By Michael D. Hull

Brave, urbane, and complex, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto was Japan’s greatest naval strategist and the architect of one of the most stunning achievements in the history of modern warfare.

Fluent in English, he studied in the United States and claimed many American friends before he became one of their deadly enemies. A solid and widely respected man, he argued passionately for peace in the 1930s while fascism spread in Europe and a fanatical militarist faction in Tokyo was calling for aggressive expansion in the Far East. Yet Yamamoto was a patriot to the bone, and when ordered to fight, he waged war with a vengeance.

Yamamoto’s Pearl Harbor Blueprints: Inspiration From the Battle of Taranto

As war approached, he was initially uneasy and warned his countrymen of the likely consequences of provoking the West. Having studied briefly at Harvard University and spent two years in Washington as a naval attaché, he admired America and was aware of its industrial strength and potential military power.

“Japan cannot beat America,” Yamamoto told a group of school children in 1940. “Therefore, Japan should not fight America.” He played no part in the militarists’ decision for war, but, when the decision was made, he quickly summoned his strategic wisdom and was adamant on one point: the only course open to Japan in gaining control of the Pacific area was to destroy the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

When the Navy General Staff unanimously opposed his plan, Yamamoto declared, “The U.S. Fleet … is a dagger pointed at our throat. Should war be declared, the length and breadth of our southern operations would be exposed to serious threat on its flank.” Only when the commander in chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet threatened to resign and retire if his plan was not approved did the General Staff concede. “If he has that much confidence, it is better to let Yamamoto go ahead,” said the naval chief of staff.

Believing that a preemptive strike to cripple the U.S. Navy at the outset was Japan’s only hope against such a powerful opponent, Admiral Yamamoto started planning the Pearl Harbor assault in early 1940. But he was not optimistic. “If you tell me that it is necessary that we fight,” he told the bellicose Tokyo high command in September 1940, “then in the first six months to a year of war against the United States and England, I will run wild, and I will show you an uninterrupted succession of victories; but I must tell you that, should the war be prolonged for two or three years, I have no confidence in our ultimate victory.”

Yamamoto’s Pearl Harbor blueprint was influenced by the spectacular destruction of the Italian Fleet at Taranto on November 11, 1940, by Fairey Swordfish biplane torpedo bombers of the British Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm. An earlier inspiration, according to many experts, was a 1925 book, The Great Pacific War, by Hector C. Bywater, the naval correspondent for the London Daily Telegraph. With uncanny foresight, the novel described a Japanese surprise attack on the U.S. Asiatic Fleet at Pearl Harbor and simultaneous assaults on Guam and landings in the Philippines.

Yamamoto realized that the Hawaii operation was dangerous but that the odds were too good not to take. “If we fail, we had better give up the war,” he said fatalistically. As it turned out, the carrier-plane attack early on the morning of Sunday, December 7, 1941, executed by heavy-set, gray-haired Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s strike force, achieved strategic and tactical surprise. It caught Admiral Husband E. Kimmel’s anchored Pacific Fleet napping and thrust America rudely into World War II.

“The Rise or Fall of Our Empire Now Hinges on This Battle”

Admiral Yamamoto’s final message to his carrier crews and pilots had echoed the rallying cry of the commander of the victorious Japanese fleet at the decisive Battle of Tsushima in 1905: “The rise or fall of our empire now hinges on this battle.”

On the fateful morning, two waves of torpedo bombers, dive bombers, high-altitude bombers, and fighters from the carriers Akagi, Hiryu, Kaga, Shokaku, Soryu, and Zuikaku swept in over the Hawaiian island of Oahu and devastated the American battleships around Ford Island in Pearl Harbor. Virtually unopposed, the enemy planes sank the USS Arizona and West Virginia, capsized the Oklahoma, and damaged the California, Maryland, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee. A total of 2,403 American servicemen were killed and 1,178 wounded in the attack.

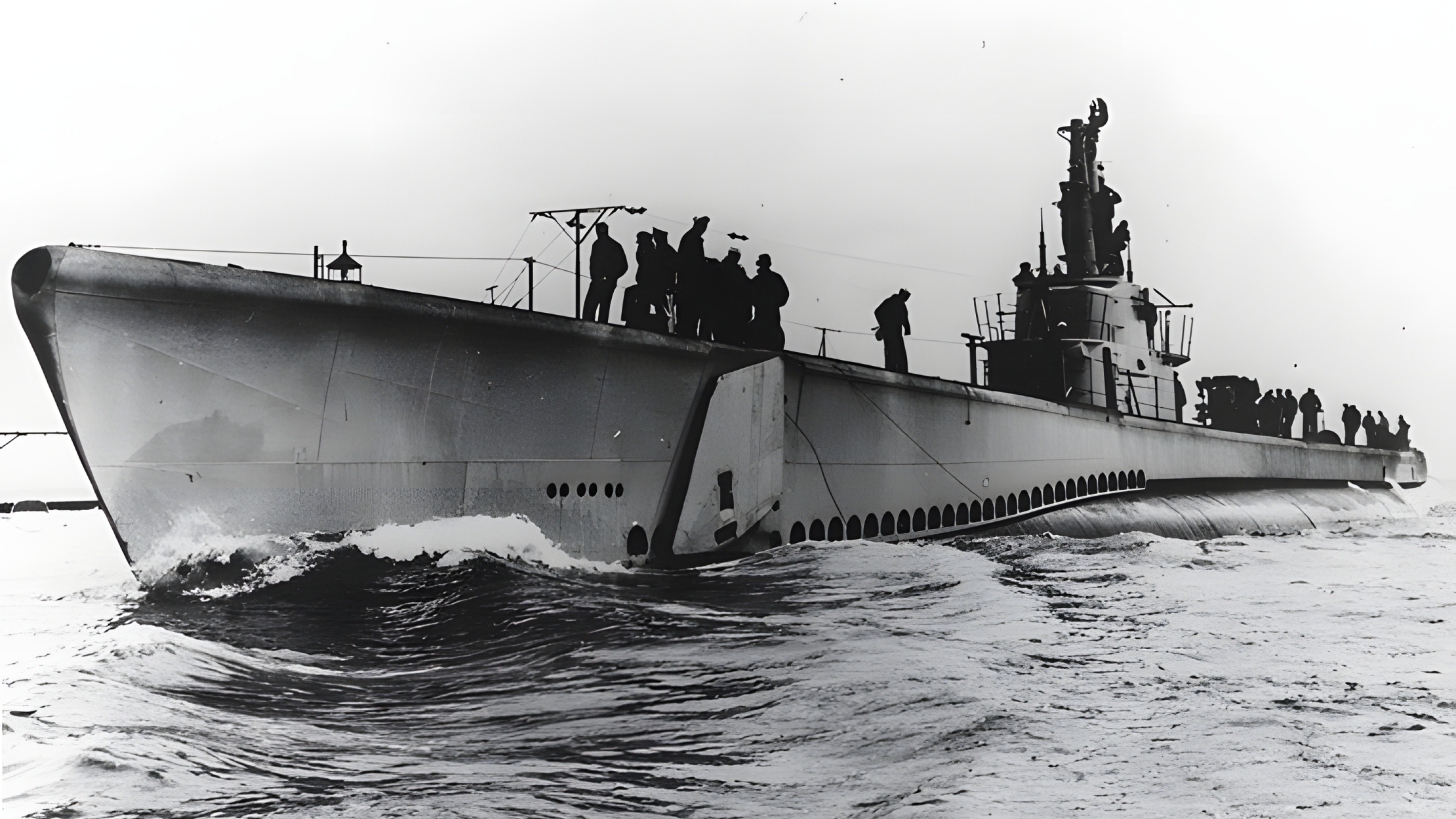

The masterful Japanese operation dealt the U.S. Pacific Fleet a staggering blow, though it was less than complete. The American fleet’s three precious carriers—Lexington, Saratoga, and Enterprise—were fortunately out to sea on maneuvers, and the enemy raiders overlooked such strategically vital targets as the Pearl Harbor oil tank farm, repair workshops, and submarine pens.

News of the attack electrified the Japanese people, and Yamamoto’s reputation soared. Viewed as the Horatio Nelson of Japan, he was then, indeed, free to “run wild” for several months as powerful Japanese naval formations supported thrusts against unready British and American bases in the Far East: Hong Kong, Singapore, Guam, Wake Island, Midway, Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, the Solomon Islands, the Philippines, and New Guinea. But Admiral Yamamoto’s misgivings persisted about the wisdom of the Japanese Empire’s expansionist strategy.

Yamamoto: An Uncommon Sailor

Born on April 4, 1884, Isoroku Yamamoto (the name means “base of the mountain”) was the seventh child of Sadayoshi Takano, a cultured but impoverished primary schoolmaster of the samurai class in the city of Nagaoka on the bleak, isolated western coast of Japan’s main island, Honshu. His first name meant “fifty-six,” the age of his father at the time he was born. The boy grew up in a little wooden house, and his childhood was hard. Rice was scarce and life rigorous with gardening in the summer, the clearing of deep snows during the harsh winters, and fishing all year long. Isoroku secured part of his early education from Christian missionaries, although he never became a believer.

A short, slender lad with a protruding lower lip and thoughtful, easygoing demeanor, Isoroku was often ill and regularly suffered from influenza. He read the Bible, wrote poetry, was exposed to the English language, and became interested in the British and American cultures. His father had told him that America was peopled by hairy, odorous barbarians who ate flesh, but the intelligent boy was soon able to discount such fables. Isoroku and his family and friends enjoyed taking box lunches to the playing fields around his school, where they watched baseball games. The American national pastime was then becoming a favorite sport in Japan.

But Isoroku’s great love was gymnastics, in which he excelled and gained physical strength. In later years, then broad shouldered and barrel chested, he could not resist showing off by doing headstands on the rail of a ship or boat. He referred to himself as a “country boy” who became “just a common sailor,” but he was actually far from common.

While in middle school during the 1890s, Isoroku, like thousands of other Japanese boys from several prefectures, took part in annual maneuvers led by Army officers. The youngsters carried real weapons but not live ammunition. This was an adventure Isoroku looked forward to each year.

He decided on a career in the Navy “so I could return Admiral [Matthew] Perry’s visit.” Therefore, as the new century dawned, the youth applied for admission to the Naval Academy at Etajima on the Inland Sea. Out of 300 applicants, he scored second highest in the entrance examination. He was 16 years old. The academy regimen was rigid and spartan, with the cadets forbidden to drink, smoke, eat sweets, or associate with girls. The fourth year of the course was spent aboard naval vessels. Isoroku ranked seventh in the class of 1904.

The Last Great Battle of Ironclads

He was just in time to take part in the Russo-Japanese War, which had broken out that February. The young ensign went to sea with the Imperial Fleet and did not have to wait long for his baptism of fire. As a gunnery officer aboard the cruiser Nisshin covering the flagship of Admiral Heihachiro Togo, Yamamoto saw action in the destruction of the Russian battle fleet in the Strait of Tsushima between Japan and Korea on May 26-28, 1905.

In the first and last great fleet encounter of ironclads in the predreadnought era, superior Japanese seamanship and gunnery annihilated the Russian force. The Russians lost all 12 of their major ships. Never in history had a naval battle between apparently closely matched fleets ended with so complete a victory. The British-educated, unassuming, and ruthless Admiral Togo became a national hero.

At Tsushima on May 27, Ensign Yamamoto was knocked unconscious and wounded when a shell hit the Nisshin. His body was peppered by shell fragments, and he lost an orange-sized chunk of his thigh and two fingers from his left hand. After spending two months in a hospital, he returned home to Nagaoka for a hero’s welcome and sick leave. Soon after his recovery, he went back to gunnery school, was promoted to commander, and served at the Imperial Naval Headquarters in Tokyo. In the meantime, he went on training cruises to China and Korea, and in March 1909 his squadron paid brief visits to ports on the American West Coast.

“Special Student in English”

Isoroku’s career moved into high gear when he was appointed to the Naval Staff College in 1913. There, his intelligence and energy gave him an advantage over his carousing fellow officers. Though he had a strong sexual appetite, Isoroku had learned early that he could not tolerate alcohol in large quantities, so he practiced temperance. But he was a ferocious gambler, often staying up half the night to play shogi (the Japanese version of chess).

In 1913, Isoroku’s father and mother died, and, according to Japanese custom, the young man was adopted by the Yamamoto family. Advancement in the Navy came rapidly for him. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1914, lieutenant commander in 1915, and attended the Navy Staff College in 1916.

After several love affairs with geishas and a brief courtship, Yamamoto married a sturdy but pretty housemaid named Reiko in August 1918. They would have two sons and two daughters. The couple had no sooner set up housekeeping than they were separated. Yamamoto was posted to the United States as a “special student in English” at Harvard University, and he sailed in April 1919. Occupying rented rooms in the Boston suburb of Brookline, he studied economics and petroleum sources at Harvard along with 70 of his fellow countrymen.

Yamamoto adapted smoothly to life in America and learned to play bridge and poker, which appealed to his temperament with its mixture of bluff, luck, and anticipation. Poker became one of his life’s passions. When a friend asked him how he had learned bridge so quickly, Yamamoto explained, “If I can keep 5,000 ideographs in my mind, it is not hard to keep in mind 52 cards.” He amused his American hosts with impromptu acrobatics and juggling plates.

But he was a diligent student. He read omnivorously, became proficient at English, and slept only three hours a night. He learned all he could about oil, knowing that it was the life blood of a modern navy, and several oil companies offered him jobs. While at Harvard, Yamamoto also developed a lively interest in naval aviation, which had been pioneered by the Royal Navy in 1912. Completed in September 1918, HMS Argus was the world’s first operational flush-deck aircraft carrier. Yamamoto’s focus on naval aviation would stand him in good stead in the years ahead.

Denunciation of the Washington Naval Treaty

The up-and-coming young officer returned to Japan in 1921 and was promoted to commander. In 1924, he was given his first major assignment as executive officer of a new naval air station at Lake Kasumigaura, 40 miles northeast of Tokyo. Built at the suggestion of a British advisory mission, the station was the training ground for most of Japan’s naval aviators.

Yamamoto soon became one of his country’s leading experts in military aviation. Promoted to captain, he commanded the light cruiser Isuzu and the carrier Akagi in 1926 and returned to the United States that year as a naval attaché in Washington. During his two-year stint there, he learned much about American power as a whole but formed a lower opinion of the U.S. Navy, which he described as a club for golfers and bridge players.

By now promoted to rear admiral, Yamamoto served as a delegate to the London Naval Conference in 1929-1930, took command of the fledgling First Air Fleet in 1930, and was assigned to the Naval Air Corps headquarters in charge of the Imperial Navy’s technical service. Having learned to fly while a captain and receiving his wings at the age of 40, he vigorously championed naval aviation, convinced that aircraft carriers would one day relegate battleships to a secondary fleet role. Yamamoto strove to improve the quality of naval aircraft and demanded the development of a fast carrier-borne fighter that eventually resulted in the highly effective Mitsubishi Zero.

He took command of the 1st Carrier Division in October 1933, and by 1935 was a vice admiral and vice minister of the Imperial Navy. Yamamoto’s emphasis on naval aviation intensified, and he clashed with traditionalist colleagues who argued for more battleships. Yamamoto had little faith in such venerable behemoths. “They are like elaborate religious scrolls which old people hang in their homes,” he said, “as a matter of faith, not reality…. In modern warfare, battleships will be as useful to Japan as a samurai sword.” When fellow admirals called for a program to build two gigantic battleships, saying that only a battleship could sink a battleship, Yamamoto resisted. He quoted an Oriental proverb: “The fiercest serpent may be overcome by a swarm of ants.”

Nevertheless, as the chief Japanese delegate to the London Naval Conference in 1934-36, Yamamoto stepped into the international limelight by forcing the termination of a treaty that had kept Japan’s battleship fleet inferior to those of Great Britain and America by a ratio of 5:5:3. He returned home a national hero and continued to lobby for the construction of carriers. The flattops Akagi and Kaga, already in service, were joined by faster and more sophisticated models, long-range flying boats entered service, and the formidable Zero was developed.

“To Fight the United States is Like Fighting the Whole World”

As Navy minister and commander of the 1st Fleet, Yamamoto oversaw an extensive buildup and modernization of the Imperial Navy and its air services in the late 1930s. Unorthodox in his training methods, he sometimes placed tacks on the chairs of staff officers to teach them vigilance and made them play poker in order to master the arts of bluff and surprise. Yamamoto often told Commander Yasuji Watanabe, one of his favorite staff officers, that gambling—half calculation and half luck—was a major factor in his thinking.

Yet, while he fought for increased naval power he continued to oppose the militarists and denounced the Tripartite Pact. Negotiated in Tokyo and signed in Berlin on September 27, 1940, by Japan, Nazi Germany, and Italy, it was intended primarily to assure mutual aid and to forestall American intervention in World War II. Yamamoto had been so outspoken against war in the late 1930s that he was in danger of being assassinated by extremists. When a plot to kill him was uncovered in July 1939, he was saved by being promoted to admiral and sent to sea as commander in chief of the Combined Fleet.

Yamamoto had vigorously warned against war with America and Britain, but East-West tensions heightened and diplomatic efforts began to fall apart. In the spring of 1940, Admiral Yamamoto paced the deck of his flagship, the battleship Nagato, with his chief of staff, Rear Admiral Shigeru Fukodome, and watched impressive maneuvers by carrier-based fighters. The fleet commander said, “I think an attack on Hawaii may be possible now that our air training has turned out so successfully.” In one crushing samurai blow, he reasoned, the American fleet at Pearl Harbor would be crippled, and before it could be rebuilt Japan would have seized Southeast Asia with all of its resources.

Yet the misgivings continued to torment Yamamoto as the Far East situation worsened and the prospect of hostilities loomed. “It’s out of the question,” he remarked in October 1940. “To fight the United States is like fighting the whole world. But it has been decided, so I will fight my best. Doubtless I will die on board the Nagato.” Almost a year later, addressing a Tokyo meeting of his old Nagaoka schoolmates on September 18, 1941, Yamamoto warned, “It is a mistake to regard Americans as luxury loving and weak. I can tell you that they are full of spirit, adventure, fight, and justice. Their thinking is scientific and well advanced…. Remember that American industry is much more developed than ours, and, unlike us, they have all the oil they want. Japan cannot vanquish the United States. Therefore we should not fight the United States.”

But the warnings were now of no avail as Japan rushed toward war. An imperial conference had agreed that a confrontation with America was inevitable, and the Japanese militarists triumphed when scrawny, bespectacled General Hideki Tojo, a longtime admirer of Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler, was appointed prime minister in October 1941. So, Admiral Yamamoto resigned himself to his country’s fate and directed his considerable skills toward war-making. He pushed the plan—drawn up by his eccentric operations officer Captain Kameto Kuroshima—for a preemptive strike against the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor as Japan’s only course. Yamamoto’s colleagues demurred, saying it was too risky and that the probable loss of two or three carriers was too high a price to pay. But Yamamoto argued, cajoled, and threatened, and eventually the “Operation Kuroshima” plan was adopted.

The December 7 attack was a brilliant tactical success, making Yamamoto a national hero overnight in the mold of Admiral Togo. Japanese victories in the Pacific War that followed added to his prestige, but, as he had predicted, the euphoria was to be short lived. In April 1942, American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers led by Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle left the carrier USS Hornet and bombed Japan. The daring raid inflicted only slight damage, but Japan’s confidence was shaken and its military establishment humiliated. This was followed by the Battle of the Coral Sea on May 4-8, 1942. Both the U.S. and Japanese fleets suffered heavy losses, but the Americans thwarted Japan’s advances in the South Pacific.

Then, only six months after his master stroke at Pearl Harbor, Admiral Yamamoto suffered the first major Japanese naval defeat since the 16th century.

Japanese Disaster at Midway

After the Doolittle Raid, Yamamoto made a fateful decision to seek a decisive battle with the “remnants” of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s Pacific Fleet by attacking the American base on tiny Midway atoll, 1,110 miles northwest of Pearl Harbor. The Japanese admiral chose this action rather than a more circumspect course of remaining on the strategic defensive and taking advantage of his numerical superiority in carriers, supported by the extensive ring of island air bases lying across the Americans’ expected line of attack in the Central Pacific. The scheme called for the deployment of several task forces ranging from the Central Pacific to the Aleutian Islands.

The plan was complex, risky, and involved too much dispersal of his forces, and the Navy General Staff initially rejected it. Yamamoto justified it as necessary to close a gap in the Japanese defenses, and the General Staff acceded after the Doolittle Raid. Yamamoto sought to lure the American fleet to fight at a place and time of his own choosing. The capture of Midway would have been followed by a landing in the Hawaiian Islands. But, although Yamamoto’s fleet enjoyed a numerical superiority in ships and aircraft, the Americans held a trump card. American codebreakers at Pearl Harbor were reading major portions of Japanese naval communications and advised Nimitz that the Japanese would strike Midway.

The result was that at Midway on June 4-6, 1942, the overconfident Japanese fleet was outmaneuvered and forced to withdraw by a much smaller American force that had the advantage of surprise, better planning, and luck. In the hard-fought, four-day battle, Nimitz lost the valuable carrier USS Yorktown, the destroyer USS Hammann, 150 planes, and 307 men. But Yamamoto lost his four carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu, plus 275 planes and more than 4,000 men. These included 100 experienced pilots who could not be replaced.

The Combined Fleet commander had conceived a sound strategy, but a flawed one. He failed to muster all available force for his main effort, was not positioned so that he could control the action, and was careless about deploying reconnaissance and screening units.

Midway, America’s revenge for Pearl Harbor, was the turning point in the Pacific War and the most decisive naval encounter since Nelson’s defeat of the French and Spanish fleets at Trafalgar on October 21, 1805. It assured the final Allied victory in the Pacific. Midway was the finest hour for Admiral Nimitz and his heroic carrier crews. For Admiral Yamamoto, Midway was the tragic climax of his long career and an indescribable blow. Too stunned to speak, he could only groan as he read the battle reports.

Together with the Battle of the Coral Sea, the American triumph at Midway prevented an inevitable and disastrous invasion of Hawaii, ended six months of Japanese ascendancy in the Pacific, and made possible a U.S. counteroffensive—the invasion of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands by the 1st Marine Division on August 7, 1942. Japan was now forced onto the defensive, unable to mount major offensives and obliged instead to consolidate its gains. The Americans, meanwhile, began their great island-hopping campaign that took them to the shores of Japan itself.

The Death of Admiral Isoruoko Yamamoto

After Midway, Admiral Yamamoto retained his high reputation and fought on. But he was drawn into a war of attrition as he struggled to prevent the Allied forces from seizing the Solomons and eroding Japan’s position in the South Pacific. Directing operations from the super battleships Yamato and Musashi, Yamamoto scored some successes against U.S. naval units around Guadalcanal, but his forces were unable to prevent the Americans from prevailing at sea and eventually winning the big island.

From August 1942 until his death the following spring, this struggle on the periphery of the empire rapidly consumed Japanese fleet and air strength. It was a losing battle, and Yamamoto knew it. While putting in at the big Combined Fleet base at Truk in the Caroline Islands on August 28, 1942, he wrote to a friend, “I sense that my life must be completed in the next 100 days.”

On April 3, 1943, he shifted his headquarters from Truk to Rabaul in New Britain, and two weeks later flew out to inspect Japanese bases in the northern Solomons. Characteristically, he was not hesitant to venture into a combat zone, but once again he fell victim to U.S. intelligence. Admiral Nimitz was given decoded information on Yamamoto’s movements, and he asked Washington if it would be in America’s best interests for him to be eliminated. The answer was “Yes.”

The end came for Yamamoto on Saturday, April 18, 1943, exactly a year after the famous Doolittle Raid. On that day, a flight of 16 Army Air Forces Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters from Henderson Field at Guadalcanal, led by Colonel Thomas G. Lanphier Jr., ambushed Yamamoto’s green-striped Mitsubishi G4M Betty bomber as it approached an airfield on the island of Bougainville and shot it down. The burning plane crashed in dense jungle, and there were no survivors. The admiral’s remains were recovered and sent to Japan aboard the destroyer Yugumo.

“An Insupportable Blow”

In Tokyo, Emperor Hirohito awarded Yamamoto the Grand Order of the Chrysanthemum, First Class, and promoted him posthumously to admiral of the fleet. German dictator Adolf Hitler made Yamamoto the only foreign recipient of the Knight’s Cross with Swords.

The death of their greatest admiral since Togo was recorded as “an insupportable blow” to the Japanese people. He was guilty of some costly strategic mistakes, but he had few modern peers in naval leadership. As Goro Takase, one of his Combined Fleet staff officers, said, “His concern for subordinates struck the heart of every sailor, and each was ready to die for him. His leadership pervaded the lowest reaches of the Navy and inspired every man. There was never any wavering in his command.” Yamamoto’s successor, Admiral Mineichi Koga, said, “There was only one Yamamoto, and no one can replace him.”

Admiral Yamamoto’s state funeral in Tokyo on June 5, 1943, featured one of Japan’s last great wartime parades. A million people lined the streets. The hero’s ashes were placed in two urns. One was deposited in Tokyo’s Tamabuchi Cemetery alongside Admiral Togo’s ashes, and the other was buried beside the ashes of his father in Nagaoka. As requested, Yamamoto’s modest grave marker was cut an inch shorter than that of his father.

A certain amount of revisionism regarding Yamamoto has arisen over the years. In actuality, he was thoroughly pragmatic and took his views of the US in that light. The one thing he overlooked was American tenacity. Even if his original plan for a victory at Midway, Coral Sea and the Solomons was successful, it would only have meant that the inevitable Japanese defeat would have taken a little longer. The signal example was the American Civil War when it took almost three years for the Union forces were able to employ coordinated strategic campaigns instead of each army commander going out on his own. To be sure, the Admiral was probably the best they had but a comparison of the assets and abilities of both countries pretty much dictated the final result.