By John Wukovits

Stan Bowen spent the entire war in the U.S. Navy as a pharmacist’s mate, first in the operation at Tarawa, then Saipan and Tinian. His duties thus placed him in the thick of some of the Pacific’s worst combat, yet instead of fighting the Japanese, he braved bullets and bombs to tend to the wounded and dying.

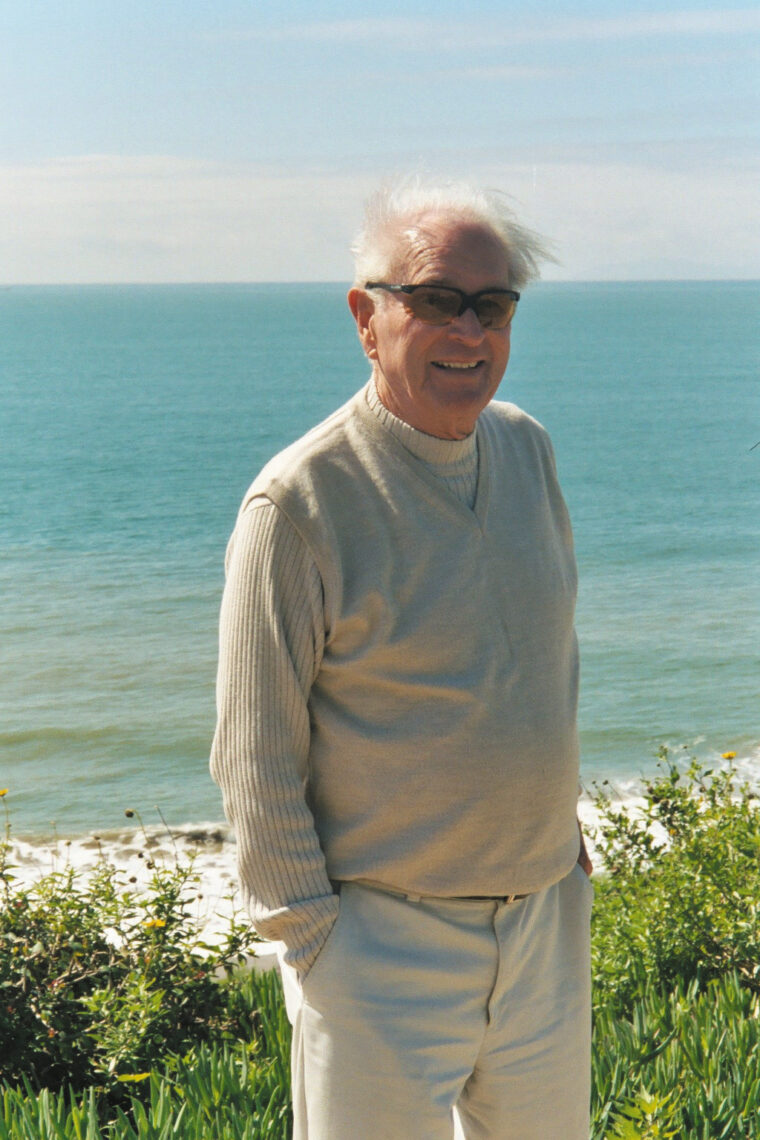

Following the war, Bowen became a successful insurance executive before retiring. From his home in Laguna Beach, Calif., Bowen took time from his thrice-weekly golf matches to reminisce about his time in the Pacific, especially during the brutal three-day slugfest at Tarawa, with author, John Wukovits. Some of the following material is included in Wukovits’s book, One Square Mile of Hell: The Battle for Tarawa, from New American Library.

Where and when were you born?

Stan Bowen: I was born January 30, 1923, in Los Angeles.

Tell us little about your childhood, your family.

SB: Dad, who worked for the Bank of America, bought this house in Beverly Hills, a fairly small house. Beverly Hills was a super place to grow up. It was a real nice town with one high school, and all the kids from wealthy families and the normal, moderate-income families got along fine. Some kids were driven to school in limousines with chauffeurs; some of us rode our bikes up to school.

You had a very close-knit family growing up?

SB: We did. We went to church my whole life, a Lutheran church.

You went to the Beverly Hills High that was on television?

SB: Yeah. We never called it that (Beverly Hills 90210). I did learn one thing—that I would never go into the entertainment business. An example. A few years ago we were at a wedding with one of my coaches from high school. He said, “You know, you were the lucky ones. When you finished working out you went on home to a family and had dinner. The rich kids would drive us nuts because they’d be hanging around the gym until all hours until we kicked them out. They didn’t have a family to go home to.” I hadn’t thought about that.

Were there any sons and daughters of celebrities at Beverly Hills High?

SB: Yeah, a few, but there was no impact. They were just one of the kids. A gal named Rhonda Fleming, a gorgeous gal. Betty White, Jackie Cooper, Bobby Breen, June Haver, Andre Previn, Blake Edwards were all there. The step-daughter of Jack Warner, Joey Paige, was there. She would invite us occasionally to her house, because she was lonely. We had to go way up a big hill, go up through a nine-hole golf course. They had a theater, a bowling room, a pool room, and when you wanted to eat, guys would come out with towels over their arms. You could have steak or turkey or chicken, whatever you wanted. We went up half a dozen times.

During those years, did world events hit you at all? Did you think much about the coming war?

SB: We knew there was a war going on [in Europe], but it didn’t affect us too much. When Pearl Harbor hit, I didn’t know where it was. That’s how important world events were. The war started when I was at San Jose State on a track scholarship. In those days, San Jose was a real big athletic school.

What do you recall about Pearl Harbor?

SB: We woke up on Sunday morning at San Jose and the radio was on and said Pearl Harbor was bombed. Honest to God, we didn’t know where Pearl Harbor was. The country got organized pretty rapidly, and we knew we’d have to go in. We didn’t want to be drafted, so my brother and [friend] Larry Kavich and I enlisted. My buddy and I, when we went to enlist, the recruiting clerk said, “You two guys must have had some first aid in school.” We did, but not much. He said he could get us a hospital apprentice first class rating, you’ll get to wear three stripes on your sleeves, you’ll get $5 more a month, and if you don’t like the medical corps you can just transfer to gunnery school or whatever you want. We thought how could we go wrong, so we signed up for it and I was a corpsman. We took it and went to boot camp.

When I got out of boot camp, they sent me to the hospital. The head nurse of the ward they put me on was a good gal. She was a lieutenant commander. She and I became close friends, and she put me in charge of wheeling the cart to pick up the food from the galley back to the ward, so that’s what I did.

How did you land in the Marines?

SB: I volunteered for the Marine Corps because of one night when I was on watch in the ward. Guys would get liberty when they were able to, and one night this guy came back, he was a Marine corporal, and it was about midnight. He turned the lights on and woke everyone. I went over and turned them off, and he went over and turned them right back on again. I said, “Knock it off! You’re waking everybody up.” He said, “The heck with you!” so we got into a big fight. I had taken boxing in high school and college and had been in my share of fights, and I just beat the—out of him. The next day my nurse friend said, “Stan, this guy is dating a Navy nurse here and she is really ticked. You broke his nose, and if I were you I’d get out of here before you’re court-martialed. You’re going to the brig, there’s no doubt about it. You don’t fight with patients.” So I went down to the headquarters and said, “I want the first draft out of this outfit.” They said they had the Marine Corps and I took it.

“We Didn’t Get Along with These Guys at all. In Fact, I Got Into a Fight With One of Them One Day.”

What about hearing news of all the early losses suffered in the Pacific?

SB: I don’t recall if it was an impression on us. All of us looked forward to going into service. It was an adventure. We were serving the country. We thought we would take care of the Japanese with no problem.

Tell us about training.

SB: The training wasn’t really that rough. The food was terrible. About half the guys were from Southern California and half from Texas and Oklahoma, and every time we came in they had that cowboy music on. We’d turn it off and put Benny Goodman on. We didn’t get along with these guys at all. In fact, I got into a fight with one of them one day.

We were at Camp Elliott for two to three months. I liked Camp Elliott. A lot of hiking and marching and shooting, physical activity. The food was a lot better. We had gas mask training. We never had to use the gas masks in the Pacific. I used it to carry extra bandages and stuff.

How did you get to the South Pacific?

SB: They took us by train to San Francisco. We stopped in Los Angeles and my parents came to see me off. Then we went to Treasure Island and were there for a few weeks. In the meantime, my brother had gotten out of boot camp as a gunner’s mate on a ship. He happened to be in San Francisco and we got together. Then we didn’t see each other until the end of the war.

They took us and put us on a boat and we went right back to San Diego. We got on this God-awful boat, I think the Western Star, that Admiral Byrd had gone to the South Pole on. The bunks were four to five deep and only about one and a half feet above your head. The food wasn’t any good.

Did you know where you were going?

SB: No. We knew we were going to the South Pacific. A dirigible followed us out for about 45 minutes watching for submarines. We went straight to New Caledonia. We didn’t stop in Hawaii. This was about June 1943.

Had you been following news of the war a little more closely now?

SB: I must have, but I don’t recall. We were all still eager to get into combat. New Caledonia was a beautiful island. It was a great place. I woke up one morning and the 2nd Raider Battalion had pulled in. They all had beards and Ka-Bar knives on their belts. One of them was a guy from Beverly High. They’d been, I guess, on the ’Canal. One night we get up and they’re all gone, to the U.S. to help form up new divisions.

I went on a boat with the 2nd Division and we headed to New Zealand. This boat was an old Dutch ship, and we hit a big storm where the waves broke over the whole ship. It was creaking like it wasn’t going to make it. We stopped at Pitcairn Island. The natives came out and half were light-skinned, descendants of Fletcher Christian and his guys. We got to New Zealand, and I was sent down to Paekakariki [a New Zealand town north of Wellington] and was assigned to the outfit I served with all the time. I was in F Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines. We got to Paekakariki. It was strictly everyday hiking, shooting, and preparing for Tarawa.

Did they train you every day, and then give you a day off each week?

SB: As I recall, we had Saturdays and Sundays off. We’d go into Wellington on the weekends, and we had to be off the streets by midnight. If you didn’t make that last train back to camp near the small town of Paekakariki, you were in big trouble.

Why was New Zealand so enjoyable?

SB: The people were real nice. Fortunately, the men were all in North Africa, so it was a free—we didn’t have any competition so to speak. I was too young to get serious, but a lot of guys got married. We’d go downtown to a bar and have a few drinks. The only date I had was to take a girl to a movie. I mainly headed to the pubs, and women weren’t allowed in the bars.

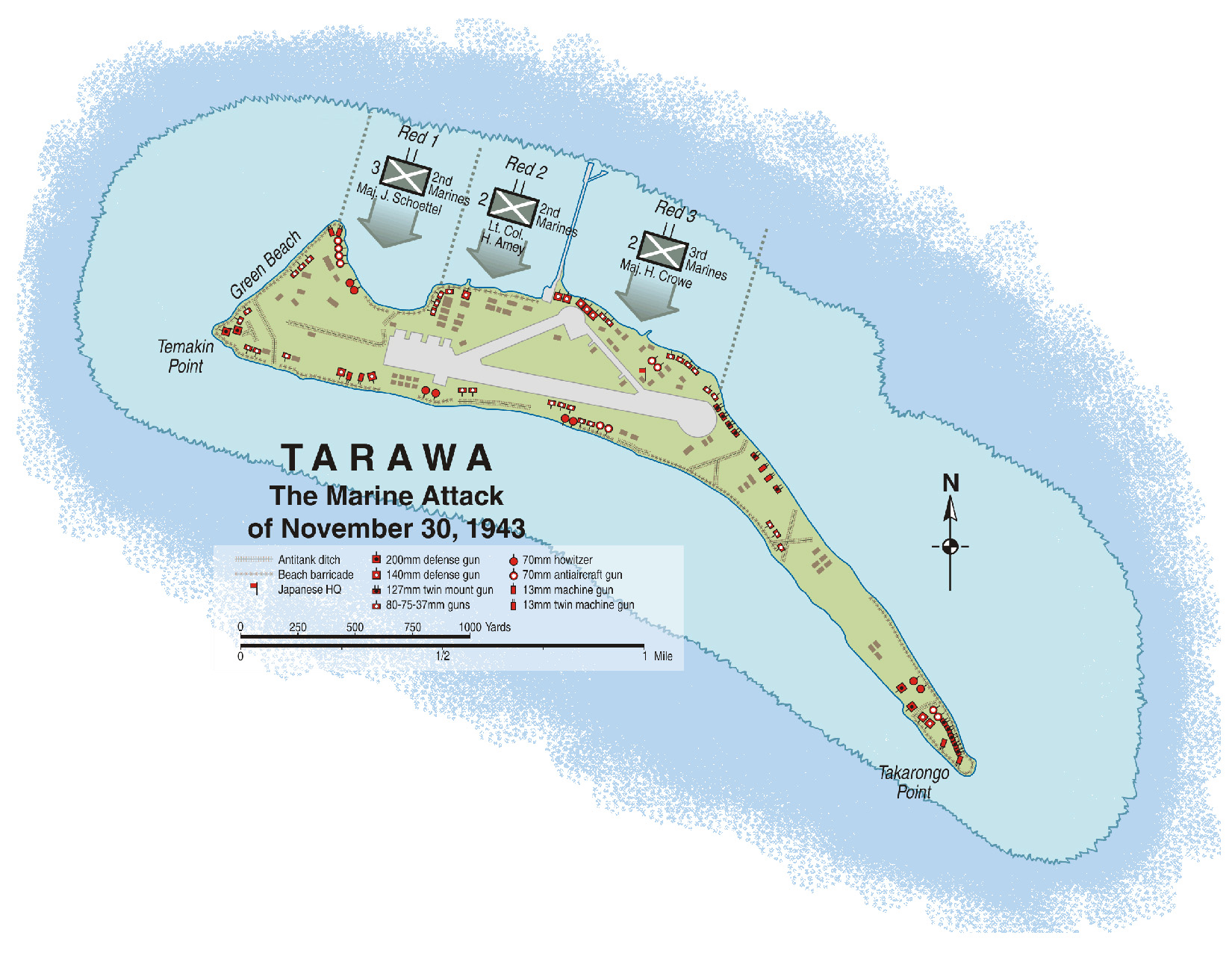

We had three to four days of maneuvers in Foxton. It was 55 miles from camp, and our major, Major Henry Crowe, a real tough Marine, got us assault landings on every operation we were on. When we joined the outfit, we had a meeting to introduce the new officers. He invited any enlisted man or officer out into the woods where he’d teach him that he was the commanding officer of the outfit. He’d beat the crap out of anyone who thought otherwise. No one ever challenged him. His executive officer, Major Chamberlin, was just the opposite! He looked like a college professor. Turned out to be a real brave guy. On Tarawa he was running all over the place.

What was the transport like from New Zealand?

SB: We went down to the docks and were tied up there for a couple of days. We had landing maneuvers in the New Hebrides. The beautiful, white sandy beach. We hit the beach in Higgins boats [landing craft needing at least three feet of water over the reef], and the natives would bring us coconuts. We were there about two days. On the ships we were jammed with guys. You couldn’t walk around hardly. Food was terrible. We had to wait in line. The quarters were real tight, bunks about four high and real close. The one above you would be right on top of you. No privacy. We had meetings about what was going to happen and where we were going. They told us that Tarawa was a tiny little place and it would be a walk in the park. It would be bombarded for a couple of days. So we didn’t expect it to be much. I was very anxious to get going. All of us wanted to kill Japs. Our company officer, Captain Barrett, told us he thought it would be an easy thing.

When you left New Zealand, did you know you were leaving for this mission and not returning?

SB: No. We didn’t really know.

“I Have No Recollection of Anyone Who was Afraid. Everyone Was Anxious to get into Action.”

When they told you it was Tarawa, what was your reaction?

SB: I had never heard of it. Up until they told us on the ship, we knew nothing of it. They had maps, paper maps laid down on the table, relief maps. Little raised portions of it to show the terrain. At Tarawa, I couldn’t wait to start killing the Japs. We hated the Japs. Just hated them. The guys from the ’Canal told us what they were like. We hated them.

Before the war did you have these bitter feelings toward the Japanese?

SB: No. We had a Japanese family in Beverly, nice guy. A friend of mine at San Jose State was Japanese. He was interned. I didn’t have any feelings before, but when I was in the service I sure did. The atrocities was what did it.

How did the other men react to learning their destination?

SB: I have no recollection of anyone who was afraid. Everyone was anxious to get into action. Except the guys who had been on the ’Canal. They never said much, but they weren’t excited like the rest of the kids were, and we were just kids then, 17-19. I was 20, a little bit older than the average Marine. The veterans were calm, and the rest were excited to get going.

On the transports before the battle, you were eager to get ashore?

SB: Absolutely.

What happened during the night before?

SB: I think I slept. I wasn’t worried at all. I honest to God didn’t think the Japs would be shooting back at us. We were really stupid. Howard Brisbane [another corpsman] was afraid and said he didn’t think he was going to make it, but I said baloney. This was a day or so before we landed. He did get killed at Tarawa. I found him after the battle. He was in the first wave. I found him on the beach. He never got even 30 yards. He had been machine gunned. He was all bloated up. He had little pointed ears, and he had a high school graduation ring so I recognized him. All those bodies lying there, bloated in the hot sun. Plus the bodies that floated in the water. The place was really a mess. The smell was horrible. I never ran into anything like that, even on Saipan, Tinian, or Okinawa.

Did you have any breakfast?

SB: I think we did. Then we went over the ship into the amtrac [amphibious tractor]. That was really spooky because you’re loaded down with your pack and your rifle, first aid kit in my case, and the ship is swaying back and forth and the amtrac is rocking. I don’t recall anyone falling into the water.

What gear did you have?

SB: The medical kit, the pack that had socks and blanket and stuff, your ammunition belt, a carbine, Ka-Bar knife, helmet. People don’t think that corpsmen carried arms, but we did. I’m not sure if they did on Guadalcanal, and I don’t think they did in Europe, but we did. They learned on Guadalcanal the Japs would pick off anyone with an insignia, like an officer or a corpsman with a Red Cross. Nobody wore any insignia. I didn’t wear an insignia. Our men knew who we were.

Did you have any last words to friends?

SB: No. I was concerned about Howard because he was really worried. Other than that, I was just looking forward to it. I was young and dumb.

I knew we would make it over the reef because I was in an amtrac, but the guys in the Higgins boats, I don’t know if they knew or not. We were on the beach, and it was terrible. We could see them [guys from Higgins boats] coming in and getting hit and there was not a damn thing we could do.

Did you feel confident before heading into Tarawa?

SB: It got to the point when we were actually going into battle, I couldn’t wait to get in, because we were going to kill Japs right and left, and I never even pictured that they’d be firing back at us. I had a feeling that we were just going in and shooting these damn Japs. I couldn’t believe it when we were landing, they were firing back at us. That startled me!

Did you have to wait in the landing craft for three to four hours?

SB: I think we did. I think we had about 15 guys in the amtrac, all in my platoon of F Company. Going in there was the pier off to the right of us, and an old ship that we got fire from. They bombed it with airplanes. That’s the first feeling of surprise they were firing at us. We had an amtrac next to us get a direct hit, and I couldn’t believe it. It blew it out of the water and killed everybody on it and arms and legs were flying through the air and I thought, “My God! They’re shooting at us!” That’s the first time I realized we were in for big trouble. We were on the reef when this happened. Then we had to go the rest of the way through all this. We were told to keep our heads down, but we didn’t. You could see the 14-inch shells going through the air.

When you were coming toward shore, what was the bombardment like?

SB: It was like a movie. Unbelievable. The 14-inch shells going through the air and hitting, and the dive-bombers hitting. We didn’t think anybody could live through that. My platoon was the extreme left flank of Beach Red 3, which meant we were the extreme left of the whole operation, and right in front of us was the big Jap command post. It had walls about three feet thick, and those 14-inch shells hit and bounced off. Unbelievable! The soldiers were Imperial Marines, and that’s why they were so damn big.

When we hit the beach, we all jumped over the side, and I had all this gear. Here in front of us was a Jap, he must have been 6’2”, stripped to the waist, swinging this saber, and guys jumping out of their amtracs. He was like 20 feet away or closer. I couldn’t believe it. Of course, he got shot right away. They were supposed to be small.

When you jumped over the side, was that tough to do?

SB: It really was. I knew this was critical, to jump with all the stuff I had. I could get hurt. The first thing I did was to move up right away to the beach, because they told us to move across the island right away. So noisy! Firing going on, hand grenades going off, airplanes strafing.

“Oh God, the Noise was Unreal! Hand Grenades, Navy Planes Dive-Bombing and Strafing Would Come Down Real Low.”

What about your first casualty?

SB: The first guy I took care of was a shocker. A friend had told me the first guy will probably be your worst, and he was right. I had worse later, but this was a shocker. Johnny Snyder and I decided we would pair up and work as a team if we found each other on the beach. The first guy was from my platoon. He was laying [sic] on his stomach but his toes were pointing skyward. We thought he had a broken leg, and we tried to pull him over, and I lifted up and my hand came through his pants. His leg was blown off. I had blood and tendons and bone and I couldn’t believe my eyes. I asked Joe if it hurt, and he said no it was numb. We applied a tourniquet to the stump, then tried to administer morphine. I stuck one in his leg but couldn’t squeeze out the morphine. I didn’t know how to use the syringe. I was unprepared for this.

Did that first casualty affect you in any way?

SB: It really did. I’d never seen anything like that in my life. But from then on, nothing bothered me. I didn’t get sick. The gut injuries were the worst, but they never bothered me. Some guys cannot stand the sight of blood, but it never bothered me.

Were you conscious of bullets hitting around you or of any noise?

SB: Oh God, the noise was unreal! Hand grenades, Navy planes dive-bombing and strafing would come down real low. There we were trying to take care of guys. You had to shout to communicate most of the time. There was nowhere to hide, really. When I hit the beach I saw these little humps in the sand about every 15 to 20 feet. They were little two-man pillboxes with machine guns, and they were the ones shooting at all the guys wading in.

You mentioned you ran around from casualty to casualty. That had to be right in the open.

SB: Right. You don’t think about the danger. I never thought I was going to get hit, and I didn’t. That first day, in the morning, I ran out to this damaged amtrac in the water about 30 yards out. Some guy had called, “Hey, Doc! There’s a guy hurt in the amtrac.” I ran out and there were four Marines hiding behind the amtrac, and they were all wounded. They said there’s a guy in the amtrac who needed help, so I jumped in the amtrac. There was a corporal from our company, and he had hung on the amtrac when it got shot so bad. He hung on the machine gun and kept firing and took a hit right in the chest. He had a hole right through him. You could practically see through him. He wanted me to stick with him, but I told him I couldn’t. There was too much going on. He died there in the amtrac.

I pulled two of these guys from behind the amtrac. I told them to dump everything and put their arms around my shoulders and we’ll head for the beach. As soon as I said, “Go!” we ran in toward the beach. Going in one of them got hit again. Then I ran back out to get the other two, which I did, and then took care of them on the beach. All these Marines were saying, “Good boy, Doc.” I was really gung ho on that damn Tarawa. I could have been hit. I remember distinctly thinking as I ran out to that thing that the little plunks of water jumping up were the Japs zeroing in, and I zig-zagged and ran up as fast as I could.

I got the commendation for doing that. The doctor on the ship later called me in and asked, “Did you run out to an amtrac and pick up some guys?” I said yeah. He said, “I heard about that, so I’m putting you in for a Silver Star.” That dumbfounded me because I figured I was getting in there to get bawled out for something. I got a commendation.

When you went out to get those Marines, you didn’t think of the dangers?

SB: No. I just did it. You don’t think in a situation like that. You just do it. I knew damn well they were shooting at me.

Were the men you were treating quiet as you treated them, or were they screaming, or what?

SB: There was no panic that I recall. The only fellow I can remember in panic was on Tinian. He was yelling for his mother.

Did any of the Marines you tended say anything to you?

SB: They’d say thank you. “Thanks Doc.” Some got back up and resumed fighting. Most of them did. I was patching guys up all over.

Did you at any time think you were going to die?

SB: No. Never gave it a thought. I think for a guy to have that feeling would be a dangerous thing. If you’re afraid, you can’t do what you’ve gotta do.

Was the island always smoke-filled and dusty?

SB: Yep, it was. The shells produced a lot of smoke, and the noise was unreal, and it was constant from shooting and hand grenades and all. My ears always have rung since then.

Did anyone freeze with fear?

SB: Not that I saw. One guy had battle fatigue or whatever you call it, shaking and crying and throwing up. I guess he was just a wreck. After the battle they sent him back to the rear. Some people can’t handle the noise and the shooting and the fear. There must have been others.

We had one guy from our outfit, from Los Angeles. When we hit the beach on Tarawa he fell apart. He couldn’t do anything. He was the only one I knew who couldn’t. He later begged the doctor to let him have another chance, and he did the same thing at Saipan. Nobody felt anything adverse against him. We just realized that some guys just can’t do it.

Corpsmen don’t get a lot of play in books about combat.

SB: I’ll tell you, in the Marine Corps, the Marines that were in our combat outfits, they really liked the corpsmen. We were buddies. I’ve discovered since that a lot of Marines who weren’t in combat, they don’t have respect at all. They say you’re not a Marine. But every hike they went on, we went on. We lived right with them. We shot on the rifle range with them. We were just part of the group. Then once the fighting began, our job was to take care of them, and they took care of us.

Did you shoot your weapon?

SB: I did. I got a guy. I walked back to the aid station, about 200 yards down the beach, to get more supplies. I was sitting down talking to a friend of mine, and I was leaned up against the coconut wall. All of a sudden he gets hit right in the middle of his eyes. He gets this surprised look on his face, and he falls over dead. I couldn’t believe it. I wheeled around and up in the tree I thought I saw something. I fired up into this coconut tree and a rifle fell out, so I’m pretty sure that was my first Jap. The tree was about 20 yards away. There’s others, but my job wasn’t to kill Japs.

Major Crowe just reamed me out. “If you want to kill someone, get over the log fence! You’re drawing attention here!”

“I Recall Two Guys Who Jumped on Hand Grenades to Save Others.”

Did you fire your rifle after that?

SB: We couldn’t move forward, so we went back to the sea wall and kept throwing hand grenades back and forth. I threw them and fired my weapon whenever I had a lull from treating guys. As far as treating, all we could do was sprinkle the sulfa powder and bandage it up somehow, and use a morphine syrette if he was really bad. That first guy was in 30 to 50 yards at most when I treated him. That first day we hung by the beach by the sea wall. We couldn’t move. We saw all these guys wading in and getting slaughtered, and we knew we were in trouble.

What about that first night?

SB: All night we carried guys out to the pier and carried water and ammunition back. It was so damn hot everybody needed water. I still carried my rifle.

That first night, did you expect a big counterattack?

SB: We did. For some reason they didn’t, and that’s when they blew it because they had us. I got no rest that first night. We had so many wounded guys and we had to get them off. We had K and C rations, and we must have eaten, but I don’t recall doing it.

Did the actions of any other men surprise you?

SB: Yeah, they did. Guys were doing things. I recall two guys who jumped on hand grenades to save others. They probably saved maybe one guy, their buddy, and they got nothing, no medal, for that.

What really impressed me was the strength of the Marines. They didn’t give up. They hung in there. It made me feel more a Marine than a Navy guy. I still feel pride in the Marine Corps and consider myself a Marine and always will.

In those final days, does anything stand out?

SB: When I ran out to get those guys in the amtrac. When we started moving in on the third day, my buddy John Snyder got hit near the command post. I recall guys going in that command post with flamethrowers. Then, when we moved down toward the end of the island when it was over, I started thinking of Howard Brisbane, so I went looking for him. He had landed not too far from where I landed. That’s the most vivid part.

Out of a 24-hour segment, how many hours would you be tending the wounded?

SB: We were awake all day long, and two nights we spent carrying wounded out at the pier. It was so damn hot! Sunburn was a major problem. My lower lip was just split from being burned. I suppose it was bleeding, too. A lot of guys were sunburned, and you’re so dirty from dust and dirt and grime, it acted like sunscreen I guess.

Do all the days blend together, or can you separate them into the three days?

SB: It kind of blends together. The first day is very vivid, much more so than the second and third day. We were pretty much stuck on the left flank. Each day I’d work my way down to the battalion aid station about 200 yards away on the beach. Funny how in a battle like that, nobody knows what’s going on on the other end.

Tarawa was my first battle, and most vivid. It was the worst because it was concentrated into three days instead of a month or so. We could never let our guard down. We had so little sleep. You’re so tired all the time. God we were exhausted! We were under fire.

When did you first start to believe you were going to win?

SB: The last day, when we finally went over the sea wall. We knew we couldn’t move on our beach, and we didn’t know what was going on elsewhere. When the 6th Marines started moving forward, we started moving up.

How about leaving?

SB: I don’t recall seeing them raise the flag, or the plane landing on the airstrip. They must have gotten us off pretty quick. They took us, I guess, on amtracs, to the next island. We stayed a day or two there and cleaned up ourselves and uniforms, by going swimming. We didn’t have any soap. Then we went to Hawaii.

“A Guy Yelled at Me to Check a Guy in the Tent Next to it, and He’d Been Hit in the Jugular Vein and He was Dead.”

You mentioned you were never hit in combat. Were you ever injured?

SB: I did get hit in Hawaii. After Tarawa. They landed us and there was no camp, no nothing, just a blanket and a toothbrush. You’d think they’d have something waiting for us.

I was in a tent with four or five other corpsmen and was reading a letter from my brother at a little table we had built, and all of a sudden there was an explosion that knocked me back. I felt my knee hit underneath the table, and I didn’t think anything about it. We ran out, and here these guys across the street from us were pouring out of their tent. Turned out a corporal who had been on the ’Canal had picked up a 37mm dud, put it in his pack, brought it back, got into his tent, threw his pack off, and hit it on a case of Coke—everybody was addicted to Coke—and it exploded. It broke his leg, but it blew the feet off two to three other kids who had just come over from the States. These guys were running out and there was blood all over the place, so we grabbed our first aid kits and took care of them. A guy yelled at me to check a guy in the tent next to it, and he’d been hit in the jugular vein and he was dead. He had been the best friend of this corporal.

We got back in the tent, and one of my buddies said, “My God, look at your leg, Stan!” I looked down and my leg was covered in blood, and there was a hole in the tent where a piece of shrapnel had hit a 2 by 4, then hit the bottom of the table, went down through the deck, and then hit just below my knee joint. When the doctor looked at it, he said he had to send me over to the hospital, and he said, “Now, they’re gonna want to cut you open. Don’t let ’em do it. I predict the shrapnel won’t bother you.” He was right. The shrapnel bothered me for a year or so, and that’s it. It’s still in me.

Did you have nightmares?

SB: Marge [his wife] says for a long time I was moaning and groaning in my sleep, but I don’t recall. I’m a more easy going type of guy, so serious things don’t seem to bother me. I had a smooth transition. I got married, and I started school and got right back in the swing of things.

Did you have any health problems because of Tarawa?

SB: Not really. I got some shrapnel in my legs from Hawaii, and some dengue fever. Thank God I never got malaria. The shrapnel in my leg, between you and me, is a piece of cake. It’s nothing.

Have you men been forgotten by the country?

SB: I think we were for years and years, but recently the people have rediscovered guys from World War II, Vietnam, and Korea.

Why should people remember Tarawa?

SB: The determination of the young guys, kids. They never gave up. Only one, a corpsman, had battle fatigue.

Do you consider yourself a hero?

SB: No!

Why not?

SB: I did what anybody else would do. They’re doing it today in Iraq. Any of my friends would have done what I did. The only outstanding thing I did was going out and getting those Marines, and I knew that was dangerous. But that was my job to do. I was a corpsman. If a guy’s hurt, you’ve got to go get him. That was your job.

Without in any way of diminishing the valor of our troops, many military experts question the wisdom of the invasion. Its airfield was easily destroyed and it had no way of getting troops to any of the other Japanese held areas. While the plan to attack Japan via island hopping was quite valid, not as much detail as to which islands were strategically necessary went into the process.