By Edward F. Chen

In October 1949, the government of the Republic of China faced the greatest crisis in its history. After four years of bloody civil war, Nationalist forces headed by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek were in full retreat, as the Communist forces under Mao Zedong swept inexorably south. By the time Mao declared the Peoples Republic of China in Beijing on October 1, the Communists had conquered most of China, including all the major cities. It was only a matter of time before they overran the last remaining Nationalist-held enclaves in the northwestern and southeastern corners of the mainland.

To ensure the survival of his regime, Chiang Kai-shek withdrew his forces to the island of Taiwan, preparing it as a last-ditch bastion. The Nationalists also fortified several strategic island groups just off China’s southeastern coast, including Hainan, Zhoushan, Matsu and Kinmen, better known in the West as Quemoy. The Kinmen Islands, a group including two small islands and 13 islets, are located about six miles off the coast of mainland China, immediately opposite the port city of Xiamen (also known as Amoy), astride the entrance to Xiamen Bay. The larger of the two islands, called Greater Kinmen or simply Kinmen, a dumbbell-shaped land mass about 100 squares miles in size, was home to about 30,000 people in 1949. The eastern half of the island is mountainous, while the western half is generally flat and surrounded by miles of beaches suitable for amphibious landings.

The “Golden Gate”

In Chinese, “Kinmen” means “Golden Gate,” an appropriate name for the islands. Xiamen was the closest major mainland port to Taiwan, about 100 miles away, but Kinmen was the key to the region, the gateway to Xiamen Bay and ultimately to Taiwan itself. As long as the Nationalists held Kinmen, they could bottle up the port and deny its use by the Communists in any attempted invasion of Taiwan. If the Nationalists lost Kinmen, not only would Taiwan be immediately threatened, but the political stability of the demoralized regime as a whole would be jeopardized.

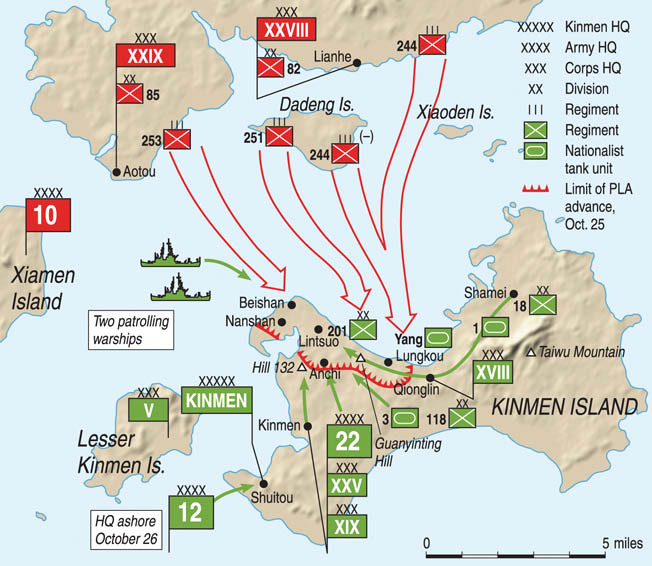

In early October 1949, the Nationalist defense of the Xiamen region fell under the Fuzhou Pacification Command. Its two armies were headed by General T’ang En-po, a veteran of the wars against the Japanese and the Communists. The 8th Army, under the loyal but mediocre Lt. Gen. Liu Ju-ming, defended Zhangzhou and Xiamen Island with six divisions numbering some 30,000 men. The 22nd Army, led by the more capable Lt. Gen. Li Liang-jung, garrisoned the Kinmen islands, with 17,000 men in three understrength infantry divisions, plus supporting units and a light tank battalion stationed on Greater Kinmen. Another 3,000 men were posted on Lesser Kinmen.

As the Communists advanced relentlessly through Fujian and closed in on Xiamen, Chiang Kai-shek ordered the coastal islands to be reinforced at the expense of the remaining mainland territory. The rebuilt Nationalist 12th Army, under Lt. Gen. Hu Lien, was directed to transfer its headquarters and two of its three corps, totaling 40,000 men, from the Chaozhou-Shantou region of Guangdong province to the Kinmen Islands. XVIII Corps, under Maj. Gen. Kao K’uei-yuan, reached Kinmen with three divisions on October 9. Days later, the 19th Corps under Maj. Gen. Liu Yun-han followed suit, arriving off Kinmen on the 23rd to begin unloading its troops on the southernmost beaches. The Chinese Air Force patrolled the southeastern coastline of the mainland, ready to sink any ships or civilian vessels that could be put to use for amphibious operations.

“Washing Taiwan in Blood”

During the summer and autumn of 1949, the 3rd Field Army of the Chinese Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) swept south from the Yangzi River through the coastal provinces. Leading the advance into Fujian was the PLA 10th Army, comprised of the XXIX and XXXI Corps, with nine divisions totaling 158,000 battle-hardened troops under Army Commander Ye Fei. By mid-October, the 10th Army had seized most of the major cities in Fujian and was poised to seize Xiamen and the islands in the bay as the first step toward “washing Taiwan in blood,” as the Communist rhetoric of the time all to accurately warned.

Due to the terrain in which it operated, the 10th Army became the PLA’s specialist in amphibious warfare. With no experience in that field, Ye Fei’s subordinates had to adapt their well-practiced techniques for crossing rivers and other water obstacles and apply them to the seizure of offshore islands. Since the PLA was still predominantly a light-infantry force with few naval or air assets, the Communists were forced to improvise. Their operations were constrained by the number of local civilian vessels and fishing boats they could impress into service.

Ye Fei’s 10th Army began its coastal campaign in mid-September with the seizure of Pingtan Island off the coast near Fuzhou. Five regiments crossed the bay in hundreds of commandeered fishing vessels and assaulted the island in the face of an oncoming typhoon, managing to overwhelm the Nationalist garrison of 7,000 men with little effort. Despite the precarious vulnerability of their primitive mode of transport to local weather and sea conditions, the Communists continued to prevail because of consistently ineffectual Nationalist resistance. On October 15, Ye Fei’s XXIX and XXXI Corps took Zhangzhou and assaulted the heavily defended island of Xiamen. Two days later the island and its vital port fell after brief but heavy fighting. Of the defending Nationalist 8th Army, only its commander and 4,000 troops managed to escape. When the nearby small islands of Dadeng and Xiaodeng were also taken, Ye Fei and his subordinates were confident that the Kinmen Islands would fall just as easily.

A Risky Amphibious Landing

The man assigned the mission of taking Kinmen, XXVIII Corps Deputy Commander Xiao Feng, was not so optimistic. His corps had encountered great difficulties in finding enough fishing vessels and local crews to form a makeshift transport fleet, which finally amounted to 320 mostly sail-powered wooden vessels and boats of all sizes. In the final plan, three regiments with nearly 9,000 crack troops would cross Xiamen Bay at night and land on the beaches between Guningtou and Lungkou. The first wave force would seize the coastal high ground and establish a defensible beachhead before advancing south. Meanwhile, it was hoped that enough of the transport vessels would survive to return and pick up additional troops from the XXVIII and XXIX Corps in follow-on waves. The 10th Army’s 85 available artillery pieces, including both 75mm and 105mm howitzers, would provide fire support. It was an extremely risky plan. After much delay and several postponements, the amphibious assault was finally scheduled for the night of October 24.

In previous campaigns of the Chinese Civil War, the Communists had prevailed in large part due to the widespread information they obtained through an elaborate network of spies and sympathizers in the Nationalist ranks. In this case, however, the network did not extend to Kinmen, forcing PLA commanders to rely on intercepted enemy radio transmissions. Although they were aware that Hu Lien’s Nationalist 12th Army might be sent to Kinmen, the Communists had only an inkling of its current whereabouts, ignoring signs that some 12th Army units were already on the island. Determined to win the race against time and contemptuous of the enemy, Ye Fei urged his subordinates to rush preparations and invade as soon as possible. His army had consistently vanquished nominally superior Nationalist forces, and he had little reason to believe that this time would be any different. But in this case the Communists completely underestimated their enemy.

On Kinmen, the most likely invasion sites were situated along the 10 miles of beaches on the northwest coast from Guningtou in the west to Lungkou near the center. These villages were defended by the two infantry regiments of Maj. Gen. Cheng Kuo’s elite but understrength 201st Ch’ing-nian-chün, or Youth Army, Division. In reserve nearby were Colonel Li Shu-lan’s 118th Division of the 12th Army’s XVIII Corps and the 1st Tank Battalion (1st Battalion, 3rd Tank Regiment) commanded by Lt. Col. Ch’en Chen-wei, with 22 American-built M5A1 “Stuart” light tanks organized into two tank companies.

Veteran Tankers on Kinmen

The Chinese Nationalist Army’s 1st Tank Battalion drew its lineage to the First Provisional Tank Group (Chinese-American), formed in Ramgarh, India, in 1943. During 1944-1945, they had provided armored support for joint Chinese-American forces advancing through northern Burma to clear the Ledo Road land supply route to China. After the war, the Chinese personnel of the Tank Group formed the core of the Nationalist Army’s armored force, which was eventually expanded to three tank regiments and equipped with a mix of American, Japanese, and older foreign-built vehicles for use in the civil war against the Chinese Communists.

Unlike most of the defending Nationalist troops, the tank crews were veterans, survivors of many campaigns and well-trained in providing infantry support. However, throughout the civil war the great combat potential of the armored force was squandered by bad generalship and supply problems. Nationalist tankers were rarely able to deliver significant blows against the Communists, even though the PLA lacked tanks or antitank weapons in significant numbers. In December 1948, during the decisive Huai-Hai Campaign in which the Nationalists lost five armies and over half a million troops, the tankers had been partly surrounded near the village of Shuangduiji in Anhui Province. They had barely managed to escape in a desperate breakout led by then-deputy Army commander Hu Lien, but had lost all their vehicles during the retreat. The men of the 1st Tank Battalion were withdrawn to Taiwan for refitting and retraining. They spent the next spring and summer getting replacement tanks operational before they were redeployed to Kinmen in September 1949 as one of the Nationalist Army’s few remaining combat-ready tank units.

The afternoon of October 24 found the Nationalist garrison on Kinmen engaged in anti-invasion exercises. Among the participants were the three tanks of 1st Platoon, 3rd Tank Company, led by 1st Lieutenant Yang Chan. Just before dusk, the platoon was about to return to the company bivouac at Tingpao when Yang’s own tank, No. 66, became stuck in a soft patch of sand on the beach north of Lungkou. Repeated attempts to free the tank were to no avail. Yang ordered one of the other Stuarts to hitch a towing cable and drag his tank out of the sand, but the second tank threw a track. The tank crews repaired the track and repeated the process several times, but No. 66 still remained stuck. Finally, Yang headed to Tingpao to get help. He returned to the repair site at 3 am, bringing along an unditching ramp and some leftover rations. While the men ate, they discussed how to go about freeing the stranded tank.

“All Vehicles on Alert!”

Suddenly the coast was lit up by three signal flares that pierced the moonless night. Communist artillery batteries on the opposite shore opened fire on Kinmen, and a barrage of shells came down near the tank platoon, scattering shrapnel through the air. After 10 minutes of shelling the fire lifted, and the tankers could hear the ominous splashing of men wading ashore. At the shoreline to their front, some 3,000 enemy troops of the PLA 244th Regiment, 82nd Division, led by Regiment Commander Xing Yongsheng, began jumping out of dozens of wooden vessels and struggling through the surf toward the beach.

“All vehicles on alert!” Yang bellowed over the radio set. “Assemble around Tank Number 66 and face the shoreline, in platoon line-abreast formation.” After the other two Stuart tanks lined up around him, he ordered the entire platoon to open fire. Wooden boats burst into flames as the tanks and Youth Army troops in nearby bunkers unleashed the first shots of the battle. For the next hour they kept up a storm of fire, mowing down dozens of Communist troops charging up the beach and fighting off repeated assaults with grenades or demolition charges. In a curious twist of fate, a vehicle breakdown had placed the tank platoon in exactly the right spot to bar PLA assault troops from their objective: the town of Qionglin at the center of the island, the key high ground of Taiwu Mountain. If the Communists seized the area, they could cut the island defenses in two.

As the Kinmen defenders went on alert, General T’ang En-po ordered counterinvasion plans put into effect. In turn, the 22nd Army commander, Lt. Gen. Li Liang-jung, ordered Ch’en to send the rest of Captain Chou Ming-ch’in’s 3rd Tank Company into the attack, even if they had to grope their way through the darkness. The four available tanks of Chou’s 3rd Company and troops of the Nationalist 118th Division set off into the night, clashing with PLA troops that had reached Guanyinting Hill. One Stuart was struck by a glancing blow from a PLA bazooka round, knocking out one of its two engines. The crippled tank was able to hobble back to base.

In the face of stiff enemy resistance, Chou summoned Yang Chan’s 1st Platoon into the fray. Yang complied and led the two mobile Stuarts of his platoon into the attack. Meanwhile, the crew of immobilized tank No. 66 and some 200 Youth Army troops held firm, engaging the Communists in close-quarters combat. Since tank No. 66 faced inland, driver Tseng Shao-lin and other crew members set up the tank’s bow machine gun on a sand berm and engaged the PLA troops in an intense firefight. During the battle, a hail of bullets killed Tseng—the first casualty sustained by the tank unit.

PLA Trapped on the Beach

Farther to the west, the PLA 251st Regiment, led by Liu Tianxiang, and the 253rd Regiment, led by Xu Bo, had landed in the sector between Huwei and Guningtou. The transport groups, scattered by the winds and waves, had suffered heavy losses during their journey across the bay. Nevertheless, they were able to overwhelm the forward defensive positions of the 201st Youth Army Division and push inland, taking the town of Guningtou. In the west, PLA troops reached as far south as Hill 132 before they were forced back by Nationalist reinforcements. The three PLA regimental assault groups were forced to operate independently. No division-level or senior command staff was present to coordinate their movements. Confusion reigned in the beachhead and units became completely disorganized.

Crucially, the Communists had failed to accurately determine local tidal conditions around Kinmen. To achieve surprise and minimize exposure to enemy fire during the assault, Xiao Feng had scheduled the landings at high tide. A few hours later the tides quickly receded before the PLA could organize their improvised transports to cast off. All of their surviving vessels were now stranded on the beach and battered by intense Nationalist fire. Not only would there be no reinforcements, but the first wave troops were trapped on the island without even the prospect of escape.

“… the Enemy Must Number Over Ten Thousand!”

At the same time the 3rd Tank Company was fighting for its life on the beaches north of Lungkou, its sister unit, the 1st Tank Company, was bivouacked at Shamei to the northeast. Deputy platoon commander 2nd Lieutenant Mu Chü-liang was the on-duty watch officer when the first enemy artillery shells began falling. Mu alerted his company commander, Captain Hu K’e-hua, and the crews of seven available tanks were soon ready to roll. They remained on standby until dawn, when Hu finally received orders to drive to Qionglin, where they were to join up with infantry from the 118th Division. When they reached the village, one tank dropped out from engine trouble, and no friendly infantry showed up to accompany them, so Hu decided to march to the sounds of the battle. Advancing along the coastal road, the tankers reached the enemy beachhead at 6:30 am, where they spotted over 100 stranded wooden vessels. Hu reported to his superiors, “With that many boats over there, I think the enemy must number over ten thousand!”

After receiving orders to destroy the enemy wherever they were encountered, Hu led the 1st Tank Company down the enemy-held beaches. Meeting little resistance, the six Stuart tanks blasted away at any enemy troops they encountered. Since they lacked infantry escort, the tankers advanced cautiously at first, keeping their distance and plowing forward only after they had thoroughly shot up enemy positions.

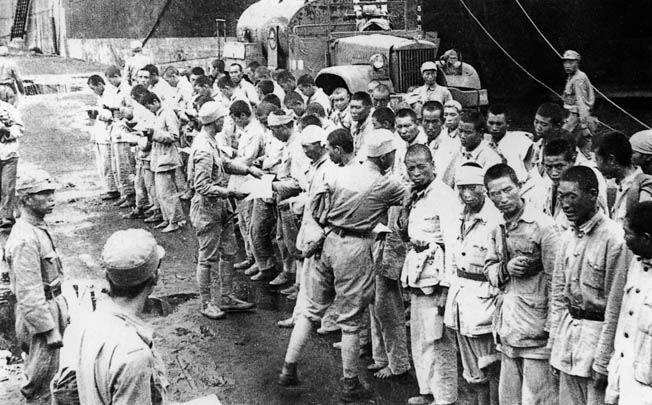

Mu and the crew of tank No. 22 fired away without pause at enemy troops that seemed to be all around them. In the process, the tank’s worn-out batteries gave out, and at 6:50 the vehicle lurched to a halt, losing all electrical power—even for the radio. With a Thompson submachine gun and signal flags in hand, Mu opened the hatch to contact the other tanks for assistance. He saw dozens of exhausted enemy troops huddled in a nearby trench, offering no resistance. Brandishing his weapon, Mu yelled at the nearby enemy troops to lay down their weapons and head toward the rear. Nearly 80 Communists surrendered and were herded off to Qionglin. While another tank helped recharge No. 22’s batteries, Mu found out why there had been surprisingly little enemy fire. Upon inspecting the discarded enemy weapons, he discovered that they were inoperable due to exposure to seawater, sand, and grit.

At around 7 am, Hu led four tanks to the shoreline and blasted away at the grounded transport fleet. High-explosive shells set the wooden vessels ablaze, incinerating enemy wounded who had taken refuge inside them. The tankers continued north to Guanyinting, where they encountered hundreds of PLA troops hiding in shallow foxholes or abandoned Nationalist trenches. The Nationalist tanks bounded forward, maneuvering to enfilade the enemy positions, and unleashed a torrent of cannon and machine-gun fire, scattering hundreds of steel fragments of canister through the ranks of the enemy. Unable to bring to bear any of their few surviving bazooka teams, PLA troopers from the 244th and 251st Regiments could only respond with small-arms fire or ineffectual grenade attacks. Soon, they were overwhelmed by fire and forced to retreat. In the process, the headquarters of the 244th Regiment was overrun and regimental commander Xing Yongsheng was severely wounded and captured.

2,000 Killed, 2,400 Captured

An hour later Nationalist infantry of the 118th Division finally caught up with the tanks, taking hundreds of prisoners. The four Stuart tanks continued their westward advance, blasting away at enemy positions and stranded wooden vessels. By 11:30, the 1st Tank Company had expended most of its fuel and ammunition and was forced to return to Shamei to replenish supplies. Other troops from the Nationalist 18th Division arrived in strength to consolidate the tankers’ gains. Meanwhile, to the south, the 3rd Tank Company drove westward past Guanyinting Hill and engaged Communist forces at Anchi along with troops of the 118th Division.

In the space of a few hours, the Nationalists captured some 2,400 prisoners and liberated several hundred Nationalist Youth Army troops who had themselves been taken prisoner by the Communists during the initial rush. More than 2,000 enemy dead lay scattered among wrecked and burning transports on the beaches between Lungkou and Guningtou. Decades later, Mu Chü-liang would write, “In the dozens of battles that I have fought I had never witnessed a spectacle as terrible as this.”

Now the Nationalists attacked the Communist beachhead at Guningtou. Units from four divisions of the 12th Army, some of which had just arrived on the island, advanced against the key village of Lintsuo. There, the veteran PLA troops had consolidated their defenses, digging in among the brick houses of the village. Well-sited machine guns and mortars exacted a frightful toll among the Nationalist infantry, killing a regimental colonel and a battalion commander. The inexperienced infantry had never fought alongside tanks, and coordination was poor. Yet the Nationalists stubbornly repeated their attacks. The tankers again proved their worth, acting as mobile pillboxes and eliminating enemy strongpoints.

Crushing the Remaining PLA Resistance

By the end of October 25, the Nationalist forces had sealed off Guningtou and wrecked the makeshift Communist transport fleet stranded on the beaches. The PLA invasion force had lost more than half its strength, and was running low on ammunition and supplies. The Communists still held the high ground and were determined to hold out, in the hope that reinforcements would arrive. They were encouraged when XXVIII Corps managed to slip another 300 men ashore that night, led by 246th Regiment commander Sun Yunxiu.

The following day, the Nationalist tankers resumed their infantry support role, spearheading repeated infantry attacks against the Communist defensive perimeter around Guningtou. It was no easy task. The PLA troops had become proficient at hiding in their positions, letting the tanks roll past before emerging to unleash devastating fire on the infantry following behind. Attack after attack was broken up. Bloody street fighting ensued in Lintsuo, and its shattered houses and buildings exchanged hands several times. Eventually, the sheer weight of numbers prevailed; by nightfall the Nationalists had recaptured the village. With no prospect of additional Communist reinforcements, the outcome of the battle was now inevitable.

Because of Kinmen’s critical importance to the survival of the Nationalist regime, a number of senior government leaders descended on the small island to see for themselves that the situation had stabilized. Chiang Ching-kuo, the Nationalist leader’s eldest son and leading troubleshooter, flew to Kinmen to pay a special visit to the 1st Tank Battalion command post at Qionglin to congratulate the tankers and offer rewards. The popular 12th Army commander, Lt. Gen. Hu Lien, also arrived at Qionglin that afternoon to visit the tankers.

On the morning of the 27th, the Nationalists began their final effort to clear out the remaining Communist positions at Guningtou, with simultaneous thrusts from the south and east. By the afternoon, the Nationalists reoccupied Guningtou. Organized resistance ended with the capture of 900 remaining PLA troops who had fled to the beaches and bluffs to the north. Over the next few weeks, dozens of PLA stragglers were rounded up around the island. PLA regimental commanders Xing, Liu, and Xu were captured, imprisoned in Taiwan, and later executed; 246th Regiment commander Sun Yunxiu took his own life. In all, 5,175 Communists were taken prisoner out of a total of 9,086 men who had embarked on the invasion. Some 3,000 of these prisoners were repatriated back to the mainland in 1950 after they refused to go over to the Nationalist side.

Kinmen and Matsu: Securing Taiwan From the Mainland

The battle for Kinmen proved to be a watershed event in the Chinese Civil War. For Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalists, the victory secured their last-ditch bastion on Taiwan from Communist invasion and invigorated their cause after a succession of defeats during the previous year. Despite the fact that their enemy had rashly miscalculated by launching an amphibious assault against a numerically superior enemy enjoying armor, air, and naval support, victory came at a heavy price. During the 56 hours of what the Nationalists would later call “the Great Victory at Guningtou,” they lost 1,267 men dead and 1,982 wounded in the vicious close-quarters combat. The tankers, who were instrumental in achieving the victory, lost two dead and seven wounded. Their efforts were recognized on November 5, when the new Kinmen garrison commander, Hu Lien, bestowed upon the men of the 1st Battalion, 3rd Tank Regiment, the honorific nickname, “the Bears of Kinmen.”

The defeat at Kinmen was a profound shock to Mao Zedong and his military commanders. Recognizing how overconfidence had led to the disaster, the Communists took a more systematic approach toward the conduct of future amphibious operations. Over the next few years, the PLA refined its techniques and succeeded in driving the Nationalists from their remaining coastal island outposts. However, the inability to take Kinmen and Matsu ruled out any invasion attempt against Taiwan proper.

Transformed into impregnable island fortresses, Kinmen and Matsu played prominent roles on the front lines of the Cold War, with Kinmen subjected to punishing artillery bombardments during the 1950s as the Communists tried but failed to drive out the Nationalist garrisons. In 1958, the bombardment of Kinmen nearly sparked a nuclear conflict between the Chinese Communists and the United States, and the issue was hotly discussed during the famous Kennedy-Nixon presidential election debates of 1960. Although tensions across the Taiwan Straits have lessened to such an extent that both islands have become popular tourist attractions, the reduced garrisons of Kinmen and Matsu still remain symbolically on guard against possible threats from the Communist mainland.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments