By Richard A. Gabriel

Of the thousands of commanders who have served in history’s armies, why is it that only a few are remembered as great leaders of men in battle? What combination of personal and circumstantial influences conspires to produce great commanders? What makes a great leader great? An analysis of the biographies of six of the greatest captains of the ancient world—Thutmose III of Egypt, Sargon the Great of Assyria, Hannibal of Carthage, Scipio Africanus, Philip II of Macedonia, and Caesar Augustus—helps identify the characteristics of intellect, psychology, and personality that made these men great military and political leaders. Unsurprisingly, these commanders possessed many of the same personality traits.

The ancient world is not as distant as it is usually thought to be. Ancient societies were often confronted by technological challenges equal to those faced in modern times. Thutmose III, for example, had to reform an Egyptian military system that had remained unchanged for almost 2,000 years. This called for new tools of war requiring sophisticated manufacture unfamiliar to Egypt. New tools, in turn, required radically different forms of military organization. Mass conscription, revised tactics, expensively trained soldiers, a professional officer corps, a logistics base, and a quartermaster corps all had to be invented out of whole cloth. Egyptian society, too, was forced to change. For 3,000 years, Egypt had been sealed off from the outside world. Now it had to confront that world and all its strangeness.

The psychological shock was enormous. Everything from new foods to new musical instruments flowed into Egypt, along with new ideas about everything from religion to political legitimacy. One of every 10 men was required to serve in the military, and for the first time in 3,000 years, Egyptian soldiers were sent beyond their borders to fight and live among strange cultures. When compared to the wrenching experience of Egypt’s emergence upon the world stage of power politics in the 16th century bc, the American entry into the Cold War following World War II seems like a minor event. The new Egyptian military order lasted for more than half a millennium. The Cold War lasted less than one-tenth that long.

Two Factors: Traits of Personality and Historical Circumstance

If the challenges of human life and technological change are essentially similar in ancient and modern societies, what might be learned from ancient cultures about what it takes to be a great leader? Two sets of factors are relevant to the emergence of such leaders. The first involves traits of personality and character that permit the great commander to comprehend his world as it is, even as he sees beyond it to the objectives he wishes to advance in the future. The second is the historical circumstance in which the commander finds himself. Great commanders are only possible when challenging times provide opportunities for their unusual abilities to come to the fore. Grave social and military crises create opportunities for leaders to arise who might otherwise have lived completely ordinary and unrecorded lives.

The connection between crises and the emergence of great leaders is often impossible to discern at the time, being revealed only through the hindsight of history. So it was that Hannibal’s deadly challenge to Rome made possible Scipio’s being offered a major military command at so young an age. Caesar’s murder transformed Augustus from a frail young man of supposedly limited ability into a major actor on the Roman political stage. The Mitanni security challenge to Egypt forced a young pharaoh to react and in the process become a great military and political leader.

Experiencing War at an Early Age

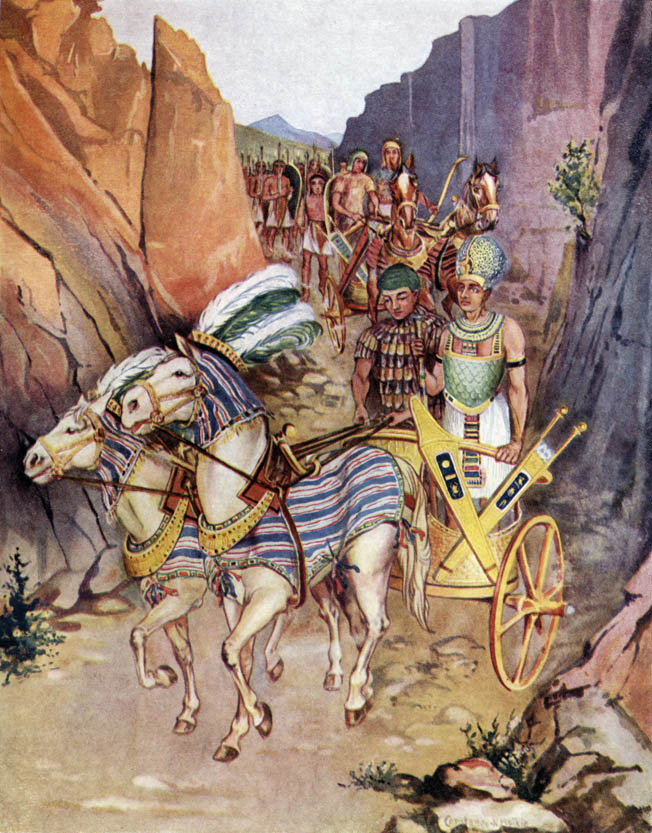

All the great captains of the ancient world, with one exception, experienced war at an early age. Thutmose III was the commander of the Egyptian Army at 16, and a year later led his first military expedition into Nubia. Two years after that, he recaptured Gaza. He was not yet 22 when he fought his most famous battle at Megiddo. There, in what is now modern-day Israel, Thutmose confronted a large Canaanite army under the rebellious kings of Kadesh and Megiddo, restive vassals who controlled fertile, strategically located territory on Egypt’s northeastern border. Thanks to his personal scribe, Tjaneni, Thutmose’s triumph that day in 1479 bc is the first battle recorded in reasonably reliable detail. With an eye toward history, Thutmose later had his artisans inscribe his exploits on the walls of Amun-Re’s temple at Karnak.

Disregarding his older, more experienced generals’ advice to take an easier path to Megiddo, Thutmose chose to send his troops single file through a narrow ravine near Aruna. His reasoning was sound, if simple: if his generals had recommended an easier line of march, his enemies would have thought of it as well. Thutmose decided to do the unexpected. The king of Kadesh, watching the more likely paths, ignored the mountainous pass at Aruna. Personally leading his men on the perilous route, Thutmose had his mounted scouts, armed for the first time with composite bows, take out any guards posted by the enemy. The next morning he attacked, dividing his army into three wings and driving the rebel forces into Megiddo. It took a seven-month siege to capture the city proper, but with one dramatic victory, Thutmose had effectively restored Egyptian authority in the region.

Like Thutmose of Egypt, Scipio was still a teenager when he commanded a cavalry troop at the Battle of the Ticinus River in 218 bc. A year later, at age 18, he fought at the Trebbia River, a tributary of the Po, where he was wounded. A year after that, Scipio met the Carthaginians at Cannae. He assumed command of the Roman armies in Spain at the age of 26 and immediately set out to avenge his father’s death by restoring Roman rule on the Iberian Peninsula. At the Battle of New Carthage, in 209 bc, Scipio did just that, storming the city and capturing it in seven hours’ time.

Other great captains began their careers equally early in life. The fabled Carthaginian commander Hannibal accompanied his father, Hamilcar, to Spain at the age of nine and witnessed firsthand his father’s conquest of Spain. He first saw combat at age 18 in command of a cavalry battalion. He was 26 when he assumed command of the Carthaginian armies in Spain. Philip participated in the cavalry battles of the Macedonian tribal wars when he was only 16 and assumed command of the Macedonian army at 23. Sargon’s military training began as a boy and continued until he assumed the throne. Only Caesar Augustus, like his famous uncle, Julius Caesar, never experienced war until he took command of one of Rome’s mercenary armies in the Roman civil wars.

Education and Intellect

The great captains were all well-educated men, formally trained by the educational establishments of their times. Sargon II was perhaps the best educated, a classical scholar who was fluent in the ancient Sumerian languages and a military historian who wrote commentaries on his country’s ancient battles. Thutmose III, educated as a priest of Amun-Re, was a botanist and an architect. Scipio and Augustus received solid educations at the hands of private Greek tutors. Hannibal, too, was educated by Greek tutors in the manner of the Hellenic nobles of his day and spoke Punic, Latin, and Greek. Philip II of Macedon received his education in the Royal Page School, the Macedonian West Point, a four-year military academy for the sons of Macedonian nobility run by Greek teachers and experienced combat officers. Philip spoke several languages and surrounded himself with artists and philosophers. He recruited his boyhood friend, the philosopher Aristotle, to instruct Alexander.

Formal intellectual training provides a commander with the confidence to trust his intellect to explain the world around him. Educated leaders think in terms of cause and effect, of chains of action, and influence, where one can bring about desired ends by setting in motion events far removed from those ends. Leaders educated in such a manner are less likely to accept the world as it is or permit tradition and cultural practices to control their actions. Instead, they see themselves as controlling their own fate, able to change the course of events rather than being controlled by them. It is difficult to see how anyone could become a great leader without this psychological disposition. If the great commanders of the past excelled at anything, it was their ability not to become victims of unanticipated change.

The Creativity of an Open Mind

To adjust to changing circumstances requires a mind receptive to new ideas and open to new possibilities. Thutmose III’s adoption of new military technologies, Philip’s invention of new infantry formations and weapons and new tactical cavalry doctrines, Scipio’s redesign and employment of the infantry cohort, and Sargon’s new strategic doctrine of preemptive war are examples of leaders willing to entertain and apply new possibilities. Philip’s new cavalry tactics, training, and logistical innovations made sense because he had already decided to subdue Greece.

An open and receptive intellect permits a leader to challenge existing assumptions about his environment and generate new ways of thinking as a means of adjusting to a new environment. This is an intellectual achievement of the first order and characterizes the thinking of history’s great commanders. Augustus was able to see a new future for Rome only after he had conceived of the Roman world in a completely new way, as a peaceful and prosperous empire based on the integration of conquered peoples into a social order very much different than the old Republic.

Hannibal, too, saw his military campaign against Rome as the vehicle for creating a new world order in which states of relatively equal military and economic power coexisted in relative harmony. Scipio reached for the same vision after Carthage’s defeat and set Rome on the road to empire. Philip’s ability to dream of a unified Greece under the benign tutelage of Macedonia created a world that no Greek had ever before conceived. Thutmose brought about a fundamental shift in Egyptian thinking when he forced Egypt to turn away from 3,000 years of isolation and brave the new world beyond the Nile. And Sargon of Assyria changed the impetus of 200 years of previous wars of conquest, redirecting Assyria’s energies to consolidating its empire and focusing on its domestic requirements. In the sense that the great commanders changed the fundamental paradigms of their age, they created new futures. Some of these futures, like Rome and Egypt, lasted for hundreds of years after the men who had brought them into being were dead.

The great commanders were highly imaginative in a pragmatic sense. Philip II completely reinvented the Macedonian army in order to deal with a set of circumstances—the conquest of Greece—that did not yet exist. In the process, he gave Greece a completely new type of army, one that the Greeks themselves could never have conceived by themselves. In his complete redesign of the Roman army, Augustus gave it a new social form that had never existed in Roman history—a professional army to replace the citizen militia. His invention of new constitutional and governmental forms to govern an empire whose shape and scope had not yet been fully determined ranks among the most imaginative achievements in Western history. Thutmose fashioned new military and diplomatic instruments to deal with the new world confronting Egypt because he could imagine how that new world would operate. The great commanders succeeded because they possessed the imagination to see the world not as it was, but as it could be.

These traits—conceptual thinking from cause to effect, receptivity to new ideas, thinking beyond existing paradigms, and practical imagination—are all intellectual achievements that transcend technology and culture. Taken together, they constitute what might be called imaginative reasoning, where all relevant aspects of problem solving come together to make sense of the world outside the mind. To substitute formulas or technologies for imaginative thought as guides to action is to court disaster on the battlefield and in the world of power politics. The Roman armies that fought Hannibal, for example, were defeated repeatedly because their commanders employed them as they were designed to be employed, while Hannibal fought in a completely different way. The Egyptian army, too, met its death in the wars against the Hyksos for the same reasons, by employing an existing successful military system in radically changed circumstances.

The Self-Confidence of Great Commanders

While certain traits of intellect are important to the success of history’s great commanders, a word of caution is in order. Intellect, per se, is not sufficient for military greatness. Whatever else the great captains of antiquity were, they were first and foremost men of action. It is one thing to conceive of great things, quite another to attempt them and succeed. To attempt great things requires personality traits more related to character and will than to intellect. The ability to trust one’s thoughts, experiences, and judgment is central to the strength of personality required to put sound thinking into action. It is no accident that the great commanders all possessed self-confidence and strong wills.

With the exception of Augustus, who experienced anxiety under stress, the great captains were men possessed of incredible self-confidence. Tradition and religious belief determined most human behavior in ancient societies. Innovation was very difficult to achieve due to cultural inertia. New ideas and actions required not only clear thinking, but a great deal of confidence to make them happen. Consider, for example, the almost extreme degree of self-confidence that Thutmose III possessed when, on the approach to Megiddo, he overruled the advice of his senior military staff and chose the most dangerous path to the battlefield. Or take Hannibal, who conceived of a completely new strategy to war against the Romans. One can only imagine the opposition from his senior generals to his plan to move overland across the Alps and attack Italy from the north. Or Scipio, who was denied sufficient numbers for political reasons to mount a major invasion of Carthage, but did so anyway, calculating that his sudden presence on the African mainland would require Carthage to recall Hannibal from Italy.

The roots of a commander’s self-confidence do not lie in formal education. They rest ultimately in the psychology of his personality. The sources of a leader’s self-confidence are difficult to determine. It seems probable, however, that the roots of self-confidence lie in the strength of personality shaped by experience and practice. With the exception of Augustus, who often seemed to lack the self-confidence so necessary to success, all the great commanders underwent military training and combat at an early age, an experience that taught them to rely on themselves, to endure in difficult circumstances, and to cope with uncertainty. The goal of military training is not primarily to inculcate military skills as much as to shape the psychology of the soldier so that he comes to trust his own abilities in an uncertain environment.

Gamblers on the Battlefield

All the great captains were risk takers, but it was the risk taking of the professional gambler, not the enthusiastic amateur. The battlefield is among the most uncertain places in human experience, a world that can never be completely known or turned to one’s will. There is always uncertainty to be confronted. The great commander confronts uncertainty with the willingness to take risks to reduce the threat of the unknown by plunging into it. Prussian military theorist Helmuth von Moltke remarked that no plan of battle was so complete that it could survive more than a few hours of contact with the enemy. American general Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander in chief of the massive and complex Allied invasion at D-Day, noted that it was the planning, not the plan, that mattered most. Faced with terrible weather forecasts, Eisenhower was able to remain intellectually flexible and take an educated risk to go ahead with the invasion during a short window of opportunity on June 6, 1944. Even then, Eisenhower was doubtful enough of victory to compose two messages to be released to the anxiously waiting peoples of western Europe and the United States—one reporting success, the other manfully accepting full responsibility for the invasion’s failure. Fortunately for the entire free world, Eisenhower was able ultimately to release the first message.

Hannibal and Scipio were also great gamblers. Hannibal’s movement over the Alps marked his propensity to take risks on a grand scale. At Trasimene, he relied on the fog to hide his troops when a sudden gust of wind would have revealed them to the Romans. At Cannae, he exposed his center to draw the Romans into a trap. Had his cavalry not returned in time, he would have faced disaster. Instead, he recorded one of the most overwhelming victories in military history. Scipio’s swift march against New Carthage depended entirely on assuming correctly that the enemy could not react in time to engage him. Scipio’s African campaign, undertaken below strength and without adequate supplies, remains a classic study in military risk taking, as does Thutmose III’s willingness to risk his entire army by moving down a narrow mountain trail to achieve tactical surprise at Megiddo. Without the ability, as Rudyard Kipling says, “to make a heap of all one’s winnings and risk it all on one turn of pitch and toss,” the great captain cannot master the uncertainties of the battlefield. There is always danger in taking risks, but, as the great commander understands instinctively, the greater danger lies in doing nothing.

A Powerful Physical Presence on the Battlefield

Beyond their intellectual and character traits, all the great leaders possessed some element of physical presence that made others love, respect, or fear them. Augustus was possessed of “lightning in his eyes” that made people uneasy in his presence. Scipio demonstrated an air of quiet calm and dignity that gave his soldiers confidence. Hannibal’s physique and demeanor were those of the combat-hardened soldier, fearless and competent in the face of danger. Philip of Macedon, his large head sitting atop a body crippled and scarred from battle wounds, seemed every bit the warrior chief. Thutmose was tall and robustly built, with a large hawk-beaked nose. His troops thought him a god.

Sargon II was not a god, but he wrote a letter to one after his successful campaign against the Urartu in 714 bc. That letter, to the god Ashur, described Sargon’s triumph over heavy odds and harsh terrain. The countryside was so rough in places that the Assyrians had to dismantle their two-wheeled war chariots and carry them by hand (with Sargon still in his chariot). Equipping his sappers with strong copper picks, Sargon was able to cross and re-cross “mountains innumerable.” After reaching Lake Urmia, on the Caspian side of the Caucasus Mountains, Sargon led his men on forced marches against a Urartian army sheltered in a steep valley east of the lake. The Assyrians literally descended from the clouds, falling on the surprised enemy through snow-covered passes and forcing the Urartian king, Rusas, to flee the battlefield mounted on a mare, a retreat so ignominious that Rusas later committed suicide. Sargon’s men seized so much loot that it took the king 50 columns to itemize it in his letter to the god Ashur—a staggering 334,000 gold and silver objects in all.

The physical presence of these commanders was further enhanced by their willingness to suffer alongside their men the same hardships and dangers of battle. Sargon died leading an attack, Thutmose personally led the attack at Megiddo, Hannibal always fought in the middle of the line, and Philip was wounded in battle no fewer than five times. Great leaders share the dangers of their troops and take pains to be seen doing so by their men. Whatever personal charisma was required to convince troops to follow them into the crucible of combat and risk their lives in the physical and psychological horrors of battle, all the great captains possessed it. It remains a maxim of military life that a leader cannot manage his men—soldiers must be led. They follow a great commander for the most basic of reasons: because they respect and trust him and believe that he values them as well and will not squander their lives needlessly.

Assyrian, (8th century BC)

Great Commanders With Great Challenges

Great captains arise when there are great challenges to be dealt with, or when social turmoil loosens the constraints that guide the exercise of power in normal times. Without great challenges, leadership is confined to a narrower scope of events and concerns. Mere competence passes for leadership. In such circumstances, great captains remain only potentially so, carrying out their normal duties, their abilities permitted by circumstance to rise only to the level of competence. Ancient societies were usually remarkably stable over long periods, with the predictable consequence that great captains were nowhere to be found. The inherent conservatism of ancient societies restricted the exercise of power to the usual traditional mechanisms.

The Decline of Greatness on the Modern Battlefield

The secular, democratic, technologically advanced, free-market-economy-based, postindustrial societies that characterize the modern West restrict the opportunities for greatness to a large degree because of their inherent structural limitation on power of all types. The fundamental premise of democracy requires the limited exercise of all power. Generals rarely become political leaders, and political leaders never take on the role of field commanders. One of the fundamental characteristics of the great captains of the past—the fusion of military and political power— is institutionally absent in the modern world. Among the revolutionary leaders of the nondemocratic states of the early 20th century—Lenin, Stalin, Mao, and Hitler—only Mao had ever been a field general and not a very good one at that. The required skill sets for generals and rulers are radically different. One requires attention to detail, the other thrives on attention—period.

The advent of high-tech warfare has further reduced the degree of greatness associated with military achievement. Wars are now increasingly fought by rival systems in which high-level military commanders are virtually interchangeable, and they are won through advanced planning executed with almost complete predictability. General “Stormin’” Norman Schwarzkopf, the American commander during the 1991 Gulf War, could easily have been replaced by any number of other generals who could have just as successfully executed the agreed-upon war plan. Simply put, there is far less room for military brilliance, innovation, and daring in modern warfare. The need for the human dimension in fighting it, at least at the highest command level, has been reduced almost to zero, although there will never come a time when “boots on the ground” are not needed to physically occupy conquered territory.

The day-to-day political control over military operations required by democracies seeking to execute military policy within the constraints of fragile public support and the transparency of events made possible by instantaneous communications technology have further reduced the chances for military greatness. And since democratic political leaders are prevented from being field generals, the next best thing is to make certain that one’s field generals remain sensitive to the requirements of the leadership’s political survival. The congruence of military and political power characteristic in the ancient world is almost impossible in the modern one.

Although all the great captains believed that their nations and empires would last forever, history enforced a much different lesson. It is not difficult to imagine Thutmose III surveying the Nile from his palace at Memphis and thinking that Egypt would always be a great power. Had Egypt not existed for almost 4,000 years before Thutmose was born? By the time Sargon came to the throne, Assyria had been a nation for 500 years, and the empire was already more than two centuries old. Augustus thought of Rome as eternal. All these states and empires came to an end, however, often amid the very circumstances that might have been prevented had other great captains arisen to deal with the tumultuous challenges that eventually consumed them

No doubt great military leaders will arise in the future. And when they do, it is a virtual certainty that their achievements will be marked by the same passion, sense of adventure, and personal experience that marked their emergence in the past. Perhaps the most basic lesson to be taken from the study the great captains of antiquity is the knowledge that the great captains yet to come will be both as remarkable and as recognizably human as those who came before. Circumstances change, but human nature remains the same. Great leaders, at heart, are still men and women—however much their people may hope in darkest times that they are divine.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments