by Roy Morris, Jr.

Twenty-four hours earlier, Grazzi had hosted a gala reception for Metaxas and Greece’s figurehead king, George II, at the Italian consulate following a performance of Giacomo Puccini’s opera, Madame Butterfly. There, he had toasted Greek-Italian friendship with fine French champagne and a large cake bearing the words “Long Live Greece.” The new message he had been ordered to deliver to Metaxas at the behest of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was far less cordial. Although cloaked in the usual diplomatic pleasantries and written, as was still the custom of foreign ministries throughout the world, in formal French, the note’s underlying meaning was clear: Italy was invading Greece. The Greco-Italian War was on its way. The only question was how the vastly outnumbered Greeks would respond. (Learn all about these and other conflicts of the twentieth century, from the infamous to the lesser known, by subscribing to Military Heritage magazine.)

Grazzi waited silently for the answer as Metaxas, clad only in a nightshirt, a flowered dressing gown, and slippers, read over the message while sitting on the sofa in his trinket-laden study. The 69-year-old Metaxas, a former general, was not a well man. A lingering throat infection had sapped his strength, and the day before he had received word from his doctor that he would have to undergo a dangerous operation to determine the underlying cause of the infection. He had been sound asleep when Grazzi arrived. Now, however, he was wide awake. His hands trembled slightly as he read the document, and behind his reading glasses his dark eyes glistened with tears.

“Alors, C’Est La Guerre”

The gist of the message was unmistakable. Italy—already at war with Greece’s ally Great Britain as part of Italy’s “Pact of Steel” with Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany—was demanding the right to occupy various strategic points within Greece “for the duration of the war in the Mediterranean.” The ultimatum accused Greece of allowing the British Royal Navy to use her territorial waters and ports to attack Italy, as well as permitting the buildup of British secret forces on Greek islands. “These provocations,” the ultimatum declared, “can no longer be tolerated by Italy…. The Italian government demands that the Hellenic government shall not pose any resistance to this occupation. Should the Italian forces meet with resistance, such resistance will be crushed by force of arms.”

Metaxas looked up from the document. “Alors, c’est la guerre (So, this is war),” he said in French. Not necessarily, Grazzi urged. “If you order your troops to let our forces enter freely, then—” Metaxas cut him off. “There is no need for you to continue,” he said. “For one thing, I will never issue such an order, and for another, your ultimatum is expiring in almost one hour. There is no time. I could not make a decision to sell my own house on a few hours’ notice. How do you expect me to sell my country?” Then Metaxas, with a fine sense of drama, switched to his native Greek to make his formal reply to the Italian demands. “Ochi,” he snapped. That single word—“No”—would soon become the battle cry for millions of Greek patriots. It was also an accurate assessment of Italy’s military prospects on the Balkan Peninsula, although it would be some weeks yet before that forecast would be fully proven.

Preparing for the Greco-Italian War: Italy Encroaches Upon Greece

In many ways, Metaxas was an unlikely figure to rally Greek resistance against the Italians. “If in all Greece there was a single man who really had a feeling of affection for Italy, that man was John Metaxas,” Grazzi said later. A fascist himself, he had ruled Greece for the past four and a half years, having persuaded the weak-willed King George that the only way to face the mounting threat of communism within the country was to install a dictatorship, with Metaxas himself at the head of the government. Since then, the decidedly unmilitary-looking prime minister had instigated a milder, if still ruthless, form of fascism as it was currently being practiced in Italy and Germany. His soldiers had adopted the familiar stiff-armed salute, and Metaxas had created a secret police modeled on the dreaded Nazi Gestapo. A national youth group, the Neolia, or EON, imitated the larger countries’ pure-bred youth movements, marching stiff-legged down city streets and singing bloodcurdling songs of conquest. At the same time, Metaxas had instituted total censorship of the national press, banned the works of Plato and other “subversive hymns to democracy,” and exiled enemies of his regime to out-of-the-way islands. Although he was not a murderous despot like Hitler and Mussolini, he was nevertheless a despot.

In many ways, Metaxas was an unlikely figure to rally Greek resistance against the Italians. “If in all Greece there was a single man who really had a feeling of affection for Italy, that man was John Metaxas,” Grazzi said later. A fascist himself, he had ruled Greece for the past four and a half years, having persuaded the weak-willed King George that the only way to face the mounting threat of communism within the country was to install a dictatorship, with Metaxas himself at the head of the government. Since then, the decidedly unmilitary-looking prime minister had instigated a milder, if still ruthless, form of fascism as it was currently being practiced in Italy and Germany. His soldiers had adopted the familiar stiff-armed salute, and Metaxas had created a secret police modeled on the dreaded Nazi Gestapo. A national youth group, the Neolia, or EON, imitated the larger countries’ pure-bred youth movements, marching stiff-legged down city streets and singing bloodcurdling songs of conquest. At the same time, Metaxas had instituted total censorship of the national press, banned the works of Plato and other “subversive hymns to democracy,” and exiled enemies of his regime to out-of-the-way islands. Although he was not a murderous despot like Hitler and Mussolini, he was nevertheless a despot.

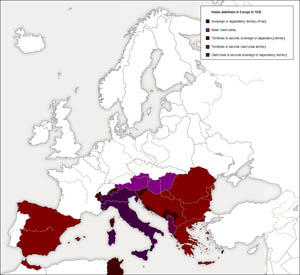

But in his way Metaxas was also a patriot, and he had been keeping a wary eye on Italy ever since Mussolini’s legions had occupied neighboring Albania in April 1939. Like most Greeks, Metaxas was aware—Mussolini said so, again and again—that the Italian strongman believed he had an “outstanding account” to settle with Greece over the murder of several visiting Italian diplomats in 1923 during an ongoing territorial dispute concerning the Greek-Albanian border.

In recent months, the Italians had committed a number of carefully calibrated provocations against Greek targets as a way of testing the smaller nation’s resolve. Italian bombers had attacked Greek ships and coast guard stations, and an Italian submarine had torpedoed the Greek destroyer Helle as she lay anchored off the island of Tenos during one of the country’s holiest days, the Feast of the Assumption. Thirty religious pilgrims had been killed or wounded during the attack.

At the same time, the Italian press had inflated the murder of an obscure Albanian murderer, rapist, and cattle-rustler named Daut Hoggia into an international incident. Hoggia, said the Italians, was “a man animated by great patriotic spirit” who had been killed by Greek agents while attempting to liberate the Tsamouria region of Greece for his fellow Albanian countrymen. In actuality, Hoggia had been killed by two other Albanian bandits during a quarrel. Publicly, Metaxas ignored the Italian provocations, but secretly he began mobilizing four divisions of troops, two of which were already in place on the Albanian border. So secret was the mobilization that the Greek public, to say nothing of the Italian Embassy, did not even realize it was taking place.

Dissent Among Italian Ranks

While the Greek forces were busy mobilizing, the Italian high command was busy arguing. The overall blueprint for the invasion of Greece, code-named Contingency G, had been worked and reworked for the past three months, and still there was no final decision on strategy, tactics, or primary objectives. The confusion reflected the indecisive and mercurial Mussolini himself, who sometimes changed his mind on a subject five times in 15 minutes.

Like his idol, Adolf Hitler, Mussolini fancied himself a brilliant military strategist. But unlike the Führer, who had his own limitations as an army commander, Il Duce had not won the Italian equivalent of two Iron Crosses for heroism. The closest Mussolini came to duplicating Hitler’s valorous World War I service was to be struck by shrapnel while observing the demonstration of a new mortar by his own comrades in the Italian Army. One fellow soldier said—apparently with a straight face—that the future dictator “wasn’t much under fire.”

As commander in chief, Mussolini presided over a quarrelsome group of generals and advisers, including most particularly his son-in-law, Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano. Arrogant, bombastic, and ambitious, the 35-year-old Ciano had married Mussolini’s eldest daughter and favorite child, Edda, 10 years earlier and thereafter had risen swiftly in the halls of Italian government. As a favored kinsman, Ciano naturally had Mussolini’s ear in a way that the other members of the inner circle did not. On the subject of Greece, Ciano was both hawkish and dangerously overoptimistic. He wanted a “little war” in the Balkans to establish Italian domination of the region and to checkmate the spreading German presence, begun with Hitler’s unopposed occupation of Bulgaria earlier that same month. An invasion of Greece, Ciano believed, would be “useful and easy.”

Over the objections of a majority of the general staff, called the Supermarina, Ciano convinced Mussolini to attack. And despite the fact that a previous battle plan had estimated that it would take at least a year and 18 full divisions to successfully bring off such an invasion, Mussolini decided in mid-October to attack in two short weeks. To make matters worse, General Visconti Prasca, commanding the Italian forces in Albania, would have less than one-third that number of divisions with which to attack. Nevertheless, Il Duce was adamant. “Dear Visconti,” Mussolini wrote on October 25. “Attack with the greatest determination and violence. The success of the operation depends above all on its speed.” Prasca, who had literally written the book on such an operation—he had titled it Lightning War—seemed like a good choice to lead the attack. Events would soon prove otherwise.

Three days later, at dawn on the 18th anniversary of Mussolini’s triumphant “March on Rome,” Prasca did as he was told. Even before the three-hour waiting period on the Italian ultimatum had run out, the forward elements of Prasca’s 100,000-man army began streaming across the Greek-Albanian border. At his villa in Rome, a poised and confident Mussolini waited patiently for the inevitable announcement of victory, entirely convinced that his people would welcome joyously the news of the invasion. “I shall send in my resignation as an Italian,” he told Ciano, “if anyone objects to our fighting the Greeks.”

Hitler Continues to Work on Franco

But if the Italians were happy to learn of the invasion, another European people—or at least their leaders—were not. Adolf Hitler had already spent a frustrating last few days trying fruitlessly to convince Spanish dictator Francisco Franco to enter the war on the Axis side. Franco, whose rise to power in Spain had been aided materially by Hitler’s air power and steady stream of supplies, did not think the timing was right for a new war, coming as it did so soon after his own country’s brutal civil war.

To Hitler’s frank astonishment, Franco refused to help. “I would rather have three or four teeth yanked out than go through such an interview again,” Hitler said after his final nine-hour meeting with Franco on the Spanish-French border. He had just departed by train for Berlin when he received word that Mussolini had invaded Greece. “How can he do such a thing?” Hitler raged. “This is downright madness. If he wanted to pick a fight with poor little Greece, why didn’t he attack in Malta or Crete? It would at least make some sense in the context of war with Britain in the Mediterranean.”

Ordering his train to turn around and head for Italy, Hitler and his bone-weary staff arrived at the train station in Florence on the morning of October 28. Mussolini and a 60-man band were waiting for him. On Il Duce’s signal, the band began playing a stirring version of the Italian Royal March, then hurriedly realized their mistake and switched to the German national anthem. Hitler, smiling grimly, cracked open his compartment window as Mussolini strode down the side of the train to meet him. “Führer,” he cried, “we are on the march! Victorious Italian troops crossed the Greco-Albanian border at dawn!”

That was the last thing in the world that Hitler wanted to hear. His own carefully thought-out blueprint for world conquest called for one more year of peace in the Balkans while he completed his buildup for a massive invasion of the Soviet Union in the spring of 1941. Nothing must interfere with the flow of oil, aluminum, lead, copper, chrome, tin, and other raw materials from the Balkans. That was the whole reason he had recently proposed a Tripartite Pact with Romania, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia, the three countries directly bordering Greece.

A Pig’s Mess

Now, in a stroke, Mussolini’s Greco-Italian War had destabilized Germany’s entire southern flank—and all without a word of warning. With surprising restraint, Hitler assured the beaming Mussolini that Germany would fully support him in his venture, although privately the Nazi leader murmured to his staff that the Greek invasion was nothing less than a schweinerei—a pig’s mess. Ciano, at Mussolini’s side, noted in his diary: “We are attacking in Albania and talking in Florence. In both places things are going well. In spite of the bad weather, the troops are advancing rapidly, though air support is lacking. In Florence the talk is of great interest and shows that German solidarity has not ceased.”

As usual, Ciano was too optimistic. Hitler was furious and immediately began reinforcing the 600,000 German troops already stationed in Romania for a possible Greek invasion of his own, should Mussolini’s “pig’s mess” live up—or down—to its name. Worse yet, the initial Italian advance was not going well at all. Torrential rainfall had drenched the region in the two days preceding the jumping-off point of the attack, turning previously dry stream beds into raging rivers and reducing dirt roads to muddy swamps. General Francesco Rossi, sent from Rome to inspect the front lines on the eve of the invasion, recommended that the advance be postponed. “Atmospheric conditions particularly adverse without expectation of early improvement,” he telegraphed Mussolini. “Supply and movement extremely difficult. Conditions for air force prohibitive. Bad weather hampering unloading of ships.” He advised that Prasca, commanding the invasion, be allowed to wait until the weather cleared. But Mussolini, who set great store in overt displays of symbolism, liked the notion of attacking on the anniversary of his grandiose “March on Rome.”

Nor did Prasca want to wait. As a comparatively new army commander, he was still low on the overstuffed list of Italian generals, and he was afraid that any delay in the Greek invasion would result in his being replaced by a more senior general. Mussolini deliberately played on Prasca’s fears, telling him disingenuously: “You know, and if you do not I am telling you now, that I have opposed all attempts to take your command away from you on the eve of the operation. I believe that events, and above all your actions, will justify me.”

With Mussolini’s veiled warning fresh in his mind, Prasca commenced the invasion as planned, at 5:30 am on October 28. Moving in total darkness through the icy rain, three columns of Italian troops began the assault. On the Italian left, the 11,000-man Julia Division, under Prasca’s direct control, headed toward the towering Smolikas Mountain, nearly 9,000 feet high, en route to the village of Metsovon and the critical Larisa-Yanina road. The division was comprised of tough Alpine fighters who were used to fighting at high altitudes. Despite the freezing weather, which caused the soldiers’ sodden puttees to grip their legs like pails of concrete, the division broke through the advanced Greek positions and pushed up the Aoos Valley in northwestern Greece.

Greece Prepares a Counterstroke

In the center, the Ferrara and Centauro Divisions, with 17,000 men between them, struck for Yanina. Some 3,500 Albanian volunteers accompanied the advance. Greek minefields and artillery fire slowed their progress. Farther south, on the Italian right, the Siena Division captured the village of Filates, crossed the raging Thiamis River, and swung north to encircle the Greek position at Yanina. Italian air superiority was rendered completely useless by the terrible weather conditions, which also forced the cancellation of a planned amphibious assault on the island of Corfu off the west coast of Greece.

For four days the Italians slogged eastward, laboriously crossing streams and rivers swollen twice their size and pouring with yellow mud, broken tree trunks, and the sodden carcasses of drowned sheep and other animals. On November 1, the weather suddenly cleared, and Ciano, who had come to Albania to observe the fighting, ordered a “slap-up bombing raid” on Salonika, in Macedonia, to divert Greek attention from the west. The bombing raid was a failure—poorly briefed pilots came close to wiping out a building full of Italian nationals who were waiting in Salonika for their forced repatriation—and the clearing skies permitted the skilled Greek artillery to begin shelling the Italian positions. Prasca, who had airily predicted on the eve of the invasion, “Greeks don’t like to fight,” soon had occasion to eat his words.

On November 2, Italian forces in the Julia Division captured Vovossa. It would prove to be their deepest penetration into Greece. Already there were signs of disintegration and disorganization within the Italian ranks. General Quirino Armellini of the Supermarina, on hand to observe the invasion, complained of “utter chaos” within the high command, which he attributed to the generals’ ill-advised tendency to operate on the principle, “First we’ll make war and then we’ll see.”

Ciano reported back to Mussolini, “There are complaints here about the ill will of the General Staff, which did not do all it should have done in preparation for the operation.” Specifically, Ciano pointed to Italian Chief of Staff Pietro Badoglio, who he said had undercut the offensive from the start, since he “was convinced that the Greek question would be solved at the conference table.” Mussolini, however, professed himself to be “satisfied with the development of operations in the first phase,” and Prasca assured him, “The Greeks have put up little resistance or have run away, even leaving tables laid and hot food behind them.”

But while Prasca was busy congratulating himself on his success, Greek General Alexander Papagos was preparing a swift and audacious counterstroke. On the morning of November 1, even as Mussolini’s air force was ineffectually bombing Salonika to keep the Greeks pinned down in Macedonia, Papagos launched a sudden attack across the Devoli River in southeastern Albania. Catching a battalion of the Italian 83rd Regiment as it was moving into line, the Greeks opened a gap in the enemy front. Advancing over Mount Morova and other precipitous hillsides on roads cleared of snow with the help of peasant women from nearby villages, the hardy Greeks infiltrated Italian positions all along their left flank, creating absolute consternation within the Italian camp.

Before the invasion began, Prasca had been assured that the Macedonian sector would remain quiet while he advanced into Greece from the west. But General John Pitsikas’s three divisions forced back the Italian 9th Army in wild, rocky terrain that was largely inaccessible to tanks, trucks, or the favorite Italian light transport, the motorcycle. Meanwhile, Greek mountain cavalry, riding small, agile horses accustomed to the most difficult footing, carried out lightning-quick sorties against the suddenly besieged enemy. On November 4, the crack Albanian Tomor Battalion was counterattacked in the Lapishtit Mountains and driven down the sheer face of the elevation. Italian carabinieri tried to intervene to stop the rout, at which time the panic-stricken Albanians began firing at them, too. Only 120 of the 1,000-man Albanian battalion remained in place when the shooting was over.

Italians Withdraw in Depth

With their backs literally against the wall—or at least the mountains—the Italians along the Macedonian front dug in and awaited reinforcement. Meanwhile, the Siena Division’s offensive in the south bogged down between Policastro and Kalpaki, where the Greek defenses held firm. In the middle of the Italian line, the Julia Division was in danger of being cut off from either wing by rapidly circling Greek troops.

The original Italian battle plan had called for a continuous advance on all fronts, but General Gabriele Nasci, commanding the XVI Army in the north, reported ominously that owing to “the aggressiveness and mobility of the Greek troops facing me as well as the strong support they have so far had from their artillery and mortars, it is not possible to make contact with the Julia Division.” He ordered the division to withdraw to Konitsa and wait for help. Under intense machine-gun and artillery fire from Greek soldiers and civilian volunteers who had also rushed to the front, the Julia Division fell back in near disarray.

Making matters worse, the notoriously fickle Balkan weather changed again. Rain turned to sleet and then to snow, and the temperature plunged to several degrees below zero. A biting north wind made it seem even colder, if that was possible. Thousands of troops on both sides, ill prepared for the brutal weather, suffered severe frostbite. Weapons froze up and would not fire; uniforms became as stiff and brittle as parchment paper. At night, groups of shivering men dug deep holes and slept together, piled like cordwood beneath their blankets. During the day, some Italians took to killing their pack mules and stuffing their helmets with the dead animals’ steaming brains. Others urinated on their hands to unstiffen their fingers.

On November 14, the Greeks began a full-scale offensive all along the line. By this time, Prasca had been relieved of command and replaced by General Ubaldo Soddu, an eccentric dilettante who amused himself by composing elaborate musical scores for imaginary movies. Soddu reluctantly decided on November 19 to begin a “withdrawal in depth”—in effect conceding all the territory the army had gained during the first three weeks of the campaign.

Back in Rome, Mussolini urged Soddu not to rush matters, but three days later the Italians began falling back. The retreat was comparatively orderly, but so swift that Italian cargo planes sent to supply the army found themselves inadvertently dropping bags of grain onto the pursuing Greeks. Given his almost pathological hatred of the Greeks, the army’s unilateral abandonment of Greek territory was a bitter pill for Mussolini to swallow. “I want the truth,” he thundered at General Cesare Ame, his head of military intelligence, “because I am going to have various heads blown off by a firing squad.”

“They Should Carry Mandolins Instead of Rifles”

No one was executed. Mussolini settled for sacking his defeatist chief of staff, Pietro Badoglio. His mood was not improved by a letter that Ciano hand-delivered to him from Adolf Hitler, whom Ciano had just met with in Berlin. In the letter, Hitler complained—fairly mildly, given his personality and the immense stakes involved—that the Italian invasion had had “displeasing psychological consequences” and “very grave military consequences” throughout the region. Mussolini was forced to agree. “This time he really has slapped my fingers,” Il Duce told his son-in-law.

While the Italian army settled into a new position 20 miles inside Albania, the onrushing Greeks were almost puzzled by the lack of resistance. General Papagos, fearing a trap, hesitated to order an all-out pursuit. Had he seen a copy of the confidential supply report forwarded to Mussolini’s new chief of staff, General Ugo Cavallero, Papagos might have been more assured. In it, Cavallero was informed that the army in Albania was virtually naked: “Reserve rations, nil. Equipment, minimal. Woolen clothing, zero. Infantry ammunition, none. Artillery ammunition, insignificant. Arms and artillery, all supplies exhausted. Engineering equipment, practically nil. Medical equipment, inadequate.” When the first Italian prisoners were led into Athens, Greek citizens did not know whether to laugh or cry. “I feel sorry for them,” an old woman said. “They are not warriors. They should carry mandolins instead of rifles.” At Menton, on the French-Italian border, a Gallic wag put up a sign that advised, “This is French territory; Greeks, don’t pursue the Italians past this point.”

With the worst winter in two decades settling over the Balkans, the Greeks had no intention of going any farther for the time being. All along the 156-mile front, both sides settled in for a miserable season of waiting and suffering. Like a macabre replay of World War I, the men shivered together in trenches carved out of ice and frozen mud. Cases of frostbite numbered in the thousands. Particularly dreaded was the so-called “dry gangrene,” also known as the “white death.” The affliction started painlessly, and men did not even know they had it until they looked down and saw their feet and legs swollen to twice their size and turning black. Amputation was the only treatment, and hundreds died anyway in the overcrowded field hospitals. In Rome it snowed on Christmas Day, moving Mussolini to observe callously: “This snow and cold are very good. In this way our good-for-nothing men and this mediocre race will be improved.”

Angry and embarrassed by the stalemate in Albania, Mussolini placed the blame on the soldiers themselves, complaining, “The human material I have to work with is useless, worthless.” At the end of the year, he sacked their dreamy commander, Soddu, and gave the post to Cavallero, a cultured intellectual who spoke both German and English and held a degree in mathematics. His enemies, unimpressed with his academic credentials, called him “the profiteer general,” owing to his frequent transfers from military posts to lucrative industrial positions within the government.

Addressing the Troops on the Albianian Front

There was little profit for Cavallero in his new position. Reinforcements poured in by boat across the Adriatic Sea, but there was no room left for them to maneuver, and the net effect was a further reduction in the army’s already scant rations. The Greeks fared somewhat better. Frontline units were transferred regularly to the rear, and Greek civilians in the region provided additional food and shelter. There was also a notable difference in the men’s morale. The Greek forces were jubilant; they continued localized attacks—described by Cavallero as “frenzied”—and on January 9, they captured the key crossroads village of Klisura, decimating the famous Lupi di Toscana (Wolves of Tuscany) Division in a driving snowstorm. After the defeat, cynics renamed them the Lepri di Toscana, or Hares of Tuscany.

Not even the death in January of Prime Minister John Metaxas, who succumbed unexpectedly after a botched operation on his throat, dimmed the Greeks’ esprit de corps. Conversely, the Italian soldiers at the front grumbled loudly about their empty stomachs, threadbare uniforms, and flapping boots; and back in Italy the number of new enlistments dropped significantly. Even more troubling to Mussolini personally was the stone-faced silence that greeted his appearances in movie newsreels and his radio broadcasts.

Determined to somehow break the stalemate and “put an end to this passivity,” Mussolini flew himself to the Albanian front in early March. Decked out in the beribboned uniform of First Marshal of the Empire, Il Duce toured the front, reviewed the troops, and made a brief visit to a field hospital. Leaning over the bed of one soldier whose stomach had been torn open by a Greek grenade, Mussolini beamed, “I am the Duce and I bring you the greetings of the fatherland.”

“Well, now, isn’t that great,” the soldier retorted. Other soldiers, as yet unwounded, cheered their leader and begged him to give them the order to attack. At least one of their number, a bearded veteran, ignored the stage-managed demonstration. A member of Mussolini’s staff watched as the soldier stood apart from the crowd, quietly eating his lunch. “While raising his spoon to his mouth he kept gazing at his excited fellow soldiers,” wrote Francesco Priccoli, “and every now and again his hand stopped over his mess tin as if he were dumbfounded by a scene that was obviously incomprehensible to him…. [He] went on eating for a moment, and then began slowly backing into the bushes and disappeared from my sight.”

Undeterred by his mixed reception, Mussolini climbed to the top of a 2,500-foot hillside at dawn on March 9, 1941, to watch the long-awaited offensive begin. Some 50,000 soldiers massed in the Desnizza Valley west of Klisura, while Italian artillery fired a ground-shaking 100,000 rounds at the Greek line in the space of two hours. Italian dive-bombers contributed to the bombardment. Unfortunately for the attackers, the Greeks had already captured an Italian officer with a complete set of plans for the operation in his possession. The Italians were sitting ducks—or moving targets.

A Final Fiasco for Mussolini and Hitler

For the next five days, the Italians made charge after charge against the Greek lines, only to be driven back easily by the entrenched enemy. Mussolini himself made several trips up and down the hillside to watch the attacks, carrying his marshal’s baton with him like a stage prop. Once, a Greek fighter plane strafed the observation post, and Il Duce was hustled into an air raid shelter. Aides reported to the public that he “behaved courageously.”

Finally, on March 16, Mussolini and Cavallero called off the attack. Twelve thousand Italian casualties—1,000 per division—had been added to the list of the fallen in a campaign that failed to regain a single foot of lost territory. Five days later, Mussolini left Albania, telling his aide Pricoli: “I am disgusted by this environment. We have not advanced one step. They have been deceiving me to this very day. I have a profound contempt for all these people.”

Even more disgusted than Mussolini was Adolf Hitler, who had been watching the Greco-Italian War with a jaundiced eye. As he had predicted at the outset, the entire misguided adventure had been a fiasco. Even worse, by encouraging the Greeks to open their airfields to British warplanes, the impasse in the Balkans now threatened to compromise Hitler’s cherished invasion of the Soviet Union. To prevent that from happening, the Führer reluctantly prepared to invade Greece himself with 600,000 battle-hardened troops. All he asked of Mussolini was that he “not undertake any further operations in Albania.” That, at least, was a promise Il Duce would be able to keep.

Originally Published July 1, 2015

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments