By James M. Powles

The famed general of World War II, George S. Patton III, often spoke with pride of the military deeds of his forefathers. From an early age, Patton had been regaled with the exploits of the Pattons and their relatives from the War for Independence to the Civil War. These stories of courage and great deeds, of heroic men and mighty battles, greatly influenced the man who would dash his tanks across France.

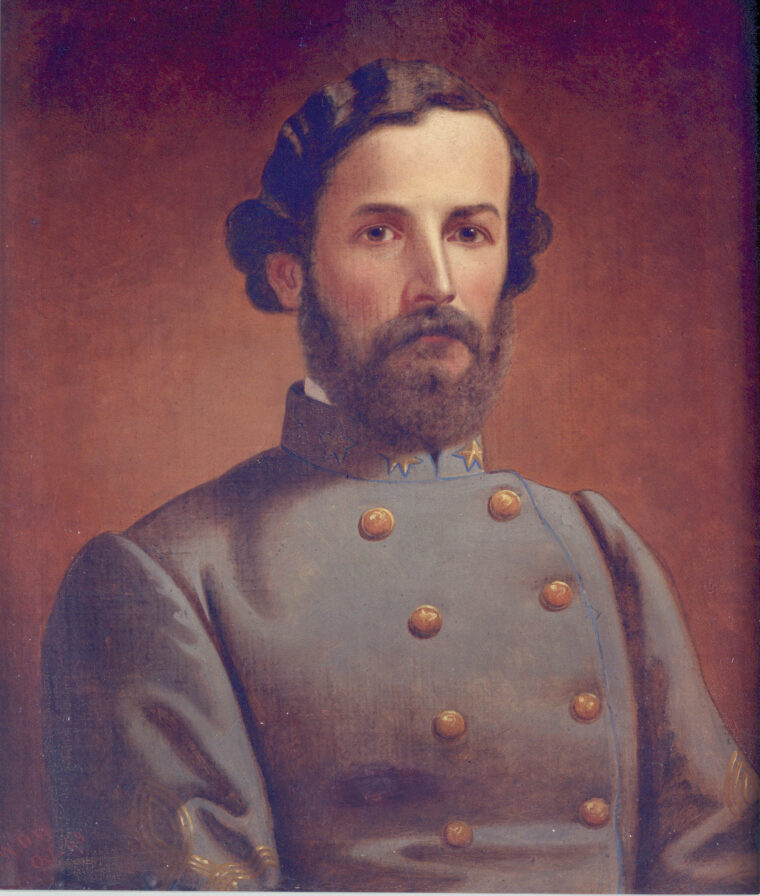

Of all the courageous men spoken of, none stood taller in the eyes of the young Patton than his dead grandfather, Confederate Colonel George S. Patton I. This was the man the younger Patton regarded romantically as a noble fighter, who had displayed great bravery and honor in battle and had met his end at the head of his troops. So who was this unheralded soldier of the Civil War that Patton knew only through stories, but who helped to inspire him to become one of the great generals of World War II?

George Smith Patton was born in Fredericksburg, Va., on September 26, 1833, to Peggy and John Patton. The Pattons had 12 children, but only nine lived to adulthood—eight sons and one daughter. Peggy Patton was of the Virginia plantation society and John, a states’ rights advocate and pro slavery, was a lawyer, politician, and slave owner. The Pattons were loyal Virginians and proud of their Southern aristocratic culture. When John Patton died in 1858, his spirited, strong-willed wife became the matriarch of the family and continued to raise their children in the manner to which they were accustomed.

The Late Blooming Patton Excelled as He Matured

John Patton realized early on that to maintain the Southern way of life he and his wife held so dear would eventually lead to secession and hostilities. He therefore prepared his sons for the future conflict by sending them to military colleges. George Patton, like three of his brothers, attended the Virginia Military Institute. At age 16 Patton entered VMI, where for the first two years he was academically in the middle of his class but was a leader in demerits. Maturing in his last year, Patton graduated in 1852 second out of a class of 24. He excelled in Latin, English, French, chemistry, and artillery tactics.

At VMI Patton impressed his classmates with his mild-mannered but responsible personality and genial wit. Upon graduation, the tall, slim, handsome young man with long brown hair was ready to make his way in the world. In the summer after graduation, Patton met 17-year-old Susan Thornton Glassell of Alabama, who was visiting friends in Virginia. A relationship blossomed and by the fall they were engaged. For the next two years Patton taught in Richmond while studying law. Although he found teaching difficult and eventually quit, he did better at his law studies and was admitted to the Richmond bar in 1855. In November of that year he and Susan were married. On their wedding night the couple headed for Charleston, Kanawha County, Va. (now West Virginia), where Patton had been offered a partnership in a small law firm.

At Charleston, a town of some 2,000 located in the Kanawha River Valley, Patton set up a successful law practice and became involved in local affairs. The deeply religious Pattons were well liked by the citizens of Charleston, and soon after they arrived Patton was affectionately given the nickname of “Frenchy” for the goatee he sported. On September 30, 1856, the Pattons had their first of four children, a son they christened George William Patton. Eleven years later George William had his middle name changed to that of his father, Smith. George Smith Patton, Jr., would later become the father of General George S. Patton of World War II fame. Also in 1856 George organized and became captain of a militia company called the Kanawha Minutemen, to which he devoted much of his time.

War on the Doorstep

Although Kanawha County held the fewest slaves of any county in Virginia—and of these most were domestic servants—George followed his father’s beliefs and soon became a passionate supporter of secession. After John Brown’s invasion of Harper’s Ferry in the fall of 1859, Patton’s militia company changed its name to the Kanawha Riflemen and stepped up its drilling. Patton, feeling that war was just around the corner, devoted himself increasingly to his militia company at the expense of his law practice. With the firing on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, what Patton believed was coming and had prepared for finally arrived—the country was at war. When Virginia seceded from the Union, the Kanawha Riflemen became Company H of the 22nd Virginia Infantry Regiment.

Besides George, six other Patton boys would go off to fight for the Confederacy. John Mercer (1826-1898) would become the commander of the 21st Virginia, but had to resign in August 1862 owing to poor health. Isaac William (1826-1890), who had moved to New Orleans before the war, would lead a Louisiana regiment and be captured at Vicksburg. George’s closest brother, William Tazewell (1835-1863), would lead the 7th Virginia and be killed at Gettysburg during Pickett’s Charge. Hugh Mercer (1841-1905) became an officer in his brother’s 7th Virginia, while teenage brother James French (1843-1882) became an officer with George in the 22nd Virginia. The last Patton to serve was William Macfarland (1845-1905) who, as a cadet at VMI, would take part in the battle of New Market. The only brother not to serve was the oldest, Robert (1824-1876), an alcoholic former naval officer.

Patton first tasted combat on July 17, 1861, only 20 miles down the Kanawha River from Charleston, at a place called Scary Creek. Recently commissioned a lieutenant colonel in the Confederate Army, Patton commanded some nine hundred men who were part of a force under Brig. Gen. Henry A. Wise that was attempting to stop a Union push up the Kanawha Valley. The Federals were part of Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s assault into western Virginia from Ohio. Late into the battle, while trying to rally retreating troops in the center of the Confederate line, Patton was struck by a minie ball in the right shoulder, shattering the bone in the upper arm and throwing him from his horse.

Patton Refuses Amputation at Gun Point

He was carried to the rear where he was told that his arm needed to be amputated. Patton adamantly refused and pulled out his pistol to emphasize his point. He kept his arm, but never regained full use of it. Although the Confederates had won the battle, they were later forced to retreat from the Kanawha Valley. Unable to be moved because of his wound, Patton was left behind and captured. A few weeks later he was paroled and went home to recuperate.

After spending eight months at home impatiently waiting to get back into the war, Patton finally received word that he had been exchanged. Although he had only partial use of his right arm and could not raise it above his head, he returned to the 22nd Virginia as its commander. On May 10, 1862, Patton saw action again when he led the 22nd Virginia in an attack against a Union regiment at Giles Court House, Va., during Brig. Gen. Henry Heth’s campaign against Union forces trying to cut railroad lines in southwestern Virginia. The Confederates were victorious, but Patton again was wounded, shot in the belly.

Patton was laid against a nearby tree and, fearing that he was dying, he began writing a farewell note to his wife. General Wharton, his brigade commander, rode up and asked him how he was. George answered that he believed the wound was fatal. According to Patton’s son, George William, “Gen. Wharton dismounted and asked if he could examine the wound. He stuck his unwashed finger into it and exclaimed, ‘What is this?’ as his finger hit something hard. He then fished around and pulled out a ten dollar gold piece. The bullet struck this and had driven it into his flesh, and glanced off.” The bullet had struck a $10 gold piece that his wife had put into a money belt she had made and given him just before he left to rejoin his regiment. (In another version of this incident, it is General Heth, not Wharton, who finds the gold coin.)

Saved by a $10 Gold Piece

Thanks to the thoughtfulness of his wife, his life had been saved; however, although the wound was not serious, he developed blood poisoning and had to return to his family, now living in Richmond, to recuperate. While at Richmond, he learned that he had not been properly exchanged in March. For honor and to avoid being executed if captured again, Patton was forced to remain out of the war until he could be properly exchanged.

After waiting for what seemed like an eternity but was only a few months, Patton was finally exchanged. He rejoined the 22nd Virginia at Lewisburg, Va. His regiment was now part of the First Brigade, under Brig. Gen. John Echols, in the Army of Southwest Virginia. Because Echols suffered from heart disease and was frequently absent, Patton regularly took over command of the brigade. In the fall Patton’s regiment took part in the campaign to chase the Federal forces out of the Kanawha Valley and retake Charleston, which the Confederates had lost the year before. The drive was successful, but less than a month later the Confederates were driven back to Lewisburg, where they set up camp for the winter.

In the spring of 1863 the Army of Southwest Virginia began operations with a raid into the Union-controlled mountainous region of northwest Virginia (now West Virginia). The purpose of the raid was to impede the New State Movement in the region (the creation of a new state in western Virginia loyal to the Union which, of course, eventually succeeded); the destruction of the rail lines of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and other Union property; and to forage for food, clothing, and other badly needed supplies. Patton and his regiment were part of Brig. Gen. John Imboden’s force, one prong of the two-prong raid. Leaving camp at Shenandoah Mountain on April 20, Imboden’s raiders roamed slowly through the region capturing wagon loads of supplies, livestock, and horses before returning to the Shenandoah Valley. Patton, proud of how his regiment had performed, noted that 40 of his men marched the entire 400 miles barefooted.

A Full Display of Patton’s Talent in Battle

In August, Union Maj. Gen. William Averell, a friend of George’s before the war, led 3,000 men against Lewisburg. On the 26th, at Dry Creek, Averell’s cavalry force collided with the First Brigade under Patton. After two days of hard fighting, Averell was beaten back. The victory at Dry Creek showed Patton’s ability to command troops in battle to the fullest.

Averell, however, was to get his revenge against Patton in November, when he confronted him at a place called Droop Mountain and where Averell’s force of 5,000 cavalry defeated Patton’s 1,700 men. Patton was forced to retreat, allowing Averell to occupy Lewisburg for a few days before the threat of a counterattack forced the Union cavalrymen to leave. At the time of the battle, Patton’s family was living in Lewisburg. His son William vividly recalled seeing the defeated troops passing through Lewisburg and later wrote: “Late in the night my father came by with the last of the rearguard and stopped to tell us goodbye and give my mother a letter for General Averell asking him to see that we were not bothered.” The next morning Susan took the letter to Averell who, honoring the request from his old friend, posted a guard at the Patton home.

Patton’s finest hour came the following year at the Battle of New Market. Patton’s regiment was part of a small army hastily assembled under Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge to counter a Union thrust under Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel up the Shenandoah Valley toward Staunton. (Because the Shenandoah River runs south to north, the Union thrust up the valley was actually going in a north to south direction.) The Confederates, being vastly outnumbered, had to call upon 247 cadets from VMI as reinforcements. One of the cadets who immortalized the VMI Corps of Cadets that day was Patton’s youngest brother, William Mercer Patton.

The two sides clashed on the Valley Turnpike at New Market on May 15, 1864. In the ensuing battle the Confederates made a heroic stand against superior Union forces and won the day. During the latter stage of the battle, Patton, who for all practical purposes was commanding the First Brigade for the ailing Echols, was defending the right against Union cavalry attempting to outflank the Confederate line. When the cavalry broke through the left of his line, Patton quickly wheeled his 22nd Virginia and the 23rd Virginia of Lt. Col. Clarence Derrick to either side of the gap, catching the Union cavalrymen in a deadly crossfire. With the help of several pieces of artillery, the Confederates decimated the Union horsemen, forcing many to surrender and the rest to retreat in panic.

