By John Wukovits

The summer of 1942 had brought uplifting news for the United States in the Pacific Theater. After a numbing series of setbacks, including the December 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent fall of Guam and the Philippines, the nation’s Navy had husbanded its depleted forces and, with the crucial aid of naval intelligence, halted the Japanese in the May 1942 Battle of the Coral Sea and the June Battle of Midway. The Army Air Forces had registered a triumph of its own in April, when Lt. Col. James Doolittle led a daring bomber raid directly into the heart of Tokyo. It was just months before the now-infamous Goettge Patrol Incident would become an international story.

At the time, the turnaround in events in the South Pacific restored previously shattered American morale. Military personnel walked about with a bit more pride to their step than before, and most men eagerly awaited another rematch with the Japanese. Especially impatient were the Marines, who yearned for the chance to inflict vengeance on the enemy for what it had done to fellow Marine units overrun on Guam and Wake.

They seemed to have their opportunity in August 1942, when elements of the Marines received orders to head into an unfamiliar locale, the Solomon Islands in the Southwest Pacific. Here was their chance to make the Japanese pay for their earlier actions. Instead of ill-supplied island garrisons, such as the enemy had defeated at Guam and Wake, they would now contend with freshly trained, well-armed Marines eager to kill Japanese. Overconfident Marines boasted that they would land in the Solomons, clear the enemy from the region, and be back in Australia within a few weeks to once again enjoy that nation’s women, steak and eggs, and beer.

Events of the first week quickly altered their outlook. After the initial landings on Tulagi and nearby Guadalcanal on August 7, military operations soured. Even before the Americans launched their first offensive, seemingly constant enemy air attacks harassed the Marines, who lacked the proper antiaircraft guns to put up a stern defense. Japanese guns on land chimed in to add to the Americans’ woes, and Japanese destroyers churned the waters off Guadalcanal to intercept and attack any shipping they spotted.

Then suddenly, and shockingly to the Marines, on August 9 the U.S. Navy pulled its vessels out of the area, claiming that it was too dangerous to retain shipping in a location subject to such intense aerial and land bombardment. “I know I had a feeling, and I think a lot of others felt the same way, that we’d never get off that damned island alive,” stated one Marine.

The mind-numbing series of blows perplexed, then angered, the Marines. They had come to fight, not wait in their foxholes for the enemy to seize the initiative. Many itched for a battle, to close with the Japanese, to prove that Americans could more than handle the situation.

An enticing prospect for action seemed to materialize on August 12. Marine patrols reported spotting what they thought could be a white flag in the region of the Matanikau River, not far from the American beachhead on Guadalcanal. Then a captured enemy sailor, lubricated with heavy doses of alcohol supplied by his American captors, divulged that many of his comrades in the jungle suffered from starvation and were on the verge of surrendering.

This could be the chance to seek vengeance for the earlier bruising taken from the Japanese. If the enemy did not surrender, the starving men would likely be in no shape to mount much of a defense and could swiftly be eliminated. It might not be the major operation many Marines awaited, but at least an expedition toward the Matanikau River could exact some revenge for the unpleasant first few days in and around Guadalcanal.

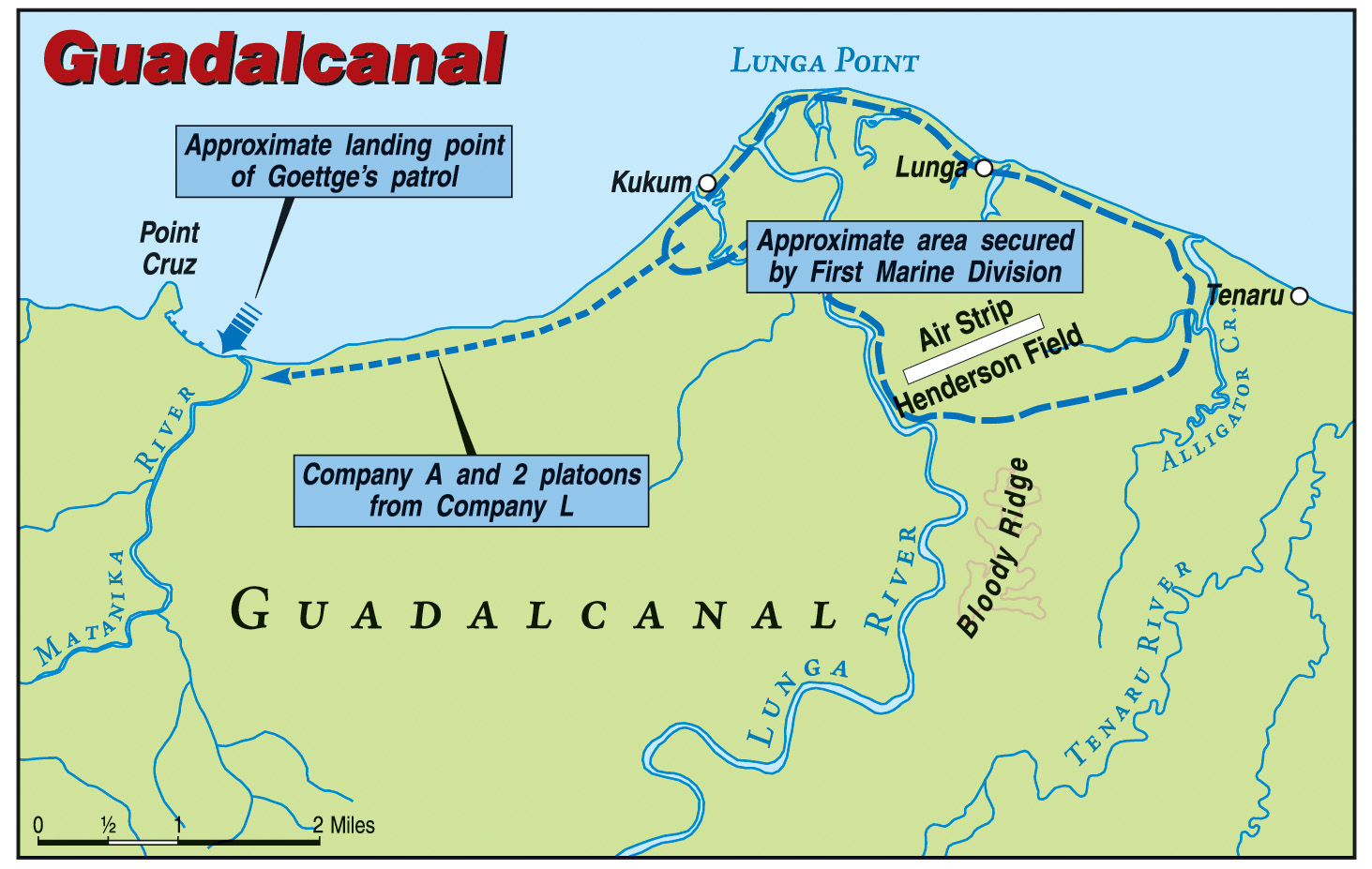

Officers hastily revamped earlier plans, which called for a patrol of 25 men to leave Kukum, close to the landing beaches, early in the morning by boat, head west, land near a spot called Point Cruz, and reconnoiter the area before darkness ended the day’s operation. After spending the night in a sheltered location in the adjoining hills, the Marines would head directly across land back toward Kukum, gaining valuable knowledge about the terrain and possible Japanese concentrations on their return.

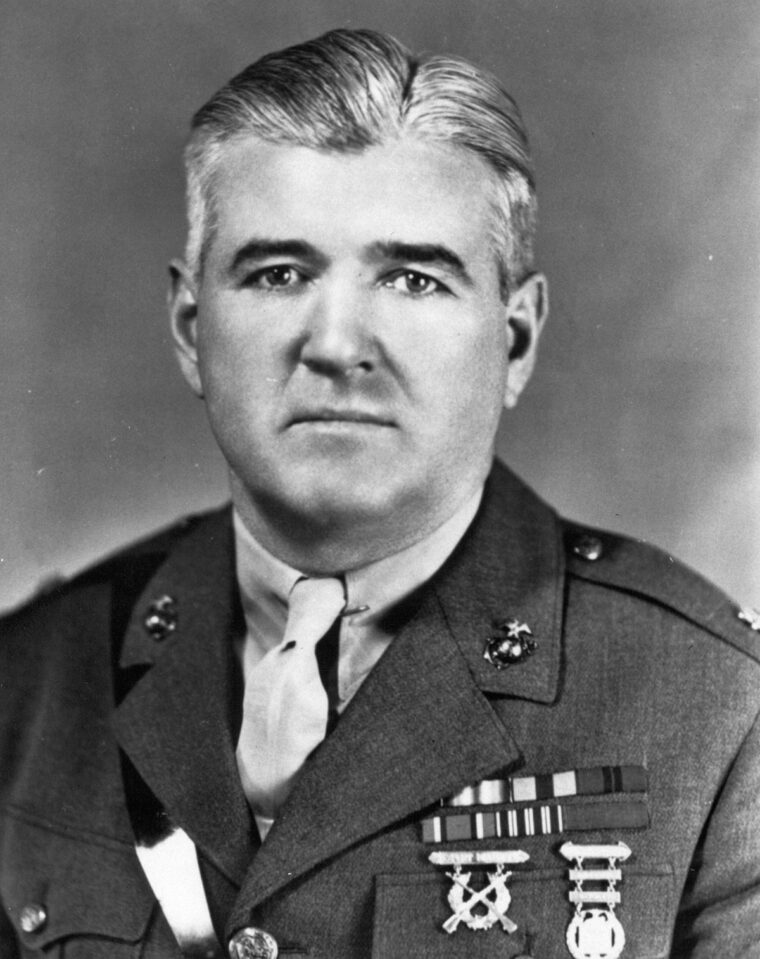

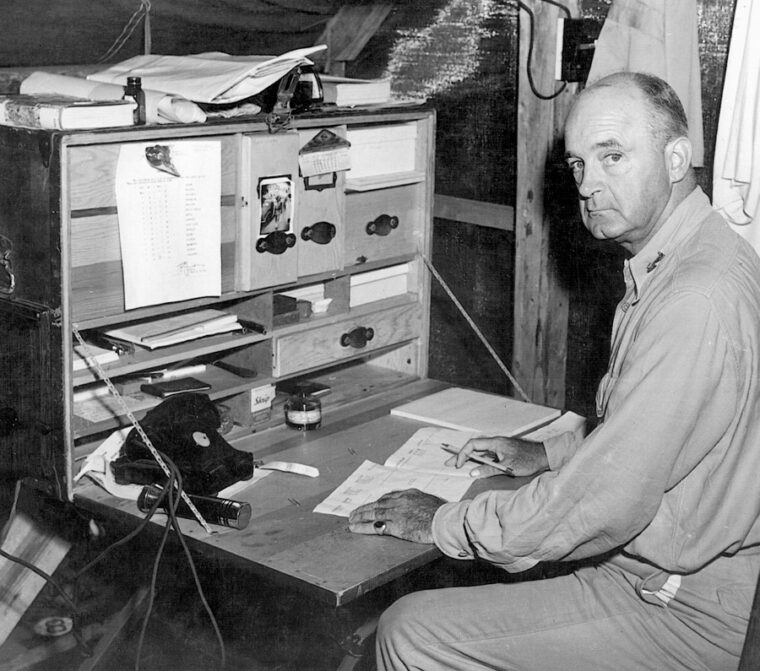

Armed with the new information provided by the Japanese sailor and by the possible white flag, Lt. Col. Frank B. Goettge, the division intelligence officer, revised the scouting plan a mere 12 hours before the patrol was to set out. He believed the information given by the Japanese captive to be true and argued that the famished and weary Japanese roaming the area of the Matanikau River would readily surrender. Goettge persuaded his division commander, Lt. Gen. Alexander Vandegrift, to let him take the mission, claiming “hundreds of Japanese troops were roaming the jungle west of us ready to surrender.”

Vandegrift should have been more cautious, especially since his Marines had little actual experience facing the Japanese, but he assented to the change. Vandegrift warned Goettge to avoid landing between the mouth of the Matanikau and Point Cruz because strong enemy forces had been spotted there only three days before. Instead, he was to land to the west of Point Cruz to be safely out of harm’s way.

The decision would later be regretted, but the Americans were still newcomers to Pacific fighting. They lacked personal knowledge of jungle warfare, and while they had heard of Japanese atrocities in China, they did not worry about the same occurring to them.

“Fierce Dark Eyes, a Wiry, Muscular Body, and He Moves with the Swift Ease of a Cat.”

Goettge gathered a group of officers to go with him, including the 5th Marines’ surgeon, Lt. Cmdr. Malcolm L. Pratt. Since he believed that they would pick up some Japanese prisoners, Goettge also chose men from the intelligence division of the 5th Marines, including Captain Wilfred Ringer, First Sergeant Stephen A. Custer, and an officer who had worked in Japan before the war and was fluent in Japanese, Lieutenant Ralph Corey.

The patrol boasted other men who had already built a reputation among their fellow Marines for leadership and toughness. Twenty-two-year-old Sergeant Frank L. Few of Buckeye, Ariz., so impressed observers that reporter Richard Tregaskis later praised him in his famous 1943 book about the Solomons, Guadalcanal Diary. He wrote that the half-Indian was “vastly respected by the men because he is, as the marines say, ‘really rugged.’ This means he is a tough hombre, and Few certainly looks the part; he has fierce dark eyes, a wiry, muscular body, and he moves with the swift ease of a cat. A flashing white smile, sideburns and scraggly black beard and mustache only intensify the effect.”

Should they run into an awkward situation, the men knew they could also look to Sergeant Charles C. “Monk” Arndt and Corporal Joseph Spaulding. However, since no more than 25 men were to be removed from the beachhead, the additional intelligence officers selected by Goettge took the place of Marine riflemen originally assigned to the patrol. Later, when the fighting commenced, the officers would miss this handful of Marine riflemen.

That, however, stood in the future. As the 25 Marine riflemen and officers collected near the Higgins boat that would transport them by water from Kukum to their designation west of Point Cruz, their thoughts centered on a possible firefight. The fact that the patrol would now head out after dark, around 6 pm, a delay caused by Goettge’s last-minute changes, bothered only a few men. They would land, bivouac for the night, and then head out the following morning.

In the dark, though, confusion set in. From the sea, Goettge had difficulty sighting the correct landing area, and instead of hitting the proper sector, the boat came in too far east. As the Higgins boat approached land near the mouth of the Matanikau River, the boat’s engine made so much noise that the numerous Japanese soldiers in the area were alerted to the presence of the American squad, creating a perfect storm for the events of the “Goettge Patrol Incident” to unfold.

If that were not enough, when the boat hit a sandbar and forced the coxswain to reverse engines in an effort to inch off the obstacle, more sound reverberated through the jungle. To make matters worse, the Marines had to leap out of the Higgins boat and wade ashore on the west side of the Matanikau, precisely where they had been warned not to land.

Colonel Goettge led his men a short way toward the jungle but stopped before leaving the beach to establish a defensive perimeter. Goettge ordered most of the men to remain on the beach while the Japanese sailor, held close by a leash, led Goettge, Captain Ringer, and Sergeant Custer into the jungle toward the supposedly weary enemy soldiers.

The group disappeared into the foliage, but within minutes gunfire shattered the darkness. Goettge and the Japanese sailor slumped dead to the ground, while a wounded Sergeant Custer and Captain Ringer returned fire and scurried back toward the beach. As bullets whizzed around them and splattered into the sand, Ringer dragged the bleeding Custer out of danger, and the two safely returned to join their fellow Marines. For much of the night, while Dr. Pratt tended to Sergeant Custer and other injured men, the Americans fought a desperate battle to keep the numerically superior and well-hidden enemy at bay.

During a lull shortly after the fighting started, different men called out Colonel Goettge’s name to see if he might respond. When they heard no response, Sergeants Few and Arndt and Corporal Spaulding volunteered to crawl back into the jungle to rescue their commander. The trio searched around until they found Goettge, dead from bullet wounds to the head. Spaulding started back to the beach to bring up more help while Few and Arndt remained behind as cover.

In Spaulding’s absence the enemy closed in on Sergeants Few and Arndt. One Japanese soldier rushed Few’s position, and in the darkness Few mistook the soldier for an American. He shouted the password, but in turn received bayonet wounds to the body and leg. In the struggle, Few grabbed the rifle from his assailant and bayoneted him to death. He then picked up a pistol and killed a second Japanese soldier.

Few later explained the incident to correspondent Tregaskis, who included it in his book. “Just then I saw somebody close by. I challenged him, and he let out a warwhoop and came at me. My sub-machine gun jammed. I was struck in the arm and chest with his bayonet, but I knocked his rifle away. I choked him and stabbed him with his own bayonet.”

