By Gregory Peduto

In the opening months of 1942, German U-boats pushed Allied supply lines to the breaking point. In the month of January, Axis submarines claimed over 20 Allied vessels including a tanker just 60 miles off the coast of Long Island. How could German submarines operate at such long ranges along the nation’s coastline? The U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) reasoned that freebooting American fishing vessels were resupplying these marauding subs somewhere off the coast of Long Island. But why?

The Navy hypothesized that these fishermen were either ex-rumrunners put out of business by the end of Prohibition or a massive conspiracy of enemy agents nestled within the port of New York. The task of uncovering the plot fell to 40-year naval veteran Captain Roscoe MacFall, chief intelligence officer of the Third Naval District, a region that encompassed New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

The captain needed to act quickly, for the Allied war effort was struck a $5 million blow on February 9, 1942. At 2:30 pm fire engines wailed and thousands of workers scrambled through dense smoke to Manhattan’s Pier 88. On that tragic day, a suspicious inferno devoured the French-built superliner Normandie.

Amid the toxic fog, fireboats dumped hundreds of thousands of gallons of water onto the conflagration. The strategy proved disastrous, for the excess water pitched the groaning ship into a 30-degree list that panicked stunned onlookers.

The loss of the Normandie represented a catastrophic defeat for American forces. Seized from the Vichy French and renamed the Lafayette, the militarized mega-liner was as big as she was fast. Capable of carrying 10,000 troops, the blue-ribbon vessel could traverse the Atlantic in only four days time.

The Navy suspected Nazi foul play. MacFall put little stock in official FBI investigations that suggested an erratic spark from a worker’s blowtorch ignited the blaze. The loss of the vessel was not only a physical defeat but also a symbolic one that highlighted a weakness in America’s strongest port.

Turning to the Mob to Hunt Saboteurs

From this strategic point, men, arms, and munitions would be shuttled to the front lines. To starve out the British, German Admiral Karl Dönitz, commander of the Kriegsmarine U-boat arm, calculated that U-boats needed to sink 800,000 tons of Allied shipping a month. Current losses at that point exceeded 650,000 tons a month. If enemy agents provided enough assistance to paralyze this lifeline, the war would be over.

Plainclothes Navy operatives descended upon the New York docks seeking information. With their best Jimmy Cagney impersonations, Ivy League-educated naval officers crept into the raucous haunts frequented by longshoremen.

The stevedores met the agents with a threatening brick wall of silence. The officers were incapable of understanding the lawless tight-lipped culture of the docks. On the wrong side of the law for most of their lives, some of the ship workers mistrusted anyone in uniform, whether they were naval officers or meter maids. To make matters worse, mob-controlled longshoremen regularly doled out gaff beatings to inquisitive cops and reporters.

Only the American Mafia claimed an utter dominance of the docks. ONI Warrant Officer Maurice Kelly remembered, “Union officials and people in illegal operations along the waterfront had as much influence with conditions on the docks as the shipping people themselves, and, in many cases, more.” The Navy wanted the Mafia’s help, but what would be the ramifications of turning to an organization predicated on murder, extortion, and drug dealing?

Time was running out for MacFall as the Navy moralized over the implications of enlisting the mob. Between February and May, Nazi torpedoes sent more than 100 ships to the bottom, and the death toll was rising fast. The easy pickings inspired the Kriegsmarine to christen the first six months of the war the “Happy Time.”

Director of Naval Intelligence, Rear Admiral Carl Espe, later reminisced, “The outcome of the war appeared extremely grave. In addition, there was the most serious concern over possible sabotage in the ports. It was necessary to use every possible means to prevent and forestall sabotage….” Someone on the docks was feeding the Nazis information, and only the mob had the power to hunt down the guilty party.

The Sicilian Mafia’s Grudge Against Mussolini

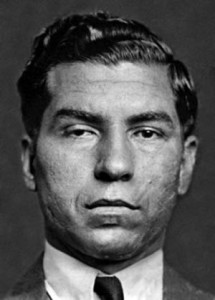

ONI held strong reservations over an alliance with the Mafia. Could Italian criminals even be trusted? Judging by the example set by master of intrigue, Vito Genovese, probably not.

After fleeing to Italy to avoid a murder prosecution in 1937, Genovese grew close to Mussolini by befriending his son-in-law and foreign minister, Count Galeazzo Ciano. The shrewd Genovese courted Mussolini by donating $250,000 for the construction of a Fascist party building.

The hoodlum grew so cozy with Il Duce that he soon dispatched his hitmen to assassinate New York newspaperman Carlo Tresca, a vocal critic of the Italian regime. For his work, Mussolini awarded Genovese the Commendatore del Re, the highest civilian honor in Italy, but Genovese was as apolitical as he was amoral. Capable of shifting like a feather on the political winds, the wily mobster held a reputation for double-crossing friends with impunity. The gangster felt no affinity for the fascist dictator and saw him only as a means to an end.

After weeks of intensive research, MacFall discovered that Genovese was an anomaly. The Mafia represented the most antifascist organization in the world. Under Mussolini’s savage purges, Sicilian mafiosi were bombed, machine-gunned, and arrested in droves. Many of the founding fathers of the American Mafia had fled their homeland because of the attacks.

Project Underworld

Time had run out for the Navy. On March 7, 1942, Captain MacFall met with New York District Attorney Frank Hogan to discuss striking a deal with organized crime. Hogan in turn put the captain in contact with the head of the New York Rackets Bureau, Murray Gurfein.

What followed the meeting was one of the most unusual episodes of the war, and it remained a secret until 1977, when author Rodney Campbell uncovered the classified 1954 Herlands investigative report while organizing Governor Thomas E. Dewey’s archives. The 101-page report summarized over 3,000 pages of testimony that detailed the Navy’s involvement in what was dubbed “Project Underworld.”

MacFall assigned the day-to-day operations to Commander Charles Radcliffe Haffenden, the debonair swashbuckling leader of ONI’s B-3 investigative unit. Commander Haffenden’s style did not end with his personality. Project Underworld would be run from a series of posh suites in the Times Square Astor Hotel.

Around him the commander assembled a dedicated team of colorful agents, many of them Italian-Americans versed in the Sicilian dialects spoken by the underworld. Among these men were Lieutenant Anthony Marsloe, a man fluent in Italian, Spanish, and French; Lieutenant Joseph Treglia, a former bootlegger now in charge of breaking and entering operations; and Lieutenant Paul Alfieri, a safecracker.

Recruiting Crime Lord Joe Socks

On March 25, Hogan and Gurfein offered Haffenden his first contact in organized crime. The team suggested the czar of Manhattan’s Fulton Fish Market, Joseph “Socks” Lanza. A made member of the Luciano crime family, the hulking 200-pound Mafia bulldozer earned his handle socking anyone who disagreed with his edicts. His criminal history stretched back to 1917 with arrests for homicide, burglary, conspiracy, and extortion.

The beefy fishmonger’s resume in the Federal Bureau of Narcotics International Offenders’ Black Book added, “A powerful and feared member of the Mafia in NYC. Has been one of the most accomplished terrorists in connection with labor racketeering in the lower east side Fulton Fish Market area.” Socks’s clammy grip over the United Seafood Workers Union stretched from Maine to Florida.

With a simple nod of his massive head, an entire fishing fleet would dump its catch to inflate market prices. For companies that failed to bribe the racketeer, their fish were left on the docks to rot. Those who continued to disobey orders faced beatings, arson, and death.

If anyone was capable of ferreting out sailors supplying Nazi submarines, it was Joe Socks, but how could the Navy approach a man bound by the oath of omerta? Haffenden knew a Navy officer stood little chance of penetrating the lawless fish market. Rather than walk through Lanza’s front door, he chose a surreptitious route and phoned the mobster’s attorney, Joseph Guerin, to set up a clandestine meeting.

Lanza needed to be careful. The hoodlum was currently on trial for extortion. Just meeting with a naval officer and a member of the district attorney’s office could earn the mafiosi a pair of cement shoes and a one-way ticket to the bottom of the East River.

During the meeting, Gurfein pleaded with Lanza. He begged, “It’s a matter of great urgency. Many of our ships are being sunk along the Atlantic coast. We suspect German U-boats are being refueled and getting fresh supplies off our coast …You can find out how and where the submarines are being refueled.” Surprisingly, the gangster jumped at the opportunity.

The district attorney’s office had wire-tapped the mobster’s phones to ensure his loyalty. To their horror, the bugs recorded conversations detailing Navy-inspired mayhem that included assaults, break-ins, and possible murders.

A Lookout System For Finding U-Boats

The next morning Lanza called his longtime associate Benjamin Espy, a former bootlegger who had served time in Lewisburg Penitentiary. Together the team questioned ship suppliers and demanded that any unusual purchases of food or fuel be reported to them.

The two gangsters moved onto the vessels themselves and set up a network of fishermen to keep an eye out for submarines. The fish racket bosses’ success startled the men of the B-3 investigative unit. Sensing the Mafia’s influential grip, Haffenden requested union cards to infiltrate his agents on long-range fishing vessels.

Socks responded by providing valuable cards used for no-show payoff jobs. The agents of the B-3 investigative unit roved far and wide under the protective wing of La Cosa Nostra. They sailed aboard mackerel fleets bound for Maine, Florida, and Newfoundland. Shockingly, these fleets served as the first line of U.S. defense against submarines.

Captain MacFall later recounted, “Some of the larger fishing fleets had their own ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore telephones, including codes used to guide the ships of one fleet to places where the catch was good … Naval Intelligence worked out a confidential cooperative agreement and code with them as a part of the submarine lookout system.” Lanza and Espy even traveled on their own “fishing” missions, recruiting informants as they went.

Joe Socks also provided cover for much more sensitive missions. Lieutenant Joseph Treglia, leader of B-3’s breaking-and-entry teams, wanted agents placed within several Manhattan buildings and a foreign consul’s office. The teams obtained entry through Lanza’s connections with the buildings’ superintendents and the Elevator Operator Union.

The units consisted of 11 men and included a lock expert, a letter opener, a photographer armed with a miniature camera, and a radio- equipped security detachment. These black-bag jobs helped uncover several German espionage rings across the nation.

Dealing With Subversive Union Leaders

There was no doubt that Socks enjoyed playing his role of secret agent as much as Commander Haffenden enjoyed playing the role of mob boss. In one instance, the commander received word that Harry Bridges, a subversive West Coast union leader, was headed to New York to stir the union pot.

Wiretaps revealed a startling conversation between Haffenden and Lanza. “How about that Brooklyn Bridge thing?” the commander asked in reference to the union leader. “I don’t want any trouble on the waterfront during the crucial times,” Haffenden continued.

“You won’t have any. I’ll see to that,” Lanza quipped.

A goon squad later caught up with Bridges in a popular dance hall. A savage beating sent the union organizer home without a peep. Pleased with the power his acolyte wielded, Haffenden pushed the beefy fishmonger’s connections to the limit, and the gangster eventually reached the ceiling of his power.

Lucky Luciano on Ice

The Luciano family revered Lanza, but the fish racketeer annoyed the other four crime families. To secure Brooklyn’s docks the Navy needed the approval of Albert Anastasia, a bloodthirsty figure known as the High Lord Executioner.

Socks balked at the prospect of facing Anastasia’s explosive temper and legendary trigger finger. Furthermore, Lanza lacked the influence to cross the ethnic divide. Irish gangsters controlled the Hell’s Kitchen slums surrounding the Hudson River piers and railway terminals. To organize the West Side docks, the Navy required the cooperation of Irish tough, Joseph Ryan, president of the International Longshoremen’s Association.

According to Lanza, there was only one man capable of “snapping the whip in the entire underworld.” That man was New York’s imprisoned emperor of vice, Lucky Luciano.

Born Salvatore Luciana just outside of Palermo, on the island of Sicily, the thin, almost frail, Charlie Lucky clawed his way to the top of the criminal world in little more than three decades. A prison psychiatrist later analyzed him as a highly intelligent, aggressive, egocentric, and antisocial type. Lucky earned his nickname in 1929 after surviving a brutal torture at the hands of a rival bootlegging gang. Left for dead, Luciano crawled to freedom and earned his moniker, but the beating left him permanently disfigured.

The Mafia leader rose to prominence during the 1930-1931 Castellammarese Mafia War after Luciano double-crossed two bosses and became the top Mafia don in the United States. After the Castellammarese War, Charlie Lucky overreached himself with a bold takeover of all Manhattan whorehouses. The scheme landed the hoodlum a 30- to 50-year prison rap courtesy of Thomas E. Dewey.

After the conviction, Luciano wasted away in the frigid recesses of New York’s Dannemora Prison on the Canadian border. The sentence put the crime boss on ice, literally. The distance from the city effectively severed Lucky’s communication with his mob.

Making Contact With Luciano

Haffenden needed Lucky but had no idea how to contact him. As in the case of Socks Lanza, the district attorney suggested that the Navy approach the imprisoned gangster’s attorney, Moses Polakoff. The lawyer bluntly stated that he no longer had any dealings with Luciano, but he knew of one man who had the exiled boss’s undying devotion. That man was Jewish racketeer Meyer “The Little Man” Lansky.

Unlike the Mafia, the Navy never questioned The Little Man’s patriotism. A staunch Zionist, Lansky’s hoodlums battled American Nazis in Manhattan’s streets long before the declaration of war. Lansky later recalled, “We got there that evening and found several hundred people dressed in their brown shirts. The stage was decorated with a swastika and pictures of Hitler … We attacked them in the hall and threw some of them out the windows. There were fistfights all over the place.” Extremely patriotic, the Jewish mob busted up Nazi meetings and offices all over the city.

Dannemora Prison’s remoteness posed another obstacle. The war effort could never be coordinated at such a distance. While Polakoff and Gurfein worked with Lansky, Haffenden moved to transfer Luciano.

The Navy proceeded with caution, for if the other four crime families caught wind of an unexpected prison reassignment, they might suspect Luciano had cooperated with the authorities. With this situation in mind, an ONI officer approached New York State Corrections Commissioner John A. Lyons with a letter detailing Project Underworld and a scheme to relocate Luciano and several decoy inmates to Albany’s Great Meadow Prison.

Lyons agreed to the arrangement, and the agent burned the letter. On May 12, 1942, Luciano and eight other convicts headed to Great Meadow as nine new prisoners filled their vacancies at Dannemora. Shortly thereafter, Lansky and Polakoff traveled to the penitentiary, and Lucky reportedly exclaimed, “What the hell are you doing here!” Lansky outlined Project Underworld, but Luciano worried about many variables.

First, the Navy offered no sentence reduction for the gangster’s crimes. Second, as an illegal alien the mobster faced deportation. If word of his alliance leaked out, a fascist lynching was sure to follow his homecoming. Despite these realities, Luciano’s control over his crime family was slowly slipping away. The freedom provided by the proposal offered the perfect cover for the boss to confer with his top lieutenants and regain his power.

Bringing the Waterfront Under Control

On June 4, Lansky, Polakoff, and Socks Lanza traveled to Great Meadow to plan their strategy. The meeting was a proud moment for Socks when Luciano gave the fish boss permission to “use his name” on the streets. Lansky oversaw the entire operation, serving as Lucky’s eyes, ears, and mouth on the outside. Luciano’s acting boss, political fixer Frank Costello, assured him that the family backed Socks on every step.

Within days, the underworld fell in line. First to join the alliance was the president of the International Longshoremen’s Association, Joseph Ryan, and his brutal enforcer Johnny “Cockeye” Dunn. A murderous cross-eyed fiend, Dunn would one day die in the electric chair. Next to throw in was the High Lord Executioner himself, Albert Anastasia. With Anastasia’s backing, no one could refuse the mob’s offers.

Longshoremen’s Association tough Jerry Sullivan later testified, “Lansky was solving the problem for the Navy on the waterfront by the visible deployment of some of the most ruthless gangsters in the city. It was expected that the mere appearance of these men on the piers would serve as a deterrent, a warning to cooperate with the United States war effort or face the consequences.” Throughout 1942 and 1943, mob heavies came and went from the Navy’s elegant Astor Hotel suites, relaying orders and carrying out missions.

Haffenden then controlled a mercenary shadow army stocked with street brawlers, thumb breakers, murderers, smugglers, and international kingpins. Legs and arms were occasionally broken, and, gangsters being gangsters, the hoods often got a little carried away.

When Commander Haffenden sent Cockeye Dunn to investigate two suspected German agents, the Irish hoodlum took the men for a gangland one-way ride. Wiretaps recorded Dunn’s chilling report, “They’ll never bother us again.” The Navy frowned upon unauthorized killings, but it was impossible to keep a mad dog like Dunn in check.

Meanwhile, the visiting list at Great Meadow read like a copy of Who’s Who in American Crime. The autographs of Meyer Lansky, Bugsy Segal, Frank Costello, and Joe Adonis all graced the guestbook. Under the Mafia’s watchful gaze, not a single act of sabotage, labor strike, or suspicious fire occurred for the rest of the war.

F-Target Section: Planning the Invasion of Sicily With the Mafia

With the ports secured and North Africa ready to fall to Allied forces, the Casablanca Conference convened on January 14, 1943, at the Anfa Hotel in Morocco. For 10 days, Churchill and his aides badgered President Franklin D. Roosevelt into submission over the next military objective. The conference closed with a decision that radically altered the course of Project Underworld.

Allied generals, admirals, and strategists prepared for a savage dagger thrust into the Axis underbelly, Sicily. Surprisingly, a deficiency of intelligence existed. Long considered an area primarily under British surveillance, the Navy lacked even the most perfunctory details on the island.

The president of the Naval War College, Rear Admiral William Pye, chalked the lack of information up to “a feeling among many Americans that intelligence duty is somewhat akin to spying and, therefore, in times of peace, is an undignified and unworthy occupation.” The mob had no such moralistic problems.

The machinery of Project Underworld quickly spun toward the new strategic goal. While still in command of the B-3 investigative section, Haffenden formed the F-Target Section, a group dedicated to gathering data on the invasion zone. Sadly, the Navy’s most ardent supporter would have to sit this mission out.

On January 29, 1943, Judge James Wallace smacked Socks Lanza with a sentence of 7 to 15 for six counts of extortion. The flabbergasted Haffenden cursed the decision. Naval Intelligence required Luciano’s help more than ever before. ONI’s spymaster summoned Meyer Lansky to relay the invasion plans at Great Meadow.

The Navy desired Sicilian nationals who knew the island’s terrain. They wanted pictures, postcards, maps, and any kind of information to help plan the amphibious assault. Of particular importance was a list of possible Sicilian mafiosi willing to join a guerrilla insurgent army.

Lucky loved the idea. His narcotics smuggling network had close ties with the Sicilians. The boss even volunteered to lead the Mafia resistance and offered his services, suggesting that he “was prepared to be parachuted into the island….” High Command vetoed the idea. They reasoned the release of an arch criminal could be a public relations nightmare.

Joe Adonis and George Tarbox

To gather topographic data, the imprisoned boss brought in his lieutenant, Joe Adonis. A strikingly handsome ruffian, Adonis racked up arrests for nearly every crime conceivable, but astonishingly his rap sheet never listed a single conviction. Adonis then brought the situation to the attention of Vincenzo Mangano, the elderly don of one New York’s five families. Among members of all the families, the old don held the closest ties to Sicily through his massive import business that traded in cheese, pasta, olive oil—and most importantly—morphine base.

Adonis hauled hundreds of Italians into Naval Intelligence headquarters. He even kidnapped a man who was once mayor of a village in the old country. Meyer Lansky later testified, “Sometimes some of the Sicilians were very nervous. Joe would just mention the name of Lucky Luciano and say he had given them orders to talk. If the Sicilians were still reluctant, Joe would stop smiling and say, ‘Lucky will not be pleased to hear that you have not been helpful.’” The threats worked, and the information poured in.

To make sense of the gathered data, Target Section enlisted civilian agent George Tarbox. A cartographer and artist by trade, Tarbox crafted an enormous four-by six-foot map of Sicily with a clear plastic overlay that detailed strategic points in India ink. The overlay marked airfields, naval bases, and power plants. With the intelligence survey completed, the Sicilian D-day, Operation Husky, loomed large.

Project Underworld Commandos Land in Sicily

By May, Project Underworld was winding down. The ports were safe thanks to the mob’s brutal tactics, and the Mafia provided intelligence for the assault on Sicily. With no work left for Haffenden’s most skilled operatives, they embarked on a bold new endeavor.

In preparation for the assault, ONI formed a pair of two-man commando squads with two alternates from Project Underworld operatives. The squads included Lieutenant Marsloe, Haffenden’s language expert; Lieutenant Titolo, B-3’s former analyst; Lieutenant Alfieri, the commander’s safecracker; and Ensign Murray, a former police officer.

On May 15, 1943, the teams boarded a plane and flew to Mers-el-Kebir, Algeria, for the Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps commando school. The operatives took with them a list of names provided by their underworld associates. The list, which according to the Herlands report proved 40 percent effective, contained the names of imprisoned mafiosi, hill country bandits, and deported American gangsters.

Just three hours before midnight on July 10, 1943, the fishing villages of Licata, Gela, Marzamemi, and Pachino awoke to a cacophonous roar of Allied warships commencing a pre-invasion bombardment. Within three days, General George S. Patton’s Seventh Army and General Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth Army put ashore 181,000 men, 600 tanks, 14,000 assorted support vehicles, and over 1,500 artillery pieces. Among the first to storm the beaches were Haffenden’s officers.

Agents Marsloe and Murray landed between Torre di Gaffe and Punta due Rocche with General Truscott’s 3rd Infantry Division and a Ranger battalion. Alfieri and Titolo put ashore in the Gulf of Gela in the midst of General Terry Allen’s 1st Infantry Division and two Ranger battalions. With lead flying all around them, the naval operatives donned civilian clothing and infiltrated the enemy lines.

Raid on Italian Naval Command

The agents recalled that Luciano’s name acted like a magic key that when spoken unlocked the hearts and minds of the island’s mafiosi. In one instance, Alfieri located a cop killer whom Luciano rescued from the electric chair by smuggling him to Italy. The island’s men of honor proved particularly useful for Alfieri, for they identified the headquarters of Italian naval command. Together with a posse of Sicilian bandits armed with shotguns and hunting rifles, agents Alfieri and Titolo raided the headquarters. Under the covering fire of his Mafia guards, Alfieri crept into the base.

Alfieri’s experiences breaking and entering during the New York phase of Project Underworld paid off. With the skills of a master cat burglar, he blew the enemy’s safe and seized hundreds of classified documents, codebooks, and maps. For his work, Alfieri earned the Legion of Merit.

While Titolo and Alfieri raided the naval headquarters, Marsloe and Murray set about building an insurgent army. Unfortunately, the plan never took root. The mafiosi were willing to fight, but the competitive race between Patton and Montgomery for Messina in an effort to cut off Axis forces on Sicily exceeded all expectations.

Destroying the Evidence

On July 22, Patton captured the Sicilian capital of Palermo just two hours before Monty. A scant 19 days later, Allied troops entered Messina and ended the Sicilian campaign and with it Operation Underworld.

The Navy immediately burned all evidence of its cooperation with organized crime. On the same day as the armistice, Charlie Luciano applied for executive clemency on the grounds of his cooperation with the Navy. His request was granted, and on January 9, 1945, the aging racketeer was released and deported.

No mention was made of stopping supposedly traitors supplying U Boats with fuel etc. or how the docks were free of enemy agents.

Dave