Promoted to Brigadier General

According to historian William C. Davis, “The principal architects of the triumph [at New Market] were Patton’s 22d Virginia, to a lesser extent Derrick’s 23d Virginia, and Breckinridge with his magnificent guns. Patton’s and Derrick’s men, spread thin, successfully withstood that most terrifying of assaults to an infantryman, a mounted charge. More than that, they threw it into disarray, turning it into a rout.” New Market proved without a doubt that Patton was an outstanding and resourceful leader. A week later, when his poor health forced Echols to give up his command permanently, Patton was given command of the brigade—a promotion he rightly deserved. Patton was also recommended for a promotion to brigadier general.

Soon after the battle at New Market, Breckinridge’s army was rushed east to help Robert E. Lee stem Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s advance on Richmond. Patton’s brigade joined Lee’s forces at the crossroads hamlet of Cold Harbor, only eight miles from the Confederate capital, on June 2. Hastily building defense works through the night, Patton and his men were barely ready when at 4:30 am Grant launched a full-scale attack against the entrenched Confederates. Grant was repulsed, losing nearly 7,000 men in half an hour. One Confederate general said, “It was not war, it was murder.”

“It Was Not War, It Was Murder.”

Immediately after the battle Patton’s brigade headed back to the Shenandoah Valley to join Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s army. The Union forces were again advancing south, and Early had been tasked with countering this new threat. After pushing the Federals out of the valley, Early continued on through Maryland to the outskirts of Washington. Patton’s brigade was one of the first Confederate units to reach the city on July 11. Finding the city’s defenses heavily reinforced the next morning, Early called off an assault on the city and that night headed back to the Shenandoah Valley.

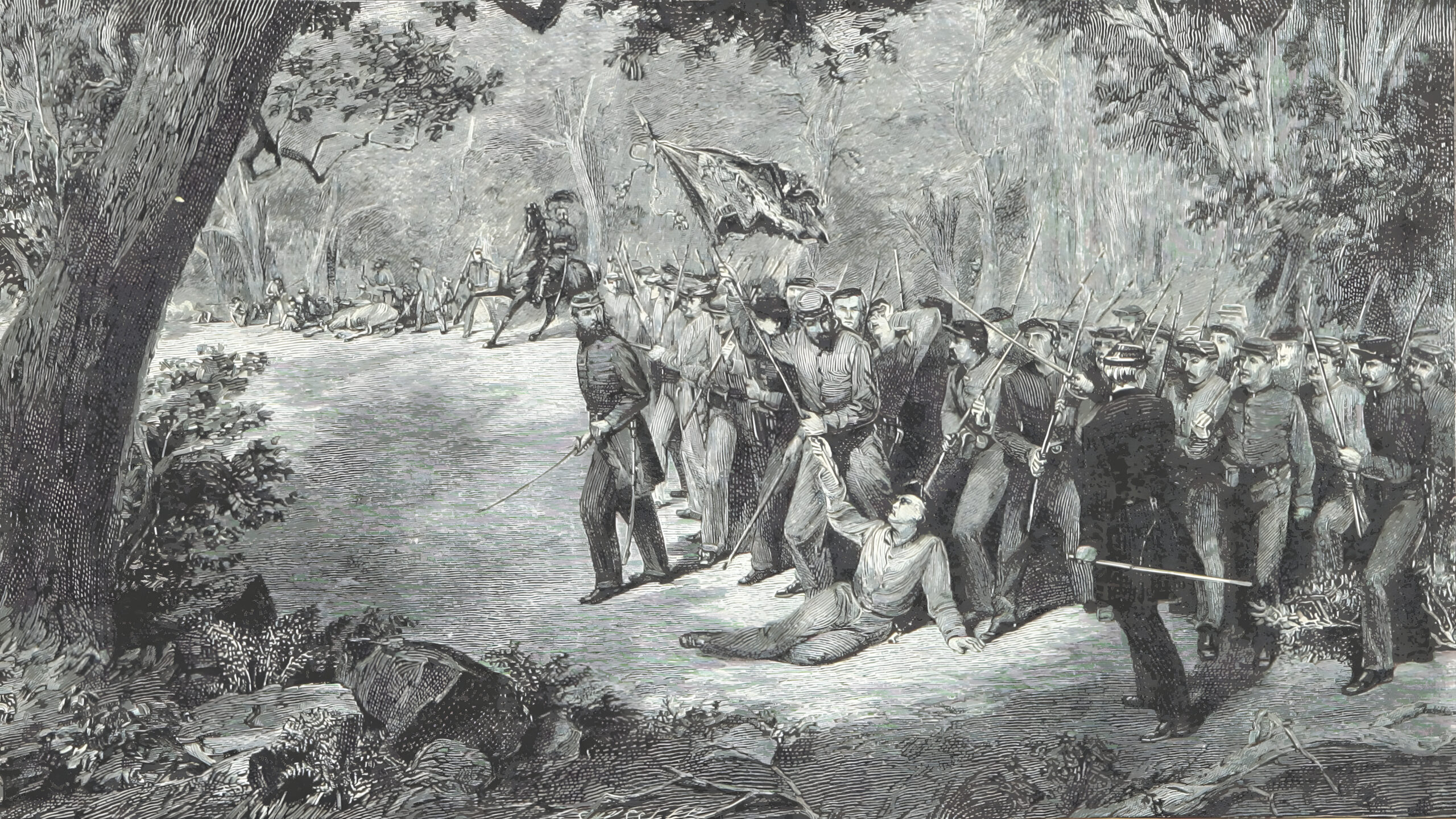

In response to Early’s incursion into Maryland and the threat to Washington, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan was ordered to deal with Early and lay waste to the Shenandoah Valley. The two sides clashed on September 19 at Winchester, Va., in the Third Battle of Winchester. Greatly outnumbered, the Confederates could not stand up to the Union’s lightning attack and were defeated. Early lost one-third of his army and Patton’s brigade lost half its men. But that was not all that Patton’s brigade lost that day; it lost its commander as well.

A Second Refusal for Amputation and the Loss of a Great General

Around 2 pm, as the Confederates were being pushed back, Patton was making a stand on the left of the line against a determined attack by Sheridan’s cavalry. It was then that he was wounded. Robert H. Patton, in his book on the Patton family, described the event: “He was standing in his stirrups on a Winchester street when an artillery shell exploded nearby and sent an iron fragment into his right hip. He’d been trying to rally his men, who were in full retreat before onrushing Yankee cavalry….” He was taken to a nearby house and later captured. Amputation of his right leg was recommended, but as he had done after Scary Creek, he refused. Within a few days gangrene set in and he ran a fever. On September 25, 1864, he died of his wound. (Claims have been made that at the time of Patton’s death a commission as a brigadier general was en route to him. According to Terry Lowery, a 22nd Virginia historian, there is only sketchy evidence to support this and no solid documentation has been found. However, Patton had been recommended for the promotion on several occasions.)

Patton’s wife Susan, reading about her husband’s wounding in the newspapers, hurried to Winchester; sadly, by the time she arrived, he had passed away and been buried. Rather than move her husband’s body to one of the family plots in Richmond or Fredericksburg, she left it interred at Winchester. Some 10 years later Patton’s younger brother, William Tazewell, who was killed at Gettysburg, was moved to Winchester, and he and George were reburied in a simple grave.

The year after the war ended Susan and her four children joined her brother in California. In 1870 Susan married George’s close friend and first cousin George Hugh Smith, who like George had served the Confederacy, commanding two Virginia regiments. Smith adopted the Patton children and lovingly brought them up as his own. In 1883 Susan died after suffering from cancer for several years. Patton’s oldest son, George S. Patton II , attended VMI like his father but did not pursue a military career. He did, however, keep the memory of his father’s military service alive through the stories he told his son, General George S. Patton III.

I am writing a biography on General William Woods Averell (1832-1900) who G. S. Patton Sr. fought at Dry Creek, Droop Mountain and Third Winchester in 1863 and 64.

This article and others mention that Averell and Patton were friends before the war. I would like more details to confirm this. To my knowledge from ten years studying Averell ( who is my 3x Great Uncle), I can not figure out how their paths crossed in the 1850s. It seems they were no where near each other. I would love to know more.

Ralph Rhodes