protestant mix of Anabaptists and Lutherans which his father had tried to counter ecclesiastically, politically, and militarily had been added the militant preaching of Calvinism. Although it spread more slowly with fewer mass conversions in the Netherlands than it had in France, it nevertheless was gaining ground. It appealed not only to those in the northern provinces of the Netherlands, but also to the large urban populations in the southern provinces.

In 1556 larger numbers of Jesuits moved into the Netherlands. They played a role in the inquisition, which was still used to tamp down heresy by enforcing harsh edicts. The inquisition in the Netherlands was very aggressive in that even if a heretic repented he was still put to death.

Three years later Philip issued directives to reorganize the bishoprics that would have a major effect on the political power structure of the Netherlands. He established for the first time three archbishoprics within the Netherlands—Cambrai, Utrecht, and Malines—rather than have the bishoprics the Netherlands part of the German archbishoprics of Rheims and Cologne.

This meant that Archbishop of Mechelen Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle became the head of the Netherlands Council of State, of which William was a member. Thus, the council was controlled not by a group of nobles as it had been previously, but instead by an archbishop. The Catholic Church had elevated Granvelle from cardinal to archbishop in 1561 at the request of the Hapsburgs.

Although no clear connection was ever established between Granvelle and Gerard, it is an uncanny coincidence that William’s assassin also hailed from Franche-Comte. Some observers speculated in the aftermath of the assassination that Gerard may have felt some sense of duty to Granvelle.

In 1559 Philip appointed his illegitimate sister, Margaret of Parma, as governess-general of the Netherlands. Her responsibility was to ensure that Philip’s initiatives and desires were fulfilled in regard to governing the wealthy and heavily populated Hapsburg domain. The same year he also made William the stadholder, or governor, of the northern provinces of Holland and Zeeland. As such, it was William’s duty to look after Philip’s interests in the Netherlands and guard his rights as sovereign.

William mobilized the nobility of the Netherlands against Cardinal Granvelle, who was referred to by his enemies as the “red devil.” They petitioned Philip in 1562 for his removal, charging him with excessive zeal in the persecution of Protestant heretics and mishandling of church revenues. When this did not work, William and his ally, Lamoraal, Count of Egmont, withdrew the following year from the Council of State, interrupting the normal business of government. Philip relented in 1564 and recalled Granvelle from the Netherlands. Granvelle’s ouster constituted a key political victory for the Orangists.

Philip was unrelenting in his zeal to prosecute heretics. In October 1565 he signed orders requiring all provincial authorities in the Netherlands to enforce the laws against heretics. In response, Calvinists in 1566 broke into Catholic churches and smashed statutes and stained glass windows. Isolated incidents had occurred as early as 1562, but the so-called Iconoclast Fury of 1566 was widespread throughout heavily populated southern provinces. Calvinist preachers routinely held outdoor sermons in which they urged members of their congregations to do away with the symbolic trappings of Catholicism. In many cases local officials stood idly by while groups of between 50 to 100 men sacked Catholic churches.

The Iconoclast Fury led directly to Philip’s decision to send large numbers of Spanish troops into the provinces to restore order and protect the Catholic Church properties. Realizing he could not hold back the tide of revolt, William departed the Netherlands in April 1567 for the Nassau estates in Dillenburg. From that point on, William feared that he might be assassinated.

Philip replaced Margaret of Parma in December 1567 with Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, the Duke of Alba, who was a veteran commander of the Ottoman-Hapsburg Wars. Alba actively persecuted the Calvinists, which served to drive the religion underground and resulted in the departure of large numbers of Calvinist clergy and nobility from the provinces. Although William and his brother Louis of Nassau attempted to counter the Spanish military forces that occupied the Netherlands, they lacked the resources to meet them on even terms.

Alba served for five years as governor-general of the Netherlands during which time he presided over the Council of Troubles, dubbed by its detractors the Council of Blood, which sought to punish the agitators responsible for the desecration of Catholic churches. The council oversaw the execution of as many as 1,000 people. As if this were not enough, his reign of terror included the sack of key cities throughout the southern provinces and the execution of their garrisons.

William would live long enough to see three successors to Alba: Don Luis de Requesens, Don John of Austria, and Alessandro Farnese, the Prince of Parma. Of the three, only Parma realized that it was necessary to undertake diplomatic initiatives while continuing to apply military force to achieve Philip’s goals. Yet it was under Parma’s regency that the seven provinces in the north seceded from Spain in 1581.

Philip’s intransigence in regard to Calvinism compelled the majority of the southern and northern provinces to depose Philip in favor of Catholic Duke Francis of Anjou on January 23, 1581. Philip had long since considered William a traitor and he was personally stung by what he felt was a personal betrayal. Philip considered assassination to be a legitimate instrument of warfare.

Granvelle backed Philip because he wanted revenge against the prince. Granvelle had become deeply embittered by the way the Orangists had driven him from power. He delighted in the knowledge that William might be discomfited knowing that each day of his life might be his last.

On March 28, 1581, the King of Spain issued a proclamation in which he put a price on William’s head. Because William had disturbed the religious peace in the Low Countries, “every one is authorized, to hurt him and to kill him,” stated the document. Whoever succeeded could claim the reward of 25,000 gold crowns, along with land and titles.

Anjou brought troops with him ostensibly to fight the Spanish, but when he learned that he had only limited powers, he embarked on the conquest of key cities, one of which was Antwerp. Fighting erupted throughout the city on January 17, 1583, and Anjou returned to France. The provinces that had chosen Anjou as their sovereign switched their allegiance to William of Orange.

Although Gerard was intelligent and resourceful, it is hard to believe he could have acted alone for he used various different subterfuges to put himself in close proximity to the Prince of Orange. The tricks and cons included both forged testimonials and counterfeit documents. Gerard assumed the name François Guyon and maintained that he was the son of a Protestant serving man, Guy of Bensacon, who had been roundly persecuted for his religious beliefs.

Gerard carried around letters signed by prominent Catholic officials in the Netherlands that were meant to prove that he was well liked and trusted by authorities of the Spanish government. He used this as bait to entice those close to William into believing that he had access to intelligence related to the Spanish army and government that might be of interest to the Prince of Orange and his advisers. He successfully used the documentation to dupe Pierre Loyseleur de Villiers, William’s chaplain and intelligence chief, into believing that he might be a useful spy.

Gerard landed a job in Luxembourg in 1583 as a secretary to a relative who was in Parma’s Army of Flanders. One day he saw a pile of signed blank passes left unattended on an officer’s desk and he pocketed a half dozen. He tried to make contact with Parma in Hainault to inform him that he wanted to try to assassinate the Prince of Orange, but he lost his nerve and continued on to Holland, arriving in May 1584.

Gerard gained an audience with William, who by that time had returned to Holland and was living in Delft. He told the prince that it was his greatest desire in life to serve him. He showed William the stolen passes, but the count had no use for them. William suggested he deliver them to Anjou, with whom William was still corresponding. Since he had no money to purchase a gun with which to assassinate William, Gerard departed in early June for France.

Learning on the way that Anjou had died of malaria on June 10, Gerard returned to Delft to share the news of Anjou’s death with William and to see if a fresh opportunity to kill him might present itself. William once again received Gerard. He told Gerard to return to his home in France. Upon learning that Gerard was still hanging about in the days that followed, William sent him 12 crowns to pay his travel expenses.

Gerard used the money to buy a small wheellock pistol from one of William’s bodyguards. After finishing his dinner on July 10, William received several petitioners, one of whom was Gerard. When one of the petitioners knelt to receive William’s hand on his bowed head before departing, Gerard leaned toward William and fired into his upper body.

The double charge, which entered William’s body from the side, tore through his lungs and stomach. With great strength he remained standing. With his wife and step daughters watching in shock, William’s sister tried to help her brother, who had slumped down near the bottom of a staircase. By then his face was ashen gray. “Do you die reconciled with your savior, Jesus Christ?” she asked. “Yes,” he replied softly.

Philip, who was blinded by his rage, had failed to grasp that the assassination of the Prince of Orange made him a martyr for the rebellious Dutch. As such, William posed a greater threat to Spanish rule in the Netherlands as a martyr than he would have if he had remained alive.

William had the unfortunate distinction of being the first prominent political leader to be assassinated by a handgun. While the Prince of Parma reconquered the largely Catholic southern provinces for Philip, he was unable to recover the seven provinces of the north that became the United Provinces. William’s paternal bearing played a key role in bringing about their independence from Spain.

Join The Conversation

Comments