By Robert Barr Smith

Many of the prisoners knew this night was probably their last on earth. Amiens Prison had seen a great many judicial murders and much Gestapo torture and brutality, so except for those about to die, executions were routine. Most of those who died within these walls were simply patriots, members of the French Resistance movement, agents, and ordinary people who helped their occupied country against the Germans and their own prostrate government at Vichy. They were held in a separate part of the prison, the “German side.” The rest of the prison housed ordinary criminals.

Outside the grim stone walls a bitter February night closed down like a shroud. Those about to die knew there could be no assistance, no miraculous delivery. Locked in their cells behind the thick stone walls, surrounded by a German garrison, in a city saturated with collaborationist police and officials, they were far from help. There could be no rescue mission from outside. Besides, the resistance had been badly shattered over the last months, infested with informers, and those of its leaders not captured by the Gestapo or the French Milice were on the run or in hiding.

This was 1944, the year of the Allied invasion, and much depended on information from within France: data on transportation, defenses, even the location of the Germans’ launch sites for V-1 buzz bombs reaching out toward London. Effective sabotage was crippled. Most of the heavy-duty transmitters sending information to London were in German hands. The damage to the resistance apparatus must have crossed the minds of those about to die. Many were veterans, and among their fellow prisoners were at least one American and two Englishmen. Worst of all, one of the French prisoners was the heart and soul of the Somme resistance. If the Gestapo found out who he was and broke him, the entire network would crumble, and with it crucial pre-invasion intelligence and information on the German missiles. The Allied intelligence chiefs knew the danger, and frankly agreed that this man had to be gotten out … or killed.

The French underground fighters who remained free were well aware of the plight of their comrades inside the prison. They even weighed the possibility of an armed ground assault on the prison walls. They were a motley collection of shopkeepers, doctors, housewives, thieves, whores, and at least one pimp, but they shared a fierce patriotism. They would get their chance to help their imprisoned friends, but not in the way they imagined.

As time ran out, the underground weighed plans and the Amiens prisoners thought grimly about what awaited them, thought of family, prayed, and prepared themselves as best they could. Meanwhile, in England, a remarkable man and a remarkable collection of planners, pilots, and navigators were preparing an astonishing feat of arms, no less than an aerial jailbreak courtesy of the Royal Air Force.

The Raiders of 140 Wing

The RAF outfit laid on for the task was 140 Wing, comprising Squadrons Number 487, New Zealand, Number 464, Australian, and Number 21, British. From their air base at Hunsdon, near London, the wing was flying “no ball” raids, strikes against German V-1 launching sites across the Channel. These were veteran airmen; many of the aircrew had flown literally hundreds of missions into the hostile skies across the Channel. They were very good indeed. In fact, all three squadrons would be part of other daring strikes, including the March 1945 rooftop attack on the six-story Shell Building, Gestapo headquarters in Copenhagen. They left the building afire and were gone, covered by P-51 Mustang fighters, by the time the Germans could start to recover. A single plane was lost at zero altitude when it struck a building, but the Danish underground reported 151 Gestapo killed and some 30 Danes escaped.

The same squadrons also hit the Gestapo headquarters in Aarhus, Denmark, in October 1944. This raid, like the others, was truly an Allied affair. The aircrew were British, Canadians, Australians, and New Zealanders, and the covering Mustangs came from a Polish squadron. The target was not only the Germans in the building, but especially the mass of carefully collected dossiers on thousands of Danes.

In spite of bad weather, the raid went perfectly. The raiders struck their target hard, avoiding two nearby hospitals. Delighted Danes waved the V-for-Victory sign at the raiders, and on the run into the target a farmer plowing his ground came to attention and saluted as the de Havilland Mosquito bombers roared in toward the city and skimmed over the buildings as low as 10 feet. The raid was carried out without losses, except for a dented engine nacelle and one raider’s tail wheel left on an Aarhus building when the pilot closed in to return fire from a building window. One pilot had the memorable experience of watching one of a comrade’s bombs hit its target, come out through the building’s roof, and arch gracefully over his own aircraft.

The Top Secret Operation Jericho

The operation against Amiens Prison, codenamed Jericho, had been prepared in the deepest secrecy. Until a scale model of the Amiens Prison was unveiled on a table in the briefing room, none of the crews had any idea they were scheduled for the most audacious raid of the war, rivaled only by the Doolittle strike at Tokyo. Matter-of-factly their leader, Air Vice Marshal Basil Embry, told the aircrew that they were on their way to blow holes in prison walls deep in France so that prisoners inside could run to safety.

The whole idea might have seemed fantastic coming from about anybody but Embry, but he wore his credentials on his chest. He was a veteran of many missions into harm’s way. He was once captured but could not be held for long. He simply killed his German guards and ran for it, escaping over the Pyrenees. The Germans put a 70,000-mark bounty on him, dead or alive, so he flew later missions as “Wing Commander Smith,” even wearing a dog tag to that effect. Embry was a stern taskmaster, but a fine leader, intensely concerned about his men. When an assemblage of high-ranking officers pressed him to take the Vultee Vengeance divebomber for use, Embry had been adamant: “I will not be a party to my men being killed in the Vultee Vengeance.” And that was that.

They would have to attack the prison soon, Embry said, since some of the prisoners were slated to be executed in the near future. The group would be braving miserable weather, German flak, and a cloud of fighters, including the Focke-Wulf FW 190s of the Abbeville Boys. These were the pilots who painted the noses of their fighters yellow and followed the legendary Adolf Galland,who rose to the post of general of fighters. They were a formidable lot.

Percy “Pick” Pickard: A Gentle Giant

So was the man who would command the wing during the raid. Embry had been forbidden to lead, a bitter disappointment, but he had confidence in the man who flew in his place. Percy Pickard—“Pick” to his pilots—was the wing commander and himself a storied veteran of innumerable missions into the teeth of the Luftwaffe. Pickard had been an Army officer of the King’s African Rifles before the war but had transferred to the Royal Air Force. As it turned out, he and the RAF were made for each other.

He had been actively flying operational missions since 1940, including over 100 nocturnal flights into occupied France, landing little Lysander liaison aircraft and Hudson bombers in pastures to deliver agents and supplies. In 1942, he led the bombers that dropped paratroops who raided the German radar station at Bruneval, shot some Germans, took the set apart, and made off by sea, taking a vital part back to England. He also flew conventional missions: shot down on a bombing mission in the Ruhr, Pickard crash-landed in the North Sea, where he and his crew bobbed around in a rubber boat—in a minefield—until their little craft drifted clear and they could be rescued. Pickard stood over six feet four, but he was nevertheless a gentle man who loved animals of all kinds, from rabbits to snakes, and particularly his English sheepdog Ming.

Dead serious about their job, professional to their boot-heels, the men of the wing nevertheless had a light side, very much in the RAF tradition. Visited by the king and queen at an airport at which they had been earlier stationed, the flattered Pickard was asked by the king the significance of a track of black barefoot prints leading up the mess wall and across the ceiling. Pickard, realizing that appropriate wall and ceiling cleaning had been overlooked, had to admit that the tracks were his, hoisted up by his pilots during an especially jovial party after the highly successful Bruneval raid, his feet covered with shoe polish. “But what,” said His Majesty, “are those two especially large blobs in the center of the ceiling?”

“I regret to say, sir,” said Pickard, “that those are the marks of my bottom.” He apologized, but he and his pilots found that the royal couple had a sense of humor.

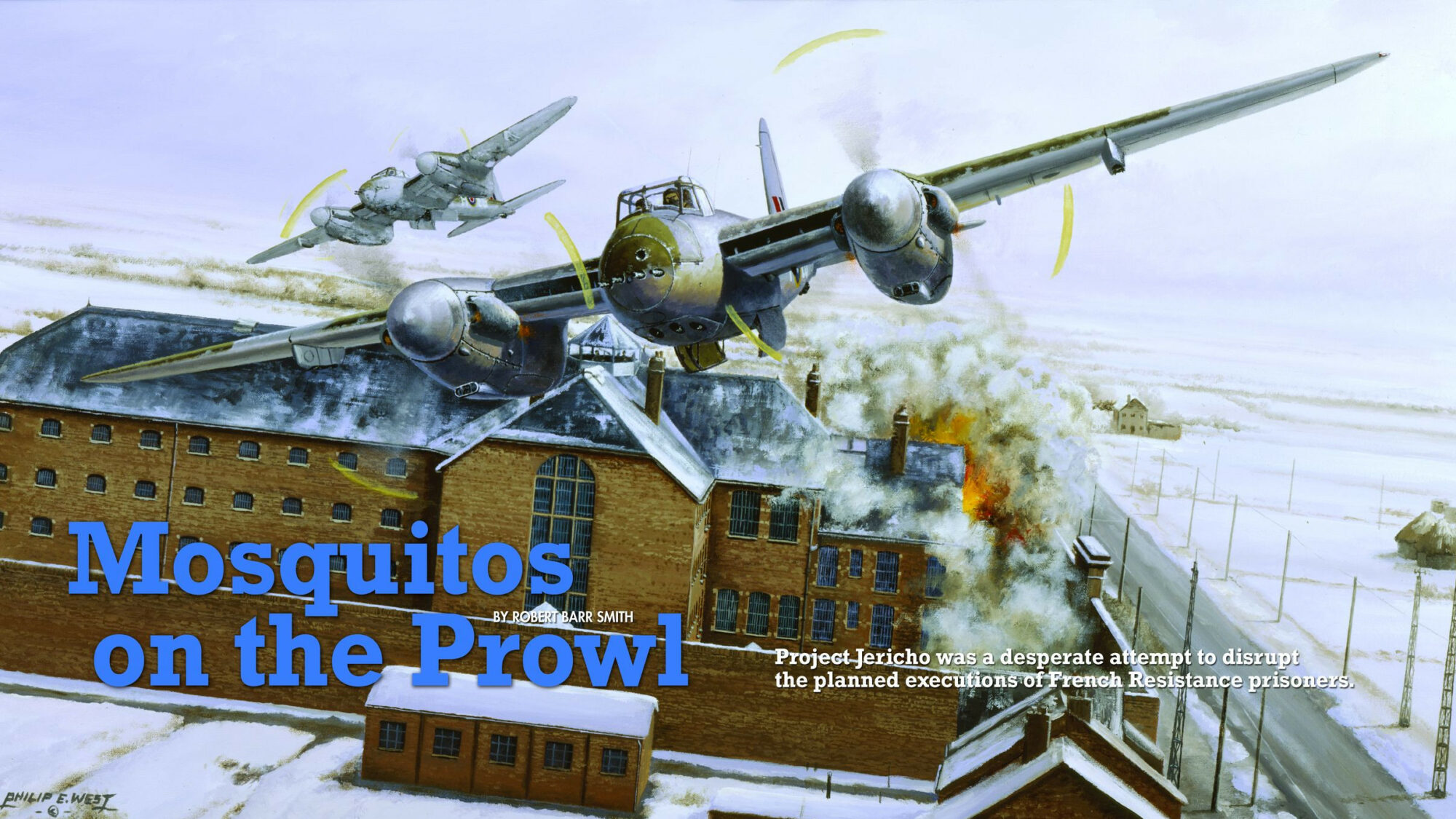

The de Havilland Mosquito

All three squadrons of the raider group flew the de Havilland Mosquito, probably the finest fighter-bomber of the war. The “wooden wonder,” as she was called, was constructed largely of plywood from Canada and balsa wood from Ecuador. Her parts were put together in woodworking shops all across Britain—“every piano factory” Göring grumbled, when the Mosquito proved faster than any German fighter of the day. Then the final assembly took place at de Havilland, where the sections were put together in concrete molds, the glue bombarded with microwaves to hurry the drying.

Even the early prototype reached a speed of 392 miles per hour, an unheard of speed for the day. The Mosquito’s power came from a pair of Rolls Royce Merlins, the same engine that drove the Supermarine Spitfire and made an ordinary airplane called the Mustang into a long-range wonder, the finest single-engine fighter of the war. The Mosquito appeared in all sorts of configurations besides light bomber. It flew as a photo reconnaissance aircraft, radar-equipped night fighter, heavy bomber escort, and one version, armed with rockets and a 57mm cannon, was developed to stalk German U-boats. During the war they flew more than 28,000 missions, one aircraft flying 213 sorties. Mosquitos struck Berlin in early 1943, giving lie to Göring’s boast that no British bomber would ever reach the capital of Nazi Germany.

The Mosquito carried a prodigious sting. The airplanes that would attack the prison were armed with four machine guns and four cannon in addition to their bomb loads. Much thought had gone into those loads, and especially into how the bombs were to be dropped. Since the idea was to blow holes in the walls through which the prisoners could run to escape, and the RAF was coming in on the deck—“naught feet” as the pilots put it—the Mosquitos were in effect skip bombing and using delayed action ordnance at that. They had to hold a speed well below what the airplane would do and use great care to leave space between waves so that the bombs of the wave ahead of them would not go off before the next wave flew into the explosions of British bombs ahead of them. The impact generated by the bombs would also, the planners hoped, shake open the locks on cell doors or spring their hinges.

Perfect Target For a Low-Level Raid

One thing favored the attackers besides their experience and the quality of their aircraft. The ground around the prison was relatively flat and free of trees, houses, or other obstructions, making low-level attack possible. They would go in in waves of six airplanes on a front of about 100 yards. Each aircraft would drop its load of four bombs at once. If one wave failed to demolish its target, the next wave would follow up and bomb it. Since the bombs carried delay fuses, the later waves had to be sure they did not follow too closely behind the aircraft ahead of them.

Embry, Pickard, and their crews knew there was a substantial chance of civilian casualties inside the prison, but there was no help for that if the escape was to succeed. The French underground knew it too, but was ready to help. The handful of resistance leaders alerted to the raid knew only that if and when it came it would be at midday. They collected bicycles, men, and vehicles near the prison around noon each day, ready to hide escapers and spirit them away. They included a stock of weapons, in case they had to rush gaps in the walls to help prisoners out to freedom. There was also a vast stock of identity documents, stolen or expertly forged, many with real seals.

The motor vehicles were Gazogenes, which ran grumpily on gas from a wood-burning contraption on the rear. It then pumped the gas into a peculiar looking tank perched on the roof. They were ungraceful and ran at a glacial pace, but they were all that was available to the French civilian population and at least they would not attract unwanted attention from the Germans or the Vichy police.

“Just Follow Me- You’ll be All Right”

February 19 dawned cold and thickly overcast, miserable weather into which no civilian aircraft would ever have ventured. Nevertheless, the raid was a go, driven by the ominous knowledge that more delay, even a day, might be the deaths of more prisoners at Amiens. One frightening piece of information passed to the resistance indicated that the execution would be on the 19th, and a mass grave had already been dug.

The wing’s attack was minutely orchestrated. The first squadron, 487 New Zealand, would split into two three-plane sections, each section to strike a different side of the walls. The Australians, also flying in two three-plane sections, would follow, attacking the corners of the main building. Six aircraft of 21 British were in reserve, ready to hit anything that was not destroyed or that Pickard ordered. He would orbit over the prison, identifying targets that needed more work, and a photo recon Mosquito would record the damage.

Each squadron would be covered by a squadron of burly Hawker Typhoon fighters. The big Typhoon, lineal descendant of the famous Hurricane, was designed as an interceptor. Instead it won its spurs as a low-level fighter and fighter-bomber: fast, armed to the teeth, a full match for the Luftwaffe’s Focke-Wulf FW 190 at the altitudes at which the Mosquitos would operate.

Pickard would watch for prisoners running through breaches in the walls, a sure sign of success. But if, he said, there were no escapers, 21 Squadron would be ordered in to bomb the jail itself. “We have been informed,” he said, “that the prisoners would rather be killed by our bombs than by German bullets.” It was something nobody wanted to do, but 21 was grimly prepared to strike the heart of the prison. There would be, he added, complete radio silence, and anybody who brought a bomb back to England would answer to him personally. And when someone asked about the precise course, the answer was vintage Pickard: “Bugger the course. Just follow me—you’ll be all right.”

The three squadrons took off into the murk of a miserable morning. It was snowing over southeastern England, but meteorology held out hope that the weather would improve once they reached France. At the start, it could not have been worse. The snow poured in against the Mosquitos’ canopies, clouds were down to 100 feet or so, and there was no hope of keeping formation. Several aircraft lost all touch with the others, including Pickard himself, and two Mosquitos narrowly avoided collision. Four crews were hopelessly lost, and at last had to turn back. They could not reach the prison in time to meet the exacting timetable of the raid.

Still another pilot lost an engine over France. Flying too slow to press on, he jettisoned his bombs and turned for home. Hit by flak on the way, with only one arm and one leg working, blood streaming from his neck, he hung on grimly. His observer managed to give him a shot of morphine, and he flew for home. Miraculously, he would make it. The rest pressed on, flying so low that their propwash kicked up great clouds of snow, skimming so near rows of power poles and lines of poplars that some of the Mosquitos had to raise one wing to avoid collision.

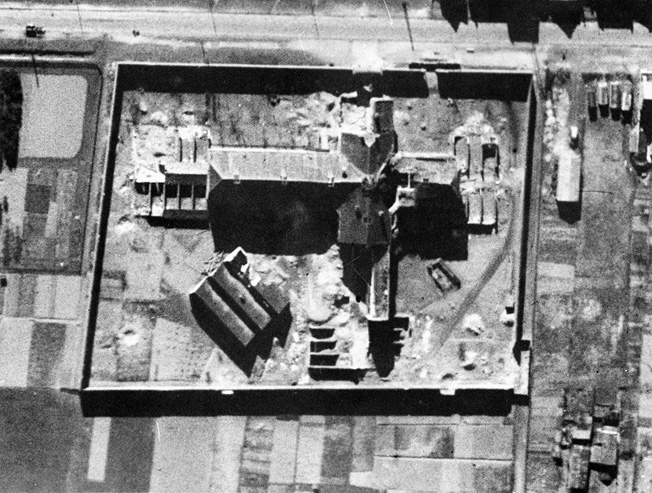

Breaching the Walls of Amiens Prison

The attack went in as planned, the aircraft skimming over the walls as they climbed after their drop. As great breaches appeared in the walls, little figures began to run for open country, sprinting for their freedom through the gaps. “You could tell them from the Germans,” said one RAF man, “because every time a bomb went off, the Germans would dive to the ground, but the prisoners kept on running like hell.” The bombs blew several small breaches in the north wall of the prison, a big one in the south wall, and an enormous hole where the west and north walls came together.

One aircraft dropped its load against the guardhouse and wall and climbed hard, skimming over a sort of gargoyle figure on the wall. Climbing away, they watched one bomb blow in the guardhouse, two more in the wall.

Some of the guard force lay dead or wounded in their mess hall; others wandered aimlessly through the ruins. Meanwhile, two prisoners —one a professional thief who picked the locks on the filing cabinets—were busily burning prisoner dossiers in the commandant’s office. Two more—one a professional burglar—paused in their flight long enough to burgle the Gestapo headquarters, knife a guard, crack the safe, and burn more heaps of files.

The great escape went on, prisoners by the hundreds running to nearby streets where they piled into the Gazogene fleet and vanished. Some—as many as 100—changed clothes in commercial vans thoughtfully parked for the purpose. Prisoners helped each other without distinction as to which side of the prison they came from. There were no criminals running from the building, no political prisoners, only Frenchmen. Some stripped guards’ bodies of their uniforms, becoming instant Germans. One, equipped with a white cane, tapped his way to freedom as a “blind man.”

A team of nine resistance members, including at least one prostitute, raided several stores, led by a professional thief called Violette Lambert … at least that was one of her names. Many of her team were also professional criminals, the women with bags carried under their clothing to receive their loot. The men carried overcoats over their arms, the sleeves sewed closed for their booty. The stolen attire was meant to clothe the escapers, and the team of thieves stole so many articles that some had to return to their cars to unload and return for more. At last Violette saw one of her team being closely observed and shouted, “My bag’s been stolen,” and the man slipped away in the confusion.

Other prisoners, not so lucky or inventive, were recaptured, many of them wounded or injured. And a few chose not to escape. One doctor, unhurt and able to flee, chose to stay behind with the wounded prisoners and to help dig out wounded still trapped beneath the rubble of Amiens Prison. Other able-bodied prisoners stayed with him.

Hiding the Escaped Prisoners

Other escapers were quickly hidden in private homes, clinics, bordellos, anyplace to get the prisoners off the street quickly. Three were sheltered in a brothel, placed, the madam said, in a room between two rooms where she would send girls to entertain visitors from German military intelligence, “a tasty Amiens jail sandwich.” The madam was an original in any case. She seldom went anywhere without her grenades, which from time to time she left under German vehicles. “Financing escapes with money the Nazis spend here,” she said, “is one of my greatest pleasures—the other is killing them.” Two other escapers seeking sanctuary—one a forger, the other a saboteur—were dressed in monks’ habits and passed across France from monastery to monastery in the company of real priests.

Many escaped prisoners were hidden in the underground vaults of a private clinic run by the father-and-son doctors Poulain, the same vaults they had used as refuge for Jews hunted by the Nazis. The vaults were hard to find, for they were concealed below the first basement … the morgue. Other escapers were hidden in plain sight, put to bed with their faces bandaged, victims of a “road accident.” Others became “expectant mothers” mounded with covers. “When are they due to deliver?” the Gestapo asked. About three o’clock in the morning, the doctor said. Why then, asked the German. Nobody knows, said the doctor; but that was when most babies were born. The Germans bought it all.

“Red Daddy”: A Costly Return Home

The bombing went so well that even the demanding Pickard was satisfied. Standing by to bore in and finish the job, 21 Squadron heard Pickard calling, “Red Daddy.” It was the call to turn and go; their extra bombs would not be needed. And then the wing’s aircraft were on their way home, roaring across France almost on the ground, chased by flak, pursued by Luftwaffe fighters. The Typhoons fended off many of the German aircraft, and the Mosquitos fought back with their formidable armament, shooting down several of the pursuing German planes. Squadron leader Ian McRichie crashlanded in a snowy pasture, partially paralyzed, his observer dead. He would survive, a wounded prisoner.

As the remaining raiders reached the English Channel, scattered and exhausted, the weather closed down again. Gray waves and thick snow showers cut visibility to almost zero. If they dived under the shelter of the clouds, visibility disappeared altogether. And then, as the Germans turned away about mid-Channel and the earth of England passed under the Mosquitos’ bellies, Hunsdon radioed landing instructions, staggering the planes’ altitude to avoid collision between tired pilots and damaged aircraft. Nobody had rested at Hunsdon or over at Embry’s headquarters. Everyone wondered and prayed. The raid had been a success, but nobody knew how many of the Mosquitos were coming home. Recon aircraft swept over Amiens and the homeward path of the raiders. Now Mosquitos were coming back, queuing up to land, but nobody knew what had happened to McRichie or Pickard.

But Dorothy Pickard knew. For Ming, Pickard’s beloved sheepdog, had collapsed, vomiting blood. A sort of supernatural bond existed between man and dog. Ming always fretted when Pickard flew, but she relaxed when her master was back on the ground, even before his wife knew Pick was back safely. She trusted Ming’s instincts. “Pick’s dead,” his wife said. And it was so. Somehow his dog’s sixth sense knew her master was gone for good.

For Pickard had stayed too long over the target, assessing the damage to the prison walls and watching his men fly clear. Turned for home, he was bounced, as the RAF put it, by two Focke-Wulf FW 190s, diving from higher altitude to offset the greater speed of the Mosquito. Pickard made a fight of it, nailing one German fighter, which ran for home. But the cannon of the second Luftwaffe aircraft ripped the tail from Pick’s aircraft and the plane smashed into the ground and burst into flame. There was very little left.

Local civilians rushed to help, using sticks to try to pull out the bodies of Pick and his longtime navigator, Flight Lieutenant Alan Bradley, but the flames were too hot and the Mosquito’s remaining ammunition began to cook off from the heat. Only later could they recover the remains of the crew, and one of them cut Pickard’s wings and ribbons from his uniform, hoping to hinder any identification by the Germans. In time, the girl who removed them sent them to his wife.

Over 250 Prisoners Saved

Pickard was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and two Distinguished Flying Crosses over an illustrious career, and many thought he should have been given the Victoria Cross for Amiens. Long after the raid, French citizens came to put flowers on the graves of Pickard and Bradley; they even went so far as to expunge the German grave markings and substitute their own.

He was gone now, and the world was much the poorer, but the success of the Amiens raid was his best memorial. The German guard force had suffered heavily, an estimated 20 killed and 70 wounded, even though the Germans publicly said they had no casualties at all. But even the Germans’ own records admitted that more than 250 prisoners had gotten away and had not been recaptured. In fact, the total was substantially greater.

Eighty-seven had died in the bombing and received a mass funeral carefully orchestrated by the French authorities. Predictably, the tame French press fulminated at the British, carefully parroting the party line that the raid was a crime. The funeral was a sad time, but even it had its bright side, for in the cortege of one of the dead, six wanted men walked piously away from the convent where they had been hidden.

Whatever the supine French press said, the French Resistance and most of the French people knew better. And 15 weeks after the strike at Amiens, the Allies came ashore in Normandy. It was the beginning of the end.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments