By Michael D. Hull

Straddling the River Orne nine miles from the English Channel coast, the French medieval city of Caen was the focal objective of Lt. Gen. Sir Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

The Allied landings on five Normandy beaches had gone well that fateful Tuesday morning, despite fierce initial German opposition on the British beaches and a bloody setback for the U.S. 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions at Omaha Beach. The assault forces secured their bridgeheads and started pushing inland.

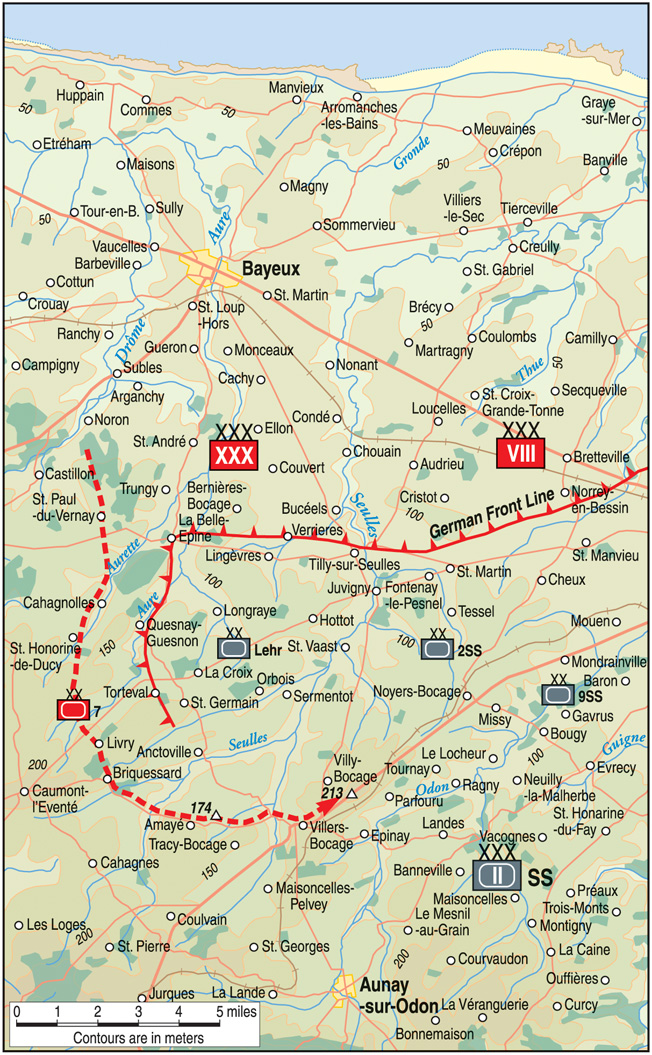

But they soon ran into concentrated resistance as the Germans swiftly drew the bulk of their panzer groups to the Bayeux-Caen-Falaise area, where the bocage country—a patchwork of small fields hemmed in by sunken roads, ditches, and thick embankments—strongly favored defense and hindered the Allied advance.

A costly slugging match developed, and a series of frontal assaults by British and Canadian armored and infantry units produced heavy losses and little headway. Caen, a key communications and transportation center viewed as the “hinge” of the Normandy campaign, was fiercely defended and would remain in German hands for a critical month.

General Bernard L. Montgomery, the Allied forces’ ground commander and leader of the powerful British 21st Army Group, ordered a bold “right hook” to try and envelop Caen. The thrust was led by Maj. Gen. G.W.E.J. “Bobby” Erskine’s 7th Armored Division, the famed Desert Rats, part of Brigadier Robert “Loony” Hinde’s 22nd Armored Brigade. Erskine’s tanks managed to penetrate as far as the town of Villers-Bocage, 10 kilometers southwest of Caen, but were halted there in one of the most astonishing actions of World War II.

Almost singlehandedly, one German soldier blocked the advance of the armored force and upset the British timetable by a month. He was Obersturmführer (lieutenant) Michael Witt-mann, commander of the 2nd Company of the 101st Heavy Tank Battalion, one of the spearhead squadrons of Col. Gen. Josef “Sepp” Dietrich’s I Panzer Corps. A slim, boyishly handsome man, the 30-year-old Wittmann was already a legendary figure in the Wehrmacht.

Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler: Hitler’s Elite Bodyguard

The son of farmer Johann Wittmann, Michael was born on Wednesday, April 22, 1914, at Vogelfal in the scenic Oberpfalz district in southeastern Germany. After graduating from high school, the quiet, industrious boy worked on his father’s farm and served in the Reichsarbeitdienst (National Labor Corps) for the first six months of 1934. That October, he enlisted in the 19th Infantry Regiment of the Reichscheer, the interwar German Army, and served for almost two years.

Discharged as a corporal in September 1936, the ambitious young man then joined the Waffen SS in April 1937 and was assigned to Sturm No. 1 of the elite Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler (LSSAH), the personal bodyguard formed by the German Führer in 1933. The hand-picked unit was led by the brutal but able Dietrich, a World War I sergeant major, early Nazi street brawler, and Hitler favorite. In late 1937, Wittmann received driver training, excelled in handling light and heavy armored cars, and joined the 17th Panzer Scout Company of the LSSAH. The unit was reduced in status to a panzer scout platoon in the summer of 1938.

Germany invaded Poland on Friday, September 1, 1939, and Great Britain and France declared war the following Sunday. Now promoted to unterscharführer (sergeant), Wittmann was in action from the start with the LSSAH assault gun battalion. During the brief Polish campaign and then in the German blitzkrieg sweep into Belgium, Holland, and France, he commanded a six-wheeled heavy armored car on reconnaissance sorties.

After German forces invaded the Balkans on April 6, 1941, Wittmann led an assault gun platoon in Greece, where his skill and gallantry earned him the Iron Cross Second Class. He soldiered against British Commonwealth troops and partisans in Greece until mid-1941 and then headed for another front where he was to come into his own as a warrior. Early that June, Wittmann and the LSSAH armored formations were shipped eastward to prepare for Operation Barbarossa, the German Army’s massive—and ill-fated—invasion of Russia.

Wittmann in Operation Barbarossa

When three Nazi armies swarmed across the Russian border on June 22, 1941, the LSSAH panzers rolled southward and Wittmann quickly distinguished himself as a tank commander in the first of many clashes with the Red Army. He knocked out Soviet tanks at an incredible pace, receiving another Iron Cross Second Class on July 12 for destroying six of them. He was wounded twice but stayed with his unit. During heavy fighting in the southern Rostov-on-Don area, Wittmann’s panzer demolished six Russian tanks in a single engagement. He was promoted to SS oberscharführer (technical sergeant) and awarded the Panzer Assault Badge and Iron Cross First Class.

In less than a year of action on the Eastern Front, Wittmann and his gunner, Balthasar “Bobby” Woll, were credited with 66 tank kills. Rated an excellent gunner, Woll was able to fire accurately while the panzer was on the move.

Recognized as officer material because of his battlefield leadership, Wittmann was ordered back to Germany for advanced training. Early in June 1942, he was accepted as an officer cadet at the SS Junker School in Bad Tolz, south of Munich. After being earmarked as a panzer instructor that September, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in December.

On Christmas Eve, 1942, Wittmann joined the 13th Company of the LSSAH 1st Waffen SS Motorized Division, which had been upgraded to a panzergrenadier division the previous autumn. The company was led by Hauptsturmführer Heinz Kling. The division trained at Paderborn, Westphalia, and Ploermel in northwestern France, and was equipped with the new Tiger I heavy tank. Wittmann was seconded to lead an assault gun platoon designated to protect the tanks from enemy infantry.

The division was transferred to the Eastern Front in late January 1943. Early that spring, Wittmann left the support platoon and rejoined the 13th Tiger Company. He soon began a remarkable association with one of the most effective tanks of the war.

Wittmann’s Tiger I

After invading Russia, the German armies had made spectacular advances against the unready Red Army and pushed close to the gates of Moscow. But the desperate Soviets mobilized, fought back, and rushed new weapons into production. When the 46-ton KV-1 heavy and 26.3-ton T-34 medium tanks appeared on the Eastern Front later in 1941, near panic swept through the German ranks. The formidable T-34 had revolutionary sloped armor, a powerful 76mm cannon, and a Christie suspension system.

Some German tank designers considered duplicating the T-34, but national pride overrode the idea. Despite the chaotic state of weapons procurement, the Third Reich’s armaments industry had to act quickly, so designs for new and larger panzers were rushed through by the Henschel and Porsche companies. The 43-ton medium Panther with a 75mm gun was built, and a modified Henschel design for a heavy tank was approved by the German Army’s weapons office. This was known as the Tiger E or Tiger I, and the production of 1,350 of them began in August 1942.

Everything about the Tiger I was impressive, and the Wehrmacht now had a tank to challenge the T-34 and the KV-1. It weighed 57 tons, had four-inch thick frontal armor plating, and mounted a long 88mm cannon and two machine guns. The Tiger’s speed was 23 miles an hour, and it carried a crew of five. The Krupp company developed the tank’s turret.

Lieutenant Wittmann and his Tiger I, crewed by gunner Woll, Werner Irrgang, Sepp Rossner, and Eugen Schmidt, went into action with the Waffen SS panzers on the Eastern Front in the summer of 1943. After the pivotal Russian victory at Stalingrad that January, Marshal Georgi Zhukov’s reinforced Red Army was defending a front stretching from Stalingrad to Orel, with a bulge in the Kursk area, while Field Marshal Erich von Manstein’s German forces held a smaller area adjacent to the River Donetz. The Soviet positions were exposed, inviting an assault by the Wehrmacht.

The Battle of Kursk

Equipped with the new Tiger and Panther tanks and two battalions of 67-ton Elefant tank destroyers, and supported by Luftwaffe bombers and fighters, a large German force launched Operation Zitadelle (Citadel), an attack on the Kursk bulge, on July 4. Operating with LSSAH panzers in the southern sector of the bulge, Wittmann wasted no time in deploying his Tiger to full advantage. On his first day of action, he destroyed two Soviet antitank guns and 13 T-34s and rescued Lieutenant Helmut Wendorff’s tank platoon, which had run into trouble. On July 7 and 8, Wittmann’s Tiger blasted two T-34s, two SU-122 self-propelled guns, and three T-60/70 tanks, and on July 12 his score was eight Soviet tanks, three antitank guns, and a field gun.

As many as 5,680 German and Soviet tanks and assault guns were involved in the week-long slugging match at Kursk, the biggest tank battle in history, and each side lost more than 1,500 of them. There, and at Kharkov to the south, Wittmann assumed command of a company of Tigers and put 30 Red Army tanks and 28 guns out of action. The German panzers and guns proved far superior to the Red Army’s weapons, but the Soviet armored reserves outnumbered Manstein’s.

Although it suffered an astounding 600,000 casualties at Kursk, the Red Army could afford to absorb the tank losses. On July 13, Manstein was forced to retreat in order to save his Army Group South, and four days later Hitler called off Operation Zitadelle. His high hopes for Barbarossa were dashed because his army never regained the strategic initiative on the endless Russian steppes.

Propaganda Tour in the Third Reich

Wittmann’s 13th SS Panzer Company withdrew for refitting and occupational duties at the end of July 1943, but early the following October the tank ace was back on the Eastern Front after the start of a Soviet autumn offensive. On October 13, his Tiger destroyed 20 T-34s and 23 assorted Russian guns. Wittmann commented that the Soviet antitank guns were more challenging and prized targets than tanks. Cited for demolishing a total of 88 tanks, self-propelled guns, and other vehicles, he was awarded the Knight’s Cross on January 14, 1944. The coveted decoration was usually reserved for generals and rarely given to enlisted men or junior officers. Wittmann and gunner Woll, who also won the Knight’s Cross and the Iron Cross, were eventually credited with having destroyed 119 armored vehicles on the Eastern Front.

Wittmann had established himself as the top-scoring panzer ace. He received a telegram from Hitler praising his “heroic actions in the battle for the future of our people,” his remarkable combat record was lauded on Nazi radio, and he was a national hero. After his unit was transferred to Mons, Belgium, Wittmann took time to marry his sweetheart, Hildegard Burmeister, on March 1, 1944. Gunner Woll, now a Tiger commander himself, was the witness for the ceremony.

The 30-year-old Wittmann made propaganda tours during the early spring of 1944 and visited the Henschel und Sohn armaments plant in Kassel. He thanked the workers for building the Tiger Is and showed great interest in the larger, up-gunned Tiger IIs, also known as King Tigers, then rolling off the assembly lines. On April 20, Hitler’s birthday, Wittmann was promoted to SS first lieutenant, and 10 days later proudly received Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross. Also that month, he was given command of the 2nd Panzer Company in Major Heinz von Westernhagen’s 101st Heavy Panzer Battalion.

Outgunning British Cromwells

As part of an armored reserve, which included the 12th SS “Hitlerjugend” Division and the Panzer Lehr Division, the LSSAH unit was stationed near the historic Normandy city of Lisieux, famed as the birthplace of Saint Therese, 27 miles east of Caen. The commander was able, 36-year-old Brigadier Theodor “Teddy” Wisch.

On Tuesday, June 6, 1944, the fateful day when the British, American, and Canadian armies landed on the Normandy coast, Lieutenant Wittmann took charge of a new Tiger tank and soon went into action again. The 101st Battalion rumbled toward the invasion front, savaged on the way by Allied fighter bombers. Wittmann’s company was reduced to six Tigers. Meanwhile, hastily deployed panzer squadrons fought hard to block British-Canadian armor and infantry units as they broke from their bridgehead perimeters and headed for the Bayeux-Caen-Falaise area.

On June 11, executing General Montgomery’s “right hook” aimed at enveloping strategic Caen, new Cromwell tanks of General Erskine’s 7th Armored Division attacked through the 50th Infantry (Northumbrian) Division and began an attempt to encircle the powerful Panzer Lehr Division near Tilly, west of Caen and north of Villers-Bocage. The Desert Rats swiftly captured the village of Verrieres-Lingevres, but the panzers counterattacked and a major armored battle raged there. The 27.5-ton Cromwells were outmatched by the Mark IV and V panzers.

On June 12, as part of Monty’s second all-out attempt to reach Caen, Erskine’s division rolled through a thinly held gap in the enemy lines between Caumont and Villers-Bocage. The British tankers were glad to be on the advance. An officer reported, “Here we are in this first week of battle, exploiting a possible breakthrough with very little opposition, an armored brigade in front and the infantry coming along in lorries. It was exciting to be on the move at such a pace.” But the Desert Rats’ elation was soon to be shattered.

Supported by Canadian infantry, the British 6th Armored Regiment assaulted remnants of the 12th Panzer Division at Les Mesnil-Patry. The British tankers ran into a nest of deadly 88mm flak guns and were slaughtered. Thirty-seven tanks were knocked out, only a handful of men survived, and the Canadians were repulsed in savage fighting. The action went on until June 14, but the German line held.

Villers-Bocage

At Tilly-sur-Seulles, Lt. Gen. Fritz Bayerlein, a vigorous, terrier-like Afrika Korps veteran, realized that his Panzer Lehr Division, rated one of the best in the German Army, was being outflanked. While the bulk of Erskine’s 7th Armored Division was pinning down his reduced force, a brigade-sized British armored group had penetrated as far as the Villers-Bocage area by the afternoon of June 12. Panzer Lehr’s left flank was in danger, and Bayerlein had already committed his reserves. He called for help, and it was not far off.

In the slow, agonizing British struggle to reach Caen, the market town of Villers-Bocage became a focal objective. It was of strategic importance to both the British and German armies. Situated at the head of the Seulles Valley, the town was the center of a road network and the gateway to Mont Picon, 10 miles south, and to the Odon Valley and Caen to the east. Brigadier Hinde sent units of his 22nd Armored Brigade to seize high ground northeast of Villers-Bocage, unaware because of an intelligence lapse that the enemy had the same objective.

Hastily deployed Tiger I tanks lay in wait for the British brigade. Among the panzer lineup, camouflaged and primed for ambush, were four Tiger tanks and two 25-ton Mark IV Specials of Wittmann’s 2nd Company of the 101st Heavy Panzer Battalion. The tank ace’s former gunner, Bobby Woll, was with him that day because his own Tiger was undergoing repairs.

Early on the morning of Tuesday, June 13, 1944, a spearhead tank-infantry column of Brigadier Hinde’s brigade advanced six miles behind the enemy lines and rolled unopposed into Villers-Bocage. The force comprised Cromwell and American-built Stuart light tanks, half-tracks, and Bren gun carriers of Lt. Col. Viscount Arthur Cranley’s 4th County of London (Sharpshooters) Yeomanry, accompanied by men of the 1st Battalion of the Rifle Brigade. Gaily dressed citizens cheered the surprised British troops, but the mutual joy was short lived.

The closely packed British column rumbled through the town and headed for Hill 213, dominating the national highway leading to Caen. The vehicles halted on the road leading to the summit, closing up nose-to-tail to allow room for relief point units to pass. The soldiers dismounted, stretched their legs, and brewed tea. Waiting behind the crest were Wittmann’s panzers and a strong infantry force. Unknown to Viscount Cranley’s tank crews and riflemen, they were being observed by the panzer ace, whose recognition of a quick kill was instinctive.

Wittmann took note of the closeness of the British vehicles, with high hedges on both sides of the road preventing them from maneuvering if attacked. He decided that he had no time to wait for the rest of his panzers and ordered their commanders “not to retreat a step but to hold your ground.” He would engage the enemy column on his own.

A First Defeat for the Desert Rats

Wittmann’s big Tiger burst from cover on the southern side of the Caen road and knocked out the rear tank of A Squadron of the London Yeomanry. Then he calmly drove along a parallel cart track with his Tiger’s 88mm cannon blasting Rifle Brigade tanks, half-tracks, and Bren carriers as he went. One half-track was struck with such force that it was hurled, blazing, across the road.

The British tankers and infantrymen fought back fiercely, but they were no match for the Tiger. Shells from the Cromwells bounced off the panzer’s thick armor, and A Squadron’s two six-pounder antitank guns had little effect. The British vehicles were turned into burning hulks. In five minutes, the audacious Wittmann disabled 25 British armored vehicles, bringing his score of combat kills to an incredible 44.

The rest of his company—three Tigers and a Mark IV Special panzer—soon joined in the fray. Outgunned and unable to maneuver, the British Tommies fought on. A Rifle Brigade six-pounder gun hit three of the enemy tanks, but Wittmann and his panzers kept the upper hand, destroying a total of 25 British tanks, 14 half-tracks, and 14 Bren carriers. The spearhead of the 7th Armored Division had been stopped cold. It was the first defeat suffered by the legendary Desert Rats.

Wittmann then coolly drove into Villers-Bocage, and dismounted British tank crews there were stunned at the sight. Their apparent lack of concern amazed gunner Woll, who said, “They’re acting as if they’d won the war already.” His commander replied, “We’re going to prove them wrong!” The Tiger lumbered along the town’s narrow main street and knocked out three Stuart tanks of the 4th CLY’s reconnaissance troop, four headquarters tanks halted on the eastern outskirts, and two unarmed command tanks of the 5th Royal Horse Artillery Regiment. The Tiger brushed off salvos from two six-pounder antitank guns, killed the crew of a stalking Cromwell, and exchanged fire with another Cromwell.

At 10 that fateful morning, the London Yeomanry’s A Squadron reported that it was surrounded by Tiger tanks, and half an hour later Viscount Cranley radioed that his position was untenable and withdrawal impossible. At 10:35 am, the squadron radio sets went dead.

The fighting raged on until dark in Villers-Bocage, where the gallant, flamboyant Brigadier Hinde had frantically organized makeshift defenses. Using anti-tank guns, PIAT rocket launchers, and sticky grenades at close quarters, infantrymen of the Royal Queen’s Regiment stalked an increased number of panzers and disabled 11 of them. But the furious day had belonged to the Germans, and the undergunned 7th Armored Division was ordered to pull back.

Cranley and many of his men were captured. Wittmann’s Tiger was damaged during the day’s fighting, but he was able to prudently withdraw into the cover of woods southeast of Villers-Bocage. His bold feat there had shattered the leading elements of Hinde’s 22nd Armored Brigade and thrown the Desert Rats temporarily onto the defensive. The British capture of Villers-Bocage—and Caen—was still a month away.

While the action at Villers-Bocage was a triumph for Lieutenant Wittmann, it was a disaster for the British, although they had fought bravely. The setback was blamed on shoddy tactics and a failure to reinforce the 7th Armored Division. “The whole handling of that battle was a disgrace,” commented General Dempsey.

On the recommendation of General Dietrich, Wittmann was rewarded on June 13 with prized Swords to his Knight’s Cross, making him the most decorated tank commander of the war. Promoted to captain a few days later, he was offered the position of instructor at an officers’ tactical school. But he refused and returned to the Caen front.

Stalling the Allied Advance

The fighting raged on, and the LSSAH and Hitlerjugend panzer groups, though suffering heavy losses, played a major role in resisting the British and Canadian armies as they pushed doggedly toward Caen and Falaise. The I Panzer Corps’ divisions delayed the fall of Caen (a D-Day objective), thwarted Montgomery’s bold attempts to outflank the city in Operations Epsom and Windsor, and brought his massive armored assault codenamed Operation Goodwood to a costly halt. Subsequent delaying actions by the LSSAH and Hitlerjugend armor southeast of Caen between July 20 and August 18 did much to frustrate Monty’s timetable.

By early August 1944, Captain Wittmann’s Tigers were battling units of the 4th Canadian and 1st Polish Armored Divisions as able, hard-fighting Lt. Gen. Guy G. Simonds’s Second Canadian Corps attacked along the Caen-Falaise road during Operation Totalize. After a punishing bombardment by 1,020 Royal Air Force Bomber Command Avro Lancasters and Handley Page Halifaxes on the night of August 7, the British 51st Highland and Canadian 2nd Infantry Divisions, supported by Cromwell and Sherman tanks, pushed along a narrow six-mile sector between the villages of St.-Martin and Soliers, south of Caen.

Inexperienced men of the German 89th Infantry Division panicked and fled, much to the consternation of Oberführer (colonel) Kurt “Panzer” Meyer, whose 12th Hitlerjugend Division was nearby. Brandishing a rifle, the hardened, cigar-chewing veteran of a dozen campaigns, including two years in Russia, strode to the middle of the Caen-Falaise road on the morning of August 8 and rallied the retreating infantrymen. He temporarily checked the Allied advance but was in no position to halt the entire Canadian II Corps. Meyer’s division had been whittled down from 214 to 48 serviceable panzers. Maj. Gen. Wisch’s LSSAH Panzer Division was also now seriously understrength.

The road to Falaise was almost open, but green Canadian tank commanders were exhibiting caution. Realizing that his sector faced collapse before the weight of the Canadian corps, Meyer decided to launch a spoiling attack. He struck at midday on August 8 with Hitlerjugend Division panzers while General Simonds was getting ready to commit his Canadian 4th and Polish 1st Armored Divisions. A battle group of eight Tigers and 14 Panthers headed for the strategic village of Cintheaux, and 20 Tigers rolled toward St. Aignan-de-Cramesnil, to the north.

As Meyer’s groups moved, almost 500 U.S. Eighth Air Force B-17 Flying Fortress bombers blasted the area, and stray bombs hit the panzers and the Canadian and Polish armor. In fierce fighting across rolling farmland, one of Meyer’s columns wrested Cintheaux from the Canadians, and his other force clashed with Maj. Gen. Stanislaw Maczek’s Polish Shermans. Six panzers were destroyed, but the Waffen SS gunners disabled 26 Polish tanks. Meyer’s assault was halted, but Operation Totalize was temporarily derailed.

Captain Wittmann’s Final Battle

Captain Wittmann was in the thick of the action, facing his greatest challenge and his last engagement. At noon that day, Meyer had ordered him to lead four of his 2nd Company Tigers in supporting a thrust by Major Hans Waldmuller’s battle group toward St.-Aignan, east of the Caen road. The German tankers’ odds against the massing Allied Shermans and Cromwells were precarious. Meyer shook Wittmann’s hand, wished him luck, and reported later, “The enemy artillery laid concentrated fire on the attacking panzers. Michael Wittmann’s panzer raced right into the enemy fire. I knew his tactic during such operations: get through, don’t stop, into the dirt and reach a free field of fire.” All of the panzers lumbered into the fray with cannons and machine guns firing, followed by Waldmuller’s grenadiers.

Around 12:20 pm, Meyer ordered Waldmuller and Wittmann to counterattack northward with all available resources. Because his own vehicle was then being repaired, the panzer ace was in an unfamiliar tank—Colonel Westernhagen’s command Tiger, which carried 30 fewer cannon shells due to extra radio equipment. Wittmann’s driver that afternoon was Heinrich Reimers. Advancing to engage a superior number of Canadian Shermans and Fireflies (Shermans mounting 17-pounder guns) north of Cintheaux, Wittmann was on an impossible mission.

Moving off from the cover of a hedge near Les Jardinets, east of the Caen road, Wittmann’s four Tigers rumbled north-northwest. They paused in shallow gullies to fire long range at some Shermans of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers and knocked out several. Wittmann then deployed his panzers in line ahead to minimize the target they presented, but this rendered them vulnerable to northeastern orchards south of St.-Aignan, which Shermans and a Firefly of A Squadron of the 1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry had just occupied. The British tanks were behind a tall hedgerow near the village of Delle de la Roque, east of the Caen road.

The No. 3 Troop’s Firefly, the only tank there capable of stopping a Tiger, moved to the southern edge of an orchard to get a better field of fire. Wittmann’s panzer closed in around 12:40 pm, and the Firefly started shooting. Simultaneously, Fireflies of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers and the 144th Regiment of the Royal Armored Corps opened fire from west of the Caen road. Twenty-one-year-old Trooper Joseph W. Ekins, the gunner of the No. 3 Troop Firefly, loosed two shots at the rear Tiger, and it brewed up. With another round he exploded the second German tank.

A Squadron’s Shermans rumbled out of the orchard and blasted Wittmann’s command Tiger. The 75mm shells failed to pierce the panzer’s armor, but nevertheless caused damage, and it veered off erratically and ground to a halt near the main road. Trooper Ekins fired two shells, and the crippled Tiger burst into flames. At the same time, Fireflies of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers and the 144th Regiment also zeroed in on the area.

Wittmann and his four crewmen perished in the inferno. The legendary panzer ace had met a fitting warrior’s death. “He was a fighter in every way; he lived and breathed action,” eulogized General Dietrich.

Final Resting Place in La Cambe

Almost 40 years after his death, Wittmann’s remains were found in a communal grave near the Caen-Falaise road at Gaumesnil, just north of Cintheaux, in March 1983. After positive identification was made from dental records by the German War Graves Commission, the remains of the panzer hero were reburied in the German Soldiers’ Cemetery at the village of La Cambe, a few kilometers southwest of Omaha Beach on the Normandy coast.

The boyish, unassuming Trooper Ekins, a Bedfordshire native and veteran of the D-Day landings, sought no credit for killing Wittmann, nor did he express regret. He said simply that the panzer ace “was in someone else’s country without being asked” and got what he deserved. Ekins died on February 1, 2012, at the age of 88.

Updated Feb. 6, 2017

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments