by Marc G. De Santis

The third century BC saw fierce naval competition arise all across the Mediterranean. In the west, the Romans and Carthaginians struggled for control of the sea. In the eastern Mediterranean, the Hellenistic Successor kingdoms of Alexander the Great’s world empire engaged in a costly naval race, each trying to outdo the other by building the biggest ships.

Both the Romans and the Carthaginians had settled upon the quinquereme, or “five,” as their standard warship. It presented, for its day, a good combination of speed, power, and maneuverability in battle. Among the Hellenistic states, however, new and sometimes extraordinary types of warships appeared.

[text_ad]

The Quinquereme, Trireme & Hexere

The trireme, or trieres, in Greek, had long since been superseded in the Greek world by the tetreres (four) and the penteres (five). Alexander had larger vessels, such as the hexeres, or “six,” built just before he died for his planned invasion of Arabia. Even Alexander’s fleet, however, represented only a conservative increase in overall ship size in comparison to the monster galleys constructed by several of his Successors.

The trireme, or trieres, in Greek, had long since been superseded in the Greek world by the tetreres (four) and the penteres (five). Alexander had larger vessels, such as the hexeres, or “six,” built just before he died for his planned invasion of Arabia. Even Alexander’s fleet, however, represented only a conservative increase in overall ship size in comparison to the monster galleys constructed by several of his Successors.

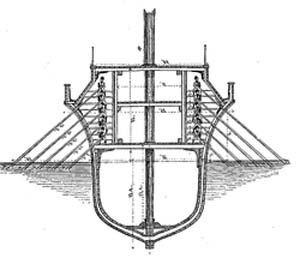

Various Successor kings constructed sevens, eights, nines, tens, elevens, twelves, fifteens, sixteens, and even thirties and at least one forty. Working out the oaring systems of the better-attested types of war galley in the ancient world is a difficult task. Doing so for these much larger vessels is nearly impossible. For the sixes and sevens, and probably the eights and nines, it is likely that extra rowers were added at one or more of the three levels of oars. As more rowers were added, the ships would have had to become a little wider in the beam to accommodate the extra crew. The much larger galleys would have required even more rowers and likely much greater expenditure to construct.

Larger and Larger War Galleys

What could explain the enthusiasm for ever-larger war galleys on the part of the Successors, as opposed to the more sober Roman and Carthaginian constructions policies? High cost and the strains of war may have caused the Romans and Carthaginians to focus on building galley types that they knew would be of use in battle. The quinquereme was a tried and tested design. Ships built much larger than the quinquereme probably offered little in the way of a real tactical advantage. Further, they would have called for even larger numbers of rowers to crew them, a factor not to be overlooked when even one quinquereme needed some 300 men to row. Rome was oftentimes short of trained rowers, and the Carthaginians were not a numerous people to begin with, so both sides may have shied away from such larger, more manpower-hungry types.

The Successor kings, on the other hand, were engaged in a competition for international prestige and influence as well as purely military advantage. Perhaps having the biggest ships was as much a means of impressing the rest of the Hellenistic Greek world as it was of inflicting harm on one’s enemies. Demetrius the Besieger (337-283 BC), for instance, is known to have equipped his extensive fleet with fifteens and sixteens and he had at least one thirteen aboard which he entertained guests. Lysimachus of Thessaly (c.355-281 BC), answered Demetrius with the Leontophoros, a superheavy galley capable of carrying 1,200 fighting men on its deck in addition to the rowers and other crewmen. Later on, Demetrius’s son, Antigonus Gonatas, outdid Lysimachus with an even larger vessel.

The Naval Race Continues

Later generations kept up the naval race. King Ptolemy II of Egypt (309-246 BC) gathered together a navy of 17 fives, five sixes, 37 sevens, 30 nines, 14 elevens, two twelves, four thirteens, one twenty, and three thirties. Ptolemy IV (221- 204 BC) added to the contest with the introduction of the superlative “forty.” This vessel was enormous even by the gargantuan standards of the age and its shape is still subject to scholarly debate. Its full complement of rowers, sailors, and marines is said to have numbered around 7,000 men, which is comparable to the crew of a modern aircraft carrier.

Later generations kept up the naval race. King Ptolemy II of Egypt (309-246 BC) gathered together a navy of 17 fives, five sixes, 37 sevens, 30 nines, 14 elevens, two twelves, four thirteens, one twenty, and three thirties. Ptolemy IV (221- 204 BC) added to the contest with the introduction of the superlative “forty.” This vessel was enormous even by the gargantuan standards of the age and its shape is still subject to scholarly debate. Its full complement of rowers, sailors, and marines is said to have numbered around 7,000 men, which is comparable to the crew of a modern aircraft carrier.

The naval race among Alexander’s Successors, much like the Successors themselves, was extravagant, showy, and deeply competitive. In the end, though, the grand fleets of the East, like their armies, would be unable to prevent the region from eventually falling under the domination of the rising power of Rome.

Originally Published September 18, 2014

I am using some of the information here as a foundation to show that some of the historical “legends” had legs. One ancient story is that of the Iberians sailing to the “Island of the Seven Cities” sometime around CE 750. I think that I have “proven” that Newfoundland Island was an island of many cities even if it were not the Iberian Island of Seven Cities. It is important to establish that the people associated with that story had ships of sufficient characteristics to convey themselves, their effect and cattle, across the North Atlantic to North America.

My work would not fit the category of Warfare, but if you are interested, I have solved the “mystery” of the disappearance of the Celtic-Norse of Greenland (Circa 1418), and I have found ancient ships that are undoubtedly ships of the Great Chinese Flkeet of 1400 -1420.

Best wishes.

Ronald Ryan, DA, PhD.