Few and Arndt were on their way back to the beach when Few spotted a Japanese sniper perched in the trees. He switched Sergeant Arndt’s pistol for his jammed machine gun, took careful aim, and killed the Japanese. A fourth enemy soldier rushed out of the jungle toward Few, who by then had fixed his weapon and was able to quickly dispatch the foe.

Captain Ringer established a tight defensive perimeter at the beach, but he knew that his outnumbered men could not last long in such an open location. The Japanese had the advantage of knowing precisely where the Americans were, while the Marines only had a vague idea where to shoot. So much machine-gun and rifle fire peppered the perimeter that it became only a matter of time before every man was either wounded or killed. Among those shot was Dr. Pratt, who was wounded while tending to another Marine. Pratt later died from his injuries.

Since he lacked a radio, Captain Ringer had to improvise if he were to send word back to Kukum that he needed help. During the melee, he turned to the most likely manner of attracting attention and ordered a corporal to rush to the water’s edge and fire tracers. Ringer hoped that the Marines back at Kukum, 41/2 miles away, would notice the illumination and dispatch a relief squad. The corporal fired three tracers skyward, but his effort was in vain. Although the Americans at Kukum spotted the lights, they had no idea what they might mean and thus did not send out any additional forces.

The Marines of the Goettge Patrol Incident Showed No Fear About Their Fate

Ringer next turned to volunteers who would try to make it back to Kukum and bring help. Sergeant Arndt, who had proven abilities as a scout on land and as a strong swimmer, agreed to remove most of his gear, head for the water, and swim the almost five miles back to Kukum. A wiry veteran, Arndt earned his nickname of “Monk” in 1939 during duty in Puerto Rico when he climbed a tree to retrieve a few coconuts. Tough in training and steadfast in battle, Arndt had gained a reputation as someone who could be relied on. Sergeant Few agreed with his selection and said, “If anyone can get through, it’ll be Arndt.”

Sergeant Arndt left around 1 am on August 13, struck by the fact that no one remaining on shore complained that they had not been chosen or showed any signs of fear about their fate. As Marines they knew their duty, and if that meant they had to stay behind and die, then so be it. Hopefully, Arndt could bring back help in time, but the likelihood was that the Japanese would close in for the final kill before reinforcements arrived. Arndt had his mission and they had theirs.

Because of heavy Japanese fire, Arndt slithered off the beach toward the sea “like a snake, on stomach, hands and knees, and I went like this just as far as I could without swimming at all. Out for about 30 yards.” As he approached the deeper water, Arndt forgot that he had not untied his shoelaces. He attempted to loosen his boots and slip them off, but the knots were too tightly bound by the water. He was able to remove his clothes, however, and naked except for socks, shoes, helmet, and a pistol crammed inside the helmet to keep it dry, Arndt plunged into the deeper water and headed toward Kukum.

Using the breast stroke to keep his helmet out of the water, Arndt drew fire when he crossed the sandbar upon which the Higgins boat had been stuck. He evaded that, veered farther from shore, then swam parallel to land.

“I’d go in to the beach once in a while and there was a lot of coral that I had to hold on to and I have scars yet on my hands and legs where I was pushing around the coral,” Arndt stated in a 1948 interview. “I was crawling over the rocks awhile and swimming awhile.”

Whenever a coral patch impeded his swimming, Arndt braved the razor-sharp edges and either walked or crawled over it. He then jumped back into the water, swam to the next coral outcropping, and repeated the process. In this manner, he slowly progressed toward help.

Occasionally, he turned toward shore to walk for a bit, but he had to be extremely careful lest he stumble upon a Japanese patrol. One time, as he walked along the shoreline, he heard a noise and saw someone running away. Arndt fired at the unknown individual and assumed he had hit him when he detected no further sounds of movement.

The trek back to Kukum proved exhausting, but whenever Arndt felt like stopping and resting, he thought of his buddies back at Point Cruz. As weary as he might be, they had to be in far worse shape, mentally and physically. “It’s just like a man is just exhausted completely and ready to give up and then I’d look back where the patrol was and see a tracer shoot up in the air and then I’d go on again. I was thinking about those men down there.”

Luck turned in Arndt’s favor when he came across a native boat beached along the shore. He waded toward the craft and noticed that one end had a number of bullet holes. Arndt nudged the boat offshore, jumped into the undamaged end so that the bullet-riddled end lifted out of the water, and paddled away with a plank that he found in the boat.

Arndt traveled more than two miles before he reached Marine lines, but his safety was far from guaranteed. Nervous sentries would be eager to shoot first and ask questions later, so Arndt had to be especially careful. His luck almost failed when a Marine guard challenged him and asked for the day’s password, but a weary Arndt could not think of it. Fearing that he would be shot, Arndt quickly yelled out a word he knew the Japanese would have trouble pronouncing, “million.” He figured the enemy could not correctly handle a word containing the double “l,” so he kept repeating the word until the sentry believed he was an American.

When Arndt sloshed ashore about 5:30 that morning, the other Marines stared at him as if they had seen a ghost. Arndt bled from coral cuts and scratches to most every portion of his body; in some cases the coral had sliced inches deep into the skin, even exposing the bones of his fingers. The stunned Marines wrapped a blanket around him and led Arndt away to give his report to superiors.

While Arndt worked his way back to Kukum, Captain Ringer and the rest near Point Cruz did their best to fend off the enemy. The Japanese cautiously crept closer as the night waned, and as they drew nearer their likelihood of killing a Marine increased. From more than 20 Americans, the numbers dwindled to less than 10. Sergeant Custer fell to gunfire, and the enemy approached so near to Sergeant Few that he could practically feel the muzzle-blast of their machine guns. Marines battled in the darkness, trying to guess where their enemy might be and fire in that direction. Normally, a rifleman shoots toward the flare of muzzle blasts, but as the Japanese had muzzle blast suppressors on their weapons, the Marines could not effectively respond. They had to maintain a steady volume of fire, hold off the Japanese, and hope that aid would come rushing in from Kukum.

Captain Ringer had no idea if Sergeant Arndt had safely reached American lines. The only information he had was that they heard gunfire farther down the beach shortly after Arndt left. Concluding that he could not assume that Arndt had succeeded, about one hour after he ordered Arndt away, he sent Corporal Spaulding on the same mission. Spaulding wished his buddies on the beach good luck, removed his clothes and shoes, splashed into the water, and swam east.

Like Arndt, he headed toward shore when exhausted to catch a moment’s breather. One time he spotted a fire and, thinking it was a group of Marines, went over to check it out. To his consternation, the soldiers turned out to be Japanese, but fortunately they failed to notice Spaulding, who carefully returned to the water and continued his odyssey. Spaulding safely arrived at Kukum about one hour after Arndt. As happened with Arndt, a jittery American sentry almost shot him before Spaulding convinced him he was a Marine.

The situation turned desperate at Point Cruz as dawn’s initial rays illuminated the beach. Only Captain Ringer and three others, including Sergeant Few, remained able to fight. Figuring that if they stayed on the beach they would certainly perish, Ringer led the three men toward the jungle in hopes of hiding. They advanced only a few yards before gunfire cut down a corporal. Ringer and another reached the tree line, only to be killed by a flurry of bullets. Sergeant Few spotted a Japanese soldier firing into Marine bodies, rose, took aim with his .45, and killed the enemy, but he realized that he was in an impossible situation. From the initial unit that left Kukum the day before, only Sergeant Few remained.

“The Japs Closed in and Hacked Up Our People. I Could See Swords Flashing in the Sun.”

If he had any chance to survive, Few had to leave immediately, for there was little he could do to halt the Japanese. As far as he knew, none of his fellow Marines still breathed, so he could accomplish nothing by staying in the area. While still under Japanese fire, Few stripped to his underclothes and dashed for the water.

After he swam far enough from shore to be out of the enemy’s range, Few looked back toward the beach, where he witnessed one of the Pacific War’s earliest atrocities involving Americans. Glancing through the distance, Few noticed the glare and flashes of descending swords. The survivor recoiled from the horror of what unfolded on the beach. “It was the end of the rest on the beach,” he explained to correspondent Tregaskis. “The Japs closed in and hacked up our people. I could see swords flashing in the sun.”

Few, sickened by what he saw, could not tarry in the water. From another portion of the beach a group of Japanese soldiers moved a machine gun to the shoreline in an attempt to reach the final American. Few quickly dove under the water and put more yardage between himself and the enemy, then altered his swimming direction to make it harder for them to guess his location. Finally, he moved far enough away to be safe from the dangers on land.

He still faced threats from the sea, however, as sharks heavily populated the waters surrounding Guadalcanal. He could do little about that hazard except continue swimming and hope for the best. Trusting that all would end up well, Few gathered his remaining strength and continued his long swim back to Kukum.

Around 8 am, an exhausted Few dragged ashore near Kukum after battling the waves and weariness for more than 41/2 miles. He was so tired from his ordeal that, like the two previous Marines, he could barely muster sufficient strength to answer a sentry. Evading this final flirtation with death, Few stumbled ashore to add his report to what Arndt and Spaulding had already divulged.

Angry Marine officers quickly organized a patrol to search for any surviving members of Goettge’s group. Company A, with two platoons from Company L, 5th Marines, and a light machine-gun section landed west of Point Cruz, erroneously thinking that Goettge had landed where he was supposed to. Company A advanced east along the coast, receiving enemy fire at the mouth of the Matanikau, while the other two platoons and the machine-gun section veered inland.

The two groups returned to Kukum after scouring the region. Some accounts claim both arrived empty-handed, while others, including the information provided by Private Donald Langer, one of the lead scouts, reported spotting a gruesome scene in the jungle—arms and legs protruding from the sand. Before a third group could be dispatched to investigate, heavy rainstorms hit the area and apparently swept the bodies out to sea.

Although the final disposition of the remains is in dispute, what cannot be argued are the consequences and effects wrought by the Goettge Patrol Incident, not only on their fellow Marines, but on all the military in the Pacific and on the people back home. For starters, the division lost most of its intelligence section in an apparently futile action that caused many Marine officers to be hesitant about talking to the press. The patrol should never have departed after dark, which handed the Japanese a huge advantage. Compounding the error, Goettge led his men into a dangerous area without knowing the strength of the opposition.

One Marine, Grady Gallant, said after the war that he and his buddies on Guadalcanal were stunned by the patrol’s mistakes. Marines were “shocked because we had fallen for such an obvious trap; shocked because headquarters had believed anything a Jap had to say; shocked and angry and sickened because the Japanese had been able to kill so many and suffer no deaths in return.”

“After This, ‘No Prisoners’ was an Unspoken Agreement.”

People on the home front reacted with disgust as well. Richard Tregaskis spread news of the incident when his book, Guadalcanal Diary, devoted one section to the patrol. A subsequent popular Hollywood motion picture of the same name contained one graphic scene showing a Marine at sea, based on Sergeant Few, turning back to watch the slaughter of helpless wounded Marines by sword-wielding Japanese. Men and women throughout the country obtained their first glimpse of the true horror of the Pacific War from this incident. (Read more about the stories and incidents that shaped the South Pacific inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

The Goettge Patrol had the most potent impact on the Marines in the Pacific. A unit of men who, in part, headed into the unknown to accept the surrender of supposedly starving Japanese, instead fell victim to a massacre. Rumors spread that the Japanese cut off the hands of one man and ripped out the tongue of another. Grady Gallant explained that he and his buddies were convinced the Japanese sailor deviously led fellow Marines to their deaths in a Japanese jungle trap “waiting for the innocent to follow the Judas goat to death.”

Marines angrily argued that if the enemy wanted a dirty war, they would get one, for the Marines would answer back in equal measure. The notion of “kill or be killed” rapidly spread throughout the Pacific, and according to Private Donald Langer, “After this, ‘no prisoners’ was an unspoken agreement.”

Every Marine unit entering the Pacific Theater knew the story of the Goettge Patrol. Marine Pfc. Eugene Sledge, who later wrote one of the most moving memoirs of the Pacific strife, With the Old Breed, related an incident in his book. When he asked a Marine veteran why the Goettge Patrol had been ambushed, the veteran said of the Japanese, “Because they’re the meanest sonsabitches that ever lived.” Sledge reported that soldiers felt true hatred toward the Japanese, in part because of the atrocities committed against the Goettge Patrol. He related that “at the time of battle, Marines felt it [hatred] deeply, bitterly, and as certainly as danger itself. To deny this hatred or make light of it would be as much a lie as to deny or make light of the esprit de corps or the intense patriotism felt by the Marines with whom I served in the Pacific….

“This collective attitude, Marine and Japanese, resulted in savage, ferocious fighting with no holds barred. This was not the dispassionate killing seen on other fronts or in other wars. This was a brutish, primitive hatred, as characteristic of the horror of war in the Pacific as the palm trees and the islands.”

The Goettge Patrol Incident had helped illustrate that the palm trees and beaches of the Pacific, once associated with fun and frivolity, would now be the scene of bloodshed and barbarism.

John Wukovits is the author of the book Pacific Alamo on the heroic defense of Wake Island. He is an expert on the war in the Pacific and resides in Trenton, Michigan.

Thanks for your report. Is it possible to pinpoint the landing spot relative to Point Cruz or the mouth of the Matanikau?

I hope reaches you in good health.

CJ

Another reader, former Marine, and military enthusiast here…the referenced site is one of the best so far, that references many aspects of the Battle for Guadalcanal, with photographs and other depictions. The Goettge Patrol fiasco is also well delineated.

Sergeant Frank Few was my Grandpa, i still vividly remember him telling me about this particular Goettge patrol when i was about 8 years of age. If the author of this article want’s a picture of my Grandpa to put in the article let me know.

W.Few. I would very much like to see photographs of your grandpa. Thank you.

If you won’t mind, I’d like to see a picture of gramps as well…I worked with many marines in Sicily, and have the upmost respect for them (even if I was a Navy guy).

As a Marine I would greatly appreciate a picture of your grandfather. God bless him and all the others.

Hi Jeric, Steve and Gabe

Dave Holland produced a recent presentation on the ill fated Goettge Patrol, there’s a photo of Frank Few in the presentation 3/4 the way in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w3pwY6g93vA&ab_channel=Guadalcanal-WalkingaBattlefield

Recent documentary History Channel on the Goettge patrol (first 10 minutes) https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x6jli90 you’ll see picture of Frank Few on the island part way in.

Thanks for sharing such a well written and researched article. Only recently am I, a member from a younger generation, beginning to understand the war in the Pacific and what it was like to be an American marine fighting the Japanese soldiers. Too much has been written about our European warfront and not enough about the most bloody American battles of the war on these remote pacific islands. In addition, while I can visit the beaches of Normandy and other battle grounds in France, it is almost impossible to catch a plane to Iwo Jima or the other remote pacific islands to feel what it was like to have fought for these now worthless islands. However, for war historians who desire to visit the actual battlefields, I strongly recommend a visit to Manila, The Philippines, where a short boat ride to the small island of Corregidor is available and the price includes an island tour which includes a visit to Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters. The tour was very inexpensive and only a short trip to Manila bay.

The hatred of the Japs mentioned was not limited to the marines. My father, TSgt Harley Woodley, USArmy Medical Services, was in charge of the x-ray unit of the 148th Army General Hospital on Saipan in 1945. The hospital was built in anticipation of receiving casualties from the planned invasion of the Japanese homeland. He saw many of the returning POW’s from the Japanese prison camps and could not talk about it without tears. He hated the Japs.

I worked with Frank Few in the 1970s when he was a TV news cameraman in Melbourne, Australia. As a 24-year old news reporter, I spent hundreds of hours sitting in news cars with Frank, never knowing his story. By that time, Frank was in his mid-fifties. It’s only in recent years I’ve begun reading of his incredible bravery during the Goettge Patrol in articles like this. By the time I knew Frank, he used to drink pretty heavily. I could never figure out why. Now I know. Frank was a quiet and unassuming guy, who always called me ‘little buddy.’ We had some good times on the road. My deep regret is that I didn’t know his story back then, and now, I’ll never get a chance to talk to him about it.

Hi Brad, Franks grandson here (from Melbourne Australia).

I urge you to read Geoffrey W. Roecker’s recently published book ” Leaving Mac Behind, The Lost Marines of Guadalcanal” Chapter 3 specifically. Geoffrey paints the harrowing scene here from a number of well sourced references. What the surviving 3 Marines wen’t through during the battle and the days following would have been extremely traumatising. You’re right, he could certainly drink, no doubt a coping mechanism from the trauma. He passed away 8th Feb 1993.

BTW, Grandpa named his favourite dog “Buddy” i guess this was in the early 80’s so perhaps you had an influence on him you may have never known…