By Sam McGowan

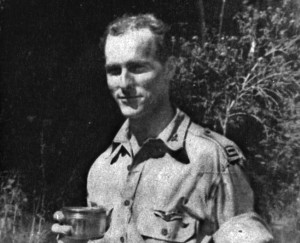

Lieutenant Colonel William Edwin Dyess, a U.S. Army Air Corps pilot and squadron commander, was considered a hero by men who served under him in the Philippines and who felt they owed their own lives to Ed’s sacrifice.

Born August 9, 1916, Ed Dyess was a Texan in the truest sense of the word. A member of a family with strong southern roots—his ancestors arrived in Georgia before the Revolution—he grew up in the small town of Albany, a plains town some 30 miles from the modern Air Force base that bears his name. His father was a local judge and tax assessor who had migrated to Shackleford County to take a position as a school teacher just before his son was born. Even though his father was an educator and politician, Ed’s family had a strong military tradition dating back to when Georgia was a colony and Dyess men fought in the Indian Wars.

Both of his grandfathers fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War, and one was captured and sent to a POW camp from which he escaped to fight again, thus setting a precedent his grandson would follow nearly a century later. His paternal grandfather was captured by Union troops while on a scouting mission in Pennsylvania and incarcerated in a notorious Union prisoner of war camp near Chicago. After refusing an offer of parole because it would prohibit him from rejoining his unit, Dyess’s grandfather managed to overpower a guard and escape, then made his way south through Illinois, Kentucky, and Tennessee to rejoin the Confederacy and fight until the end of the war. It was a remarkable escape and journey through two northern states and across Union-held territory—not to mention an exercise in determination that Ed inherited.

“West Point of the Air”

Ed’s interest in aviation was typical of many young men of his day. He and his father were inspired by Charles Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic along with the rest of America as the country became air-minded. His dad took him up for his first airplane ride when a barnstormer stopped for a few days in their community. Yet, even though he came from an air-minded family, aviation was not his first choice. The boy wanted to join a carnival, but as a teenager he started taking some bootleg flying lessons from another passing barnstormer, although not with the intention of becoming a professional pilot. His father’s position as a county judge and tax assessor led him toward a career in the legal profession, and after high school he attended Tarleton College in Stephenville, Texas, in preparation to study law at the University of Texas in Austin. He spent the summer before he was to begin studies at Texas working as a roustabout in the oil fields.

One of Ed’s coworkers had recently washed out of the U.S. Army aviation program at Randolph Field, Texas, and their conversations prompted Dyess to remember the flying lessons he had taken a few years before. He began having doubts about the legal profession and decided to go in the Army and become a pilot. He told his father he wanted to get an appointment to the Army’s “West Point of the Air.” Instead of expressing consternation, Judge Dyess was pleased with his son’s decision and told him, “Son, if it can be got, we’ll get it.” He got the appointment as an aviation cadet and reported to Kelly Field at San Antonio for flight training.

Military flight training was a dangerous proposition in the 1930s, and Dyess soon came to know death firsthand as some of his classmates “bought the farm” in training accidents. The daily exposure to danger made him develop a stoic attitude toward death and his own mortality. Having been raised in the Presbyterian faith, he had been schooled in the tradition of Calvinism, which teaches that man’s destiny is predetermined by the will of God. Upon graduation from pilot training and being commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Reserve, Dyess was assigned to the 20th Pursuit Group at Barksdale Field near Shreveport, Louisiana.

A Pilot in the Philippines

In November 1939, the 20th Pursuit was transferred to California and Lieutenant Dyess went with it. After his transfer to California, he met Marijean Stavik, a young woman from Champaign, Illinois, whose family published the Champaign newspaper. They were married in the fall of 1941, only a few days before Ed’s departure for the Philippines. America was gearing up for imminent war with Japan, and his transfer was part of a major buildup of the U.S. Army’s Philippines Department.

When the 35th Pursuit Group deployed two of its squadrons to a classified overseas destination, Dyess sailed for Manila in the fall of 1941 aboard the transport Winfield S. Scott. A first lieutenant, he had been elevated to commanding officer of the 21st Pursuit Squadron. They set sail from Hawaii on November 6, not knowing where they were bound until the ship was out of the harbor and at sea, at which time they were told that the code word “Plum” that had been stenciled on their baggage stood for the Philippine Islands, where they were to join the 24th Pursuit Group.

The news should not have been a surprise. War clouds had been gathering in the Pacific for several months, and the Army had begun a buildup of forces in the Philippines that included a number of pursuit squadrons. Although the 21st and its sister squadron, the 34th, had their full complement of ground personnel, each squadron was only at half strength in pilots. Additional pilots were expected to arrive on other ships, but as events unfolded over the next few weeks, the other ships never reached the islands and the latecomers ended up in Australia.

The two squadrons also sailed without airplanes. They were expecting to receive brand new Curtiss P-40Es when they arrived in Manila, but when they reached their new assignment at Nichols Field they found that their airplanes, which had been shipped separately, had yet to arrive. Instead, they were given Seversky P-35s that had recently been replaced by P-40s in the 24th Pursuit Group. The 21st operated the obsolete P-35s for a couple of weeks, but on December 5—only three days before the outbreak of war—the squadron was equipped with brand-new P-40Es that had just been assembled at the air depot at Manila.

The P-35s went to the 34th Pursuit Squadron, which relocated to Del Carmen, a newly constructed airfield north of Manila, while the 21st remained at Nichols. Nichols was also home to the 17th Pursuit Squadron, commanded by 1st Lt. Boyd “Buzz” Wagner. Wagner had been in the Philippines for a year, and Dyess turned to him to learn the ropes. Wagner’s squadron had been equipped with P-40Es in October, but the 21st’s airplanes were right out of the shipping crates. The mechanics and pilots worked feverishly to prepare their new airplanes for operational use, but they were up against a timeline they were not aware of.

Since the new airplanes were being delivered straight from the factory, most of the engines needed slow-timing (operations at reduced power for a specified time to allow the piston rings to seat), and some of the guns had yet to be bore-sighted. There was a shortage of oxygen tanks on Luzon, which restricted high-altitude operations to 15,000 feet. America was preparing for war in the Philippines but was lacking an important commodity—time. Equipment that was necessary to bring the pursuit squadrons up to full combat readiness was still at sea when war broke out—if it had even left the depots in California—and would be diverted to Australia.

Hasty Preparations For War

Although Dyess and his men had only been in the Philippines a few days, he was well aware of the severity of the situation. On Saturday, December 6, he made a bet with squadron mate Lieutenant Sam Grashio, who had commented that the United States would not go to war with Japan at all. Dyess asserted that the war would start within a week. Colonel Harold George, commander of V Interceptor Command, talked to the young pilots that day and advised them that when war came they would be fighting a holding action until reinforcements could come from Hawaii and the United States. He told them that they had about 70 first-line fighters available to defend against attack and that he thought they could put on a good performance.

The colonel made no bones about their situation as he advised his young pilots that while their mission was not exactly suicidal, it was not far from it. This was not comforting news, and the young men were sobered by the reality of their situation. None of them comprehended just how desperate their circumstances really were.

The 21st Pursuit Squadron received the last four of its 18 P-40Es that evening. All of the airplanes were brand new and had just been assembled out of the crates they had been shipped in from the factory. None of the engines had been slow-timed, and with less than four hours average flying time on them, none of the fighters had been properly broken in before they were thrown into combat. There was no oxygen available for high-altitude flight, and the radio sets were poor. No ground control network had been set up, and there was only one operational radar site in the islands. It would be destroyed by a Japanese air attack during the opening hours of the war.

Every man in the Philippines knew that war was on the horizon, but the United States had yet to adequately prepare for it. Although the attack on Pearl Harbor in faraway Hawaii came as a surprise, U.S. forces in the Philippines were feverishly preparing for war. A secret message had been sent from the White House to military commanders in the Pacific in mid-November advising them that war with Japan was imminent. The message also stressed that it was imperative that Japan be allowed to strike the first blow, an admonition that led to confusion at the higher command levels as to how to deal with Japanese aggression such as reconnaissance flights and whether or not to conduct reconnaissance of their own. The message was clear in one regard. It instructed commanders to bring their forces to alert status and to prepare for war.

The Air Corps, in particular, had been on full alert for several days, and at 0230 hours on December 8 the pilots of the 17th and 21st Pursuit Squadrons at Nichols Field were scrambled to their airplanes. The same thing had happened on the preceding six mornings. After about 10 minutes they were told to stand down, and most of the men returned to their quarters.

Two hours later, Dyess received the first news of the attack on Pearl Harbor when the phone in the squadron orderly room rang at about 0430. Word of the attack had reached the islands through a commercial radio station an hour and a half before, and Navy commanders had been notified shortly thereafter, but official notification did not come until later.

Only Eight Fighters Left

The headquarters of General Douglas MacArthur, commander of U.S. forces in the Philippines, received word of the attack at about 0400, but it was not until 0530 that the news was officially verified with a message from the War Department. By that time the men of the 21st Pursuit Squadron had returned to their operations building. They were immediately ordered to report to their airplanes and start engines. After about 10 minutes with no takeoff order forthcoming, Dyess instructed his pilots to cut their engines and stand by. The pilots climbed out of their cockpits but remained close to their airplanes. Boyd Wagner’s 17th Pursuit Squadron was ordered to take off, but the 21st waited—and continued waiting for the rest of the morning. Wagner’s squadron had an unfruitful mission patrolling just north of Clark Field.

At about 11:30, Dyess was ordered to take his squadron airborne and head north to cover Clark Field while the fighters based there were refueled after having landed from a fruitless mission to northern Luzon. A formation of Japanese bombers had been detected, but the P-40s failed to make an interception and returned to Clark to refuel. They had completed refueling and were lined up at the end of the runway preparing to take off when bombs began falling on Clark Field. A few P-40s got off the ground, but most of the squadron was caught by the falling bombs and their fighters were destroyed or severely damaged.

Shortly after takeoff, Dyess received instructions to patrol between Corregidor and the naval base at Cavite, some distance to the south of Clark. The second flight was late taking off and failed to get the message to divert to the south, so they set off for Clark by themselves. Almost immediately, two of the new Allison engines began throwing oil, forcing the pilots to turn around and head back to Nichols. The four other P-40s continued north toward Clark. They arrived overhead but saw no indication of enemy activity, so they turned west after some fighters they could see in the distance, probably P-40s from the 3rd Pursuit, which was based at Iba on the other side of the Zambaleses Mountains from Clark.

A few minutes later, the call went out for “all pursuit to Clark” and they turned around. A third engine started throwing oil, and the pilot turned south to return to Nichols. The three remaining pilots arrived over Clark in the middle of the attack, and one, Lieutenant McGown, disappeared after possibly witnessing a fellow pilot under attack by Japanese fighters while descending in his parachute and going to assist. The other two, Lieutenants Grashio and Williams, managed to shoot down one Zero, then came under attack themselves. They managed to evade the Japanese fighters and make their way back to Nichols, where they found Dyess waiting for his men with cold Coca-Cola and sandwiches from the squadron mess.

The squadron spent the rest of the day on fruitless patrols. As evening approached, Dyess was told to move to Clark since Nichols Field was expected to be the next target for a Japanese attack. The main runway at Clark had been cratered by bombs, and the fighters were forced to use the dirt auxiliary strip. It was the dry season, and the runway was covered with dust, which rose in a cloud after each landing. Darkness was falling, and the combination of reduced visibility and dwindling light prolonged the time necessary to get all of the fighters on the ground.

Engine failure had reduced the squadron’s strength from 18 to 11 fighters. Its strength was further reduced early the next morning when one pilot hit a B-17 bomber while attempting to take off and another crash-landed when the pilot became disoriented after taking off into the cloud of dust that had been stirred up by the propellers on the dirt runway. A third P-40 lost an engine at 7,000 feet and had to glide back into Clark, only to be fired on by friendly antiaircraft guns. Dyess now had only eight serviceable fighters left, but his mechanics at Nichols were working feverishly to repair the ones that had aborted the previous day.

Day Three of the War

December 10, the third day of war, was the worst day for the Interceptor Command, although the culprit was not the superior numbers and skill of the Japanese fighter pilots but rather another stroke of the bad luck due to poor timing that plagued the Air Corps in the Philippines. Late that morning, Dyess encountered enemy aircraft for the first time and saw his fire rake one from nose to tail. But he was concerned about two others that were in the area and did not see what happened to his quarry.

Later that afternoon, Dyess was eating lunch with Wagner when they were notified that enemy bombers were approaching Clark Field. They made their way to the strip and took off separately into a cloud of dust. They were both shocked when they emerged from the dust cloud and discovered that only inches separated their wing tips! The bombers had turned toward Manila, so Dyess and the other pilots were ordered to head in that direction. When he saw the bombers in the distance, he pressed his gun button to warm up his guns, but nothing happened. After several attempts he landed at a nearby auxiliary field, where he managed to charge his guns with a screwdriver and help from some soldiers. It was a common problem.

outclassed by Japan’s faster, more maneuverable Mitsubishi “Zero” fighter, but the American pilots made up for the P-40s shortcomings by being brave in the attack.

By the time Dyess took off, the enemy formation had vanished and he missed out on the one major air battle of the Philippines. On December 8, the Interceptor Command counted approximately 70 operational fighters. The action on December 10 severely depleted the 50 or so that were left after the engine failures and combat losses on the opening day of the war. Only a handful were shot down, and the fighters accounted for a large number of Japanese aircraft, but by the time the fighters engaged, many of them had been aloft for some time and were running low on fuel.

Three P-40 pilots were killed and at least eight bailed out; most of the rest were forced to crash land wherever they could as their engines coughed their last due to fuel exhaustion. By the end of the 10th, total American fighter strength was down to 30 airplanes, of which only 22 were P-40s. The other eight were P-35s, which were all nearly worn out. Four P-40s were being assembled at the air depot and were completed as Manila was being abandoned on Christmas Day.

The Field at Lubao

With fighter strength severely depleted, MacArthur’s headquarters decided it was foolhardy to continue risking the precious planes against overwhelming odds, but rather to conserve them for reconnaissance and attacks on ground targets. Dyess was ordered to take the remnants of his squadron back to Nichols Field, where the pilots were reunited with their ground crews for a short time. With their aircraft depleted, the need for pilots had decreased, so some of Dyess’s men were transferred to the Signal Corps to serve as aircraft observers. The rest of the squadron was ordered to move to a new airfield that was still under construction at Lubao, a town on the edge of Manila Bay.

The Lubao strip had been cut out of a sugar cane field, and the Filipino and American troops used the cane as camouflage. Japanese bombers frequently flew over the field but never managed to spot the well-concealed P-40s. The remaining 26 P-40s and a single North American A-27 flew in late on Christmas Eve. The men were quartered some distance away, and the crew chiefs refused to leave their airplanes, staying on the airstrip to perform badly needed maintenance.

Dyess and his men had a sumptuous meal on Christmas Day as they feasted on turkey and trimmings that had been trucked from Manila, which was being evacuated. It was a meal they would look back on in their dreams and discussions as supplies on Bataan dwindled and after they became prisoners of the Japanese. As the last trucks rolled out, MacArthur declared Manila an open city, a political declaration designed to dissuade the Japanese from launching a military attack that could cause heavy casualties among the civilian population.

The day after Christmas, Dyess again engaged in aerial combat and shot down a Japanese dive-bomber, the first he was able to actually confirm, although none of his aerial victories were ever formerly credited to his record. Two days later, he was nearly shot down himself by an aggressive Japanese Zero pilot who caught him unawares. After his airplane was struck by a burst of fire, Dyess began a dive to build up speed, then pulled up into a zoom and came out of it ahead and above the enemy fighter. The Japanese pilot turned toward him, and they rushed head-on until the heavier .50-caliber fire from the P-40 blew the top off the Zero’s engine and set it on fire.

Dyess later reported that several of his pilots got their first Japanese aircraft during this period. On December 30, Dyess and his wingman had a field day when they spotted a convoy of Japanese trucks. The Japanese vehicles were American-made and difficult to distinguish from U.S. military vehicles, but one had the large red meatball on its hood that identified it as the enemy. The P-40s made two strafing passes on the seven trucks and left three burning and the other four shot to pieces. Pursuit pilots such as Dyess, Wagner, Lieutenant Russell Church, and Captain Grant Mahoney wreaked a heavy toll in Japanese lives and equipment, illustrating how effective the Interceptor Command could have been with reinforcement and resupply that never came.

On New Year’s Day, Dyess and his ground party completed work on the new field at Lubao. They had no more than finished when they got word that advancing Japanese troops were threatening the field. MacArthur had ordered a general retreat onto the Bataan Peninsula, and the Air Corps was to move with the troops. The combination of combat losses, accidents, and dwindling spare parts had reduced fighter strength to only 18 P-40s, which were divided between the 17th and 34th Pursuit Squadrons and initially sent to two airfields on Bataan, one at Pilar and the other at Orani. Half the P-40s were later ordered to Mindanao, an island in the Southern Philippines that was still in American hands and serving as a delivery point for transports bringing in supplies from Australia.

Personnel and aircraft from other units were rolled into the two squadrons, and a contingent of pilots, including Wagner and Mahoney, were sent to Australia to pick up some P-40s that had been on a ship at sea when war broke out and had been diverted to Brisbane. They would not return. The 21st Pursuit Squadron gave up its airplanes and was reorganized as a ground battalion. The new battalion was initially assigned as the base defense force at Lubao, while the air units moved to Bataan.

Airmen as Infantry

During the next three months, Dyess gained a reputation as one of the most effective officers on Luzon. He and his men scrounged up an assortment of weapons including .30- and .50-caliber machine guns that they took from wrecked fighters to supplement their rifles and submachine guns. The airmen modified the salvaged machine guns with homemade mounts so they could be used as infantry weapons. They also had a few Browning Automatic Rifles and four Bren Gun carriers, along with an assortment of submachine guns, modified Lewis guns, and hand grenades. When the battalion/squadron first moved to Bataan, they had an abundance of rations and supplies, but about two weeks after the move the quartermaster ordered that all surplus supplies be turned in. After that the men subsisted on what they were issued, supplemented by what they could find or kill, including horses and mules that had served as cavalry mounts and beasts of burden.

On January 17, Dyess was notified that a Japanese landing party had come ashore at Agoloma Bay. He and his men were loaded into trucks and driven seven miles to engage the enemy force. Initial estimates were that the landing party was small, about 30 men, but it turned out to be at least 20 times that size and the resulting battle lasted for several weeks.

The airmen joined some Filipino constabulary forces and a few engineers from the 803rd Engineering Battalion to meet the attacking Japanese troops. The Japanese overestimated their opposition and retreated. As they were pushed back toward the cliffs overlooking the bay, they began digging in, turning the engagement into a siege. Dyess and his men remained in opposition to the Japanese for a week, then were temporarily withdrawn for a six-day rest and replaced by Philippines Scouts. During the week they had been there, the airmen-turned-infantry managed to push the Japanese back toward the cliffs some 150 yards. During their respite from combat, the airmen were engaged primarily in fighting forest fires. When they returned, they found that the Filipinos had gained about 50 yards, but at tremendous cost. The Scouts had suffered nearly 50 percent casualties.

The Air Corps troops reinforced the Philippines Scouts and pushed the Japanese farther back until they were only about 400 yards from the cliffs by the bay. By the fifth day, the line was down to about 300 yards, and four American tanks arrived to provide support. Suddenly, the Japanese began ripping off their uniforms and leaping over the 50-foot cliffs onto the sandy beach. Some went over the side to descend to prepared positions, but large numbers simply jumped to the beach in an attempt to escape. As the Americans advanced, they could see their enemy on the sand below. They were running up and down wildly, some were into the surf in an attempt to swim away. The American airmen and Filipino soldiers raked them with automatic weapons fire, killing everything that moved. The Japanese that had taken shelter on the side of the cliff continued to hold out and were practically impervious to the dynamite, grenades, and mines that were lowered on ropes and exploded next to the cliff face.

On the eighth day after Dyess’s men returned to the battle, they finally wiped out the Japanese force with assistance from the Navy, which supplied two armed Boston Whalers and two armed longboats. Some of the airmen went out in the whalers while Dyess, who had been promoted to captain and then to major, was in one of the longboats to direct fire. The sailors raked the cliffside with machine guns and captured 37mm cannon.

The attack continued even as a flight of Japanese dive-bombers knocked out all four boats, but not before they had destroyed the Japanese defenders. The Army personnel stormed the beach and finished off the survivors. Only one Japanese soldier was taken prisoner. Dyess and his men counted over 600 bodies after resistance ceased; countless others had been swept out to sea. After the battle, Colonel George visited the men of the 21st Pursuit Squadron. He told them they were returning to aviation duty, and Dyess presented the colonel with a captured Japanese sword.

Modifying the P-40s

Dyess’s new assignment was as field commander for the Bataan and Cabcaben airfields. A third airfield was under construction at Marivelles under the supervision of Captain Joe Moore, who had managed to get in the air during the attack on Clark Field. U.S. air strength on Bataan had risen to 10 airplanes, but only five were first-line P-40s, and those consisted of two different models. The other five included a Bellanca, a Beechcraft, an Army O-1, and a couple of other ramshackle light transports that made up what the men had begun to call The Bamboo Fleet. It was under the loose command of Major William “Jitter Bill” Bradford, a former civilian air taxi pilot who had joined the Army before the war as an engineering officer. Colonel George had limited the fighters to reconnaissance and resupply missions while holding them in reserve to be used to meet large-scale ground attacks.

The ground crews worked on the fighters to improve their combat capabilities, including developing a bomb release mechanism that allowed the P-40s to carry 300- and 500-pound bombs. The main problem for the airmen on Bataan was a lack of food. Although large supply dumps remained, there was practically no meat or other sources of vital protein. By the end of February, all the horses and mules had been slaughtered for food. Bradford volunteered to fly to Cebu and bring back supplies. After he made two successful round trips, other pilots went to pick up food. Dyess made at least one trip himself. But the cargo capacity of the small transports was limited, and it was hardly enough to supply the men on Bataan.

In early March, Dyess’s P-40 had been modified to carry bombs, and almost immediately lookouts reported the presence of a large number of ships in Subic Bay. Dyess asked for permission to mount an attack, but Colonel George was reluctant to authorize the mission. However, the next day, March 3, Dyess got word to come to the airfield, where his airplane was being loaded with a 500-pound bomb. Colonel George advised that Japanese ships were unloading supplies at Olongapo, and he thought they should be discouraged. Another P-40 had already gone out with a load of fragmentation bombs and came back to report that he had dropped them but was unable to assess the damage. Dyess took a wingman and headed for Subic Bay, where he found the largest concentration of ships near Grand Island in the bay rather than at Olongapo. Dyess identified his wingman only as “Shorty” in his account after his return from the Philippines because he was still a prisoner of the Japanese.

Three Attacks in Subic Bay

Dyess made three attacks on the Japanese ships in Subic Bay and the supply dump on Grand Isle before the day was out. On each occasion, he went out with a 500-pound bomb which he delivered by diving from about 10,000 feet. The bomb he dropped on his first attack missed the ship he was aiming at, but after the drop he went low and strafed it three times. After his third pass, he saw the ship stop dead in the water. He expended his ammunition on four warehouses and one of two vessels he estimated at 100 tons.

Dyess was joined in the attack by other pilots from his squadron and from Joe Moore’s squadron at Marivales. After refueling and rearming, he returned for a second attack, and even though his bomb again missed a transport, it exploded among several smaller vessels, which were tossed into the air by the geyser of water. He then went in for another strafing attack on the warehouses and vessels in the harbor. One of his targets was the second of the two 100-ton vessels he had spotted on his first strike. Dyess raked it from stem to stern with his guns and then watched it sink.

Colonel George did not want to let Dyess go back for a third sortie but finally relented. Lieutenant John Burns went along as his wingman. It was near dusk when they approached the target, but there was still plenty of light for the attack. Two large freighters had been tied up at the dock during the previous attack, but they had both shoved off and were maneuvering in the bay, so Dyess chose the supply complex on Grand Island as his target. He dropped his bomb at 1,800 feet and saw it score a direct hit that set off a series of secondary explosions, starting a fire that burned into the next day. Large, softball-sized tracers were coming up at him from the fleet of cruisers and destroyers that filled the bay.

Observers situated on Marivales Mountain reported that a large transport was slipping out of the bay, so Dyess elected to bypass the ships in the harbor and the tracer-filled sky and flew toward the transport until he could see it silhouetted against the sunset to the west. He made two passes and saw fires breaking out all over the ship. He was at 1,800 feet in a 45-degree dive for another pass when the ship blew up. It was getting dark, but the light of the fire and the remnants of the sunset allowed him to spot another large ship that was throwing up a tremendous amount of antiaircraft fire. After his second pass, fires were burning all over the deck. He concentrated his fire on the bridge on the third pass and ran out of ammunition. The ship had been severely damaged and ran aground on the beach, where it burned for two days.

Dyess was not alone in the attacks on the ships and supply dump, but his attacks were the most successful. One pilot and airplane were lost early in the day. Darkness claimed three of the remaining four. Dyess’s wingman, Lieutenant Burns, ground-looped during landing, and his guns went off and sprayed tracers around the airfield. Two pilots who had taken off from Marivales landed with a tailwind and cracked up both airplanes, leaving Dyess’s single fighter as the operational P-40 force on Bataan.

“Rid the Skies of Japanese Fighters”

During the next few weeks the ground crews managed to assemble another P-40 out of the three wrecks. Since it was made from parts from different models, the pursuit airmen referred to it as the “P-40 Something.” The attacks had been costly for the Americans, but in terms of actual damage they were far more costly to the Japanese. Tokyo Radio reported that Subic had fallen under attack by three flights of four-engine bombers with fighter escorts. Dyess would later comment that the problem was that the Japanese could easily replace their losses, but the Americans could not.

Dyess was awarded two Distinguished Service Crosses for his actions in the Philippines. His performance was an example of the dedication of an amazing group of young men who continued to press the fight against the Japanese against overwhelming odds. Ed Dyess, who had come to the islands as a first lieutenant and had been promoted to major, was an individual identified as crucial for the war effort when it became apparent that Bataan was going to fall. He was ordered to fly his P-40, which he had named “Kibosh,” off of the island to Mindanao, where he would be evacuated to Australia.

In mid-March, Colonel George met Dyess at Bataan Airfield and told him that he had been ordered out of the Philippines with MacArthur, who was going to Australia to become Supreme Commander of Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific. George, who was promoted to brigadier general but would die in an aircraft accident a few weeks later, told Dyess to tell his men that if he was not back shortly, it was not because he did not want to return. Dyess was essentially in command of the last of the interceptors left on Bataan: a pair of P-40s and a couple of P-35s.

By early April, the situation on Bataan had become desperate. There was a severe shortage of food and medical supplies. Dyess was advised that on April 10 some ships (actually submarines) were going to arrive from Cebu with supplies and that bombers would be attacking Japanese positions to provide cover for the deliveries. He was to take his remaining fighters and “rid the skies of Japanese fighters.” Dyess and the other men on Bataan had no way of knowing that a mission was being mounted from Australia; they were only told that there would be air attacks. As it turned out, the air raids did not take place until April 13 and, with the exception of a single mission against Nichols Field, were directed against Cebu itself, which had fallen into Japanese hands the day before. By that time Dyess and his men were prisoners of war.

Taken Prisoner on Bataan

On April 9, Maj. Gen. Edward P. King, the senior American officer on Bataan, surrendered his command. As Japanese forces approached Bataan Airfield, Dyess was ordered to take his P-40 and fly out, but he felt he could not abandon his squadron and got permission to stay. He gave the airplane to Lieutenant Jack Donaldson, telling him to go out and bomb and strafe the approaching enemy, then to come back over the base and if the Japanese were as close as they had been told, to rock his wings and head south for Cebu. Donaldson was back in 15 minutes with his bomb racks empty. He rocked his wings, then turned south to Cebu, where he was forced to land wheels-up as the airplane’s hydraulics had been shot out.

Dyess picked men whose names had been given to him by Interceptor Command headquarters and sent them out in the remaining planes. One of those evacuated was Captain Ben Brown, one of three men who flew out in a P-35. A few months later, Brown talked to New York Times reporter Byron Darnton, telling him of the heroism and dedication of his commanding officer, Major William E. Dyess, and how he had given his own airplane to one of his pilots to fly out of Bataan. The dispatch was printed in newspapers around the country, then buried in archives and forgotten until the following year.

After he got word that General King was going to surrender, Dyess considered his situation. He originally hoped to find transportation for his pilots to Corregidor, but when he learned that no boats were available he debated whether to surrender his men or take them into the mountains and join the guerrillas. He knew the locations of the guerrilla camps, but they were some distance away. The Navy gave his men food, but they had no quinine and he hesitated to take them into the mountains without it since the woods were infested with malaria-carrying mosquitoes.

Dyess and his men had decided to try and join the guerrillas, but after they had gone about two miles they encountered three Japanese tanks. An officer stood in the open turret of one, pointing an automatic pistol in their direction. The enemy officer gestured for the Americans to move off the road into a depression. Dyess and his pilots decided to eat, then get some sleep and plan their next move after they had rested. They never got the chance to make a next move, as they were awakened by Japanese soldiers and taken prisoner.

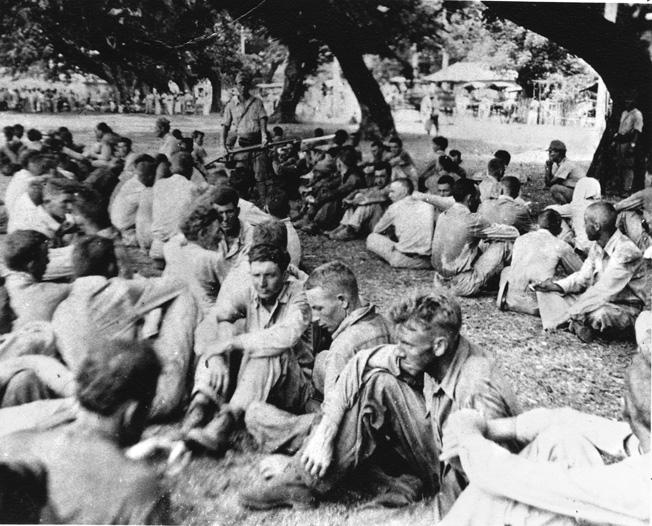

The Bataan Death March

Dyess and his men found themselves in the worst of the infamous trek from Bataan to San Fernando that will forever be known as the Death March. A few days before the surrender, Dyess had obtained extra food for his pilots so they would be able to continue flying, and they were in a little better shape than most of the other soldiers, but they entered an ordeal that was far beyond their ability to foresee—and which was nearly impossible to endure.

General King and his staff expected their men to be given humane treatment after the surrender, but the victors considered the prisoners to be no more than vermin. To the Japanese, surrender was a forfeiture of honor and respect, and they considered the Americans and Filipinos as objects of disdain. The deadly march had not even begun when Japanese soldiers demonstrated their brutality and low regard for human life. The victorious Japanese searched the prisoners time and time again, looking for anything of Japanese origin.

One Air Corps captain was being searched by a Japanese private, who reached into a pocket and pulled out some yen. The private immediately forced the burly captain to his knees as he pulled out his sword. He raised without ceremony and brought it down on the back of the man’s neck, severing the head from the body. Dyess knew the captain but was too far away to actually see the beheading. The man had been in charge of an observation post well behind the lines, and Dyess doubted if he had ever seen a dead Japanese soldier. The unfortunate captain was the first of thousands of American and Filipino soldiers who would die at the hands of their captors or from illness and starvation over the next few weeks.

During the 85-mile trek to the railhead where they were finally loaded on crowded cars for the final leg of their journey to Camp O’Donnell, the men received little food or water and were subjected to the harshest treatment imaginable. Suffering from starvation and sickness, many of the prisoners were unable to maintain the pace the guards expected. Other prisoners tried to carry them as best they could, but men dropped by the hundreds. They were taken care of by clean-up squads of Japanese soldiers who shot or bayoneted the unfortunate men where they lay, then left the bodies for other prisoners to stumble over as they came up the terrible road of death.

Dyess and the remnants of his squadron were on the march for five hellish days. The sadistic Japanese soldiers tormented the men with captured rations and made them stand or sit in the hot sun for hours. Thirsty men who broke ranks and attempted to reach streams and wells were shot. The exact death toll from the march will never be known. Approximately 75,000 men surrendered on Bataan, of which 11,000 were Americans. As many as 21,000 died on the road between Marivelles, where the march began, and their arrival at Camp O’Donnell. Even more died in the disease-ridden camp.

A POW at Camp O’Donnell

Dyess remained at Camp O’Donnell for two months. At first only the men from Bataan were kept there, but after the surrender of Corregidor more troops joined the “battling bastards of Bataan” in the already overcrowded camp. Conditions were dismal. Dyess was part of a party that was sent to Clark Field to clean up wreckage. While on the Clark detail, he had an encounter with a Japanese soldier who spoke some English, and with Dyess’s smattering of Japanese they were able to have a conversation. The Japanese, who claimed to have fought in China and Singapore and on Bataan, held the fighting ability of the Americans in low regard. When Dyess asked him what the Japanese intended to do with their prisoners, the enemy soldier laughed, then drew his sword and made a couple of decapitating motions with it.

The soldier asked about the value of various items the Japanese had taken from their prisoners. Dyess noticed that the man was wearing a watch that looked familiar. He looked closer and realized it was his own, a military watch with a 24-hour dial that he had bought while on a flight to Cebu. He was tempted to ask how the man had gotten it but knew that would be a mistake. The soldier bragged about all of the victories racked up by his countrymen, but when he claimed that Japanese submarines had shelled Chicago, Dyess knew he was exaggerating. Dyess would have a similar conversation with a Japanese fighter pilot a few months later after he was transferred to Cabanatuan. The Japanese airman was more respectful of a fellow airman and seemed to be most concerned about the death of his squadron commander, who had been shot down by a P-40 pilot. As he took his leave, the Japanese pilot told Dyess he would be seeing him again. An hour or so later two Japanese fighters flew low over the camp.

When he returned to Camp O’Donnell from Clark Field, Dyess heard rumors that they were being moved to a new camp at Cabanatuan. At first they were encouraged by the news, but then it occurred to them that a few weeks earlier all of the senior officers had been sent to Japan and Formosa, where they were working as laborers. They were fearful that their chances of escape or exchange would be nil. The men also feared it might be a rumor. They soon learned that it was not; the Japanese had decided to separate the American and Filipino POWs, and all Americans would be moved to Cabanatuan while the Filipinos would remain at Camp O’Donnell. They were also told that they would be moved by truck, an announcement that no one believed.

The Japanese were true to their word, although the prisoners at first thought they were being tricked again when no trucks showed up at the place where they were supposed to load. Dyess was expecting another death march with the loss of hundreds of men, but the trucks finally arrived. The Americans noticed that most of them were of Chevrolet, Ford, and GMC manufacture. Japanese soldiers packed them into the trucks like sardines—so tightly that there was no room to move.

The Cost of Escape

Dyess spent several months at Cabanataun, where he found that while conditions were better than they had been at O’Donnell, they were still dismal. Prisoners were shot and some were tortured to death for various infractions. Three officers who decided to escape even if they died in the attempt were captured and brought back to the camp, where the Japanese made a spectacle of them. The three men were stripped naked and tied to posts with cross-pieces crucifixion-style and flogged repeatedly with pieces of timber. The torture continued through the day and into the night and then through the next day, until the Japanese officers realized that the men were beyond the point of feeling pain. They took the tortured bodies from their crosses and transported them from the camp. A few minutes later shots rang out.

Dyess was chosen to be part of a group of prisoners who were sent to Mindanao, where they would serve on work details in the vicinity of Davao. On October 24, 1942, they were loaded onto a railroad car and taken to Manila. The following day the prisoners were paraded through the city and marched to the docks, where they were loaded onto a decrepit British-made ship. It was a freighter, the holds filled with cargo, and it reeked with noxious odors. The men were not sure where they were headed until they saw the dark shape of Corregidor pass on their right and knew they were headed south, which meant they were going to Mindanao. Japan, Korea, and Formosa were all north of the Philippines.

Two companies of Philippine Constabularies were also on the ship. The Constabularies were government police, and the POWs were not sure what to make of them or where their loyalties lay. Dyess and some of the men worked up an escape plan but decided against trying to make a break for freedom. They learned too late that if they had gone ahead with their plan to take over the ship, the Filipinos would have sided with them against the Japanese sailors and guards.

The new camp at Davao was actually a civilian prison, and the other prisoners were Filipinos who had been convicted of crimes before the war rather than military prisoners. The Japanese had told the Filipinos that once they had taught the Americans to do their work, they would receive pardons, but when the Americans arrived, they were too emaciated to be very effective as laborers. Surprisingly, the Japanese increased their rations and included meat and vegetables to increase their strength.

At first the new prisoners thought their conditions had truly improved, but then the Japanese commander cut their rations to barely enough to keep them able to work. Very little medical care was provided, and the guards were not above the same brutality and murder that had been prevalent at the previous camps. Each day groups of prisoners were sent out to various destinations on work details in the rice and vegetable fields. Dyess was assigned to drive a cart to deliver materials to the various work details, a job that allowed him some degree of freedom and a means of possible escape.

The Filipino convicts helped the Americans learn how to look busy while doing very little work. The Americans also learned that their Japanese captors lived in fear of the Moro tribesmen who populated the southern islands. One of the prisoners was a Moro, and after he was tied up and flogged he was determined to get even. A few days later when the guard gave the prisoners a rest break, the Filipino picked up an ax in a motion so swift no one saw what happened and buried it in the guard’s neck. He then grabbed a bolo knife and carved up the Japanese guard’s body, then disappeared into the jungle with the man’s shoes and rifle. Fortunately, the Japanese did not seek retribution from the Americans since the culprit was a Filipino civilian convict and not a prisoner of war.

Dyess’s Escape

In February 1943, Dyess and Marine Captain Austin C. Shofner began plotting an escape. They discussed who else to bring into their plans. Dyess decided on Captain Sam Grashio from his squadron and an enlisted man named Leo. Shofner suggested two other Marine officers, Majors Jack Hawkins and Michael Dobervitch. They also included Navy Lt. Cmdr. Melvyn H. McCoy, who was an experienced navigator and ran a coffee-picking detail that allowed him to venture outside the camp. U.S. Army Major Stephen M. Mellnick and two Army enlisted men working with McCoy on the coffee-picking detail would also have to be included.

The group spent almost three months planning and accumulating equipment for their escape. Dyess’s job was to drive a cart pulled by bulls to deliver poles and other materials to the various work details outside the camp, so they concealed their supplies under the poles in his cart and he drove them to where they could be hidden on the edge of the jungle. On Sunday, April 4, almost a year since General King had surrendered his command on Bataan, they made their escape and plunged into the dense jungle. They made contact with local guerrillas, who at first were wary of them. Once they were convinced, the guerrillas became friendly and eager to help the men find their way across the island to a larger force.

Led by Filipinos, the escaped POWs spent two weeks walking through the dense jungle and swamps before they finally emerged on solid ground and made contact with American guerrillas. The guerrilla commander warned them against trying to make their way to Australia by boat and wanted them to join his command. The former POWs argued that they were all specialists and their skills would be better utilized if they returned to the American forces. Melnik and McCoy journeyed to the camp of Colonel Wendell Fertig, who they considered to be little more than a civilian in a uniform. Fertig was unfriendly and reportedly put the two officers under house arrest. Dyess, who had remained behind, grew impatient and set out to join his two fellow escapees.

By this time word of their escape had been sent to Australia, and in mid-June they learned that a submarine would pick them up at Sibuguey Bay, which was on the other side of the island. There was not enough time to get the rest of the group to the pickup point, and there was limited space on the submarine, so the three made their way to the bay and were picked up on July 15, 1943. As it turned out, a large Japanese naval force arrived in the same bay within days.

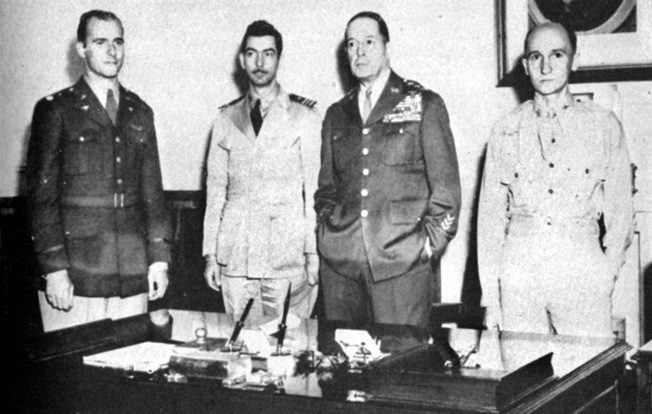

The newly freed men were taken to Australia where they reported to MacArthur, who presented the three with the Distinguished Service Cross, Dyess’s second, and told them to take their story to the United States. Dyess and the other two officers were sent to Washington, D.C., where they briefed military and civilian leaders at the highest levels. Dyess was saddened to learn that his friend Boyd Wagner had died in an aircraft accident the previous November.

“The Dyess Story”

At first their story was classified top secret out of fear that it would cause civilian morale to suffer. Finally, permission was given for Dyess to tell his story to the media, but then it was withdrawn again. The media were initially somewhat lukewarm to the story—other prisoners and internees had returned from Japanese captivity, although none of them had been on the Death March. Then someone discovered that Dyess was the same Air Corps officer whose exploits on Bataan had been reported in the Darlton dispatch a year before, and the newspapermen realized they had a real story to report.

Dyess’s wife, Marijean, was in the newspaper business and felt that since the Chicago Tribune had a large circulation it would be the ideal vehicle to get the widest distribution. Ed’s goal was to tell the world about the inhumanity of the Japanese soldiers responsible for guarding the American and Filipino POWs. Marijean used her contacts in the newspaper business to convince the Tribune, and a contract was signed. A Tribune journalist conducted a series of interviews with the young officer at the Greenbrier Resort at White Sulpher Springs, West Virginia, where he had been sent to recuperate.

After Dyess told his story, the War Department again put a clamp on it and refused to allow it to be published. Meanwhile, Dyess returned to duty and was sent to the Lockheed aircraft factory at Burbank, California, to become familiar with the company’s deadly P-38 Lightning fighter in preparation for a new assignment as a squadron commander in the Southwest Pacific.

Dyess’s heroic life came to an end on December 23, 1943, when the P-38 he was flying caught fire over the crowded residential areas along the Southern California coast near Burbank. Rather than risking loss of life on the ground, Dyess elected to risk his own life and attempt a crash-landing in a vacant lot instead of taking to his parachute. He died in the ensuing crash.

A few days after his funeral, Dyess’s family was told that he had been recommended for the Medal of Honor. There is some confusion as to whether the recommendation was for his exploits in the Philippines. Some believe it was for the attempted crash-landing, but since the Medal of Honor is a combat decoration, this is unlikely. None of the Air Corps airmen who fought in the Philippines were awarded the Medal of Honor, although several, including Dyess’s friend, Joe Moore, were recommended. Dyess was posthumously awarded the Soldiers Medal for choosing to sacrifice his own life in the burning P-38.

A few weeks after Ed’s death, the War Department gave permission for the Chicago Tribune to print “The Dyess Story,” which ran in a series of articles starting on January 28, 1944. The series was published in book form in the spring and instantly became a bestseller. Americans were shocked, dismayed, and incensed as they read the account and learned of the brutality of the Japanese soldiers and their officers.

Dyess himself became one more war hero whose life was cut short and soon faded away as news from Europe, where Allied troops had invaded Normandy, drew the nation’s attention. He was not forgotten by the men who had served under him in the Philippines or by his family and friends in Albany. In the 1950s, local citizens began a campaign to have Abilene Air Force Base renamed in his honor, and their request was accepted. Dyess Air Force Base is now the home to an Air Combat Command B-1 bomber wing and a wing of Air Mobility Command C-130 transports.

I am very proud to say that Ed Dyess was a relative —My great grandmother was named Violater Beasley Dyess(Rhodes)—-It gave me goose bumps to read of his experience and bravery —We can never honor a hero like this enough—His honor and his sacrifice will live forever!! Max Shumack

Max,

I am writing a World War II book that highlights 24 individuals that were in the Philippines at the start of the war. You relative, William E Dyess, is one of those that I am including in the book. I consider the 24 as ambassadors for the thousands of others whose stories I cannot tell. Where possible, I include the signature of the individual. Would you have his signature? Would you have any interests in reading his chapter to ensure its accuracy. Thank you for your time.

Tim Deal

CDR, US Coast Guard (ret.)

Ed’s sister Nell was living just south of me in Lake Jackson a few years ago. She was in her 90s and is probably gone now. I regret that I never got together with her. John Lukacs, who wrote a great book about the men who escaped on Mindinao, went by and visited her then met with me the following day.

Be advised that I did not write the picture captions. The comment that the pilots in the Philippines were “outclassed” by the Zeros is a myth. The facts are that the P-40 pilots did significant damage to the Japanese air forces. As Dyess said, the problem was that the Japanese could replace their losses but they couldn’t.

Japanese atrocities such as the ones depicted in this story fully justified Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

These atrocities were a direct result of the Bushido philosophy. During the Russo-Japanese War and WWI, the Japanese treated their Russian and German POWs very well indeed, especially the POWs held in Japan. Am sure today’s Japanese military would treat any POWs well.