By Michael D. Hull

History was made in the Mediterranean Sea on the night of Monday, November 11, 1940, when the Italian Navy’s battle fleet was devastated at Taranto, off the Ionian coast of southern Italy.

In Operation Judgment, 21 lumbering but resilient Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers of Admiral Sir Andrew “ABC” Cunningham’s British Mediterranean Fleet flew 150 miles at low level to attack the Italian base. The surprise raid—the world’s first such carrier-based operation—resulted in the torpedoing of one new and two old battleships. A cruiser and the dockyard were also damaged, and only one Italian battleship was left operational.

The Swordfish biplanes, based on the new carrier, HMS Illustrious, flew in two attack waves and used 11 torpedoes. Two aircraft were lost. Though modest by later standards, the raid forced the Italian Navy to move the rest of its ships to safer harbors on the Italian west coast and tilted the critical balance of naval power in the Mediterranean in favor of the British.

Taranto was a bold stroke, a textbook naval feat that would influence Japanese plans for the December 7, 1941, raid on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. Yet, ironically, the British, who had invented the aircraft carrier during World War I, still seemed reluctant to fully grasp its potential and the vulnerability of surface vessels from aerial attack. This was to be demonstrated tragically in the Far East just over a year after the Taranto operation.

Strengthening the British Fleet in Southeast Asia

Although Britain had suffered serious naval losses in the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean by late 1941, it was decided that she needed to strengthen her forces in Southeast Asia in an attempt to deter expansionist Japan from entering the war. So, the new 35,000-ton battleship HMS Prince of Wales was deployed to the Pacific in October 1941. She joined up with the modernized battlecruiser HMS Repulse (32,000 tons) at Trincomalee, Ceylon. They were the only capital ships the Allies then had in the western Pacific.

“We had only one key weapon in our hands,” announced Prime Minister Winston Churchill. “The Prince of Wales and the Repulse had arrived in Singapore. They had been sent to these waters to exercise that kind of vague menace which capital ships of the highest quality whose whereabouts is unknown can impose upon all hostile naval calculations.”

During an earlier lapse into wishful thinking, Churchill had assured the Commonwealth prime ministers, “In my view, Prince of Wales will be the best possible deterrent” to Japanese aggression.

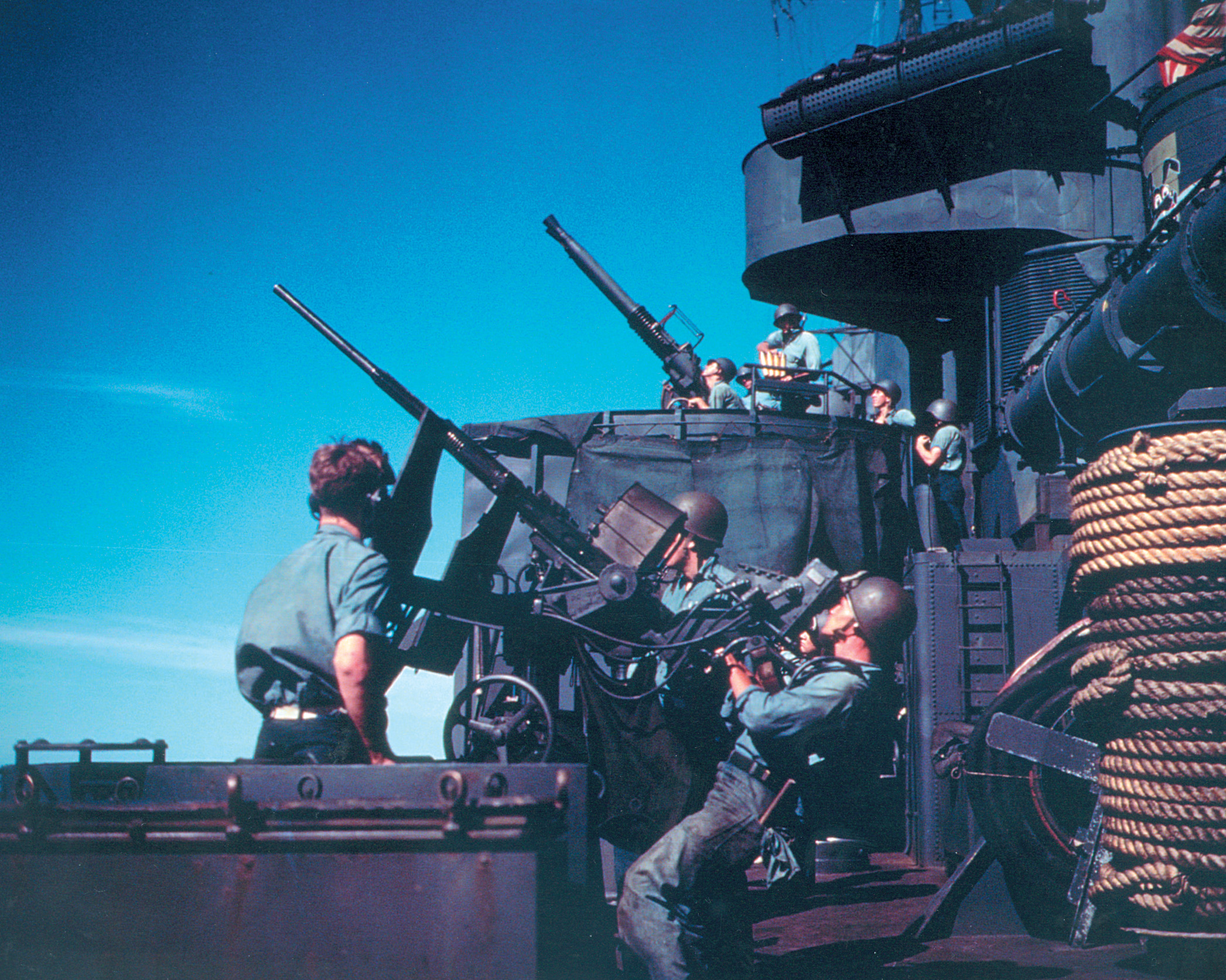

A battleship of the King George V class, the Prince of Wales was laid down in 1939 and commissioned in the spring of 1941. Her armament included 10 14-inch guns, 16 5.25-inch dual-purpose guns, between 64 and 88 two-pounder pompoms, eight 40mm Bofors guns, and up to 38 20mm Oerlikon guns. The vessel’s design embraced the most up-to-date thinking in naval architecture and incorporated comprehensive protection against bomb and torpedo attack.

Her skipper was Captain John C. Leach, who had distinguished himself on her bridge during the historic pursuit and sinking of the powerful German battleship Bismarck in late May 1941. Prime Minister Churchill described him as “a charming and lovable man, and all that a British sailor should be.”

Laid down in January 1915 and completed in August the following year, the 750-foot-long Repulse carried six 15-inch guns, 15 four-inch guns, two three-inch guns, a 12-pounder field gun, five machine guns, 10 Lewis guns, and 10 21-inch torpedo tubes. She was under the command of Captain William G. Tennant, a gallant organizer of the brilliant Dunkirk evacuation in May-June 1940.

Force Z Under the Unqualified Tom Philips

The combined force was designated Force Z and placed under the overall command of 53-year-old Rear Admiral Sir Tom Spencer Vaughan Phillips, who was flying his flag on the Prince of Wales. Short, self-assured, and hardworking, Phillips had joined the Royal Navy in 1903, was a navigator by profession, and, as vice chief of naval staff, was regarded as the Admiralty’s brains during the early months of World War II. Long desk-bound, his only recent command experience at sea was eight prewar months with the Home Fleet, during which he had the misfortune to become involved in a collision. He worked well with Churchill when the latter became First Lord of the Admiralty in September 1939. But “Tom Thumb” Phillips became unpopular professionally because of his perceived subservience to Churchill, for meddling in operational matters, and for accusing seagoing officers of lacking aggressiveness.

When Admiral Sir John Tovey, commander in chief of the Home Fleet and a heroic destroyer skipper during World War I, stressed during a briefing the need for air cover for ships at sea, Phillips, according to an officer present, “blew his top and virtually accused Tovey of being a coward.”

Phillips was considered woefully unqualified for high command at sea by senior admirals. Admiral Cunningham, the Mediterranean Fleet commander and Britain’s top fighting admiral of World War II, was disturbed about Phillips’s Force Z assignment. “What on earth is Phillips going to the Far East Squadron for?” he asked. “He hardly knows one end of a ship from the other.”

The 23,000-ton fleet carrier HMS Indomitable should have joined the two capital ships in order to provide vital air cover, but she was damaged after running aground in the British West Indies. Her absence, and that of other intended components, turned a questionable tactical decision into a hazardous enterprise.

Underestimating Japanese Strength

Force Z arrived at the British bastion of Singapore on December 2, and was there on December 8, the day after the Pearl Harbor raid and when Japanese forces began their successful Malayan campaign. Admiral Phillips requested that Hawker Hurricane fighters be made available for air protection but was told that there were none. All that was available was an inexperienced Australian squadron of slow, undergunned Brewster Buffalo fighters.

On the evening of Monday, December 8, the Prince of Wales, Repulse, and four escorting destroyers weighed anchor from Singapore. Word had been received that Japanese invasion transports were heading for the north of the Malayan Peninsula, and Admiral Phillips planned a surprise attack against them off Kota Bharu. Not only did his Force Z lack air protection, but he also learned after his departure that he could not count on aerial reconnaissance or fighter cover because the enemy had overrun the airfields in northern Malaya.

The Japanese invasion fleet, led by Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita, was at full strength and included two battleships escorting 28 troop transports. It was a large-scale invasion, with simultaneous landings scheduled for Malaya and Thailand. The fleet was supported by 99 bombers, 39 fighters, and six reconnaissance planes of the 22nd Air Flotilla based at Saigon and Soktran in French Indochina. Phillips was ignorant of the Japanese plans, and also of the enemy’s sea, air, and ground strength.

On the rainy, cloudy afternoon of Tuesday, December 9, the British fleet was deep in the Gulf of Siam when it was sighted by three Japanese reconnaissance planes and a submarine. The element of surprise was gone, so Phillips decided to return to Singapore. At that time, Kurita’s force was only 15 miles to the north. The 22nd Air Flotilla was getting ready to attack Singapore when the submarine reported that Force Z was at sea. Torpedoes were hastily loaded aboard the Japanese bombers, and they took off at 6 pm to hunt for the British ships. But the enemy planes never located them and returned to their bases.

Admiral Phillips was still heading back to Singapore when he received a message that Japanese troops were landing at Kuantan, halfway down the Malayan eastern coast. He decided to investigate. His fleet arrived off Kuantan at dawn on Wednesday, December 10, but all was quiet there. The report had been in error. When a Japanese tugboat was reported to the north, Phillips ordered a new course at 10 am to check the sighting. Meanwhile, Force Z had been attacked at 2:30 am and not been aware of it. A submarine had fired five torpedoes at the British ships, but all missed. Phillips’s crews had not even seen the torpedoes.

Admiral Nobutake Kondo, the able commander in chief of the Japanese invasion forces, was receiving continuous reports about Force Z. He ordered all available naval aircraft to attack during the early morning hours of December 10 while his fleet steamed southward at top speed to intercept the British ships. Formations of reconnaissance planes and twin-engine Mitsubishi Nell and Betty bombers carrying bombs and torpedoes headed southward from Indochina. Japanese pilots fanned out across a wide area in their search for the British ships.

While woefully uninformed about the nearing enemy threat, Admiral Phillips was confident that his ships could withstand an air attack by the Japanese. He believed that the Prince of Wales was unsinkable and that the thinly armored Repulse could protect herself. The admiral had once been quoted as saying that “bombers are no match for battleships.” Fatefully, Phillips was to keep radio silence during Force Z’s operations, believing that he would automatically be provided with air cover if he ran into serious trouble.

“Stand by For Barrage!”

The rude awakening in store for “Tom Thumb” Phillips and his fleet came on December 10. Although the 22nd Air Flotilla was about to give up hope of locating the British ships, an ensign aboard a Japanese reconnaissance plane sighted the Repulse and Prince of Wales at 11 that morning. He reported breathlessly, “Sighted two enemy battleships 70 nautical miles southeast Kuantan, course southeast.” The Japanese pilots wasted no time in acting.

Nine twin-engine bombers approached Repulse in tight formation and line abreast as shipboard observers shouted, “Enemy aircraft in sight. Action stations!” The battlecruiser’s skipper, Captain Tennant, ordered his guns to open fire. He watched with tightness in his throat as the batteries roared and the enemy bombers flew closer, unwavering through the intense barrage. Tennant saw bombs fall toward the Repulse and was relieved when only one hit amidships. It exploded on the armored deck in the Royal Marine detachment’s mess. The Japanese planes then droned away through flak bursts. Repulse damage crews swiftly got fires under control, but Captain Tennant knew that the fleet’s ordeal was just beginning.

At 11:30 am, a radar operator reported enemy torpedo bombers speeding toward Prince of Wales. Two groups of 16 planes flew ahead of the battleship and disappeared momentarily in the clouds at an altitude of 3,000 feet. Then, at 11:42 am, they suddenly dived toward the port side of the ship in clusters of two and three planes. Bugles blared aboard the Prince of Wales, and an alarm shrilled: “Stand by for barrage!” A withering fire erupted from the vessel’s heavy rifles, antiaircraft batteries, and machine guns, but the enemy torpedo bombers bore through unscathed to drop their missiles. Other planes raced toward the Repulse. Captain Tennant ordered his navigation officer to “turn 45 degrees to starboard.”

The battlecruiser skipper marveled at the audacity of the enemy air crews, who pressed their attacks through heavy fire. Aboard the Repulse, CBS radio correspondent Cecil Brown heard a sailor mutter, “Look at those yellow bastards come.” Another rating said, “Plucky blokes, these Japanese. That was as beautiful an attack as ever I expect to see.” The British sailors cheered when an enemy plane exploded with a roar. One daring torpedo plane pilot flew alongside the ship and challenged its gun crews. He paid for the brazen stunt when his plane was blown apart.

The Doomed Repulse

The Repulse completed the 45-degree turn, with her stern now offering a smaller target to the Japanese planes. Their torpedoes passed harmlessly on each side. Despite her age, the battlecruiser was highly maneuverable and able to dodge the enemy aircraft. But the persistent raiders then raked the ship’s gun crews with machine-gun fire, and many sailors perished at their mounts.

Another journalist aboard the Repulse, O’Dowd Gallagher of the London Daily Express, turned in a vivid exclusive report of the ship’s ordeal for his readers:

“I saw glowing tracer shells describe shallow curves as they went soaring skyward surrounding the enemy planes. Our ‘Chicago pianos’ (pom-poms) opened fire; also our triple-gun four-inch high-angle turrets. The uproar was so tremendous I seemed to feel it. From the flag deck I can see two torpedo planes. No, they’re bombers. Flying straight at us…. There is a heavy explosion, and the Repulse rocks. Great patches of paint fall from the funnel on to the flag deck….

“Cooling fluid is spurting from one of the barrels of a ‘Chicago piano.’ I can see black paint on the funnel-shaped covers at the muzzles of eight barrels actually rising in blisters big as fists. The boys manning them—there are 10 to each—are sweating, saturating their asbestos anti-flash helmets. The whole gun swings this way and that as spotters pick planes to be fired at….”

Despite his own problems, Captain Tennant kept a close eye on the Prince of Wales only 2,000 yards away. The flagship had been struck by some of the enemy torpedoes, and the Repulse skipper was dismayed to see black smoke belch from her stern and vitals. The flagship was listing 13 degrees to port and weaving uncertainly at 15 knots. She was rapidly losing headway. Tennant realized that the Prince of Wales must have taken two torpedoes in her rudder and propeller shafts. He watched the battleship try to turn, succeeding only in heeling over as water poured into her hull, and then saw flagship ratings hoist “not under control” signals.

Tennant fired off signals to the stricken flagship but received no response. So, believing that the Prince of Wales was unable to do so, he sent an emergency radio signal to Singapore at 11:50 am saying that Force Z was being bombed. This was the first word that headquarters had of the attack. Within seven minutes, a flight of Royal Air Force Brewster Buffalos was dispatched from the Sembawang airfield on Singapore Island.

After managing to avoid high-level Japanese bombers, Captain Tennant reduced speed to 20 knots and moved the Repulse closer to the Prince of Wales to offer assistance. Again there was no response. Then it was the aging battlecruiser’s turn again when nine enemy torpedo bombers were spotted low on the horizon. Torpedoes were dropped at a range of 2,500 yards, and one struck amidships with “a great jarring shudder.”

Yet the Repulse steamed on, with her four-inch guns and pom-poms throwing up a curtain of protective fire. At the same time, the Prince of Wales took two more torpedo hits and was incapable of maneuver. Her speed had fallen to eight knots.

More Japanese torpedo bombers made a concentrated effort on the Repulse, attacking from all directions. She took four hits, shuddered, and listed heavily to port. “The ship seemed to stagger in her stride,” reported one of her officers, “and I knew instinctively that this was the end, that Repulse was doomed.”

“Prepare to Abandon Ship”

Captain Tennant was sure that his ship could not survive four torpedoes and ordered everyone to come on deck. In a steady voice, he called over the loudspeakers, “All hands on deck. Prepare to abandon ship. Clear away Carley floats!” Men filed topside as explosions tore at the interior of the ship.

As the battlecruiser reached a 30-degree list, Tennant watched from the bridge as about 200 men collected on the starboard side, waiting for word to leave the ship. The skipper’s commanding presence calmed his men. “I never saw the slightest sign of panic or ill discipline,” he recalled later. “I told them from the bridge how well they had fought the ship, and wished them good luck.”

After the wounded had been evacuated, men slid into the calm, tepid ocean and swam toward the Carley floats. As they swam for their lives, the sailors gave three cheers for their skipper and the Repulse. Oil gushing from the ship’s ruptured bunkers spread through the waters, and many survivors choked to death while struggling for the floats.

Japanese planes flew overhead but did not strafe the men in the water. The sailors had fought gallantly, and some of the enemy fliers felt a strange sympathy for the Royal Navy, which had served as a prewar model for their own Imperial Navy. One Japanese pilot admitted later to his squadron leader, “As we dived for the attack, I didn’t want to launch my torpedo. It was such a beautiful ship, such a beautiful ship.”

By now listing at almost 70 degrees to port, the gallant Repulse stayed afloat for six or seven minutes and then rolled over at 12:33 pm. Ordered by Admiral Phillips, the destroyers HMS Electra and HMS Vampire eased in to pick up the survivors—42 out of 66 officers including the skipper and 754 out of 1,240 ratings. The rescue effort was not hindered, for the enemy had a more important prey to finish off.

The Repulse was gone, though incredibly the mortally wounded Prince of Wales was still afloat and steaming northward at eight knots. But she was rapidly filling with water.

90 Officers and 1,195 Ratings Rescued

Soon after the Repulse went down, nine high-level Japanese bombers flew over the Prince of Wales, turned, and came in to attack 10 minutes later. Forward guns that had not been shot out opened fire at the unwavering enemy formation. As grief-stricken Admiral Phillips and staff officers on the flagship’s compass platform watched the enemy bombs fall, Captain Leach shouted, “Now!” Everyone dropped to the deck just before the bomb pattern hit the ship aft. Luckily, only one bomb struck home, causing superficial damage. But it staggered the battleship, and she began to founder. Admiral Phillips was dismayed by the destruction aboard his proud flagship as stretcher parties scrambled to tend wounded ratings.

The Prince of Wales had somehow withstood her last attack, but she was dying minute by minute. Her beams were almost awash. At 12:50 pm, a signal was sent to Singapore: “Emergency. Send all available tugs….” The desperate message was repeated 11 minutes later, but the flagship was beyond such far off succor. The destroyer HMS Express eased alongside the starboard quarter of the Prince of Wales and began to take off the wounded, and Carley floats were launched. By 1:10 pm, the doomed flagship was settling rapidly and listing heavily to port. It was all over for the Prince of Wales. Her skipper gave the order to don lifejackets and abandon ship.

Admiral Phillips and Captain Leach stood together on the bridge and waved to the departing crewmen. “Goodbye,” Leach called. “Thank you. Good luck. God bless you.” Phillips had called for his best hat to be brought up from his cabin, and neither man made any move to save himself.

Crammed aboard HMS Express, horrified survivors watched as the flagship heeled steeply to port at 1:20 pm, her keel rising while men scrambled down ropes or slid down her upturned bottom. Then the flagship capsized and sank, taking Admiral Phillips and Captain Leach with her. Ninety out of 110 officers and 1,195 out of 1,502 ratings were rescued.

As the Prince of Wales went down, 11 Australian Buffalo fighters from Sembawang arrived on the scene, prompting a distant formation of Japanese planes to jettison their bombs and head for home. The fighter pilots were shocked when they looked down to see the masses of men struggling in the water. They waved and gave the thumbs-up sign. The Buffalos patrolled overhead while the survivors of the two ships were picked up from the water or from Carley floats. At dawn the next day, December 11, 1941, Lieutenant Haruki Iki, leader of the Japanese 3rd Squadron, flew low over the sunken British ships and dropped bunches of flowers.

Force Z and Singapore: Two Crushing Defeats for the British

The destruction of Force Z had cost the Japanese only eight aircraft. It was established that the Prince of Wales had succumbed to four, and possibly six, 24-inch torpedoes with 1,210-pound warheads, and one bomb, while the Repulse was sunk by five torpedoes and one bomb. Only three days after the mauling of the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, the loss of the two British capital ships reduced Allied fortunes in the Far East to their lowest ebb.

During the week after the Force Z disaster, as the Royal Air Force was compelled to abandon its airfields, the defense of northern Malaya collapsed. The strategic foundations for securing Singapore, the major British bastion in the Far East, had crumbled. The campaign now degenerated into a gallant but hopeless retreat by poorly equipped, understrength British, Indian, and Australian units, outmaneuvered and outfought by Japanese assault troops advancing down the western coast of Malaya.

Prime Minister Churchill regarded Singapore as “a famous fortress” that had to be defended to the last, but despite reinforcements being rushed in its surrender was inevitable. That surrender occurred on February 15, 1942. The Malayan campaign was the most ignominious defeat in British military history.

The loss of the Prince of Wales and the Repulse both critically weakened the balance of Allied naval power in the Far East and dramatically removed any lingering doubts about the vulnerability of surface ships from air attack. The era of the invincibility of battleships—ironically, like carriers, a British conception—had passed.

While the sinking of the two ships sent shock waves through the Royal Navy and stunned the British people, no one was more shaken than Churchill. He was devastated, for only four months before the tragedy he had sailed on the Prince of Wales to meet for the first time with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in Placentia Bay, off Newfoundland.

“Over All This Vast Expanse of Waters Japan was Supreme”

During their historic Atlantic Charter conference on August 9-12, 1941, the quarterdeck of the Prince of Wales was the scene of a moving Sunday morning divine service attended by Churchill, Roosevelt, their chiefs of staff, and British and American sailors and Marines of all ranks.

“Every word seemed to stir the heart,” Churchill reported. “It was a great hour to live.” But almost half of those who sang the hymns chosen by the prime minister were dead four months later.

Churchill was opening dispatch boxes on December 10 when the telephone shrilled at his bedside. It was Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, the First Sea Lord. He coughed and gulped, and his voice sounded odd to Churchill as he reported the loss of the Prince of Wales and the Repulse. “Are you sure it’s true?” Churchill asked. The aging, ailing Pound, who had commanded a battleship at the Battle of Jutland in 1916, replied, “There is no doubt at all.” The prime minister put the telephone down dazedly.

“I was thankful to be alone,” he reported later. “In all the war I never received a more direct shock…. As I turned over and twisted in bed, the full horror of the news sank in upon me. There were no British or American capital ships in the Indian Ocean or the Pacific except the American survivors of Pearl Harbor, who were hastening back to California. Over all this vast expanse of waters Japan was supreme, and we everywhere were weak and naked.”

The next morning, December 11, Churchill made a full statement in the House of Commons on “the new situation.” He spoke of the long-drawn Libyan campaign hanging in the balance and warned that “very severe punishment awaited us at the hands of Japan.” But, ever ready to summon up hope, he said, “On the other hand, the Russian victories had revealed the fatal error of Hitler’s eastern campaign, and winter was still to assert its power. The U-boat war was at the moment under control, and our losses greatly reduced.

“Finally, four-fifths of the world were now fighting on our side. Ultimate victory was certain…. The House was very silent, and seemed to hold its judgment in suspense. I did not seek or expect more.”

What a great article. Thanks.

I have never heard about the chivalrous conduct of the Japanese pilots.